7 Developing a Roadmap for Your Digital Transformation

As you may recall, when Dorothy wanted to go back to Kansas, she had to seek out the Wizard of Oz. It wasn’t easy to find the wizard, but at least the path was clear. Follow the yellow brick road.

For established companies that want to go digital, the message is clear: develop five building blocks. Unfortunately, the path is much more cluttered than the yellow brick road. Established companies are sustaining—and improving—their existing businesses as they try to develop digital capabilities. It’s not possible to do everything at once. This chapter examines alternative journeys for becoming a digital business.

Assembling the Building Blocks

The digital building blocks reviewed in the last five chapters are organizational capabilities that, according to our research, companies must develop to succeed at digital. To summarize, we have found that a well-designed digital organization has each of the following five capabilities:

- Shared insights about what digital solutions the company can develop that customers will pay for (this building block constantly expands knowledge of the intersection between what the company can do with digital technologies and what customers desire).

- An operational backbone that captures the company’s requirements for integration and standardization of core operational processes (this building block enforces reliability in the execution of foundational processes and integrity of company data).

- A digital platform of reusable digital components making up digital offerings (this building block provides access to repositories of business, data, and infrastructure components).

- An accountability framework that allocates decision making rights to ensure both autonomy and alignment (this building block defines roles, decision rights, and processes to support speed and alignment in development and use of the digital platform).

- An external developer platform that exposes digital components to external partners (this building block provides the technology, processes, and roles enabling digital partner relationships).

Figure 7.1 shows our depiction of the five building blocks for a digital transformation.

The digital building blocks (as introduced in chapter 1)

Our research confirms that, statistically, the building blocks are five unique, albeit interrelated, organizational assets that contribute individually and in combination to business success.1 Each building block introduces changes to a company’s people, processes, and technology. Consequently, not only is the digital journey long; the series of initiatives to develop any given building block is a journey in itself.

A well-developed set of building blocks is related to greater innovativeness of digital offerings and more revenues, profits, and customer satisfaction from those digital offerings.2

In a perfect world, companies would be able to develop their building blocks simultaneously—with the possible exception of the external developer platform. Simultaneous development would allow companies to take advantage of the interdependencies among the building blocks. Improving one would improve the others, which would enhance overall benefits.

We have observed, however, that large companies cannot simultaneously address all the building blocks when they kick off a digital transformation. There are too many moving pieces demanding too much organizational change. Thus, leaders must make strategic decisions as to which building block(s) they will focus on at any given time. A transformation roadmap can help sequence development of the building blocks.

Our research suggests that there is no single roadmap that will be optimal for all companies. Companies embark on their digital transformations with different competencies and cultures, and they aim for distinctive futures. What companies have in common is the need to develop the capabilities captured in the five building blocks. Where they differ is in the speed and sequencing of their digital journeys.

For example, leadership at CarMax decided to “spark” a transformation by implementing a new accountability framework that dramatically redesigned work for the subset of people focused on digital offerings. Soon thereafter, CarMax started developing a digital platform. Years ago, USAA started to develop customer insights so that it could provide integrated solutions for members of the US military. Then it redesigned accountabilities so people could deliver those solutions. Philips and Schneider spent years fixing up operational backbones to support core business processes and enable digital initiatives. They followed up those efforts by initiating development of a digital platform. Northwestern Mutual bought LearnVest, a start-up with an early digital platform, to propel its digital transformation. It then redesigned accountabilities to ensure it could build and leverage digital components.

Given that these different approaches fit well with the needs of the individual companies, we do not propose one optimal digital journey. Instead, we illustrate the different journeys of four companies to give you some ideas about how you can map your company’s journey. These companies’ digital journeys should help you identify opportunities as they unfold and address the biggest impediments to seizing those opportunities. The most successful companies are pursuing a focused set of capability-building initiatives so that they make steady progress without risking overwhelming organizational changes. The important thing is to get started on the five building blocks. Principal Financial in Chile provides an example of how one company is doing exactly that.

How Principal International Chile Started Its Digital Journey

With its 2,000 employees, Principal International Chile (PI Chile), a subsidiary of Principal Financial Group, focuses on helping its about 800,000 customers become financially ready for retirement.3 It does so by providing mandatory savings plans, mutual funds for additional voluntary savings, and insurance annuities for retirees.

Chile’s pension system requires employees to contribute 10% of their salary to mandatory savings plans. That, however, is insufficient for most people to match their pre-retirement lifestyle upon retirement. PI Chile is committed to using digital offerings to help improve retiree financial security in Chile.

