Number Disconnected

‘Long and gloomy faces are in fashion.’

—Captain William Fell, 14th Submarine Flotilla

‘Shall we have a go then?’ asked Tich Fraser. The XE-3 was at the surface in Hervey Bay, 180 miles north of Brisbane. A warm tropical sun beat down on the submarine’s rough black casing. David Carey, Fraser’s first lieutenant, grinned. ‘Rather,’ he said excitedly.

‘Okay,’ replied Fraser. ‘Off you go then.’ Carey, dressed in blue working overalls, quickly pulled on a diving suit over his clothes and fitted a DSEA rig to his chest as Fraser submerged the boat into the azure sea. Carey clambered into the W&D and closed the door firmly, giving Fraser a little wave through the tiny inspection window. Little did Fraser realise that he would never speak to Carey again.1

*

The long voyage out from Scotland to Australia had taken the edge off the submarine crews’ skills. On 14 May 1945, while Captain Fell was in Sydney discussing operations with Admiral Fraser’s staff, the Bonaventure, under the command of Fell’s deputy Commander Derek Graham, had set sail from Brisbane and the XE-craft were finally all uncrated. The engineering crews had gone to work testing all systems and readying the submarines for the water while the operational and towing crews prepared to undertake more realistic training exercises in the Pacific waters off Australia.

While Captain Fell was in the Philippines, the submarines and their crews were put through an intense period of refresher training in Cid Harbour, a place chosen as being hopefully far enough from civilisation that the chances of Japanese aerial reconnaissance were nil. It was well known that some classes of Japanese submarine were fitted with small reconnaissance planes and that these aircraft had overflown Australian territory on several occasions.

Cid Harbour was one of the most beautiful places the Britons had yet seen, nestled on the coast of Whitsunday Island, 560 miles north of Brisbane on the Great Barrier Reef. The water was crystal clear, the surrounding beaches white sand and the land an intense green canopy of jungle. All six XE-craft spent days nosing around the harbour’s clear waters making dummy attacks on the Bonaventure, the divers practising sticking limpet mines on imaginary enemy battleships and aircraft carriers.

*

Captain Fell had bidden a warm farewell to Admiral Fife, or ‘Jimmy’ as he now preferred Fell to call him, on 22 May. The next morning at 5.00am Fell had landed from his temporary berth, HMS Maidstone, and set off with Fife’s aide-de-camp and Commander Davies, plus an armed guard, over 100 miles to Manila by road. There was one nervous moment when a loud bang had sounded close by their jeep and the vehicle had come to a sudden halt. The two US Navy guards had pointed their carbines menacingly into the surrounding jungle before realising that the sound had been caused by a burst tyre.2

Arriving at Manila Airport coated in fine white dust, Fell’s party were provided with a wash and lunch by an American admiral, while another senior officer told them that they could hitch a ride to Leyte in his own plane. The mood on the journey back to Australia was depressing. Fell had failed to secure a mission for his precious flotilla, ‘with practically no hope left for our continued existence as a fighting unit’.3

The night of the 23rd was spent on Peleliu, and the 25th on Manus, until Fell’s party finally arrived at Townsville, Australia late on 26 May. The last part of the journey had been particularly arduous. Dressed only in their summer uniforms, Fell and Davies had endured a cruise at an altitude of 14,000 feet over New Guinea’s Owen Stanley Range without oxygen or pressurisation.4 Worse was to follow. Waiting for them at Townsville was a Royal Australian Air Force Walrus seaplane that had been assigned to HMS Bonaventure. It was the only way to get to Cid Harbour. The Walrus had a bad takeoff into fierce crosswinds, Fell and Davies enduring two hours of severe turbulence before the pilot found the Bonaventure and executed a very heavy water landing that frightened his passengers half to death. Once the engines were switched off the pilot turned to Fell.

‘That was fun,’ he said, smiling as he pulled his leather flying helmet and goggles off. ‘It’s the first time I’ve ever flown a Walrus or landed anything smaller than a Catalina on the sea.’5 Fell looked at Commander Davies. They said nothing.

