The Undertow of Reforming Immigration

Over the two decades between the end of World War II and the passage of the Immigration Act of 1965, the agents of immigration reform were checked by a strong undertow that kept them just short of achieving their objectives. The establishment of the national origins quota system in the 1920s was driven by an ideology of deserving (distinguishing people by class or selectivity), a belief in ethnic and racial superiority (eugenics and racism), and desire of the Southern and rural regions of the country to retain control over the Congress (power or apportionment politics). Demographic data and public-opinion surveys from this period illustrate a changing citizenry that challenged these three factors.1

In the years leading up to the Immigration Act of 1965, a growing sense of citizenship as well as an actual increase in naturalization among immigrant groups was shifting the balance. More precisely, the naturalization rate (in other words, percent of foreign-born residents who become US citizens) rose from just over half (52 percent) in 1920 to over three-quarters (80 percent) in 1950. Just as the accomplishments of immigrants and successes of their children were directly challenging old notions of selectivity and racial superiority, the electoral clout of naturalized immigrants and their children was beginning to alter the political landscape.

Coupled with the increasing civic engagement of immigrants was a broader societal push toward equality in mid-twentieth-century United States. There is considerable scholarship on how the war against fascism abroad turned the mirror on inequality in the United States and fueled campaigns for civil rights, workers’ rights, women’s rights, and other struggles for equality. At issue was how long the undertow of beliefs in a deserving class, race, and ethnic superiority and entrenched political power would hold back the societal and political currents for equality.2

Opportunities and Challenges of the Postwar Period

The immediate postwar period was a heady time for the nation. The United States and its allies had defeated the powers of fascism and, in the process, had risen out of the Great Depression. Sacrifice and austerity gave way to pent-up consumer demand, and the federal government committed to a full-employment economy. Immigrant workers were energizing the American labor movement, most notably with Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), and flexing political muscle that made labor unions one of the most powerful constituencies of postwar liberalism. By all indications, the timing seemed optimal for the United States to liberalize its immigration policies.

In 1945 the House Select Committee on Postwar Immigration considered the option to end racial discrimination in immigration during its deliberations. This move came at the same time when liberals fought for racial equality in a variety of areas, most notably in the arena of employment.3 Committee counsel Thomas Cooley reported that support for ending racial discrimination was expressed consistently in hearings around the country. “Numerous recommendations to this effect were made by a wide selection of witnesses in all parts of the country. They were explicitly opposed by west coast organizations specializing in opposition to the immigration or naturalization of orientals.” The recommendations that arose from the hearings included an end to racial discrimination in immigration and naturalization laws and a retention of quotas, provided the quotas were assigned on a nondiscriminatory basis. Despite the outpouring of support to end race-based admissions at the hearings, the committee did not endorse an end to the national-origins quota law.4

As Europe filled with millions of displaced persons after World War II, it became abundantly clear that most in Congress were wedded to retaining national origins as a basis of immigrant admissions. Even though the Displaced Persons Act of 1948 provided for the admission of four hundred thousand refugees, it did so within the framework of the national-origins quotas. More precisely, the admissions of displaced persons were “mortgaged” against 50 percent of their home countries’ quotas. There was no groundswell for increased immigration, and opinion polls estimated that only 40 percent of the public supported admitting two hundred thousand refugees displaced after World War II.5

While there was a consensus among liberals that race- or national-origins-based admissions policies had to go, there was not a clear alternative to current law. No major case was being made for a return to immigrant admissions limited only by the grounds for exclusions. There was some support for increasing the total levels but few voices for removing numerical limits. Designing an alternative system for allocating visas fairly proved to be a challenge for the 1950s.

In 1947, Senate Resolution 137 authorized the funding for a “full and complete investigation” of immigration, which included field investigations in various locations across Europe and the Western Hemisphere.6 Conservative senator Pat McCarran (D-NV), chair of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, led the Senate immigration investigation. Although the Senate Special Subcommittee to Investigate Immigration and Naturalization did not publish any hearings, it did produce an official report in 1950 (Senate Report 1515) that numbered 985 pages. Senate Report 1515 concluded that the national-origins quotas served well as a method for the numerical restriction of immigration, but the report criticized the national-origins quotas for not admitting the proper mix of white people. More precisely, the report stated that “only about half of the anticipated proportion of immigrants have come from northern and western Europe, while twice the contemplated proportion have come from southern and eastern Europe.” The report concluded, “As a method of preserving the relationship between the various elements in our white population, the national origins system has not been as effective.” While Senate Report 1515 was an affront to the liberal movement for equality, fairness, and expansive citizenry, it is unclear if many people actually read it.7

When Congress did pass a reform measure in 1952, it retained this basic system for immigration restriction despite criticisms of the national origins system and its privileging of immigrants from northern and western Europe. The McCarran-Walter legislation based the annual number of immigrant visas issued each year on the 1920 census and set the level at 0.16 percent of the 1920 population of the United States. The computation resulted in just under 155,000 immigrants annually. The legislation formally removed the racial bars on immigrant admissions and gave the minimum quota to all countries outside of the Western Hemisphere. It also retained the policy of unlimited immigration from the Western Hemisphere, with inclusion of the Asia-Pacific Triangle language limiting those of Asian descent. Displaced persons continued to be counted under the national-origins quotas, as the effort to remove the mortgages failed again. The resulting national-origins quotas were quite similar to those in place before the passage of McCarran-Walter.

