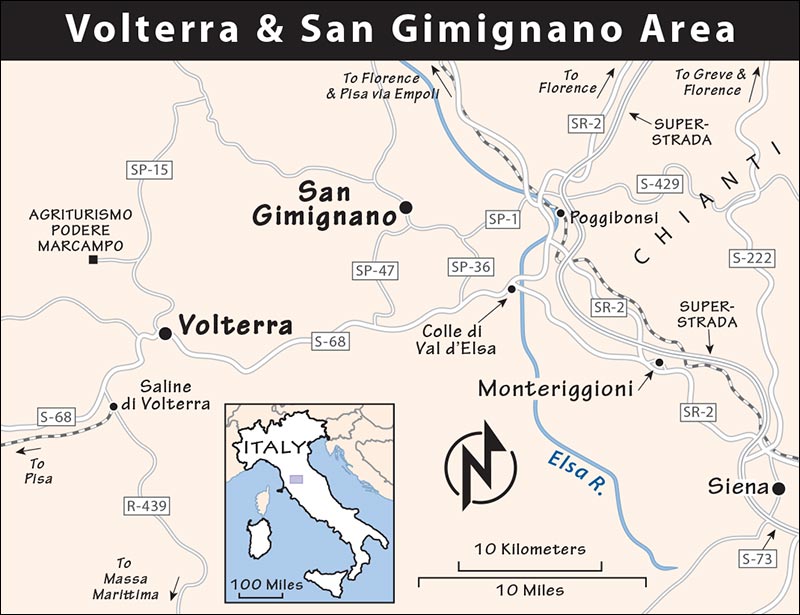

Map: Volterra & San Gimignano Area

This fine duo of hill towns—perhaps Italy’s most underrated and most overrated, respectively—sit just a half-hour drive apart in the middle of the triangle formed by three major destinations: Florence, Siena, and Pisa. San Gimignano is the region’s glamour girl, getting all the fawning attention from passing tour buses. And a quick stroll through its core, in the shadows of its 14 surviving medieval towers, is a delight. But once you’ve seen it, you’ve seen it...and that’s when you head for Volterra. Volterra isn’t as eye-catching as San Gimignano, but it has unmistakable authenticity and surprising depth, richly rewarding travelers adventurous enough to break out of the San Gimignano rut. With its many engaging museums, Volterra offers the best sightseeing of all of Italy’s small hill towns.

These towns work best for drivers, who can easily reach both in one go. Volterra is farther off the main Florence-Siena road, but it’s near the main coastal highway connecting the north (Pisa, Lucca, and Cinque Terre) and south (Montalcino/Montepulciano and Rome).

If you’re relying on public transportation, both towns are reachable—to a point. Visiting either one by bus from Florence or Siena requires a longer-than-it-should-be trek, often with a change (in Colle di Val d’Elsa for Volterra, in Poggibonsi for San Gimignano). Volterra can also be reached by a train-and-bus combination from La Spezia, Pisa, or Florence (transfer to a bus in Pontedera). See each town’s “Connections” section for details.

San Gimignano is better connected, but Volterra merits the additional effort. Note that while these towns are only about a 30-minute drive apart, they’re poorly connected to each other by public transit (requiring an infrequent two-hour connection).

Volterra and San Gimignano are a handy yin-and-yang duo. Ideally, you’ll overnight in one town and visit the other either as a side-trip or en route. Sleeping in Volterra lets you really settle into a charming, real-feeling burg with good restaurants, but it forces you to visit San Gimignano during the day, when it’s busiest. Sleeping in San Gimignano lets you enjoy that gorgeous town when it’s relatively quiet, but some visitors find it too quiet—less interesting to linger in than Volterra. Ultimately I’d aim to sleep in Volterra, and try to visit San Gimignano as early or late in the day as is practical (to avoid crowds).

Encircled by impressive walls and topped with a grand fortress, Volterra perches high above the rich farmland surrounding it. More than 2,000 years ago, Volterra was one of the most important Etruscan cities, and much larger than we see today. Greek-trained Etruscan artists worked here, leaving a significant stash of art, particularly funerary urns. Eventually Volterra was absorbed into the Roman Empire, and for centuries it was an independent city-state. Volterra fought bitterly against the Florentines, but like many Tuscan towns, it lost in the end and was given a Medici fortress atop the city to “protect” its citizens.

Unlike other famous towns in Tuscany, Volterra feels neither cutesy nor touristy...but real, vibrant, and almost oblivious to the allure of the tourist dollar. Millennia past its prime, Volterra seems to have settled into a well-worn groove; locals are resistant to change. At a town meeting about whether to run high-speed Internet cable to the town, a local grumbled, “The Etruscans didn’t need it—why do we?” This stubbornness helps make Volterra a refreshing change of pace from its more aggressively commercial neighbors. Volterra also boasts some interesting sights for a small town, from an ancient Roman theater, to a finely decorated Pisan Romanesque cathedral, to an excellent museum of Etruscan artifacts. And most evenings, charming Annie and Claudia give a delightful, one-hour guided town walk sure to help you appreciate their city (see “Tours in Volterra,” later). All in all, Volterra is my favorite small town in Tuscany.

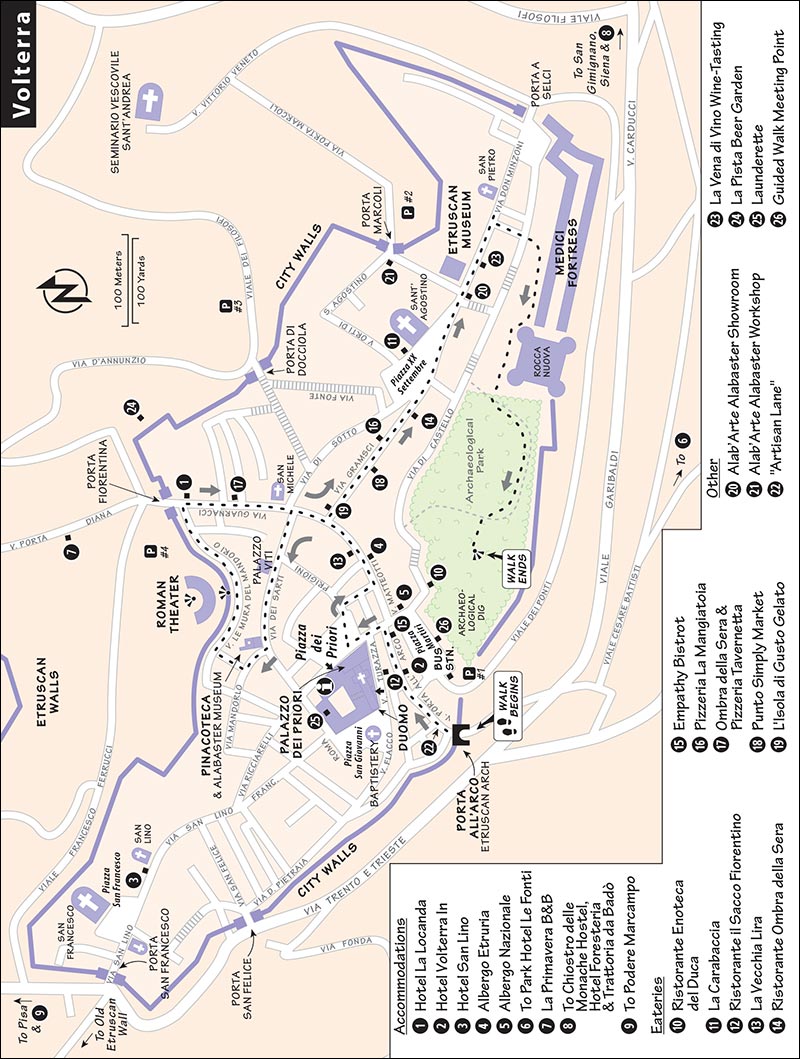

Compact and walkable, Volterra (pop. 11,000—6,000 inside the old wall) stretches out from the pleasant Piazza dei Priori to the old city gates and beyond. Be ready for some steep walking: While the spine of the city from the main square to the Etruscan Museum is fairly level, nearly everything else involves a climb.

The helpful TI is on the main square, at Piazza dei Priori 19 (daily 9:30-13:00 & 14:00-18:00, tel. 0588-87257, www.volterratur.it). The TI’s excellent €5 audioguide narrates 20 stops (2-for-1 discount with this book). Their free Handicraft in Volterra booklet is useful for understanding the town’s traditional artisans. Check the TI website for details on frequent summer festivals and concerts.

By Public Transport: Buses stop at Piazza Martiri della Libertà in the town center. Train travelers can reach the town with a short bus ride (see “Volterra Connections,” later).

By Car: Don’t drive into the town center; it’s prohibited except for locals (and you’ll get a huge fine). It’s easiest to simply wind to the top where the road ends at Piazza Martiri della Libertà. (Halfway up the hill, there’s a confusing hard right—don’t take it; keep going straight uphill under the wall.) Immediately before the Piazza Martiri bus roundabout is the entry to an underground garage (€2/hour, €15/day, keep ticket and pay as you leave). It’s safe, and you pop out within a few blocks of nearly all my recommended hotels and sights.

