Main Topics

KEY IDEA

The Roth 401(k) and Roth 403(b) plan options offer high income participants an entrée to the world of tax-free wealth accumulation that was previously unavailable to them via traditional plans.

What Are Roth 401(k)s and Roth 403(b)s?

In Chapter 1, we touched on some of the basic differences between traditional and Roth 401(k)s and 403(b)s. The Roth 401(k) and Roth 403(b) combine the features of a traditional 401(k) or traditional 403(b) with a Roth IRA. Employees are permitted to deposit part or all of their own contribution, which is the amount deducted from their paychecks, as a contribution to a Roth account, meaning it will receive tax treatment similar to a Roth IRA. The laws governing retirement plan contributions, however, require that the employee always have the option to defer money into the traditional deductible account when the Roth account is offered as an option. No one is forced to use the Roth account if they prefer to take the tax deduction.

Unlike traditional

contributions to a 401(k)

or 403(b) plan, employee

contributions to a Roth

401(k)/403(b) account do

not receive a federal tax

deduction. But the growth

on these contributions will

not be subject to taxes

when money is withdrawn,

because the Roth account

grows tax-free.

Unlike traditional contributions to a 401(k) or 403(b) plan, employee contributions to a Roth 401(k)/403(b) account do not receive a federal tax deduction. But the growth on these contributions will not be subject to taxes when money is withdrawn, because the Roth account grows tax-free. In short, if you have two options for your retirement plan, one a traditional account and the other a Roth account, with the same amount of money in each, the Roth account will be of greater value since the income taxes imposed on withdrawals from the traditional 401(k) greatly reduce its overall value. By this, I do not mean to imply that the Roth retirement plans are better than the traditional plans for everyone, but they are for many. The choice is similar to deciding whether to make a Roth IRA contribution or a deductible contribution to a traditional IRA as discussed in Chapter 2.

These significant additions

to the retirement planning

landscape offer many

more individuals an

extraordinary opportunity

to expand, and, in many

cases, to begin saving

for retirement in the Roth

environment where their

investment grows tax-free.

Roth retirement plans were first offered in 2006, but under temporary rules. Many employers did not add the Roth feature to their existing plans because of the additional paperwork, plan amendments, reporting, and recordkeeping involved. More recently, the law has become permanent and more employers are now offering Roth 401(k) and 403(b) features. These significant additions to the retirement planning landscape offer many more individuals an extraordinary opportunity to expand, and, in many cases, to begin saving for retirement in the Roth environment where their investment grows tax-free. Coupled with the increased contribution limits for the traditional 401(k) and 403(b) plans, employees and even self-employed individuals will be able to establish and grow their retirement savings at a rate greater than ever before.

How Do Roth 401(k)/403(b) Accounts Differ from a Roth IRA?

One of the most significant advantages of the Roth 401(k)/403(b), and the one that distinguishes it from a Roth IRA, is that Roth 401(k) and Roth 403(b) plans are now available to a much larger group of people. Roth IRA contributions are only available to taxpayers who fall within certain Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) ranges. The 2015 income limit for Roth IRA contributions for married couples filing jointly is $193,000 and for single individuals and heads of household, less than $131,000. If your income exceeds these limits, you are not permitted to contribute to a Roth IRA. These restrictive MAGI limitations do not apply to Roth 401(k) or 403(b) plans, providing higher income individuals and couples with their first entrée into the tax-free Roth environment.

This increased accessibility is really big news. Roth IRAs have always appeared to be ideal savings vehicles for wealthier individuals, but up until January 1, 2006, or more recently if their employers just began offering the Roth 401(k) and 403(b) options, wealthier individuals had been precluded from establishing Roth accounts due to the income limits.

The longer the funds are

kept in the tax-free Roth

environment, the greater

the advantage to both the

Roth IRA owner and his

or her heirs.

