5

Basic Construction Techniques

Constructing a knit garment is similar to making a woven garment, with some processes being exactly the same and others quite different. A major difference is in the handling the fabric. Since the fabric does not ravel and edges may not need to be finished, there is less work. Working with knits requires a more delicate touch in order to get refined results.

Order of Construction

Constructing a garment in a particular order allows you to access various areas of the garments more easily and finishes the details perfectly.

Below is the standard order of construction for tops and pants.

Tops

1. Hem prep

2. Darts/tucks/zipper (if applicable)

3. Shoulder seams

4. Neck/collar finishing

5. Side seams

6. Sleeves/armhole finishing

7. Complete hems

Pants

1. Hem prep

2. Darts/tucks/zipper (if applicable)

3. Side seams

4. Inner leg seams

5. Crotch seam

6. Waist finish

7. Complete hem

Neck Finishes

There are many ways to finish a neck opening on a knit top; however, a fabric binding is the most common. Neck bindings are perhaps the most visible components of knit garments, so they need to be handled with care.

Binding

Binding, the popular ready-to-wear technique for finishing a neck opening, is an easy method for the home sewer to duplicate.

Cutting the Binding

If a binding pattern piece is included with your pattern, then use it. If there is no pattern available, then use the following formula to make your own binding.

Measure the finished circumference of the neck opening on the seamline of the paper pattern pieces; do not include shoulder and other seam allowances.

To calculate the length of the binding, determine 7/8ths of the original circumference (divide the circumference by 8 and multiply that number by 7 or multiply by .875). The binding should be shorter than the original circumference.

To calculate the width of the binding, decide how wide you want the visible amount of the binding to be. Multiply that number by 2 and add the width of two seam allowances.

For example:

1/2" (1.25 cm) visible width × 2 = 1" (2.5 cm) + 5/8" seam allowance (3.2 cm) × 2 = 21/4" (5.7 cm) cutting width

Every knit differs in its stretch factor, so this calculation is only a starting point. If a knit is extremely stretchy, the binding should probably be cut shorter. If the knit is fairly stable, it might need to be longer. You will need to apply the binding and then try on the garment and see how easily it slips over your head, and evaluate how it fits and shapes the garment neckline. You might need to remove the binding, cut a new and shorter binding, and try again.

Preparing the Binding

1. Fold the binding in half lengthwise with wrong sides together and press. If the edges curl and prevent you from pressing the binding flat, use a narrow strip of fusible web tape to fuse the layers together (A).