Parking lots ring the town walls (around €2/hour; try the handy-but-small lot facing the Roman Theater and Porta Fiorentina gate). Behind town, a lot named Docciola is free, but it requires a steep climb from the Porta di Docciola gate up into town.

Wherever you park, be sure it’s permitted—stick to parking lots and pay street parking (indicated with blue lines). If you’re staying in town, check with your hotel about the best parking options.

Volterra Card: This €14 card covers all the main sights—except for the Palazzo Viti (valid 72 hours, buy at any covered sight). Without the card, the Etruscan Museum and Pinacoteca are €8 each, and the Palazzo Priori and Archaeological Park are €5 each. If traveling with kids, ask about the family card, an especially good deal (€22 for 1-2 adults and up to 3 kids under 16).

Market Day: The market is on Saturday morning near the Roman Theater (8:00-13:00, Nov-March it moves to Piazza dei Priori). The TI hands out a list of other market days in the area.

Festivals: Volterra’s Medieval Festival takes place on the third and fourth Sundays of August. Fall is a popular time for food festivals. Notte Rossa, on the second Saturday in September, fills the town with music all night.

Laundry: The handy self-service Lavanderia Azzurra is just off the main square (change machine, daily 7:00-23:00, Via Roma 7, tel. 0588-80030). Their next-door dry-cleaning shop also provides wash-and-dry services that usually take about 24 hours (Mon-Fri 8:30-13:00 & 15:30-20:00, Sat 8:30-13:00, closed Sun).

Annie Adair (also listed individually, next) and her colleague Claudia Meucci offer a great one-hour, English-only introductory walking tour of Volterra for €10. The walk touches on Volterra’s Etruscan, Roman, and medieval history, as well as the contemporary cultural scene (daily April-Oct, rain or shine—Mon and Wed at 12:30, other days at 18:00; meet in front of alabaster shop on Piazza Martiri della Libertà, no need to reserve, tours run with a minimum of 3 people or €30; www.volterrawalkingtour.com or www.tuscantour.com, info@volterrawalkingtour.com). There’s no better way to spend €10 and one hour in this city. I mean it. Don’t miss this beautiful experience.

American Annie Adair is an excellent guide for private, in-depth tours of Volterra (€60/hour, minimum 2 hours). Her husband Francesco, an easy-going sommelier and wine critic, leads a “Wine Tasting 101” crash course in sampling Tuscan wines (€50/hour per group, plus cost of wine). For more in-depth experiences, Annie and Francesco offer excursions to a nearby honey farm, alabaster quarry, and winery, or a more wine-focused trip to Montalcino or the heart of Chianti (about €450/day for 2-3 people) and can even organize Tuscan weddings (mobile 347-143-5004, www.tuscantour.com, info@tuscantour.com).

▲Etruscan Arch (Porta all’Arco)

“Artisan Lane” (Via Porta all’Arco)

Pinacoteca and Alabaster Museum

▲▲Etruscan Museum (Museo Etrusco Guarnacci)

▲La Vena di Vino (Wine Tasting with Bruno and Lucio)

Medici Fortress and Archaeological Park

(See “Volterra” map, here.)

I’ve linked these sights with handy walking directions.

• Begin at the Etruscan Arch at the bottom of Via Porta all’Arco (about 4 blocks below the main square, Piazza dei Priori).

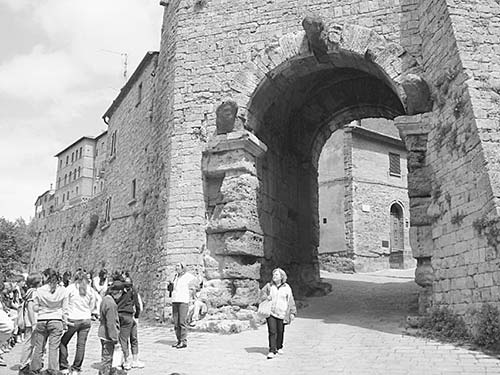

Volterra’s renowned Etruscan arch was built of massive stones in the fourth century B.C. Volterra’s original wall was four miles around—twice the size of the wall that encircles it today. Imagine: This city had 20,000 people four centuries before Christ. Volterra was a key trading center and one of 12 leading towns in the confederation of Etruria Propria. The three seriously eroded heads, dating from the first century B.C., show what happens when you leave something outside for 2,000 years. The newer stones are part of the 13th-century city wall, which incorporated parts of the much older Etruscan wall.

A plaque just outside remembers June 30, 1944. That night, Nazi forces were planning to blow up the arch to slow the Allied advance. To save their treasured landmark, Volterrans ripped up the stones that pave Via Porta all’Arco, plugged up the gate, and managed to convince the Nazi commander that there was no need to blow up the arch. Today, all the paving stones are back in their places, and like silent heroes, they welcome you through the oldest standing gate into Volterra. Locals claim this as the oldest surviving round arch of the Etruscan age; some experts believe this is where the Romans got the idea for using a keystone in their arches.

• Go through the arch and head up Via Porta all’Arco, which I like to call...

This steep and atmospheric lane is lined with interesting shops featuring the work of artisans and producers. Because of its alabaster heritage, Volterra developed a tradition of craftsmanship and artistry, and today you’ll find a rich variety of handiwork (shops generally open Mon-Sat 10:00-13:00 & 16:00-19:00, closed Sun).

From the Etruscan Arch, browse your way up the hill, checking out these shops and items (listed from bottom to top): alabaster shops (#57 and #45); book bindery and papery (#26); jewelry (#25); etchings (#23); and bronze work (#6).

• Reaching the top of Via Porta all’Arco, turn left and walk a few steps into Volterra’s main square, Piazza dei Priori. It’s dominated by the...

Volterra’s City Hall, built about 1200, claims to be the oldest of any Tuscan city-state. It clearly inspired the more famous Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. Town halls like this are emblematic of an era when city-states were powerful. They were architectural exclamation points declaring that, around here, no pope or emperor called the shots. Towns such as Volterra were truly city-states—proudly independent and relatively democratic. They had their own armies, taxes, and even weights and measures. Notice the horizontal “cane” cut into the City Hall wall (10 yards to the right of the door). For a thousand years, this square hosted a market, and the “cane” was the local yardstick. You can pay to see the council chambers, and to climb to the top of the bell tower.

Cost and Hours: €5, includes council chambers and tower climb, covered by Volterra Card, daily 10:30-17:30, Nov-mid-March until 16:30, tower closed in bad weather.

• Facing the City Hall, notice the black-and-white-striped wall to the right (set back from the square). The little back door in that wall leads into Volterra’s cathedral. (For a thousand years the bishop has lived next door, conveniently right above the TI.)

This church, which may be closed for renovation until 2020, is not as elaborate as its cousin in Pisa, but it is a beautiful example of the Pisan Romanesque style. The simple 13th-century facade conceals a more intricate interior (rebuilt in the late 16th and 19th centuries), with a central nave flanked by monolithic stucco columns painted to imitate pink granite, and topped by a gilded, coffered ceiling. Just past the pulpit on the right (at the Rosary Chapel), check out the Annunciation, painted in 1497 by Mariotto Albertinelli and Fra Bartolomeo (both were students of Fra Angelico). The two, friends since childhood, delicately give worshippers a way to see Mary “conceived by the Holy Spirit.” Note the vibrant colors, exaggerated perspective, and Mary’s contrapposto pose—all attributes of the Renaissance.

Cost and Hours: Free, daily 8:00-12:30 & 15:00-18:00, Nov-Feb until 17:00, closed Fri 12:30-16:00 for cleaning.

• Facing the cathedral, circle to the left (passing a 1960 carving of St. Linus, the second pope and friend of St. Peter, who was born here) and go back into the main square, Piazza dei Priori. Face the City Hall, and go down the street to the left; after one short block, turn left on...

The town’s main drag, named after the popular Socialist leader Giacomo Matteotti (killed by the fascists in 1924), provides a good cultural scavenger hunt.

At #1, on the left, is a typical Italian bank security door. (Step in and say, “Beam me up, Scotty.”) Back outside, stand at the corner and look up and all around. Find the medieval griffin torch-holder—symbol of Volterra, looking down Via Matteotti—and imagine it holding a flaming torch. The pharmacy sports the symbol of its medieval guild. Across the street from the bank, #2 is the base of what was a San Gimignano-style fortified Tuscan tower. Look up and imagine heavy beams cantilevered out, supporting extra wooden rooms and balconies crowding out over the street. Throughout Tuscany, today’s stark and stony old building fronts once supported a tangle of wooden extensions.

As you head down Via Matteotti, notice how the doors show centuries of refitting work. Doors that once led to these extra rooms are now partially bricked up to make windows. Contemplate urban density in the 14th century, before the plague thinned out the population. Be careful: A wild boar (a local delicacy) awaits you at #10.

At #12, on the right, notice the line of doorbells: This typical palace, once the home of a single rich family, is now occupied by many middle-class families. After the social revolution in the 18th century and the rise of the middle class, former palaces were condominium-ized. Even so, like in Dr. Zhivago, the original family still lives here. Apartment #1 is the home of Count Guidi.

