These breads are baked for special holidays or seasons – rich plum pudding, Christmas panettone, Russian Easter kulich – and are so out of the ordinary that they are often found only in expensive shops rather than home kitchens. love to make them for gifts because there is nothing you can buy commercially that will even come close to tasting like these special breads made at home.

Plum puddings, for example, appear daunting to most, whereas they are really quite simple to make once the ingredients are assembled. Your own will be far superior to any sold in shops. The word pudding is the English word for dessert, and this pudding is nothing like a creamy American-style pudding. Still, many wonder why anyone would want to make this particular dessert from scratch. What on earth is a pudding steamer? Does a plum pudding really contain plums? And where do you get them in the middle of winter?

Similar questions apply to other special breads. Isn’t a complicated panettone time-consuming to make? Will it taste like the Italian ones? What about candied fruits? Most are preserved and taste awful, so why use them?

I asked these same questions as a novice baker, but the first time I mixed the fruits, nuts, and spices together for a real plum pudding, I understood exactly why the process was so intriguing: the house was filled with the seductive fragrance of cinnamon, nutmeg, and cognac, and when I carried the flaming pudding to the Christmas table on its silver platter, my guests felt as though Tiny Tim were about to appear on Cratchit’s shoulder! With the first bite of real plum pudding, I finally understood why an entire nation reveres a dark heap of questionable ingredients steamed into the shape of half a bowling ball and weighing about the same. And so will you. Understand, that is, not weigh the same.

For breads as exotic as kulich with pashka, it helps to know some Russians to get excited about Russian Easter. The only reason I ever made this bread was because I met some wild new Russian friends and wanted to let them know how much I enjoyed meeting them and how fascinating I found their culture. After they were long gone, I used to celebrate Russian Easter every year, just for the hell of it, so that I could make this amazing bread and cheese combination that now I serve for our Easter, too.

Almost everyone has a curry recipe in his or her repertoire, but not everyone makes bread to go with it. Ever since I met my first Indian friends at college, I have been fascinated by Indian cooking: the spices, the thousands of different curries, the lovely breads – puris, chappati, naan – the relative lack of hard and fast culinary rules. In short, I adore the creativity that is encouraged by Indian cuisine. And, being a Philistine at heart, I was fascinated by the custom of eating with bread rather than a fork. (As an adult, which is a questionable statement in itself, I delight in eating with my hands and licking my plate – literally – and all those things children are not supposed to do, like running with scissors.) The gestalt of it drew me deeper and deeper into Indian cooking, until I was making so many curries that my husband begged me to start reading Norman Mailer or Walt Whitman instead of Bhagavad Gita and tomes on Indian cooking that were stacked up in the kitchen – anything that would get me back on the steak-and-potato track for a while. There is nothing like a good chappati with curry, and although these breads can be bought at Indian markets, they will never compete with your own.

When I was at Berkeley, I also met African students whose cooking was memorable for its exotic spices and unusual combinations. I was introduced to berberé, a paste of many flavours, and the marvellous cardamom bread Ye-wolo, which is made into a large, flat round to fit inside a basket woven expressly for it. I would like to have included the most exotic bread from every country, but alas, had to choose most carefully for lack of space.

For special occasions or to pep up an antipasto table, I have included little rolls scented with white truffle oil. White tartuffi, as they are so charmingly called in Italy, are for me the eighth wonder of the world. As a child, I was told the golden rule practically daily, and learned very soon that it does indeed work. Share and share alike was also thrown in for good measure, and I have always tried to adhere to both when a plate of either white truffles or black caviar is set before me and, unfortunately, others at the table. But at this point I lose all morality and my mother’s words disappear in the vapour. I eye the little black jewels as they are passed around from guest to guest, consciously and meticulously counting each one to make sure I have not been cheated of my share. As truffles are shaved over my steaming fettuccine, I have been known to grasp the waiter’s arm which holds the truffle shaver, forcefully retaining him for just a few moments longer than my allotted time, thereby blatantly cheating my dinner companion out of two or three of his own pungent slivers. When it comes to truffled anything, I am more than ruthless; I am dangerous. I keep truffle oil on hand as others keep salt in the shaker, to sprinkle over my focaccia for a special apperitivo accompaniment or to give subtle flavour to a roasting game hen. But I know there will come a day when my decadence will hit bottom and I will furtively pour a full jigger of it, all for myself, tossing it off as true Texan – I’ll have Urbani* 101, straight up, water back.

Who does not love breadsticks, if only for the pleasure of their snap or simply to fiddle with in restaurants? Some are good, many are tasteless, and while very few are memorable, all feel good under the teeth. It is very hard not to eat a breadstick, if only because there is always hope that the next one will be different from and better than the rest.

