3 Post-Democracy and the Politics of Inequality: Explaining Policy Responses to the Financial Crisis and the Great Recession

JOHN PETERS

Theoretically, democracy offers citizens opportunities to participate in shaping the agenda of public life, and ensures that public policies provide accountability and fairness in the distribution of adequate jobs and disposable income. But over the past three decades, not only have the economic forces of globalization created widening inequalities, but many governments have appeared to slip under the control of powerful economic interests far more hostile to regulation, taxes, and the mixed economy than in the post-war era, and retreated from efforts to improve income redistribution and jobs. In the wake of the Financial Crisis (2008–9), these trends have often worsened.

Despite unprecedented bailouts of financial institutions and wide public debate on the failures of market economies, governments in Canada and other rich world democracies returned to the neoliberal policy models that prompted many of the key problems that caused the crisis – tax cuts and deregulation, ‘“flexibility” policies that lowered labour costs and aggregate demand, and limited regulation of the financial sector. Then, contrary to popular demands for redistribution and employment, public officials began to advance policies for an even “leaner” and less interventionist state, implementing a series of austerity policies that included reductions in public employment and cutbacks to services. To many commentators, such as the Nobel Prize–winning economists Joseph Stiglitz and Jeffrey Sachs, such developments have shown that there are very real limits to the extent to which inequality can be eliminated or improved in rich world democracies (Sachs 2012; Stiglitz 2010).

Understanding why such persistent inequalities remain and why government responses to rising inequality have been inadequate is now at the heart of a number of academic, policy, and political debates on income inequality. This chapter draws on the recent work of Colin Crouch about “post-democracy” to explore the politics of inequality in North America and Western Europe after the Financial Crisis of 2008–9. Comparing tax and credit policies to job- and income-related programs, as well as to labour market deregulation policies, the argument is made that governments affected the distribution of market income in immediate and substantial ways. On the one hand, policymakers provided massive bank bailouts and aid to the financial sector in order to uphold global financialization and the upward distribution of income, as well as upheld favourable tax policies for business and liberalized capital and credit markets. On the other, government officials backed corporate plans for wage and job concessions while forwarding efforts at labour market deregulation and the erosion of employment protection. On the basis of literature exploring the dynamics of “post-democracy” in advanced industrial countries, the chapter claims that global and domestic power imbalances between corporate interests and those of other organized groups explain these outcomes.

Governments, it is argued, gave primacy to the goal of improving the business environment because powerful economic interests were able to influence policy and because public officials had a structural dependence on the business and financial community for economic success. By contrast, unions and labour market “outsiders” (immigrants, the unskilled, and the precariously employed) bore the brunt of the economic downturn, and had little effect on policymaking. This response was in line with earlier developments over the past three decades, where governments forwarded neoliberal policies that restructured markets and labour management relations in ways that created new profit opportunities for capital.

Beginning in the 1970s – in reaction to economic slowdowns, external challenges, and the globalization of business and finance – governments consistently introduced a number of pro-business neoliberal reforms. These included states acting forcefully to make their labour markets more competitive. They also included public officials deregulating finance and institutionalizing free trade and international investment agreements in order to stimulate macroeconomic demand and improve the global business environment for multinational corporations and finance. Across advanced industrial countries, such changes to policy were introduced incrementally or were enacted in a more sweeping fashion in response to economic shocks.

Since the Financial Crisis, national policymakers have reacted to the latest economic downturn in a more comprehensive fashion to re-establish the conditions for business growth and profitability by advancing policy models of public sector austerity and structural labour market reform. Such policy measures, the chapter concludes, far from questioning finance and neoliberal policy models, have done much to reinforce them, deepening the extent and intensity of income inequality and low-wage work across advanced industrial economies. The chapter begins first by reviewing recent trends in income inequality, declining wages, and low-wage work before and after the crisis.

Market Income Inequality and Low-Wage Work

During the past two decades, income inequality and low-wage work have increased significantly in advanced industrial countries, most notably in Canada and the United States but also across Western Europe as well (OECD 2008, 2011a). The Financial Crisis of 2008–9 has only exacerbated these trends. Today, throughout the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, 40–53 per cent of workers are employed in occupations that are strongly affected by unemployment and/or atypical employment (Emmenger et al. 2011). Across OECD countries, the share of atypical employment in the overall workforce (part-time and fixed-term employment) has grown from an average of around 10 per cent to 25–35 per cent (Gautie and Schmitt 2010). Since the Financial Crisis, these negative changes have often only worsened in the majority of rich world democracies.

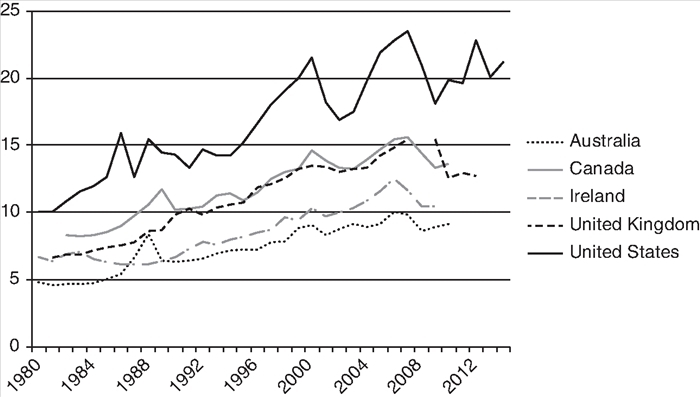

At the very top, over the past generation, the share of top-income recipients in total earned income has soared from approximately 6 per cent in 1974 to more than 10 per cent in 2010 (Atkinson and Piketty 2007; Saez and Veall 2005). If capital gains such as investment and dividend income are included, the share of income that the top 1 per cent of earners have received has gone from just over 9 per cent to 17 per cent (Atkinson and Piketty 2010). The global crisis in 2008 did bring about a fall in top income shares in many countries. But this fall appears to have been temporary (see figure 3.1). This reversal was most marked in the United States, where the share of the richest 1 per cent fell by 12 per cent in 2009, but rose by more than 15 per cent in 2011 and quickly surpassed the top income share rate of 2007 (OECD 2014). But rich households have recovered exceedingly well in a number of other countries including Sweden and Denmark, where the top 1 per cent income share fell only briefly in 2009, before rapidly increasing to approximately 7 per cent in both countries in 2010–11.

Figure 3.1. Trends in Top Income* Shares in the English-Speaking Countries

*Income refers to pre-tax incomes as well as capital gains.

Source: World Wealth and Income Database – WID.

As Thomas Piketty (2014) and others have recently argued, a key reason for this rapid rise in income inequality – and its recovery after the Financial Crisis – was the growing share of economic growth captured by the rich both before and after the crisis. Over the period 1976–2007, the average incomes of the top 1 per cent earners grew at a rapid rate as they secured the majority of all income and economic growth (OECD 2011a). Across a number of advanced industrial economies over this period, more than half of many countries’ economic gains went to the richest 10 per cent (OECD 2014) – the United States, Canada, and Great Britain had the greatest disparities in income distribution, the Nordic countries and the Netherlands the least. But in terms of income captured by the top 1 per cent of earners, the richest individuals in the United States accrued more than 47 per cent of all economic growth over this thirty-year period; in Canada, the richest received more than 37 per cent (ibid.). In other countries, the trend of increased concentration of income at the top was less marked but still significant (OECD 2011a, 2014). In Continental Europe, for example, the slow and steady rise in income going to the top 10 per cent of earners reached 35 per cent in 2010 as CEOs, financial specialists, and managers appropriated ever greater gains (Piketty and Saez 2014).

