Irma Eréndira Sandoval-Ballesteros

MANY PEOPLE HOPED THAT the emergence of vigorous political competition over the last two decades in Mexico would have a transformative impact on the struggle against corruption and for transparency. But this has not been the case. Competition between political parties has not translated into better oversight or real accountability. An improved equilibrium between social interests and government institutions is still missing.

In this chapter, I explore the Mexican case to learn how to understand, define, and practice transparency in a way that prevents the “freezing” of democratization processes in the developing world. I argue that corruption and opacity can be satisfactorily addressed only in a broad, coordinated manner that takes into account both political-economic considerations and fundamental power disparities. Until this type of strategy is implemented, corruption will remain one of the key features of Mexican politics and society.

Only ten years ago, Mexico’s emerging democracy was the poster child of transparency reform. In February of 2007, an important reform in the area of access to information gave constitutional backing to Mexico’s 2002 freedom of information law and received unanimous support from all political parties. Its aim was to improve compliance with the law, bringing state and municipal governments up to federal standards. Since then, at least on paper, Mexico stands out as one of the best designed access to information regimes in the world. For instance, no fewer than three chapters in the present volume identify the Mexican regime as a global leader.1

Nevertheless, compliance has been highly problematic. It has been particularly difficult to open up the judiciary and the legislature to public scrutiny, and there is little evidence that access to information has actually transformed the authoritarian ways of exercising power in Mexico. Difficulties with implementation and compliance arose very early, calling into question the long-term impact of what is—on paper—an impressive law.

In the first part of this chapter, I summarize my proposed structural approach to corruption and a democratic-expansive approach to transparency. In the second part, I discuss the gap between Mexico’s advanced legal transparency regime and the persistence of vast corruption. In the final section, I explore the linkages between privatization and corruption and the consequent need to extend oversight and transparency beyond the public sector.

A DEMOCRATIC-EXPANSIVE UNDERSTANDING OF TRANSPARENCY

Mexico’s recent history suggests that the struggle to give transparency meaning ultimately depends just as much on political will and social mobilization as it does on legal reforms or technical formulas. I begin by outlining what I call a democratic-expansive vision of transparency—one that imagines transparency not as a brake on bureaucracy but as a means to genuinely expand democratic governance—and explaining why it must guide a new understanding of accountability in Mexico.

The typical approach to transparency reform proposes a basic dose of bureaucratic hygiene to improve internal control and perhaps also to establish a so-called culture of legality among citizens and public employees. This approach envisions opacity as largely a technical or administrative problem. It focuses on bureaucratic fixes rather than on the generation of tools and conditions through which citizens can defend their fundamental rights.

Armed with this bureaucratic perspective, large teams of experts and advisors in law, political science, and public administration travel throughout the world issuing reports and recommendations on how to improve access to information. Academics, commissioners, and other officials continually organize high-level forums, conferences, and costly meetings to analyze proposals and government responses. Some of them offer suggestions to improve the treatment of government information: facilitating electronic records requests, modernizing Internet procurement procedures, or decreasing the time it takes to respond to citizen inquiries, for example.

This work is not without value, but unfortunately it is not powerful enough to overcome the enormous resistance to transparency and accountability in Mexico and similar countries.2 The problem these countries face is not merely technical but political and structural at its root. In principle, it is not in the immediate interest of top public servants, judges, and elected officials to reveal detailed information about many of their actions, decisions, budgets, and expenditures. Transparency can lead to scandal, and this type of public attention can inflict significant damage on political careers.

The tendency in Mexico has therefore been to defend transparency rhetorically, without following up with concrete steps to realize its transformative potential. Thus emerges what we might call a “public relations” approach, the other side of the coin of bureaucratic or technical myopia. The public relations approach is a discursive facade that uses the rhetoric of transparency to procure legitimacy and stability for governments3 and trust for investors4 in the face of growing demands for accountability on the part of citizens.

A satisfactory response to those demands requires a democratic-expansive understanding of transparency. This approach views transparency as a matter of political rights and citizenship rather than bureaucratic hygiene.5 The principal goal of transparency, in this view, is to assist in a collective project of invigorating democracy and accountability. Civil society organizations play a critical role in this project: monitoring government compliance with access to information laws, ensuring that the transparency agenda is not co-opted by politicians or bureaucrats, and connecting transparency efforts to the concerns of the common citizen.6

Just as transparency needs to be understood in broader and more political terms, so too must corruption. For decades, the concept of corruption often has been reduced to a mere synonym for low-level public officials receiving bribes. Mexico’s anticorruption efforts have focused on such bribes and related behaviors. They have largely disregarded “structural corruption,” a specific form of social domination that is characterized by the misappropriation of resources and enabled by a pronounced inequality of power. Structural corruption encompasses both illegal acts and perfectly lawful but morally questionable acts. In general, it focuses less on the discrete pecuniary maneuvers of individual officials and more on the accumulation of power and privilege by illegitimate means. It sees corruption not only as a cause but also as a symptom of democratic failure.

