1

Know Your Knits

Other than the singular common characteristic of all knits—that they stretch—the variety of knits available today is staggering. Some knits stretch very little, while others stretch more than you can imagine. From smooth and lustrous to loopy and bulky, the range of fibers, textures, and looks is alluring. Your sewing will be enhanced once you learn more about the types of knits manufactured today.

Characteristics of Knits

Although the variety of knit fabrics is tremendous, they all share, to some degree, the same characteristics. Knits don’t ravel, they generally don’t wrinkle, they do tend to shrink, and they all stretch, some a little and some a lot. These characteristics make knit fabrics fun (and usually quick and easy) to sew and very comfortable to wear.

Ravel Resistance

Due to the interlocking construction of knits, they do not ravel. This means that it is not necessary to “finish” the raw edges either inside or outside the garment, which simplifies construction, saves time, and minimizes bulk along the seams and hems.

Many knits look good with simple, smooth, and “unfinished” cut edges. However, novelty knits, such as sweater knits, have ragged edges that are not as attractive, so edge finishing might be necessary on these specialty knits.

Wrinkle Resistance

Most knits are wrinkle resistant, but their particular fiber content and construction technique does determine the degree of wrinkling. Viscose rayon and bamboo knits tend to wrinkle, sometimes badly, while polyester and nylon are nonwrinkling fibers. ITY (interlocking twist yarns) and textural constructions prevent wrinkling, as well.

Shrinkage

Some knits shrink dramatically, others very little. Most knits tend to shrink more than woven fabrics. See here for a way to determine how much your particular fabric will shrink.

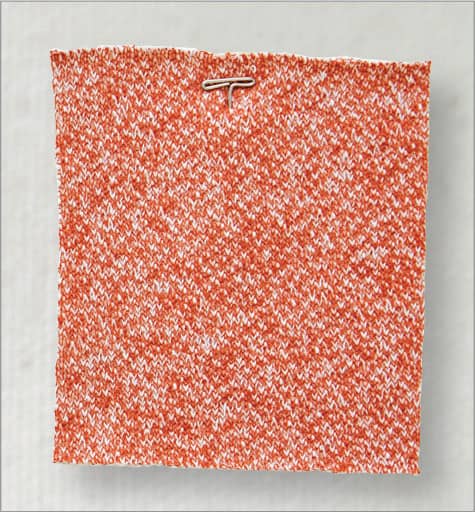

A bamboo knit (foreground) and an ITY knit.

Stretch and Recovery

Knits stretch in varying degrees from almost no stretch to 100% beyond their original (prestretched) size, depending on the construction technique, fiber types, addition of elastic fibers (such as spandex), and surface finishes. Recovery, or the way the fabric springs back to its original size after stretching, is important, too. Garments made from knits with good recovery tend not to sag, “bag-out,” or lose their shape. Some knits are very stable, with little stretch, and can be sewn just like a woven fabric.

Fibers

Knits are manufactured in many fibers that are generally divided into three categories. Each of the fibers can be knitted in almost all weaves and weights.

• Natural fibers such as cotton, wool, silk, linen, and rayon are commonly used. These are extremely comfortable because they are soft, absorbent, and breathe well.

• Organic fibers such as bamboo, hemp, and soy have similar properties to natural fibers but are grown and manufactured using sustainable and eco-friendly methods.

• Synthetic or manmade fibers are easy to care for and hold their shape, but are not absorbent and, therefore, retain heat and may develop static electricity. These fibers include polyester, acetate, triacetate, nylon, and acrylic.

• Rayon: The Semisynthetic Fiber •

Rayon typically falls into the natural fiber category, although it is really a hybrid. Rayon is a generic term for manmade fibers composed of regenerated cellulose derived from trees, cotton, and woody plants.

The first generation of rayon fabric was manufactured in the 1890s under the name “artificial silk” and became commercially available in 1910. The process of producing rayon is called viscose. When referring to fabric, the two terms, rayon and viscose, are interchangeable.

Modal is the second generation of rayon and was developed in 1964 creating rayon that has higher wet strength and is softer than the original. It dyes just like cotton and is long wearing.

Lyocell, the third generation of rayons, was developed in 1990. Tencel® is the trade name. This fiber has excellent cooling properties, is hypoallergenic, and prevents the growth of bacteria, which cause odors.

Rayon and modal are manufactured using toxic solvents that are released into the air. Tencel is manufactured in a more environmentally friendly manner, using solvents that are almost completely recovered.

You may see any of these terms when purchasing rayon fabrics today.