2. With right sides together, stitch the narrow ends of the binding together to form a circle (B).

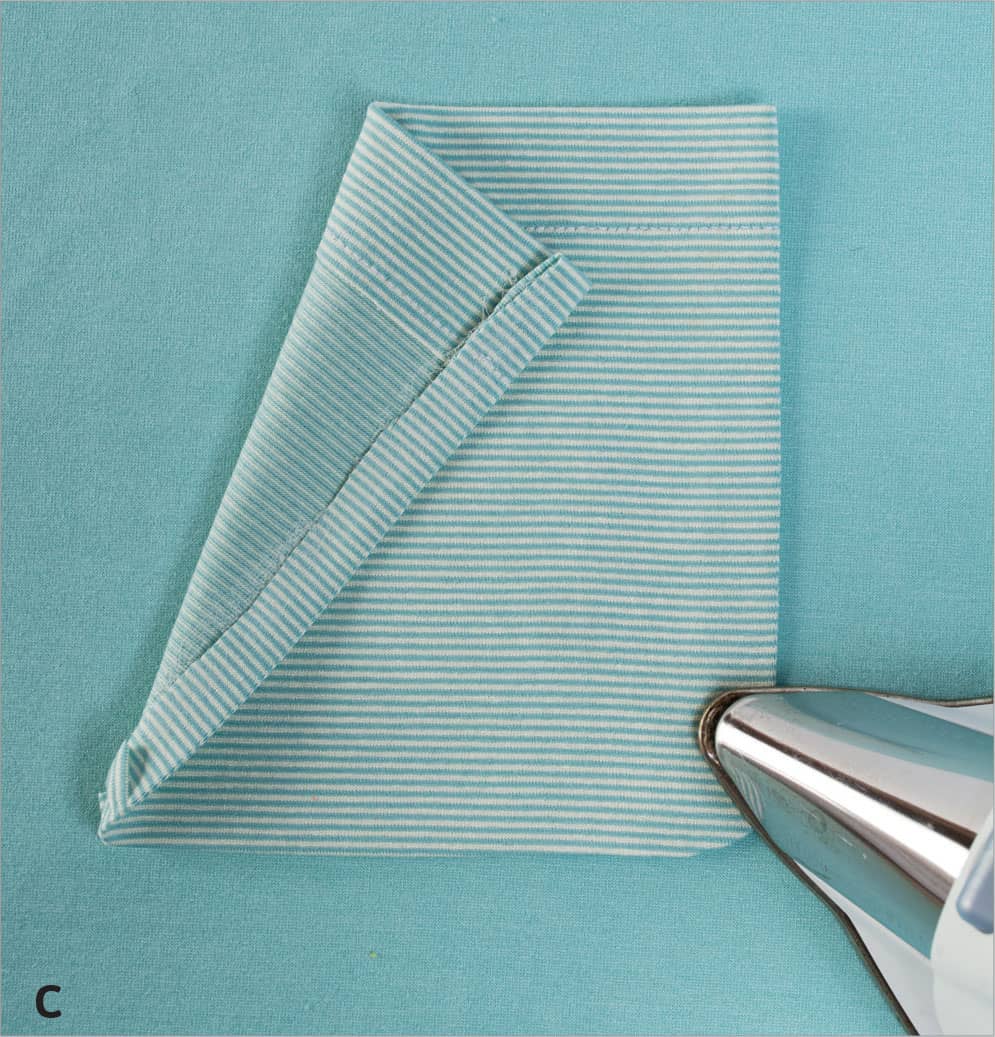

3. In order to apply the binding evenly around the neck opening, divide both the binding and the neck opening into quarters. Start by folding the binding in half with the seam at one end. Clip into the seam allowance (but not through the seamline) at the opposite end fold (C).

4. Refold the binding, stacking the seam on top of the clip mark to find the quarter markings. Clip into the seam allowance at these two new end folds (D).

5. To quarter-mark the neck opening, pinch the shoulder seams together and clip into the seam allowance of the front and back at the folds (E).

6. Then, pinch the front and back clips together and clip into the seam allowance to mark the end folds. These clips will not necessarily be located at the shoulder seams (F).

Applying the Binding

1. With right sides together and raw edges aligned, match the clip marks on the binding with the clip marks on neck opening, with the binding seam at the center back of the garment. Pin at each clip mark (A).

2. Starting at the center back, line up the left side of the presser foot with the outer folded edge of the binding. Move the needle position to the right the distance of the finished binding. With your right hand, hold the next quarter-marked pin and stretch the binding to match the neck opening, keeping all raw edges together. Stitch from pin to pin using your left hand to control the alignment of the binding to the neck edge (B).

3. You can either trim the seam allowance close to the stitching and leave the edges raw, or use a three-thread overlock stitch to serge the raw edges together (C).

4. Finger-press the seam allowance toward the inside of the garment, which turns and exposes the front side of the binding on the right side of the garment. Position the binding under the sewing machine presser foot so the needle is positioned just above the seamline. Then, move the needle to the left position and stitch next to the seam, catching the seam allowance on the wrong side (D).

5. Once the binding is completely sewn, place the neck opening over a tailor’s ham. Apply steam to the binding and hand press the binding to help form a smooth and flat curved shape (E). Allow it to dry before removing it from the ham.

Turned and Stitched

When a binding is too thick or too sporty, a simple turn and stitched finishing method works well, especially when sewing stretch lace and other novelty textures or if you want a very smooth neck edge.

Set the differential feed so the stitches draw up the opening slightly (refer to your owner’s manual). Serge the raw edge of the neck opening using a three-thread overlock stitch. Turn the serged edge to the wrong side and topstitch it in place.

Both sides of a finished turned and stitched neck treatment.

V-neck Binding

Applying a binding to a V-shaped neckline is the same as applying any binding, the only difference is sewing the V shape.

1. Reinforce the V-shaped area of the neckline by stitching inside the seam allowance, pivoting at the V. Start and stop stitching a few inches (cm) before and after the V. Clip into the V, but not through the stitching (A).

2. It is difficult to pin the binding to the entire neckline. Starting at the center back and with right sides together, pin the binding to the neckline up to the center of the V, with the last pin in the clipped point of the V. Begin stitching at the center back and continue stitching up to the last pin at center of the V. Leave the needle in the fabric, raise the presser foot and pivot the work, allowing the clipped V to open up. The rest of the binding can now be pinned to the other side of the garment in order to complete the seam. Trim the seam allowance close to the stitching (B).