If corruption is not just a question of low-level public servants filling their pockets at the expense of common citizens, then combating it will not principally be an issue of disciplining or reeducating rogue actors.7 The real corruption problems lie, on one hand, in the capture of the state by powerful economic interests and, on the other hand, in the pyramidal structure of institutionalized rent-seeking in which bureaucrats are forced to extort citizens by orders of their superiors. Structural corruption also is reflected in what might be called, following Alvaro Delgado,8 a “pact of impunity” between Mexico’s two main political parties—the Revolutionary Institutional Party (PRI) and the right-wing National Action Party (PAN)—that has marked the transition to democracy in recent years. This informal agreement enabled the PAN to rule vast zones of the country while the PRI remained the dominant party throughout the transition period when PAN occupied the presidency. The most important effect of this arrangement is that it effectively insulated political and economic elites from society and allowed practices such as closed-door deals, money laundering, collusion between businesses and politicians, illicit finance in electoral processes, and opaque privatization to flourish. Real regime change never occurred.

In moving beyond the bribery model of corruption, a structural perspective on corruption also moves beyond the public sector. It worries about abuses of power and zones of opacity wherever they occur, including when private entities capture government regulators or when they take over functions normally reserved for government.9 Following the same logic, the democratic-expansive approach to transparency that I advocate would extend disclosure and accountability controls normally reserved for the public sector into the private sphere.

THE DISCONNECT BETWEEN TRANSPARENCY AND CORRUPTION

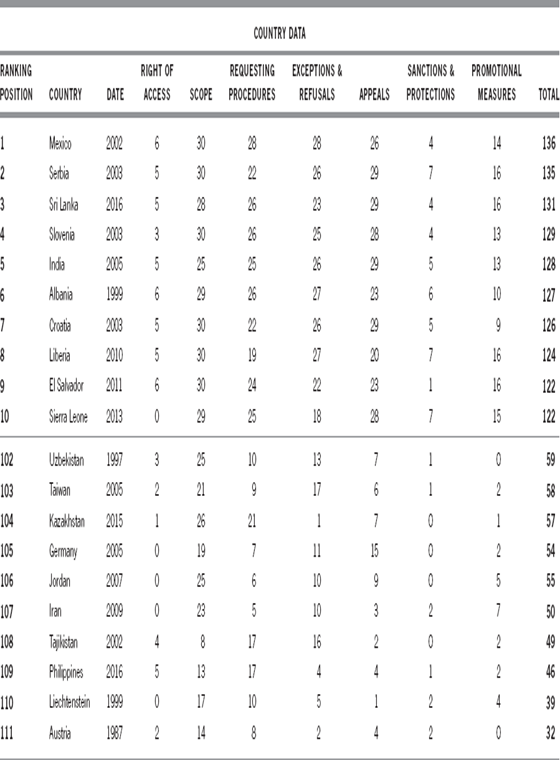

There is a stark contrast between Mexico’s highly developed transparency regime and its high levels of corruption. Whereas Mexico is consistently evaluated as having one of the most sophisticated legal frameworks for transparency in the world (table 14.1), its rankings on the international scoreboards for corruption are consistently poor.

TABLE 14.1 Global Right to Information Rating

Mexico’s transparency law has particularly strong procedural guarantees.10 For instance, it provides for total access when the requested information is necessary for investigating grave violations of human rights or crimes against humanity. This, in theory, establishes a blanket public interest override for all information related to critical issues such as political assassinations, the persecution of ethnic or political minorities, or government censorship of the press. In practice, there have been serious problems with the interpretation and implementation of this clause. Nevertheless, its mere existence was a major achievement for the pro-access community and distinguished Mexico in the global context, although other nations have incorporated similar provisions in their access laws over the past decade.11

Another innovation is that the law requires every government office to set up a liaison office (oficina de enlace) to handle access to information requests and to respond to such requests within twenty working days. If the office fails to respond in time, the answer is automatically considered to be positive and the information must be handed over in the following ten working days. The existence of such an “afirmativa ficta” clause is crucial because it puts considerable pressure on government agencies to respond expeditiously to citizen requests.

This contrasts with the U.S. Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). A recent report by a congressional committee confirmed that “mute refusals” are common responses to access to information requests in the United States. This seriously undermines the effectiveness of one of the most developed freedom of information legal frameworks in the world.12

Furthermore, the agency in charge of enforcing transparency, Mexico’s National Institute for Transparency, Access to Information and Personal Data Protection (INAI), stands out as a particularly powerful oversight organization. The INAI functions simultaneously as an administrative court in charge of reviewing the government’s negative responses to information requests and as an ombudsperson responsible for strengthening the “culture of transparency” in both government and society.

The U.S. framework now includes a modest ombudsperson’s office, but this Office of Government Information Services does not have the powers of an administrative court, and U.S. policy makers could learn from the Mexican example. For instance, the congressional report cited above suggests that, in general, U.S. government agencies do little to proactively sponsor a culture of transparency or to promote a friendly environment for users of FOIA. The United States also has no equivalent to the mandate included in Article 6 of the Mexican Constitution that dictates “maximum disclosure of public information” as the overriding principle in the interpretation and implementation of freedom of information guarantees.