On the right at #16, pop in to the alabaster showroom. Alabaster, mined nearby, has long been a big industry here. Volterra alabaster—softer and more translucent than marble—was sliced thin to serve as windows for Italy’s medieval churches.

At #19, the recommended La Vecchia Lira is a lively cafeteria and restaurant. The Bar L’Incontro across the street is a favorite for breakfast and pastries; in the summer, they sell homemade gelato, while in the winter they make chocolates. In the evening, it’s a bustling local spot for a drink.

Across the way, side-trip 10 steps up Vicolo delle Prigioni to the fun Panificio Rosetti bakery. They’re happy to sell small quantities if you want to try the local cantuccini (almond biscotti) or another treat.

Continue on Via Matteotti to the end of the block. At #51, on the left, a bit of Etruscan wall is artfully used to display more alabaster art. And #56A is the alabaster art gallery of Paolo Sabatini, who specializes in unique, contemporary sculptures.

By the way, you can only buy a package of cigarettes at the machine in the wall just to the right—labeled “Vietato ai Minori” (forbidden to minors)—by inserting an Italian national health care card to prove you’re over 18.

Locals gather early each evening at Osteria dei Poeti (at #57) for some of the best cocktails in town—served with free munchies. The cinema is across the street. Movies in Italy are rarely in versione originale; Italians are used to getting their movies dubbed into Italian. To bring some culture to this little town, they also show live broadcasts of operas and concerts (advertised in the window).

On the corner, at #66, another Tuscan tower marks the end of the street. This noble house had a ground floor with no interior access to the safe upper floors. Rope ladders were used to get upstairs. The tiny door was wide enough to let in your skinny friends...but definitely not anyone wearing armor and carrying big weapons.

Across the little square stands the ancient Church of St. Michael. After long years of barbarian chaos, the Langobards moved in from the north and asserted law and order in places like Volterra. That generally included building a Christian church on the old Roman forum to symbolically claim and tame the center of town. The church standing here today is Romanesque, dating from the 12th century.

Around the right side, find the crude little guy and the smiling octopus under its eaves—they’ve been making faces at the passing crowds for 800 years.

• From here you have options. Three more sights—Palazzo Viti (fancy old palace), the Pinacoteca (Volterra’s main painting gallery), and the Alabaster Museum (within the Pinacoteca building)—are a short stroll down Via dei Sarti: From the end of Via Matteotti, turn left. If you want to skip straight down to the Roman Theater, just head straight from the end of Via Matteotti onto Via Guarnacci, then turn left when you get to the Porta Fiorentina (Florence Gate). To head directly to Volterra’s top sight, the Etruscan Museum, just turn around, walk a block back up Via Matteotti, turn left on Via Gramsci, and follow it all the way through Piazza XX Settembre up Via Don Minzoni to the museum.

Or linger a bit while making your decision over a glass of wine at Enoteca Scali, just across the street at Via Guarnacci 3. Friendly Massimo and Patrizia sell a vast selection of wines and local delicacies in an inviting atmosphere.

Palazzo Viti takes you behind the rustic, heavy stone walls of the city to see how the wealthy lived—in this case, rich from the 19th-century alabaster trade. This time warp is popular with Italian movie directors. With 12 rooms on one floor open to the public, Palazzo Viti feels remarkably lived in—because it is. Behind the ropes you’ll see intimate family photos. You’ll often find Signora Viti herself selling admission tickets. Your visit ends in the cellar with a short wine tasting.

Cost and Hours: €5, daily 10:00-13:00 & 14:30-18:30, by appointment only Nov-March, Via dei Sarti 41, tel. 0588-84047, www.palazzoviti.it, info@palazzoviti.it.

Visiting the Palazzo: The elegant interior is compact and well-described. You’ll climb up a stately staircase, buy your ticket, and head into the grand ballroom. From here, you’ll tour the blue-hued dining room (with slice-of-life Chinese scenes painted on rice paper); the salon of battles (with warfare paintings on the walls); and the long hall of temporary exhibits. Looping back, you’ll see the porcelain hall (decorated with priceless plates) and the inviting library (notice the delicate lamp with a finely carved alabaster lampshade).

The Brachettone Salon is named for the local artist responsible for the small sketch of near-nudes hanging just left of the door into the next room. Brachettone (from brache, “pants”) is the artistic nickname for Volterra-born Daniele Ricciarelli, who owns the dubious distinction of having painted all those wispy loincloths over the genitalia of Michelangelo’s figures in the Sistine Chapel. (In this drawing, notice a similar aversion to showing the full monty...though everything-but is fair game.) On the table, notice the family wedding photo with Pope John Paul II presiding. In the red room, a portrait of Giuseppe Viti (looking like Pavarotti) hangs next to the exit door. He’s the man who purchased the place in 1850. Your visit ends with bedrooms and a dressing room, making it easy to imagine how the other half lived.

Your Palazzo Viti ticket also gets you a fine little cheese, salami, and wine tasting. As you leave the palace, climb down into the cool cellar (used as a disco on some weekends), where you can pop into a Roman cistern, marvel at an Etruscan well, and enjoy a friendly sit-down snack. Take full advantage of this tasty extra.

• A block past Palazzo Viti, also on Via dei Sarti, is the...

The Pinacoteca fills a 15th-century palace with fine paintings that feel more Florentine than Sienese—a reminder of whose domain this town was in. You’ll see a stunning altarpiece by Taddeo di Bartolo, once displayed in the original residence. You’ll also find roomfuls of gilded altarpieces and saintly statues, as well as a trio of striking High Renaissance altar paintings by Signorelli, Fiorentino, and Ghirlandaio.

Cost and Hours: €8, covered by Volterra Card, daily 9:00-19:00, Nov-mid-March 10:00-16:30, Via dei Sarti 1, tel. 0588-87580.

• Exiting the museum, circle right along the side of the museum building into the tunnel-like Passo del Gualduccio passage (which leads to the parking-lot square); turn right and walk along the wall, with fine views of the...

Built in the first century A.D., this well-preserved theater has good acoustics. With this fine aerial view from the city wall promenade, there’s no reason to pay to enter (although it is covered by the Volterra Card). The 13th-century wall that you’re standing on divided the theater from the town center...so, naturally, the theater became the town dump. Over time, the theater was forgotten—covered in the garbage of Volterra. It was rediscovered in the 1950s and excavated.

The stage wall (immediately in front of the theater seats) was standard Roman design—with three levels from which actors would appear: one level for mortals, one for heroes, and the top one for gods. Parts of two levels still stand. Gods leaped out onto the third level for the last time around the third century A.D., which is when the town began to use the theater stones to build fancy baths instead. You can see the scant remains of the baths behind the theater, including the little round sauna in the far corner with brick supports that raise the heated floor.

From this vantage point, you can trace Volterra’s vast Etruscan wall. Find the church in the distance, on the left, and notice the stones just below. They are from the Etruscan wall that followed the ridge into the valley and defined Volterra in the fourth century B.C.

• From the Roman Theater viewpoint, continue along the wall downhill to the T-intersection (the old gate, Porta Fiorentina, with fine wooden medieval doors, is on your left) and turn right, making your way uphill on Via Guarnacci back to Via Matteotti. A block up Via Matteotti, you can’t miss the wide, pedestrianized shopping street called Via Gramsci. Follow this up to Piazza XX Settembre, walk through that leafy square, and continue uphill on Via Don Minzoni. Watch on your left for the...

Filled top to bottom with rare Etruscan artifacts, this museum—even with few English explanations and its dusty, old-school style—makes it easy to appreciate how advanced this pre-Roman culture was.

Cost and Hours: €8, covered by Volterra Card, daily 9:00-19:00, Nov-mid-March 10:00-16:30, audioguide-€3, Via Don Minzoni 15, tel. 0588-86347, www.comune.volterra.pi.it/english.

Visiting the Museum: The museum’s three floors feel dusty and disorganized. As there are scarcely any English explanations, consider the serious but interesting audioguide; the information below hits the highlights. There’s an inviting public garden out back.

The collection starts on the ground floor with a small gathering of pre-Etruscan Villanovian artifacts (c. 1500 B.C.), with the oldest items to the left as you enter. To the right are an impressive warrior’s hat and a remarkable, richly decorated, double-spouted military flask (for wine and water). Look down to see Etruscan foundations and a road (the discovery of which foiled the museum’s attempt to build an elevator here). It’s mind-boggling to think that 20,000 people lived within the town’s Etruscan walls in 400 B.C.

Filling the rest of the ground floor is a vast collection of Etruscan funerary urns (dating from the seventh to the first century B.C.). Designed to contain the ashes of cremated loved ones, each urn is tenderly carved with a unique scene, offering a peek into the still-mysterious Etruscan society. Etruscan urns have two parts: The casket on the bottom contained the remains (with elaborately carved panels), while the lid was decorated with a sculpture of the departed.

