The State Management of Guest Workers

The Decline of the Bracero Program, the Rise of Temporary Worker Visas

In 1943, with the United States fully engaged in World War II, the demand for labor, particularly agricultural labor, was most acute. The full range of options were explored—employing Japanese-American internees, prisoners of war, US soldiers, conscientious objectors, women (Women’s Land Army), and nonfarm youth (Victory Farm Volunteers).1 On the East Coast, farm workers from the Bahamas2 were recruited for their past agricultural experience in Florida, their English-speaking skills, and pliability. As a grower explains why pliability mattered to him in a proposed temporary work contract he submitted to the US Department of Agriculture: “The vast difference between the Bahama Island labor and the domestic, including Puerto Rican, is that the labor transported from the Bahama Islands can be deported and sent home, if it does not work, which cannot be done in the instance of labor from domestic United States or Puerto Rico.”3

When twentieth-century historians analyze the state’s role in managing labor migration, most often the discussion is about the large-scale, US-Mexico Bracero Program, a wartime labor relief measure that began in 1942 but was continued until 1964 at the behest of US agribusiness interests.4 Less recognized is that in 1952, the US government created a small program for temporary work visas, known as H-2 visas, which allowed agricultural firms on the East Coast to recruit temporary laborers from the Caribbean, particularly the British West Indies. This chapter explains the reasons for the fall of the Bracero Program and the subsequent, concomitant rise of temporary visa “H-2” programs. The program was extended and expanded in the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act and broadened dramatically beyond agriculture in the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act to include H-2A temporary agricultural workers, H-1B specialty occupations, and H-2B seasonal and unskilled nonagricultural workers. Regardless of the persistent political clamoring for another Bracero Program, US immigration policy has consistently maintained temporary work visas over the past seventy-five years to meet the needs of US place-bound industries that in the twenty-first century bring Indian and Chinese software developers to Silicon Valley, Mexican hotel maids to Vail, and Mexican tobacco pickers to North Carolina.

Antecedents of the H-2 Program

The story of migrant labor on the East Coast of the United States begins and ends in the sugarcane fields of Florida. Sugar was originally a slave crop. First cultivated in Asia, the Portuguese and Spanish crowns oversaw the production of sugarcane in Brazil and the West Indies, especially the Caribbean colonial outposts of the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. Britain also brought sugar cane to its tropical and subtropical colonies, as well as the slaves to cultivate the crop, and the food became the staple of caloric intake for all classes of British society.5 Cane labor had been racialized since its colonial origins, from chattel slavery times through the 1990s, with Blacks and Chinese providing most of the labor.

Harvesting sugarcane was—and continues to be—among the dirtiest, most hazardous, and most difficult jobs. Workers used machetes to cut the cane stalk; over time, metal guards for hands, feet and shins were developed to minimize the number of workplace accidents that resulted in contusions and loss of digits and limbs. To facilitate the harvest, growers burned the crops to reduce excess leaves and stalk. In Florida, the controlled burns forced out wildlife (such as rats, cougars, alligators, and venomous snakes) from the fields, endangering workers. Prior to the implementation of safety equipment, the frequent loss of limbs, cuts, burns, and other workplace injuries made sugarcane cultivation one of the most dangerous occupations in the United States. After the abolition of slavery forced growers to enlist paid workers, they depressed wages to the level of debt peonage. The wages, substandard housing, company store arrangements, and other forms of social control were always major sources of contention. These industry practices were called into question during the 1942 season.

Charges were filed by the Department of Justice on November 6, indicting the US Sugar Corporation and four of its supervisors of peonage.6 Newspaper articles during the season characterized labor relations in Florida’s sugar firms in terms of peonage and slavery.7 A federal warrant was eventually issued for US Sugar’s personnel manager and supervisors M. E. Von Mach, Evan Ward McLeod, Neal Williamson, and Oliver H. Sheppard on the charge of peonage. Supervisors at five labor camps were charged with various forms of social control: debt bondage in their piece-rate wage structure; substandard housing conditions; lockdowns on plantations; illegal rules to keep labor captive and tied to labor camps; and binding men to their beds so they could not escape. In response to these investigations, Florida sugar growers shifted from African-American labor to Bahamian labor in 1943, which growers hoped would provide a more passive labor force.

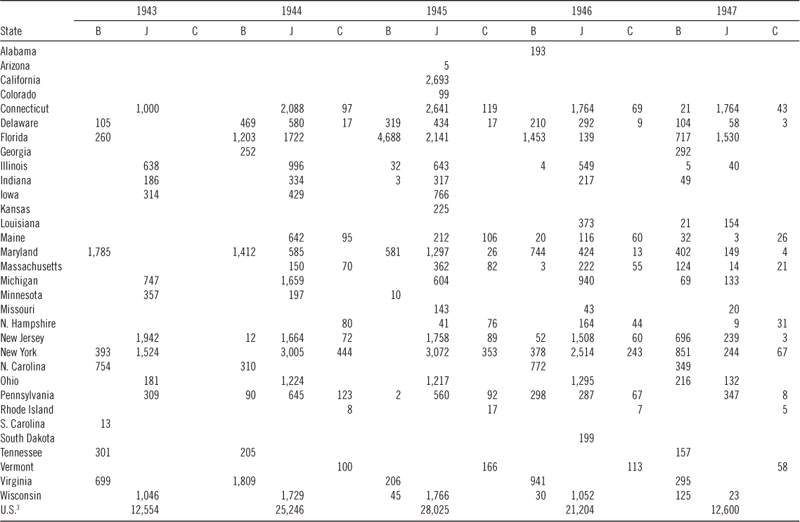

Growers enlisted 4,310 temporary workers from the Bahamas in 1943 to work in the truck crops and fruit crops of eight states initially. This expanded over the next five growing seasons to twenty-five US states. On March 16, 1943, the first contract was signed between the US and British colonial government in the Bahamas, but growers needed more labor, so the US government turned to Jamaica and signed a similar contract on April 2, 1943, resulting in 8,244 laborers distributed across eleven states.8 In 1944, East Coast agricultural interests also turned to Barbados, primarily for agricultural work in Florida, but about three hundred men also traveled to Delaware and Wisconsin in 1946.