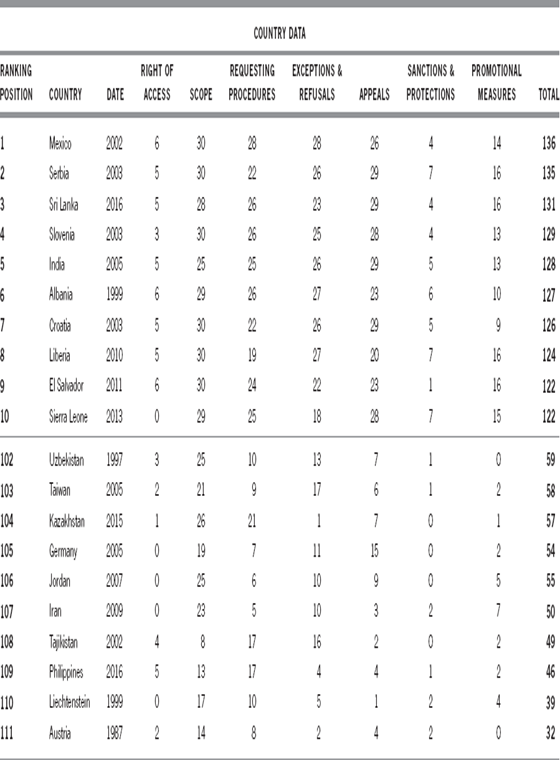

Notwithstanding its admirable institutional design of transparency, Mexico remains one of the most corrupt countries in the world. In 2016, it received a failing score of 34 out of 100 on the Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index, tied with Moldova, Sierra Leone, and Honduras (table 14.2).13 Mexico is ranked at the same level as Laos, Azerbaijan, and Paraguay and at a lower level than Bolivia, Panama, Sri Lanka, Niger, Zambia, Rwanda, and Trinidad and Tobago. Mexico is the most corrupt country in the OECD14 and even more corrupt than most of the emerging powers, equally or more corrupt than monarchies and dictatorships, and just as corrupt as countries that in recent years have experienced wars, genocides, humanitarian crises, and famines.