But in the wake of the Financial Crisis, the key reason for rising market income inequality at the top was firms’ use of cash holding to invest in bonds, stocks, and money markets, which boosted corporate returns and executive compensation but did little to spur new investment (Dumenil and Lévy 2011). Cash holdings increased markedly in Europe following the global crisis, accompanied by a considerable fall-off in investment across firms of all sizes (ILO 2012). In the United States, the share of cash holdings in total assets in medium-sized firms increased from around 5.2 per cent in 2006 to around 6.2 per cent after the crisis, while in larger firms it rose from 4.2 per cent in 2006 to 5.3 per cent in 2010. At the same time, despite the decline of nominal interest rates to historic lows, firm investment in capital goods fell to its lowest level in the wake of the financial crisis (Brufman, Martinez, Pérez Artica 2013). By contrast, investment in stock and money markets soared, especially in emerging markets, leading to increasing fees, equity returns, and wealth returns for top income earners (UNCTAD 2012). Buoyed by public injections of trillions of dollars into financial markets, stock and money market indexes reached new heights, stimulating financial gains for top income earners. The result has been rising top income shares since the crisis.

But equally important for increasing market income inequality has been the failure of incomes to grow for the majority of low and middle-class income earners. Across the rich world democracies, the labour share of income declined in relation to the capital share (OECD 2012). The wage share in the business sector demonstrates this best, with recent OECD data showing steady deterioration over the past three decades. In the 1970s and early 1980s, wage share of income reached highs of 89 per cent in Sweden and Austria, and the peak average for the thirteen countries reached 78 per cent (see figure 3.2). Since then, the wage share in the business sector has steadily fallen as income from profits, stocks, shares, and rents have risen. In 1990, wage share had fallen to 71 per cent on average. In 2005, it fell further to 63 per cent. For the thirteen advanced industrial countries surveyed in figure 3.2, the average decline in labour share was 10.6 per cent, with the steepest declines seen in the Nordic countries.

Figure 3.2. The Decline in Wage Share* (Labour Share of National Income – Business Sector)

*Wage share is defined as total labour compensation share in the national income generated by the business sector.

Note: Averages and median based on (Nordic) Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden; (Continental) Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands; (liberal market economies) Canada, Great Britain, and the United States.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook, custom request.

The decline in wage share contributed strongly to the rise in household income inequality across the OECD, as the majority of households had little wealth, and the majority of household income – typically more than 80 per cent – was derived from labour income (Salverda and Haas 2014). In general, across the thirteen OECD countries surveyed here, a 1 per cent decline in wage share correlated with a 0.7 per cent rise in the Gini coefficient for market income 1995–2005, a number that could be even higher if all countries removed the gains of the top 1 per cent income earners that skew wage share data (OECD 2012, chap 3). Moreover, the OECD estimates that the major decline of the wage share was accounted for by within-industry developments and declines in real wages – unrelated to structural shifts away from labour-intensive and higher-paying industries within countries (OECD 2012, 120–2). Declines in wage share were also strongly correlated with globalization and the decline in the ability of workers’ collective bargaining institutions to counter employer pressures for wage reductions, a situation that led to the growth in wages lagging productivity in the majority of rich world democracies, regardless of skills or labour relations (ILO 2013).

Across the OECD, this decline in wages relative to income growth was part of another common trend: “job polarization,” flat or falling incomes for the majority of middle-income earners and the loss of good jobs. Examining changes to the ratio of median to average income, the income of middle-class earners fell in the bulk of rich world democracies (see figure 3.2). Overall, the decline in the ratio of median to average income was 2 per cent, with the ratio falling to 88 per cent in the mid-2000s as the growth rate of low-paying jobs surpassed that of high-paying jobs, and intermediate-paying jobs either disappeared or changed little (Goos, Manning, and Salomons 2009). Sweden and Denmark did witness some improvement in wages in the mid-2000s, but this had little to do with differences in educational or skill requirements. As Goos, Manning, and Salomons (2009) as well as the OECD (2012) have confirmed, the share of the low-educated fell throughout the rich world economies, while the percentage of workers with upper education remained stable. Instead, the decline in intermediate occupations was due to how educated workers – many overqualified – were increasingly ending up in low-pay jobs and displacing workers with lower skills (Kalleberg 2011).

Figure 3.3. Ratio of Mean-to-Median Income, Mid-1970s to Mid-2000s

Source: OECD 2008. Averages and median eleven countries based on (Nordic) Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden; (Continental) France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands; (liberal market economies) Canada, Great Britain, and the United States.

One of the main reasons for declines in annual median income was that firms were rapidly expanding their use of low-wage work and non-standard employment. Calculating those in full-time employment earning less than two-thirds of the median wage, as well as shares of temporary and part-time employment, analysts have shown how all advanced industrial countries increasingly came to rely on what is now called “cheap labour” (Gautie and Schmitt 2010; King and Rueda 2008). In the aftermath of the Financial Crisis these trends continued. As table 3.1 shows, throughout North America and Western Europe the total number of employees in full-time low-wage work climbed from 14 per cent of the labour force to more than 17 per cent, irrespective of bargaining coverage, skills, or economic competitiveness (1990–2009/10) (see also ibid.). Western European countries such as Germany (the major European exporter) saw the most rapid increases.

Table 3.1. Inequality and Low-Wage Work

Low-pay ratios* |

D9/D1 ratios** |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

2001–9 |

2011 |

2001–9 |

2011 |

|

Austria |

14.5 |

16.4 |

3.1 |

3.3 |

Belgium |

12.1 |

12.7 |

2.8 |

2.8 |

Canada |

22.1 |

20.3 |

3.7 |

3.8 |

Denmark |

11.1 |

16.7 |

2.6 |

2.7 |

Finland |

4.6 |

9.3 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

Germany |

19.2 |

21.2 |

3.2 |

3.3 |

Netherlands |

14.3 |

17.0 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

Sweden |

6.2 |

6.2 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

United Kingdom |

20.6 |

20.6 |

3.5 |

3.6 |

United States |

23.8 |

25.2 |

4.8 |

5.2 |

Median |

14.4 |

17.0 |

3.0 |

3.3 |

* Low-pay ratios are defined as the percentage of full-time workers earning two-thirds or less of the gross hourly median wage.

** D9/D1 ratios are comparisons of the wage or salary earned by individuals at the ninetieth percentile (those earning more than 90 per cent of other workers) compared to the earnings of workers at the lowest tenth percentile.

Sources: ILO Global Wage Report 2010/11 OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics online.