McCarran-Walter did, however, reform the way immigrant visas were distributed within each country’s quota. The preference system to allocated visas that McCarran-Walter established was as follows:

•50 percent (plus rollover from unused preferences below) to persons of high education, technical training, specialized experience, and exceptional ability;

•30 percent to parents of US citizens at least twenty-one years old;

•20 percent to spouses and children of LPRs; and, any remaining (up to 25 percent) for siblings, sons, and daughters of US citizens.

For the first time, US immigration policy was prioritizing the immigration of highly skilled individuals. The significance of this shift in policy grew in the coming years. From this point forward, business interests and organized labor had even larger stakes in the immigration debate. Given the importance of immigrant workers to both union mobilization and US employers, their power as a constituency had more potential.

Finally, the McCarran-Walter Act, by removing the racial bars to citizenship, opened the door for all foreign nationals with legal permanent-resident status to seek citizenship. Perhaps as many as thirty thousand Asians previously barred from naturalization became US citizens by 1955. More meaningful than the numbers of people naturalized in the immediate aftermath is the principle that all persons, regardless of race, were therefore eligible to become citizens under the law.8

Building Steam for Equal Treatment

The watershed moment in the drive to end national-origin admissions came when President Harry Truman vetoed the McCarran-Walter Act. Many had assumed Truman would sign the legislation. Neither Attorney General McGranery nor Secretary of State Dean Acheson had publically voiced opposition to the legislation, and both submitted memoranda to the president recommending that he sign it. McGranery acknowledged that the legislation contained objectionable provisions, but he also concluded that it was an improvement over existing law. The State Department characterized the bill as a “much-needed and long overdue codification” and referred to the provisions it would add as “improvements and liberalizations.”9

The Bureau of the Budget, however, offered President Truman a biting analysis of the legislation heading for his desk. The analysis attached to the Budget Bureau director’s memorandum pointed to the racially based restrictions placed on the immigration of Asians by addition of the Asia-Pacific Triangle provision. The analysis also cited the “racially discriminatory” treatment of colonial immigrants, particularly “Negroes from the West Indies.”10

On June 25, 1952, the President sent Congress a veto message that was scathing and vigorous; moreover, it took aim directly at the national-origins quota laws. “The greatest vice of the present quota system, however, is that it discriminates, deliberately and intentionally, against many of the peoples of the world.” The message went on to detail what the administration considered the discriminatory aspects of the law, citing its treatment of Asians, Italians, Greeks, Poles, Rumanians, Yugoslavs, Ukrainians, and Hungarians. Truman continued to argue that “the basis of this quota system was false and unworthy in 1924. It is even worse now. At the present time, this quota system keeps out the very people we want to bring in. It is incredible to me that, in this year of 1952, we should again be enacting into law such a slur on the patriotism, the capacity, and the decency of a large part of our citizenry.” As he drew to a conclusion, Truman observed:

In no other realm of our national life are we so hampered and stultified by the dead hand of the past as we are in this field of immigration. We do not limit our cities to their 1920 boundaries; we do not hold corporations to their 1920 capitalizations; we welcome progress and change to meet changing condition in every sphere of life except in the field of immigration.11

Analysis of the roll-call vote on whether to override or sustain the president’s veto reveals the importance of the immigrants as new or prospective citizens. More precisely, the proportion of the state or district’s population that was foreign-born offers an explanation for the senators and representatives who deviated from their party’s position. The Senate vote was quite close, and Senate Republicans who voted to sustain Truman’s veto were from states that had foreign-born populations that were 5.6 percent or greater. They largely represented the East Coast or Mid-Atlantic regions of the country. Conversely, Senate Democrats who voted to override Truman’s veto were overwhelmingly from the states with 1.7 percent or fewer foreign-born constituents. The patterns on the House roll-call vote on Truman’s veto are quite similar to the Senate pattern. Those House Republicans who voted to sustain Truman’s veto tended to be from states with higher percentages of foreign-born residents, and House Democrats who voted to override Truman’s veto were more likely to be from the Southern states with very few foreign-born residents.

In his veto message, Truman had asked Congress to establish a commission to conduct a careful reexamination of immigration law. When Congress did not act, the president created a special Commission on Immigration and Naturalization on September 2, 1952, tasked with bringing immigration law “into line with our national ideals and our foreign policy.”12 The Truman Commission held a series of hearings across the country and sought the voices of local witnesses. More precisely, the commission met in eleven cities and heard more than four hundred testimonies. The commission further received more than 230 written statements after the hearings were concluded. As a result, the Truman Commission garnered a fair amount of local media coverage as well as national press. The visible role of the commission no doubt played a key part in raising public awareness of immigration issues.13

The Truman Commission recommended that the national-origins quota be abolished and that immigrants be admitted without regard to national origin, race, color, or creed. That meant the end of the exemption of the Western Hemisphere countries from numerical limits. It further recommended that the annual level of immigration be set at 250,000, which was comparable to current levels when the Western Hemisphere flows were added to the 155,000-quota limit. The Truman Commission further recommended that the 250,000 visas be distributed on the basis of “unified” flexible quotas according to the needs of the United States.