TABLE 14.2 Corruption Perception Index, 2016

| RANK |

COUNTRY |

SCORE |

| 1 |

Denmark |

90 |

| 1 |

New Zealand |

90 |

| 3 |

Finland |

89 |

| 4 |

Sweden |

88 |

| 5 |

Switzerland |

86 |

| 6 |

Norway |

85 |

| 7 |

Singapore |

84 |

| 8 |

Netherlands |

83 |

| 9 |

Canada |

82 |

| 10 |

Germany |

81 |

| 10 |

Luxembourg |

81 |

| 10 |

United Kingdom |

81 |

| 13 |

Australia |

79 |

| 14 |

Iceland |

78 |

| 15 |

Belgium |

77 |

| 15 |

Hong Kong |

77 |

| 17 |

Austria |

75 |

| 18 |

United States |

74 |

| 19 |

Ireland |

73 |

| 20 |

Japan |

72 |

| 101 |

Gabon |

35 |

| 101 |

Niger |

35 |

| 101 |

Peru |

35 |

| 101 |

Philippines |

35 |

| 101 |

Thailand |

35 |

| 101 |

Timor-Leste |

35 |

| 101 |

Trinidad and Tobago |

35 |

| 108 |

Algeria |

34 |

| 108 |

Côte d’Ivoire |

34 |

| 108 |

Egypt |

34 |

| 108 |

Ethiopia |

34 |

| 108 |

Guyana |

34 |

| 113 |

Armenia |

33 |

| 113 |

Bolivia |

33 |

| 113 |

Vietnam |

33 |

| 116 |

Mali |

32 |

| 116 |

Pakistan |

32 |

| 116 |

Tanzania |

32 |

| 116 |

Togo |

32 |

| 120 |

Dominican Republic |

31 |

| 120 |

Ecuador |

31 |

| 120 |

Malawi |

31 |

| 123 |

Azerbaijan |

30 |

| 123 |

Djibouti |

30 |

| 123 |

Honduras |

30 |

| 123 |

Laos |

30 |

| 123 |

Mexico |

30 |

| 123 |

Moldova |

30 |

| 123 |

Paraguay |

30 |

| 123 |

Sierra Leone |

30 |

| 131 |

Iran |

29 |

| 131 |

Kazakhstan |

29 |

| 131 |

Nepal |

29 |

| 131 |

Russia |

29 |

| 131 |

Ukraine |

29 |

| 136 |

Guatemala |

28 |

| 136 |

Kyrgyzstan |

28 |

| 136 |

Lebanon |

28 |

| 136 |

Papua New Guinea |

28 |

| 142 |

Guinea |

27 |

| 142 |

Mauritania |

27 |

| 142 |

Mozambique |

27 |

| 145 |

Bangladesh |

26 |

| 145 |

Cameroon |

26 |

| 145 |

Gambia |

26 |

| 145 |

Kenya |

26 |

| 145 |

Madagascar |

26 |

| 145 |

Nicaragua |

26 |

| 151 |

Tajikistan |

25 |

| 151 |

Uganda |

25 |

| 153 |

Comoros |

24 |

| 154 |

Turkmenistan |

22 |

| 154 |

Zimbabwe |

22 |

| 156 |

Cambodia |

21 |

| 156 |

Democratic Republic of Congo |

21 |

| 156 |

Uzbekistan |

21 |

| 159 |

Burundi |

20 |

| 159 |

Central African Republic |

20 |

| 159 |

Chad |

20 |

| 159 |

Haiti |

20 |

| 159 |

Republic of Congo |

20 |

| 164 |

Angola |

18 |

| 164 |

Eritrea |

18 |

| 166 |

Iraq |

17 |

| 166 |

Venezuela |

17 |

| 168 |

Guinea-Bissau |

16 |

| 169 |

Afghanistan |

15 |

| 170 |

Libya |

14 |

| 170 |

Sudan |

14 |

| 170 |

Yemen |

14 |

| 173 |

Syria |

13 |

| 174 |

Korea (North) |

12 |

| 175 |

South Sudan |

11 |

| 176 |

Somalia |

10 |

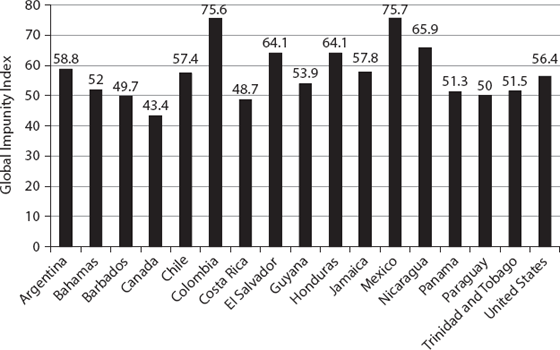

The Siamese twin of corruption is impunity, and this may be the key to explaining the disconnect between transparency and corruption in the country. According to the Center for Studies on Impunity and Justice at the University of the Americas Puebla, Mexico ranks first on the 2017 “Global Impunity Index” out of all Latin American nations (figure 14.1).15

FIGURE 14.1 Global Impunity Index

Source: Center for Studies on Impunity and Justice at the University of the Americas, Puebla.

Mexico’s transparency control bodies are hesitant to follow up and enforce their decisions, and often they do not apply any sanctions to public servants who have intentionally hidden or altered public information.16 During the time that the Mexican FOIA has been in force, there have been only a few cases in which a public official has been sanctioned in any way for obstructing the law’s implementation.17 To be sure, sanctions against government officials for lackluster efforts to respond fully and promptly to requests for access to information are rare to nonexistent elsewhere in the world too. But in Mexico, the absence of sanctions both reflects and contributes to a much larger pattern of impunity.

Under Mexico’s new General Act of Transparency and Access to Public Information, the INAI has broad authority to initiate a “penalty procedure” and sanction officials who hide or alter public information. The law provides a long list of particular circumstances—at least fifteen instances—under which sanctions might apply, and it further provides that economic penalties may not be paid with public funds. As in other areas of Mexican life where impunity for wrongdoing is the norm, the problem is not the law itself but rather its enforcement.

In addition, instead of pushing for reforms that would expand and guarantee the effectiveness of transparency, President Enrique Peña Nieto has decided to roll back protections for accountability. For instance, the most recent reforms to the Mexican FOIA grant impunity to the executive in two ways. First, the legal advisor of the president has been given the authority to bring challenges to the Supreme Court of Justice against final resolutions taken by the INAI, at least when national security is at stake. Second, the law now includes a prohibition against bringing the president of the republic to justice for cases of corruption—effectively codifying the informal practice of presidential impunity. This is highly problematic, particularly after the case known as “Peña’s White House,” in which the president and his wife acquired a mansion built for them by Juan Armando Hinojosa Cantú, CEO of HIGA Group, a beneficiary of major contracts for public infrastructure.18 More recently, a new corruption scandal has raised allegations that Brazilian construction giant Odebrecht paid about ten million dollars in bribes in exchange for contracts and that the money ended up financing President Peña Nieto’s 2012 electoral run.19

Thus, although the Mexican FOIA has been cast as the cornerstone of the effort to achieve open and accountable public administration, it has not generated an honest government committed to the public interest. Public oversight may under certain conditions be able to keep those in power scrupulous in managing public resources. But the “first world” transparency regime achieved at the normative and institutional levels in Mexico has not, for the most part, empowered citizens to oversee the internal operation of government institutions.