The United Fruit Company (UFC), better known for their banana cultivation in Central America, was given the exclusive subcontract to recruit and process all temporary workers from the Caribbean. As a labor contractor, UFC set up processing centers in the major ports of Nassau, Kingston, and Bridgetown. All potential temporary workers presented themselves to UFC officials to secure work authorization in US agriculture. With significant land holdings in the British West Indies, the company leveraged its influence with the US government to handle the recruitment process. The US government, through the Department of Army, proved it was not up to the task of labor recruitment, and UFC was in the right place with the right track record of recruiting international labor to meet US needs.

The SS Shanks, the first of two ships embarking from Kingston to South Florida, transported Jamaican workers at the advent of the 1943 growing season.9 Equipped to hold a maximum of eighteen hundred passengers, a total of four thousand were crammed onto the boat. Very little oversight by either government led to substandard transport conditions. The ensuing unsanitary conditions, lack of food and water, and military police confiscation of their rum, razors, and bay-rum cologne led to worker protests that were eventually assuaged upon landing on US soil. Intergovernmental correspondence suggests the men were treated better upon arrival, but it is not clear if the US government returned some confiscated goods or repaid workers for lost items, or if men simply found landfall better in comparison to their mistreatment on the ships. Initial government involvement did not allay transportation problems.

The Shanks incident was in early May 1943; by early June, another protest arose on the island of Jamaica when the US Army’s estimates of the capacity of a transport ship were reduced from three thousand to twenty-seven hundred workers. The US Army was charged, under authority of the War Labor Board, to determine maximum capacity for transport ships. Those individuals left at the port, “many of whom had sold much of their personal property and had bought supplies for the trip, demanded compensation. … [In response], the American government granted 3 pounds (approximately $12.09) each to 554 of the workers. This was supplemented by an additional grant of 2 pounds each by the Jamaican government and the latter requested reimbursement from the American government.”10 There is no evidence that the United States reimbursed the Jamaican government.

Table 1. US Wartime Labor Relief Programs, 1943-1947,1 by Nation of Origin (Bahamas, Jamaica, Canada)2

1. Numbers are based on one-day figures (a particular day between May and September) and should not be necessarily construed as full-season counts. For instance, Rasmussen (255–56) offers total counts of Jamaicans in 1944 totaling 15,666 Jamaican workers and 17,291 in 1945. These underestimates, compared to the above one-day counts, point to the less-than-perfect accounting of the program.

2. B = Bahamian, J = Jamaican, C = Canadian (Newfoundland)

3. Though not always identified by reception state, Rasmussen notes Barbados sent 909 workers in 1944, none in 1945, 3,087 in 1946, and 2,947 in 1947. “Of these [1946], 75 were employed in Delaware, 2,645 in Florida, and 227 in Wisconsin. . . . [In 1947,] Delaware, 1; Florida, 617; Louisiana, 17; Massachusetts, 2; and New York, 4.” U.S. totals include temporary workers from all four nations.

By 1944, some Jamaicans were rounding out their northern contracts by finding winter work in Florida’s cane fields. The vast majority of the 17,649 workers were contracted to work in Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, but the 1,722 workers tallied in Florida fell well short of labor demands. So, the US Sugar Corporation, the largest and most notorious employer, began to aggressively recruit Jamaicans in the 1945 season; their recruitment program, however, did not entice Jamaicans as anticipated. For example, the first group of 1,523 men traveled on April 1 from Kingston to Port Everglades. But a second shipment carrying only 838 men left on April 11. Even though 1,634 men departed from Kingston on that day, only half were willing to work for US Sugar.11 When the workers protested the unsatisfactory living conditions and proved troublesome to their employers, the US government allowed Big Sugar to turn to Barbados to recruit workers in 1946. Based on the agreement originally signed between the US and Jamaican governments on July 24, 1944, the US-Barbados agreement was essentially the same, with the exception that a $5 advance given to Jamaican workers upon entry into the United States was not extended to those from Barbados.

One key protection that the Jamaican government secured during the war years, with very little US War Food Administration resistance, was to protect its citizens by barring recruitment to the Deep South. Internal correspondence within the War Food Administration identified a range of concerns, from Jamaicans having different customs and social patterns than African Americans, to the absence of racial segregation and Jim Crow laws in Jamaica, and African American acquiescence to Jim Crow power differentials that officials feared Jamaicans would not tolerate.12 Conceding that Jim Crow was objectionable to Jamaicans such that they may not serve as ideal (in other words, docile and passive) labor force, the mutual solution was to bar temporary workers south of the Mason-Dixon line.13 In the first years of the arrangement, Jamaicans were by and large not sent to the Deep South states. Florida was the exception—though, as noted above, treatment of workers in the state was highly objectionable from workers’ perspectives.

Canadian workers, primarily from Newfoundland, were recruited to work in the US Northeast beginning in 1942, as the grain harvest relied on workers and machinery freely crossing the border. Yet employing and transporting workers from Newfoundland did not pick up until 1944; such work was most often arranged in the New England and neighboring states. Beyond grain harvesting, Newfoundlanders started picking potatoes in Maine in 1944, and that continued through 1947. The number of Canadian laborers never approached twelve hundred, however: New York was always the largest recipient (444 in 1944, 353 in 1945, 243 in 1946, and 67 in 1947). As soon as the war ended, Newfoundlanders were anxious to return to Canada to make way for returning US veterans. What began as a formalization of a practice decades old, the lending of Canadian labor and machinery over the border was a standard practice of wheat and grain growers, though it never grew in scale to compare to the number of laborers from the Caribbean.

