At first, she was a great mom, spending all of her time caring for her babies. She fed them, kept them warm, cleaned the home, protected them from harm, and touched them in ways that made them feel calm and safe. If anything threatening came near them, she was ready to attack, to protect them with all she had, even to the death. Intriguingly, before she had her babies, she had no interest in being a parent. In fact, she found infants quite annoying, certainly not a source of pleasure. After she got pregnant and gave birth, however, everything changed and she was preoccupied with being close to them and taking care of them.

In fact, she found the process of mothering extremely rewarding, preferring it to all other rewarding things in life. With her attention now riveted on her babies, she could read their signals instantly and know what they needed. And if they somehow got separated from her and she heard their cries, she searched for them relentlessly until she found them and brought them home where she then gave them extra loving care.

But then, something happened inside her, something she couldn’t understand, and soon she stopped being this great caregiver. She let the home go to pot and resisted the attempts of her babies to get her attention and to let her know their needs. They began to lose weight, becoming frightened, hovering around her, not knowing what to do to bring back the mom they knew. Completely dependent on her care, they were now in deep trouble. Then, just in time to bring them back to life, she regained her motivation to be a mom and resumed all of the caring behaviors she had shown before. She emerged from her mysterious “blocked care” and with her nurturing powers restored, saved her little ones from sure death.

This poignant true story of parental love, lost and regained, captures the essence of blocked care. As you may have guessed, the mom here is not a human parent; she’s a cute little white lab rat, one of the thousands who have taught us so much about ourselves and helped to improve our lives in so many ways. Yes, these little rodents tend to be great parents, dedicating themselves to the care of their young until their “kids” reach maturity after a long journey in rodent time of 20-some days. By the time their offspring reach maturity, the tired moms actually show a preference for other rewarding things in life over being with their now self-sufficient young adults. Sound a bit familiar?

The mom in our story stopped parenting for a while because those clever brain scientists temporarily “knocked out” the regions of her brain that are now known to be crucial to caregiving. Then, when they removed the block and restored the functioning of these key brain regions, she was able to parent again, regaining the core motivation she needed to override an otherwise natural aversion to infants. When these core brain regions devoted to parenting were turned back on, the mom regained her lovely obsession with caring for her babies, rediscovering the pleasures of being a mom. With her care system restored, she again became preoccupied with them in ways that allowed her to tolerate all of the stress and hard work involved in raising them to maturity.

In this vignette, the care system was knocked out by the scientists; in people, the core parenting system can be suppressed in a number of different ways. A dramatic example of this care-suppression process is seen in postpartum depression. Parents who develop postpartum depression find themselves unable to feel loving and empathic toward their children, despite having an intense desire to nurture them. Postpartum depression is not induced by parent–child interactions in the way that blocked care is, but rather is an internal process having something to do with the brain chemistry that normally primes the maternal brain for parenthood.

In general, depression and anxiety are care-suppressing conditions, affecting the parts of a parent’s brain that are essential for experiencing nurturing feelings and caring about other people. Parents with closed-head brain injuries affecting the frontal lobes are likely to have problems maintaining good connections with their children. In addition, parents who are on the autism spectrum, including parents with Asperger disorder, often experience some difficulty with attunement and empathy as a result of the atypical functioning of the parts of the brain involved in “people processing” and nonverbal communication. However, in our model of blocked care, the primary source of interference with caregiving is unmanageable stress associated with the experiences of parenting and, in most cases, some aspects of the parent’s own attachment history.

Blocked care takes different forms, depending on the source and duration of the stress parents’ experience. Below, we describe four types of blocked care:

1. chronic

2. acute

3. child specific

4. stage specific

Rebecca spent the first 2 years of her life in the care of her mother and father. Her parents often argued and sometimes their arguing ended violently, with her mother being slapped and her father leaving home for days at a time. Before her first birthday, Rebecca had learned to suppress the terrible feelings that were triggered by her parents’ angry voices and faces. All she had to do was freeze and shut off her mind, going numb as if she were playing dead. She learned to dissociate without even knowing she was doing so.

Her mother finally left her father and raised Rebecca herself, with the sporadic involvement of several different men who came and left over the years. At the age of 17, Rebecca met Billy and began having sex, which was the first time she had felt safe, for a little while, with another person. She soon got pregnant and the hormonal changes of the pregnancy also stirred feelings of love and warmth inside her that had long been suppressed. Billy was out of her life when her beautiful baby, Eric, was born. From the apartment she had been sharing with three friends, Rebecca moved back in with her mother.

