10

A Brief Tour

Once we’d dived, it was time to settle into the environment that would become home for the next three months. This seems like the best time for me to explain the main compartments within the submarine and give you a very brief description of what went on in each. Basically, the boat was split into three separate parts: front section – living, fighting, sleeping, washing, working, engineering, eating and entertaining; middle section – Armageddon (the missiles); back section – reactor, life-support services and propulsion. Let’s start with everything forward of the missile compartment. This was the fighting hub of the submarine – its controls, the tactical heart of the boat, home of the attack team, and also where we ate, slept, shat, washed and entertained.

The nerve and command centre of the boat was ship control, situated in the Control Room and operated by a two-man band. It was from here that the submarine was manoeuvred and changed depth, as well as made changes to its course, all of which were dictated by the duty OOW, XO or captain. The foreplanesman was responsible for depth changes by manoeuvring the foreplanes up or down, and for changes in course to port and starboard by operation of the rudder. The afterplanesman was responsible for keeping the boat level at differing depths, most notably periscope depth, and for maintaining the degree of pitch within the correct parameters so the boat remained stable, particularly when diving or returning to periscope depth. It was essential he kept the correct angle on the boat, and the two men needed to work in perfect harmony to ensure the boat was at the right depth and angle, and on course. Failure to do this, especially at periscope depth, made them an easy target for the wrath of the skipper or XO if the periscope dipped in and out of the water, or conversely, we were too deep, so the captain couldn’t see anything at all.

Ship control in many ways resembled an aircraft cockpit, with the foreplanesman sitting in the right-hand seat and the afterplanesman in the left-hand seat. Both used joysticks reminiscent of a commercial airliner as they soared through the ocean depths.

When the boat dived in normal patrol conditions, a form of autopilot was available that engaged both a fixed depth and a pre-set angle, so that the operation could be performed by a single person. Behind the autopilot, on the port-facing forward side, was the systems console, which was operated by the chief or petty officer stoker, with another stoker doing checks. It was usually manned by two sailors when on patrol, three if we were doing a run to periscope depth. I’ve touched on the systems console already; black in appearance, with switches everywhere, it looked like the sort of panel you’d find in an East European electric power plant in the 1960s. Buttons and switches had to be selected at the right time, in the right sequence, otherwise you could have a mini shit-storm on your hands, most notably when blowing the slop, drain and sewage tank to expel everyone’s waste. As well as all the diving and surfacing shenanigans, it was from here that the periscopes – both attack and search – were raised and lowered.

When on patrol the submarine used SINS (ship’s inertial navigation system), which through motion and rotation, computerised sensors and dead reckoning was able to continuously calculate the position of the submarine regardless of any movement. SINS was a mixture of accelerometers and gyroscopes mounted on a stable platform, which provided latitude and longitude, heading, speed and depth, and this would all feed into the navigation room and the missiles to give an accurate picture of where we were. If Resolution circumnavigated the world without ever once returning to periscope depth, SINS would need to be accurate to around 200 to 300 yards, to permit a sufficiently precise missile launch. A back-up to this was a regular return to periscope depth, where we would raise the BRN mast* and take a location pinpoint from global positioning satellites that locked down our position to within a few feet, after which it would be time to run off deep and hide sharpish. The computers that fed the missile systems would be constantly updated, as it was essential that the missiles knew the exact navigational position of the submarine prior to launch, so they could home in precisely on the target and not end up redecorating a vast expanse of the Soviet tundra.

The nav centre was a highly restricted space that was out of bounds to unauthorised personnel as it contained information on our patrol location. Where the submarine went on patrol was a secret closely guarded from most of the crew; only around a dozen men had access to the nav centre, and apart from the captain, XO and navigator, none of them knew our exact location. To preserve the secrecy of the boat’s position, the charts in this room were always displayed upside down to deter anyone from taking a peek.

The middle of the control room was where you’d find that iconic piece of submarine kit everyone is familiar with, the attack and search periscopes. Periscopes in submarines date back to 1888 – the French experimental submarine Gymnote had one fitted – but it wasn’t until the First World War that periscopes started to have a serious impact militarily, as submarines from both sides quickly gained a reputation for stealth and cunning. They have been a mainstay of operations ever since, and are used for navigation, safety and warfare (ranging and targeting). The attack periscope on Resolution was seldom used, mostly on exercise in work-up or if we were taking part in war games – I remember helping with an attack that ‘sank’ an aircraft carrier off the west coast of Scotland on one particular frantic afternoon’s exercise.