PI Chile has been monitoring digital startups, knowing that customers want easily accessible, simple advice. But its early attempts at becoming digital focused on technology investments. PI Chile Country Head Pedro Atria described the limited impact of this strategy:

So, we started doing some things here, some things there. We risked having the “shiny toys” syndrome: AI, cloud, mobile, augmented reality. About one year ago, we asked, “Of all these amazing things in the digital world, what would really add value to our customers?”

In September 2017, senior management took a one-week trip to visit Silicon Valley companies. They found themselves in very different kinds of discussions about digital than expected. “All of our discussions had been about strategy, about the vision, about the value proposition, about customers,” said Atria. “Because digital is strategy, it’s not IT.”

After this trip, senior management formulated a new digital strategy. It became the business strategy of PI Chile, focusing on using digital technologies to help customers achieve financial security.

Preparing for Digital

As PI Chile embarked on its digital transformation, leaders built on the company’s existing operational backbone and the beginnings of a digital platform. The company’s operational backbone included two internally developed core systems providing data and functionality around customers and products. The monolithic design of these systems was not perfectly suited for an increasingly digital company, but they offered reliable support for the company’s operational processes. PI Chile was also digitizing its customer-focused sales processes as it implemented a cloud-based CRM system.

PI Chile’s early digital platform was the foundation for its PrincipalConnect.cl customer portal. The company had contracted with a local startup to build it; the start-up delivered the first version in just two months. PI Chile leaders viewed their operational backbone and digital platform as a good start to building a digital business, but they also saw the need to create what they call “the muscle,” the organizational capabilities required to build digital offerings. As Atria explained,

We didn’t have a digital company. To develop that, we need better data, and we need a different organization, including new talent, different processes, and new, aligned technology. Even our organizational structure … [is] from an analog world, and we need a structure for the digital world.

Following the announcement of its digital strategy in September 2017, leaders mapped out a transformation journey that focused on the development of two digital building blocks: preparing its operational backbone to support digital offerings and initiating changes to accountabilities and how people worked.

Developing an Operational Backbone

To quickly enable the development of digital offerings that needed data and functionality from the operational backbone, PI Chile’s CIO decided to “wrap” core systems in APIs, that is, to develop APIs to act as intermediaries between the operational backbone and digital offerings. This allows digital offerings to access backbone data or functionality without directly accessing the legacy systems, as those might get replaced in the future.

Top management allocated a budget for developing the first APIs. Two employees in a new, central IT unit coordinated the development of APIs. When digital offering teams saw the need for data or functionality from the operational backbone, they contacted the central API team. The API team checked to see if an API already existed, and if it did not, they designed a new, reusable API. As of mid-2018, the API team had developed around 50 APIs.

Developing an Accountability Framework

To experiment with new ways of working, PI Chile established a new Digital Experience Lab (or DXLab) in 2017. After a nimble start with a handful of employees, the lab had grown to 43 employees by mid-2018. According to the DXLab’s director, Daniel Langdon, working there was very different from working elsewhere in PI Chile.

Everything from how you sit, where you sit, how you collaborate, where you collaborate, what your timetables are, what your perks are, what your organizational structure is, what your career is going to be, etc. In all of those dimensions, we are changing radically.

The DXLab was organized into autonomous teams. Each team had at least a product owner with deep understanding of the business problem, a couple of developers, and a designer. Experienced members served as Agile coaches to teams. Every team was also connected to a business sponsor in one of PI Chile’s businesses.

Each team was responsible for an offering (such as PrincipalConnect.cl) or a shared component of those offerings (such as a wellness score component that measured a customer’s retirement readiness). Teams were organized into “domains.” For example, “advice & sales,” “fulfillment,” and “relationships” were domains; “marketing cloud” was a sub-domain of the “relationships” domain, and “financial planning” was a sub-domain of the “advice & sales” domain. The idea was that domains would have little overlap, so that teams could work as independently as possible.

Another huge shift was that teams stayed responsible for their “product” for its entire life cycle. “A product might eventually die,” said Langdon, “but it’s more likely to pivot, and if you completely disband the team, you lose all the knowhow, all the information to do that.”