*

Teamwork at 14th Submarine Flotilla had been tightened up, and by the time an empty-handed Fell returned to the ship on 27 May, he was satisfied that his little unit was ready for whatever mission might yet come their way.6

The problem was that many of the men were not at all interested in the refresher training, considering that the flotilla had been dumped in Australia while the top brass tried to decide what to do with it. Morale had sunk quite low, according to Mick Magennis. There was a feeling that their efforts were wasted and that they, an elite force, were unappreciated and little understood.7

The one consolation to the rather glum atmosphere that pervaded 14th Submarine Flotilla in Cid Harbour was the diving. For the divers, the time that they spent beneath those beautiful Australian waters was memorable. Sub-Lieutenant Jock Bergius, a diver on Max Shean’s XE-4, felt that he had entered a wonderful world of colour and light. The divers swam silently over corals and sea plants while fish of every shape and colour flitted past. No prewar diver had ever been as at home beneath the waves as the XE-men had become. The DSEA breathing apparatus did not emit any bubbles like the rigs used by hardhat divers. The fish were not frightened away and the men could swim freely among them like aquanauts.8 But the idyllic locale soon began to lull the men into a false sense of security. As they were shortly to find out, Australia was to prove far from a safe posting. There were hidden dangers beneath those placid waters that were lying in wait for the unwary or the overconfident.

*

In late May 1945, the flotilla was struck another blow. A message arrived from Admiral Fraser at British Pacific Fleet headquarters in Sydney. Captain Fell was informed that as no work could be found for his XE-men and their ingenious machines, HMS Bonaventure would be proceeding to Sydney where she would ‘pay off’, that is, be put out of commission.

Fell stood on the Bonaventure’s bridge holding the signal flimsy in his hand for some time. Beside him, Commander Derek Graham watched his leader’s reaction with concern. Fell didn’t speak, just stared out to sea with a hard, flinty look in his eyes. Graham could imagine the riot of emotions that Fell must have been experiencing.

Morale among the XE-men, already low, sank even lower with the depressing news from Sydney. ‘Nobody interested,’ recorded Mick Magennis in his diary. ‘Have got the impression that we have been dumped here ’till they consider what they will do with us.’9 Magennis, like everyone else in the flotilla, had watched their commander dashing between meetings, hawking his wares and virtually ‘pleading for targets’. But, after so many disappointments, none of the men thought that missions would be forthcoming. It looked as though it had all been for nothing, a complete waste of everyone’s time. There would be no daring Far Eastern raid to rival the attack on the Tirpitz.

*

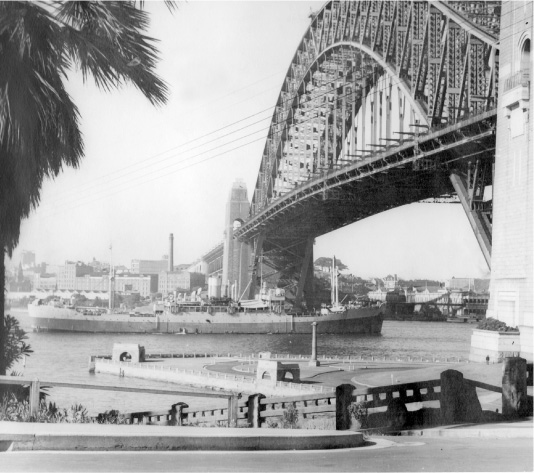

On 28 May, after talking to his ship’s company and the XE-men, and full of fresh ideas for future operations, Captain Fell attended a conference in Sydney chaired by Admiral Fraser.

The meeting started on 30 May and a conclusion was reached. It was decided to ask Admiral Nimitz one last time if he had any use for Fell’s unit and if the answer was in the negative, to disband the flotilla.10 Fell was then told to fly to Melbourne and discuss the Bonaventure’s future employment with Vice-Admiral Charles Daniel.

On 31 May, the last day of the conference, Fell was attending the usual staff meetings. Just before he made ready to leave for the airport he was suddenly called for. The Staff Officer (Intelligence), the US Navy’s Captain Claiborne, greeted a surprised Fell warmly in his office. The Americans, it seemed, were having difficulties in working out how to break Japanese submarine telephone communications between Malaya, China and Japan. Claiborne asked if Fell’s outfit could provide a solution, as it was imperative to cut the underwater cables that the Japanese used to connect their headquarters overseas with Tokyo. The request had come down from the very top of the American command.11

Fell couldn’t believe his luck – it was literally an eleventh-hour reprieve.12 Admiral Fraser gave his immediate approval for Fell, Claiborne and Davies to fly to Melbourne to collect more information on the proposed operations. In Melbourne, Fell was forced to spend the day in his scheduled meeting with Vice-Admiral Daniel discussing the paying off of the XEs and Bonaventure’s reassignment. Daniel knew nothing of the American request. Fell then sat down with the intelligence staff to examine the plan to cut the cables. It was all slightly surreal.13