First pay attention to the people on top. While contemporaries of the Greeks, the Etruscans were more libertine. Their religion was less demanding, and their women were a respected part of both the social and public spheres. Women and men alike are depicted lounging on Etruscan urns. While they seem to be just hanging out, the lounging dead were actually offering the gods a banquet—in order to gain the Etruscan equivalent of salvation. Etruscans really did lounge like this in front of a table, but this banquet had eternal consequences. The dearly departed are often depicted holding blank wax tablets (symbolizing blank new lives in the next world). Men hold containers that would generally be used at banquets, including libation cups for offering wine to the gods. The women are finely dressed, sometimes holding a pomegranate (symbolizing fertility) or a mirror. Look at the faces, and imagine the lives they lived and the loved ones they left behind.

Now tune into the reliefs carved into the fronts of the caskets. The motifs vary widely, from floral patterns to mystical animals (such as a Starbucks-like mermaid) to parades of magistrates. Most show journeys on horseback—appropriate for someone leaving this world and entering the next. Some show the fabled horseback-and-carriage ride to the underworld, where the dead are greeted by Charon, an underworld demon, with his hammer and pointy ears.

While the finer urns are carved of alabaster, most are made of limestone. Originally they were colorfully painted. Many lids are mismatched—casualties of reckless 18th- and 19th-century archaeological digs.

Head upstairs to the first floor. You’ll enter a room with a circular mosaic in the floor (a Roman original, found in Volterra and transplanted here). Explore more treasures in a series of urn-filled rooms.

Fans of Alberto Giacometti will be amazed at how the tall, skinny figure called The Evening Shadow (L’Ombra della Sera, third century B.C.) looks just like the modern Swiss sculptor’s work—but 2,500 years older. This is an example of the ex-voto bronze statues that the Etruscans created in thanks to the gods. With his supremely lanky frame, distinctive wavy hairdo, and inscrutable Mona Lisa smirk, this Etruscan lad captures the illusion of a shadow stretching long, late in the day. Admire the sheer artistry of the statue; with its right foot shifted slightly forward, it even hints at the contrapposto pose that would become common in this same region during the Renaissance, two millennia later.

The museum’s other top piece is the Urn of the Spouses (Urna degli Sposi, first century B.C.). It’s unique for various reasons, including its material (it’s terra-cotta—a relatively rare material for these funerary urns) and its depiction of two people rather than one. Looking at this elderly couple, it’s easy to imagine the long life they spent together and their desire to pass eternity lounging with each other at a banquet for the gods.

Other highlights include alabaster urns with more Greek myths, ex-voto water-bearer statues, kraters (vases with handles used for mixing water and wine), bronze hand mirrors, exquisite golden jewelry that would still be fashionable today, a battle helmet ominously dented at the left temple, black glazed pottery, and hundreds of ancient coins.

The top floor features a re-created gravesite, with several neatly aligned urns and artifacts that would have been buried with the deceased. Some of these were funeral dowries that the dead would pack along—including mirrors, coins, hardware for vases, votive statues, pots, pans, and jewelry.

• After your visit, duck across the street to the alabaster showroom and the wine bar (both described next).

Across from the Etruscan Museum, Alab’Arte offers a fun peek into the art of alabaster. Their powdery workshop is directly opposite the shop, a block down a narrow lane, Via Porta Marcoli (near the wall). Here you can watch Roberto Chiti and Giorgio Finazzo at work. (Everything—including Roberto and Giorgio—is covered in a fine white dust.) Lighting shows off the translucent quality of the stone and the expertise of these artists, who are delighted to share their art with visitors. This is not a touristy guided visit, but something far more special: the chance to see busy artisans practicing their craft. For more such artisans in action, visit “Artisan Lane” (Via Porta all’Arco), described earlier, or ask the TI for their list of the town’s many workshops open to the public.

Cost and Hours: Free, showroom—daily 10:00-13:00 & 15:00-19:00, closed Nov-Feb, Via Don Minzoni 18; workshop—Mon-Sat 10:00-12:30 & 15:00-19:00, closed Sun, Via Orti Sant’Agostino 28, tel. 340-718-7189, www.alabarte.com.

La Vena di Vino, also just across from the Etruscan Museum, is a fun enoteca where two guys who have devoted themselves to the wonders of wine share it with a fun-loving passion. Each day Bruno and Lucio open six or eight bottles, serve your choice by the glass, pair it with characteristic munchies, and offer fine music (guitars available for patrons) and an unusual decor (the place is strewn with bras). Hang out here with the local characters. This is your chance to try the Super Tuscan wine—a creative mix of international grapes grown in Tuscany. According to Bruno, the Brunello (€7/glass) is just right with wild boar, and the Super Tuscan (€6-7/glass) is perfect for meditation. Although Volterra is famously quiet late at night, this place is full of action.

Cost and Hours: Pay per glass, open Wed-Mon 11:30-24:00, closed Tue, Nov-Feb open Sat-Sun only, Via Don Minzoni 30, tel. 0588-81491, www.lavenadivino.com.

• Volterra’s final sight is perched atop the hill just above the wine bar. Climb up one of the lanes nearby, then walk (to the right) along the formidable wall to find the park.

The Parco Archeologico marks what was the acropolis of Volterra from 1500 B.C. until A.D. 1472, when Florence conquered the pesky city. The Florentines burned Volterra’s political and historic center, turning it into a grassy commons and building the adjacent Medici Fortezza. The old fortress—a symbol of Florentine dominance—now keeps people in rather than out. It’s a maximum-security prison housing only about 150 special prisoners.

The park sprawling next to the fortress (toward the town center) is a rare, grassy meadow at the top of a rustic hill town—a favorite place for locals to relax and picnic on a sunny day. Nearby are the scant remains of the acropolis, which can be viewed through the fence for free, or entered for a fee. Of more interest to antiquities enthusiasts is the acropolis’ first-century A.D. Roman cistern. You can descend 40 tight spiral steps to stand in a chamber that once held about 250,000 gallons of water, enough to provide for more than a thousand people.

Cost and Hours: Park—free, open until 20:00 in peak of summer, shorter hours off-season; acropolis and cistern—€5, covered by Volterra Card, daily 10:30-17:30, closes at 16:30 off-season.

La Pista: Volterra is pretty quiet at night. For a little action during summer evenings you can venture just outside the wall to La Pista, a Tuscan family-friendly neighborhood beer-garden kind of hang-out (DJ on weekends, snacks and drinks sold, playground, closed off-season). It’s outside the Porta Fiorentina (100 yards to the right in the shadow of the wall).

Passeggiata: As they have for generations, Volterrans young and old stroll during the cool of the early evening. The main cruising is along Via Gramsci and Via Matteotti to the main square, Piazza dei Priori.

Aperitivo: Each evening several bars put out little buffet spreads free with a drink to attract a crowd. Bars popular for their aperitivo include VolaTerra (Via Turazza 5, next to City Hall), L’Incontro (Via Matteotti 19), and Bar dei Poeti (across from the cinema, Via Matteotti 57). And the gang at La Vena di Vino (described earlier, under “Sights in Volterra”) always seems ready for a good time.

Volterra has plenty of places offering a good night’s sleep at a fair price. Lodgings outside the old town are generally a bit cheaper (and easier for drivers). But keep in mind that these places involve not just walking, but steep walking.

$$ Hotel La Locanda feels stately and old-fashioned. This well-located place (just inside Porta Fiorentina, near the Roman Theater and parking lot) rents 18 rooms with flowery decor and modern comforts (RS%, family rooms, air-con, elevator, Via Guarnacci 24, tel. 0588-81547, www.hotel-lalocanda.com, staff@hotel-lalocanda.com, Irina).

$$ Hotel Volterra In, opened in 2015, is fresh, tasteful, and in a central-yet-quiet location. Marco rents 12 bright and spacious rooms with thoughtful, upscale touches and a hearty buffet breakfast (RS%, air-con, elevator, Via Porta all’Arco 37, tel. 0588-86820, www.hotelvolterrain.it, info@hotelvolterrain.it).

$$ Hotel San Lino fills a former convent with 42 modern, nondescript rooms at the sleepy lower end of town—close to the Porta San Francesco gate, and about a five-minute uphill walk to the main drag. Although it’s within the town walls, it doesn’t feel like it: The hotel has a fine swimming pool and view terrace and is the only in-town option that’s convenient for drivers, who can pay to park at the on-site garage (pricey “superior” rooms include parking—worthwhile only for drivers, air-con, elevator, closed Nov-Feb, Via San Lino 26, tel. 0588-85250, www.hotelsanlino.com, info@hotelsanlino.com).

$ Albergo Etruria is on Volterra’s main drag. They offer a good location, a peaceful rooftop garden, and 18 frilly rooms (RS%, family rooms, fans but no air-con, Via Matteotti 32, tel. 0588-87377, www.albergoetruria.it, info@albergoetruria.it, Paola, Daniele, and Sveva).

$ Albergo Nazionale, with 38 big and aging rooms, is simple, a little musty, popular with school groups, and steps from the bus stop. It’s a nicely located last resort if you have your heart set on sleeping in the old town (RS%, family rooms, elevator, Via dei Marchesi 11, tel. 0588-86284, www.hotelnazionale-volterra.it, info@hotelnazionale-volterra.it).

