36

THE VIRTUES OF COOPERATION

Cooperation and partnership are the only route that offers any hope of a better future for all humanity.

—KOFI ANNAN1

As Joël Candau, of the Department of Anthropology and Sociology at the University of Nice, points out: “Ours is the only species where one observes cooperation that is strong, regular, diverse, risky, extensive, and which involve punishments, often costly, between individuals who share no familial ties.”2 Mutual aid, reciprocal gifts, sharing, exchanges, collaboration, alliances, associations, and participation are all forms of the cooperation found throughout human society. Cooperation is not only the creative force that drives evolution—we have already seen that evolution needs cooperation to be capable of constructing increasingly complex levels of organization—but it also lies at the heart of the human species’ unprecedented accomplishments. It allows society to accomplish tasks that one person would not be able to accomplish by himself. When the great inventor Thomas Edison was asked why he had twenty-one assistants, he replied: “If I could solve all the problems myself, I would.”

Cooperation can seem paradoxical. As far as selfishness is concerned, the most attractive strategy is that of the “free rider” who benefits from the efforts of others to achieve his aims while expending the minimum of effort. Yet plenty of research shows that it is preferable—for oneself as well as for others—to trust one another and to cooperate rather than acting as a lone ranger. Although human beings have a certain tendency toward the “closed” cooperation linked to tribal instinct, they are also gifted with a unique aptitude for “open” cooperation, which goes well beyond an individual’s kin or social group.3

“As such,” Candau goes on, “human cooperation constitutes just as great a challenge to the most orthodox theory of evolution, underpinned as it is by the notion that competition between individuals who are concerned with their own reproduction alone, as it does to traditional economic theory founded on the existence of “selfish” agents devoted exclusively to the maximization of their own interests. Here we see an anthropological fact which demands explanations.”4

THE ADVANTAGES OF COOPERATION

One beautiful morning in the fall, I met with my friend Paul Ekman, one of the preeminent psychologists of our time, who has dedicated his life to the study of emotions. We first met in India in 2000, at a Mind & Life Institute conference organized around the Dalai Lama on the theme of destructive emotions, and we have been working together ever since.5

We had planned to spend a day together discussing the issue of altruism. As a result of his many meetings and conversations with the Dalai Lama, Paul too has become convinced that we must do all that is humanly possible to usher in a more altruistic, united and cooperative society, that is to say, a “global compassion.”6

He began by telling me how, in small communities and villages, the more the inhabitants cooperate, the more prosperous they become and the greater the chances their children have of survival. Among the tribes of New Guinea, where Paul worked in the 1960s, everyone has to muck in together, from preparing meals to assisting with childbirth or defending against predators. In these villages, no one wants to work with those who are prone to pick fights, and if somebody attempts to exploit another, his reputation will not go unscathed, leaving him with little chance of survival in the community. In a village, you can’t get away with exploiting others for long and you can’t run away from a bad reputation either. This is why over the course of time our genetic development has directed us toward cooperation. Furthermore, there is an inherent satisfaction in working together to achieve a common goal. As a result of natural diversity, there will always be people who are fundamentally selfish, but they only represent a margin of society. Unfortunately, as we saw in the chapter on institutionalized selfishness, they can, in certain circumstances, succeed in forming highly powerful oligarchies.

In a small community, if someone suffers, the others immediately feel concern and tend to help that person. Ephraïm Grenadou, a French farmer at the start of the twentieth century, recalls: “When we raised the alarm by ringing the village clock, if there was a fire or something, everybody would come very, very quickly. They would run from the fields, from their houses, from all over. Within a few minutes the village square would be heaving with people.”7 In our modern society, the media present us with more suffering in a single day than we would ever be able to alleviate in our whole life, a unique situation in the history of humankind. This is why, according to Paul Ekman: “If we are to bring about change that results in an increase in altruism, it must be selective, focused on specific goals, and linked to actions which have impacts and which form part of a social movement.”8

To what extent can cooperation and benevolence extend beyond our innermost circles? Nothing is set in stone: our education and cultural environment are at least as important as our genetic inheritance. The environment of the first five years of our lives has a particularly major influence on our motivations and emotions, which then go on to act as a filter for our perception of other people’s emotions. According to Paul Ekman, talking in evolutionary terms, appropriate emotions (i.e., emotions that have been adapted to a given situation and which are expressed constructively) favor cooperation. In other words, without cooperation, we cannot survive.