*

The United States had broken Japanese diplomatic, naval and military codes; the resulting blizzard of decrypts was codenamed ‘ULTRA’. The Japanese had no idea of this enormous security breach. But with the contraction of the Japanese defence perimeter by early 1945, Tokyo was using undersea telephone cables to communicate with their forces on the nearby Asian mainland. The Allies’ flow of Japanese radio intercept intelligence had abruptly ended. It was now impossible to know Japanese plans in advance or monitor the deployment of their ships and military formations. If the cables were cut, the Japanese would be forced to return to communicating using the compromised radio codes, giving both the Americans and the British the crucial information edge. It could be the difference between speedy victory over the Japanese or a protracted slog into 1946.

As well as being vitally important to the United States, an operation to sever Japanese telephonic communications would also prove to be of great importance to Admiral Mountbatten, who was already planning the invasion of Malaya and Singapore. He could plot Japanese formations and reinforcements and monitor their remaining naval forces vis-à-vis Operation Zipper.

*

On 2 June Captain Fell was seated once again in front of Admiral Fraser’s desk in Sydney.

‘I gather from Captain Claiborne that the two of you now have a firm plan, Tiny,’ said the Admiral.

‘The operation to cut the Japanese telephone cables is exactly the sort of show my submarines were designed for, sir,’ said Fell to Fraser. Fell outlined his plan to Fraser, who listened patiently.

‘I realise you chaps are itching to have a crack at the Japs before the show’s over and I admire your persistence, Tiny,’ said Fraser when Fell had finished. ‘I’d like to see the plans in writing as soon as possible.’14

It took Fell, Claiborne and Davies three days to get everything worked out on paper. Fell immediately took the finished plans back to Fraser. After what seemed like an interminable wait Fell and his companions were ushered back into Fraser’s office. Fell noticed that the file containing his cable-cutting plans lay on Fraser’s desk blotter.

‘Well, Tiny,’ said Fraser, smiling, ‘a masterful piece of work. Your plan is approved.’ Fell was ecstatic. Now it just remained to persuade Admiral Fife at Subic Bay.15

Within the hour Fell was travelling back to the Bonaventure with the good news. He crossed his arms and turned to glance out of the small window beside his elbow at the shimmering sea passing by thousands of feet below. Now it was necessary for his flotilla to learn how to locate and cut undersea cables. How hard could it be? A smile formed on Fell’s lips, the smile of a man who has just been given a reprieve.

*

As soon as he returned to the Bonaventure on 6 June, Fell convened an orders group with John Smart, Tich Fraser, Max Shean and the other XE-craft skippers and their first lieutenants. Excited, he outlined the missions that Admiral Fraser had ordered him to plan. Firstly, Commander Davies laid out a large Admiralty chart of southeast Asia onto the Bonaventure’s wardroom table. The officers all crowded around.

After briefly outlining the general purpose of the missions, Fell pointed to the target areas.

‘We’ve to penetrate two separate areas,’ he said. ‘The Japs have the cables laid out in a triangular pattern. One line goes from Hong Kong direct to Singapore,’ said Fell, running his index finger down the map from the Chinese coast to the tip of Malaya. ‘And a second runs from Hong Kong to Saigon,’ he said, pointing at the mouth of the Mekong River in French Indochina, ‘then it runs on to Singapore.’16

The plan was for the cables to be severed at two distinct points close to the enemy coast. The first was off Lamma Island in Hong Kong, the second close to the entrance to Saigon’s Mekong River. Though only two XE-craft would be used, no decision had yet been taken concerning which ones would be chosen, explained Fell. Everyone would train for the job, and Fell would select the two ablest crews for the missions once he had evaluated their performances. Fell would write cheerfully to Admiral Fraser, predicting his return to the Philippines and a meeting with Admiral Fife: ‘I am eagerly looking forward to another acutely uncomfortable journey.’17

But the first, and biggest, challenge was working out how a submarine telephone cable could be grabbed by an XE-craft. Fortunately the British knew exactly where the cables were located. The Bonaventure’s navigator had produced charts from his library that showed the position of the cables off Saigon and Hong Kong. The detail was impressive. Navigation would have to be precise, but Fell knew that his men were more than up to the task.