Teams, which were called “cells,” worked autonomously. Rather than discussing everything with everyone along the hierarchy, teams just made decisions about their “product” themselves. Empowering teams this way located decision making closer to the relevant knowledge. Langdon explained that reliance on empowered teams changed management’s role:

[With hierarchical decision-making] the team first breaks everything down to a few bullet points so that I (as their manager) can make a decision. Then I, the manager without the deep picture, get to ask questions that the team has evaluated for weeks. And I start making suggestions that they have already invented, investigated, evaluated against the alternatives, and discarded! We rehash all of those conversations. The only reason that happens is because there’s no real confidence, and no real delegation of trust. Instead, what we say now is, “this is your domain, this is your playground, and this is what you need to get done.” We just build the right culture, build the right team, enable them, delegate the decision-making, and trust the people. And if they have friction, we resolve that friction! Resolving friction is the way I see my role.

Langdon made clear to his teams that with this increase in autonomy came increased responsibility:

You cannot say, “The business didn’t give us what we wanted.” “The IT people did not respond to us.” “The provider didn’t …” No, no, no. All that is all gone. You’re it.

PI Chile expected to spread the DXLab’s ways of working to other parts of the business. Leaders established a handful of Agile cells in other parts of PI Chile focusing on local innovations. DXLab coaches supported these cells. The number of Agile cells was expected to grow quickly.

Developing Additional Building Blocks

Although management focused first on the operational backbone and accountability framework, PI Chile took some early steps to develop its digital platform and acquire customer insights. Leaders consciously decided against pushing for an external developer platform during this time.

As noted, PI Chile had bought an early digital platform supporting PrincipalConnect.cl, which the DXLab was extending. The company was also building a new mobile app and various shared digital business components (like the aforementioned wellness score component). At the same time, the DXLab was creating various reusable technical components (like one enabling single sign-on) to its digital platform.

Meanwhile, the DXLab was conducting experiments to gain customer insights. Becoming more customer-centric was considered essential, as the company believed that customer insight was more difficult to copy than products. The cells worked in an iterative and incremental way to learn quickly what worked and what did not. Of these experiments, PI Chile’s Chief Digital Officer Juan Manuel Vega said,

We’re taking a lot of risks. The DXLab is a space where we can actually fail. We’re trying different things that we know are going to fail. Failing was not an option eighteen months ago. Today, we are failing fast, and fortunately we’re failing cheap.

When developing new offerings, DXLab teams sought to learn from customers. For example, when building the first version of the mobile app, customers were asked to use a prototype while being recorded on the smartphone they used. That allowed the team to observe customer reactions. As part of transferring what they were learning about customers, and to get further internal feedback, every Friday the DXLab showcased one of the offerings it was working on.

Looking Ahead

PI Chile leaders are keenly aware that a successful digital transformation requires experimentation. Its transformation roadmap is designed to facilitate that experimentation, according to Roberto Walker, president of Principal Latin America:

We would like to end up with a digital company end to end. We know also that we are not going to get it right the very first time … because we know reasonably well what we would like to achieve, but we don’t know exactly what it will be like, or what is the best … or fastest … way to get there.