At first, just after Eric was born, Rebecca felt a deep, all-encompassing love for him and a calmness she had never experienced before. But soon, when he would cry and flail his arms and legs, resisting her efforts to comfort him, she began to feel overwhelmed, angry, and stressed out. Her initial loving feelings began to erode, suppressed by her anger and a feeling of being trapped by parenthood. She began to tune out Eric when he sought her attention, using the old strategy from her early years of shutting out the world and numbing her feelings. Gradually, Eric stopped seeking her attention as much and turned, instead, to her mother (his grandmother), who became his “go to” caregiver. Sadly, despite all of Rebecca’s initial expectations of giving and receiving unconditional love when Eric was born, her capacity for nurturing her son seemed to have disappeared. She had developed “blocked care.”

Rebecca needed help from someone who could understand how well-meaning parents can lose their motivation to care for their children. She needed a therapist who could help her feel safe revealing her negative thoughts and feelings about Eric, someone with a deep understanding of the dynamics of blocked care and a roadmap for helping her recover her capacity to nurture Eric. Rebecca knew she wasn’t “supposed” to feel the dark feelings she was experiencing about Eric and about being a parent, but she didn’t know what to do with these feelings and the shame that lay just beneath the surface of her anger and resentment. She had never experienced being listened to and accepted without judgment and had no basis for trusting Jane, the home-based therapist who was assigned to her case when Eric’s poor behavior at preschool drew the attention of family services.

When a parent has experienced unmanageable levels of stress beginning very early in life, blocked care stems from a combination of a poorly developed care system and an underdeveloped self-regulation system. In this scenario, the core caregiving domains of approach, reward, child reading, and meaning making are underdeveloped, making the basic caregiving process difficult to activate. Meanwhile, the top-down Parental Executive System is also underdeveloped, creating a dual-circuit problem that makes chronic blocked care particularly complex.

Let’s look at how each of the five parenting systems may be affected in chronic blocked care. We will consider the effects on Rebecca’s brain of growing up in adversity and then trying her best to parent Eric before she had a chance to develop the brainpower she needed.

Rebecca’s early childhood forced her to play defense around her parents, overusing her right-brain harm avoidance system while having little chance to develop her social approach system. Her oxytocin system was not working well, due to both underdevelopment in childhood and her current stress. Instead of releasing this calming chemical when interacting with or even thinking about Eric, Rebecca was releasing stress hormones and activating her defense system, which kept her feeling insecure and uncomfortable around Eric and as a parent.

Similar to the suppressing effects of stress on Rebecca’s approach system, her reward system was underdeveloped due to the effects of early childhood adversity on the development of her dopamine system. Her reward system was geared toward immediate gratification due to spending her childhood in survival mode. Her need to find pleasure in “quick fixes” set her up for both hypersexuality and drug abuse, and she found herself caught up in brief sexual encounters, drinking, and pot smoking, unable to defer pleasure enough to find satisfaction in parenting Eric. As with many people exposed to adversity early in life, Rebecca had a heightened risk for addiction partly because of (1) underdevelopment in the prefrontal regions that could help her to regulate her impulses, and (2) partly because chronically high levels of stress hormones alter the sensitivity of dopamine receptors in the nucleus accumbens and orbital cortex—regions that are critically important to processing rewarding things in life (Winstanley, 2007). The more immediate activation of these brain regions by drugs and sex was blocking the naturally rewarding aspects of parenting. Plus, due to the tensions between Rebecca and Eric, many of his responses to her were now negative, defensive, and even aggressive, reinforcing her negative and defensive feelings towards him.

In terms of her child-reading system, Rebecca had learned very early in childhood to be hypervigilant for facial expressions and tones of voice that signaled impending aggression, and this hypervigilant style caused her to react extremely rapidly to any “negativity” in Eric’s nonverbal communication. She was quick to feel threatened by the least signs of anger in Eric’s eyes or voice and would go into a preemptive state of defensiveness and anger herself, short-circuiting any further processing of Eric’s experience in the moment. Thus, Rebecca did not read her son’s unique nonverbal cues very well and did not really get to know him. Instead, her amygdala-driven hypersensitivity to the least signs of rejection from Eric was foreclosing the possibility of understanding her son.