The United States came to Barbados relatively late and sporadically. At the request of the US government, Barbados sent 909 workers in 1944, none in 1945, 3,087 in 1946, and 2,947 in 1947. From 1946 to 1947, most Barbadians in the United States were employed in Florida (3,262), with fewer than one hundred working in Delaware, Louisiana, Massachusetts, New York, and Wisconsin. The focus on Barbados was specifically meeting the demands of US Sugar and to a lesser extent their competitors in Florida. As much as the United States viewed temporary-labor relations as one-sided or at the very least bilateral, both Great Britain and their Caribbean colonies sought more negotiating power. The British West Indies Central Labor Organization (BWICLO) was formed in 1944 to regulate the overseas flow of laborers from British colonial holdings in the Caribbean. A product of finding themselves caught between US and British influence, the coalition was voluntary, with no executive authority; British historian Ashley Jackson contends that it was a product of the Anglo-American Caribbean Commission of 1942 that sought more cooperation among the English-speaking nations and British colonies of the Caribbean, particularly influenced by US interests.14 Forming the BWICLO was symbolic of the larger British response to coalesce their holdings into a federation. All the pieces were in place when, in 1952, the US Congress reauthorized the Immigration and Nationality Act.

The H-2 Program of 1952

These wartime measures, though clearly small in scale, provided the basis for the enactment of the H-2 temporary visa program in the 1952 McCarran-Walter Immigration and Nationality Act. These measures were continued because growers along the East Coast migrant stream received the type of labor they so desired (pliable, cheap, temporary, and controllable), the colonial governments of the West Indies had a reliable source of addressing chronic unemployment and underdeveloped economies (labor migration and remittances),15 and the US government met the demands of agribusiness without relying on undocumented immigrant labor. The full text of 1952 INA Section 101 created what became known as the H-2 program:

(H) an alien having a residence in a foreign country which he has no intention of abandoning (i) who is of distinguished merit and ability and who is coming temporarily to the United States to perform temporary services of an exceptional nature requiring such merit and ability; or (ii) who is coming temporarily to the United States to perform other temporary services or labor, if unemployed persons capable of performing such service or labor cannot be found in this country; or (iii) who is coming temporarily to the United States as an industrial trainee.16

Temporary labor was codified into immigration law if individuals had desired skills or merit in short supply (H-1), were qualified and selected as industrial trainees (H-3), or provided “unskilled” labor when not competing with unemployed US citizens (H-2). In practice, the second article was narrowed to exclusively agricultural labor to accommodate the needs of employers on the East Coast who did not have ready and full access to the Mexican braceros.

The US government facilitated this relationship by creating a temporary-visa contract between the government and grower on a per-worker basis. Growers gained several advantages: contracts could be negotiated in their favor, they could pre-select their workforce, and they could use deportation as a means of control in the fields.17 Individual work contracts tied the visa holders to a specific employer; protests, work stoppages, or the failure to achieve a certain harvest quota could result in deportation and subsequent blacklisting.

The Rise and Demise of the Bracero Program

As details of the H class visas were hammered out in Congress and officially recorded as law on June 29, 1952, the US Department of Agriculture was putting into practice Public Law 78 that Congress passed on July 12, 1951.18 The focus of that law was to formalize US-Mexico labor relations in the western half of the United States with another temporary worker program operated on a mass scale to meet the needs of large-scale agribusiness. The Bracero Program facilitated large-scale temporary farm worker recruitment from Mexico, but most operations that utilized the program were west of the Mississippi River (in particular California and Texas by this time). For the few bracero destinations in the southern United States (Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and North Carolina), the Mexican influx was on a much smaller scale (see table 2). Between 1942–1947, 410 braceros were employed in North Carolina. Arkansas was an exception, due to its need for a mass temporary labor source as cotton growers in the state prepared to mechanize their operations. No braceros were enumerated in the twenty-two-year history in the states of the Northeast.

Table 2. US States Employing Braceros, 1952

| Workers Contracted | Workers Recontracted | Workers Employed on 12/31/52 | |

| Arkansas | 25,658 | 2,705 | 500 |

| Georgia | 387 | 209 | 0 |

| Louisiana | 739 | 83 | 17 |

| Mississippi | 60 | 0 | 0 |

| Tennessee | 264 | 142 | 0 |

| South Region | 27,108 | 3,139 | 517 |

“Workers contracted” refers to those newly hired and given a contract, no prior contract being involved. “Workers recontracted” refers to those whose valid but expiring contracts were renewed.” Richard Martin Lyon, “The Legal Status of American and Mexican Migratory Farm Labor,” PhD diss., Cornell University, 1954, 225.

From 1942 to 1947, North Carolina growers employed 410 braceros and in effect initiated the first migrant stream from Mexico to the rural South. The author interviewed Don Liberio, a former bracero, who recounted his experiences working in North Carolina in 1947.

In North Carolina, we were picking green beans. We also picked potatoes. But there were too many men in the fields, and thus not enough work. In potatoes and green beans, we earned forty cents per bushel, or about eight dollars per week, after deductions. After the contract ended, we had to pay transportation home. In North Carolina, we often complained and stopped work because of the rotten food. There was a man, he was protesting and complaining about the food. The next day he was gone, nobody told us what happened to him and we didn’t ask. Later we heard that they killed him.19

Many stories abounded of braceros who were killed to collect the insurance money or to punish recalcitrant agitators.20 Quite likely, it was the message itself that mattered, as growers could use fear to keep workers in line with the message that “if you strike, you take your life into your own hands.” Don Liberio recalled several contract violations by potato and green bean farmers. He reported that the food served in the camp was occasionally rancid. If the workers united to complain, the quality of food would temporarily improve, only to return to spoiled servings. Yet the program was never designed to meet the needs of growers in the East Coast migrant stream.