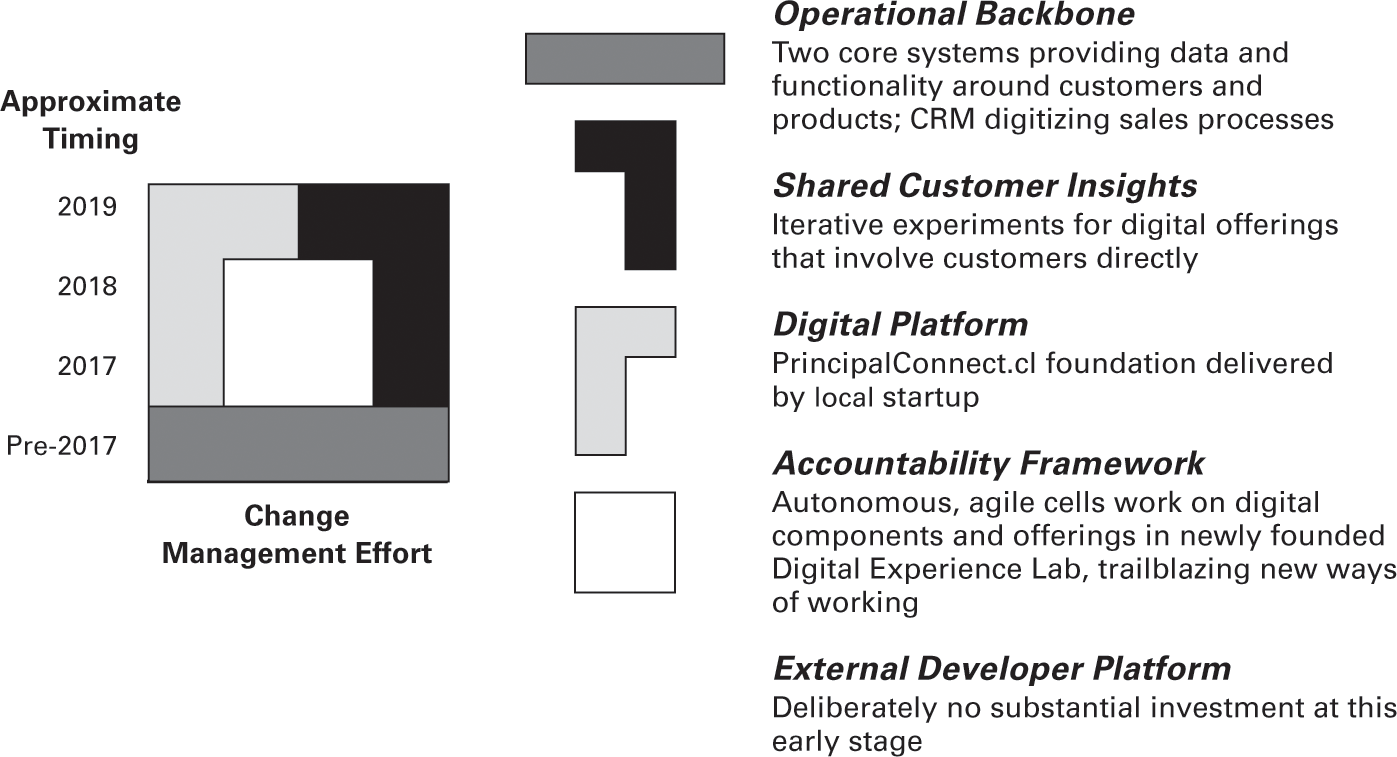

In its first year, PI Chile made significant progress on its digital transformation. Figure 7.2 illustrates the authors’ interpretation of PI Chile’s journey. We reflect the initial investment in each building block with a shape that reflects the period of time the company initially focused on establishing that building block. As shown, the company first attacked the operational backbone by wrapping key systems in APIs for digital access. The company’s accountability framework is the centerpiece of its transformation. By clarifying ownership for customer insights, digital components, and wrapping of operational backbone data, PI Chile is allocating ownership for tasks that will support development of the other building blocks. The DXLab provides a safe environment for PI Chile to develop its building blocks: new accountabilities and ways of working, development of a digital platform, and accumulation of customer insights. Starting with the accountability framework is allowing PI Chile to accelerate its digital transformation. Meanwhile, not diverting resources to an external developer platform helps the company focus on its other building blocks.

PI Chile’s development of digital building blocks (author interpretation)

Alternative Roadmaps for Building Digital Assets

The PI Chile case highlights both the benefits and the challenges presented by the interdependencies of the building blocks. It is not possible to quickly instill a digital culture and develop digital capabilities in a company that was not born digital. Instead, established companies must accumulate digital capabilities over time.

Part of the challenge in developing any given building block is unlearning old habits and learning new ones. We have found that companies succeed with a building block when they devote significant resources to instituting the new habits required by that building block. For example, companies adopt a test-and-learn approach as they experiment with digital offerings to build customer insights. They invest in adopting standardized processes to build an operational backbone. The digital platform requires companies to create and reuse infrastructure, business, and data components as they build a digital platform. Developing an accountability framework involves assigning empowered and aligned teams to own responsibility for components and offerings. The external developer platform requires developing partnerships that drive additional value from the company’s digital platform. Unlearning old habits and learning new habits demands an organizational commitment. That is why it’s not possible to develop all building blocks simultaneously.

Successful companies focus initially on developing one or two building blocks. Leaders invest resources to lead the change that will embed a new digital capability. The investment pays off by gradually making the company more agile and enabling progress in the design and delivery of digital offerings. However, progress on any given building block will be thwarted eventually if there is a lack of investment in other building blocks. At some point, leaders need to turn their attention to a different building block to grow the company’s digital capabilities.