In Chapter 2 we demonstrated how Roth IRAs can be of great advantage as part of the longterm retirement and estate plan, and these wealthier individuals are the folks who can generally afford to let money sit in a Roth account and gather tax-free growth. The longer the funds are kept in the tax-free Roth environment, the greater the advantage to both the Roth IRA owner and his or her heirs.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Roth 401(k)/403(b) Contributions

The Roth 401(k)/403(b) plan option offers advantages and disadvantages similar to those of Roth IRAs discussed in Chapter 2,but they are worth repeating and expanding upon here:

Advantages of the Roth Plans

1. By choosing the Roth, you pay the taxes up front on your contributions. While you might have taken the tax savings from your traditional plan contribution and invested the money in after-tax investments, over time, you will receive greater value from the tax-free growth.

2. If your tax bracket in retirement stays the same as it was when you contributed to the plan, you will be better off (assuming the Roth account grows, and possibly even if it goes down in value somewhat).

3. If your tax bracket in retirement is higher than when you contributed to the plan, you will be much better off. (Please note that we will look more closely at the effect of higher and lower tax brackets in retirement later).There are many reasons why you could move into a higher tax bracket after you retire. Here are a few examples:

a. The federal government could decide to raise tax rates.

b. You need to increase your income with taxable withdrawals from your traditional IRA plan, perhaps because you have medical expenses that were not covered by insurance.

c. You own or inherit income-producing property or investments that begin to give you taxable income.

d. You own annuities or have other lucrative pension plans that begin paying you income because of Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs).

e. The combination of your pension, Social Security, and RMDs are higher than your former taxable income from wages.

4. While you are alive, there are no RMDs from the Roth IRA accounts. Roth 401(k)s/403(b)s are subject to RMDs, but, as of this writing, these plans can easily be rolled into a Roth IRA upon your retirement. Traditional plans have RMDs beginning at age 70½ for retirees. The Roth IRA provides a much better long-term, tax-advantaged savings horizon, as shown in Chapter 2.

5. Your heirs will benefit from tax-free growth if the Roth is left in your estate. They can extend the tax-free growth over their lifetimes by taking only the required withdrawals. Whatever advantage you achieved with the Roth can be magnified by your heirs over their lifetimes.

6. The Roth provides greater value for the same number of dollars in retirement savings. This may lower federal estate and state inheritance taxes in an estate with the same after-tax spending power.

7. If you are in a low tax bracket now, or even if you have no taxable income (possibly because of credits and deductions), contributing to the Roth plan instead of the traditional plan will not cost you a significant amount now, but it will have enormous benefits later.

8. If you were previously unable to consider Roth IRAs because your income exceeded the income caps, you are now eligible to consider Roth accounts.

9. If you need to spend a large amount of your retirement savings all at once, withdrawals from a traditional plan would increase your marginal income tax rate. The Roth has a significant advantage in these high spending situations.Because Roth withdrawals are tax-free, they do not affect your marginal tax rate.

10. Having a pool of both traditional plan money (funded by the employer contributions and taxable upon withdrawal) and Roth plan money (funded by the employee and tax-free) to choose from, can give you an opportunity for effective tax planning in retirement. With both types of plans, the Roth portion can be used in high income years and the traditional plan can be used in lower income years when you are in a reduced tax bracket. These low tax brackets may occur during years after retirement, but before the RMDs from the employer’s contributions begin.

Disadvantages of the Roth Plans

1. Your paycheck contributions into the Roth 401(k)/403(b) are not tax deductible, as is a traditional 401(k)/403(b) contribution. You will get smaller net paychecks if you contribute the same amount to a Roth account, rather than a traditional account, because of increased federal income tax withholding. Losing the tax-deferred status means that by the time you file your tax return, you will have less cash in the bank, that is, in your after-tax investments. (Keep in mind, however, when compared to tax-deferred or tax-free retirement savings accounts, after-tax investments are the least efficient savings tool).

2. The retirement investments may go down in value. If the decline becomes large enough, it is possible that you would have been better off in a traditional tax-deferred plan, because, at the very least, you would have received a tax deduction on your contributions.

3. If Congress ever eliminates the income tax in favor of a sales tax or value-added tax, you will have already paid your income taxes. However, it seems unlikely that such a system would be adopted without grandfathering the rules for plans in place to prevent such inequities.