Competing Views of Public Opinion

Opponents of the McCarran-Walter Act expressed confidence that the majority of the public supported reforming the law. During hearings before the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration and Naturalization in the summer of 1955, witnesses cited a recently released Gallup survey reporting that more than half of those interviewed who were familiar with the McCarran-Walter Act thought it should be changed. Of those who thought the law should be changed, Gallup reported that 68 percent favored making the law more liberal. Only 26 percent (of the 53 percent who supported changing the law) expressed the view that the law should be made stricter.14

Figure 1. Gallup Survey of Support for McCarran-Walter Act in 1955

Source: “Prospects for Immigration Amendments,” by Harry N. Rosenfield, Law and Contemporary Problems, Spring 1956.

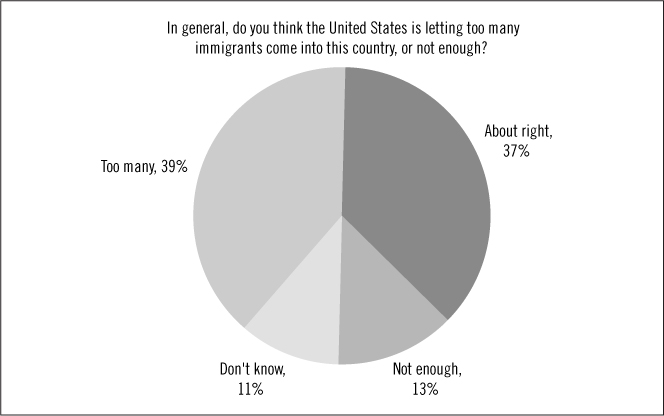

In contrast to the Gallup survey cited by advocates for reform, the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) found in April 1955 that only 13 percent of those surveyed thought that immigration levels should be increased. The proportion who said immigration levels were “about right” (37 percent) was comparable to those who said the United States was admitting too many immigrants (39 percent). Figure 2 displays these data.15

How questions are worded is obviously critical to these differing results, as one survey asked about liberalizing the law and the other asked about immigration levels. No doubt there were individuals surveyed by either Gallup or NORC who opposed the national-origins system but did not want to increase immigration. Conversely, some might have approved of increased levels but not repealing the national origins system. Also, when the calculation of 68 percent of the 53 percent is completed, the result is that 36 percent of Gallup’s respondents overall favor liberalizing the McCarran-Walter Act.

Although the surveys did not directly ask a question about national origins or diversity, NORC takes their survey a bit further by asking two follow-up questions of respondents who said they disapproved of admitting “so many.” The majority of the 39 percent who supported reducing immigration gave economic reasons for their position, as figure 3 illustrates.16 Of the economic reasons cited—competition for jobs—led the opposition to immigration. Lack of housing and concern that wages would be depressed were other economic reasons given. Only about 7 percent overall said that immigrants were undesirable, and another 3 percent said that there were “enough immigrants here now.”17

Figure 2. NORC Survey of Public Support for Increased Immigration in 1955

Source: National Opinion Research Center, April, 1955.

Figure 3. Top Reasons Given for Reducing Immigration in 1955

Source: National Opinion Research Center, April 1955.

In response to NORC’s asking those who disapproved of admitting “so many” immigrants what particular groups or nationalities they had in mind, it was apparent that memories of the war and fears of communism were the leading factors. As figure 4 shows, communist countries and the former Axis powers of Germany, Japan, and Italy led as the least-favored source countries for immigrants, reflecting a more political or ideological approach to restriction. Rather striking, however, was the comparably small percentage of respondents who otherwise identified groups or nationalities as prompting their disapproval. For example, only 3 percent mentioned Mexicans and Latin Americans, and only 2 percent listed Eastern Europeans, Jews, and Ukrainians. These data may have reflected the shifting social norms against expressions of bigotry and prejudice rather than an actual change in attitudes toward immigrants.18

Figure 4. NORC: Nationalities Opposed by Those Who Would Reduce Immigration in 1955

Source: National Opinion Research Center, April 1955.

1960 Opens

Critical to the growing civic participation of immigrants was the establishment of the nonpartisan American Citizenship and Immigration Conference (ACIC) in 1960. ACIC was a merger of the National Council on Naturalization and Citizenship and the American Immigration Conference. This umbrella group brought together the ethnic groups, religious entities, and civic organizations that sought immigration reform. The American Immigration Conference had been an association of thirty-one immigration-related organizations and agencies that advocated for a “nondiscriminatory alternative” to the existing national-origins quota system. The National Council on Naturalization and Citizenship had been an association of organizations and individuals who advocated for “humane, uniform, and simple” immigration laws. Ruth Z. Murphy, who had founded the American Immigration Conference earlier, led the new ACIC in its efforts to change immigration laws. A strong institutional structure for immigrants’ civic engagement was fully in place.19

In terms of public opinion, however, foreign policy dominated the top concerns of the citizenry in 1960. When Gallup asked a sample of the American people what they considered to be the top problem facing the nation, the threat of war and keeping the peace led the list of concerns, averaging 20 percent. Relations with Russia and general foreign relations followed closely, each averaging 15 percent. Racial problems ranked first among the domestic policy issues at 7 percent, with unemployment and inflation rounding out the top ten.20

The 1960s also began with nonviolent civil rights protests in the South. In February, black students staged a sit-in at a whites-only Woolworth’s lunch counter in downtown Greensboro, North Carolina. Six months later, that same lunch counter served its first meal to a black customer. National coverage of the civil rights movement was increasing, and an emerging leader of the movement, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested at an Atlanta sit-in that October.