Because the building blocks are interdependent, a shift in attention does not typically lead to deterioration in earlier building blocks. Rather, any given building block, once it has gained traction, will tend to get stronger as it interacts with other building blocks. Improvements in the accountability framework, for example, help a company ensure the continuous improvement and reuse of the components in its digital platform. Technical and business capabilities built into the digital platform make it possible to carry out experiments that will lead to meaningful customer insights. Customer insights help set priorities for the digital platform, the external developer platform, and even the operational backbone. A building block owner should take responsibility for the constant enhancement of each building block. In this way, companies can grow building blocks individually and as a whole.

Despite the pressures to address all the building blocks all the time, we found that companies made more progress when they took a strategic approach to building one or two blocks. In effect, they followed a roadmap for their critical initiatives to ensure meaningful progress without trying to introduce overwhelming organizational changes. Although the companies we studied did not necessarily have an explicit roadmap, they tended to invest initially in one or two building blocks rather than dabbling in all. These early limited initiatives spawned positive, impactful organizational changes. As is usually the case, focused investments generated faster progress.

A roadmap can help a company avoid two risks of a digital transformation: (1) dividing resources across so many building blocks that the company doesn’t make real progress on any of them or (2) becoming too focused on one or two building blocks for too long and failing to develop other building blocks that are also essential.

To help you define a roadmap that will work for your company, we will describe our interpretation of the journeys of three companies you’ve learned about throughout the book: Schneider Electric, Philips, and DBS Bank. Each of their journeys reflects their unique competencies and aspirations: by understanding the strategic choices the leaders at these three companies made, we hope to provide insights into the tradeoffs companies encounter and the kinds of strategic decisions that pay off.

The shape of a building block might change from roadmap to roadmap, but the shading stays the same. The building block’s shape reflects the company’s initial investment in developing it. Some shapes show a focused effort to create a building block in a brief period (i.e., 1–2 years); others show more extended attention over a few years. These shapes are intended to describe how each building block became embedded in the company’s organizational design. The task of building these five organizational capabilities is never complete. While the shapes indicate when the company made a commitment to developing a building block, they do not imply that the investment stops when a shape ends.

The individual roadmaps show the authors’ interpretation of how each company pieced together all the building blocks. Each company’s roadmap highlights which building block(s) served as the starting point for the digital transformation and how management shifted focus to new building blocks as early efforts gained traction. We do not depict all the experiments, the occasional false start, or sustaining investments. Rather we provide a picture of when and how leaders committed to each building block in the company’s digital transformation journey.

Schneider Electric

Schneider Electric’s digital journey highlights Schneider’s unique history and its vision to provide integrated energy management solutions by leveraging the Internet of Things, analytics, cloud, and artificial intelligence.4 During its long history, Schneider’s business had become so complex, that leaders probably had little choice but to invest in an operational backbone before trying to develop digital offerings. In 2014, Schneider Electric’s leaders started to discuss the business models made possible by the connectivity of customer assets. Though still under construction, the operational backbone that the company had been building for nearly five years had simplified core processes and systems enough to move forward with other building blocks.

Schneider Electric started experimenting with connected products within business units well before the company defined a digital strategy. Initially, the business units retained responsibility for new offerings, as they have with products. Like most companies, however, Schneider found it hard to sell customers on the value of early digital offerings. The company took advantage of strong relationships with a few large global customers who were willing to engage in finding new solutions for their unique energy management needs. This enabled the company to make an early focused investment in accumulating customer insights. Since then, Schneider’s Digital Services Factory team has adopted innovation approaches that proactively seek customer input.

Schneider Electric’s IT leaders recognized the need for a digital platform as the company’s digital vision unfolded. In particular, they defined what the company refers to as its EcoStruxure platform, intending it to facilitate the connectivity Schneider’s digital offerings would demand. IT leaders wanted to get ahead of business demand, so they built into EcoStruxure a set of enabling IoT infrastructure components and some early business components, such as subscription billing. The company has been adding components related to data analytics, including artificial intelligence, and common business components such as dashboarding and automated actions responding to alerts. Schneider now has a large repository of digital components that accelerate development of digital offerings.

As the portfolio of offerings grows, management has been able to shift focus from defining offerings and building core components to getting the accountabilities right. Schneider Electric leaders had recognized their technical challenges before they fully comprehended the organizational changes they needed. Even the Digital Transformation Team initially viewed its challenge as a technical one. More recently, the challenge of leveraging a digital platform across its diverse businesses has focused management attention on getting accountabilities right. A new high-profile digital business unit, established and governed at the executive level under the leadership of a chief digital officer, is taking on the challenge of developing the company’s accountability framework.