The ones you make in your kitchen will outshine any commercial ones. You will be amazed at how varied breadsticks can be; they are, after all, just long sticks of good crust, and what you put on them is only limited by imagination. Roll them in seeds, crushed nuts, cinnamon and sugar for breakfast, or brush them with scented olive oils or just plain melted butter for richness. I don’t think we have really tuned in to breadsticks in restaurants yet, but when we finally learn to make good ones, I am sure they will be the next trend. I predict that there will be duels between chefs, each brandishing his own signature sword of dough, and each munching on the other’s after they have called a draw. Children also love making breadsticks, and anything that engages a child in the kitchen has a very special place in my heart.

True plum pudding has never been as large a part of American holidays as it has been in the United Kingdom or other parts of Europe, but once you have tried this one, you will always want to include it on your holiday menu, if only for the lovely scent of marinating fruits. My husband counts the days until he has his Christmas pudding, warmed by ignited cognac and the requisite hard sauce melting over the top – a spectacular fiery finish to a grand dinner. By the way, the plums in plum pudding are actually dried prunes, but if you happen to freeze a few dozen fresh plums in the summer, you may use them in the pudding to make it more Dickensian.

Makes: 8 small (225 g/8 ounce) or 4 large (450 g/16 ounce) puddings

150 g/1 cup golden raisins

150 g/1 cup currants

150 g/1 cup chopped dried apricots

150 g/1 cup chopped dried seedless prunes

150 g/1 cup chopped dried figs or dates, or a mixture of both

1 large tart apple, chopped fine

240 ml/1 cup plum purée (see Note)

100 g/2 cups fine breadcrumbs (from your own good bread, of course!)

170 g/1 cup brown sugar

Zest and juice of 1 orange

Zest and juice of 1 lemon

5 ml/1 teaspoon ground cardamom

In a very large bowl, mix the dried fruits, apple, plum purée, breadcrumbs, sugar, orange and lemon zest, orange and lemon juice, spices, and salt. Toss to mix and add the cognac. Stir until moistened. Cover and leave at room temperature for 24 hours, tossing once or twice.

Butter four 15 cm/6-inch pudding moulds or eight 13 cm/5-inch heatproof 225 g/8-ounce glass dessert bowls. Have ready a large roasting tin or other pot large enough to hold the moulds or bowls snugly. It should have a lid. If not, fashion one from foil.

Add the flour, almonds, suet, and eggs to the fruit mixture, stirring well to distribute the eggs. Spoon the pudding mixture into the moulds, packing it tightly and filling them nearly to the rims. Leave a 1 cm/½-inch space at the top. Cover each one tightly with foil and put the moulds in the larger tin.

Set the roasting tin on the stove and pour enough boiling water into the tin to come halfway up the sides of the moulds or 4 cm/1½ inches up the sides of the larger tin. Cover the tin and return the water to a boil over high heat. Reduce the heat to low and simmer for 1½ to 2 hours. Add more boiling water as necessary to maintain the correct depth, or simply add water, bring it to a boil, and then lower the heat.

Remove the moulds from the larger tin and let the puddings cool. Remove the foil and loosen the puddings by running a sharp knife around the inside of the moulds. Invert the puddings onto a work surface and sprinkle each with the cup of cognac. Wrap tightly in plastic wrap or cheesecloth and then in foil. Refrigerate for at least 1 week and up to 1 year.

5 ml/1 teaspoon ground mace

5 ml/1 teaspoon ground fresh nutmeg

5 ml/1 teaspoon ground ginger

Pinch of salt

Pinch of ground cloves

360 ml/1½ cups cognac

188 g/1½ cups sifted unbleached plain (all-purpose) flour

180 g/1½ cups chopped toasted almonds

225 g/½ pound chopped beef suet or 225 g/1 cup unsalted butter, softened

6 large eggs, beaten

240 ml/1 cup cognac, to sprinkle over baked puddings, plus 60 ml/¼ cup for igniting

Hard sauce (see below)

Preheat the oven to 180°C/350°F/gas 4. Unwrap the puddings and then re-wrap them in foil. Place directly in the oven and heat for about 20 minutes. Unwrap the puddings and arrange on a serving plate.

In a metal ladle, heat the remaining 60 ml/¼ cup of cognac over high heat until it ignites. Pour over the puddings and carry them to the table quickly before the flame goes out. Serve with Hard Sauce.

NOTE: Seed and purée 900 g/2 pounds fresh plums for plum purée, then freeze for your puddings or substitute applesauce.

HARD SAUCE

Makes: About 240 ml/1 cup

260 g/2 cups icing sugar

55 g/¼ cup unsalted butter, softened

30 ml/2 tablespoons cognac or rum

In the bowl of a food processor, combine the sugar, butter, and cognac and process until the consistency of soft icing. Serve with hot plum puddings.