The seeds of a Latino or Chicano rights movement were sprouting in the early 1960s as well. For example, Edward Roybal was the founding president of the Mexican American Political Association in 1960 and was elected to the US Congress from California in 1962. Henry Gonzalez co-chaired Viva Kennedy in 1960, won a special election to the US Congress from Texas in November 1961, and went on to expose the exploitation of the migrant workers under the Bracero Program. An emerging migrant-workers’ rights movement led by agricultural workers of immigrant descent was gaining traction. Dolores Huerta, who would later co-found the United Farm Workers with César Chávez, established the Agricultural Workers Association in 1960.

There was not a national immigrant rights movement per se, as most of the immigrant groups were organized by nationality. The bulk of the ethnic organizations in the United States were focused on changing the immigrant admissions law (rather than on the rights of immigrants already in the United States). These ethnic and religious groups formed the core of the immigration reform movement. One of the most active was the American Committee on Italian Immigration, which had about 120 chapters across the country. Similarly, the American Jewish Committee and the B’nai B’rith played prominent roles and had offices around the country. The American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association, originally formed in the 1920s to combat discrimination, had more than four hundred local chapters by the early 1960s. The ACIC worked to engage these disparate nationality groups as part of its broader efforts to expand citizenry.

Significance of the 1960 Presidential Election

Senator John Kennedy had championed immigration reform for many years. It was a key campaign issue when he defeated Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. for Senate in 1952. When Kennedy chaired the Immigration Subcommittee in the Senate, he managed to accomplish what other supporters of immigration reform had been unable to do—co-sponsor legislation (with Congressman Francis “Tad” Walter [D-PA]) that liberalized immigration law. For his running mate, Kennedy chose Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson (D-TX) who had come in second to him for the Democratic nomination in the convention voting. Johnson’s position on immigration had evolved from supporting the McCarran-Walter Act in 1952 to crafting the Senate-passed immigration reform bill in 1956. Kennedy chose his rival Johnson with the objective of gaining electoral votes in the South.

The 1960 presidential election was one of the closest in the twentieth century. Kennedy won with only 0.17 percent of the popular vote. Kennedy’s Catholic religion was a major issue in the 1960 race, and much has since been written about whether the Catholic vote pushed Kennedy over the top.21 The Kennedy-Johnson ticket exceeded expectations in Johnson’s home state of Texas, particularly along the immigrant-rich Rio Grande Valley. The turnout in Chicago, coordinated by Mayor Richard Daley Sr., was similarly impressive in precincts with ethnic voters, enabling Kennedy to carry the state by a slim margin. Indeed, turnout in the major urban areas was decisive for the Democrats. At this point in history, the correlation between the Catholic faith and foreign-born or first-generation ethnic Americans was significant. Published research has shown that the Kennedy-Johnson ticket made much greater gains with the Catholic vote than the Nixon-Lodge ticket did with the Protestant vote. It is safe to assume that voters of foreign stock were instrumental in this election.22

Kennedy’s victory was pivotal in the eyes of immigration reformers. They had worked with him on reform efforts while he served in the Senate when he opined, “Perhaps the most blatant piece of discrimination in our nation’s history is the so-called National Origins formula.” The relationship between Kennedy and the immigration reform movement was arguably symbiotic: Kennedy gained their electoral support, and the immigration reformers increased their political access.23

The post-election euphoria among immigration reformers was tempered by the situation in Congress. The bulwarks against immigration reform—Senate Judiciary Chairman James Eastland (D-MS) and House Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration Chairman Tad Walter (D-PA)—retained their positions of power over immigration legislation. The president continued to be respectful of Congressman Walter and also worked to maintain cordial relationship with Senator Eastland.24

As he had many times before, Judiciary Chairman Emanuel Celler introduced legislation abolishing the national-origins quota system. His bill in the 88th Congress (H.R. 3926) would have increased the ceiling on immigration to 250,000 annually and would have allocated these visas accordingly: 40 percent family reunification; 20 percent needed occupational skills; 20 percent refugee-asylee; and 20 percent other resettlement. By the 1960s, Celler no longer proposed to place immigrants from Western Hemisphere countries under the numerical limits.25

Across the US Capitol in the Senate, the architect of immigration reform became Philip Hart (D-MI). Hart came with a strong record on civil rights and labor issues and rather naturally took up the cause of immigration reform once in the Senate. In 1962, Hart had introduced legislation (S. 3043) with bipartisan support that would have abolished the national-origins quota system and increased the ceiling on immigration to 250,000. Up to fifty thousand visas were set aside for refugees. The Hart bill also would have added to the nonquota (in other words, unlimited) category those immigrants whom the Secretary of Labor deemed were urgently needed because of high education, specialized experience, and technical training. Immediate relatives of U. S. citizens and immigrants from Western Hemisphere countries were also unlimited under S. 3043, and the bill would have revised the law to include Jamaica, Trinidad, and Tobago among the Western Hemisphere nations.