Our very eccentric but legendary XO of the time said: ‘Stand by to surface and machine gun survivors.’ I think at least half of the crew thought he meant it. The attack periscope was longer and thinner than the search periscope, so the submarine could attack any potential targets from greater depth, and it was a lot smaller at the top, so was much harder to spot by any ships or planes that might have been out looking for us. It was monocular and fitted with various navigational aids, including a split-image rangefinder and horizon sextant, and had a de-icer for the top window, if required in colder climes.

The search periscope was binocular and bigger than the attack periscope, thus increasing the boat’s vulnerability when used at periscope depth as it was more conspicuous. If we weren’t at precisely the right depth near the surface, it could stick out above the water like a bulldog’s balls. It was, however, the normal choice for the captain whenever we returned to periscope depth; since it had a larger diameter than the attack periscope but retained the same level of magnification, it made for good, sound visuals, making it much more comfortable to use.

To the right of the periscopes, on the starboard side of the control room, was the CEP (contact evaluation plot), where I spent the majority of my time on the submarine when on watch. Here contacts were plotted in real-time in relation to the position of the submarine. Behind and to the right of this was the computerised fire-control system (which I also worked on), whose sole purpose was using different algorithms to work out the course, speed and range of any new contact picked up by the sound room to aid the captain in getting an overall tactical picture.

Next to the fire-control system heading aft was the underwater telephone. It tended to be left on for all of the patrol, which meant I could hear all the multifarious sounds of the deep. Behind that was the ARL (Admiralty Research Laboratory) table that was used on the surface for plotting the bearings for fixes taken from the periscope; it doubled as the LOP† when we dived, which was another time-bearing plot. Though seldom used, with the advent of the fire-control system it was another way of helping the captain work out a potential target’s course, speed and range, and was particularly useful when dealing with fast-moving vessels.

Finally, mounted against the wall in the control room, behind the LOP, was the bathythermograph. This was used to measure a combination of the water temperature and the velocity of sound in water while the boat traversed different depths of the oceans. A change of temperature in the sea from the surface to the different depths of a submarine’s operating spectrum causes thermoclines, the transient layers between warmer and colder water temperature that make it possible for a submarine to hide away, as they can impair sonar performance for the hunter. Sonar works effectively if the sub has a highly reflective steel surface and is in water of the same temperature as that from which the initial sonar waves are transmitted; in this case the sound waves will bounce off the target and go straight back to the ship.

Some oceans vary in temperature and, consequently, so does the speed at which sound travels through their water. Conditions where there is little temperature change from surface to operating depth are known as ‘isothermal’, which is bad news for a submarine being hunted as the sonar is clear. Ideally, what a submarine needs is a layer of the ocean with a rapid increase or decrease in water temperature over a few feet. Diving below this layer can significantly reduce the chances of being detected … so the deeper the better.

We took readings by inserting a card into the bathythermograph every time we went to periscope depth, checking whether any new thermoclines had developed. Also, as the nuclear deterrent, we had access to historical data collected by submarines over the years to use in our search for depth perfection and the best methods of avoidance.

Moving out of the control room towards the front of the boat on the same deck, we come to the electronic counter-measure office, which was manned at periscope depth by the tactical systems team, in which I served. This was used in conjunction with the electronic warfare mast, which would be raised by the captain to check whether there were any ships or planes in the area operating radar; we’d be able to pick up the strength of any signal or determine how close the contact might be.

Moving further forward, there was a locked room where the navigator kept his various charts to help us with plotting our way to and from the patrol area on the surface. Through the passage directly underneath the main access hatch, the wireless room and sound room stood opposite to one another. The sound room was quite simply the eyes – and indeed ears – of the submarine. When a sub is submerged, its main gatherer of information in relation to sound outside the pressure hull is sonar. Sounds are picked up using hydrophones mounted near or around the bow that are then translated into visual data by computers in the sound room and interpreted by the sonar chief/petty officer of the watch and his team. This in turn would be passed on to the control room, where the tactical systems team would do its best to track the target and work out its own range, course and speed.