Rebecca’s meaning-making efforts, in her survival-based narrative about being a parent, were understandably quite negative. She had fixed beliefs that she was a bad mother and that Eric was an ungrateful child, essentially a story of victimhood in which she blamed both Eric and herself. Because her feelings of being a bad parent were intolerable to her, triggering deep shame, she rarely let herself think about her relationship with Eric, blocking any reappraisal of her strongly-held negative beliefs. Although her anger and resentment protected her from her shame and an underlying sadness about the deep misattunement in their relationship, these care-suppressing feelings also suppressed Rebecca’s potential to change her mind about Eric, to see him in a new light.

Finally, at the core of Rebecca’s parenting problems was a poorly developed executive system due to the stress she had experienced in early childhood, during the sensitive period for constructing those all-important connections between her prefrontal cortex and her limbic system. A poorly developed executive system meant that she had little capacity to pull back from her initial defensive reactions to Eric, and reassess; instead, she would quickly lose her cool and have no effective way of putting on the brakes and recovering from these lapses in self-regulation. Also, Rebecca became a parent before her brain had fully matured, forcing her to try to deal with the challenges of raising Eric without the benefit of the prefrontal cortex power that comes with more neurobiological maturity.

Things were going well between Alicia and her 12-year-old daughter Tammy, until Alicia’s mother died suddenly from a massive heart attack. Alicia’s mother was her “rock,” and losing her in this way was a huge shock to her, sending her spiraling into grief that took all her energy to manage. Her strong grief reaction quickly began to interfere with her parenting and her connection to Tammy, who was now a young teenager, already trying to weaken her dependency on Alicia. Alicia’s lapses into extreme sadness took her further away from Tammy just at a time when Tammy both needed her and didn’t want to need her. Alicia was experiencing an acute suppression of her motivation to parent.

Compared to Rebecca and the chronic blocked care she exhibited, Alicia had fairly well-developed systems for parenting Tammy and for finding pleasure in that role. Before her mother died, she was quite good at reading Tammy’s communication; they shared thoughts and feelings and experienced being heard and understood.

Alicia’s narrative about herself as a parent, before she developed acute blocked care, was generally positive. She thought of herself as a good and loving parent and of Tammy as a good kid. She connected her parenting to the way her mother had cared for her and saw herself as part of an intergenerational tradition of good mothering. In the aftermath of her mother’s death, Alicia was struggling to regulate the intense feelings she was experiencing; much of the time, she found herself outside of her coping range. This acute reaction to extreme stress was temporarily suppressing her prefrontal functions while overactivating her limbic system. Although different in nature from the chronic blocked care scenario we see with Rebecca, Alicia is still in need of help to recover from the care-suppressing effects of the stress she is experiencing, a process that is putting her at risk for developing a more enduring type of blocked care.

After years of trying to have their own child, Janet and Jim finally adopted Kim, an adorable Korean girl who had spent her first 2 years in foster care after her birth mother had given her up at birth. Janet and Jim were bursting with joy when they arrived home with Kim, eager to experience the rewards of being loving parents. It wasn’t long, however, before they both began to experience extremely unsettling feelings of deep disappointment and an almost unspeakable sense of having been misled, almost duped. Kim rarely smiled at them and often went into a rage over the least little things. She resisted their hugs, but later would jump on them when they weren’t looking and cling as if for dear life. Their expectations of what parenting was going to be like were being violated everyday, in multiple ways. By the time they had had Kim for a year, they were both feeling resentful and were having great difficulty feeling empathic toward their complicated daughter.

Janet and Jim were developing what we call child-specific blocked care. Although they were both caring people with good potential for parenting, their adopted child’s lack of secure attachment behaviors and ongoing reciprocal interactions with them placed them at risk for gradually responding in a defensive manner that would create blocked care toward this child. This risk might have been reduced if they had been given preadoption education about the difficulties that their child might show in developing an attachment. It also might have been reduced if they had been more aware of their own attachment issues and had had a chance to work on any unresolved potential “hot buttons” from their own histories. However, because the Parental Reward System is such an important aspect of the natural parent–child bonding process, their child’s poor response to their caregivng would still place them at some risk for developing child-specific blocked care. Their expectations were understandably not realistic about what it would be like to parent a child who had been forced to “play defense” early in life. Their caring feelings were eventually suppressed by the self-defensive feelings of rejection and anger they experienced from trying to parent a child who could not yet feel safe with them.