The Bracero Program began on August 4, 1942, in Stockton, California, as a result of the US government’s response to requests by southwestern agricultural growers for the recruitment of foreign labor. The agreement, negotiated between the federal governments of Mexico and the United States, stated the following general provisions that would come to define the program’s twenty-two-year existence.21 The first provision barred racial discrimination targeted at braceros: “The Mexicans entering the US under provisions of the agreement would not be subjected to discriminatory acts.” The second provision guaranteed that US growers would shoulder the costs of migration and temporary settlement: “Workers would be guaranteed transportation, living expenses, and repatriation along the lines established under Article 29 of Mexican labor laws.” The third provision concerned the displacement of US workers to guarantee that braceros would not undercut native wages or be used as strikebreakers: “Mexicans entering under the agreement would not be employed either to displace domestic workers or to reduce their wages.”22 Under many of the same agreement guidelines, though utilizing different administrative channels, nine months later the railroad industry secured the importation of Mexican laborers to meet wartime shortages.23

The first provision was designed explicitly to ban discrimination against Mexican nationals and served as the key bargaining chip by the Mexican government to promote safeguards of braceros’ treatment by Anglo growers. The arrangements of the First Bracero Program, during World War I, were conducted without the input of the Mexican government.24 As a result, Mexican nationals worked in the United States without protections and, subsequently, workers were subject to a number of discriminatory acts. The protections from discriminatory treatment stemmed from Executive Order 8802, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 25, 1941, which stated that, “there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin, and … it is the duty of employers and of labor organizations, in furtherance of said policy and of this order, to provide for the full and equitable participation of all workers in defense industries, without discrimination because of race, creed, color, or national origin.” In relation to E.O. 8802, the Bracero Program was couched as a government-sponsored program in the larger service of national defense, and it recognized the reality that Mexicans were subject to discrimination, whether on the basis of race, color, and/or national origin.

From 1942 to 1947, no braceros were sent to Texas because of the documented mistreatment of Mexican workers by Texas growers and other citizens. A series of assurances by the Texas state government were secured before growers were allowed to import labor from Mexico. Texas was infamous for the Jim Crow–style segregation and racial violence practices that defined the Postbellum South, and the state was responsible for more lynchings of Mexicans than any other state. Until the 1950s, the Mexican government also blacklisted Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Montana, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Wyoming for discriminatory practices documented in each of the states. The source of contention was a prevalent practice in the sugar-beet industry that paid Mexican workers considerably less than Anglo workers for the same work. The discriminatory wage structure illustrated a second-class citizenship that Mexican laborers were subjected to throughout the Midwest and Rocky Mountain states. An interview with the tortilla vendor who provided food for braceros in the San Luis Valley of Southern Colorado notes not only the racial discrimination that braceros faced from Anglos but also the complex relations among Anglos, Mexican Americans, and braceros in the Valley.

SEÑOR PALMAS: There was a certain amount of animosity between the seasonal workers and the Hispanic population here and it’s basically just a cultural difference in terms of how they view their Hispanic-ness if you want to put it that way. … So those guys are … a lot of people here are a bunch of upstarts, blabbermouths, push. … They view us as backward, don’t even know the language. On and on and on. … And of course those people who are Anglo certainly view them as Chicanos and cholos and a little bit of … intrinsic fear of an outsider. … See what I’m saying? So there’s all kinds of degrees there, all kinds of attitudes. There was absolutely no acceptance either from the braceros or the guys that come in. To the Hispanics here they were all wetbacks. Not even braceros. They were just wetbacks.25

The provision protected braceros, in theory, from racial discrimination, as Colorado was one blacklisted state due to the sugar-beet industry’s discriminatory wage structure (in northeastern Colorado, not the San Luis Valley) but once the ban was lifted, no laws were designed to protect braceros from the discrimination they faced by Mexican Americans who often sought to distinguish themselves from immigrants or what many Anglos saw as all “wetbacks.”

The second provision was designed to guarantee workers safe passage to and from the United States as well as decent living conditions while working in the United States. The costs associated with transportation, room, and board would be covered by someone other than the workers if the article was followed to its exact wording. But these costs were subject to negotiation by the Mexican government; as a result, workers had a number of these expenses deducted from their paychecks. Individual work contracts signed by braceros and representatives of both the Mexican and US governments set standards on how much could be deducted for room and board.

Different groups shouldered transportation costs, depending on which time and place the braceros were migrating to and from. Braceros did not pay transportation costs from the recruitment centers in Mexico to the US processing centers and eventual job sites. As Don Francisco noted on his return trips from the US fields: “And from here to there when we went home they paid for our trip to Empalme too. When we were about to leave they bought our ticket so we could go back.”26 But they absorbed the costs associated with getting to the Mexican cities where braceros were recruited, which varied depending on where the recruitment centers were located. Don Andres recalled the best-case scenario when asked if he paid to get from his home to the Mexico recruitment center: “No, because they gave us an official government letter. With that letter we came. There were some that they did charge. But that time they gave us a letter.”27

Throughout the duration of the program, the US and Mexican governments struggled over where recruitment centers would be located because the United States was responsible for paying the transportation costs. The US government wanted recruitment centers near the US-Mexican border to reduce costs, whereas the Mexican government wanted recruitment centers in the interior of Mexico where the major sending states were located. These struggles had major consequences for the braceros, who had to secure the funds to pay their way to the recruitment centers.

The final provision was designed to reduce competition between domestic and contracted labor, and the United States government played two roles in assuring that competition would not arise. The first role was the determination of the “prevailing wage” in each region of the country. To ensure that braceros were receiving the same wage as domestics, the prevailing wage was determined prior to the harvest season in each locale, and braceros were to receive that wage. The prevailing wage was approved by the Department of Labor, but it was in fact growers who collectively determined the “prevailing wage” they were willing to pay.28 Braceros often found themselves trying to earn wages at a piece rate (based on how much they could pick by weight) while relegated to the sections and rows of fields where the plants’ yields were the lowest. Don Antoñio recalled working in cotton fields where braceros picked from plants that were only knee high, whereas domestic farm workers picked from the taller plants with the best yields.