Human beings, by virtue of their language, their capacity for empathy, and their vast range of emotions, are gifted with a profound sociability that is rarely taken into account by public policy and is neglected by most economists. If we continue regarding ourselves as individuals driven chiefly by self-interest, greed and antisocial motives, we may keep in place systems based on reward and punishment, thus perpetuating a distorted and wretched version of the kind of humanity we aspire to. On the individual level, competition poisons emotional and social links.

In strongly competitive societies, individuals do not trust one another, they worry about their safety, and they constantly seek to promote their own interests and social status without much concern for others. On the other hand, in cooperative societies, individuals trust one another and are prepared to devote time and resources to others. This sets in motion a virtuous cycle of solidarity and reciprocity that nurtures harmonious relationships.

If cooperation benefits everybody, how do we promote it? For Joël Candau, choosing an “open” cooperation, which transcends social groups, is above all a moral choice, which necessarily means that we overcome the doubt inherent in the challenges faced by all members of society: must cooperation be confined to the members of a community or rather opened up to other groups? What balance can be struck between cooperation and competition? What happens to those who take advantage of a cooperative system in order to promote their interests alone?9

COOPERATION WITHIN A COMPANY, AND COMPETITION BETWEEN COMPANIES

According to Richard Layard, professor at the London School of Economics, cooperation is an indispensable contributing factor to prosperity within a company. For some time we have seen the idea gain traction that it is desirable to promote ruthless competition between the employees of the same company—or, in the case of education, the students in a class—since everyone’s performance would improve as a result. In reality, this competition is harmful, since it damages human relationships and working conditions. When all is said and done, as the economist Jeffrey Carpenter has shown, it is counter-productive and decreases the company’s prosperity.10

Teamwork is particularly undermined by individual incentives and bonus schemes. On the other hand, rewarding the performance of the team as a whole encourages cooperation and improves results.11 Managers and heads of business must therefore try to instill trust, solidarity and cooperation.

According to Layard, competition is only healthy and useful between companies. Placing companies in open competition stimulates innovation and research into ways of improving services and products. It also leads to a reduction in prices, to the benefit of everyone. The opposite occurs in heavily bureaucratic, centralized, state-owned economies, which more often than not result in stagnation and inefficiency.12

As we will see below, for cooperation to be more efficient than competition, a number of factors must come together, including the frequent practice of reciprocal services and the mutual appreciation of the services given. In traditional economic analysis, if cooperation is most efficient, then cooperative firms should be the ones that survive best in the long term.

THE COOPERATIVE MOVEMENT

As the historian Joel Mokyr observes, a company’s success lies less in having exceptional, multi-talented employees, and more in the fruitful cooperation between people with a good reason to trust each other.13 According to the International Cooperative Alliance, an NGO which represents cooperatives from across the world, a cooperative is “an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprise.” There is evidence to show that employees who have part-ownership of the business, and have their own say on the distribution of income, are more satisfied with their working conditions, enjoy better physical and mental health, and even have a lower mortality rate.14

As such, cooperatives like mutual funds and NGOs fall under the so-called social or caring economy. According to the ICA (International Year of Cooperatives, 2012), more than 1 billion people worldwide are members of cooperatives.15

MUTUAL TRUST SOLVES THE PROBLEM OF THE COMMONS

In an article that appeared in 1968 in the journal Science, one that would go on to be cited widely, Garrett Hardin discussed the “tragedy of the commons.”16 Taking the example of a rural village in England where each farmer can graze his sheep on a piece of land that does not belong to anybody, he put forward the hypothesis that, in such a situation, it is in the interest of each farmer to graze the maximum number of animals on an area which is available to everyone but where the resources are limited. This inevitably leads to overexploitation and, ultimately, land degradation. In the end, he thought, everyone loses out.

Hardin presented this as an inevitable outcome, without really basing his conclusions on solid historical data. Since his article was published, the “tragedy of the commons” has been a hot topic of discussion among economists. Hardin also cited the example of ocean exploitation, which threatened—one by one—to push various species of fish and marine mammals to the verge of extinction. On this point, his 1968 article was prophetic, since today 90% of large fish stocks have been destroyed.