Schneider Electric’s foray into external developer partnerships is recent but leaders view its new developer platform as an important strategic initiative. The company has just started to build APIs to enable partners to connect to EcoStruxure components. The company continues to stage hackathons to identify more opportunities to build out its external developer platform and expand its marketplace, Schneider Electric Exchange.

Figure 7.3 depicts Schneider Electric’s development of its building blocks over the years.

Schneider Electric’s building block development (author interpretation)

Schneider Electric has benefited from its early start on developing an operational backbone and a digital vision that guided development of key infrastructure components in its digital platform. It has methodically pursued customer insights from valued customers that have produced digital offerings of value to a broader audience. Its external developer platform is expanding its offerings through partnerships.

Schneider leaders still view the status of the operational backbone as an obstacle to digital success. Many old complex companies will feel this pain. For Schneider Electric the greatest challenge is the accountability framework, which will become increasingly important as Schneider builds up its repositories of digital offerings and components. The accountability framework has proved difficult because Schneider is designed around its major business units and because the company is simultaneously building digital capabilities into its physical products—electrical equipment—and its digital offerings. This creates a complex environment for assigning accountabilities. Schneider’s digital business unit is trying to coordinate all of its technology efforts. That unit’s ability to continue to develop and enhance digital components—and convince business leaders to use them in their offerings—will be key to growing Schneider’s digital business.

Royal Philips

Royal Philips’s digital transformation began in the later stages of a digitization effort that was designed to turn around a struggling company.5 In 2014, the company announced its digital strategy: improving healthcare outcomes at lower cost. Its transformation journey has many themes similar to Schneider Electric’s.

Philips began its digitization efforts in 2011. By 2014, the company had successfully standardized two of the three processes (idea-to-market and market-to-order) that management felt were core to its business. Work on order-to-cash was still in progress when management attention shifted from the operational backbone to developing and commercializing new HealthTech offerings. This shift in focus has allowed Philips to aggressively pursue development of digital offerings, but it has required developing workarounds to support some new business processes, such as subscription billing services. Work on the operational backbone has been ongoing, and, in 2018, leaders are emphasizing the need for enterprise adoption of standardized order-to-cash processes.

Well before Philips initiated its digital transformation, the company had experimented with digital capabilities to create connected products within its product lines. To generate ideas for digital offerings, Philips initially relied on individual business units and on central labs like the Digital Accelerator Lab6 to accumulate customer insights. In 2015, Philips introduced HealthSuite Labs to engage healthcare providers, patients, and payers in intensive workshops to generate ideas for digital offerings that would solve their biggest problems.7 Philips has since ratcheted up the use of HealthSuite Labs, which—although resource intensive—help generate insights on how potential digital offerings can address customer problems.

IoT, analytics, artificial intelligence, and other digital technologies were at the heart of Philips’s digital vision, so the company started to develop HealthSuite Digital Platform (HSDP), a digital platform that captured the infrastructure capabilities enabling integration of data from various devices, systems, and other inputs. The company also started building a repository of business capabilities it called CDP². HSDP and CDP² provided reusable components that Philips could then configure into digital offerings. In 2015, Philips developed its first four digital offerings on its platforms. The company had 31 such offerings by 2017 and has been accelerating development of new offerings ever since.

Recognizing the vast number of services required to improve individual health, Philips envisioned early in its transformation that it would need to expand its digital offerings by including partner offerings. As we described in chapter 6, Philips started in 2016 to make HSDP components available via an external developer platform for this purpose. In 2018, leaders decided to scale back that effort, however, to concentrate on developing the company’s own digital components and offerings. The company continues to offer HSDP access to a small group of partners, and it has launched HealthSuite Insights to provide healthcare specific tools for building, maintaining, deploying, and scaling healthcare-related AI and data science solutions.8 The scaling back of the ExDP is temporary; it is still an important element of Philips’s long-term strategy.

During the company’s digitization transformation, the IT unit introduced cross-functional, Agile teams to enhance understanding between IT and business units as the company was implementing its operational backbone. The shift from selling products to developing integrated solutions further required Philips to rethink its accountability framework. In 2016 and 2017, Philips experimented with several alternatives ranging from having solution teams as a separate unit to having them more integrated into their market-facing organization. Philips is considering organizing around businesses that provide components and businesses that integrate those components into solutions. It expects its organization to be fluid as it learns what design is most effective.