DON ANTOÑIO: And then they put us in really bad parts sometimes. Parts where it [the cotton] was really small. And those that were from here they put where it was better.

INTERVIEWER: So there still were local people working?

DON ANTOÑIO: Yes, there were local people. Of those that were from here. Of those who got the best job.29

It was also the responsibility of the Department of Labor to designate when a certain region had a labor shortage of available domestic workers. Again, growers were the key to this determination because they were responsible for notifying the department when they expected labor shortages to occur. Most often, growers would set a prevailing wage rate so low as to effectively discourage domestics by requiring them to work at wage levels below the cost of living in the United States. The lack of enforcement by state, federal, and consular agencies often defined the modus operandi of how the Bracero Program was experienced on the ground.

In terms of each provision, the Bracero Program was lived out much differently by the workers than how the program was designed to work on paper. Though intended as a wartime labor-relief measure, the Bracero Program was continually reauthorized until 1964. At a time when the United Farm Workers began to ascend, one of their main targets was the Bracero Program. Ernesto Galarza’s Strangers in Our Fields (1956) and Merchants of Labor (1964) were indictments of how the Bracero Program operated, and the nascent Chicano movement brought Mexican Americans together partially by casting braceros as undesirables and unwelcome competitors in the fields. An advertisement titled “Rotten Deals in Tomatoes: Government Gives Away Our Jobs” in the United Farm Workers trade journal El Malcriado employed strong language as to how the growers treated bracero workers:

The Bracero Program was ENDED by Congress two years ago. … The growers pay lousy wages, refuse to sign a contract, and turn local workers away. THEN they scream for braceros. They know they can pay braceros less, since $1 in US money equals $12 in Mexican money. The Bracero Program is just one more weapon which the growers use to beat us down and keep us poor.30

The ad goes on to explain that the Teamsters—the competing labor union for farm-workers—supports a temporary-worker program because of its sweetheart deals with growers.

Clearly, the UFW did not consider braceros as “workers”—or at the very least not “our workers”; they are characterized in the ad as simply a weapon in the growers’ arsenal. The organized labor divide between Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants, as Chicano historian David Gutierrez aptly notes, highlights that common ancestry is a tenuous link when labor, border, citizenship, and assimilation pressures are all operating.31

Economist Philip Martin identifies other factors that led to the demise of the Bracero Program, claiming it was President Kennedy watching Edward R. Murrow’s farmworker expose Harvest of Shame that ended the program, while sociologist Kitty Calavita claims the demise was due to bureaucratic battles within the US state that made the program untenable with regard to controlling the illegal immigration problem (basically, the Department of Justice and Immigration and Naturalization Service determined illegal immigration to be a bigger issue than the USDA claim of agricultural labor shortages).32

Whereas the Bracero Program expanded dramatically after World War II, the sheer scale of the operations raised concerns by farmworker advocacy organizations, local communities, and small farmers. The United Farm Workers called braceros “scabs,” “strike-breakers,” and a tool that growers used against Mexican-American farm workers in their struggle for better wages, humane working conditions, and collective-bargaining rights. The mass-deportation campaigns of Operation Wetback in 1954 pointed to the precarious status of braceros and undocumented workers. The exigencies of labor demand could quickly turn to repulsion, repatriation, and deportation when the political winds shifted. The Bracero Program officially ended in 1964, but by no means did that portend an end to temporary-worker programs.

“I Am an H-2 Worker”

The Hart-Celler Act of 1965 was a landmark shift in immigration policy, but all revisions of the INA were in section 201 of the law to end discriminatory national quotas and establish family reunification as the basis for naturalization. The law included the exact provision for temporary visas found in the 1952 Act. Administratively, the H-2 program solidified the relationship between the BWICLO and US Department of Labor to create primarily a sugar plantation labor force, always one step away from slavery and indentured servitude, to serve as the labor safety valve for the East Coast migrant stream. When labor demands increased, the valves were opened to expand the H-2 program; when they decreased, the valve could be shut off. As DeWind, Seidl, and Shenk note, the H-2 program issued more than ten thousand visas per year through the 1960s and 1970s, with the vast majority (about 80 percent) going to the sugarcane firms of Florida.33 The recruitment process was streamlined to locate men, most often from Jamaica, who were physically able to perform stoop labor, proficient in English and sufficiently intelligent, and possessing the ideal temperament to take orders, observe the law, and avoid behavior that would result in blacklisting. One recruiter described the process:

We’ll run through 800 men a day. … Three tables are set up representing three stages of processing. At the first table, we simply look at a man as a physical specimen and try to eliminate those with obvious physical defects. At the second table, we’re trying to test intelligence and see if the man can understand English as we speak it by asking simple questions. The third table is where we attempt to find out about the man’s work background. We also check our black book to see if a man has been breached (i.e., sent home for violating the contract). … The final stage of pre-selection is the check by the Jamaican authorities of police records.34

Reports from the BWICLO noted that in the mid-1960s, “West Indian workers struck in protest over low task rates on the average of once a month. … Fifteen men were sent home for agitating and inciting others to strike … The men returned to work the following day after five men were removed. … Since repatriation of one worker who was deemed the ring leader, work has progressed smoothly.”35 According to Rob Williams of Florida Rural Legal Aid, the wage structure was challenged as early as 1968 and the labor dispute resulted in the deportation of H-2 workers.36 This created a vicious cycle: growers responded to worker protests with blacklists and deportations, and the Florida Rural Legal Aid filed lawsuits on behalf of H-2 workers to secure the wages promised. It was not until September 11, 1992, that a labor peace accord was struck.37 US Sugar finally succumbed to all other competitor practices and mechanized one year after the accord; as the H-2A program began to take off, the company—the last holdout to the upfront costs of machinery in the industry that created the program in the first place—was officially out of the business of employing temporary visa workers by 1993.