On the other hand, in the case of the example cited by Hardin—the practice of using “common land” for grazing, which was standard for a long time in many European countries and is still carried out in some parts of the world, historical research has shown him to be mistaken. First, it is false to state that the land did not belong to anybody: it was unofficially the property of the community, which was well aware of its value. The members of this community had established a balanced system for regulating the use of commons that generally worked satisfactorily. As the historian Susan Buck Cox notes: “Perhaps what existed in fact was not ‘a tragedy of the commons’ but rather a triumph: that for hundreds of years—and perhaps thousands—… land was managed successfully by communities.”17

The ecologist Ian Angus18 agrees wholeheartedly, noting that Friedrich Engels had described the existence of this custom in pre-capitalist Germany. Communities which shared the use of land in this way were called “marks”:

“The use of arable and meadowlands was under the supervision and direction of the community.… The nature of this use was determined by the members of the community as a whole.… At fixed times and, if necessary, more frequently, they met in the open air to discuss the affairs of the mark and to sit in judgment upon breaches of regulations and disputes concerning the mark.”19

In the end this system succumbed to the Industrial Revolution and land reform, which granted supremacy to private property, big landowners, monoculture, and industrial farming. Land privatization has often had an adverse effect on prosperity. It has, for example, allowed landowners with an appetite for quick profit to destroy forests. Similarly it is big landowners, and not small communities, who have overexploited the land and caused soil erosion and depletion, excessive use of fertilizers and pesticides, and of monocultures.

Like many others, Hardin assumed that human nature was selfish and that society was made up exclusively of individuals who were indifferent to the consequences of their actions on society. In fact, his article has often been used to endorse land privatization. This was apparent, for example, in Canada, in 2007, when the conservative government proposed the privatization of the indigenous population’s land, with the so-called aim of facilitating their “development.”

A more realistic vision was put forward by Elinor Ostrom, the first woman to receive the Nobel Prize in economics, who spent most of her scientific career investigating this very issue. Her work Governing the Commons20 teems with examples of populations forming constructive agreements based on cooperative strategies. Indeed farmers, fishers, and other local communities the world over have created their own institutions and regulations aimed at preserving their common resources, ensuring that they last in the good years as well as the bad.

In Spain, in regions where water is scarce, the irrigation system used in the huertas has worked efficiently for more than five centuries, maybe as many as ten.21 The users of these irrigation networks meet regularly in order to modify their community management regulations, nominate officers, and resolve any occasional conflicts. Here cooperation works perfectly well and, in the Valencia region, for example, the illegal water withdrawal rate lies at a mere 0.008%. In Murcia, the water tribunal even goes by the name of the “Council of Wise Men.”22

In Ethiopia, Devesh Rustagi and his colleagues have studied the exploitation of communal forestry reserves by 49 groups in the Bale region in the province of Oromia. They noticed that the groups who managed their forestry resources the best were those with the most cooperative members. The putting in place of sanctions and the implementation of patrols to prevent stealing were essential to the success of this cooperative system.23

Ostrom has shown that the effective running of such communities depends on a number of criteria. First, the groups must have clearly defined borders. If they are too big, the members do not know each other and cooperation becomes a challenge for them. There must also be rules which govern the use of collective goods, but which can be modified according to any given circumstances to respond to specific local needs. Members must not only respect these rules, but also have in place a series of measures for cases of conflict and be willing to accept the fact that settling disputes can be costly. Ostrom’s work does not claim to prove that people are altruistic, but that they are able to devise institutions, based on reciprocity, which give them incentives to achieve socially desirable outcomes.24

Praising Ostrom’s work, French academic Hervé Le Crosnier drew the following conclusion: “Fundamentally, his message is that people who day in, day out face the need to guarantee the sustainability of the common resources which underpin their lives have a great deal more imagination and creativity than economists and theorists are willing to give them credit for.”25 The Internet offers countless examples of benevolent work that is valuable to the common good. The operating system Linux, for example, is an open source, non-commercial system whose codes are available to everyone, meaning it can be improved by programmers the world over.