But in looking at changes over time, one key overall trend before and after the crisis was increasing low-pay, full-time employment. While the increase in low pay was relatively small in the United Kingdom, increases were substantially greater in many others like Denmark, Finland, Germany, and the United States, indicating that full-time low-wage earners lost ground to median wage-earners. The global recession worsened the situation for many low-paid workers, especially young workers, women, and immigrants, as they were among the first to experience layoffs or be displaced by workers with more seniority and education (ILO 2011a). These trends contributed then to the widening gap between high-wage/high-skill workers and those in low-wage and low-skill occupations, as the D9/D1 ratios across rich world democracies also increased on average from a ratio of 3 to 3.3 in 2011 (see table 3.1)

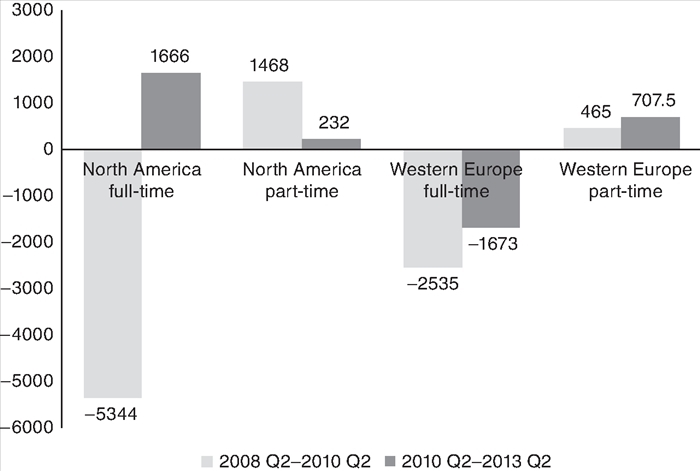

Another reason for the decline in wages was the growth of non-standard employment. It is well established that the majority of part-time and temporary jobs are remunerated at a rate below average wages (OECD 2012, 2011a). After 2008, net job growth has been primarily in part-time jobs, affecting earnings and annual incomes (Huwart and Verdier 2013). Employers who have sought to offset investment uncertainty have responded by increasing the flexibility of their workforces, driving the rise of non-standard employments (Milberg and Winkler 2013). Across Western Europe, full-time jobs fell annually by more than 2.5 million between 2008 and 2010 (see figure 3.4). But part-time jobs grew annually by 465,000 as employers replaced full-time workers with part-time. By contrast, in North America, the layoffs were far steeper between 2008 and 2010, as North America lost more than 8 million jobs. However, full-time employment began to pick up in 2012 while part-time employment continued to grow in both Canada and the United States to more than 23 per cent of all jobs.

Figure 3.4. Job Destruction and Creation in North America and Western Europe, Annual Averages, by Working Time, 2008–13 (000s)

Sources: ETUI 2014; OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics online.

A number of current comparative political economy theories suggest that variations in wage dispersion and employment are shaped by growth in industry sectors, skills, the strength of collective bargaining, and partisan politics (Pontusson 2005; Rueda 2008; Thelen 2014). But rising non-standard employment and increasing wage and income inequality among full-time workers throughout the different models of capitalism make such claims questionable. Certainly women, young workers, immigrants, and ethnic minorities found themselves relegated to low-wage work and non-standard employment, often characterized by low pay, little job security, and few opportunities for advancement (OECD 2011a). But non-standard contracts accounted for a large share of newly created jobs for all workers, and workers in low-skill service jobs experienced the largest variation in pay, job security, and benefits across North America and Western Europe (OECD 2012).

In developed economies, the OECD estimates that temporary contracts grew annually by 15–20 per cent, almost ten times the overall rate of employment growth over the period 1990–2005, even in manufacturing and public sectors – areas traditionally seen as having higher-quality jobs. After the crisis, part-time work increased considerably in both North America and Western Europe, indicating that employers were far more likely to lay off full-time workers, and were also more likely to begin rehiring by converting former full-time positions into part-time ones (OECD 2011b). These employer strategies affected hourly and annual earnings, as well as increasing earnings inequality across national economies.

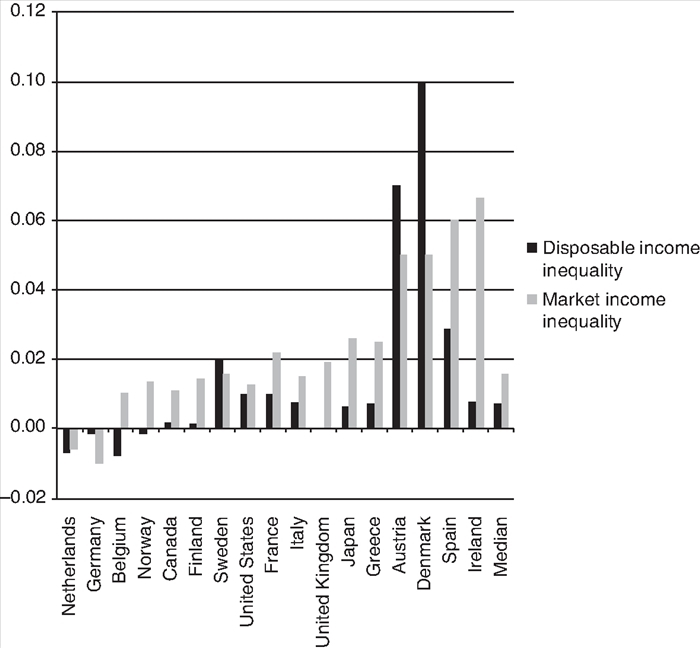

Between 2007 and 2011, market income inequality widened considerably, rising by nearly 2 percentage points in seventeen OECD countries (see figure 3.5). The increase was especially notable in countries most affected by the collapse of banks, construction, and housing industries such as Ireland and Spain, where unemployment soared with the global slowdown. But in these and many other countries, the rising number of unemployed, the decrease in earnings, and the slowdown in growth contributed to rising incoming inequality. Interestingly, income inequality rose most rapidly in Denmark and Austria. Only Germany and its two neighbouring economies closely tied to its manufacturing and export markets – Belgium and the Netherlands – saw declines in market and disposable income inequality as high incomes fell more than median incomes across their economies. It appears these jobs and income trends will continue, for after employment gains in 2012, unemployment and non-participation in labour markets have risen again, while the numbers of those in involuntary part-time and temporary employment have grown. This suggests that employment levels, job quality, and income inequality will remain problems for a number of countries in the short and medium term.

Figure 3.5. Change in the Gini Coefficient* of Market and Disposable Incomes, 2007 and 2011 (%)

*Gini coefficient measures the extent to which the distribution of income among individuals deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. A Gini index of 0 represents perfect equality, an index of 100 implies perfect inequality. Disposable income inequality measures inequality after tax and transfers.

Source: OECD Income Distribution Database Online.

Global Firms and Inequality in the Wake of the Financial Crisis

What accounts for the continuing rise in inequality after the Financial Crisis? Why did firms continue to expand the flexibility of their workforces? And why did governments continue to support policies that lowered labour and social costs rather than enhance employment? One key to explaining the rise in inequality was the unbalanced policy responses across advanced industrial economies. In size and scope, government support of the financial sector through a loan guarantees, purchase of bad debt, recapitalization of banks, and guarantees on bank liabilities far exceeded social program spending in many countries. In the United Kingdom, Belgium, and the Netherlands, direct state aid to the financial sector totalled more than 25 per cent of GDP, and in Ireland totalled more than twice its GDP (Grossman and Woll 2013). The majority of government measures were short-term and there were few structural reforms imposed on the financial sector. Between 2008 and 2011, it is estimated that the United States committed $12.6 trillion in government assistance to the financial sector, and more than $4 trillion with the Federal Reserve purchasing mortgage-backed and agency security as well as other long-term securities – or approximately 32 per cent of GDP (Atkinson, Luttrell, and Rosenblum 2013). In Europe, public support for the financial sector is estimated to have been equivalent to 37 per cent of EU GDP (European Commission 2012).