These accommodations are within a 5- to 20-minute walk of the city walls.

$$$ Park Hotel Le Fonti, a dull and steep 10-minute walk downhill from Porta all’Arco, can’t decide whether it’s a business hotel or a resort. The spacious, imposing building feels old and stately and has 64 modern, comfortable rooms, many with views. While generally overpriced, it can be a good value if you manage to snag a deal. In addition to the swimming pool, guests can use its small spa (pay more for a view or a balcony, air-con, elevator, on-site restaurant, wine bar, free parking, Via di Fontecorrenti 2, tel. 0588-85219, www.parkhotellefonti.com, info@parkhotellefonti.com).

$ La Primavera B&B feels like a British B&B transplanted to Tuscany. It’s a great value just a few minutes’ walk outside Porta Fiorentina (near the Roman Theater). Silvia rents five charming, neat-as-a-pin rooms that share a cutesy-country lounge. The house is set back from the road in a pleasant courtyard and garden to lounge in. With free parking and the shortest walk to the old town among my out-of-town listings, this is a handy option for drivers (RS%, fans but no air-con, Via Porta Diana 15, tel. 0588-87295, mobile 328-865-0390, www.affittacamere-laprimavera.com, info@affittacamere-laprimavera.com).

¢ Chiostro delle Monache, Volterra’s youth hostel, fills a wing of the restored Convent of San Girolamo with 68 beds in 23 rooms. It’s modern, spacious, and very institutional, with lots of services and a tranquil cloister. Unfortunately, it’s about a 20-minute hike out of town, in a boring area near deserted hospital buildings (private rooms available and include breakfast, family rooms, reception closed 13:00-15:00 and after 20:00, elevator, free parking, kids’ playroom; Via dell Teatro 4, look for hospital sign from main Volterra-San Gimignano road; tel. 0588-86613, www.ostellovolterra.it, info@ostellovolterra.it).

$ Hotel Foresteria, near Chiostro delle Monache and run by the same organization, has 35 big, utilitarian, new-feeling rooms with decent prices but the same location woes as the hostel; it’s worth considering for a family with a car and a tight budget (family rooms, air-con, elevator, restaurant, free parking, Borgo San Lazzaro, tel. 0588-80050, www.foresteriavolterra.it, info@foresteriavolterra.it).

$$ Podere Marcampo is an agriturismo set in the dramatic scenery of the calanche (cliffs) about two miles north of Volterra on the road to Pisa. Run by Genuino (owner of the recommended Ristorante Enoteca del Duca), his wife Ivana, and their English-speaking daughter Claudia, this peaceful spot has three dark but well-appointed rooms and three apartments, plus a swimming pool with panoramic views. Genuino produces his Sangiovese and award-winning Merlot on site and offers €20 wine tastings with five types of wine, cheese, homemade salumi, and grappa. Cooking classes at their restaurant in town are also available (apartments, breakfast included for Rick Steves readers, air-con, free self-service laundry, free parking, tel. 0588-85393, Claudia’s mobile 328-174-4605, www.agriturismo-marcampo.com, info@agriturismo-marcampo.com).

(See “Volterra” map, here.)

Menus feature a Volterran take on regional dishes. Zuppa alla Volterrana is a fresh vegetable-and-bread soup, similar to ribollita. Torta di ceci, also known as cecina, is a savory crêpe-like garbanzo-bean flatbread that’s served at pizzerie. Those with more adventurous palates dive into trippa (tripe stew, the traditional breakfast of the alabaster carvers). Fegatelli are meatballs made with liver.

$$$$ Ristorante Enoteca del Duca, serving well-presented and creative Tuscan cuisine, offers the best elegant meal in town. You can dine under a medieval arch with walls lined with wine bottles, in a sedate, high-ceilinged dining room (with an Etruscan statuette at each table), in their little enoteca (wine cellar), or in their terraced garden in summer. Chef Genuino, daughter Claudia, and the friendly staff take good care of diners. The fine wine list includes Genuino’s own highly regarded Merlot and Sangiovese. The spacious seating, dressy clientele, and calm atmosphere make this a good choice for a romantic splurge. Their €55 food-sampler fixed-price meal comes with a free glass of wine for diners with this book (Wed-Mon 12:30-15:00 & 19:30-22:00, closed Tue, near City Hall at Via di Castello 2, tel. 0588-81510, www.enoteca-delduca-ristorante.it).

$$ La Carabaccia is unique: It feels like a local family invited you over for a dinner of classic Tuscan comfort food that’s rarely seen on restaurant menus. They serve only two pastas and two secondi on any given day (listed on the chalkboard by the door), in addition to quality cheese-and-cold-cut plates. Committed to tradition, on Fridays they serve only fish. They also have fun, family-friendly outdoor seating on a traffic-free piazza (Tue-Sat 12:30-14:30 & 19:30-22:00, Sun 12:30-14:30, closed Mon, reservations smart, Piazza XX Settembre 4, tel. 0588-86239, Patrizia and her daughters Sara and Ilaria).

$$ Ristorante il Sacco Fiorentino is a family-run local favorite for traditional cuisine and seasonal specials. While mostly indoors, the restaurant has a few nice tables on a peaceful street (Thu-Tue 12:00-15:00 & 19:00-22:00, closed Wed, Via Giusto Turazza 13, tel. 0588-88537).

$$ Trattoria da Badò, a 10-minute hike out of town (along the main road toward San Gimignano, near the turnoff for the old hospital), is popular with a local crowd for its cucina tipica Volterrana. Giacomo and family offer a rustic atmosphere and serve food with no pretense—“the way you wish your mamma cooks.” Reserve before you go, as it’s often full, especially on weekends (Thu-Tue 12:30-14:30 & 19:30-22:00, closed Wed, Borgo San Lazzero 9, tel. 0588-80402).

$$ La Vecchia Lira, bright and cheery, is a classy self-serve eatery that’s a hit with locals as a quick and cheap lunch spot by day and a fancier restaurant at night (Fri-Wed 11:30-14:30 & 19:00-22:30, closed Thu, Via Matteotti 19, tel. 0588-86180, Lamberto and Massimo).

$$ Ristorante Ombra della Sera is another good fine-dining option. While they have a dressy interior, I’d eat here to be on the street and part of the passeggiata action (Tue-Sun 12:00-15:00 & 19:00-22:00, closed Mon and mid-Nov-mid-March, Via Gramsci 70, tel. 0588-86663, Massimo and Cinzia).

$$ Empathy Bistrot is a good bet for organic and vegetarian dishes. They also make creative cocktails and don’t close in the afternoon, making this an option at any hour. Choose between charming streetside tables or the modern, stony interior, where the glass floor hovers over an excavated Etruscan archaeological site (Fri-Wed 11:30-21:00, closed Thu, Via Porta All’Arco 11, tel. 0588-81531).

$$ Pizzeria La Mangiatoia is a fun and convivial place with a Tuscan-cowboy interior and picnic tables outside amid a family-friendly street scene. Enjoy pizzas, huge salads, and kebabs at a table or to go (Thu-Tue 12:00-23:00, closed Wed, Via Gramsci 35, tel. 0588-85695).

Side-by-Side Pizzerias: $ Ombra della Sera dishes out what local kids consider the best pizza in town (Tue-Sun 12:00-15:00 & 19:00-22:00, closed Mon and mid-Nov-mid-March, Via Guarnacci 16, tel. 0588-85274). $ Pizzeria Tavernetta, next door, has a romantically frescoed dining room upstairs for classier pizza eating (Wed-Mon 12:00-15:00 & 18:30-22:30, closed Tue, Via Guarnacci 14, tel. 0588-88155).

Picnic: You can assemble a picnic at the few alimentari around town and eat in the breezy archaeological park. The most convenient supermarket is Punto Simply at Via Gramsci 12 (Mon-Sat 7:30-13:00 & 16:00-20:00, Sun 8:30-13:00).

Gelato: Of the many ice-cream shops in the center, I’ve found L’Isola di Gusto to be reliably high-quality, with flavors limited to what’s in season (daily 11:00-late, closed Nov-Feb, Via Gramsci 3, cheery Giorgia will make you feel happy).

By Bus: In Volterra, buses come and go from Piazza Martiri della Libertà (buy tickets at the tobacco shop right on the piazza or on board for small extra charge). Most connections are with the C.T.T. bus company (www.pisa.cttnord.it) through Colle di Val d’Elsa (“koh-leh” for short), a workaday town in the valley (4/day Mon-Sat, 1/day Sun, 50 minutes); for Pisa, you’ll change in Pontedera or Saline di Volterra.

From Volterra, you can ride the bus to these destinations: Florence (4/day Mon-Sat, 1/day Sun, 2 hours, change in Colle di Val d’Elsa), Siena (4/day Mon-Sat, no buses on Sun, 2 hours, change in Colle di Val d’Elsa), San Gimignano (4/day Mon-Sat, 1/day Sun, 2 hours, change in Colle di Val d’Elsa, one connection also requires change in Poggibonsi), Pisa (9/day, 2 hours, change in Pontedera or Saline di Volterra).

By Train: The nearest train station is in Saline di Volterra, a 15-minute bus ride away (7/day, 2/day Sun); however, trains from Saline run only to the coast, not to the major bus destinations listed here. It’s better to take a bus from Volterra to Pontedera (CTT bus #500, 7/day, fewer on Sun, 1.5 hours), where you can catch a train to Florence, Pisa, or La Spezia (convenient for the Cinque Terre).