It was not until July 1963 that the Kennedy administration sent a proposal to Congress that sought a total phase out of the national-origins quota system over five years. In contrast to Celler’s and Hart’s legislation, the administration proposed to only raise the ceiling to 165,000. The administration bill also picked up a provision from Hart’s bill that became known as the per-country caps. The bills stated that not more than 10 percent of the total number of visas allocated by the preference system could go to any one country. Celler had a comparable provision, but he had set his per-country cap at 15 percent of the total. The administration bill shared a provision with Senator Hart’s earlier legislation that redefined the Western Hemisphere exemption to include all countries and adjacent islands.26

In September 1963, more than half of the American public surveyed by Gallup stated that racial problems (including integration, segregation, and civil rights) were the top problems facing the nation. Racial problems stayed first on the list throughout 1964. Civil rights had been an urgent issue for the Democratic Party for several years, but it laid bare the wide schism between the Southern Democrats and the rest of the party on matters of race. As House Judiciary Chairman Emanuel Celler and Senator Phil Hart were the leading legislators on civil rights and voting rights legislation, their attention was squarely focused on moving these bills before taking up immigration.27

The assassination of President Kennedy devastated a nation that watched much of the tragedy unfold on television. The country in general grieved the loss of the charismatic commander in chief, and proponents of immigration reform in particular mourned the death of a president who had championed their cause. These proponents were very suspicious of the newly sworn-in President Lyndon Johnson because he had voted for the McCarran-Walter Act and because he was from Texas—a state infamous for being inhospitable to immigrants. Defenders of the immigration status quo were equally suspicious of Johnson because he had a reputation of squeezing votes out of members of Congress in order to achieve his objectives, including the immigration amendment he moved through the Senate in 1956.

As discussed at the outset, the establishment of the national-origins quota system was driven by selectivity, race, and power. Now, the justifications for abolishing it grew out of a basic sense of fairness (selectivity), equality of treatment (race), and representational politics (power). The legislative alternative was one based on the contributions and the potential of the prospective immigrant rather than the country of birth. In other words, merit would replace class and family reunification would replace race. The political incentives for Democrats were found in the foreign stock voters who disproportionately supported them, completing the third element—power.

The increasing civic participation of immigrants was working in the Democrats’ favor. By 1964, a record proportion of the foreign-born population had become citizens. Naturalization data from the former Immigration and Naturalization Service indicated that almost 1.7 million immigrants had become citizens in the years 1951 to 1964. Presidential advisor Myer “Mike” Feldman prepared detailed maps of the United States by the percentage of foreign stock. Feldman used these census data to prepare an extensive list of members of Congress who represented districts with noteworthy percentages of foreign-stock residents. Feldman added the names of the member’s administrative assistant (lead staffer) to create a very useful targeting tool for legislative support as well as get-out-the-vote drives.28

Republicans Divided in 1964

The chasm within the Democratic Party on immigration reform was apparent for decades, but the Republican Party of this period also had a deep divide over immigration policy. While the rift in the Democratic Party was largely regional, the Republican split was more nuanced. Most of the Republicans who supported immigration reform also advocated for civil rights legislation, broader funding of education, and an activist federal role to bolster the US economy. The conservative wing of the Republican Party painted a picture of pro-immigration Republicans as elites who were out of touch with average Americans.

In 1964, Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater won the Republican nomination for president, heralding a sharp turn to the right in the Republican Party. The platform called for reinstating the controversial Bracero Program for migrant agricultural workers from Mexico. As his running mate, Goldwater chose the chairman of the Republican National Committee, Congressman William Miller of New York, and it was Miller who made immigration an issue.

At an event on Labor Day in South Bend, Indiana, the Republican vice-presidential nominee warned that LBJ’s immigration bill would “completely abolish our selective system of immigration and instead open the floodgates.” He went on to suggest that immigrants would take jobs from the American workers. Rather than winning over the crowd of autoworkers who had suffered from major layoffs earlier in the year, Miller’s speech riled those in the audience of eastern and southern European backgrounds. Many Americans viewed the floodgates that Miller warned against opening as actual barriers keeping family members apart. The American Citizenship and Immigration Conference (ACIC) swung into action with letters to the Goldwater-Miller campaign and to the press. The AFL-CIO and its many affiliates responded that they supported the LBJ’s immigration proposal and were confident that it would not cost American workers’ their jobs. More than forty ethnic, religious, and civic organizations engaged in letter-writing campaigns against the speech. The outpouring of criticism of Miller’s anti-immigrant remarks illustrates just how much notions of citizenship were broadening to encompass people born abroad.29

A public-opinion poll taken in the midst of the controversy over Miller’s remarks found that the plurality (46 percent) of Americans surveyed in the fall of 1964 were content to keep the number of immigrants admitted each year at the existing level. More than one-third (38 percent) expressed the preference to decrease immigrant admissions, as figure 5 shows. Support for decreasing immigration levels held steady when compared to the 1955 NORC survey, in which 39 percent thought immigration levels were too high. Only 6 percent of those surveyed supported increased levels of immigration, a proportion down from 13 percent in 1955.30

Those people who were upset with Miller’s speech might have heard his remarks as anti-immigrant rather than as a critique of the administration’s bill. There was clearly no groundswell to increase immigration, but Miller’s comments might have served as a “dog whistle” that was intended to motivate certain anti-immigrant voters. Foreign-stock voters heard the whistle too, energizing an important base in the Democratic party.