Fell had also had the forethought to bring with him a Cable & Wireless engineer from Manila to help settle some of the technical issues that the mission presented.

‘If a cable ship were to do this job,’ said the American civilian expert to the assembled XE-craft officers, ‘she would drag in deep water with a large grapnel, haul the cable to the surface with a powerful winch and then cut it.’

‘Well, we already have the last part of the operation covered,’ said Fell. ‘We use hydraulic cutters to make holes in anti-submarine and anti-torpedo nets. I don’t think we would face any problems slicing through a cable.’18 Fell turned to Chief Engine Room Artificer Ron Fisher, one of the Bonaventure’s senior technical crew. ‘Fisher, I’d like you to start work on modifying the cutters to tackle the much thicker telephone cables. The XO will give you the cable dimensions.’

‘Aye aye, sir,’ replied the middle-aged chief petty officer. The Bonaventure’s fully equipped workshop and highly trained artisans could deal with most requests.

‘What about grabbing the cable itself?’ asked the engineer.

‘We don’t have a thing, I’m afraid,’ sighed Fell. ‘These submarines were not designed with this kind of job in mind. We’ll have to put our heads together and create something.’

‘Sure,’ said the engineer, adding, ‘the grapnel could be something shaped like a large anchor.’

‘What sort of depth should this be performed at, sir?’ asked Lieutenant Shean.

‘At least 30 feet, but ideally much deeper,’ remarked the engineer.

Fell grimaced. ‘Depth is a problem, old boy. Our divers can only work safely at a maximum depth of 30 feet.’

‘Then you have a problem, Captain,’ said the American engineer, peering at the charts with the cables clearly marked upon them. ‘Deeper is better because beyond 50 feet the bottom sediments no longer move. You could locate the cables easily at between, say, 50 and 100 feet. It’s going to be darn difficult to find the cables in shallow water because they will be buried quite deep in all the crap on the bottom.’

‘Fifty feet is somewhat beyond our safety margin, I’m afraid, especially if the divers are going to be working on the cables for more than even a few minutes,’ said Fell. ‘Ideally it’s going to be no deeper than 30 feet for any extended period. Time is a big factor in all of this. I’d not want them operating at their maximum depth for more than 30 minutes.’

At the conclusion of the meeting Fell, though a little disappointed by how complex the operation was rapidly becoming, nonetheless suggested to his men that they start thinking about a design for a grapnel. Each crew was ordered to design something. Arrangements were made for trials to be made on a wire hawser laid on the harbour bed by the Bonaventure’s crew. This would simulate a cable and be used to test the different designs.19

Nearly everyone opted for a kind of reef anchor, all except the mechanically creative Shean. He and his crew came up with what turned out to be the most efficient design. Christened a ‘flatfish’ grapnel, it comprised a diamond-shaped steel plate, three feet long, with fins shaped like halves of a crescent moon welded top and bottom.20

‘The diamond is towed by chain,’ said Shean during a presentation of his design. ‘It lies flat on the seabed while the lower fin digs into the mud. The second fin will dig in if the grapnel is laid the other way up.’21 It was important that the design be just right, for, unlike using a large dredging vessel or cable cutter, the XE-craft had only a little Keith Blackman 30hp electric motor with which to drag the grapnel through the mud while the submarine was submerged.22

*

At this point, with missions on the cards, Captain Fell decided to put some of the officers through an ad hoc survival exercise. After all, if anything went wrong on either of the missions, some of them could end up stranded ashore in very hostile territory. Shean took XE-4 and her crew close to Hazelwood Island before mooring the submarine and using an inflatable dinghy to reach dry land. They were equipped with one 24-hour ration pack, a water bottle and a poncho per man, together with one shotgun and some fishing lines. Fell ordered them left to fend for themselves for five days.23

The party’s food was quickly supplemented when one of the officers shot a very elderly goat. They lived mainly on this rather tough meat and rock oysters. On the evening of day three an accident occurred. While the party was scavenging for oysters in the shallows in a flat area behind a coral reef, Jock Bergius trod on a stingray. The startled fish stung him on the ankle. Bergius was in agony and Shean became concerned for his welfare. Shean, ERA Ginger Coles and Sub-Lieutenant Ben Kelly carried Bergius over to the dinghy. It was pitch dark when, after boarding the XE-4, they started out for the unlit Bonaventure. Navigating through deep water, Shean used the Aldis lamp to warn the Bonaventure to stand by. ‘Bergius stung by stingray. Coming to starboard gangway,’24 he flashed in Morse code. Bergius, limping in agony, refused to lie down on a stretcher and instead hobbled painfully under his own steam to the quarterdeck. He was determined to show what stuff Scots were made of.25 For a day, Bergius was semi-conscious, and Coles never left his side, carrying out primitive but efficient first aid using a tourniquet and much blood-letting to get rid of the poison in Bergius’ left side.26