Under certain circumstances a parent may be able to provide very adequate care to one child while being unable to provide the same level of care to another child. This may occur:

• When one child is closely associated with an acute stressor from the parent’s past so that the child’s presence activates the defensive system called into play by that stressor. This might be the case if the child’s appearance, temperament, behavior, or mannerisms remind the parent of someone else (e.g., his own parent or ex-partner).

• When one child consistently does not respond in a positive, reciprocal manner to the parent’s caregiving behaviors. When these caregiving behaviors are ineffective, their failure is experienced as being extremely stressful, defensive systems are activated, and caregiving begins to shut down. There is a risk of this form of blocked care if the child manifests autistic features or if the child’s attachment behaviors are inhibited or disorganized due to his or her history of trauma or loss. This may occur with a parent who is providing care for a foster or adopted child.

Child-specific blocked care might well become a source of extreme acute stress that could engender a more enduring, habitual form of blocked care if it goes on for an extended period of time. Although initially the parent may have been able to provide ongoing care to other children when his or her care for one child was a failure, eventually the stress of the child-specific blocked care places the parent at risk for acute blocked care for the other children as well.

Charlie had really enjoyed his relationship with his son Josh while Josh was an exuberant, playful preteen. They would wrestle together on the sofa, tickle each other, acting in many ways like “buddies.” They shared similar interests in the outdoors and sports and often went off together for the day or talked into the night. Then, something changed; Josh entered puberty and didn’t want to wrestle anymore. He was spending more time texting his friends and less time being interested in being around his dad. Charlie began to feel rejected and unappreciated—feelings he had had as a kid when he could not get his dad to pay attention to him. These feelings were growing now and making it hard for Charlie to like Josh anymore. They began to argue a lot, and Charlie found himself losing his temper in ways he hadn’t when Josh was younger and playful. Charlie was struggling to stay parental following this shift from the little boy to the “tween” stage of Josh’s development, and he was finding himself knee-deep in stage-specific blocked care.

Many parents are able to provide extensive care to their child when the child is engaged, receptive, and agreeable. These parents may have no trouble caring for their children when they exhibit a mellow and friendly temperament and seldom show any resistance to their guidance or directives. However, most children go through stages where they become more argumentative and independent for a time, and do not respond to their parents’ caregiving behaviors. During these stages the child is not interested in a reciprocal relationship with his or her parents; rather, the child’s focus is more on his or her independent activities and on peer relationships.

The “terrible twos” is one such common stage. Another is adolescence—or hopefully, more the early stage of adolescence, before the teenage brain starts to develop more prefrontal power, which then helps the teen start to emerge from the intensively egocentric stage of brain development that is normal during the earlier teenage years. In early adolescence, the limbic system becomes much more active, driving emotionality, at the same time that the prefrontal cortex is not yet mature. As brain scientists like to say, this is like having a heavy foot on the gas pedal while your brakes don’t work very well.

When the child becomes habitually oppositional to, or withdrawn from, the parent, the parent is at risk for experiencing stage-specific blocked care. The lack of reciprocity in the interactions is one factor. Another is the parent’s intense experience of rejection, which is likely to trigger a defensive state within the parent. Many parents are at risk of entering such a state whenever they discipline their child. We often discipline our kids in ways very similar to the way our parents disciplined us. For many parents, their early experiences with being disciplined were likely to contain anger, threats, or a narrow behavioral focus with little openness to their own experience of being disciplined. Similarly, some parents have difficulty initiating relationship repair with their child following a conflict. When the relationship is not repaired, it is difficult for the parent to actively use all five domains of caregiving.

In parents who had to play defense much of their lives, their neuroceptive threat detection system (described in Chapter 1) is likely to overdetect threats from other people. In chronic blocked care situations, the parents’ amygdalas, especially on the right side of the brain, are likely to be enlarged and exquisitely sensitive to potential threats. This sensitivity causes the defense system to work overtime in an effort to keep them safe in the way this same system did when they were little children.

Even as the amygdala tends to grow and become more reactive from exposure to adversity, other regions of the brain that are essential to staying grounded and putting things into perspective tend to shrink from exposure to chronic or acutely excessive stress (Admon et al., 2009). These include regions of the prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex that are so vital both to keeping our lids on and to the capacity to see beyond our defensive reactions. This stress induced brain suppression process also affects the hippocampus, that brain region that is essential for memory, learning new things, making new brain cells, and regulating stress (Fuchs & Flugge, 2003; Heim & Nemeroff, 2002).