Private Transfer: For those with more money than time, or for travel on tricky Sundays and holidays, a private transfer to or from Volterra is the most efficient option. Roberto Bechi and his drivers can take up to eight people in their comfortable vans (€130 to Siena, €180 to Florence, for reservations call mobile 320-147-6590, Roberto’s mobile 328-425-5648, www.toursbyroberto.com, toursbyroberto@gmail.com).

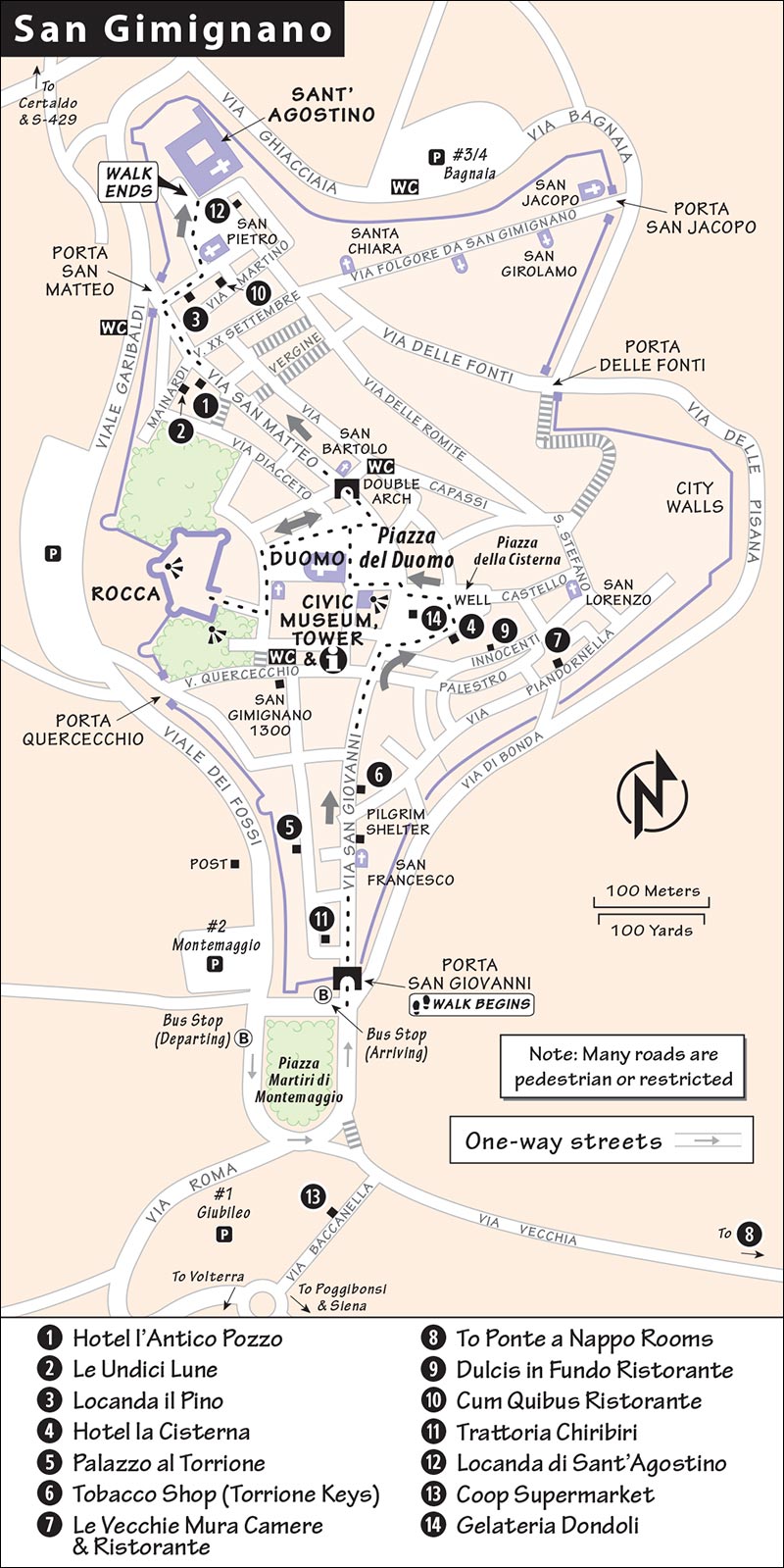

The epitome of a Tuscan hill town, with 14 medieval towers still standing (out of an original 72), San Gimignano (sahn jee-meen-YAH-noh) is a perfectly preserved tourist trap. There are no important interiors to sightsee, and the town feels greedy and packed with crass commercialism. The locals seem spoiled by the easy money of tourism, and most of the rustic is faux. But San Gimignano is so easy to reach and so visually striking that it remains a good stop, especially if you can sidestep some of the hordes. The town is an ideal place to go against the touristic flow—arrive late in the day, enjoy it at twilight, then take off in the morning before the deluge begins. (Or day-trip here from Volterra—a 30-minute drive away—and visit early or late.)

In the 13th century—back in the days of Romeo and Juliet—feuding noble families ran the hill towns. They’d periodically battle things out from the protection of their respective family towers. Pointy skylines like San Gimignano’s were the norm in medieval Tuscany.

San Gimignano’s cuisine is mostly what you might find in Siena—typical Tuscan home cooking. Cinghiale (cheeng-GAH-lay, boar) is served in almost every way: stews, soups, cutlets, and, my favorite, salami. The area is well-known for producing some of the best saffron in Italy; you’ll find the spice for sale in shops (fairly expensive) and as a flavoring in meals at finer restaurants. Although Tuscany is normally a red-wine region, the most famous Tuscan white wine comes from here: the inexpensive, light, and fruity Vernaccia di San Gimignano.

While the basic ▲▲▲ sight here is the town of San Gimignano itself (pop. 7,000, just 2,000 of whom live within the walls), there are a few worthwhile stops. The wall circles an amazingly preserved stony town, once on the Via Francigena pilgrimage route to Rome. The road, which cuts through the middle of San Gimignano, is named for St. Matthew in the north (Via San Matteo) of town and St. John in the south (Via San Giovanni). The town is centered on two delightful squares—Piazza del Duomo and Piazza della Cisterna—where you find the town well, City Hall, and cathedral (along with most of the tourists).

The helpful TI is in the old center on Piazza del Duomo (daily March-Oct 10:00-13:00 & 15:00-19:00, Nov-Feb 10:00-13:00 & 14:00-18:00, sells bus tickets to Siena and Florence, tel. 0577-940-008, www.sangimignano.com). They offer a two-hour minibus tour to a countryside winery (€30, April-Oct Tue and Thu at 17:00, book one day in advance).

The bus stops at the main town gate, Porta San Giovanni. There’s no baggage storage in town.

You can’t drive within the walled town; drive past the ZTL red circle and you’ll get socked with a big fine. Three numbered pay lots are a short walk outside the walls: The handiest is Parcheggio Montemaggio (P2), at the bottom of town near the bus stop, just outside Porta San Giovanni (€2/hour, €20/day). Least expensive is the lot below the roundabout and Coop supermarket, called Parcheggio Giubileo (P1; €1.50/hour, €6/day), a steeper hike into town. And at the north end of town, by Porta San Jacopo, is Parcheggio Bagnaia (P3/P4, €2/hour, €15/day). Note that some lots—including the one directly in front of Coop and the one just outside Porta San Matteo—are designated for locals and have a one-hour limit for tourists.

Market Day: Thursday is market day on Piazza del Duomo (8:00-13:00), but for local merchants, every day is a sales frenzy.

Services: A public WC is just off Piazza della Cisterna; you’ll also find WCs at the Rocca fortress, near San Bartolo church, just outside Porta San Matteo, and at the Parcheggio Bagnaia parking lot.

Shuttle Bus: A little electric shuttle bus does its laps about hourly all day from Porta San Giovanni to Piazza della Cisterna to Porta San Matteo. Route #1 runs back and forth through town; route #2—which runs only in summer—connects the three parking lots to the town center (€0.75 one-way, €1.50 all-day pass, buy ticket in advance at TI or tobacco shop, possible to buy all-day pass on bus). When pedestrian congestion in the town center is greatest (Sat afternoons, all day Sun, and July-Aug), the bus runs along the road skirting the outside of town.

(See “Gimignano” map, here.)

This quick self-guided walking tour takes you across town, from the bus stop at Porta San Giovanni through the town’s main squares to the Duomo, and on to the Sant’Agostino Church.

• Start at the Porta San Giovanni gate at the bottom (south) end of town.

San Gimignano lies about 25 miles from both Siena and Florence, a day’s trek for pilgrims en route to those cities, and on a naturally fortified hilltop that encouraged settlement. The town’s walls were built in the 13th century, and gates like this helped regulate who came and went. Today, modern posts keep out all but service and emergency vehicles. The small square just outside the gate features a memorial to the town’s WWII dead. Follow the pilgrims’ route (and flood of modern tourists) through the gate and up the main drag.