Passive sonar worked best under a speed of 5 to 6 knots, and we usually operated below that speed at no more than walking pace to gain the maximum benefit. Active sonar emits a ‘ping’ (like you hear in Das Boot or the old John Mills war films) when sonar waves bounce off any target, making its range much easier to calculate, but in turn it can quickly give the boat’s position away due to the beam of energy – the ping – getting picked up by another submarine or boat. Listening passively means you’re relying on any contacts making enough noise, either generated by the sound of machinery or the propeller, to then filter through to your sonar, which can be operated at any depth.

Operators also looked out for what is known as the ‘Doppler effect’, which in simple terms is the increase in frequency of sound as something comes towards the boat, and the decrease as it moves away. This is part of the ‘Doppler shift’, when a contact being tracked either at periscope depth or in the deep suddenly alters course; the skipper would then have a shit fit because he’d have to use his self-taught computational skills (albeit honed to perfection) to work out new fire-control solutions on the target, with the aid of his attack team.

The wireless room, slightly aft of the sound room, was strictly out of bounds to non-authorised personnel. Manned by the radio operators, it was here that all the signals and general patrol information came in from Northwood, including ‘familygrams’ we received from our next of kin every seven to ten days or so. The captain would also receive general information from here about ship or submarine movements, whether hostile or friendly, that could encroach on our patrol area. All the signals that were transmitted from Command Centre at Northwood would be sent at low frequency and be picked up by the comms wire we trailed out the back of the submarine just below the surface of the water, then relayed to the eager beavers in the wireless room. While essential in terms of maintaining contact with Northwood, the comms wire rendered the submarine considerably longer, which made manoeuvring the boat particularly challenging.

Even without the comms wire deployed, when operating in the fishing waters of the Atlantic off the Irish coast, the potential risk of getting tagged in nets was pretty substantial. There have been a few occasions when subs have dragged along fishing vessels, having become entangled, even pulling them into the deep with tragic loss of life.

On one occasion a fishing vessel was visible through the periscope for a couple of days, constantly following us; every change of course we made, she followed suit, until it suddenly dawned on us, and indeed the fishing vessel, that we were dragging it around like a killer whale with its prey. We had it by the nets, and thank goodness their captain cut them away, otherwise we’d have provoked a national scandal: Nuclear Deterrent Drags Hard-Working Fishermen to Davy Jones’s Locker. The MOD would of course have denied all knowledge, I’m sure; they hardly ever comment on submarine operations, and when they do they’re fairly economical with the truth, working on a need-to-know basis with the premise that there’s seldom any need. Joe Public rarely needs to know much.

The sonar console space was the furthest forward on 1 Deck. As well as the mass of electronics needed to make the sonar work, it also housed air-cooled sonar. It proved to be a good place to hang out if I wanted some private time or to revise, both on my first patrol when I was studying for my dolphins badge and when I took educational qualifications later on in my service.

Let’s now head down to 2 Deck. From the missile compartment, work forward on the port side and you’ll find the captain’s cabin, the wardroom and the officers’ sleeping quarters. The captain was the only crew member with his own cabin, and from here he was able to listen in on all communications in order to keep abreast of developments when he wasn’t in the control room. There was a safe in his cabin where his instructions concerning where to go while on patrol were kept. Adjacent to the Captains cabin were the officers’ sleeping quarters, washrooms and toilets, all in close proximity, which was a fairly sobering experience, smell-wise. Officers ate every night in the wardroom, their meals having been prepared in the galley. I always found it amusing that grown men had to be waited on hand and foot in order to eat, but it was just part of the ‘toff and oik’ culture that was so prevalent in the British military at the time. I guess I simply never understood it. I was as much a stickler for Navy tradition as the next man, and I’m sure they were good at their jobs, but did they really need silver service deep under the North Atlantic?

On the starboard side working forward, you had the sick bay, the ship’s office and the coxswain’s office. The sick bay was obviously the doctor’s domain. I was never sure if someone became seriously ill what the precise position would have been; whether you’d have tried to get the casualty off the boat or just insisted on the doc carrying out an emergency operation. Appendicitis was the main worry, and I do know subsequent to my time on board that an XO I served with, who went on to command the Trident submarine HMS Vengeance, surfaced on patrol and had a sailor with appendicitis taken off the boat by helicopter. Wise choice. Of course, there was the other choice too – just don’t get ill.