As figure 7.4 shows, Philips, like Schneider Electric, was actively building an operational backbone even before its digital transformation. When leaders initiated the transformation, they recognized they would also need a digital platform. The building block for customer insights is a particularly challenging one in an industry like healthcare because of the large number of stakeholders (e.g., payers, providers, patients, and policymakers) and because these stakeholders have conflicting goals. HealthSuite Labs is a resource-intensive approach to developing customer solutions that provides deep insights into all stakeholders. Similar to Schneider, Philips is still wrestling with its accountability framework due to the complexity of its business as well as demands to insert digital capabilities into both products (which continue to generate the majority of its revenues) and new digital offerings. It is likely that Philips needs to make progress with its accountability framework before the company can extend broad third-party access to its digital platform. In the meantime, its AI-focused external developer platform will foster learning about how to build, manage, and drive value from third-party relationships.

Royal Philips’s building block development (author interpretation)

DBS Bank

As we noted in chapter 2, the digital vision at DBS has evolved over the last decade, but at the core of its vision is a belief that becoming more digital can improve the lives of customers.9 DBS’s earliest initiatives focused jointly on the operational backbone and customer insights. Figure 7.5 depicts our interpretation of the development of building blocks at DBS.

DBS building block development (author interpretation)

From 2009 to 2014, DBS focused on becoming “digital to the core,” transforming its operational backbone from fragmented and heterogeneous to standardized and rationalized. This transformation focused on operational excellence and engaged cross-functional teams to redesign core business processes. Process improvement became an organization-wide aspiration when the CEO established a goal of eliminating 100 million wasted customer hours. Employees managed to eliminate 240 million hours by 2014. More recently, DBS has been meeting ambitious goals to radically improve the velocity and reduce the cost of the operational backbone. These efforts have also made operational data and processes readily accessible to digital offerings.

DBS has put considerable emphasis over the last decade on developing customer insights. The bank’s initial desire to be innovative in the use of digital technology—to be a “22,000-person startup”—shifted quickly to focusing outward, on customers and customer journeys, to provide customers with simple, effortless banking. Starting in 2010, DBS formalized its commitments to both innovation and customer journeys by setting up organizational units to instill these concepts in the entire company. These units have taught test-and-learn concepts, design thinking, and customer journey analysis to most DBS employees. In 2013 the company set up a Customer Journey Design Lab to teach design thinking by doing and has since captured a raft of data from sensors on customer touchpoints so that employees can analyze customer habits and needs. Today, customer journey thinking is pervasive at DBS.

In 2012, DBS seamlessly integrated an internet and mobile services platform for businesses onto its core banking platform. That platform provided straight-through processing and easy access to data for all DBS business customers globally. Recognizing the potential of digital technologies, platform owners within individual business units started developing additional API-enabled components. Although independent business units sometimes duplicated efforts, they built hundreds of digital components. Over time, business units built repositories and created individual digital platforms. In 2016, DBS launched an entirely digital bank in India, called “digibank,” and reused that platform for a new digital bank in Indonesia a year later.

DBS began experimenting with new ways of working around 2011 with the introduction of new workspaces. About the same time, the company pushed responsibility for customer journeys to individual employees. Since then the company’s accountability framework has been gradually built on principles of empowerment and evidence-based decision making. In 2018, DBS shifted from projects to products in IT, so that owners of a digital offering take responsibility for its entire life cycle. At the same time, responsibility for developing digital platforms—meaning all the people, technical assets, and budgets that enable a meaningful set of offerings—was devolved to DBS’s individual business units. Each business unit’s digital platform has dual owners—a technology lead and a business leader—referred to as “two-in-a-box” because the organization chart lists two people. This management approach involves shared missions, goals, resources, metrics, and roadmaps for offerings. Leaders of the platforms receive coaching on how to strategize and manage their new business responsibilities.

As we noted in chapter 6, DBS was motivated to develop its external developer platform by the roaring success of a hackathon it organized with startups in 2017. Later the same year, DBS rolled out the world’s largest API-enabled banking platform accessible by third parties. The external developer platform is a strategic element of DBS’s future growth plans. The strategic importance of the ExDP has motivated the company to rationalize the multiple digital platforms that reside in individual business units.

As a financial institution, DBS is not connecting its digital business to physical products the way Schneider and Philips are. This difference has allowed the company to focus its operational backbone efforts on enhancing customer experience with digital channels and on empowering employees with data. Now, however, the company distinguishes between platforms that support enterprise functions like finance, HR, and legal, and platforms that support products. We refer to the former as the operational backbone and the latter as the digital platform. Distinguishing between these two types of platforms has helped DBS clarify accountabilities for digital offerings and platforms and will facilitate further development of its external developer platform.

