Appendix 1 Committing to an Operating Model to Build an Operational Backbone

In chapter 3, we introduced the operational backbone as the building block companies assemble as they digitize their business processes to create a foundation for efficient and reliable operations. Of the five building blocks, most companies characterize the operational backbone as the biggest obstacle to their digital transformation.1 That is why this appendix describes a key prerequisite for effectively building an operational backbone: the commitment to an operating model.2

What Is an Operating Model?

An operating model is the desired level of business process integration and business process standardization for delivering goods and services to customers.3 Rather than a current state, the operating model describes the target state of how much your business processes should be standardized and integrated.

A standardized business process is performed the same way, no matter where and by whom it is executed. For example, McDonald’s is well known for its standardization of operational processes around the globe. Similarly, when CEMEX grew internationally, leaders defined a set of processes, ranging from procurement and finance to logistics and HR, called the “CEMEX Way.” Every country organization adopted this enterprise-wide standard way of working.

In contrast, integration is about sharing data among different processes, because they are interdependent: what happens in one business process depends on what happened in another business process. When one of the authors of this book moved to the US, American Express offered him a credit card even though he had not established a credit history in the US. Since the author had previously owned an American Express credit card in the Netherlands, the company’s decision was based on data generated by his past transactions in that country. Obviously, American Express had integrated data from some business processes across the globe.

Four operating models

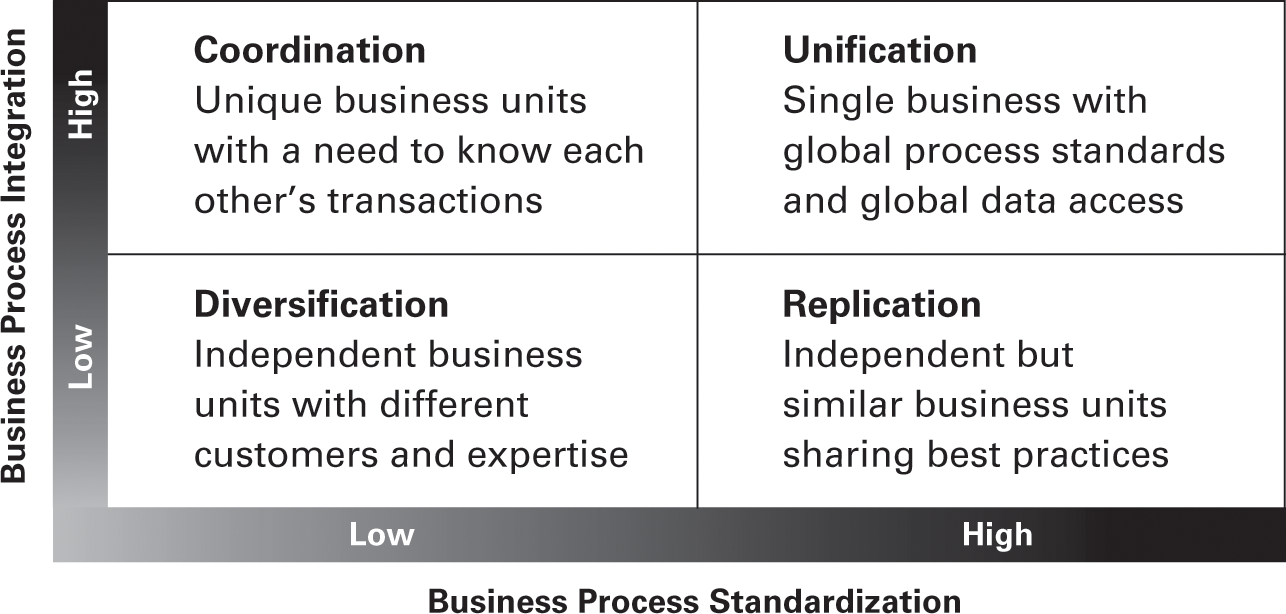

Recognizing business process standardization and integration as two distinct dimensions, companies can choose from among four different operating models (see figure A1.1):

- Replication, characterized by a high desire for standardization, but little need for integration

- Coordination, with the opposite requirements: a high need for integration, but not so much for standardization

- Unification, with a high need for both standardization and integration

- Diversification, characterized by low needs for both standardization and integration

The following examples illustrate the different needs addressed by each operating model.

ING Direct Spain was the first of the ING Direct fleet of country banks to introduce a checking account.4 When other ING country banks decided to do the same, they first went to Spain to understand how that bank was selling and operating the new product (e.g., how it on-boarded customers) in order to copy their processes. In this way, the countries could learn from each other and share best practices. But if you were a customer of ING Direct Spain and ING Direct Germany, the two banks wouldn’t know that because the two banks did not share data. Neither bank’s processes would be affected by the fact that you were an ING customer twice over. In other words, ING Direct was following a replication operating model: highly standardized processes across countries, but no integration across banks.

When USAA introduced integrated solutions such as Auto-Circle, it needed to share data among different processes.5 As we described in chapter 1, Auto-Circle combined various financial products like automobile insurance, loans, and buying services into a seamless experience around buying a car. Hence, USAA needed to exchange data among the processes in its different lines of business, such as insurance and banking. But USAA did not require standardizing processes across these lines of business, partly because of different regulatory requirements and partly because of different product features. USAA was following a coordination operating model.