The coxswain’s office was where the chief of the boat hung out. When I was doing my Part 3 training to qualify I’d go there once a week, full of dread and often despair, for him to test me on some hydraulic system, or in what sequence the ventilation fans would be restarted after an emergency, or about the rush escape procedure, or how torpedoes were fired. He always liked to end the meeting with a damage-control-type scenario, to which I’d be expected to know the answer.

‘Right, Humph. Two a.m. collision with a submarine at 200 feet, water starts pissing into the control room … you’ve got ten seconds, what you gonna do? Ten, nine, eight …’

I’d sit there, clueless, thinking I’d either be dead or sucked out into the sea, all the while going redder and redder trying to think of a smart-alec reply or something more intelligent. It was soul-destroying.

Then he’d just say, ‘You’ve fucked it, Humph, lost the whole crew. And it’s all your fault.’

Death by humiliation. Not that he ever held a grudge; it would all be forgotten 20 minutes later as he started on some other unfortunate trainee hunting for his dolphins.‡

The ship’s office was used by the petty officer chef, who’d be working out how many more tins of steak and kidney pud he had left and exactly when the eggs were going to run out; or the supply officer would be in there worrying when the loo roll would start having to be rationed. The leading writer would also use the office, to keep the boat’s administration ship-shape and up to date.

You then moved forward to the senior rates’ mess. Fitted out with a bar, it also doubled up as an operating theatre if required. Opposite was the upper senior rates’ bunk space and their annex, where the coxswain held court. At the bottom of the ladder from 1 Deck on the port side was the garbage ejector space, which quite literally used to fire out the rubbish – known as ‘gash’ – to the depths. Nowadays, to comply with international law, some of the gash is kept on board until the submarine returns to port. In my day it was broken down in a grinder and ejected via a vertical tube, the gash gun, having first been weighed down so it would sink all the way to the ocean floor. Also down here was the precipitator room, where high-voltage precipitators using electricity to attract dust particles removed them from the atmosphere.

Next, the galley directly in front was where a team of three chefs under the guidance of the petty officer chef would work wonders creating culinary delights for the crew in a small kitchen approximately 15 square feet in size. The meals were rich, plentiful and varied – an amazing feat when concocted in such conditions.

The wonderful chefs undertaking food prep in the very confined space of the galley. (Wood/Express/Getty Images)

Opposite the galley was the junior rates’ mess, where I tucked in to all my meals. The mess also doubled up as the main entertainment area in the boat, with quizzes, horse-racing nights, soap operas and cinema nights, when the latest Hollywood films were shown on two-spool cinema reels. It felt a bit like going to a small old-fashioned village hall with a pull-down screen, except we were deep under the North Atlantic. We also had keep-fit classes in there, and a religious service on a Sunday for anyone who felt the need.

Back to the port side now, and just forward of the galley was the scullery – with the garbage grinder – and the ship’s canteen, from which you could buy sweets and ‘goffa’ (fizzy drinks), booze and ‘snadgens’ (cigarettes). I’d run up a tab over the course of the patrol – easily a couple of hundred quid if the drink got the better of me – and I paid it off when I got back to shore. Between the scullery, galley and the pressure hull was the provisions store, which kept all the non-perishable food stuffs required for patrol.

Just before entering the torpedo compartment (the fore ends), the most forward part of the boat, there was a small hatch going down to 3 Deck that housed the freezer compartment and sufficient refrigerator space for the perishable foods, all mercilessly crammed in so we’d never grow hungry. It would also be used on rare occasions to temporarily house a dead body, should anyone be unfortunate enough to pop their clogs while at sea. I’m not too sure what the chefs would have made of it, though, clambering over a dead body to get to the frozen fish of the day. Fortunately, in my career we never had a patrol death.