When I was living in the heart of Italy at Christmastime, I had absolutely no reason on earth to make panettone. Many bakeries offered fresh ones and commercial brands hung from the rafters like brightly coloured Chinese lanterns or were stacked in sweet pyramids in the beautifully decorated windows of food shops. But back home, full of nostalgia for my Roman Christmas – musicians from the Abruzzo with their bagpipes made of sheepskins, the smoky smells of roasting chestnuts on every corner, children bundled up as round as soccer balls, warm, perfect espresso restretto (1 cm/½ inch of espresso, often “corrected” with a splash of grappa!) on chilly late afternoons of shopping and people watching – I cheered myself up by making my own.

Homemade panettone is unequivocally on another level from commercial bread and must be made with lots of good butter and fresh eggs. It helps too, if you make your own candied zest, but if you cannot, use fresh grated orange and lemon zest along with raisins plumped for a few minutes or overnight in rum or cognac – and toss in toasted almonds. Some bakeries sprinkle roasted pine nuts on the top of the breads before baking. I sometimes ice the panettone with the same pink sugar icing I use for Russian Easter Bread, but panettone is good as is and needs no adornments. For the correct panettone shape, I like to use empty coffee cans brushed with olive oil, although these breads rarely stick because of the high butter content. For this recipe, you will need two 1 kg/36-ounce or four 340 or 400 g/12-or 14-ounce coffee cans.

Makes: 4 small or 2 large panettone

Sponge:

125 g/1 cup unbleached plain (all-purpose) flour

120 ml/½ cup lukewarm water (30-35°C/85-95°F)

30 ml/2 tablespoons active dry yeast

5 ml/1 teaspoon sugar

TO MAKE THE SPONGE: Thirty minutes before mixing the dough, stir together the flour, milk, yeast, and sugar in a small glass bowl. Cover and set aside.

TO MAKE THE PANETTONE: In another small bowl, soak the raisins in the cognac or rum. In another bowl, beat the egg whites until they hold soft peaks. Take out 30 ml/2 tablespoons to brush the tops of the panettone.

In a large bowl, using an electric mixer, cream the butter and sugar until fluffy. Add the eggs and egg yolks, one at a time, and beat well. Add the orange and lemon zest and vanilla.

Sift the flour with the salt and add to the batter. Mix on low speed, gradually adding the sponge until incorporated. Add the raisins and their liquid, and continue to beat on low speed for a minute or so. Add half the almonds and beat until incorporated. The dough should not be too firm, but should look buttery and a little rough and ragged. Remove the bowl from the mixer and fold in the beaten egg whites.

Turn the dough out onto a floured surface and knead for 3 minutes, pushing the dough away from you with the heels of your hands folding it in half over on itself and repeating the motion. The dough will become smooth and shiny very quickly. Transfer the dough to an oiled bowl, cover, and let it rise in a warm place until doubled in volume, about 2 hours.

Panettone:

150 g/1 cup golden raisins or Suzanne’s Roasted Grapes (page 111)

60 ml/¼ cup cognac or rum

2 large eggs, separated

225 g/1 cup unsalted butter, softened

300 g/1½ cups sugar

4 large eggs

15 ml/1 tablespoon grated orange zest

15 ml/1 tablespoon grated lemon zest

5 ml/1 teaspoon pure vanilla extract

About 565 g/4½ cups unbleached plain (all-purpose) flour

5 ml/1 teaspoon salt

125 g/1 cup toasted, chopped almonds

75 g/½ cup mixed Candied Orange and Lemon Peel (page 132)

35 g/¼ cup toasted pine nuts, for garnish, optional

Turn the dough out on a work surface and flatten into a rectangle. Spread the remaining almonds and the candied zest across the dough lengthwise. Starting at the short end, roll the dough over the nuts and candied zest. As you roll the dough, knead the nuts and candied zest into it to distribute equally. This takes about 2 minutes with a steady pressing motion of the heels of the hands. Let the dough rest 15 minutes.

TO SHAPE THE PANETTONE: Thoroughly butter two 900 g/36-ounce or four 340 or 400 g/12- or 14-ounce coffee cans. Divide the dough into 2 or 4 pieces, depending on the number of coffee cans. Shape each piece into a ball and place the balls in the cans (the dough should fill cans about half full). With a sharp knife or kitchen shears, cut an x in the top of each about 1 cm/½ inch deep. Brush each with the egg whites. Decorate the tops with the pine nuts, pressing them into the dough. Cover and let the loaves rise until doubled in volume, or about 1 hour. Due to the sugar, the dough may be active at this point and rise quickly, so you may not need a full hour’s rising but a generous rise makes a light panettone.