One way workers were systematically cheated out of wages was the development of a task rate system that took piece rates to a new level of exploitation. The task rate was designed to recognize that not all sugar cane rows are created equal, so a wage system was created to pay by the row, with the price determined on the difficulty of tasks by row. Similar to the low-yield cotton rows that ex-bracero Don Antoñio experienced, many H-2 workers found themselves picking from sugarcane rows with relatively lower yields. Stalks that needed additional clearing, grew unevenly, or posed other complications meant workers were paid a premium in theory—but in reality, it often meant the wages were driven down on the comparatively easiest rows.

Piece rates were employed because they maximized the chances for self-exploitation as workers were led to believe that the harder and faster they worked, the more they would earn. From the company perspective, the ever-shifting piece rate allowed them to maximize profits by securing more labor at lower pay scales. Industry practices often blurred the line between low wages and debt peonage.

The Long-Term Effects of the H-2 Program

The structure of the temporary visas also compounded the issue, particularly the compulsory savings program. The sugar companies deducted transportation, room, and board costs, but a much larger share of deductions comprised the 25 percent the Jamaican government withdrew as part of a compulsory savings program, even though only 23 percent of this deduction was returned to the men in Jamaica. The 2 percent, and often more, was marked for health insurance, but a congressional investigation found the “deduction generated more than $600,000 over and above the costs of the insurance policy covering the workers, and that the policy’s benefits were so minimal as to be meaningless in the US healthcare system.”38 Jamaican newspapers also reported how Ministry of Labor officials, charged with serving as the workers’ advocates, in their roles as staff of the BWICLO, used the compulsory savings to purchase durable goods in Canada and the United States, only to resell those items and keep both the profits and interest on workers’ accounts.

In 1986 the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) was passed. It not only upheld the temporary visa program but expanded it to several other occupational sectors.39 Under the new H-2A program, growers could still gain access to a steady stream of temporary labor if they were willing to meet the bureaucratic requirements. The H-2A program was reauthorized through IRCA, and temporary visas were also expanded to include H-1B (specialty occupations) and H-2B (wage-shortage industries) temporary migrants as well. Employers were required to provide free and adequate housing, and code inspectors were quite thorough. As a result, H-2A farm labor camps often offered better housing than any previously available to migrants. Growers also had to adhere to an adverse-effect wage rate and ensure that working conditions did not deter domestic interest.

The H-2A visa is a continuation of the Bracero Program for agribusiness but includes administrative controls, certifications, and oversight written into law. H-1B visas were reserved for specialty occupations, particularly in the computer industry. H-2B visas focused on nonagricultural “wage shortage occupations,” including landscaping, hotel cleaning, and seasonal work. For the first time, employers were held accountable for employing undocumented labor, though law enforcement shifted to border defense.

The process has been accelerated and institutionalized by a renewed grower utilization of the H-2A program. Data from 2003 show that agricultural firms in all fifty states employ H-2A labor. In 2002 there were forty-two thousand visas issued, which increased to forty-five thousand in 2003. Tobacco is the largest single crop that employs H-2A workers with tobacco workers constituting 35 percent of all H-2A visas. Tobacco growers are primarily in North Carolina, Kentucky, and Virginia. Mexican workers are the main visa recipients. The Global Workers Justice Alliance estimates 88 percent of H-2A workers are Mexican, according to their analysis of 2006 DOL data (40,283 of 46,432 visa holders) (see table 2).

Based on US Department of Labor data released in FY2014, the H-2A has ballooned to a 116,689-person program utilized by nearly sixty-five hundred US companies in all fifty states. Tobacco cultivators are increasingly relying on H-2A workers, which explains why 12 percent of all workers were contracted in North Carolina. Today, the majority of H-2A workers are employed by the North Carolina Growers Association.40

The vast majority of temporary workers come through the H-1B program, which included 946,293 positions certified in FY2014. Social scientist Rafael Alarcón refers to these specialized workers, primarily computer engineers, financial service employees, and scientists, as cerebreros (brainers) due to their recruitment for mental labor.41 A small but significant contingent of Mexican citizens have entered the United States on H-1B temporary visas, but most are from India, China, and Great Britain. In FY2014, the five largest employers of the H-1B cerebreros were Price-waterhouse Coopers, Cognizant Technology Solutions US Corporation, Deloitte Consulting, Wipro Limited, and Tata Consultancy Services.

The H-2B program is the category left for temporary entry as long as an employer demonstrates no native workers are willing to take the jobs at the prevailing wage. Landscaping, hotel cleaning, forestry, and other seasonal occupations, which traditionally rely on undocumented Mexican labor, make up the majority of the 93,649 positions certified. Department of Labor reports identify that in FY2014 the laborer/landscaper position accounted for 37 percent of all H-2B certified occupations. In 2007 the DOL certified 254,615 positions under the H-2B program. The top six employers of those workers included the Brickman Group, hiring 3,020 landscapers and groundskeepers; Vail Corporation, hiring 1,988 sports instructors, housekeepers, and short-order cooks; Trugreen Landcare, hiring 1,731 landscapers and groundskeepers; Marriott International, hiring 1,696 housekeepers, dining room attendants, and kitchen helpers; Eller & Sons Trees, hiring 1,433 forest workers and tree planters; and Agricultural Establishment Landscapes Unlimited, hiring 1,358 landscapers and groundskeepers.42

The Vail Corporation was one of the largest employers of temporary visa holders under the H-2B Program. Employers of H-2B visa holders are seeking labor defined as non-specialty, seasonal work when sufficient domestic labor sources cannot be located at comparable wage rates. In 2009, Vail was the third largest employer of H-2B workers hired for housekeeping and short-order cooks. Those top three employers were paying 6,392 visa holders on average $8.16 per hour.43 By 2010, federal administrative rule changes and stricter enforcement including more frequent audits resulted in Vail no longer employing H-2B workers. The shift has been to employ J-1 visa holders: Vail relies on third parties (online international student exchanges) to facilitate the flow of foreign labor into Vail (followed closely by Aspen, Park City, Winter Park, and Northeast ski resorts). A truism of temporary-worker programs is once the networks are established, there is no such thing as temporary. Permanent settlement, primarily in the bedroom community of Leadville, is where the Mexican undocumented labor force resides to do the unskilled labor in Vail that began as a H-2B temporary visa program.