3. Without turning the binding to the inside of the garment, fold both the garment and the binding along the center front with the right sides together. Stitch only through the binding, along the centerfold (C). This helps the binding take the shape of the neckline. Clip the binding seam allowance to the V. Follow steps 4–5 in Applying the Binding shown here to finish the neckline.

Cowl Neck

Attaching a cowl is nothing more than sewing a wide binding to a neckline. Use the same pattern piece as for a standard binding, only make it substantially wider or any width that you desire. A cowl can be doubled like a binding or a single layer and hemmed on one edge. Either way, it is applied in the same manner as the standard binding (see here).

Attaching Sleeves

The stretch inherent in knit fabrics makes it easy to ease shaped sleeves into an armhole opening or to sew them flat to armhole edge before the side seams are stitched.

Flat Method

Sometimes, sleeves are attached flat (before the underarm seam is stitched) to garments that are still flat (before the side seams are stitched). This method is usually done on T-shirts and casual tops. Shoulder seams are stitched first, and then the top of the sleeve is stitched to the armhole with right sides together. In this situation, the sleeve and garment edges align evenly, so it is a matter of simply matching the notches and markings and sewing the sleeves to the garment using the seam of your choice.

In the Round

This method is used when the sleeve cap is more curved and needs to be eased into the armhole opening. These sleeves are typically found in more fitted garments such as blouses, dresses, and jackets. The side seams and the sleeve seams are sewn first, so the insertion is literally “in the round,” a tubular sleeve inserted into an armhole opening.

1. Prepare the sleeves as you would for a woven fabric. Sew a line of basting stitches just inside the seamline along the sleeve cap and between the notches; leave long thread tails at each end of the stitching. Gently pull the bobbin thread to ease the fabric and add shape to the sleeve cap. Place the sleeve over the tapered end of a tailor’s ham and steam the fullness of the seam allowance, gently pressing the stitching (A).

2. With right sides together, pin the sleeve into the armhole, matching seams and other match points. Starting at the top of the sleeve, roll the seam allowance over your fingers and insert a pin perpendicular to the basting. Moving down one side of the sleeve between the top, the notches, and the underarm seam, roll sections over your fingers to ease the sleeve into the armhole opening; continue to pin regularly. When one side is done, start at the top and repeat on the other side (B).

3. Once the sleeve is pinned in place, stitch just inside the basting stitches with the sleeve side facing up. Leave the seam unfinished or serge with the three-thread stitch (C). Repeat for the other sleeve.

4. Place the sleeve over the tailor’s ham or use a press mitt to lightly hand press the sleeve from the outside of the garment. Avoid pressing the sleeve flat after you have worked so hard to build shape into it.

Elasticized Waists

Most skirts and pants with elasticized waists feature elastic in a fabric or ribbon casing or an exposed elastic inside the garment.

Types of Elastic

There are five general categories of elastic.

Braided Elastic

Braided elastic is identified by parallel ribs, that run the length of the elastic. It is available in several widths, it narrows when stretched, and snags during stitching. It is most often used inside neckline casings and sleeve hems.

Knit Elastic

Knit elastics are soft and don’t narrow when stretched. You can sew through these elastics so they are typically used inside casings or exposed in pajamas, athletic wear, and pants and skirts made in light- to mid-weight fabrics.

Woven Elastic

Woven elastic, called “no-roll” elastic is strong and characterized by vertical ribs. These elastics are used in casings in mid- to heavyweight fabrics for pants and skirts.

Lingerie Elastic

Lingerie elastic features a scalloped or picot decorative edge. It is generally used on bras, undies, and lingerie, but it's fun to use in children’s clothing, too.

Elastic Ribbon

Elastic ribbon looks like grosgrain ribbon with a groove down the center, which helps the ribbon fold over an edge, forming a binding. It is available in many solid colors as well as fun patterns and is used for sleek neck bindings, waistbands, and decorative edgings on sportswear, athletic wear, and childrenswear.

Stitching Elastic Ends

There are three ways of connecting the ends of a length of elastic to form a circle.

• Braided, knit, lingerie, and ribbon elastics can be seamed just like fabric bindings since they are so lightweight (A).

• Woven elastic needs to be overlapped and stitched (B).

• Or they should be butted and covered with a piece of fabric or ribbon (C).