TO BAKE THE PANETTONE: Preheat the oven to 200°C/400°F/gas 6. Uncover the loaves, place in the oven and reduce the oven temperature to 180°C/350°F/gas 4. Bake for 40 minutes for large coffee cans, 25 to 35 minutes for the smaller cans. Cool in the pans for 15 minutes. Carefully remove the loaves from the cans and cool completely on wire racks. Serve toasted on Christmas day or during holidays with vin Santo. I like mine sliced horizonitallly into rounds and toasted.

NOTE: To toast the almonds, spread them on a baking sheet, spritz with a little water, sprinkle with salt, and toast in a 180°C/350°F/gas 4 oven for about 15 minutes, stirring once or twice. Set aside to cool.

Nuts and fruit may be added to dough during mixing if you have a mixer strong enough to incorporate them, but the first rise may take a little longer because of the weight of the dough.

Candied peel, the outer peel of citrus fruits, made at home is far superior to the peel found in little plastic containers in markets at holiday time. If you can find them without preservatives or the odd flavours that sometimes surface in the commercial peel, use them, but I believe you will always taste the difference in your bread. I experimented by ordering very expensive candied peels from France. I took one sniff and tossed them all into the waste bin! This is not to say good peels do not exist somewhere in the world, but I haven’t found them. You always can count on your own taste best. Tangerine peel works very well, also.

Makes: About 150 g/1 cup

150 g/1 cup slivered or chopped assorted lemon, orange or tangerine peel

200 g/1 cup sugar

60 ml/¼ cup water

Place the peel in a heavy pot and pour enough boiling water over it to cover. Reduce the heat to medium-low and simmer for about 15 minutes or until the peel is transparent and tender. Drain well.

Add the sugar and water and boil until syrupy, about 3 to 4 minutes.

Spread the peel out on a smooth, oiled surface in one layer to cool until crystallized. Store in an airtight jar in the refrigerator or freeze. This will last indefinitely.

RUSSIAN KULICH WITH PASHKA

When my Russian friends at Berkeley discovered that I could make kulich and pashka for Russian Easter, they all showed up at our yearly party, invited or not. I have made this for years, although in my family we are all Czechs with no Russian blood that I know of. I think a brief stay with a Russian nanny, Tolstoy and especially Dr. Zhivago had more of an influence on my cooking than I realized. There is something about the fur hats, sleds and mustached men dancing wildly in black boots that inspired me at an early age to research this amazing bread. I prefer it to the Italian Colombo (dove-shaped bread) for Easter, which is so similar to panettone. Kulich is easier to make in many ways and has the lovely flavours of saffron and cognac to go with the astonishingly rich cheese pashka, which is traditionally served with it. Don’t forget a shot of icey vodka, for the Czar.

Makes: 1 large or 2 small loaves

Sponge:

15 ml/1 tablespoon active dry yeast

TO MAKE THE SPONGE: In a large bowl or the bowl of an electric mixer, stir the yeast with the water until dissolved. Add the milk, sugar, and salt. Stir in the flour and mix well. Cover and let rise for 1 hour until light and foamy.

60 ml/¼ cup lukewarm water (30-35°C/85-95°F)

480 ml/2 cups lukewarm milk (30-35°C/85-95°F)

100 g/½ cup sugar

5 ml/1 teaspoon salt

130 g/1 cup bread flour, sifted

Kulich:

5 large eggs, separated

325 g/1½ cups sugar

5 ml/1 teaspoon pure vanilla extract

845 g/6 ½ cups bread flour

225 g/1 cup unsalted butter, melted

75 g/½ cup graham flour

75 g/½ cup raisins

75 g/½ cup apricots, prunes, or figs, chopped fine

150 g/1 cup ground toasted almonds or pecans

30 ml/2 tablespoons Candied Orange or Lemon Peel (page 132)

15 ml/1 tablespoon lemon or orange zest

60 ml/¼ cup cognac

5 ml/1 teaspoon cardamom

½ teaspoon powdered saffron

Pink Sugar Icing (page 134)

Pashka (page 135) (optional)

TO MAKE THE KULICH: Butter two 1 kg/36-ounce or four 340 or 400 g/12- or 14-ounce coffee cans.

In a large bowl, whisk the egg yolks, sugar, and vanilla until smooth. Add to the sponge and stir or mix on low speed to incorporate. Add 390 g/3 cups of the bread flour, 100 g/½ cup of the butter, and the graham flour and mix just until blended. Add the remaining 455 g/3½ cups of the bread flour and the remaining 100 g/½ cup of the butter and mix well. Add the raisins, apricots, almonds, cognac, candied peel, peel, cardamom, and saffron and mix or stir the dough until it pulls away from the sides of the bowl and is shiny and elastic.