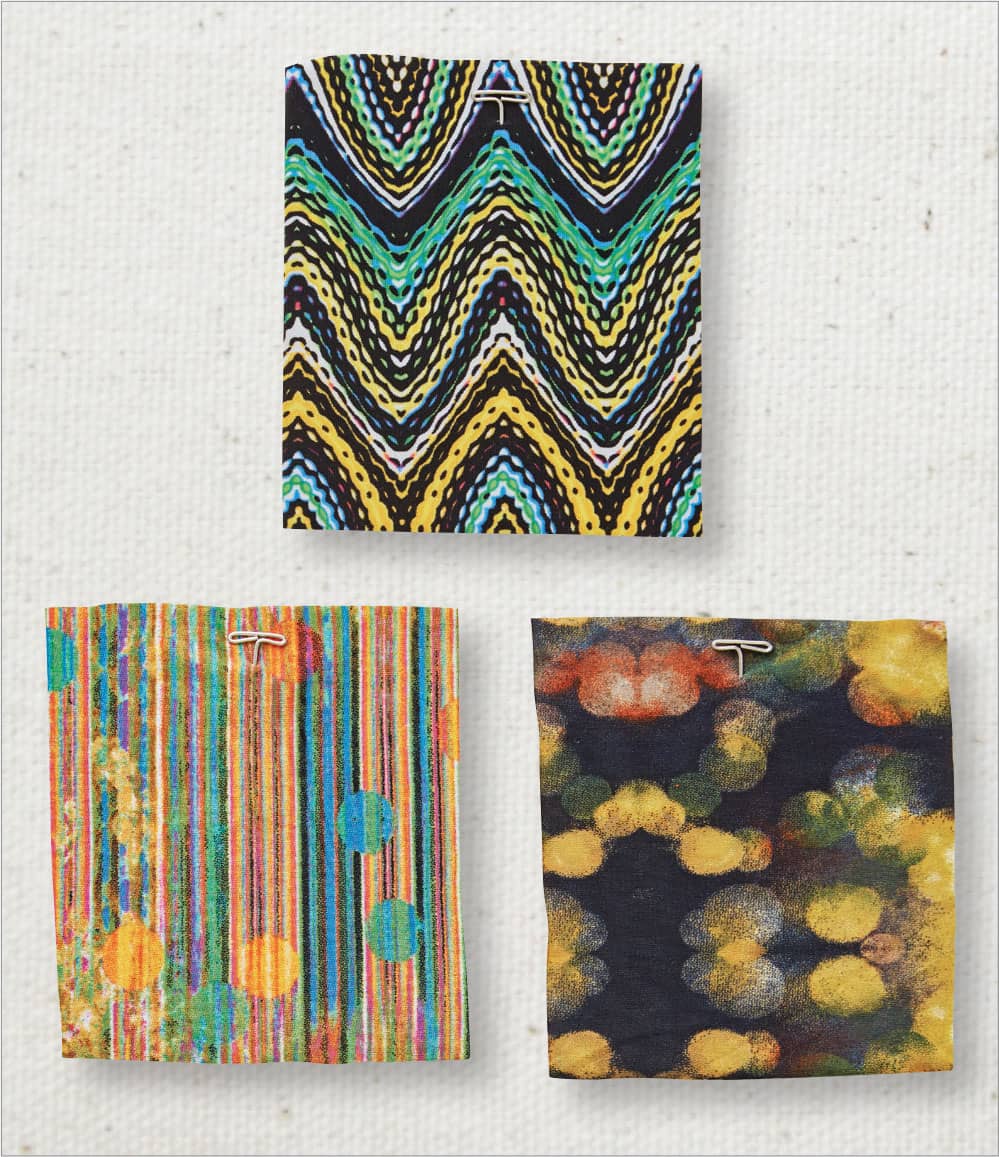

Knit fabics in a variety of fibers. Top row, from left to right: cotton, cotton nylon, rayon. Center row: wool, bamboo, linen. Bottom row: polyester, nylon cotton, acrylic.

Fabrics

Understanding the basic construction of the different knits and their characteristics will help you determine which type of knit works best for any and every pattern choice.

Knits are manufactured in two general groups, weft and warp knits. Weft knits are made from a single yarn looped horizontally to form a row, with each row building on the previous one, just as in hand knitting. Warp knits are made with numerous parallel yarns that are looped vertically at the same time. Most machine-made knits are weft knits. All of these knits are made from four basic stitches, plain, purl, rib, and warp.