As we’ve seen, the amygdala not only triggers the alarm system; it also helps to make memories, very enduring memories, of things in life that surprise us with their intensity, either positively or negatively. It does this by rapidly linking or associating previously emotionally neutral aspects of the environment with the physiological reactions of joy and pleasure or with the physiological states of self-defense, of fight, flight, or freeze. Simply being exposed again at any time in life to these reward-conditioned and threat-conditioned cues can reinstate both the pleasurable and defensive reactions we had earlier in life, before we are even aware of having been triggered by something. Once the right-brain defense system gets tuned to an unsafe environment, it tends to keep setting off the alarm system later in life when other people come close, causing frequent false alarms that make it difficult to stay connected and engaged with other people, even when trying to do so (Pollak, 2003).

False alarms are likely with this rapid, preconscious process because the quality of information to which the amygdala is responding initially is extremely rough, lacking in detail and in context. Although the amygdala soon receives more highly processed information both from sensory regions and from areas of the prefrontal cortex that are in close communication with it, the first appraisal system can short-circuit further processing and lock us into a survival-based state of mind and body.

Young children, by definition, are much more “amygdaloid” creatures than more mature people. However, we retain this quick appraisal and reaction system throughout life and at any age, we could have an amygdaloid, “limbic” moment if we encounter something very novel and very arousing, either positive or negative. We can also have these reactions when a strong memory of an experience from any time in our lives gets triggered. This is especially true of unresolved traumatic memories. When these memories are triggered, the amygdala on the right side of the brain becomes very active and can reinstate the pattern of brain and body arousal that took place during the actual traumatic event. Because the amygdala has so-called back projections to the areas that send it information, it can “revivify” a memory, bringing the sensory experience of that memory back to the level of intensity of the original occurrence (Vuilleumier, 2009).

This is the neurobiological process that gives rise to flashbacks and the sensory experience of not just recalling something, but of reliving it. Parents, then, who have unresolved memories of painful, frightening, or shaming experiences are prone to being triggered by their interactions with their children into unparental states of mind, during which they lose touch with what is really happening in the parent–child relationship in the moment. These parental “disappearances” or “out-of-the-blue” emotional reactions are inevitably upsetting to a child and can even be traumatizing.

Unfairly, then, parents who grow up in environments that are very stressful and that engender strong feelings of fear are likely to have more sensitive limbic alarm systems than parents who grow up in safety. Early childhood is a time when the limbic system is learning about the nature of interpersonal relationships. In this process it is also getting “tuned” to a certain level of reactivity or sensitivity to different kinds of social situations—and especially to the nonverbal communication that signals approachability or threat in others. Parents from unsafe childhoods are likely to experience limbic reactions to their children that are inconsistent with their intentions as parents. Implicit defensive reactions caused by limbic “false alarms” can make it very difficult for a parent to stay open, present, and attuned to a child in the moment. This is one of the most powerful reasons why we say that parental development begins in early childhood with the type of caregiving environment available to the parent-in-the making.

When stressed out, parents do not use all of the prefrontal cortex. In particular, the middle and topmost regions are likely to shut down and be out of commission, whereas the lowest region, the orbital cortex, may function partially, especially the part of the right orbitofrontal cortex that responds to things that are threatening or punishing. The middle and upper regions of the prefrontal cortex turn on only when parents are emotionally regulated enough to step back and take a longer, slower, deeper look at what is going on, both within themselves and in their children (Banfield et al., 2004). In stressed-out survival-based brain mode—that is, in a state of blocked care, with the higher prefrontal regions suppressed—the vital functions of self-awareness and self-monitoring are offline, along with attunement to the child’s thoughts and feelings, and the processes of conflict resolution and problem solving.

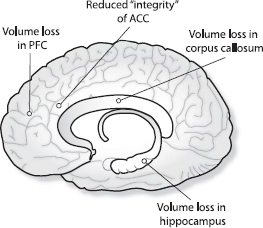

Early childhood adversity in the form of abuse and neglect can have a negative impact on the very regions of the brain that are so important for healthy social and emotional functioning (DeBellis, 2001). The affected regions, as seen in brain-imaging studies of adults who experienced abuse or neglect as children, include the prefrontal cortex, the hippocampus, the anterior cingulate cortex, and the corpus callosum (which connects the two sides of the brain and helps the right and left hemispheres “talk” to each other), as shown in Figure 3.1 (Teicher et al., 2003).