In a separate bowl, beat the egg whites until they hold soft peaks. Carefully fold into the dough. Scrape the dough into the coffee cans, filling each halfway. Set aside until doubled in volume, about 1 hour.

TO BAKE THE KULICH: Preheat the oven to 180°C/350°F/gas 4. Bake for 45 minutes to 1 hour, depending on the size of the cans. Cool in the cans for 15 minutes. Carefully remove the loaves from the cans and cool completely on wire racks. Ice with Pink Sugar Icing (page 134) or spread with pashka (page 135). My Russian friends slice this horizontally from the top, but I prefer to slice it more conventionally so that everyone gets some of the icing.

Makes: About 150 g/1 cup

260 g/2 cups icing sugar

30 g/2 tablespoons unsalted butter

5 ml/1 teaspoon pure vanilla extract

60 ml/¼ cup cognac

2 drops red food colouring (optional)

In the bowl of a food processor, mix all ingredients, except the food colouring, together to make a creamy icing. Add the food colouring to make the traditional pink icing for kulich.

Although you can serve this without the kulich, simply spreading it on any of your own breads, it is truly magnificent with kulich. It is also especially good on rye or wheat breads or served with the Apricot Focaccia on page 106. As when almost any cheese is made, you need to drain the whey to achieve the correct texture. I find that a plastic flowerpot or even a deep sieve with a flat bottom is perfect for draining pashka. Line the pot or sieve with two layers of damp cheesecloth and then pack in the cheese mixture in it to drain overnight. Sometimes I just gather up the cheesecloth (with cheese in it, of course) and tie it securely to my faucet over the sink to drain. In the morning, when the cheese is now a neat little ball of goodness, you put it into any mould you like, refrigerate it, and then turn it out onto a plate to serve. This recipe cuts calories, yet I find it just as tasty and rich as the Russian version.

Makes: 900 g/2 pounds of cheese

675 g/1½ pounds cottage cheese

200 g/1 cup sugar

240 ml/1 cup cream or whole milk

100 g/½ cup unsalted butter, softened

125 g/½ cup plain yogurt

75 g/½ cup toasted almonds, chopped fine

30 ml/2 tablespoons cream cheese, softened, or mascarpone cheese

3 large egg yolks

¼ cup Candied Orange or Lemon Peel (page 132)

40 g/¼ cup currants or golden raisins

15 ml/1 tablespoon grated lemon zest

5 ml/1 teaspoon pure vanilla extract

Pinch of salt

Icing (confectioners’) sugar, for dusting

Leave the cottage cheese, loosely covered, at room temperature overnight or for 12 hours. In the bowl of a food processor, blend until smooth.

In a large bowl, mix all the ingredients, except the icing (confectioners’) sugar, together, stirring well. Pack the mixture into a double-cheesecloth-lined plastic flowerpot or sieve. Set over a bowl or the sink and let drain overnight at room temperature. Turn the cheese out on a plate and serve, dusted with icing sugar.

These are flat, tortilla-like wheat cakes used to scoop up curry, like an edible spoon. I was taught how to make these breads and many delicious curries by an Indian friend in Berkeley during the 1960s, a time when all the corners of our house, day and night, seemed to be filled with jug bands, folksingers and musicians, travellers, and starving students. Bob Dylan (before fame) came by once in those early days, and I remember trimming his unruly hair and feeding him curry. You have to eat, after all, even when the times they are a changin’.

Makes: 16 pancakes; serves 4 to 6

260 g/2 cups whole-wheat flour

65 g/½ cup unbleached bread flour

100 g/½ cup unsalted butter, melted, plus more for the pan

5 ml/1 teaspoon salt

240 ml/1 cup plain yogurt

In a mixing bowl, combine the whole-wheat and bread flours, 50 g/¼ cup of the butter, and salt and rub through your fingers until crumbly. This may also be done with a few pulses in the food processor. Add enough yogurt to make a fairly firm but still malleable dough, not too dry but not sticky. Stir for about 2 minutes to smooth it out. Cover and let rest for 30 minutes. It will be elastic and shiny when ready.

Take pinches of the dough and roll them into 4 cm/1½-inch diameter balls in your palms to make 32 balls. Dip each into the remaining 50 g/¼ cup of butter, flatten it slightly, and set aside. When you have used all the dough, stack in pairs, placing one ball on top of another and flattening it slightly, (layering causes them to bubble) to make 16 pieces of dough, and, on a marble slab or floured board, roll each pair out into a very thin circle, just less than 3 mm/⅛ of an inch thick.