In contrast, despite making commitments to “fiscal” stimulus and support for growth and employment, for the majority of governments, tax cuts were the key focus of the packages intended to keep individuals spending even if unemployed or working part-time. Together, it was estimated that fiscal stimulus packages across the largest rich world economies would total 3.5 per cent of GDP (OECD 2009). Tax cuts on average contributed two-thirds of aggregate fiscal stimulus; labour market measures such as unemployment insurance and short-time work schemes less than 15 per cent (ILO 2011b). However, despite the fact that tax cuts are known to be less redistributive than spending and program increases, governments more readily adopted these measures than spending increases that had been more widely used during previous economic recessions (see Cohen, chapter 4; Pontusson and Raess 2012). Assessments of the tax-cut led packages showed they had little stimulus effect, while significantly worsening the budgetary position of governments. The economic and political weight of the banking sector on macroeconomic conditions and on public officials provides one suggestive explanation for these responses, and why – despite causing the Financial Crisis – rescue packages were designed to save finance at the cost of other interests and priorities.

But of equal importance in explaining the ongoing changes to employment and income distribution were global corporate strategies and multi-national corporations operational capacities. In the wake of the Financial Crisis, firms immediately withheld foreign direct investment from the developed countries, but by 2009 began to increase it towards non-OECD countries, and by 2013 cross-border acquisitions and large retained earnings in foreign affiliates in non-OECD countries were central drivers of global foreign direct investment growth (Economist Intelligence Unit 2014). Another key corporate strategy in response to the slowdown in growth and increased economic uncertainty was to lay off workers and then shift to more flexible and non-standard employment contracts. A third MNC tack was to significantly reduce export and inter-firm trade volumes along their global value chains, resulting in declines in trade and employment in developed and emerging economies alike.

Such corporate strategies were unique in the response to economic shocks. They also had significantly negative impacts on the labour markets of advanced industrial countries. In contrast to previous crises and recessions with comparable declines in GDP growth, what makes such corporate strategies notable in response to the Financial Crisis of 2008–9 was the ability of firms to use layoffs, and short-time work schemes in Western Europe, as a means of adjustment (Pontusson and Raess 2012). In the mid-1970s and early 1980s, changes in the unemployment rate were relatively modest, given the size of the decline in GDP. But from 2008 to 2010, in countries such as the United States, Greece, Spain, and Italy – as well as across the EU-28 – unemployment rose by more than 4 per cent at a minimum and more than 15 per cent at a maximum. These figures would be even higher if “discouraged” workers who have ceased looking for work were included in unemployment rates (ETUI 2014). Jonas Pontusson and Damien Raess (2012) have argued this “disproportionate” increase was due to weaker unions and more flexible labour markets that provided firms with greater opportunities to lay off workers and adjust working hours.

However, an equally likely explanation was the capacity of MNCs to adjust employment and working hours with little regard for domestic consequences. Moreover, unlike in the past, when governments could more easily regulate or press firms for employment-generating investments, governments now face global competition and the integrated production markets of global MNCs in the wake of the Financial Crisis. As such, governments quickly accommodated firm demands by lowering the costs for firms to restructure as well as reducing long-term labour costs (and labour-related social costs) to ensure global competitiveness. This suggests that rather than simply a case of policy deregulation as the reason for higher unemployment, it was the new global powers of business and the reliance of governments on MNCs for employment that explain policymakers’ adoption of business-oriented structural reforms in the wake of the crisis. Where in the past firms were restricted by a range of trade, labour regulations, and “national champion” industrial goals, after the economic downturn of 2008–9, individual giant firms set their own priorities with little reference to international or national authorities, and did so deliberately to lower costs.

Such an explanation suggests significant transformation to political economic power across advanced industrial economies. As recent critical literatures have highlighted, the rise of finance and global MNCs has challenged the balance between government and business, and now there are concerns that neither pluralism nor neo-corporatism can prevent the increasingly skewed influence of business on policy (Crouch 2006, 2011; Streeck 2014). Increasingly it is argued that it is necessary to reconceptualize large firms and finance as political entities. This is because policy rather than electoral victory is the grand prize of political conflict, and the main competitors are not, for the most part, individual voters; rather, the main combatants today are organized groups of business and labour. Business organizations wield real clout in daily political life through advocacy campaigns and lobbying, fundraising, and the development of policy and legal expertise (Horn 2012; Streeck and Visser 2006). High concentrations of wealth are also easily converted into political influence through political financing and global regulatory agencies (Moran 2009; Wilks 2013).

Furthermore, the size and influence of MNCs in national political economies grew dramatically in importance. Throughout the post-war Keynesian era of capitalism, nationally embedded firms were more likely to compromise with organized labour and workers because of their interests in avoiding externalities such as layoffs affecting local consumer demand and long-term investment, or government intervention in industries facing economic difficulty (Crouch 2014). This is decreasingly common as global firms have the capability to operate in many jurisdictions, and do not need to consider the negative implications for consumer demand of low wages or flexible employment among their national, regional, or international workforces (ibid.). Consequently, in the context of global competition or economic downturn, government officials have had to accommodate firm demands for lower labour costs and greater employer discretion in workplaces by deregulating labour markets and fostering higher levels of non-standard employment

In addition, recent structural developments to business and their new operating priorities have also led, governments to be more accommodating to business (Dicken 2011; Dixon 2014). Leading global firms – in the advanced capitalist countries as well as the rapidly growing economies of China, Brazil, and India – have readily adopted new global financial models to run their operations and have developed global operations through mergers and acquisitions as well as greenfield investments in China and South East Asia (UNCTAD 2012). Pushed by institutional investors and the involvement of private equity firms, global multinationals have quickly adopted outsourcing, offshoring, subcontracting, and franchising arrangements as central modes of operation (Milberg and Winkler 2013). And to take advantage of global operations for lower costs, MNCs have integrated human resource departments, developed financial procedures to pressure affiliates to lower labour costs, or used outsourcing across their operations to shift production to the most efficient locales (Edwards, Marginson, and Ferner 2013). Such new economic realities have been critical in making governments compete for new investment and jobs by decentralizing collective bargaining, facilitating non-standard labour contracts, and introducing “activation” measures into social policy programs by tying income support to job requirements, irrespective of the terms and conditions of employment.

As table 3.2 suggests, firms’ global capacities and operations are now substantial and remained so after the Financial Crisis. Prior to the crisis in 2007, global multinationals and their affiliates accounted for 30 per cent of gross operating revenues (“turnover”) in host economies; more than 79 per cent in Ireland and approximately 20 per cent in the United States as well as Finland and Italy. After the crisis, global firms still accounted for more than 28 per cent of turnover. While full employment data are still unavailable, it appears that many MNCs were able to adjust operations by retrenching in core markets and expanding in non-OECD countries without affecting corporate revenues (Milberg and Winkler 2013).