• The Four Basic Knit Stitches •

Plain Stitch (Knit Stitch)

The plain stitch is a machine or hand stitch that produces a series of lengthwise ribs on the face and horizontal loops on the back of the fabric.

Rib Stitch

The rib stich is a machine or hand stitch characterized by the alternation of prominent ribs on both sides of the fabric.

Purl Stitch

The purl stitch is a machine or hand stitch that produces horizontal loops across both sides of the fabric.

Warp Stitch

The warp stitch is a machine-only stitch formed by looping in a lengthwise direction, forming a zigzag pattern.

Weft Knits

Weft knits are produced using only one yarn with plain, purl, or rib stitches. They include

• Jersey

• Interlock

• Ribbing

• Sweater knits

• Double knits

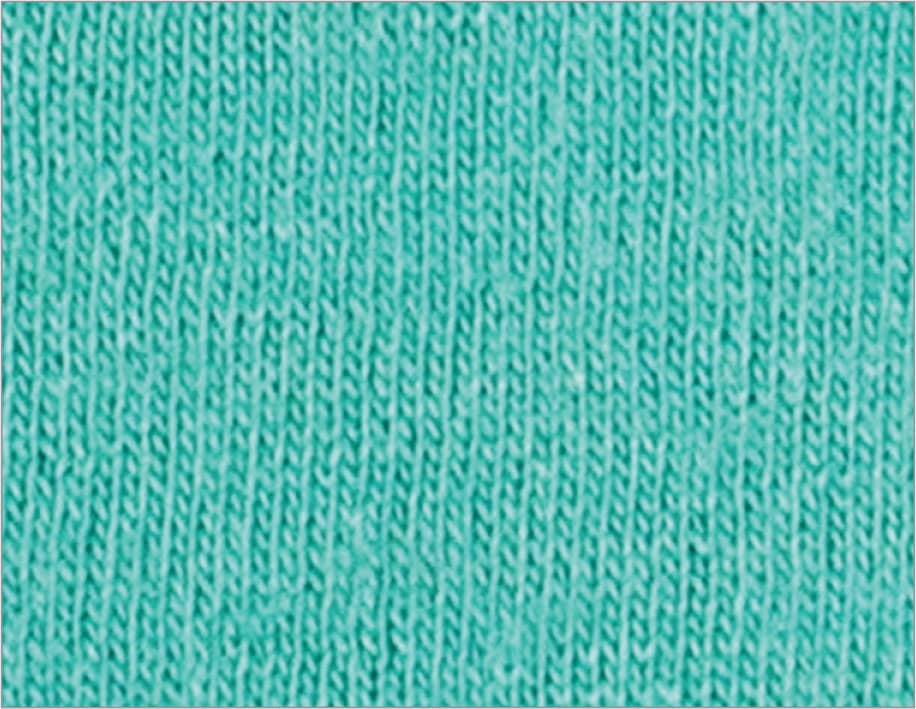

Jersey

Jersey, a single knit, is the most basic machine-made knit. It has lengthwise ribs (knit stitch) on the right side and horizontal rows (purl stitch) on the reverse.

Jersey is available in just about any variety of fibers and fabric weights, from stable cotton to tissue-sheer silk to super-slinky rayon fabrics, and many include the addition of 2–10% spandex fibers. Jersey’s identifying feature is that it curls to the right side when stretched on the cross grain. This makes it somewhat difficult to handle and sew, but it can also be an advantage when you want fashionable raw edges.

Properties:

• Soft and drapeable

• Tends to run easily

• Can be napped, printed, and embroidered

• Ripping out stitches may leave holes and marks

• Substantial wrinkling in certain fibers

• Gathers into fluid folds

Garment Types:

• Tops, tanks, and T-shirts

• Scarves

• Dresses

• Skirts

• Soft jackets and coats

• Pants and leggings

• TIP •

When sewing with jersey, especially tissue and lightweight variations, select pattern styles that are relatively simple without a lot of details such as zippers, plackets, and structured collars.

ITY (Interlock Twist Yarn)

ITY knits are relatively new and are composed of interlocking twist yarns. A twist is added to the yarn to add elasticity.

Properties:

• Very soft, inside and out

• Good drape

• Excellent stretch and recovery

• Wrinkle resistant

• Produced primarily in polyester, often with added spandex

Garment Types:

• Top, tanks, and T-shirts

• Dresses

• Activewear

• Loungewear

Stretch Velour and Velvet

Available in a variety of fibers, stretch velours and velvets have a plush nap on the right side and lengthwise ribs on the reverse.