Fell spoke briefly with Shean, who agreed to return to Hazelwood Island to complete the exercise. The nocturnal visitors, Fell wrote, gave an appearance of being ‘already half way back to the state of aboriginals’.27 Once safely returned to the Bonaventure on day five, all the officers professed to have enjoyed themselves, but no one approached the flotilla second-in-command with a request to be included in the next similar exercise.

*

While Shean, Fell and the other XE-men had been labouring to perfect a technique for underwater grapnelling, the strategic situation had continued to evolve. The most momentous development had been Germany’s surrender on 8 May 1945. Just over a month earlier the US Chiefs of Staff had rejected Lord Mountbatten’s planned invasion of Malaya and Singapore, Operation Zipper, even though planning was by now well advanced.28

Mountbatten had argued forcefully and cogently that the longer the delay, the stronger Japanese defences became in Malaya, and the greater the sufferings of Allied civilian internees and prisoners-ofwar. The Americans relented soon after and the operation was back on, but Zipper was still hamstrung by a lack of light fleet carriers to provide air support over the landing beaches. But Mountbatten, like the erstwhile leader of 14th Submarine Flotilla, simply refused to give up the operation, regardless of the logistical and equipment shortages that were forced upon him by London and Washington. By hook and by crook he managed to assemble nine aircraft carriers, two battleships and an armada of cruisers, destroyers and landing ships even though First Sea Lord Cunningham continued to divert many major vessels to Admiral Fraser’s British Pacific Fleet off Okinawa.29 So, while Mountbatten lobbied, negotiated and argued Zipper’s merits, 14th Flotilla in Australia began training for a mission that was, unusually for such a contentious theatre, in both the British and American interest, and requiring support from both nations. It was about the last mission that Fell or the XE-craft commanders had expected to receive, but beggars can’t be choosers.

*

‘Make your depth 20 feet,’ ordered Lieutenant Fraser, XE-3 submerging from the glassy surface of Cid Harbour into the crystal-clear depths below. The target once again was a steel hawser that had been laid on the seabed to mimic an undersea telephone cable. Mick Magennis was already struggling into his diving suit beside the Wet and Dry Compartment, preparing himself for another practice at cutting the cable.

‘Twenty feet, Tich,’ sounded off first lieutenant David Carey.

‘Right, stand by diver,’ ordered Fraser, turning to the night periscope for a quick look underwater. ‘Okay, Magennis, away you go, and good luck,’ said Fraser as the diminutive Magennis went through the small door into the W&D chamber. Inside the control room the other crew could hear Magennis turning valves and flooding the compartment. Fraser peered through the chamber’s little window and saw Magennis breathing steadily into the DSEA bag as the water rose around him.

Fraser watched through the night periscope as the W&D hatch came open and Magennis emerged awkwardly.

‘Diver out,’ said Fraser, his eyes never leaving the periscope. Magennis turned briefly to the periscope and gave Fraser the thumbs-up signal before swimming over to the stowage compartment outside the submarine where he selected the grapnel that was attached to a 50ft length of stout manila rope. Magennis dropped the grapnel, letting it fall to the seabed, the rope paying out behind it. Then he re-entered the W&D and flooded down.30

Once Magennis was safely aboard, Fraser submerged XE-3 to within ten feet of the bottom, Carey adjusting the boat’s trim with the compensating tanks fore and aft. This depth would be maintained by carefully watching the sounding apparatus in front of Fraser’s position in the control room. Slowly, the submarine crept forward until it was brought to a sudden jerking halt as the grapnel caught on the cable, pulling it several feet off the seabed.

This was the signal for Magennis to enter the W&D again. But first, Fraser landed the submarine on the seabed. Once Magennis was outside the XE-3 he collected the special hydraulic cutters normally used to cut through anti-submarine nets, followed the rope to the grapnel and made his cuts. When he had finished he felt his way back along the rope to the XE-3, stowed the cutters and reentered the W&D. It was a simple enough process in clear water, and against a cable that was not buried by silt, glutinous mud or sand. But divers had to go slow. Over-exertion even at safe depth was dangerous when working on pure oxygen.31

*

On 12 June the XE-craft were hoisted aboard the Bonaventure. The next day she sailed from Cid Harbour to Townsville to embark stores and provisions.