Table 3.2. Share of Foreign-Controlled Affiliates in Manufacturing, 2007 and 2011 (% total turnover in corporate operating revenues)

Turnover 2007 |

Turnover 2011 |

|

|---|---|---|

Ireland |

79.0 |

76.0 |

Canada (2006) |

51.5 |

52.0 |

United Kingdom |

45.1 |

45.0 |

Netherlands (2005) |

41.3 |

40.0 |

Sweden |

39.6 |

39.9 |

Austria |

39.3 |

41.0 |

Spain |

30.4 |

26.9 |

France |

29.7 |

28.5 |

Norway |

27.8 |

25.0 |

Germany (2006) |

27.2 |

28.5 |

Denmark |

26.0 |

26.1 |

United States |

21.2 |

23.0 |

Italy |

18.7 |

17.8 |

Finland |

18.4 |

16.5 |

Median |

30.1 |

28.5 |

Sources: OECD (2010) and OECD AMNE Database.

In a number of leading manufacturing countries, such as the United States, Germany, and small exporting countries of high-tech and pharmaceuticals such as Switzerland, Sweden, and Finland, multinational operations and sales far outstrip domestic operations, giving firms options on how to best generate returns, despite declines in home country operations (OECD 2010). That firms were able to retain considerable cash and liquid asset holdings – as well as increase dividend payouts as strategies for profitability (Milberg and Winkler 2013) rather than invest in new capital and hiring – further supports the argument that global firms had far more options than previously nationally located firms, and that such flexibility gave them far more leverage in dealing with governments and reacting to the economic downturn.

Such developments suggest that the emergence of global firms has allowed them to shed labour and restructure in the wake of the crisis, while boosting profitability and shareholder returns. With the ability to shift production and investment to lower-cost producing regions on more flexible terms, firms were able to reform their workplaces either by laying off workers or by taking advantage of state-enforced changes to collective bargaining arrangements – often both. Where firms were limited in the capacities to adjust global operations, they took the opportunity the crisis afforded them to shed workers and use government support to bargain major wage and benefit concessions with their unionized workforces (Crouch 2014; Hermann 2014). These developments across rich world democracies strongly suggest that rather than diversity of firms and employment systems, the Financial Crisis has contributed to the increasing convergence of global firm operations around more hierarchical systems that privileged short-term financial objectives, labour shedding, and – where possible – non-union operations or workforces where union representatives and institutions could be more easily circumvented.

Moreover, unlike governments in the past, because of the global size and flexibility of firms, policy officials systematically privileged MNCs while allowing inequality, low-wage work, and poverty to expand. Instead of seeking to advance protection or – in the case of Western Europe – social citizenship, governments used their policy tools to foster more competitive labour markets and lower the labour and social costs for firms. As part of the ongoing shift towards “post-democracy,” these political outcomes strongly imply a more uncompromising neoliberal stance towards labour markets and collective bargaining – a stance that no longer accepts the need to balance the extension of business and markets by broader labour institutions and employment protection.

Trade Unions in Decline

New analysis has also begun to explore why unions have been decreasingly able to respond to or resist neoliberal politics and policy – before or after the crisis. Since the crisis, governments have placed new restrictions on union organizing and bargaining in North America, and firms have sought to advance the decentralization of collective bargaining institutions while seeking concessions throughout North America and Western Europe (Marginson, Keune, and Bohle 2014; Milkman 2013; Peters 2012). At the same time, governments have imposed liberalizing and deregulatory measures on their public sectors in order to reduce labour costs and public expenditures. In the United States, a number of state-level governments removed collective bargaining rights from public sector employees, restricted bargaining to wages, and banned strikes and binding arbitration (Milkman 2013; Rosenfeld 2014). In the EU, policymakers used “country-specific recommendations” and bilateral agreements to push for changes to national bargaining outcomes and procedures (Hermann 2014). In exchange for financial support, countries like Greece, Spain, Portugal, Latvia, Romania, and Ireland have had to reduce their minimum wages, downwardly adjust wages in the public sector, and decentralize collective bargaining (ETUI 2014). Added to this have been new reform efforts by the EU to restrict minimum wages and formally end wage indexation.

More widely, government officials continued their efforts to relax employment protection rules (Milberg and Winkler 2013). During the 1990s and 2000s, governments made extensive efforts to liberalize terms for fixed-term contracts, increase temporary foreign work permits, and reduce the level of protection afforded to temporary workers (Avdagic 2012). Since 2008, these endeavours have only increased (see table 3.3). As reported by the ILO, more than 50 per cent of advanced countries deregulated legislation for employees on permanent contracts; 26 per cent introduced further liberalizing reforms for fixed-term contracts (also known as temporary contracts) (ILO 2012). Most national policymakers increased the maximum length of fixed-term contracts, while widening the number of reasons for their conclusion and reducing the level of protection ascribed to them. Other governments reduced administrative procedures on collective dismissals, increasing the numerical benchmarks for a dismissal to trigger legislative intervention. Overall, these policy reforms have expanded the opportunities open to employers to increase their part-time and temporary workforces.

Table 3.3. Deregulation of Employment Protection, 2008–2012

Countries with change (%) |

Countries with negative change (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

Permanent contracts |

49 |

76 |

Temporary contracts |

26 |

44 |

Collective dismissals |

29 |

50 |

Source: ILO (2012).

The declining influence of organized labour on public officials provides one suggestive reason for these developments, and why government responses did little more than expose more workers to higher levels of unemployment and non-standard employment. Over the past few years, scholars have explored the impacts of globalization and labour market deregulation on democratic mobilization and how internationalization has led to a notable deterioration in the power resources of organized labour (Gumbrell-McCormick and Hyman 2013; Hacker and Pierson 2010; ILO 2011a; Streeck 2014). Trade unions and the growing number of workers in low-wage work and non-standard employment, it is claimed, face increasing challenges to their political effectiveness while making it even more difficult to jointly act as “coalitions of influence” within mainstream politics (Moody 2007; Tattersall 2010). Above all, organized labour has borne the brunt of flexibilization and non-standard employment, and unions have lost members and seen their contracts fragmented or weakened (Baccaro and Howell 2011; Sisson 2013). This has led to an erosion in the capacities of organized labour to mobilize more widely within communities and among low-wage workers, and has limited the ability of organized labour to influence public officials or limit the concessions demanded by firms (Baccaro and Avdagic 2014; Peters 2012; Pontusson 2013; Rosenfeld 2014). These problems have been only magnified since the Financial Crisis of 2007–8.

Traditionally, unions played major political roles in their democracies, educating members about politics and policy, reaching out to citizens through advocacy campaigns and community support, and acting as valuable allies for political parties of the left. But the current erosion in trade union power has come just at the time that rising inequality has disadvantaged a growing majority of citizens, who now feel that government is passing beyond popular involvement and control (Mair 2013; McBride and Whiteside 2011). More and more, it is claimed, the decline in the reach and clout of organizations representing workers and lower-income citizens is compounding the crisis in voter confidence in government and worsening the widespread political disengagement and withdrawal of citizens from the political process (Gumbrell-McCormick and Hyman 2013; Crouch 2006). The results have been increasing government indifference to the concerns of organized labour as well as significant attempts by public officials to deregulate labour relations and minimize the scope of collective bargaining and employment protection – even in Western Europe, where in the wake of the Financial Crisis a number of governments have imposed severe austerity measures (Albo and Evans 2011; Heyes, Lewis, and Clark 2012; Keune and Vandaele 2013; Nolan 2011).