COOPERATION AND “ALTRUISTIC PUNISHMENT”

In order for cooperation to prevail in society, it is essential to be able to identify and neutralize those people who profit from the good will of others, thus usurping the primary goal of cooperation. In a small community where everyone knows each other, free riders are swiftly detected and banished. On the other hand, when it is easier for them to go unnoticed, such as in towns or cities, it is crucial to promote cooperation by means of education and the transformation of social norms and by putting in place institutions that keep a check upon these free riders.

In April 2010, a meeting entitled “Is altruism compatible with modern economic systems?” was organized in Zurich under the auspices of the Mind & Life Institute and the Department of Economics at the University of Zurich (UZH).26 Eminent psychologists, cognitive science specialists, and social entrepreneurs gathered around the Dalai Lama. While there I had the chance to talk to Ernst Fehr, a very highly regarded Swiss economist, who challenged the paradigm that individuals have no consideration for anything beyond their own interests. His studies have shown that, to the contrary, the majority of people are inclined to trust others, to cooperate, and to behave altruistically. He concluded that it was unrealistic and counter-productive to develop economic theories based on the principle of universal selfishness.27

Ernst Fehr and his colleagues have on multiple occasions placed groups of people in situations where mutual trust plays a central role. For example, they asked them to take part in an economic game, with real losses or earnings at stake.

Typically the experiment would play out as follows. Ten people are given 20 euros. They can either keep the sum for themselves or put it toward a shared project. When one person has invested his 20 euros in the project, the researcher doubles his stake to 40 euros. Once the ten participants have decided on their strategy, the total amount invested in the project is distributed evenly between the members of the group.

It is clear that if everyone cooperates, everyone profits. Essentially, the 200 euros invested by the group, increased by the other 200 euros from the researchers, pays out 40 euros to each participant, or double their investment. This ideal outcome presupposes that each member of the group trusts the other or cares for the other. Indeed, all that is required for every member to benefit is for just over half the group to cooperate.

On the other hand, if mistrust prevails and nine people keep their 20 euros and just one invests his money in the shared project, when this meager sum is divided among everybody, the nine participants who refused to cooperate end up with 22 euros (their original 20 euros plus the 2 euros yielded from the sum shared out from the one person who invested in the project), while the single cooperator is left with a mere 2 euros (since his 20 euro investment has been shared out among all ten people), representing a loss of 18 euros. Traditional economic theory has it that, in a society of selfish people who are mistrustful of everyone else, cooperation is in no one’s interests.

Yet Ernst Fehr’s team observed in the course of multiple experiments repeated many times over that, contrary to received wisdom, 60% to 70% of people trust each other from the outset and collaborate spontaneously.

Across any population, however, there is always a certain portion of individuals who prefer not to cooperate (around 30%). What trend is observed here? Second time around, the cooperators, having noted that there were some bad players in the group, nevertheless carry on cooperating. As the game is repeated, however, they grow weary of those who are exploiting the trust seen elsewhere in the group to turn a profit without taking any risks. By the tenth round, cooperation, that is conditional to some form of fair reciprocity, breaks down and becomes practically nonexistent.

As such, the majority’s trust and goodwill erodes when a minority abuses the system for its own profit, harming the community as a whole. This is unfortunately what happens in an economic system that grants total freedom to unscrupulous speculators. It is also the consequence of wholesale deregulation of financial systems. The problem therefore is not that people are unwilling to collaborate and that altruism has no place in economics, but that profiteers prevent the majority’s readiness to cooperate from asserting itself. In other words, the selfish derail the system. This would not happen if our cultures were more oriented toward “caring” economics.

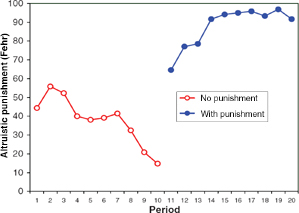

Can we prevent the breakdown of cooperation? Ernst Fehr had the idea of continuing the experiment by introducing a new parameter: the possibility of punishing the bad collaborators. Every participant could therefore make an anonymous payment of 1 euro so that a fine of 3 euros would be imposed on the profiteers by the researcher. This is what Ernst Fehr refers to as “altruistic punishment,” since it is costly to the person who imposes it and does not bring him an immediate return.28 Why should somebody act in this way? It seems absurd from the point of view of one’s personal interests, but the experiment shows that most people have a strong sense of fairness and are willing to spend a certain amount to ensure that justice is respected.