Effects of early childhood adversity on the brain from a study of adults abused or neglected as children. ACC = anterior cingulate cortex; PFC = prefrontal cortex. Research from Teicher et al. (2003).

Unmanageable or chronic stress fosters a reactive style of parenting that is narrowly focused on the immediate behavior and most negative aspects of the child. Parenting in this inflexible, hyperfocused way inevitably suppresses openness and positive feelings between parent and child, the very qualities in a parent–child relationship that help to sustain emotional bonds and build strong connections. Stressed-out parenting stresses the child and tends to promote a runaway feedback loop that ramps up mutual defensiveness between the two.

One of the hallmarks of stressed-out parenting is a tendency to overreact to a child’s nonverbal communication. Since our brains process nonverbal communication in the form of facial expressions, tones of voice, and gestures much faster than we consciously process the content of verbal communication, our reactions to each other’s nonverbal signals begin before we even really understand the words we are hearing. Under stress, this implicit rapid appraisal process is likely to be biased toward the negative aspects of the other person’s nonverbal expressions, easily triggering our defenses. The stressed-out parent, primed for detecting negativity in the child, reacts instantly to the child’s eye movements or subtle changes in tone of voice.

When a stressed-out parent keeps reacting to a child’s nonverbal “displays” of negative feelings, the parent–child interaction can get hijacked by mutual defensiveness. Reacting to each other’s “nonverbals” blocks the interaction from becoming more open and from going deeper into a sharing of inner experiences. And, since nonverbal communication is largely automatic, taking a child’s nonverbal expressions “personally” leads to misconstruing the child’s real intentions while pushing the parent’s “hot buttons.” Quickly triggered into defensiveness, the parent goes no further in trying to understand the child; in turn, the child starts to give up on getting the parent to listen or understand. This is a recipe for blocked care.

Another feature of parenting under stress is the strong tendency to be judgmental, both toward the child and toward oneself. Under stress, the brain makes rapid appraisals and judgments about what is going on between parent and child. These rapid assessments, in turn, produce simplistic cognitions, black-and-white thoughts about child and self. This one-dimensional way of carving up experience is adaptive for survival-based living. Parents under too much stress feel like they are fighting for survival and, sadly, they experience their children as the threat to their well-being.

The stressed-out brain, needing to keep things simple, has no time for ambiguity, complexity, or uncertainty. Survival is all about rapid assessment and quick action, requiring the reduction of complexity and the narrowing of options. This is a job for the amygdala and the lower limbic system, not for the hippocampus, with its need to compare and contrast, or for those higher, uniquely human parts of the prefrontal cortex that would only gum up the works with subtlety and complexity.

Because parenting is such an emotional and visceral process, parents have a strong tendency to take their children’s reactions to them personally, both the positive and the negative reactions. In brain terms, taking things personally is related to the activation of that lower stream in our brains, our limbic system, which is so tightly connected to our hearts and the rest of our bodies. When we react to anything in life that moves us strongly, this system is turned on, and when this system is on, we experience what is happening as highly personal, as happening to us, as being about us. This is why it is often difficult for us to deal with signs of rejection or invalidation when we are interacting with another person. Our first appraisal in these situations comes from our limbic system, not our higher, more objective and reflective regions of the brain. We can easily get captured in this “egocentric,” personalizing part of our brain’s reaction, especially if we are interacting with someone whose reactions to us really, really matter. For us as parents, the reactions we get from our children matter big time and are very likely to stir up our limbic systems, for better and for worse.

Recent studies using brain imaging show that the experience of feeling rejected activates the same pattern in the brain as feeling physical pain. In other words, emotional pain and physical pain are processed similarly in the brain (Ochsner et al., 2008). One of the key regions in the brain where social rejection registers is the anterior cingulate cortex, specifically the upper or dorsal region of the anterior cingulate cortex. This is also a key part of the brain involved in the suppression of painful feelings, both physical and emotional, and includes the dissociative process in which the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex is shut down, helping to create a scenario in which we feel no pain even as we are otherwise experiencing something that is “painful.” This is the way a young child can turn off the emotional pain caused by a parent’s hurtful, insensitive parenting. In this way, a child, and later a parent, can truly say, “I don’t care.”