Lyndon Johnson won by a landslide, winning 61.1 percent of the votes cast and carrying forty-four states and the District of Columbia. Barry Goldwater won only Arizona (his home state) and the southern states of Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina. Pro-immigration Republicans such as Keating also lost in the Democratic sweep. The Johnson-Humphrey coattails brought in a net gain of thirty-six seats for the Democrats in the House, which provided them with a two-thirds majority. Similarly, the Democrats, by winning a net gain of two seats in the Senate also had a two-thirds majority. It appeared that there would be a sufficient number of Democratic Senators and Congressmen to place the “Great Society” agenda, including immigration reform, within reach.

Figure 5. Public Attitudes toward Immigration Levels, September 1964

Source: Gallup, September 1964.

Shaping Public Opinion

In his first State of the Union Address, President Johnson linked immigration reform to his civil rights agenda. While distinguishing it from civil rights legislation, he made clear that he considered the existing immigration system to be discriminatory. Johnson pitted the needed skills of the immigrants and the commitment to family reunification against the national-origins quotas. These principles were in the legislative package that Kennedy had sent to Congress in 1963, but Johnson had sharpened the framing of the issues to those of fairness, equality, and an expanding citizenry.

Within days of his State of the Union, President Johnson brought representatives of the leading organizations concerned with immigration and refugee issues to the White House. More than three dozen private citizens representing a range of faith-based, secular, and organized-labor groups gathered in the Cabinet Room with hand-picked senators, representatives and key administration officials. Civic engagement was at full throttle, as immigrant group leaders were literally “at the table” with the president, senators, and representatives who were tasked with rewriting immigration law.

Well aware of the significance of the moment, the president also staged a press conference at the meeting. Johnson opened by stating that existing immigration law had “overtones of discrimination,” opting to be a bit less strident than other advocates for reform. He echoed the phrase from his State of the Union: “We should ask those who seek to immigrate now, what can you do for our country? But we ought never to ask, in what country were you born?” With television cameras running, the president made clear that he supported an expanded citizenry based upon equal treatment.31

The undertow of political forces thwarting immigration reform picked up the gauntlet the president had thrown down to them. During a hearing that the national press extensively covered, Senator Sam Ervin questioned Secretary of State Dean Rusk on immigration reform. As Ervin began his remarks, he was echoing the “mirror of America” theme that it was only fair to favor northern and western Europeans in the quota law. Ervin then said the reform legislation discriminated against northern Europeans because it would treat them the same as Ethiopians. Ervin went on to state, “I don’t know of any contributions that Ethiopia has made to the making of America.” Ervin’s blatant racism was another affront to equality, fairness, and expansive citizenry and a clear message to the president and all proponents of reform.32

There was significant variation in media coverage of Ervin’s comments, largely centered on whether the article included Ervin’s comment about Ethiopia or merely his assertion that the bill would discriminate against northern Europeans. Some of the coverage also included Senator Jacob Javits’s outburst that he could not “sit still for this proposition uttered by my colleague from North Carolina that ethnic groups that came from Northern Europe and England made America.” The Washington Post featured the hearing as a clash between the “descendent of Anglo-Saxon slave owners” and the “son of New York Jewish immigrants.” Whether the particular newspaper included Rusk’s response to Ervin was especially telling. The Secretary of State had replied that “there’s no question but that Negroes have contributed enormously to American life.” Sadly, few in the media included Rusk’s reply.33

Given the auspicious start of the legislative campaign for immigration legislation, supporters of immigration reform were very disheartened when Louis Harris published the results of his nationwide survey disclosing that LBJ’s proposal to ease immigration laws was opposed by a 2 to 1 margin. The administration and congressional supporters knew that there was little public support for increasing immigration levels and had considered the increased levels in their proposal to be modest.

Equally troubling was Harris’s analysis of what drove the anti-immigrant opinions. Harris observed that “part of the reason for the reluctance of Americans to lower the barriers to immigration obviously rests in the aversion many Americans express to people from countries covering over three-quarters of the world’s population.” Harris went on to list the countries and regions considered least desirable sources for immigrants, a list topped by Russia, with Asia and the Middle East as second and third, respectively.34

The Harris poll results garnered wide press coverage beyond the initial article in the Washington Post. The poll showed that even in the proverbial strongholds of immigration reform—the cities and the East—support for easing immigration law was less than 50 percent of those surveyed (figure 6). Defenders of the status quo were quite pleased by the results and were generous in referencing the survey in their speeches and commentary.35

Figure 6. Public Attitudes on Increased Immigration, May 1965

Source: Harris, May 1965.