Elastic in a Casing

Creating an elastic casing in knits fabric is just as easy as in woven fabrics.

There are two types of elastic casings. One is simply the top edge of the garment pressed to the inside and the other is a separate waistband. Whichever way you wish to create the casing, simply leave an opening in the stitching that forms the casing (often in the center back) through which to insert the elastic.

Attach a bodkin or large safety pin to one end of the elastic and feed the elastic through the casing. Then use one of the methods above to secure the ends of the elastic together. Complete the stitching to close the opening in the casing.

Exposed Elastic

Many knit garments, from athletic wear to high fashion skirts and pants, feature exposed elastic as a waistline finish.

1. Measure the finished waist circumference on the pattern rather than the garment to get an accurate number. Cut the elastic to this length.

2. Sew the ends of the elastic together with 1/2" (1.3 cm) seam allowance; press the seam open. This makes the length of the elastic 1" (2.5 cm) smaller than the circumference of the garment.

3. Fold the elastic in half and mark the center front directly opposite the seam.

4. On the right side of the garment, chalk-mark a line 3/8" (9 mm) from the raw edge of the waistline. Pin the wrong side of the elastic to the right side of the waistline with the elastic along the chalk-marked line. Match the center back and center front (A).

5. Set your sewing machine to a 2 mm (.08 inch) long by 4 mm (.16 inch) wide zigzag stitch or a stretch stitch. Stitch the elastic to the garment, stretching the elastic slightly to fit the waistline (B).

6. Turn the elastic to the inside of the garment, forming a facing. On the right side of the garment, stitch vertically through all the layers (fabric and elastic) along all vertical seams (center front/back, side seams, darts, etc.) to secure the elastic in place (C).

Buttonholes

There are a few tricks for sewing buttonholes in knits so they lie flat without puckers and they don’t stretch out.

It is important to make a lot of practice buttonholes, recording the various stitch adjustments until you make the perfect buttonhole. Always practice on the same number of layers as in the garment and in the same direction as the final buttonhole. Buttonholes tend to look better if they are sewn parallel to the rib of the knit.

How to Make a Buttonhole

1. Stabilize the area by placing one or two layers of tricot interfacing between the fabric layers (A).

2. Place lightweight paper under the work and next to the throat plate when stitching the buttonholes. Pattern tissue paper works well (B).

3. Increase the stitch length, especially when sewing lightweight knits. You do not want a really densely sewn buttonhole. If you have a preprogrammed buttonhole for sewing knits on your machine, use it. Stitch the buttonhole (C).

4. Cut the buttonhole open with a special buttonhole-cutting tool. This two-piece tool consists of a cutting blade and a small block of wood. The beveled blade on the cutter avoids cutting the threads (D).

5. You can also use a seam ripper, but proceed with caution because it is easy to inadvertently cut the threads. If you do use a seam ripper, place pins at each end to act as fences to prevent you from cutting into the thread ends (E).

Invisible Zippers

Sometimes a zipper can be eliminated in a knit garment because of the stretch factor. But when a zipper is needed, an invisible zipper is the best option.

To install an invisible zipper, you will need a special zipper foot specifically designed for invisible zipper installations, as well as a presser foot that swings from side to side for securing the bottom of the zipper. Some machines do not come with this type of zipper foot, but you can purchase a generic sliding zipper foot that attaches to an adaptor for this purpose.

Do not sew the seam until after the zipper is installed.

1. Fuse 1" (2.5 cm)-wide strips of lightweight tricot interfacing to the wrong side of the opening, centered over the seamlines (A).

2. Chalk-mark the seam allowances on the right side of the garment and mark points 3/4" (1.9 cm) from the top edge of the garment.

3. On the right side of the garment, press strips of fusible web tape within the seam allowances and remove the paper covering (B).

4. Open the zipper and lightly press the coils of the zipper open, taking care not to melt the coils.

5. Finger press one half of the zipper along one seam allowance so the zipper stop aligns with the marking near the top edge and the coils align with the marked seam allowance. Fuse the zipper tape in place.

6. Install the invisible zipper foot. Starting at the top and on the right side of the garment opening, stitch the zipper tape in place as far as possible toward the end of the zipper (C).

7. Repeat for the other side of the zipper, checking to make sure the zipper is not twisted.

8. To finish sewing the bottom of the zipper, change to the presser foot that moves from side to side.

9. Move the foot out of the way of the needle. With right sides of the fabric together, insert the needle into the previous stitches about 1/2" (1.3 cm) from the end of the stitching (steps 7 and 8). Use the hand wheel to walk the machine for a few stitches so that all stitches are on top of one another (D).