For decades, the Mexican government has functioned as a sophisticated mechanism for consolidating economic and political privilege and defending the elite from the social and economic demands of popular groups inspired by the revolutionary agenda reflected in the Mexican Constitution. For more than seventy years, Mexico’s authoritarian state-party regime ruled the country through the PRI. This regime came to an end in 2000, and a new political party, PAN, that supposedly was different both in ideology and social base took over and governed for twelve years. But the alternation in office of PRI and PAN did not transform the basic way power and authority are managed in Mexico. Opacity, corporatism, patronage, and capture—features that PAN systematically denounced when in opposition—were adopted by the party when it won power.

Indeed, in some respects, the situation has become even worse. For instance, as a result of the fragmentation of the monolithic state-party edifice, the governors of the thirty-one states and the mayor of Mexico City have increased their relative power over their respective territories. This entrenchment of federalism has not necessarily led to greater accountability or better service provision. Provincial governors in Mexico are infamous for their heavy-handed attempts to control politics, economics, and society. Previously they were at least held accountable by the president, but today they have more freedom to abuse their power. The weakened standing of the presidency has made some of these governors into the modern-day equivalent of feudal lords.20

Moreover, under the administration of President Peña Nieto, the freedoms of expression and protest have come under heavy fire. Marches are systematically repressed, social and political leaders are jailed or assassinated, and journalists are censored, forced out of their jobs, or murdered without an effective government response. On May 15, 2017, Mexican journalist Jesús Valdez, director and founder of the weekly newspaper Ríodoce and correspondent for the newspaper La Jornada, was murdered. He was one of the most renowned journalists in the country and spent much of his career reporting on organized crime, drug trafficking, and the collusion between crime and government (narco-gobiernos) and its impact on society.21 His death brings the total number of journalists murdered in Mexico between 2000 and 2017 to 127.22 More than thirty journalists have been assassinated during the Peña Nieto administration. In the first five months of 2017 alone, a handful of journalists were murdered and many more were attacked all over the country. In 2016, 99.75 percent of attacks against journalists went unpunished.

Mexico, in short, is the home of impunity. Freedom of expression and the right to access information are supposedly the oxygen of democracy. Both elements are fundamental rights, and both are being severely undermined by organized violence and other repressive forces that operate with effective insulation from, or even the acquiescence of, the state.

The traditional exclusion of society is even more prominent in the economic realm. In fact, transparency and accountability of financial and economic policies are two of the major challenges in contemporary Mexico. Financial authorities have systematically closed the door to access to information about these policies.

In other work, I have tried to demonstrate the opacity still predominant in the economic arena. For example, the large-scale corruption present in the 1994 bailout of Mexico’s banking sector took place against a growing chorus of celebratory rhetoric about transparency in the country. Using the language of “banking secrets,” the financial authorities held back investigations of extensive irregularities and kept the details of the bailout hidden.23 Mexico’s transparency laws have come a long way since 1994, but they continue to fall short with regard to economic, financial, and monetary issues—with likely negative effects not only on freedom of information but also on economic development.

Mexico is one of the most unequal countries on the planet. It is home to one of the richest men in the world, Carlos Slim, as well as to more than 65 million poor people.24 Although Mexico is the fourteenth largest economy in the world and a member of the OECD, its scandalous 48.1 Gini Coefficient25 reveals serious problems with the distribution of income.

In addition, government spending is still highly ineffective, and the civil service remains in its infancy.26 Abuses of human rights are widespread,27 and poverty and inequality have not significantly declined in recent years. In other words, neither transparency law nor regime change in Mexico seems to have led to a major modification in the way government does business. Even though some authors have described the transition to democracy as closely connected with broader liberalizing reforms, this has not been the case in Mexico. A large literature assumes a basic synergy between markets and democracies. Much of this literature pays little attention to the underlying power relations, which may tend to centralize processes of private sector decision making rather than stimulate socially beneficial competition.

In sum, extreme economic inequality and the political capture of the state by powerful economic elites have undermined many of the goals associated with the transition to democracy in Mexico—and have reduced the effective meaning of transparency.

BREAKING THE ANTI–PUBLIC SECTOR BIAS

Around the world, “public” responsibilities and governance functions of the highest importance, such as education, health, public safety, pensions, prisons, financial services, and a wide variety of urban infrastructure and development programs, have been absorbed by private corporations, associations, nongovernmental organizations, independent contractors, or quasi-government entities. This transformation presents enormous challenges for transparency. It opens up a wide range of emergency exits for actors who are unwilling to submit to the new forms of accountability that have been applied to government institutions in recent years. Very few national laws on access to information provide for strong, effective mechanisms of transparency applicable to private companies that carry out public functions. This situation is the Achilles’ heel for the contemporary legal practice of transparency.28

According to Mexican law, in particular Article 142 of the Mexican FOIA, individual and corporate entities that receive public resources or perform acts of public authority should be subject to transparency requirements. This is a good start, but it is clearly insufficient. The rule in the private sector is not transparency but opacity. Mexican corporate law is packed with provisions for bank secrecy, tax secrecy, trade secrets, and other secrecy privileges that are said to protect competition and the privacy of investors. This secrecy carves out a niche of impunity and opacity for the benefit of economic powers and interest groups outside the formal channels of the state.