One striking element of the DBS story is its extraordinary investment in people. DBS has invested heavily in employee training, mentoring, and skill development, which has instilled a culture of evidence-based decision making. This investment is reaping benefits as the company continues to build and leverage deep customer insights and then convert those insights into valued digital offerings.

Recommendations for Your Digital Roadmap

The four roadmaps we described in this chapter highlight the different approaches companies are taking to their digital transformations. Leaders cannot prioritize everything at once, so they move the needle incrementally on building blocks that are most likely to facilitate a successful transformation.

Although we do not see a single pattern emerging over the four cases in this chapter, we see some generalizable findings about digital roadmaps. These lead to the following recommendations for developing your roadmap:

Fix the backbone Most established companies find that their operational backbone is an impediment to digital success and that they must address its worst deficiencies before they can start to develop digital offerings. Meanwhile, companies with a robust operational backbone can move on to other building blocks. As companies feel an urgency to move forward with digital initiatives, they need to focus strategically on fixing core capabilities that really are essential support for digital business.

Don’t put off your digital platform for long Companies usually build some early digital services or offerings before they recognize the need for a digital platform. They may simply attach digital components to their operational backbone or they may build a monolithic digital offering. Our sense is that, early on in a digital transformation, this approach can support rapid, local experimentation and learning. It might be a good way to learn about digital value propositions, but pretty quickly companies need to start defining an architecture that supports developing reusable components and offerings. The longer you wait, the more difficult it becomes to create a sustainable technology base for your offerings.

Synchronize your customer insights and digital platform development Some companies start their transformations with a clear picture of what their value proposition for digital offerings will be. They tend to start building digital platforms before they have accumulated shared customer insights. Other companies work to get to know their customers’ demands to help guide development of digital offerings. Our sense is that either approach can succeed and, in the short term, can accelerate development of a single building block. Having a platform of useful components can enable rapid experimentation for customer insights. Conversely, experimentation can help clarify what components are needed. Whichever one they start with, companies need to plan for development of the other, complementary asset. The risk facing companies that move forward on digital platforms without a clear understanding of customer demands is that they can easily invest in components and offerings no one wants—while missing opportunities to create digital offerings that would be valued. The risk of focusing too narrowly on customer insights will be a temptation to respond to those insights by quickly building monolithic offerings that will be very difficult to reuse, scale, or improve.

Start assigning accountabilities The sooner you can adopt an accountability framework for digital the better. But it will be difficult to establish accountabilities until you have high-level clarity around digital offerings and components. Balancing autonomy with alignment starts with recognizing the boundaries between distinct living assets. This is especially challenging for engineering companies that have well-established, rigorous, multi-year product development processes. At these companies, software development is located in multiple parts of the company, which will likely complicate both autonomy and alignment. Experiments within innovation labs or the IT unit, particularly experiments that involve iterative, Agile development, can facilitate some early learning.

Don’t rush into an ExDP The external developer platform, as we mentioned in chapter 6, benefits greatly from the maturity of the other four digital assets. Unless your value proposition relies heavily on building an ecosystem from the start, this building block should wait until the other building blocks are on solid ground.

Keep learning and building Perhaps this goes without saying, but it’s probably impossible to simultaneously focus on all five building blocks, at least until some of the building blocks are well established. At the same time, the work on any building block is never complete. The idea is to sequence early development of building blocks based on your most pressing needs. Then develop habits that foster learning and continuous improvement on each individual building block as well as the whole.

You might be wishing for a more explicit plan of attack for your digital transformation than we have provided in this chapter. Be wary, though, if someone offers you such a template. Digital transformations are massive—and still fairly new. Leaders must be prepared to learn what does and doesn’t work and adjust course. There is no single path or target business design defining how to become a successful digital business. You need to embark on a journey and allow your digital business to evolve.

We expect that what you’d most like to do is restructure your company to emphasize the growing importance of digital. Indeed, many of the initiatives we cite in this book involve some important new structures like digital business units and customer experience labs. But remember: a digital transformation is mostly not about structure. Do not try to succeed in the digital economy with pre-digital approaches!

We are confident that the transformation journey involves developing five digital building blocks: shared customer insights, an operational backbone, a digital platform, an accountability framework, and an external developer platform. The journey is long and the target isn’t clear. Nonetheless, our suggestion is: Don’t delay building these assets. Get out a napkin and draw your roadmap. What does your roadmap look like?

Notes