10. Once the stitches have bypassed the bottom of the zipper, change to a standard presser foot and finish stitching the seam (E).

Ribbing

Although ribbing is used at necklines, it’s more commonly used for cuffs and hem bands. When using ribbing at a neckline, use the same technique as described here for neck binding.

Making a Rib Cuff

Because ribbing stretches so much, cuffs need to be smaller than the garment opening.

1. Measure your wrist. Cut each cuff: 10% to 25% shorter (depending on the amount of stretch of the fabric) than the wrist measurement + the width of 2 seam allowances × 2 times the desired width + the width of 2 seam allowances.

2. Fold the cuff in half widthwise with the right sides together. Either sew or serge the edges together (A).

3. Fold the cuff in half lengthwise, with the raw edges aligned. Place a pin at the seam and another pin at the opposite fold. Repeat this process on the sleeve (or leg opening). Pin the cuff to the right side of the sleeve (or leg opening), matching all raw edges and pins (B).

4. Starting at one pin, begin sewing or serging, stretching the cuff between pins to match the sleeve (or leg opening). Stitch from pin to pin (C).

The inside of the finished cuff with a serged edge.

Garment with ribbed cuff, hem band, and neckline.

Pockets

Since knits don’t ravel, it is possible to remove the seam allowances and apply a patch pocket with raw edges showing. If you prefer a more finished look, turn the seam allowances to the wrong side.

Using a Pocket Template

Use a pocket template to help control the size of the pocket and prevent distortion.

1. To make a template, trace the finished size of the pocket pattern onto a piece of cardboard or a manila file folder (A), using a tracing wheel and tracing paper. Cut out the template with a rotary cutter.

2. Use the pocket pattern to cut the pocket from the fabric. Finish the top of the pocket according to the pattern instructions.

3. Place a piece of tissue paper on an ironing surface, with the pocket, wrong side facing up, on top of the paper. Position the template in the center of the pocket. Bring the paper and the pocket seam allowances up and over the edges of the template. Press through all the layers (B). This method keeps the edges smooth and symmetrical and avoids burning your fingers.

4. To prevent pockets from shifting when stitching them to the garment, press strips of fusible web tape on the wrong side of the pocket, remove the paper covering, and fuse the pocket in place before topstitching (C).

Darts

Darts are not always necessary in knit garments since the fabrics are so stretchy, but when darts are needed, it is important to sew them with care, especially in tissue and lightweight knits where there show-through is possible.

1. To sew darts accurately, chalk-mark the stitching lines of the dart. Begin stitching at the outside edge (no need to backstitch), sew along the stitching line and start to taper the stitching toward the fabric fold about 1/2" (1.3 cm) from the end point of the dart. End the stitching at the fold and leave thread tails (A).

2. To retain the shape formed by the dart, steam press the dart in one direction over a tailor’s ham. Apply hand pressure and avoid pressing with the iron beyond the stitching (B).

Darts can be more than just simple bust or hip darts for fitting the curves of a body. Sometimes they are strategic design lines that create shaping and architectural interest in non-traditional places such as darts that are left open at the ends for a softly pleated and draped effect, or long darts that begin at the hemline of a dress and continue to just below the bust, creating a bell-shape.

Embellishments

Hand stitching adds a hand-crafted look to a garment. Use three or four strands of cotton embroidery floss to appliqué an interesting motif along a raw-edge hemline. Use a simple running stitch, a blanket stitch or a traditional appliqué stitch to outline the edge of a complementary color of knit or mimic the motif in another place such as a sleeve edge.

Linings

The idea of lining a knit garment is somewhat counterintuitive, and most knit garments can stand on their own without underlinings and linings, but there are some garments in which a lining is a nice addition. Lining adds structure, conceals the inner construction of a garment, and adds longevity to a fine garment. Tailored dresses, slim-fitting skirts, and elegant jackets, often constructed in stable knits, benefit from the addition of a lining.

If you have selected a knit fabric for its color, texture, or overall character and stretch is not a factor in the fit and appearance, then use a traditional woven lining such as Bemberg rayon, silk crepe de Chine, or silk charmeuse. When lining is needed for some support or to make a sheer fabric more opaque, choose a lining that has stretch such as tricot. You can also use a woven lining as long as it is cut on the bias so it stretches enough to work with the knit fabric.