Let’s now pass into the torpedo compartment through a bulkhead door. The boat was sub-divided into areas with bulkheads, giving the submarine an added safety feature; if there was a flood it could be contained by shutting the bulkheads and isolating the compartment where it occurred, then blowing the ballast tanks and returning to the surface tout suite. An issue certainly could have arisen, however, if the flooding was rapid and heavy; then people situated in the non-escape compartments of the submarine would have had a good chance of drowning. Hopefully, the boat would be in shallow enough water that an escape could be attempted via the escape hatches by the crew left in either of its ends. If not, the boat would implode at crush depth, so being in the escape hatches would be pointless anyhow, as the boat would be traversing at great speed and a rush escape futile and impossible.

The torpedo compartment was itself split into two decks. The bottom one was the business end where torpedoes were fired from their tubes. These tubes were basically an extension of the pressure hull, and to prevent flooding they had an inner (breech) and outer door (muzzle), which were opened and closed at different times. A torpedo was launched by equalising the pressure inside the tube with that of the seawater outside. The muzzle door opened and a water ram system thrust the torpedo out of the tube and away it went, wire-guided to the target.

If we had any extra guests on board, or there were more Part 3 trainees than usual, they’d have to sleep on camp beds down here, where they’d enjoy absolutely no privacy whatsoever. You’d have to get some kip under the rowdy junior rates’ space, nodding off to the loungy soundtrack of some 70s porn. In the rec space above, alongside the porn, movies were watched, and cards and ‘uckers’ – a board game very similar to Ludo – were played. It also doubled as the ship’s library, and was where all interviews for promotions or gaining your dolphins badge took place. Its other main military function was as the home of the forward escape compartment, which entered around the main escape hatch. For support there were oxygen generators, CO2 absorption units and oxygen-burning candles. The upper level was also full of air pipes and connections for breathing units, both static and portable, enabling the crew to breathe in the event of an escape.

Down to 3 Deck now, where from forward to aft it was another senior rates’ bunk space, as well as the laundry. This ran a couple of times a week for shirts, T-shirts and trousers, usually on a Monday, then overalls from the engineers on a Tuesday, to get the stench out. Within a couple of hours of putting on clean shirts, the tell-tale BO and sweat would return. Moving aft, the junior rates’ bunk spaces were spread over most of the remainder of the deck. You slept in close proximity to other members of your team so you were all together and easier to locate when woken up to go on watch. The bunks were small, with barely enough room to lie either on your side or flat on your back without your nose being squashed against the Formica of the bunk above. It was pitch-black down there, so sleeping was easy, although the dreams and the nightmares came easily too. The junior rates’ toilets, showers and washroom were also along here, as was the main battery under 3 Deck, in the event that we had to switch to diesel power instead of nuclear.