Effective oversight by society and public opinion depends on the Mexican FOIA having the capacity to render transparent not only traditional formal powers but also the new “powers that be” such as business organizations, transnational corporations, financial giants, and the media. This is what is really at stake in breaking the anti–public sector bias that takes the state to be the source of all opacity and corruption that a FOI law must confront. Implicitly, markets and private spheres are treated as clean arenas free of corruption and waste.

In reality, in Mexico as in the rest of Latin America, corruption is intimately linked to privatization and neoliberalism.29 The dominant perspective depicts the wave of economic reforms that took place during the 1990s in Latin America as the imposition of a cold economic orthodoxy on a wasteful bureaucracy and a corrupt political class.30 Yet, as my research on the changes in the Mexican banking sector reveals, these supposedly “liberalizing” economic reforms have led to more instead of less corruption and waste.31 In general, neoliberalism should not be conceptualized as an economic project with political implications but as a political project with economic consequences. The reforms did not reduce the state and empower technocracy; rather, the reforms reshaped the state and political power in accord with the interests of new distribution coalitions. Throughout this process, opacity has prevailed.

Today Mexico’s political regime seems not to have learned its lesson regarding the mutually reinforcing character of opacity, unconstitutionality, and impunity. With the enactment by President Felipe Calderón of the Law of Public-Private Associations in 2011, the country has opened the door to private ownership and control of a wide range of public services, including highways, hospitals, jails, and schools. This legal transformation, of doubtful constitutionality according to leading Mexican legal scholars,32 has meant private takeover of existing government services and has created incentives for private corporations to propose new construction projects to the government to serve profit-making rather than the public interest.

Both the administration of past president Calderón and that of President Peña Nieto have justified the Law of Public-Private Associations as necessary in order to compensate for the fiscal crisis that limited public investment in crucial social sectors. This transfer of public services to private hands has dramatically reduced the reach of basic transparency and anticorruption oversight because private projects are not required to subject themselves to the same accountability controls as normal government projects. This trend is already reviving the failed experience of privatization of the 1990s.33

PRI and PAN governments have been united in empowering corporations over people. They have demonstrated a lack of respect for the Mexican Constitution and its social legacy. Under President Peña Nieto, Mexico has privatized its oil and electricity industries,34 rolled back protections for labor, aggressively imposed neoliberal education reforms,35 increased covert surveillance of its citizens,36 and consolidated the militarization of law enforcement. This “privatization solution” or “public-privatization answer” to the fiscal crisis of the state rewards the very actors responsible for the original problem. Tax revenues are so low in Mexico precisely because powerful economic elites dodge taxes by hiding their money in offshore accounts or simply intimidating treasury authorities.37

One recent example of how the opacity of the private sector can lead to impunity for government corruption is the global scandal in which the Mexican government stands out again for its participation in the Brazilian construction company Odebrecht’s efforts at money laundering and bribery. Odebrecht, whose founder is now in jail, paid enormous sums in bribes for contracts to the highest levels of twelve Latin American governments.38 In Mexico, it is accused of having bribed government institutions with over US$11 million during the administrations of presidents Calderón and Peña Nieto.

In 2016, the Panama Papers revealed that a Panamanian law firm helped set up thousands of secret shell companies for notorious Mexican oligarchs and drug lords in a variety of tax havens. The CEO of the state oil company PEMEX, Emilio Lozoya, was revealed to be one of the firm’s principal clients. In 2017, the Odebrecht settlement—which was made publicly known thanks to investigations by the U.S. Department of Justice—shed light on a private company spending millions of dollars bribing politicians and political parties across Latin America. Once this hemispheric network of corruption was made known by the international press, the agency in charge of combating corruption in Mexico, the Public Function Ministry, had to acknowledge the existence of contracts between corporations (such as Odebrecht) known to have bribed politicians across Latin America and Mexican state entities such as the Federal Commission of Electricity and PEMEX. The details of these contracts, however, continue to be withheld from the public.39

Again and again, a combination of personal impunity and selective disclosure, especially when it involves powerful economic interests, demonstrates both the depths of structural corruption and the inadequacy of transparency strategies that target government entities exclusively.

CONCLUSION

Mexico’s democratic transition has failed to empower society or settle accounts with the past. Instead, as in many Latin American transitions, democratization in Mexico often has meant no more than the diversification of the power bases for the same moguls and oligarchs as before. This is the underlying reason the Mexican FOIA has not lived up to its promise or its global hype.

I have made two key arguments in this chapter. First, we need a new framework for understanding transparency and combating corruption that takes into account the failings of old accountability strategies. Second, we should go beyond both the anti–public sector bias and the bureaucratic obsessions that undergird most studies of corruption and transparency in the developing and the developed world alike.

Democratic theorists have long agreed that citizens need reliable information about how the system works in order to exercise their rights as full participants in a democracy. Mexico is not fulfilling this basic condition. In countries like Mexico, reformers should adopt a structural understanding of corruption and tie the protection of transparency to a vision of strengthening citizen participation in democracy. The former defines corruption as the abuse of power plus impunity in the absence of citizen participation. The latter insists on the extension of transparency and accountability controls normally reserved for the public sector into the private sphere. Anything less fails to take into account broader realities of social and political power and thereby fails to establish concrete links between transparency, accountability, democracy, and justice.