When DHL Express set out to turn around its international shipping business in the US, it decided it needed both business process integration and standardization.6 For example, it wanted its global customers to be able to track a shipment from the US to Brazil even when calling a customer service center in Singapore. That required data sharing. To ensure the integrity of the data and the predictability of the process, DHL also wanted to adopt in the US the standardized logistics processes like inbound and outbound package handling that had been adopted in other countries. Hence, DHL Express followed a unification operating model.

Portfolio companies like Berkshire Hathaway don’t need integration among the different companies in their portfolio (in fact, integration would hinder any attempts to sell a company quickly). Such companies also have little need to standardize their core business processes. This is why they pursue a diversification operating model.

How to Choose among Operating Models

Each operating model is a valid choice; no model is superior. Instead, with each operating model, companies can expect certain benefits, while forgoing others. Through standardization, replication promises consistency that ensures the same transaction quality across different countries or units. It facilitates efficiencies at the cost of differentiation. It also offers scale benefits: the same processes (and the systems supporting them) are reused multiple times. A related benefit is that employees can easily transfer to different company locations.

Because it is concerned with standardization and not integration, the replication model does not offer a single cross-unit view of, say, customers. That is a key benefit of the coordination operating model. Companies adopt a coordination operating model so they can serve customers across business silos while enabling differentiation of products and services across different parts of the company. Because they do not standardize processes, however, companies choosing the coordination operating model find it can be costly to maintain. It enables customer intimacy but sacrifices efficiency.

Unification, of course, combines the best of replication and coordination: efficiency and enterprise-wide view of key data. Unification, however, sacrifices local responsiveness and the ability to customize for individual segments, lines of business, or geographies. For companies selling commodity products, unification facilitates operational efficiency. But if a company wants to avoid commoditization, the unification operating model is a bad choice.

The diversification operating model maximizes local innovation. It enables business units to grow independently. With fewer constraints, business units in a company adopting a diversification operating model can experiment locally and quickly implement innovations that respond to customer needs. Although some companies adopting a diversification operating model introduce enterprise shared services to generate economies of scale, these systems and processes are hard to adopt because local business leaders are accustomed to autonomy. Some shared services around non-distinctive processes make business sense, but they can be difficult to implement.

Readers should note that complex companies have to make operating model decisions on multiple levels. For example, a company’s operating model on the corporate level (e.g., the degree of integration and standardization across various business units) can be different from its operating models at the business unit level (e.g., the degree of integration and standardization across regions within a given business unit).

How Does an Operating Model Relate to Building an Operational Backbone?

Building an operational backbone demands a commitment to an operating model. If a company does not choose an operating model, every IT investment cycle will find the company pursuing immediate concerns rather than building long-term capabilities. IT and change management decisions will lack coherence. Thus, companies that want local responsiveness but insist on implementing global ERPs with standardized processes will find the outcomes frustrating. Meanwhile, companies attempting to create a single view of customers but adopting a diversification model will never get that single view.

You need not adopt a pure operating model (for example, you can decide that customer data must be integrated but product data need not be), but you must commit to the operating model you choose. How do you plan to profit and grow? Do you need local responsiveness more than scale benefits? Do you need to have an integrated view of the customer? Do you need to ensure consistency across your businesses?

Choosing an operating model helps companies focus their systems and process change investments on the most essential aspects of their operational backbone. For example, for the replication model, enterprise systems like ERPs and product life cycle management systems can provide the systems support for standardized processes. Because replication doesn’t require data sharing, these enterprise systems can be defined and implemented at the business unit level.

Unification, in contrast, requires that such systems be adopted globally. The coordination model requires shared access to central data. Companies often adopt CRMs to standardize their data capture and user interfaces. Companies with diversification models implement systems best suited to the individual businesses (except where the company attempts to drive efficiencies by standardizing non-distinctive shared services).

The value of the operating model is that it defines the default choice for the questions of standardization and integration. For example, in a replication model, when facing the decision of whether to follow a standard process or leave room for local responsiveness, the default answer is to follow the standard, but for a given process, there may be good reasons to deviate. Without this agreed-upon default decision, every IT investment decision requires an organizational justification. A company with a default operating model need only debate requests for exceptions.

Some companies find themselves trying to deliver integrated solutions to customers when their business units are silos hoarding their own, inconsistent data, and supporting many variations of a business process. Conversely, other companies are wasting money trying to implement enterprise systems when they have designed governance and incentives for local innovation. A commitment to an operating model provides consistency between investments and capabilities.

Deciding on an operating model is a strategic commitment that cannot be changed easily. Switching to another operating model (or establishing one in the first place) involves changing how people are working and how systems are interacting. The operating model affects roles, incentive systems, and skills. For example, when Royal Philips standardized global business processes, leaders introduced executive business process owners (at the level of the executive committee) to enforce these standards. The IT unit stopped asking business unit leaders for their requirements and interacted mostly with business process owners, who were responsible for aggregating requirements from different units.7 Philips did business differently after changing the company’s operating model. This is why digitizing your processes with an operational backbone is a business transformation. This is also why it’s hard.

Committing to an operating model is the first step in building your operational backbone. We anticipate it will also help companies define how they approach their digital platform building block. Specifically, a diversified company will build multiple digital platforms—one for each autonomous business, while a company with a unification operating model will surely want just one. Replication and coordination companies likely have choices on how to design their digital platforms, particularly if they have a robust operational backbone. Figure A1.1 can help you start the discussion on what operating model will work best for you.

Notes