Training shifted to Hervey Bay on 15 June, where there was a disused telegraph cable. This would more closely simulate the real conditions that the two selected crews would encounter in their missions against the Japanese. The cable, stretching for a mile, was up to 50 feet deep in places and partly buried in silt and mud. It would test the divers to the limits of their endurance.

On 17 June, Mick Magennis was not available to dive. Instead, Tich Fraser took aboard a spare diver from one of the passage crews. While XE-3 was still surfaced and close to shore the diver suddenly reported to Fraser that there was something wrong with his equipment. He said there was a defect in his breathing apparatus. Fraser took the DSEA from him and tested it himself. He could find nothing wrong with it. But the reserve diver was adamant – it was defective and he wouldn’t dive. Fraser had no choice but to send him back in the safety boat to the Bonaventure. After all, if there were something wrong with the equipment, the diver would be the one to suffer, not Fraser.32

Fraser and his best friend David Carey were determined to continue with the exercise. When Fraser suggested that Carey have a go, the younger officer jumped at the opportunity. Once Carey was dressed and inside the W&D, the compartment was flooded and Fraser took his position at the night periscope to watch his friend. Carey disappeared off the stern of the submerged XE-3, following the line down to where the grapnel had snagged the cable. As Fraser watched, his friend reappeared and gave him the thumbs-up sign. Kicking his swim fins, Carey moved over to the stowage compartment and collected the hydraulic cutters before swimming back down the rope. After a few minutes Carey reappeared, stowing the cutters and giving Fraser another thumbs-up. Fraser glanced at the depth gauge – 47 feet.

‘Prepare to surface,’ ordered Fraser, as Carey re-entered the W&D after stowing the grapnel. Fraser stood by while the valves began to open as Carey prepared to flood down. Suddenly, with a bang, the hatch to the W&D flew open and Carey shot out. Fraser pressed his eyes against the night periscope and saw Carey atop the submarine’s casing, giving him the thumbs-down sign.

‘Surface the boat!’ yelled Fraser. Something was dreadfully wrong. As the little submarine broke the surface, Fraser was watching his best friend carefully through the night periscope. But before Fraser could open the main hatch Carey suddenly dived over the side into the ocean and disappeared beneath the surface.33

He didn’t reappear.

The crew of the original X-craft submarine X-24 photographed on the bridge of the towing submarine HMS Sceptre after their unsuccessful mission to sink the German floating dock at Bergen, Norway, 15 April 1944. They would all play important roles in the XE-craft missions in the Far East. Pictured, from left to right: Sub-Lieutenant Joe Brooks, who was appointed first lieutenant of XE-4 until his replacement by Ben Kelly; Lieutenant Max Shean, later commanding officer of XE-4; Engine Room Artificer 4th Class Vernon ‘Ginger’ Coles, engineer on XE-4; and Sub-Lieutenant Frank Ogden, who was passage crew skipper for XE-3 during Operation Struggle, July 1945.

Some of the officers and men of 14th Submarine Flotilla photographed aboard the depot ship HMS Bonaventure in Scotland, late 1944.

HMS XE-1 surfaced during training in Scotland. Lieutenant Jack Smart stands on the casing gripping the raised air induction trunk, or schnorkel, for balance.

An XE-craft approaches the practice anti-submarine boom in north-west Scotland before submerging to allow the diver to cut through the net.

Captain William Fell (right), commanding officer of 14th Submarine Flotilla, with his second-in-command, Lieutenant-Commander Derek Brown, HMS Bonaventure, 1945.

Acting Leading Seaman James ‘Mick’ Magennis (left), XE-3’s diver, with his commanding officer Lieutenant Ian ‘Tich’ Fraser.

The crew of HMS XE-5 photographed in Scotland before departure for the Far East. From left to right: Sub-Lieutenant Beadon Dening, Lieutenant Herbert ‘Pat’ Westmacott, Sub-Lieutenant Dennis Jarvis and Engine Room Artificer 4th Class Clifford Greenwood.

The Davis Submarine Escape Apparatus (DSEA), an early rebreather modified for use by commando divers.