Heat a frying pan or griddle on medium heat and add about a teaspoon of melted butter. When it is bubbling, carefully pick up the chappati, as if you were lifting a delicate fabric, and lay it in the frying pan. Cook for about 1 minute and as each circle bubbles and browns, turn it over and brown the other side for another minute or less; it should not quite reach the point of crispness, just turn a light brown. The chappati must remain supple, like flour tortillas. Stack the chappati, one on top of the other and keep warm, covered with foil, in a very low oven until serving.

NOTE: These may be frozen with great success. This recipe is enough for 4 to 6 people, depending on how many they eat before the curry is served. When you are feeding the masses, you will need 1.25kg/2½ pounds of whole-wheat and ½ kg/1 pound of white flour to make 100 chappati.

(African Spiced Bread)

I am, along with being a shoe fanatic, a basket nut. I buy baskets of all kinds, such as Japanese rice-washing baskets or Chinese fishing baskets, with no purpose other than my illusion that I might just find myself fishing in China when I get some time off. One of my best frivolous acquisitions is a beautiful round African bread basket designed to house ye-wolo (as I found out from the late Hamsa el Din, who was an amazing musician from Nubia). The basket is coloured with vegetable dyes and fitted with great leather loops from which to hang it on the wall. This basket was inspiration for what grew to be my African period – four months of research and cooking with marvellous berberé, a spiced paste which flavours many Ethiopian foods; nit’r k’ibe, a spiced oil; and the making of the famous ye-wolo spice bread. This bread accompanies savoury doro wat, a chicken stew with red peppers, but you may eat it with practically anything and it will be a success. It is a lively detour from the plain dinner breads we know so well.

Makes: One 30-36 cm/12-14-inch round loaf

480 ml/2 cups lukewarm water (30-35°C/85-95°F)

30 ml/2 tablespoons active dry yeast

520 g/4 cups unbleached bread flour

65 g/½ cup whole-wheat flour

35 g/¼ cup Nit’r K’ibe (page 138)

15 ml/1 tablespoon ground cardamom

15 ml/1 tablespoon ground coriander seeds

5 ml/1 teaspoon ground black pepper

5 ml/1 teaspoon Berberé (page 139)

Measure the water into a large mixing bowl. Sprinkle the yeast over the water and stir until dissolved. Stir in the bread and wholewheat flours. Add the Nit’r K’ibe, cardamom, coriander, pepper, Berberé, fenugreek, cloves, and cinnamon and stir until the dough is smooth and shiny and pulls away from the sides of the bowl. The dough will be fairly soft. Cover and refrigerate overnight to give the spices time to permeate the dough.

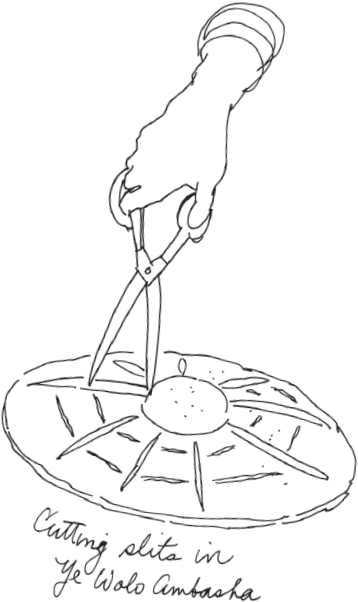

Let the dough come to room temperature. Turn onto an oiled baking sheet and pinch off a small piece of dough about the size of a golf ball. Set aside. Form the remaining dough into a large circle and flatten with your hand until it is about 30 cm/12 inches in diameter. With a very sharp knife, cut slashes in the dough starting at the middle and cutting out as if you were dividing it into wedges about 2.5 cm/1 inch wide at the edges of the bread (see illustration). Press the ball of dough into the centre of the circle. With scissors, snip across the wedges starting at the point and working to the outside to make the traditional design of the Ye-wolo (see illustration). Let rise until doubled in volume, about 45 minutes.

5 ml/1 teaspoon ground fenugreek

Pinch of ground cloves

Pinch of ground cinnamon

20 ml/4 teaspoons olive oil

Preheat the oven to 200°C/400°F/gas 6. Brush bread with olive oil and bake for 15 minutes. Reduce the oven temperature to 180°C/350°F/gas 4. Bake for about 30 minutes longer, or until the bread is nicely browned. Cool on a wire rack.

NIT’R K’IBE

This is great in non-African dishes, too. Try a spoon of it on grilled meat, poultry, or fish. Or toss it with noodles for a very exotic pasta to serve with Southeast Asian foods. You may also use a spoon of it in any plain bread or biscuit recipe to liven it up.