Conclusion

With the end of the US-Mexico bracero guest-worker program in 1964 and current political appeals in Washington, DC, for a new temporary-worker program, one would think that the United States did not have temporary-worker programs already in place. But since 1965 the US government has continually provided a mechanism for industries, particularly but not only agriculture, to have access to employ temporary immigrant laborers.

With passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, one provision extended the Bracero Program with the development of an H-2 temporary visa program. The H-2 (after 1986, the H-2A) program served largely as the safety valve for large-scale agribusiness and its seemingly unending desire for cheap, pliable, temporary labor. The H-2 program was severely underutilized because the other, less bureaucratic option, hiring undocumented immigrants, was never deemed illegal or worthy of sanction until the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), which, for the first time in the history of the nation, held employers responsible for knowingly employing undocumented labor.

Long, intractable political debates on immigration at the national level have called for an expansion of temporary-worker programs. The debate is not about whether or not temporary worker programs will be a part of comprehensive immigration reform. Democrats tend to lobby for increasing the number of visas allocated through existing, orderly H-class visa programs. Republicans tend to call for large-scale programs more akin to the Bracero Program with significantly less bureaucratic oversight. Temporary worker programs are certain to be an integral component of US immigration policy well into the future. Yet the plight of farm-workers today is much the same as it was during the H-2 and Bracero Programs.

Notes

1. Oregon State College Extension Service, “Farm Labor News Notes (17),” August 6, 1947, Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections and Archives; Wayne Rasmussen, A History of the Emergency Farm Labor Supply Program, 43–7 Ag. Monograph 13 (Washington DC: US Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Agricultural Economics, 1951): 105–50. Eiichiro Azuma explores the effects of these war-era labor arrangements on Japanese immigrants employed by Japanese-American growers in the 1950s in ch. 8 of this volume.

2. Rasmussen, History, 233.

3. Rasmussen, History, 234.

4. See Rosas (ch. 12 of this volume). In addition, see Deborah Cohen, Braceros: Migrant Citizens and Transnational Subjects in the Postwar United States and Mexico (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011) regarding recent interest in the Bracero Program; see also Gilbert G. Gonzalez, Guestworkers or Colonized Labor? Mexican Labor Migration to the United States (New York: Routledge, 2013); Mireya Loza, Defiant Braceros: How Migrant Workers Fought for Racial, Sexual, and Political Freedom (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016); Don Mitchell, They Saved Our Crops: Labor, Landscape, and the Struggle over Industrial Farming in Bracero-Era California (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012); Ronald L. Mize, The Invisible Workers of the US-Mexico Bracero Program: Obreros Olvidados (Lanham, Md.: Lexington, 2016); Ronald L. Mize and Alicia C.S. Swords, Consuming Mexican Labor: From the Bracero Program to NAFTA (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010); Ana Elizabeth Rosas, Abrazando el Espíritu: Bracero Families Confront the US-Mexico Border (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014). The sheer scale of the Bracero Program rationalizes this focus, with more than 4.5 million work contracts signed and braceros working across thirty US states.

5. Sidney Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (New York: Penguin, 1986).

6. Clarence Maurice Mitchell Jr., The Papers of Clarence Mitchell, Jr., 1942–1943, ed. Denton L. Watson and Elizabeth Miles Nuxoll (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2005), 32; Daniel E. Bender and Jana K. Lipman, Making the Empire Work: Labor and United States Imperialism (New York: NYU Press, 2015), 244; Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Knopf, 2009), 380–81; Cindy Hahamovitch, No Man’s Land: Jamaican Guestworkers in America and the Global History of Deportable Labor (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2011), 31–32.

7. Newspaper headlines from 1942 read: “Peonage Story Told by Victims: Tell of Mistreatment on Florida Sugar Plantation,” “Sugar Firm Officials Indicted on Charges of Enslaving Workers: Florida Sheriff Accused of Using Prisoners on His Farm without Pay,” and “Escaped ‘Slavery’ Farm.”

8. Rasmussen, History, 249.

9. Account based on ibid., 254.

10. Ibid., 254–55.

11. Ibid., 256.

12. In a May 11, 1943, memorandum from George W. Hill, special assistant to the deputy administrator of the WFA, to Conrad Taeuber, acting chief, Division of Farm Population and Rural Welfare, Bureau of Agricultural Economics, Hill states: “The importation of Negro workers from Jamaica presented certain difficulties. It was recognized that although these Jamaicans were members of the Negro race, their customs and social patterns differ from those of many of the Negroes of the United States and it was further reported that there was little race distinction in Jamaica.” Rasmussen, History, 258.

13. In a May 17, 1943, memorandum from George W. Hill to Lieutenant Colonel Jay L. Taylor, deputy administrator of the WFA, Hill states: “However, experience with these workers has been that States’ Negroes are more amenable to acceptance of the traditional local racial differentials. Summing up all the evidence, I cannot get anyone very enthusiastic over the idea of placing Jamaicans where employers are accustomed to using States’ Negroes.” Rasmussen, History, 258.