The impact of this new measure was spectacular. The cooperation rate skyrocketed and leveled off at almost 100%. It is important to note that this new protocol took place with the same participants as beforehand. The lone rangers, who had never contributed to the group’s profits, started to cooperate and invested all of their money in the communal project.

In the first phase of the test, the selfish members had undermined the group dynamic. In the second, the altruists succeeded not in turning the selfish members into altruists—unfortunately a utopian ideal—but rather in creating a system where the selfish had a vested interest in behaving as if they were altruists.

In the end, everyone benefits from this, to the extent that if after a few rounds of the game the group is given the option of repealing the altruistic punishment, all of the participants express their desire to keep it in place, including the 30% of free riders, who realized that the group was functioning much better and that they themselves were reaping the rewards. Altruistic punishment is a very ancient method by which primitive societies managed to sustain efficient cooperative systems for tens of thousands of years.29 In fact, even if everyone was selfish, the players could still use punishment or establish rules that make cooperation desirable to promote their individualistic self-interest. But societies can do better since wise altruists can establish rules and institutions that encourage a caring economy to flourish, while keeping in check the hard-core free riders with proper safeguards.30

A graph showing the decline in cooperation under the influence of the profiteers, and the spectacular increase in cooperation following the introduction of altruistic punishment

Research shows that in the absence of rules a breakdown in cooperation occurs no matter the culture. However, the effects of altruistic punishment differ considerably from one culture to the next. In some cultures, the majority of people do not appreciate their upholders of justice, and take revenge by punishing them on their own. Unable to identify individual cooperators, they decide to punish them randomly to make them realize that they would do better not to get mixed up in other people’s business. An antisocial punishment therefore replaces the altruistic punishment.

This trend is strong in cultures with little sense of civic duty, where the state is inefficient, there is scant respect for justice, and people do not trust their corrupt law enforcement agencies. In these countries, fraud is not just accepted but considered a means of survival. One can measure the strength of a culture’s sense of civic duty by assessing, for example, the percentage of the population that considers it acceptable to dodge fares on public transport.

Benedikt Hermann and his colleagues studied the behavior of the inhabitants of sixteen towns across the world.31 They observed that antisocial punishments—which seek to undermine this sense of civic duty rather than encourage it—were practically nonexistent in Scandinavian countries, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and other countries where there is an emphasis on cooperation and community values. By contrast, they are found in abundance in countries with a weak sense of civic duty and where cooperation is restricted to between close relations or friends. In these circumstances, antisocial punishment is predominant. This can be observed, for example, in Greece, Pakistan and Somalia, three countries that score very poorly in the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) published each year by Transparency International.32

It is also apparent that societies with established altruistic standards flourish more and manage the problem of the commons better. If Danish people can leave an unsupervised baby to take some air in its stroller outside a restaurant at lunchtime without fearing it might be kidnapped—something that would be considered madness in Mexico or New York—it is because they have a certain value system programmed into them.33 If the inhabitants of Taipei and Zurich automatically pay their bus or tram fare even in the absence of anyone to check whether they do so or not, it does not show that they are natural-born profiteers forced to conform to regulations through fear of being punished: they pay for their ticket voluntarily and are shocked if they see someone break the law. In countries where illegal practices are culturally accepted, profiteers always find ways of fulfilling their goals, regardless of the number of inspectors.

It is therefore important to bring together several strategies: putting in place appropriate institutions which allow altruists to cooperate without obstruction, to channel selfish behavior into prosocial behavior by establishing sensible and fair regulations, improving norms through education and helping the caring potential of human beings to be fully expressed and become the predominant attitude in our cultures.

BETTER THAN PUNISHMENT: REWARD AND APPRECIATION

The evolutionists Martin Nowak and Drew Fudenberg, from Harvard University, have noted how, in real life, interactions between individuals are generally not anonymous and rarely occur in isolation. When people know who has cooperated, who has cheated, and who has punished them, the dynamic of these interactions changes. What’s more, people worry about their reputations and do not want to run the risk of being ostracized by their peers for behaving antisocially.34

Studying the behavior of very young children shows that they are capable of noticing how an individual cooperates with others, and deducing from that whether or not he will cooperate well with them. In fact, from the age of one, they prefer people who behave in a cooperative manner.35