The single bright spot in the Harris poll results from May 1965 was that only 29 percent of those interviewed supported the national-origins system, compared with 36 percent who favored basing immigrant admissions more on the skills of the individual (figure 7). Almost an equal portion expressed the view that it made no difference or that they were not sure. The task for immigration reformers was to shift as much as possible of the remaining one-third of the public to their side of the issue. Clearly, the target groups were the indifferent and the undecided.

Grassroots Campaign to Pass the Bill

No one knew better than Emanuel Celler that a major communication campaign was needed if immigration legislation was going to move forward. Celler acknowledged, “There is not a burning desire in the grassroots of this country to change our immigration policy.” As he spoke to a gathering of the leaders and grassroots of the immigration reform movement at an ACIC conference, Celler emphasized the need for a public-education campaign. “It must be the task of groups like yours … by force of logic to overcome the unrealistic fear which possesses so many people at the thought of any change in our immigration law.”36

Figure 7. Attitudes on Skills vs. Country of Origin, May 1965

Source: Harris, May 1965.

By spring 1965, a grassroots campaign was underway to gin up support for the legislation. The ACIC had long published monthly newsletters, but in May 1965 they also disseminated an “action kit” aimed at whipping up support for the legislation. ACIC member organizations held public meetings to discuss the administration’s bill across the country. Donald Anderson, director of Lutheran Immigration Service, reported to Chairman Celler that “these discussions have been with Jewish, Catholic, Protestant and labor groups.” Anderson concluded, “In all these discussions we have found complete acceptance of the President’s proposal—after it has been explained and studied.”37

In response to the controversy brought on by the Harris poll, the White House had reached out to the Gallup public-opinion-research firm to ask questions that were more finely tuned to the legislative options on the table. In turn, Gallup conducted a nationwide survey in June 1965 that yielded somewhat different findings than the Harris poll from a month earlier (figure 8). Although a majority of those interviewed continued to oppose any increases in overall immigration levels, a slim majority (51 percent) now favored skills-based admissions over the national-origins quota system.38

This survey further found that respondents who supported the national-origins quota law were largely the same individuals who favored decreasing levels of immigration. Gallup had performed special breakdowns of their data for the Johnson Administration that revealed that the responses to the questions were correlated. According to the internal analysis, Gallup found “a hard core 1/3 of the population who desire very restrictive immigration policies.”39

Figure 8. Attitudes on Skills vs. Country of Origin, June 1965

Source: Gallup, June 1965.

The administration was especially happy to learn that 71 percent of those surveyed by Gallup listed occupational skills as the most important criteria for admitting immigrants. Just over half (55 percent) of the respondents also included “relatives in the US” as one of the top criteria. Gallup analysts concluded that the results indicated “a clear mandate for a policy based upon occupational skills.” The strategy of emphasizing merit over national origins appeared to be a wise one.40

Surprisingly, little of the language on merit survived the final throes of the legislative process. Despite their shrinking political base, the forces of the undertow forced proponents of reform to focus on what they considered most critical and feasible at that time. Repealing the national-origins quota system always remained front and center. The centrality of this theme led to a majority of legislators on both sides of the aisle to vote for the final bill. By replacing the national-origin quotas with a system of per-country ceilings, the Immigration Act of 1965 enabled a more racially diverse and culturally vibrant flow of future citizens.41

Notes

1. This chapter draws on the October 2015 Kluge Lecture titled “The Struggle for Fairness” that the author gave while she was a fellow at the John C. Kluge Center at the US Library of Congress and from her forthcoming book on the legislative drive to end race-and ationality-based immigration in twentieth-century United States.

2. Campbell Gibson and Emily Lennon, Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-Born Population of the United States: 1850–1990, US Census Bureau, Population Division, table 11, 1999.

3. For example, President Truman joined liberals in pushing for an end to racial discrimination in hiring by arguing for a permanent authorization of the Fair Employment Practices Committee.

4. US House of Representatives, Hearings Pursuant to H. Res. 52 Authorizing a Study of Immigration and Naturalization Laws and Problems, part 3, July 3, 1945, 80–81.

5. In April 1948, the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago surveyed the public about the Displaced Persons legislation.

6. US Senate, Committee on the Judiciary, The Immigration and Naturalizations Systems of the United States, S. Rept. 81-1515, April 20, 1950.

7. Ibid., 430–32 and 445–46.

8. US Department of Justice, Annual Report of the Immigration and Naturalization Service for 1955, tables 38 and 39. See https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32435028570315;view=1up;seq=3.

9. Memorandum, “Department of State Views H.R. 5678 Immigration and Nationality Bill,” ca. May 1952, Presidential Papers of Harry S. Truman; Memorandum from Attorney General James McGranery to Frederick J. Lawton with Attachment, June 17, 1952, Presidential Papers of Harry S. Truman. See https://www.trumanlibrary.org/publicpapers.

10. Executive Office of the President, Bureau of the Budget, “Memorandum for the President,” by F. J. Lawton, May 9, 1952, Presidential Papers of Harry S. Truman.

11. Harry S. Truman, Veto of the McCarran-Walter Immigration Act, 82nd Congress, 2nd Session, House Document 520, June 25, 1952.