14. Ashley Jackson, The British Empire and the Second World War (New York: Hambeldon Continuum, 2006), 93.

15. The Caribbean islands that constitute the British West Indies did not secure independence from Great Britain until 1962 (Jamaica), 1966 (Barbados), and 1973 (Bahamas). British Virgin Islands, St. Kitts, Saint Lucia, and the remaining British Caribbean islands and Central American holdings were minimal contributors to this migrant stream.

16. US Congress, Public Law 414 (June 27, 1952), http://library.uwb.edu/static/USimmigration/66%20stat%20163.pdf.

17. See Josh DeWind, Tom Seidl, and Janet Shenk, “Contract Labor in US Agriculture: The West Indian Cane Cutters in Florida,” in Peasants and Proletarians: The Struggles of Third World Workers, ed. Robin Cohen, Peter C. W. Gutkind, and Phyllis Brazier (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1979), 380–96.

18. US Congress, Public Law 78 (July 12, 1951), http://library.uwb.edu/static/usimmigration/65%20stat%20119.pdf.

19. Don Liberio, “Life Story of Don Liberio,” interview by the author, Fresno, California, 1997.

20. See Mize, Invisible Workers, 68–73.

21. An initial provision stated, “Mexican contract workers would not engage in US military service.” Beyond the focus of this present analysis, it was designed to quell Mexican popular discontent and apprehensions about how earlier uses (during World War I) of Mexican labor were thought to have occurred during what Kiser and Kiser refer to as the First Bracero Program. George C. Kiser and Martha W. Kiser, Mexican Workers in the United States (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1979). Without government interference, US growers directly recruited laborers from Mexico to meet wartime labor shortages. After World War I, the citizens of Mexico heard rumors that Mexican laborers, brought to the United States to work in the agricultural fields, were forced into military service for the war effort. My research of this contention revealed no evidence of this practice. Both the governments of the United States and Mexico denied that the practice ever occurred. Nevertheless, to quell Mexican popular apprehensiveness and allay fears, the initial article was agreed upon by both governments.

22. Juan Ramon Garcia highlights Bracero Program provisions in Operation Wetback: The Mass Deportation of Mexican Undocumented Workers in 1954 (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 1980), 24.

23. Labor shortages existed, according to Barbara Driscoll, The Tracks North (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999). See also Robert C. Jones, Mexican War Workers in the US: The Mexican-US Manpower Recruiting Program and Its Operation (Washington DC: Pan American Union, 1945). Yet the claim of a shortage of domestic labor is a source of contention in the literature. Those who disagree with this prognosis and see braceros as used by growers to undercut domestic wages include Henry Pope Anderson and Ernesto Galarza. See Anderson, Fields of Bondage (Berkeley, Calif.: Mimeographed, 1963), and The Bracero Program in California (New York: Arno, 1976 [1961]); Galarza, Strangers in Our Fields (Washington, DC: United States Section, Joint United States-Mexico Trade Union Committee, 1956), and Merchants of Labor: The Mexican Bracero History (Santa Barbara, Calif.: McNally and Loftin, 1964).

24. Kiser and Kiser, Mexican Workers.

25. Señor Palmas, interview by author, San Luis Valley, Colorado, 1997.

26. Don Francisco, “Life story of Don Francisco,” interview by author, Fresno, California, 1997.

27. Don Andres, “Life story of Don Andres,” interview by Sergio Chavez, US-Mexico border, 2005.

28. Galarza, Merchants.

29. Don Antoñio, “Life story of Don Antoñio,” interview by author, Fresno, CA, 1997.

30. United Farm Workers (UFW), El Malcriado: Trade Journal of the United Farm Workers 1 (1996): 18.

31. David Gutierrez, Walls and Mirrors: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants, and the Politics of Ethnicity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

32. Philip Martin, “The Bracero Program: Was It a Failure?” History News Network (2006), historynewsnetwork.org/article/27336; Kitty Calavita, Inside the State: The Bracero Program, Immigration, and the I.N.S. (NY: Routledge Press, 2010).

33. DeWind, Seidl, and Shenk, “Contract Labor,” 386.

34. Ibid., 383.

35. Ibid., 392.

36. Robert Williams, “The H-2A Program,” panelist, presented at the National Conference on Migrant and Seasonal Farmworkers, Denver, Colo., May 9–13, 1993.

37. For details of the labor peace accords, see Hahamovitch, No Man’s Land, 220.

38. David Griffith, American Guestworkers: Jamaicans and Mexicans in the US Labor Market (State College: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007), 70.

39. US Congress, Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, http://library.uwb.edu/static/usimmigration/100%20stat%203359.pdf.

40. US Department of Labor, Office of Foreign Labor Certification 2014 Annual Report (Washington DC: Employment and Training Administration, Office of Foreign Labor Certification, 2015), 34, https://www.foreignlaborcert.doleta.gov/pdf/OFLC_Annual_Report_FY2014.pdf.

41. Rafael Alarcón, “Skilled Immigrants and Cerebreros: Foreign-Born Engineers and Scientists in the High Technology Industry of Silicon Valley,” in Immigration Research for a New Century: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, ed. Nancy Foner, Rubén Rumbaut, and Steven J. Gold (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2000).

42. US Department of Labor. The Foreign Labor Certification Report: International Talent Helping Meet Employer Demand (Washington DC: Employment and Training Administration, Office of Foreign Labor Certification, 2007), https://www.foreignlaborcert.doleta.gov/pdf/FY2007_OFLCPerformanceRpt.pdf.

43. US Department of Labor, The Foreign Labor Certification Report: 2009 Data, Trends and Highlights across Programs and States (Washington DC: Employment and Training Administration, Office of Foreign Labor Certification, 2009), http://www.foreignlaborcert.doleta.gov/pdf/2009_Annual_Report.pdf.