Makes: About 150 g/1 cup

450 g/2 cups unsalted butter

3 cloves garlic, chopped fine

1 small sweet onion or spring onion, chopped fine

15 ml/1 tablespoon fresh grated ginger

5 ml/1 teaspoon turmeric

5 ml/1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

5 ml/1 teaspoon ground cardamom

5 ml/1 teaspoon grated nutmeg

5 ml/1 teaspoon ground fenugreek

Pinch of ground cloves

Pinch of salt

Pinch of black pepper

In a heavy pot, heat the butter until it bubbles. Stir in the rest of the ingredients and let the mixture cook over very low heat until separated, about 30 minutes. Strain through a fine sieve into a glass container, making sure there are no visible butter solids. This will keep, like the Indian clarified butter, ghee, for several weeks in the refrigerator. It may be frozen.

This is hot.

Makes: About 300 ml/1¼ cups

Spices:

120 g/1 cup sweet Hungarian or French paprika

15 ml/1 tablespoon ground hot red peppers or cayenne

5 ml/1 teaspoon ground cardamom

5 ml/1 teaspoon ground coriander seeds

5 ml/1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

5 ml/1 teaspoon grated fresh nutmeg

5 ml/1 teaspoon ground fenugreek

5 ml/1 teaspoon powdered asafoetida (see Note)

Pinch of ground cloves

Pinch of ground black pepper

15 ml/1 tablespoon olive oil

1 small onion, chopped fine

2 cloves garlic, chopped fine

5 ml/1 teaspoon salt

5 ml/1 teaspoon grated fresh ginger

Dash of red wine vinegar

240 ml/1 cup water

In a heavy pan, toast the spices over low heat for about 3 minutes, stirring constantly so they will not burn, until fragrant. Remove from the pan and set aside.

In the same pan, heat the olive oil over medium-high heat. Sauté the onion and garlic until golden. Add the spices, salt, ginger, vinegar, and water and cook for about 10 minutes over low heat, stirring well.

Transfer to a blender or food processor and purée. Store in a glass jar with a tight lid. Pour a little olive oil over the top of the paste to preserve it for up to 3 months.

NOTE: Asafoetida is sold in Indian food stores in lump or powdered form. Use it sparingly.

The scent of truffles always takes me back to Citta di Castelo where, years ago when searching for the Alberto Burri museum, we wandered into an amazing Sagra di Tartuffi (truffle festival) instead. A handsome young man with the brown-stained hands of a truffle hunter and a certain unmistakable aroma emanating from his stylish Italian sweater watched with interest as we sighed over the tables and tables of truffles brought to auction from the countryside. He introduced himself as owner of Il Bersaglio, a local restaurant offering a dégustation of ten truffle courses, of which one was a golden homemade pasta made with numerous egg yolks and unequalled in the area. We trotted along behind him to his ristorante, like truffle pigs (or dogs, now used because they don’t eat the loot) in hot pursuit. Over the next two hours, we managed to lay waste to all ten courses while he sat with us, pouring both wine and his philosophy of life, which included truffle eating as part of everyday consumption. If one has the means to do it, that is.

“I have not needed more than four hours sleep since I became a truffle hunter,” he said. “The truffle is my life, I have no time for women or family. I live only to hunt truffles and run my restaurant and need nothing else and have the strength of two, no, three men!” Needless to say, truffles can be very seductive, but I am still wondering how many women in Cittá de Castello wish they were benefitting from this remarkable stamina….

You’ll find truffle oil in the olive oil sections of larger supermarkets or in delis. Another way to have a nice stash of truffle oil is to buy a very small white truffle during the truffle season, October through December, and put it in a bottle of good olive oil; wait about 24 hours before using it. The oil, well-stoppered, will last for months and cost less than the commercial kinds. I love truffle oil on this bread or bruschette, but when there are fresh truffles available for pasta, use only the tubers, as truffle oil is not needed and can alter the taste of your dish.

Makes: 20-24 rolls

180 ml/¾ cup lukewarm water (30-35°C/85-95°F)

1 sachet active dry yeast

280 g/2¼ cups unbleached plain (all-purpose) flour

5 ml/1 teaspoon sugar

5 ml/1 teaspoon salt

1 large egg, beaten

TO MAKE THE DOUGH: Measure the water into the bowl of an electric mixer. Sprinkle the yeast over the water and stir until dissolved. Add 125 g/1 cup of the flour, sugar, and salt and beat on low speed until smooth. Add the egg, butter, and remaining 160 g/1¼ cups of flour and beat on low speed until well blended and shiny.

SAME DAY METHOD: Cover the bowl and let the dough rise in a warm place until doubled in volume, 30 to 45 minutes. Stir down the dough.