Since the onset of the global recession in 2008, labour movements in both North America and Western Europe have faced a number of challenges. In the United States, state governments have cut public sector jobs and wages, and led by Wisconsin, public officials have liberalized public sector industrial relations by limiting union rights for public employees, banning strikes and arbitration, and restricting bargaining for wages (Moody and Post 2014). State governments in the Midwest have also introduced “right to work” legislation (clauses that require union-represented workers to pay dues or equivalent fees for union representation) in labour-management contracts, seriously restricting the long-term viability of workplace unionization.

In Western Europe, initially short-time work agreements were bargained with government support and maintained jobs through a combination of measures including reduced hours, freezes in basic pay, suspension of pay premiums, and alternatives to redundancy such as redeployment (Glassner and Keune 2010). But since 2010, business has demanded new concessions and the generalization of flexible employment and decentralized bargaining (Marginson, Keune, and Bohle 2014). Governments have accommodated by freezing wages and laying off public sector employees, as well as by undertaking measures to erode centralized or coordinated bargaining across Europe. In the countries most affected by the crisis – Spain, Portugal, Ireland, Greece – the EU/ECB/IMF have offered financial assistance only on the condition that governments dismantle their current labour market regulations and bargaining systems, and privatize their transport and energy sectors (Hermann 2014). But more widely, many countries including Germany and Sweden have introduced structural reforms in order to extend the downward flexibility of wages and improve cost competitiveness. The result has been a continuing decline of union density and members (table 3.4).

Table 3.4. Declining Union Densities and Collective Bargaining Coverage

Union density (change 1990–2008) |

Bargaining coverage (change 1990–2008) |

Union density (decline 2008–11) |

Bargaining coverage (decline 2008–11) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Austria |

-17.8 |

1.0 |

-1.3 |

– |

Belgium |

-2.0 |

– |

-2.5 |

– |

Canada |

-5.5 |

-7.5 |

– |

-3.0 |

Denmark |

-11 |

-3.7 |

-0.3 |

– |

Finland |

-1.9 |

10.3 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

France |

-11.4 |

-1.75 |

– |

– |

Germany |

-15.9 |

-11.1 |

-1.1 |

-3.0 |

Italy |

-16.2 |

-2.9 |

2.2 |

– |

Netherlands |

-15.1 |

0.4 |

-0.6 |

1.0 |

Norway |

-5.2 |

3.3 |

1.3 |

– |

Sweden |

-11.2 |

2.2 |

-1.8 |

– |

Spain |

2.1 |

-3.6 |

1.0 |

-7.0 |

UK |

-12.5 |

-20.4 |

-1.5 |

-2.4 |

US |

-4.0 |

-4.7 |

-0.3 |

-0.7 |

Average |

-9.1 |

-2.8 |

-0.2 |

-1.0 |

Sources: OECD Labour Market Statistics and ICTWSS Database.

Prior to the crisis from 1990 to 2008, union density declined on average by 16 per cent across Western Europe and by 4 per cent in the United States. After the crisis, density continued to decline, as did bargaining coverage. But most notable were the membership drops. In the United States, from 2008 through 2013, public sector union membership fell by 622,000, a result of public worker job cuts and labour law reforms (Moody and Post 2014). Union membership in the private sector fell even further between 2008 and 2012 with a decline of 1,228,000. In Western Europe, union membership also declined significantly. In the EU 15, the number of unionized workers fell by 1.1 million, with the steepest declines occurring in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Spain after the collapse of their housing and construction sectors, but equally significant declines in Germany, Greece, Denmark, and the Netherlands occurred as employers laid off workers, and governments sold off public utilities and infrastructures (ETUI 2014).

Part of the reason that organized labour was unable to halt the loss of unionized jobs and the fragmentation of bargaining systems was its inability to mobilize as widely and as militantly as in the past. In the 1970s and 1980s, the most effective weapon of organized labour against government and employer attempts to undermine wages and erode conditions of employment was to use economic and political strikes (Rosenfeld 2014). Strike waves reached their peaks during the recessions of the mid-1970s and early 1980s. However, these incidences of industrial conflict have continued to decline over the past generation, often by more than eighty in terms of workdays lost from strike activity for many countries. And with a few notable exceptions in the wake of the Financial Crisis – such as Greece, Spain, Ireland, and Portugal – strikes have declined even further in size and frequency (Streeck 2013). Without the wider mobilization of workers, unions have often been unable to build wider public support or pressure government officials to enact alternative policies.

Another problem faced by unions has been the internal difficulties created by trying to maintain employment while bargaining wage concessions and job flexibility. In facing more aggressive MNCs and firms demanding concessions, and governments seeking efficiencies, unions have been under enormous pressures to make concessions in order to retain jobs. But in dealing with these circumstances, unions have often adopted defensive strategies that have led to bargaining agreements that have “two-tiered” their memberships, disenchanted activists, and put national and international union locals in competition with one another over wages and benefits. In return for job security for those members not laid off or offered retirement packages, unions have given wage, pension, and employment concessions often while also accepting speed-up, job-loading, and more irregular hours. Such bargaining and workplace arrangements have not only limited internal solidarity within unions, they have also made it far harder for unions to expand external solidarity within their localities. Splits between “insiders” and “outsiders” are thus limiting the development of new forms of union representation, organization, and activity. And in the wake of the crisis, where bargaining has been increasingly concessionary, unions have found it difficult to actively support the upsurge of resistance and campaigning in the global Occupy Wall Street movement, or to be seen by the activists themselves as critical for a wider progressive coalition.

There is also evidence that international strategies of global unionism and coordinated bargaining and advocacy failed to limit the reach of MNCs and often led to further internal and international conflicts of interest, both before and after the crisis (Fairbrother, Levesque, and Hennebert 2013). In North America, unions have combined public advocacy and awareness campaigns at shareholder meetings with protests and job actions (Murnighan and Stanford 2013). In Western Europe, global union federations such as IndustriALL have sought to coordinate bargaining across Europe to prevent auto and steel makers from using concessionary agreements in one country to attain wage and jobs reductions in another. But one such problem unions have faced is that greater effort at international campaigning and bargaining have not made up for lack of local mobilizing, education, and external solidarity (Peters 2010). In Western Europe, there has been a shift in the internal power balance between trade unions and works councils, with the latter increasing their influence over bargaining outcomes at the expense of the former – the works councils’ first priority is employment security, and they have been more willing to make concessions than industrial unions would. This has led to internal battles and the fragmentation of workforces as employers exploit union fears with job loss, demanding opt-out clauses from higher-level collective agreements, striking deals with unions to pay new entrants less than stipulated by collective agreements, and increasing outsourcing in plants. The consequences of such defensive postures, internal conflict, and limited returns for global unionism has been to make unions increasingly hollow organizations with declining capacities to engage in collective practices (Baccaro and Avdagic 2014).

Overall, the aggregate evidence points to a growing number of problems for the organizational fortunes of labour across North America and Western Europe. Inequality is increasing, union bargaining strength and coverage are slowly eroding, and workers are increasingly finding themselves in non-standard, part-time, and temporary jobs. There is still variety with differences in the political and institutional strength of firms and organized labour. Labour movements in the Nordic countries, for example, have coped best with the challenges of globalization and neoliberalism, even going some way to maintaining an employment model that continues to uphold wages and limits inequality while maintaining strong employment insurance and training programs (Thelen 2014). But even in these countries, there are growing numbers of temporary workers, and unions have been forced to take major bargaining concessions, while governments have introduced a wide range of privatization and outsourcing reforms in the public sector that have undermined jobs and union solidarity.