NOTES

Assistance provided by Isabel Salat and Ma. Fernanda Soto was instrumental in organizing the data used in this chapter.

1. Katie Townsend and Adam A. Marshall, chapter 11; Kyu Ho Youm and Toby Mendel, chapter 12; and Gregory Michener, chapter 13.

2. A set of proposed amendments to Bosnia and Herzegovina’s law on freedom of access to information, which aim to withhold large volumes of information about the functioning of public bodies, is a recent example of such resistance. For more on this case, see “OSCE Media Freedom Representative Expresses Concern About Access to information Law Amendments in Bosnia and Herzegovina,” June 4, 2013, www.osce.org/fom/102269.

3. See Secretaría de la Función Pública, Transparencia, Buen Gobierno y Combate a la Corrupción en la Función Pública (Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2005).

4. See Brad Rawlins, “Measuring the Relationship Between Organizational Transparency and Employee Trust,” Public Relations Journal 2 (Spring 2008): 1–21.

5. See Irma Eréndira Sandoval, “Transparency Under Dispute: Public Relations, Bureaucracy, and Democracy in Mexico,” in Research Handbook on Transparency, ed. Padideh Ala’i and Robert G. Vaughn (Northampton, Mass.: Edward Elgar, 2014), 157–84.

6. See Irma E. Sandoval-Ballesteros, “Hacia un proyecto democrático-expansivo de transparencia,” Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales, Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City, 2013.

7. Another implication of the structural perspective is that it is time to put behind us both “modernizationist” approaches that frame corruption as principally an issue of economic underdevelopment and moralistic approaches that focus on the cultural roots of the problem. Recent work has demonstrated that economic growth and a wide variety of cultures can coexist with corrupt practices. For more on these themes, see Ernesto Garzón Valdés, “Derecho, Ética y Política,” Center of Constitutional Rights, 1993; Irma E. Sandoval, “From Institutional to Structural Corruption: Rethinking Accountability in a World of Public-Private Partnerships,” Edmond J. Safra Research Lab Working Papers, No. 2, 2013. See also Susan Rose-Ackerman and Bonnie J. Palifka, Corruption and Government: Causes, Consequences, and Reform (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016); and Susan Rose-Ackerman, “The Law and Economics of Bribery and Extortion,” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 6 (2010): 217–38.

8. See Alvaro Delgado, El Amasiato, el pacto secreto Peña-Calderón (Mexico City: Ediciones Proceso, 2016).

9. See Irma E. Sandoval-Ballesteros, “Enfoque de la corrupción estructural: poder, impunidad y voz ciudadana,” Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México-Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales, Revista Mexicana de Sociología 78, no. 1 (enero-marzo, 2016): 119–52. México, D.F. ISSN: 0188-2503/16/07801-05.

10. See Katie Townsend and Adam A. Marshall, chapter 11, this volume.

11. See John M. Ackerman and Irma E. Sandoval, “The Global Explosion of Freedom of Information Laws,” Administrative Law Review 58 (2006): 85–130.

15. See UDLAP, “Index of Global Impunity—Mexico,” August 2017, www.udlap.mx/cesij/files/IGI-2017_eng.pdf. For an interesting analysis that also finds impunity to be one of the key elements explaining the lack of progress in fighting corruption despite Mexico’s model of access to information law, see Eduardo Bohórquez, Irasema Guzman, and Germán Petersen, “Control de corrupción en México; ¿la impunidad neutraliza el efecto de los avances en la transparencia?” Este País 297: (January 2016).

16. The INAI itself has been experiencing severe internal turmoil. Several years ago, there was an open dispute among commissioners regarding violations of the guarantee of anonymity of citizen requests. In 2013, INAI’s Internal Audit Unit began an investigation of a commissioner who was accused by an INAI colleague of a conflict of interest. The commissioner allegedly had made requests for information from her own computer, under a pseudonym, and then presented and defended those same requests.

At the same time, Mexico’s investments in transparency have proved highly costly for society. In some states, there is more public money for information commissioners’ salaries than for public education in indigenous communities. On average, commissioners receive more than forty-three times the minimum wage, versus the multiple of three that an average teacher receives in Mexico. See Cristina Gómez, “ITAIT destaca por sueldos según estudio del CIDE,” accessed March 3, 2018, http://m.milenio.com/region/CIDE-ITAIT-estudio_sueldos_Tamaulipas_0_467953246.html.

17. See Anexo 3.1, “Denuncias de hechos por persistir el incumplimiento de las resoluciones emitidas por el pleno del INAI en 14vo. Informe de Labores al H. Congreso de la Unión,” 2016, http://inicio.inai.org.mx/SitePages/Informes-2016.aspx. See also John Ackerman, El Instituto Federal de Acceso a la Información Pública: Diseño, Desempeño y Sociedad Civil, Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores de Antropología Social-Instituto de Investigaciones Histórico-Sociales, Universidad Veracruzana, 2007.