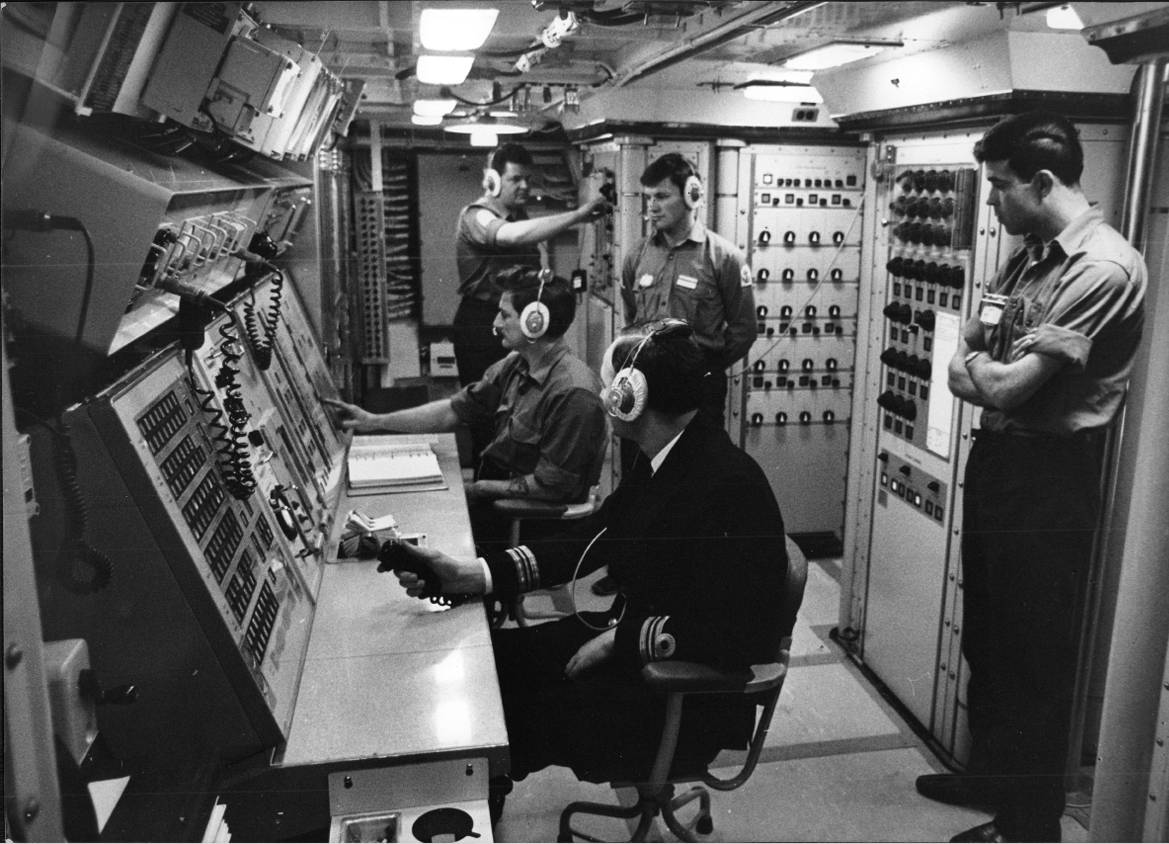

Still on 3 Deck, right outside 9 Berth (my bunk space), was AMS 1 (auxiliary machinery space), which housed a hydraulic plant, together with bilge and ballast pumps. Further aft, indeed as aft as you could go, was the missile control centre, where the missile trigger was kept. It was here, in conjunction with the control room, that the countdown to launch was managed. In this event, the WEO would sit and launch the missiles by firing a trigger, which was normally kept in a safe.

Inside the missile control centre as a practice drill is being carried out. Seated nearest to the camera is the WEO with his hand on the firing trigger, ready to go. (Associated Newspapers/Shutterstock)

Coming out of the missile centre was a ladder to the port side that went back on itself up to 2 Deck. Climbing it, you couldn’t help but stare – gobsmacked – into the missile compartment. Effectively the middle of the boat, it spanned three decks and was large enough to house 16 Polaris missiles, each 9.5m high, 1.4m in diameter and weighing 1,270kg. On the middle deck, those on watch kept vigil behind a roped-off area out of bounds to most of the crew. Here the temperatures of the missile tubes and the general compartment environment were monitored; the personnel also played a key role in the firing sequences of the missile tubes and the flooding of the tubes before launch. If a submariner breached this unauthorised area he’d be met with sudden and decisive truncheon blows and a subsequent thick ear, at best.

The health physics lab, also situated in the missile compartment, was where medical and radiological worlds collided, in the form of monitoring everyday life threats on board – testing oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen and CO2 levels throughout the boat to ensure they were within sufficiently safe limits to maintain life under the sea. The tech office, again situated in the missile compartment, housed thousands of different items to repair any defects that might occur on patrol (spare valves to operate the flushing mechanism for the toilets being one).

Exiting the missile compartment, heading aft, you came to AMS 2, the chief life-systems area of the boat, where the marine engineering mechanics maintained the ship’s atmosphere-purification equipment. On 1 Deck you had three CO2 scrubbers, whose job was to remove the dangerous CO2 exhaled by the crew from the boat’s atmosphere.

Sitting opposite the CO2 scrubbers were two electrolysers, which supplied oxygen to the crew by the electrolysis of water particles, producing oxygen. Also on 1 Deck was a CO/H2 burner, whose function was to remove carbon monoxide and hydrogen from the ship’s atmosphere, while on 2 Deck the toxins created by refrigerants or aerosols were dealt with by the Freon removal plants. Aerosols were banned, so the only acceptable alternative was roll-on deodorants, not that these helped much in preventing the rank pong of human sweat. On 3 Deck sat the two diesel generators that would be used in the event of a reactor shutdown or loss of nuclear propulsion. Also in AMS 2 were the de-humidifiers, whose task was to remove moisture particles from the boat, keeping condensation off the machines and their electrical supply.