In other countries though, like the United States, unions have been so weakened that they are unable to accomplish much (Rosenfeld 2014), while in Canada, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom, unions protect only a minority of workers but are unable to counter wider trends of low-wage work, de-unionization, and declining wages and benefits (Baccaro and Howell 2011; Peters 2012). In the wake of the crisis, union density has continued to fall, most notably in the largest economies as well as in the countries deepest in economic difficulty. This has been matched with a falloff of industrial conflict, and a tendency for bargaining to be either further restricted or become more differentiated and accommodating to company demands for wage and employment concessions. Meanwhile, public officials’ restrictive microeconomic policies have focused on wage restraint, alongside renewed emphasis on market forces, both of which have further eroded labour’s position in national political economies. The results have been that inequality continues to grow, job quality declines, and citizens’ ability to make meaningful demands on firms or policymakers erodes.

Conclusion

Taking a wider comparative view, this chapter seeks to make transparent two structural roots of major policy shifts in the wake of the Financial Crisis and to show how they furthered neoliberal, supply-side reforms in the majority of rich world democracies. The argument here suggests that the economic shock provided by the crisis gave powerful organized interests yet another lever to make further incremental shifts to policy that advantages business and finance at the cost of organized labour and citizens more generally. The size and scope of powerful MNCs within national economies appears critical in public officials’ decision-making, leading to policy responses that backed firm efforts to shed unionized workers and restructure with lower-cost non-standard labour. So too the decline in organizing and mobilizing capacities of organized labour shaped government responses. With limited abilities to conduct strikes and coordinate bargaining and international actions, unions were unable to influence policymakers or sway the public more generally of the need for greater distributive measures and more employment-oriented policies.

Consequently, a crisis caused by the deregulation of financial markets has contributed to wider firm demands for more neoliberal deregulation of labour markets and ongoing downward pressure on union density and protective labour market institutions. The results have been a continuing decline in measures that provided people with some security in income and employment, and a substantive rise in non-standard employment and income inequality – trends that continued the transformations of state and society into a more neoliberal and inegalitarian direction. Understanding the economic forces and the structural changes to the relationships between government, business, and finance is critical to explaining these outcomes and the ongoing reforms to states and public policies in North America and Western Europe.

References

Albo, Greg, and Bryan Evans. 2011. “From Rescue Strategies to Exit Strategies: The Struggle over Public Sector Austerity.” In Socialist Register 2011: The Crisis This Time, ed. L. Panitch, G. Albo, and V. Chibber, 283–308. Pontypools, Wales: Merlin.

Atkinson, Anthony B., and Thomas Piketty, eds. 2007. Top Incomes over the Twentieth Century: A Contrast between Continental European and English-Speaking Countries. New York: Oxford University Press.

– eds. 2010. Top Incomes: A Global Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press.

Atkinson, Tyler, David Luttrell, and Harvey Rosenblum. 2013. How Bad Was It? The Costs and Consequences of the 2007–2009 Financial Crisis. Dallas: Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Avdagic, Sabina. 2012. “Partisanship, Political Constraints, and Employment Protection Reforms in an Era of Austerity.” European Political Science Review 5 (3): 431–55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1755773912000197.

Baccaro, Lucio, and Sabina Avdagic. 2014. “The Future of Employment Relations in Advanced Capitalism: Inexorable Decline?” In The Oxford Handbook of Employment Relations: Comparative Employment Systems, ed. A. Wilkinson, G. Wood, and R. Deeg.New York: Oxford University Press. Online.

Baccaro, Lucio, and Chris Howell. 2011. “A Common Neoliberal Trajectory: The Transformation of Industrial Relations in Advanced Capitalism.” Politics & Society 39 (4): 521–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0032329211420082.

Brufman, Leandro, Lisana Martinez, and Rodrigo Pérez Artica. 2013. What Are the Causes of the Growing Trend of Excess Savings of the Corporate Sector in Developed Countries?New York: World Bank.

Crouch, Colin. 2006. Post-Democracy. Malden, MA: Polity.

– 2011. The Strange Non-Death of Neo-Liberalism. Malden, MA: Polity.

– 2014. “The Neo-Liberal Turn and the Implications for Labour.” In The Oxford Handbook of Employment Relations: Comparative Employment Systems, ed. Adrian Wilkinson, Geoffrey Wood, and Richard Deeg. New York: Oxford University Press. Online.

Dicken, Peter. 2011. Global Shift: Mapping the Changes Contours of the World Economy. New York: Sage Publications.

Dixon, Adam D. 2014. The New Geography of Capitalism: Firms, Finance, and Society. New York: Oxford University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199668236.001.0001.

Duménil, Gérard, and Dominique Lévy. 2011. The Crisis of Neoliberalism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Economist Intelligence Unit. 2014. What’s Next: Future Global Trends Affecting Your Organization: Evolution of Work and the Worker.New York: Economist.

Edwards, Tony J., Paul Marginson, and Anthony Ferner. 2013. “Multinational Companies in Cross-National Context: Integration, Differentiation, and the Interactions between MNCs and Nation States.” Industrial & Labor Relations Review 66 (3): 547–87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/001979391306600301.

Emmenger, Patrick, Silja Hausermann, Bruno Palier, and Martin Seeleib-Kaiser. 2011. “How We Grow Unequal.” In The Age of Dualization: The Changing Face of Inequality in De-industrializing Societes, ed. P. Emmenger, S. Hausermann, B. Palier, and M. Seeleib-Kaiser, 3–26. New York: Oxford University Press.

European Trade Union Institute (ETUI). 2014. Benchmarking Working Europe 2014. Brussels: ETUI.

European Commission. 2012. Tackling the Financial Crisis: Banks. Brussels: European Commission.

Fairbrother, Peter, Christian Levesque, and Marc-Antonin Hennebert, eds. 2013. Transnational Trade Unionism. Routledge Studies in Employment and Work Relations. New York: Routledge.

Gautie, Jerome, and John Schmitt, eds. 2010. Low-Wage Work in the Wealthy World. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Glassner, Vera, and Maarten Keune. 2010. Negotitating the Crisis? Collective Bargaining in Europe after the Economic Downturn. Geneva: ILO.

Goos, Maarten, Alan Manning, and Anna Salomons. 2009. “Job Polarization in Europe.” American Economic Review 99 (2): 58–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.2.58.

Grossman, Emiliano, and Cornelia Woll. 2013. “Saving the Banks: The Political Economy of Bailouts.” Comparative Political Studies 47 (4): 574–600.

Gumbrell-McCormick, Rebecca, and Richard Hyman. 2013. Trade Unions in Western Europe: Hard Times, Hard Choices. New York: Oxford University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199644414.001.0001.

Hacker, Jacob, and Paul Pierson. 2010. Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer – And Turned Its Back on the Middle Class. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Hermann, Christoph. 2014. "Structural Adjustment and Neoliberal Convergence in Labour Markets and Welfare: The Impact of the Crisis and Austerity Measures on European Economic and Social Models." Competition & Change 18 (2): 111–30.