12. Memorandum from Julius C. C. Edelstein to Richard E. Neustadt with Attachments, June 28, 1952, Presidential Papers of Harry S. Truman; Stephen T. Wagner, “The Lingering Death of the National Origins Quota System: A Political History of United States Immigration Policy, 1952–1965,” PhD diss., Harvard University, October 1986, 41–42.

13. Public Papers of Harry S. Truman, Special Message to the Congress Transmitting Report of the President’s Commission on Immigration and Naturalization, January 13, 1953.

14. Harry N. Rosenfield, “Prospects for Immigration Amendments,” Law and Contemporary Problems, Spring 1956, 411.

15. National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago during April 1955, and based on personal interviews with a national adult sample of 1,226; data provided by the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, Cornell University.

16. The United States had experiencing a recession in 1953 that was brought under control by the end of 1954. John W. Sloan, Eisenhower and the Management of Prosperity (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1991); Saul Engelbourg, “The Council of Economic Advisors and the Recession of 1953–1954,” Business History Review 54, no. 2 (Summer, 1980).

17. National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago, during April 1955, and based on personal interviews with a national adult sample of 1,226; data provided by the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, Cornell University.

18. Ibid.

19. The American Immigration Conference formed in 1930, and the National Council on Naturalization and Citizenship formed in 1954.

20. Gallup (AIPO) polls from February 1960 through October 1960; data provided by the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, Cornell University.

21. Kennedy was only the second Catholic nominated to run for president and the first to win. New York Governor Al Smith, who lost in 1928, was the first Catholic nominated by a major party.

22. Philip Converse, “Religion and Politics: the 1960 Election,” in Angus Campbell, Philip Converse, Warren Miller, and Donald Stokes, Elections and the Political Order (Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley, 1966), 96–124; and Christopher P. Gilbert, The Impact of Churches on Political Behavior: An Empirical Study (Santa Barbara, Calif.: Praeger, 1993).

23. Wagner, Lingering Death, 119–121, 310; Betty Koed, “The Politics of Reform: Policymakers and the Immigration Act of 1965,” PhD diss., University of California, Santa Barbara, 1999, 75.

24. Meyer Feldman Personal Papers, box 96, JFK Presidential Library, Boston, Mass.

25. In terms of Western Hemisphere migration, Celler was more focused on efforts to end the Bracero Program with Mexico due to concerns of migrant worker exploitation.

26. Memorandum to the Acting Secretary of State from Abba Schwartz, June 25, 1963, copied to Gordon Chase at the White House June 25, 1963, Files of Gordon Chase, National Security files box 7, LBJ Presidential Library, Austin, Tex. S.2585/H.R. 6820 in 1953 had featured the per-country caps and had set the level at 10 percent of the total number of preference visas.

27. Gallup reported that 52 percent of those surveyed listed racial problems, integration, segregation and civil rights as the top issue. It was rare for any issue to be listed by more than half of those surveyed. Gallup (AIPO), September 1963; data provided by the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, Cornell University.

28. US Department of Justice, Annual Report of the Immigration and Naturalization Service for 1964, tables 42 and 44, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32435066733346; Personal Papers of Myer Feldman, box 96, JFK Presidential Library.

29. Dom Bonefede, “GOP to Limit Immigration—Miller,” Boston Globe, September 8, 1964, 8; Robert S. Boyd, “Miller Speech May Be Major Blunder,” Washington Post, September 17, 1964; Copy of letter to William Miller from Ruth Murphy, Papers of Emanuel Celler Papers, US Library of Congress (hereafter, Celler Papers, LOC), and Koed, Politics of Reform, 196–201.

30. Gallup AIPO, September 1964.

31. Office of the White House Press Secretary, “Remarks of the President to Representatives of Organizations Interested in Immigration and Refugee Matters,” January 13, 1964, Papers of President Lyndon B, Johnson, 1963–69, Immigration-Naturalization, box 1, LBJ Presidential Library.

32. John H. Averill, “Rusk Hit on Immigration Law Change,” Los Angeles Times, February 25, 1965; Andrew J. Glass, “Senate Racial Clash,” Boston Globe, February 25, 1965; “Who Built America,” Hartford Courant, March 1, 1965; “Ervin and Javits Clash at Hearing on Easing Immigration Restrictions,” Washington Post, February 25, 1965; Senate Judiciary Hearings, 61–63.

33. Senate Judiciary Hearings, 61–63.

34. Louis Harris, “US Public Is Opposed to Easing of Immigration Laws,” Washington Post, May 31, 1965; Memorandum from Larry O’Brien to Mike Manatos, June 4, 1965, White House Central File Collection, Larry O’Brien files, LBJ Presidential Library; Wagner, Lingering Death, 422–23.

35. Wagner, Lingering Death, 422–23.

36. Celler speech to American Citizenship and Immigration Conference, 1963, Celler Papers, LOC.

37. Letter to Emanuel Celler from Donald E. Anderson, June 15, 1965, Celler Papers, LOC.

38. Memo to Bill Moyers based on telephone conversation with Irving Crespi, July 21, 1965, Office Files of Bill Moyers, box 8, LBJ Presidential Library.

39. Ibid.

40. Ibid.

41. The legislation to reform immigration had actually gotten shorter, from 211 pages in 1953 to the twelve-page Immigration Act of 1965.