Blocked care is likely to affect the parent’s brain by activating this social rejection system centering around the activation of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, the part of the brain that helps to detect conflicts or errors between an intended or anticipated result of parents’ attempts to care for children and children’s responses to their parents. In other words, when parents approach children anticipating positive reactions and instead the children react nonverbally (and, perhaps, verbally) in a way that parents perceive as negative, the brains of these parents may activate this social rejection system. Parents might then respond to this emotionally painful experience much like they would to physical pain: by drawing away and becoming protective of themselves. Being rejected by one’s child, even if the perception of rejection is a false alarm, is literally painful.

The activation of the social rejection system inevitably creates a visceral feeling that children’s reactions are personal, much as if they had literally hit parents or done something to cause physical pain. This “gut reaction” registers in the insula, that part of the brain that receives input from the visceral parts of the body, including the heart, lungs, and stomach region. As discussed earlier in relation to parental empathy, the insula and the anterior cingulate cortex are strongly connected, so whenever the insula is activated by our visceral systems, whether positively or negatively, the effects register in the anterior cingulate cortex, giving rise to gut feelings. If parents get immersed in this initial gut reaction to their children’s reactions, feelings of rejection are likely to become stronger and to affect the way the parents feel and think about those children.

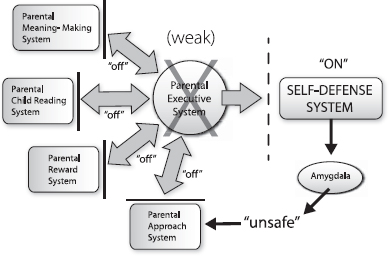

Indeed, activation of the social rejection brain circuitry is likely to affect all of the basic parenting systems—approach, reward, child reading, and meaning making. In the throes of feeling rejected, all of these systems would be, at least temporarily, suppressed, basically going offline while the parent’s self-defense system is online. In particular, the Parental Approach System and the Parental Reward System—the two brain systems that keep parents near their children and engaged in parenting—would be inhibited. Meanwhile, the Parental Child-Reading System—parents’ system for attuning to their children’s minds—would be highly constrained by their own defensive states of mind. This defensiveness would cause parents to perceive their children as being in a rejecting or ungrateful state of mind when this perception may be inaccurate or only a superficial reading of what the children are really experiencing. The meaning that parents construct while captured by this defensive reaction is likely to be negative and to further reinforce the immediately painful feelings of rejection. This meaning construction could be along the lines of “I’m a bad parent,” “You’re a bad kid,” “This is pointless—I give up,” etc. The risk that parents will experience social rejection when their children do not respond to their caregiving behaviors points to the importance of reciprocity in the parent–child relationship. In short, and as common sense tell us, it is much easier for parents to engage in ongoing caregiving behaviors when children respond in kind with warm, joyful engagement.

The key now is what happens with the Parental Executive System. Do the parents have the capacity to engage this system and start to regulate this “felt rejection” in a more productive way that can help them regain equilibrium and repair the connection with their children? If they are able to activate the Parental Executive System and regulate this powerful negative reaction, then they will be able to step back from taking their children’s reactions personally and reappraise the situation—to take a “second look” at what is going on, to reflect upon their children’s behavior and their own reactions to it. This is essentially a mindful response in contrast to a more automatic, reflexive, personalized response.

The Parental Executive System involves the top-down frontolimbic circuitry we described in Chapter 1, those “vertical” connections that could enable a parent to turn on the self-regulating system at the same time that the feeling of rejection is kicking in. Failure to engage the Parental Executive System at this point will mean that parents’ initial feelings of rejection, along with the automatic meaning that comes with it (“You don’t love me,” “You’re ungrateful,” etc.) will rule their brains and cause them to go into unregulated defensive responses. Blocked care is the result when the parental defense system is activated repeatedly, without the self-regulating help of the Parental Executive System. Figure 3.2 provides an illustration of this undesirable process.

Failure of the Parental Executive System to regulate unparental reactions suppresses all parenting systems.

Since blocked care involves the suppression of caring feelings, not permanent impairment of the potential for caring about a child, we see blocked care as a treatable condition. To us, this is the value of understanding the parental brain and how stress can suppress the caregiving process, making it seem to parents, and even to therapists, that the parents are simply uncaring and unempathic, when, in reality, their caring potential might very well be “awakened” or restored with sensitive, brain-based intervention. So next we turn to a discussion of understanding and assisting parents who have developed some type of blocked care.