Properties:

• Plush face has a nap, requiring one-way nap layout

• Fabric should be cut out in a single layer with plush side down

• Fabric layers shift during sewing

• Can be bulky

• Requires special care when pressing

• Nap can flatten, reflecting the light differently and changing color

Garment Types:

• Loungewear, robes

• Tops, T-shirts

• Dresses

• Pants

• Sportswear

• Childrenswear

Stretch Terry and French Terry

Stretch terry is distinguished by loops on both sides, like bath towels. French terry has loops on only one side.

Properties:

• Loops can be different sizes, flat, thin, or chunky

• Requires with-nap pattern layout

• Edges shed so edge finishing is required

• Can be bulky

• Edges can curl badly

• Presser foot toes can get caught in the loops

• Tends to snag easily

Garment Types:

• Swim cover-ups

• Loungewear, robes

• Sweatshirts, hoodies, sweatpants

• Casual jackets

• TIP •

The “wrong” or loop side of French terry can be used as the right side for textural contrasts within the same garment.

Fleece and Sweatshirt Fleece

Fleece, distinguished by a fuzzy nap on both sides and commonly known as polar fleece, is used in athletic wear for warmth, windproof qualities, and moisture-wicking. Sweatshirt fleece has a smooth side and a fuzzy, napped side.

Properties:

• Cozy hand

• Bulky

• Attracts lint

• Edges curl

• Fuzzy nap side can pill

• Requires with-nap pattern layout

Garment Types:

• Sleepwear

• Tops

• Jackets

• Dresses

• Athletic wear, sweatpants, sweatshirts

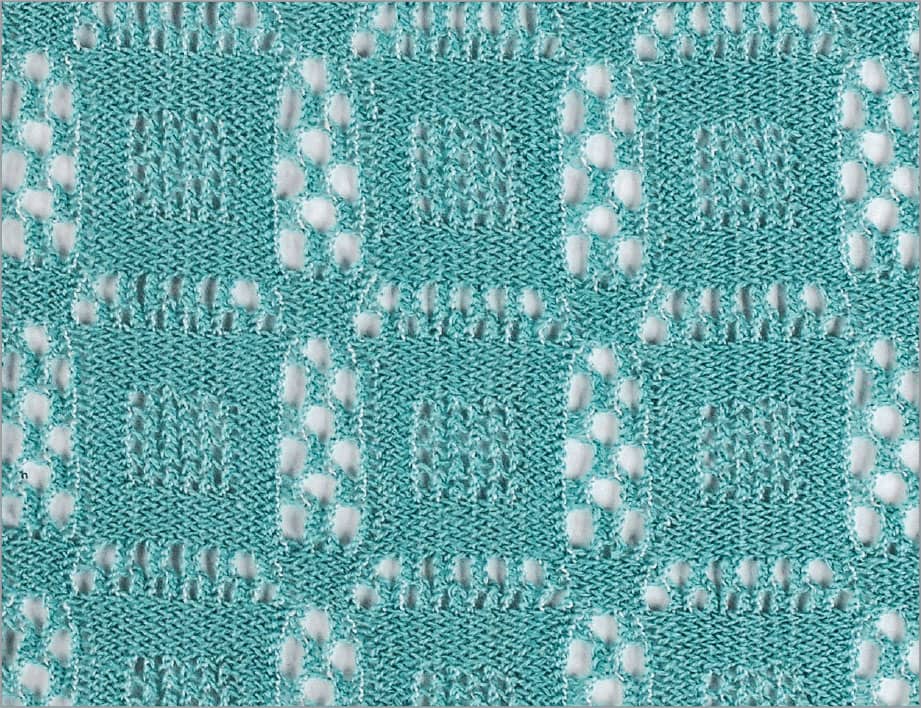

Sweater Knits

Sweater knits feature a wide range of looks, they can be solid or textured with openwork or even intricate stitch patterns, but what sets them apart is that they all resemble hand knitting. Stitch patterns include jacquards, cables, ripples, ribs, and tucks.

Properties:

• Infinite varieties of textures and patterns

• Can distort when stitching and wearing

• Can be bulky

• Can be so open in the weave they are difficult to sew

• May unravel at edges, requiring stabilizing and special sewing techniques

• Requires with-nap pattern layout

Garment Types:

• Scarves

• Jackets

• Tops

• Dresses

Double Knits

Double knits are constructed on a circular machine by interlocking loops with two sets of needles. Both sides look the same. They can be soft or crisp and have very little stretch.