18. See Juan Montes, “Mexico Finance Minister Bought House from Government Contractor,” Wall Street Journal, December 11, 2014. See also Redacción AN, “La casa blanca de Enrique Peña Nieto,” Aristegui Noticias, 2014, http://aristeguinoticias.com/0911/mexico/la-casa-blanca-de-enrique-pena-nieto; Joshua Partlow, “Mexico’s President Apologized for a Corruption Scandal. But the Nightmare Goes on for the Reporter Who Uncovered It,” Washington Post, July 22, 2016.

19. See Parker Asmann, “Was Mexico President’s 2012 Campaign Funded by Odercrecht?,” InSight Crime, October 27, 2017.

20. For general background on the topic, see Wayne Cornelius, Todd A. Eisenstadt, and Jane Hindley, eds., Subnational Politics and Democratization in Mexico (La Jolla, Calif.: Center for U.S.-Mexico Studies, UC San Diego, 1999); Austin Bay, “Mexico Versus Mexico: The Battle over Impunity,” Times Record News, May 3, 2017. As an example, consider the case of the ex-governor of the state of Tabasco, Andres Granier, who has been accused of plunging the state into debt by squandering and embezzling millions of dollars before fleeing to Miami. State prosecutors have found 88.5 million pesos, about $7 million in cash, in an office used by his former treasurer, Jose Saiz. Granier himself was secretly recorded bragging about owning hundreds of suits and pairs of shoes and about shopping exclusively at Beverly Hills luxury stores. See Richard Fausset and Cecilia Sanchez, “Former Mexican Official’s Boasts Add Fire to Corruption Probes,” Los Angeles Times, June 12, 2013.

21. Editorial Board, “In Mexico, Journalism Is Literally Being Killed Off,” Washington Post, May 21, 2017.

23. For a comparative analysis of Zedillo’s and Obama’s bailouts, see Irma E. Sandoval, “Financial Crisis and Bailout: Legal Challenges and International Lessons from Mexico, Korea and the United States,” in Comparative Administrative Law, ed. Susan Rose-Ackerman and Peter L. Lindseth (London: Edward Elgar, 2010), 543–68.

28. Irma E. Sandoval, “Enfoque de la corrupción estructural: poder, impunidad y voz ciudadana,” Revista Mexicana de Sociología 78 (2016): 119–52.

29. Luigi Manzetti, “Political Opportunism and Privatization Failures,” in Contemporary Debates on Corruption and Transparency: Rethinking State, Market and Society, ed. Irma Eréndira Sandoval (Washington, D.C.: World Bank and National Autonomous University of Mexico, 2011), 95–116.

30. Ezra Suleiman and John Waterbury, eds., The Political Economy of Public Sector Reform and Privatization (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1990); Marc E. Williams, Market Reforms in Mexico: Coalitions, Institutions and the Politics of Policy Changes (Lanham, Md.: Rowan & Littlefield, 2001). See also Anne O. Krueger, “Government Failures in Development,” NBER Working Paper No. 3340, www.nber.org/papers/w3340.

31. Irma E. Sandoval-Ballesteros, Crisis, Rentismo e Intervencionismo Neoliberal en la Banca: México (1982–1999) (Mexico City: Centro de Estudios Espinosa Yglesias, 2011). See also Sandoval, “Financial Crisis and Bailout.”

32. Asa C. Laurell and Joel Herrera, “Claves para entender los contratos de asociación público-privada,” in Interés Público, Asociaciones Público-Privadas y Poderes Fácticos, ed. Irma E. Sandoval (Mexico City: National Autonomous University of Mexico, 2015), 123–44.

33. Héctor E. Schamis, “Avoiding Collusion, Averting Collision: What Do We Know About the Political Economy of Privatization?,” in Contemporary Debates on Corruption and Transparency: Rethinking State, Market and Society, 35–76.

35. See Azam Ahmed and Kirk Semple, “Clashes Draw Support for Teachers’ Protest in Mexico,” New York Times, June 26, 2016.

37. Christopher Woody, “Leaked Documents Show the Mexican President’s Close Friend Moved $100 Million Offshore After Corruption Probe,” Business Insider, April 4, 2016.

38. David Segal, “Petrobras Oil Scandal Leaves Brazilians Lamenting a Lost Dream,” New York Times, August 7, 2015.

39. For instance, during President Calderon’s term, PEMEX signed a contract with an Odebrecht’s subsidiary, Braskem, to administer sixty-six thousand daily ethanol barrels under “preferential prices.” This costly material would be destined for a polyethylene factory, which was envisioned to be built in the south of Mexico in Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz. This contract has been declared under reserve for twenty-five years. Odebrecht also received lucrative contracts from the public electricity company. See Raúl Olmos, “Pemex publica contratos con Odebrecht pero censura los datos centrales,” Animal Político, April 6, 2016.