About 100 yards up, where the street widens, look right to see a pilgrims’ shelter (12th-century, Pisan Romanesque). The eight-pointed Maltese cross on the facade of the church indicates that it was built by the Knights of Malta, whose early mission (before they became a military unit) was to provide hospitality for pilgrims. It was one of 11 such shelters in town. Today, only the wall of the shelter remains, and the surviving interior of the church houses yet one more shop selling gifty edibles.

• Carry on past all manner of shops, up to the top of Via San Giovanni. Look up at the formidable inner wall, built 200 years before today’s outer wall. Just beyond that is the central Piazza della Cisterna. Sit on the steps of the well.

The piazza is named for the cistern that is served by the old well standing in the center of this square. A clever system of pipes drained rainwater from the nearby rooftops into the underground cistern. This square has been the center of the town since the ninth century. Turn in a slow circle and observe the commotion of rustic-yet-proud facades crowding in a tight huddle around the well. Imagine this square in pilgrimage times, lined by inns and taverns for the town’s guests. Now finger the grooves in the lip of the well and imagine generations of maids and children fetching water. Each Thursday morning, the square fills with a market—as it has for more than a thousand years.

• Notice San Gimignano’s famous towers.

Of the original 72 towers, only 14 survive (and one can be climbed—at the City Hall). Some of the original towers were just empty, chimney-like structures built to boost noble egos, while others were actually the forts of wealthy families.

Before effective city walls were developed, rich people needed to fortify their own homes. These towers provided a handy refuge when ruffians and rival city-states were sacking the town. If under attack, tower owners would set fire to the external wooden staircase, leaving the sole entrance unreachable a story up; inside, fleeing nobles pulled up behind them the ladders that connected each level, leaving invaders no way to reach the stronghold at the tower’s top. These towers became a standard part of medieval skylines. Even after town walls were built, the towers continued to rise—now to fortify noble families feuding within a town (Montague and Capulet-style).

In the 14th century, San Gimignano’s good times turned very bad. In the year 1300, about 13,000 people lived within the walls. Then, in 1348, a six-month plague decimated the population, leaving the once-mighty town with barely 4,000 survivors. Once fiercely independent, now crushed and demoralized, San Gimignano came under Florence’s control and was forced to tear down most of its towers. (The Banca CR Firenze building occupies the remains of one such toppled tower.) And, to add insult to injury, Florence redirected the vital trade route away from San Gimignano. The town never recovered, and poverty left it in a 14th-century architectural time warp. That well-preserved cityscape, ironically, is responsible for the town’s prosperity today.

• From the well, walk 30 yards uphill to the adjoining square with the cathedral.

Stand at the base of the stairs in front of the church. Since before there was gelato, people have lounged on these steps. Take a 360-degree spin clockwise: The cathedral’s 12th-century facade is plain-Jane Romanesque—finished even though it doesn’t look it. To the right, the two Salvucci Towers (a.k.a. the “Twin Towers”) date from the 13th century. Locals like to brag that the architect who designed New York City’s Twin Towers was inspired by these. The towers are empty shells, built by the wealthy Salvucci family simply to show off. At that time, no one was allowed a vanity tower higher than the City Hall’s 170 feet. So the Salvuccis built two 130-foot towers—totaling 260 feet of stony ego trip.

The stubby tower next to the Salvuccis’ is the Merchant’s Tower. Imagine this in use: ground-floor shop, warehouse upstairs (see the functional shipping door), living quarters, and finally the kitchen on the top (for fire-safety reasons). The holes in the walls held beams that supported wooden balconies and exterior staircases. The tower has heavy stone on the first floor, then cheaper and lighter brick for the upper stories.

Opposite the church stands the first City Hall, with its 170-foot tower, nicknamed “the bad news tower.” While the church got to ring its bells in good times, these bells were for wars and fires. The tower’s arched public space hosted a textile market back when cloth was the foundation of San Gimignano’s booming economy.

Next is the super-sized “new” City Hall with its 200-foot tower (the only one in town open to the public; for visiting info, see the Civic Museum and Tower listing, later). The climbing lion is the symbol of the city. The coats of arms of the city’s leading families have been ripped down or disfigured. In medieval times locals would have blamed witches or ghosts. For the last two centuries, they’ve blamed Napoleon instead.

Between the City Hall and the cathedral, a statue of St. Gimignano presides over all the hubbub. The fourth-century bishop protected the village from rampaging barbarians—and is now the city’s patron saint. (To enter the cathedral, walk under that statue.)

• You’ll also see the...

Inside San Gimignano’s Romanesque cathedral, Sienese Gothic art (14th century) lines the nave with parallel themes—Old Testament on the left and New Testament on the right. (For example, from back to front: Creation facing the Annunciation, the birth of Adam facing the Nativity, and—farther forward—the suffering of Job opposite the suffering of Jesus.) This is a classic use of art to teach. Study the fine Creation series (along the left side). Many scenes are portrayed with a 14th-century “slice of life” setting to help lay townspeople relate to Jesus—in the same way that many white Christians are more comfortable thinking of Jesus as Caucasian.

To the right of the altar, the St. Fina Chapel honors the devout, 13th-century local girl who brought forth many miracles on her death. Her tomb is beautifully frescoed with scenes from her life by Domenico Ghirlandaio (famed as Michelangelo’s teacher). The altar sits atop Fina’s skeleton, and its centerpiece is a reliquary that contains her skull (€4, includes dry audioguide; April-Oct Mon-Fri 10:00-19:30, Sat until 17:30, Sun 12:30-19:30; shorter hours off-season; buy ticket and enter from courtyard around left side).

• From the church, hike uphill (passing the church on your left) following signs to Rocca e Parco di Montestaffoli. Keep walking until you enter a peaceful hilltop park and olive grove, set within the shell of a 14th-century fortress the Medici of Florence built to protect this town from Siena.

On the far side, 33 steps take you to the top of a little tower (free) for the best views of San Gimignano’s skyline; the far end of town and the Sant’Agostino Church (where this walk ends); and a commanding 360-degree view of the Tuscan countryside. San Gimignano is surrounded by olives, grapes, cypress trees, and—in the Middle Ages—lots of wild dangers. Back then, farmers lived inside the walls and were thankful for the protection.

• Return to the bottom of Piazza del Duomo, turn left, and continue your walk, cutting under the double arch (from the town’s first wall). In around 1200, this defined the end of town. The Church of San Bartolo stood just outside the wall (on the right). The Maltese cross over the door indicates that it likely served as a hostel for pilgrims. As you continue down Via San Matteo, notice that the crowds have dropped by at least half. Enjoy the breathing room as you pass a fascinating array of stone facades from the 13th and 14th centuries—now a happy cancan of wine shops and galleries. Reaching the gateway at the end of town, follow signs to the right to reach...

This tranquil church, at the far end of town (built by the Augustinians who arrived in 1260), has fewer crowds and more soul. Behind the altar, a lovely fresco cycle by Benozzo Gozzoli (who painted the exquisite Chapel of the Magi in the Medici-Riccardi Palace in Florence) tells of the life of St. Augustine, a North African monk who preached simplicity (pay a few coins for light). The kind, English-speaking friars (often from Britain and the US) are happy to tell you about the frescoes and their way of life. Pace the peaceful cloister before heading back into the tourist mobs (free, April-Oct daily 9:00-12:00 & 15:00-17:00, shorter hours off-season; Sunday Mass in English at 11:00).

This small, entertaining museum, consisting of three unfurnished rooms, is inside the City Hall (Palazzo Comunale). The main reason to visit is to scale the tower, which offers sweeping views over San Gimignano and the countryside.

Cost and Hours: €9 includes museum and tower; daily 10:00-19:30, Oct-March 11:00-17:30, audioguide-€2, Piazza del Duomo, tel. 0577-990-312, www.sangimignanomusei.it.

Visiting the Museum: You’ll enter the complex through a delightful stony courtyard (to the left as you face the Duomo). Climb up to the loggia to buy your ticket.

The main room (across from the ticket desk), called the Sala di Consiglio (a.k.a. Dante Hall, recalling his visit in 1300), is covered in festive frescoes, including the Maestà by Lippo Memmi (from 1317). This virtual copy of Simone Martini’s Maestà in Siena proves that Memmi didn’t have quite the same talent as his famous brother-in-law. The art gives you a peek at how people dressed, lived, worked, and warred back in the 14th century.

Upstairs, the Pinacoteca displays a classy little painting collection of mostly altarpieces. The highlight is a 1422 altarpiece by Taddeo di Bartolo honoring St. Gimignano (far end of last room). You can see the saint with the town—bristling with towers—in his hands, surrounded by events from his life.

Before going back downstairs, be sure to stop by the Mayor’s Room (Camera del Podestà, across the stairwell from the Pinacoteca). Frescoed in 1310, it offers an intimate and candid peek into the 14th century. As you enter, look right up in the corner to find a young man ready to experience the world. He hits his parents up for a bag of money and is on his way. Suddenly (above the window), he’s in trouble, entrapped by two prostitutes, who lead him into a tent where he loses his money, is turned out, and is beaten. Above the door, from left to right, you see a parade of better choices: marriage, the cradle of love, the bride led to the groom’s house, and newlyweds bathing together and retiring happily to their bed.