Coming back up to 1 Deck, looking aft, you were faced with the reactor compartment. The reactor – effectively a latter-day steam engine – supplied steam through the heat generated by nuclear fission, which in turn produced the power driving the propulsion turbines and electrical generators to make the boat function. The only way to get aft of the submarine was via the tunnel across the top of the reactor compartment. When I first went through it as a wide-eyed 18-year-old, I was unsure as to whether I was actually passing into the reactor itself, so I just stood there outside the bulkhead, gawping into the tunnel, waiting like the new boy at school for someone to come through from the other side and show me how to enter. You have to open one bulkhead door, walk through and close it behind you, before going through to open the other bulkhead door. This was to minimise any potential radiation or safety breaches. The crew were protected against adverse radiation by primary and secondary shielding around the reactor itself, and then around the steam generator and main coolant pump. The big plus about the reactor was that it gave the submarine the ability to operate independently of the earth’s atmosphere for extended periods of time, as the generation of nuclear power needed neither oxygen nor air to make it work.

Once out of the tunnel you arrived in AMS 3, which was dominated by the manoeuvring room. In here, among all the dials that gave the impression of a mini power station, a team of engineers and artificers controlled all the nuclear, electrical and propulsion needs of the boat (the actual speed of the submarine was regulated here by the throttles). There were so many dials and controls it brought me out in a rash of hives when I first saw it; I thought I’d never remember them all for my qualification exams, but during my first patrol it grew to be the area I most enjoyed visiting. I found it fascinating to see how everything came together mechanically here, so far away from my job at the other end of the boat. I loved getting my overalls and boots on too, clambering about back aft and learning about nuclear propulsion, measuring pressures, flows, temperatures, precipitation, electrolysers and the like. It was all good, so long as I didn’t touch anything.

On 2 Deck of AMS 3 were generators and auxiliary motors; also found here was various equipment for safeguarding the running of the nuclear reactor. On 3 Deck lived the two turbo generators, and when the reactor was critical – i.e. up and running – they supplied all the boat’s electrical functions from the heat/power generated by the reactor.

Out of AMS 3 going further aft, you found yourself in the engine room, which housed the main turbines that drove the submarine. The final compartment in the arse-end of the boat was the motor room, where the electrical propulsion motor and clutch shaft were, doubling up as the aft escape compartment. It was also where the horribly cramped after escape hatch was situated. I used to have nightmares about being stuck back aft in a flood or fire and having to escape from the motor room – nigh on impossible as it was so claustrophobic; the mere thought of it was enough to affect the deepest of sleeps.

All the associated gear to turn the propeller was here, and considering that the propeller powered the boat along it was fairly quiet. I used to worry about the propeller’s shaft, as it penetrated the pressure hull to connect it to the blades of the propeller itself and had an extra sealing on it to prevent leaks. Any weakness in said sealing, and seawater would immediately start pissing into the compartment, filling the boat in seconds. The seal did actually leak some water, which would accumulate in the bilges and then get pumped overboard. The same could be said for other major penetrations of the pressure hull, like the torpedo tubes or the periscopes, and it could be fairly unnerving keeping watch in the control room if we were running at ultra-quiet stage, and thus fairly deep, with water coming down the periscopes and into the well.

Sometimes sailors – including myself – would be lowered into the well to clean up the water so the periscope itself wouldn’t be damaged. It was a tight fit, and I could barely move my hands in front of my body to wipe away the hydraulic oil. The periscope would be raised and the hydraulics isolated, and I would then have to clamber down on a flimsy rope ladder and commence the clean-up while hoping the periscope didn’t drop down on my head.

This was my living environment for three months at a time. I remember once diving in May and next seeing daylight in August, just shy of 100 days, a seriously long time to be running around cut off from the world. Miles and miles of pipes, high-pressure air, fans, pumps, nuclear weapons, an on-board nuclear reactor, 143 men, all stuffed within a pressurised hull and then dunked into the corrosive water of the world’s saltwater oceans. It’s a wonder any of us ever ventured in there in the first place.

* At periscope depth, the BRN mast supplies the submarine with instantaneous navigation information to lock down its latitude and longitude.

† Local operations plot.

‡ There was usually around 5 to 10 per cent of the crew who were studying for their dolphins on any given patrol.