Ponte and Ponte di Roma are two common terms for the new double knits. They are sturdy, often blended with spandex, and are used by top designers to make smooth, sculptural silhouettes.

Properties:

• Stable, firm

• Hold shape well

• Easy to sew

• Edges do not curl

• Good recovery when blended with spandex

Garment Types:

• Jackets

• Tops

• Dresses

• Pants

Interlock

Unlike jersey, interlock fabrics are thicker, with fine ribs on the front and back; both sides look identical. Interlock is a cousin to a double knit but is generally lighter weight and has a bit more drape. It does not have as much recovery as jersey, but it is easier to sew.

Properties:

• Cut edges do not curl

• Firm hand

• Retains shape

• Use with-nap pattern layout

• Puckers and skipped stitches may occur

Garment Types:

• Top, tanks, T-shirts

• Jackets

Rib Knits

Rib knits have prominent ribs on both sides, which gives them the ability to expand and contract more than other knits. They are available in 38–45" (96.5–114 cm)-wide yardage, in a tube, or as narrow rib knit trims. Commonly used for areas that need greater stretch and recovery, such as trims, cuffs, and bands.

Properties:

• Super stretch

• Can distort during stitching

Garment Types:

• Fitted T-shirts, tanks (beefeater shirts)

• Legwarmers

• Hats

• Slinky Knits •

A variation of a rib knit, this super stretchy knit drapes extremely well, never wrinkles, and is the perfect travel fabric. Acetate and Lycra blends perform exceptionally well.

Warp Knits

Warp knits utilize many yarns and feature only one stitch—the warp stitch. Fabric types include tricot, Milanese, and Raschel.

• Milanese and Raschel Knits •

Milanese and Raschel knits are warp knits, but the home sewer rarely sees these terms labeling over-the-counter fabrics. Milanese is smoother and stronger than tricot and is used in more expensive lingerie. Raschel knits are more diverse in their weaves and include lace, tulle, and nettings, as well as many novelty weaves.

Tricot

This light- to medium-weight fabric is opaque and strong enough to resist runs. Common fibers used are nylon, acetate, and triacetate.

Properties:

• Easy to sew

• Smooth and conforms to the body

• Snags easily

Garment Types:

• Slips, camisoles

• Sleepwear

• Robes

• Linings

Buying Fabric

In a perfect world, you could shop at your favorite local fabric store and touch every piece of fabric to know which ones feel best for all your projects. If you are lucky enough to be able to buy locally, then shopping with your hands is the most reliable way to find the perfect fabrics.

You will be able to test the stretch and recovery of the fabric, how well it drapes, how soft or crisp it feels, and compare colors in natural light. You will know the degree of rolling at the edges and be able to decide if you want to tackle a knit that rolls excessively. You might even be able to tell if a fabric will pill by folding it with the right sides together and rubbing the layers together, or check to see if it is already pilling on the bolt.

If you can’t shop locally, or you are looking for a specific fabric, online buying is the next best option. In this case, though, you need to know the properties and behavior of the different fibers and the technical terms for knit types so you know what you are looking for and can understand the usually brief descriptions. Many of the independent fabric stores and online resources will send you samples upon request.

How Much to Buy

Most knits are between 58" and 63" (1.5 and 1.6 m) wide; the most common width is 60" (1.5 m). Some, but very few, are 45" (1.1 m) wide and these are mostly of Japanese origin. If the fabric is available only in a tube, you can cut along one fold and use it as full-width yardage.

Check the width of the fabric. Compare the width of the fabric to the yardage requirement listed on the pattern envelope and buy accordingly. Or, if you haven’t already selected a pattern, but have fallen in love with a fabric, you can estimate how much fabric you’ll need using this chart. It is always a good idea to buy at least 1/4 yard (22.5 cm) extra to allow for shrinkage and have scraps for technique testing. Here are some guidelines.

Estimated Yardage by Garment/Fit |

|

T-shirt: Short sleeve |

11/4 yd (1.1 m) |

T-shirt: Long sleeve |

13/4 yd (1.6 m) |

Top/Blouse |

21/2 to 3 yd (2.3 to 2.7 m) |

Jacket/Coat |

3 to 4 yd (2.7 to 3.7 m) |

Dress |

2 to 3 yd (1.8 to 2.7 m) |

Skirt: Slim |

1 yd (.9 m) |

Skirt: Full |

2 yd (1.8 m) |

Pants: Slim |

15/8 yd (1.5 m) |

Pants: Full |

23/4 yd (2.5 m) |