Heyes, Jason, Paul Lewis, and Ian Clark. 2012. “Varieties of Capitalism, Neoliberalism and the Economic Crisis of 2008–?” Industrial Relations Journal 43 (3): 222–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2338.2012.00669.x.

Horn, Laura. 2012. Regulating Corporate Governance in the EU. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/9780230356405.

Huwart, Jean-Yves, and Loïc Verdier. 2013. Economic Globalisation: Origins and Consequences. Paris: OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264111905-en.

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2011a. Global Employment Trends 2011: The Challenge of a Jobs Recovery. Geneva: ILO.

– 2011b. Global Wage Report 2010/2011. Geneva: ILO.

– 2011c. A Review of Global Fiscal Stimulus. EC-IILS Joint Discussion Paper Series no. 5. Geneva: ILO/International Institute for Labour Studies.

– 2012. World of Work Report 2012. Geneva: ILO.

– 2013. Global Wage Report 2012/13. Geneva: ILO.

Kalleberg, Arne L. 2011. Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s to 2000s. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Keune, Maarten, and Kurt Vandaele. 2013. “Wage Regulation in the Private Sector: Moving Further Away from a Solidaristic Wage Policy.” In The Transformation of Employment Relations in Europe, ed. J. Arrowsmith and V. Pulignano, 88–110.New York: Routledge.

King, Desmond, and David Rueda. 2008. “Cheap Labor: The New Politics of ‘Bread and Roses’ in Industrial Democracies.” Perspectives on Politics 6 (2): 279–97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1537592708080614.

Mair, Peter. 2013. Ruling the Void: The Hollowing of Western Democracy. New York: Verso.

Marginson, Paul, Maarten Keune, and Dorothee Bohle. 2014. “Negotiating the Effects of Uncertainty? The Governance Capacity of Collective Bargaining under Pressure.” Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research 20 (1): 37–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1024258913514356.

McBride, Stephen, and Heather Whiteside. 2011. Private Affluence, Public Austerity: Economic Crisis and Democratic Malaise in Canada. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing.

Milberg, William, and Deborah Winkler. 2013. Outsourcing Economics: Global Value Chains in Capitalist Development. New York: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139208772.

Milkman, Ruth. 2013. “Back to the Future? US Labour in the New Gilded Age.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 51 (4): 645–65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bjir.12047.

Moody, Kim. 2007. US Labor in Trouble and Transition: The Failure of Reform from Above, the Promise of Revival from Below. New York: Verso.

Moody, Kim, and Charles Post. 2014. “The Politics of US Labour: Paralysis and Possibilities.” Socialist Register 2015: Transforming Classes 51:295–317.

Moran, Michael. 2009. Business, Politics, and Society. New York: Oxford University Press.

Murnighan, Bill, and Jim Stanford. 2013. “‘We Will Fight This Crisis’: Auto Workers Resist an Industrial Meltdown.” In From Crisis to Austerity: Neoliberalism, Labour and the Canadian State, ed. T. Fowler.Ottawa: Red Quill Books. Online.

Nolan, Peter. 2011. “Money, Markets, Meltdown: The 21st Century Crisis of Labour.” Industrial Relations Journal 42 (1): 2–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2338.2010.00594.x.

OECD. n.d. Activity of Multi-National Database (AMNE). Paris: OECD. http://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/amne.htm.

– n.d. OECD Income Distribution Database (IDD). Paris: OECD. http://www.oecd.org/social/income-distribution-database.htm.

– 2008. Growing Unequal: Income Distribution and Poverty in OECD Countries. Paris: OECD.

– 2009. OECD Economic Outlook Interim Report March 2009. Paris: OECD.

– 2010. Measuring Globalisation: OECD Economic Globalisation Indicators. Paris: OECD.

– 2011a. Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising. Paris: OECD.

– 2011b. OECD Employment Outlook 2011. Paris: OECD.

– 2012. Employment Outlook 2012. Paris: OECD.

– 2014. Tackling High Inequalities, Creating Opportunities for All. Paris: OECD.

Peters, John. 2010. “Down in the Vale: Corporate Globalization, Unions on the Defensive, and the USW Local 6500 Strike in Sudbury, 2009–2010.” Labour (Halifax)66:73–106.

– 2012. “Free Markets and the Decline of Unions and Good Jobs.” In Boom, Bust and Crisis: Labour, Corporate Power and Politics in Canada, ed. J. Peters, 16–54. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing.

Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Piketty, Thomas, and Emmanuel Saez. 2014. “Inequality in the Long Run.” Science 344 (6186): 838–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1251936.

Pontusson, Jonas. 2005. Inequality and Prosperity: Social Europe vs Liberal America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

– 2013. “Unionization, Inequality, and Redistribution.” British Journal of Industrial Relations51:797–825.

Pontusson, Jonas, and Damian Raess. 2012. “How (and Why) Is This Time Different? The Politics of Economic Crisis in Western Europe and the United States.” Annual Review of Political Science 15:13–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-031710-100955.

Rosenfeld, Jake. 2014. What Unions No Longer Do. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674726215.

Rueda, David. 2008. “Political Agency and Institutions: Explaining the Influence of Left Governments and Corporatism on Inequality.” In Democracy, Inequality, and Representation: A Comparative Perspective, ed. P. Beramendi and C.J. Anderson, 169–200.New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Sachs, Jeffrey D. 2012. The Price of Civilization: Economics and Ethics after the Fall. Toronto: Vintage Canada.

Saez, Emmanuel, and Michael R. Veall. 2005. “The Evolution of High Incomes in North America: Lessons from the Canadian Evidence.” American Economic Review 95 (3): 831–49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/0002828054201404.

Salverda, Weimar, and Christina Haas. 2014. “Earnings, Employment, and Income Inequality.” In Changing Inequalities in Rich Countries, ed. W. Salverda, B. Nolan, D. Checchi, I. Marx, A. McKnight, I. Toth, and H. van de Werhorst. New York: Oxford University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199687435.003.0003.

Sisson, Keith. 2013. “Private Sector Employment Relations in Western Europe: Collective Bargaining under Pressure.” In The Transformation of Employment Relations in Europe, ed. J. Arrowsmith and V. Pulignano, 13–32.New York: Routledge.

Stiglitz, Joseph E. 2010. Freefall: America, Free Markets, and the Sinking of the World Economy. New York: W.W. Norton.

Streeck, Wolfgang. 2013. “The Crisis in Context: Democratic Capitalism and Its Contradictions.” In Politics in the Age of Austerity, ed. A. Schafer and W. Streeck, 262–86.Malden, MA: Polity.

– 2014. Buying Time: The Delayed Crisis of Democratic Capitalism. New York: Verso.

Streeck, Wolfgang, and Jelle Visser, eds. 2006. Governing Interests: Business Associations Facing Internationalization. New York: Routledge.

Tattersall, Amanda. 2010. Power in Coalition: Strategies for Strong Unions and Social Change. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Thelen, Kathleen. 2014. Varieties of Liberalisation and the New Politics of Social Solidarity. New York: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107282001.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2012. World Investment Report 2012. New York: United Nations.

Wilks, Stephen. 2013. The Political Power of the Business Corporation. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.4337/9781849807326.