In this context, Nowak and his colleagues wondered whether, in real life, rewarding good cooperators would be more efficient than punishing the bad ones. Punishments deemed “altruistic” by economists do not in truth say anything about their motivations. A punishment is genuinely altruistic if, say, a parent corrects his or her children to prevent them from picking up bad habits. Punishments can also be motivated by the feeling that it is important to maintain a sense of fairness in society. Often, however, they boil down to a form of vengeance. The neuroscientist Tania Singer showed that men are particularly willing to part with a certain amount of money solely for the pleasure of taking revenge after being wronged in a trust game.36 In circumstances where the persons involved can be identified, there is a strong risk that revenge will trigger a vicious cycle of reprisals in which everyone gets hurt.

In a series of experiments conducted by David Rand and other researchers under the direction of Nowak and Fudenberg, it emerged that over the course of repeat interactions in a trust game which allowed individual cooperators and free riders to be identified (thus altering the terms of Ernst Fehr’s experiment, where the participants were anonymous), the strategy which produced the best long-term results involved continuing to cooperate no matter what happened.37 In a group of two hundred students, those who saw the most significant success were the persistent cooperators. Those who engaged exclusively in vengeful behavior generally found themselves locked in a cycle of reprisals that made them crash to the bottom of the leader board.

Costly punishments are therefore just an effective stopgap, even if they are far more worthwhile than taking a laissez-faire approach. The best way of increasing the level of cooperation, however, is clearly to give favor and encouragement to positive interaction—fair exchanges, cooperation, and the strengthening of mutual trust. A system centered on rewards and encouragement that is linked to the safeguarding of rules and punishments which let one be protected against free riders does seem, therefore, the most apt way of promoting a fair and benevolent society. In a company, in particular, it is more constructive to create a pleasant working environment, to honor good and loyal service in various ways, and to redistribute a share of the profits to employees, than it is to penalize them if they grumble about carrying out their tasks. Once again we see that cooperation is more effective than punishment.

FAVORABLE CONDITIONS FOR COOPERATION

In his work Why We Cooperate, the psychologist Michael Tomasello explains that mankind’s cooperative actions are founded in the existence of a shared objective, the attainment of which requires participants to assume different roles coordinated by concerted attention.44 Collaborators must be receptive to others’ intentions and react to them in appropriate fashion. In addition to a shared objective, collaborative action requires a certain division of the workload and an understanding, guaranteed by good communication, of each individual’s role. Cooperation demands tolerance, trust and fairness.

It is also reinforced by social norms, which have varied enormously over the ages. The philosopher Elliott Sober and the evolutionist David Sloan Wilson have reviewed a large number of societies from across the world and observed that in the vast majority of them, behaviors deemed acceptable are defined by social norms. The important thing about these norms is that it does not cost much to uphold them, whereas punishments can, by contrast, be very costly to those on the receiving end—exclusion from the community, for example.45 Thankfully we live in a time where social norms tend more toward respect for life, human rights, equality between men and women, solidarity, nonviolence, and fair justice systems.

Martin Nowak, for his part, describes five favorable factors for cooperation. The first is the regular practice of reciprocal services, as is the case, for example, with farmers who help each other at harvest-time, or villagers who all join in to build a neighbor’s house. The second factor is the importance of reputation in communities: those who cooperate willingly are appreciated by everyone, while poor cooperators are badly regarded. The third factor involves population structure and social networks, which either facilitate or thwart the formation of cooperating communities. The fourth factor is the influence of family ties, with greater cooperation seen among related individuals. The fifth and final one is linked to the fact that natural selection operates on multiple levels: in certain circumstances, selection occurs solely on the individual level, while elsewhere it influences the fortunes of a group of individuals taken as a whole. In this second case, a group of cooperators can also have more success than a group of bad cooperators who are constantly in competition with one another.46

For generations, human beings have developed a web of reciprocity and cooperation in villages, towns, states, and, nowadays, across the whole world. Through the connectivity of global networks, information and knowledge can spread around the entire planet in a matter of seconds. If a stimulating idea, an innovative product, or a solution to a vitally important issue is circulated in this way, it can be used to benefit the whole world. There exist, therefore, countless methods that are conducive to developing cooperation. Looking to the future, we need to cooperate more than ever, and to do so on a global scale.