The highlight for most visitors is a chance to climb the Tower (Torre Grossa, entrance halfway down the stairs from the Pinacoteca). The city’s tallest tower, 200 feet and 218 steps up, rewards those who climb it with a commanding view. See if you can count the town’s 14 towers. It’s a sturdy, modern staircase most of the way, but the last stretch is a steep, ladder-like climb.

Artists and brothers Michelangelo and Raffaello Rubino share an interesting attraction in their workshop: a painstakingly rendered 1:100 scale clay model of San Gimignano at the turn of the 14th century. Step through a shop selling their art to enjoy the model. You can see the 72 original “tower houses,” and marvel at how unchanged the street plan remains today. You’ll peek into cross-sections of buildings, view scenes of medieval life both within and outside the city walls, and watch a video about the making of the model.

Cost and Hours: Free, daily 10:00-18:00, Dec-April until 17:00, on a quiet street a block over from the main square at Via Costarella 3, mobile 327-439-5165, www.sangimignano1300.com.

Although the town is a zoo during the daytime, locals outnumber tourists when evening comes, and San Gimignano becomes mellow and enjoyable.

If arriving by bus, save yourself a crosstown walk to these accommodations by asking for the Porta San Matteo stop (rather than the main stop near Porta San Giovanni). Drivers can park at the less-crowded Bagnaia lots (P3 and P4), and walk around to Porta San Matteo.

$$$ Hotel l’Antico Pozzo is an elegantly restored, 15th-century townhouse with 18 tranquil, comfortable rooms, a peaceful interior courtyard terrace, and an elite air (RS%—use code “RICK,” air-con, elevator, Via San Matteo 87, tel. 0577-942-014, www.anticopozzo.com, info@anticopozzo.com; Emanuele, Elisabetta, and Mariangela).

$$ Le Undici Lune (“The 11 Moons”) is situated in a tight but characteristic circa-1300 townhouse with steep stairs at the tranquil end of town. Its three rooms and one apartment have been tastefully decorated with modern flair by Gabriele (RS%, air-con, Via Mainardi 9, mobile 389-236-8174, www.leundicilune.com, leundicilune@gmail.com).

$ Locanda il Pino has just seven rooms and a big living room. It’s dank but clean and quiet. Run by English-speaking Elena and her family, it sits above their elegant restaurant at the quiet end of town, just inside Porta San Matteo (breakfast extra, fans, Via Cellolese 4, tel. 0577-940-218, www.locandailpino.it, locandailpino@gmail.com).

$$ Hotel la Cisterna, right on Piazza della Cisterna, feels old and stately. Its 48 rooms range from old-fashioned to contemporary, and some have panoramic view terraces—one of which served as the viewpoint for a scene in the film Tea with Mussolini (RS%, air-con, elevator, good restaurant with great view, closed Jan-Feb, Piazza della Cisterna 23, tel. 0577-940-328, www.hotelcisterna.it, info@hotelcisterna.it, Alessio and Paola).

$$ Palazzo al Torrione, on an untrampled side street just inside Porta San Giovanni, is quiet and handy. Despite the smoky reception area, this place is generally better than most local hotels. Their 10 modern rooms, some with countryside views, are spacious and tastefully appointed (RS%, family rooms, breakfast extra, air-con, pay parking, inside and left of gate at Via Berignano 76; operated from tobacco shop 2 blocks away, on the main drag at Via San Giovanni 59; tel. 0577-940-480, mobile 338-938-1656, www.palazzoaltorrione.com, palazzoaltorrione@palazzoaltorrione.com, Vanna and Francesco).

$ Le Vecchie Mura Camere offers three good rooms above their recommended restaurant along a rustic lane, clinging just below the main square (no breakfast, air-con, Via Piandornella 15, tel. 0577-940-270, www.vecchiemura.it, info@vecchiemura.it, Bagnai family).

$$ Ponte a Nappo, run by enterprising Carla Rossi and her English-speaking sons Francesco and Andrea, has six basic rooms and two apartments in a kid-friendly farmhouse boasting fine San Gimignano views. Located a mile below town, it can be reached by foot in about 20 minutes if you don’t have a car. A picnic dinner lounging on their comfy garden furniture next to the big swimming pool as the sun sets is good Tuscan living (RS%—use code “RickSteves,” air-con, free parking, tel. 0577-907-282, mobile 349-882-1565, www.accommodation-sangimignano.com, info@rossicarla.it). About 100 yards below the monument square at Porta San Giovanni, find tiny Via Baccanella/Via Vecchia and drive downhill. They also rent a dozen rooms and apartments in town.

(See “Gimignano” map, here.)

My first two listings cling to quiet, rustic lanes overlooking the Tuscan hills (yet just a few steps off the main street); the rest are buried deep in the old center.

$$$ Dulcis in Fundo Ristorante, small and family-run, proudly serves modest portions of “revisited” Tuscan cuisine (with a modern twist and gourmet presentation) in a jazzy ambience. This enlightened place uses top-quality ingredients, many of which come from their own farm. They also offer vegetarian and gluten-free options (Thu-Tue 12:30-14:30 & 19:15-21:45, closed Wed and Nov-Feb, Vicolo degli Innocenti 21, tel. 0577-941-919, Roberto and Cristina).

$$ Le Vecchie Mura Ristorante is welcoming, with good service, great prices, tasty if unexceptional home cooking, and the ultimate view. It’s romantic indoors or out. They have a dressy, modern interior where you can dine with a view of the busy stainless-steel kitchen under rustic vaults, but the main reason to come is for the incredible, cliffside garden terrace. Cliffside tables are worth reserving in advance by calling or dropping by: Ask for “front view” (open only for dinner 18:00-22:00, closed Tue, Via Piandornella 15, tel. 0577-940-270, Bagnai family).

$$$ Cum Quibus (“In Company”), tucked away near Porta San Matteo, has a small dining room with soft music, beamed ceilings, modern touches, and a sophisticated vibe; it also offers al fresco tables in its interior patio. Lorenzo and Simona produce tasty and creative Tuscan cuisine (Wed-Mon 12:30-14:30 & 19:00-22:00, closed Tue, reservations advised, Via San Martino 17, tel. 0577-943-199).

$ Trattoria Chiribiri, just inside Porta San Giovanni on the left, serves homemade pastas and desserts at good prices. While its petite size and tight seating make it hot in the summer, it’s a good budget option—and as such, it’s in all the guidebooks (daily 11:00-23:00, Piazza della Madonna 1, tel. 0577-941-948, Roberto and Maurizio).

$$ Locanda di Sant’Agostino spills out onto the peaceful square, facing Sant’Agostino Church. It’s homey and cheerful, serving lunch and dinner daily—big portions of basic food in a restful setting. Dripping with wheat stalks and atmosphere on the inside, it has shady on-the-square seating outside (daily 11:00-23:00, closed Wed off-season, closed Jan-Feb, Piazza Sant’Agostino 15, tel. 0577-943-141, Genziana and sons).

Near Porto San Matteo: Just inside Porta San Matteo is a variety of handy and inviting good-value restaurants, bars, cafés, and gelaterie. Eateries need to work harder here at the nontouristy end of town.

Picnics: The big, modern Coop supermarket sells all you need for a nice spread (Mon-Sat 8:30-20:00, closed Sun, at parking lot below Porta San Giovanni). Or browse the little shops guarded by boar heads within the town walls; they sell pricey boar meat (cinghiale). Pick up 100 grams (about a quarter pound) of boar, cheese, bread, and wine and enjoy a picnic in the garden at the Rocca or the park outside Porta San Giovanni.

Gelato: To cap the evening and sweeten your late-night city stroll, stop by Gelateria Dondoli on Piazza della Cisterna (at #4). Gelato maker Sergio was a member of the Italian team that won the official Gelato World Cup—and his gelato really is a cut above. He’s usually near the front door greeting customers—ask what new flavors he’s invented recently (tel. 0577-942-244, www.gelateriadondoli.com, sergio@gelateriadondoli.com, Dondoli family). Charismatic Sergio also offers hands-on gelato making classes in his kitchen down the street.

Bus tickets are sold at the bar just inside the town gate or at the TI. Many connections require a change at Poggibonsi (poh-jee-BOHN-see), which is also the nearest train station.

From San Gimignano by Bus to: Florence (hourly, fewer on Sun, 1.5-2 hours, change in Poggibonsi), Siena (8/day direct, on Sun must change in Poggibonsi, 1.5 hours), Volterra (4/day Mon-Sat; 1/day Sun—in the late afternoon and usually crowded—with no return to San Gimignano; 2 hours, change in Colle di Val d’Elsa, one connection also requires change in Poggibonsi). Note that the bus connection to Volterra is four times as long as the drive; if you’re desperate to get there faster, you can pay about €70 for a taxi.

By Car: San Gimignano is an easy 45-minute drive from Florence (take the A-1 exit marked Firenze Imprugneta, then a right past tollbooth following Siena per 4 corsie sign; exit the freeway at Poggibonsi Nord). From San Gimignano, it’s a scenic and windy half-hour drive to Volterra.