OVERNIGHT METHOD: Cover the bowl and refrigerate overnight. Remove the dough from the refrigerator 30 minutes before shaping. Let stand in a warm place until doubled in volume. Stir down the dough.

TO SHAPE ROLLS: Grease two 23 cm/9-inch round cake tin/baking pans with oil. Drop the dough by generous spoonfuls into mounds about 2.5 cm/1 inch apart into the pans, or shape into little balls, arrange in the pans, and press down slightly to flatten each one. Cover and let rise until doubled in volume, 30 to 40 minutes. Brush with 5 ml/1 teaspoon of the truffle oil.

TO BAKE ROLLS: Preheat the oven to 200°C/400°F/gas 6. Bake for 17 to 20 minutes, or until golden brown. Remove from the oven and brush with remaining 5 ml/1 teaspoon of truffle oil. Serve warm.

NOTE: If you just happen to have extra white truffles lying around, chop one and add it to the dough, or keep them all for yourself, shaved over a nice bowl of fresh fettucine!

I cannot resist the breadsticks that almost every trattoria in Rome serves along with the bread. Bread-sticks are irresistible to children, and when my brother and I were taken out to restaurants, we inevitably either “smoked” them or poked each other mercilessly until they broke. Tiring of this, we began fencing or trying to beat one another over the head with them, managing to make a sizable mess before my mother threatened to have us arrested or forego dessert, or, in any case, the shrimp cocktail. I was never a sweets eater even then, but give me a bowl of boiled Gulf shrimp, some remoulade sauce and a few breadsticks and I would even behave myself.

In keeping with this custom, the eleven-year-old guests at my stepson’s birthday party years ago on an open restaurant terrazza (thank heaven) in Rome had a breadstick-eating contest, followed by a collective laughing fit, which resulted in a shower of spewed crumbs and bemused looks from adjacent tables.

I have made straight breadsticks, rolled ones, pulled ones, bent ones, seeded ones, and sugared ones, and they all are delicious and crunchy, as seductive now as they were when I was eight years old. Of course, I would never do such silly things with them as I did then…except when I need a cigar for my Groucho Marx impersonation.

Makes: 20-24 thin breadsticks

Biga:

5 ml/1 teaspoon active dry yeast

120 ml/½ cup lukewarm water (30-35°C/85-95°F)

65 g/½ cup unbleached plain (all-purpose) flour

Dough:

60 ml/¼ cup olive oil or melted unsalted butter

4 tablespoons fresh rosemary leaves, chopped fine

5 ml/1 teaspoon active dry yeast dissolved in 15 ml/1 tablespoon of water

TO MAKE THE BIGA: In a glass bowl, mix the yeast with the water and stir well. Add the flour to the yeast mixture, stirring well to aerate the mixture and form a wet dough. Cover tightly with plastic wrap and let ferment overnight at room temperature. In the morning, it will be bubbly and fragrant.

TO MAKE THE DOUGH: In a small saucepan, heat the olive oil over medium heat and sauté the rosemary leaves until soft, about 3 minutes. Set aside to cool.

In the bowl of a food processor combine the yeast, flour, milk, salt, pepper, and sugar if using, and pulse until moistened, about 10 seconds. Add the rosemary and oil. Add the biga and process until the dough pulls away from the sides of the bowl. Do not overmix.

Oil your hands and remove the dough from the processor. Form the dough into a nice shiny ball and place in an oiled bowl. Cover and let rise until doubled in volume, about 1 hour. Push down the dough and let it rest for 15 minutes.

Flatten the dough into a rectangle about 10 cm/4 inches wide and 1 cm/½ inch thick. With a sharp knife, cut strips of dough 2.5 cm/1 inch wide. Roll each strip lengthwise, as if you were rolling clay, pulling it slightly to lengthen the dough into a long, thin, even shape like a long worm. Or, if you are fairly skilled at baking, grasp each end of the long piece of dough and gently flap it against the counter, lengthening the breadstick as you flap. Make the strips any width you like, fat or thin, but they must be all the same width to bake evenly together.

125 g/1 cup unbleached plain (all-purpose) flour

60 ml/¼ cup warm milk

5 ml/1 teaspoon salt

10 ml/2 teaspoons ground black pepper

5 ml/1 teaspoon sugar, optional

Coarse salt, for sprinkling

TO BAKE BREADSTICKS: Preheat the oven to 200°C/400°F/gas 6.

Carefully lift each end of the breadsticks and place them 1.5 cm/1 inch apart lengthwise on an ungreased baking sheet. With a spray bottle, mist the breadsticks, sprinkle with coarse salt, and let rise while the oven heats. Bake for 10 to 12 minutes or until golden. Use as drumsticks, weapons, table ornaments, or cigars, or simply bite and enjoy.

*A top Italian truffle oil purveyor.