4. If your tax bracket in retirement drops, and you withdraw funds from your retirement assets before suficient tax-free growth, the taxes you save on your Roth 401(k) plan withdrawals are less than the taxes you would have saved using a traditional plan. This can be the case if you earn an unusually high amount of money from your employer in one year, maybe from earning a large bonus that puts you in a very high tax bracket, but ultimately you do not end up with such high income after retirement. If that were the case, a better approach might be to use the traditional account for deferrals in that year or other years where your income is unusually large. (Please note that later we will look more closely at the effect of lower tax brackets in retirement).

Availability of the Roth 401(k)/403(b)

Employers who now offer a 401(k) plan or a 403(b) plan may choose to expand their retirement plan options to include the Roth 401(k) or Roth 403(b), but they are not required to do so. Some companies were early adopters; others may take more time to incorporate the new plans into their offerings; still others may never offer them.

Employers who now offer a

401(k) plan or a 403(b) plan

may choose to expand their

retirement plan options to

include the Roth401(k) or

Roth 403(b), but they are

not required to do so.

Contribution Limits for Roth and Traditional 401(k)s/403(b)s

For 2015, the traditional and Roth 401(k)/403(b) employee contribution limits are $18,000 per year, or $24,000 if you are age 50 or older). Employer matching contributions don’t affect this limit.

In 2015, a 50-year-old employee cannot make a $24,000 contribution to a traditional 401(k) account and a $24,000 contribution to a Roth 401(k) account; the contributions to both accounts combined cannot exceed $24,000. The Roth 401(k)/403(b) contributions will be treated like a Roth IRA for tax purposes.

Perhaps an example would help.

Joe, a prudent 55-year-old employee, participates in his company’s 401(k) plan. He has dutifully contributed the maximum allowable contribution to his 401(k) plan since he started working. Until his employer adopted the new Roth 401(k) option, his expectation was to continue contributing the maximum into his 401(k) for 2015 and beyond.

Now Joe has a choice. In 2015, he can either continue making his regular deductible 401(k) contribution ($24,000); he could elect to make a $24,000 contribution to the new Roth 401(k); or he could split his $24,000 contribution between the regular 401(k) portion and the Roth 401(k) portion of the plan. His decision will not have an impact on his employer’s contribution—the employer’s matching contribution remains unchanged and goes into a traditional tax-deferred account.

With Joe’s $24,000 contribution, however, there is a fundamental difference in the way his traditional 401(k) is taxed and the way his new Roth 401(k) is taxed. With the traditional 401(k), Joe gets an income tax deduction for his contribution to the 401(k). After Joe retires, however, and takes a distribution from his traditional 401(k), he will have to pay income taxes on that distribution. If Joe contributes to the Roth 401(k), he will not get a tax deduction for making the contribution, but the money will grow income-tax free. When Joe takes a distribution from his Roth 401(k), he will not have to pay income taxes, provided other technical requirements are met. These other requirements are usually easy to meet, and include such things as waiting until age 59½ before making retirement account withdrawals and waiting at least five years from the time the account is opened before the first withdrawal.

Because Joe has some after-tax savings already and does not really need more income tax deductions, he is advised to contribute to the Roth 401(k). Assuming Joe takes my advice and switches his annual contributions to the Roth 401(k), he will have three components to his 401(k) plan at work. He will have the employer’s matching contributions in his traditional account, plus the interest, dividends and appreciations on those contributions, to the extent that he is vested in the plan. He will have his own (the employee’s) traditional portion of the plan, which consists of all of his contributions to date plus the interest, dividends, and appreciation on those contributions. Then, starting in 2015, he will have a Roth 401(k) portion for his Roth contributions.

If Joe is married filing a joint tax return and his 2015 adjusted gross income is less than $193,000, he may have already been making contributions to a Roth IRA outside of his employer’s retirement plan. In 2015, he would have been able to make the maximum Roth IRA contribution of $6,500 ($5,500 for people under age 50) to the plan. And remember that Joe can contribute the maximum ($24,000) to his Roth 401(k), plus the maximum ($6,500) to his Roth IRA, assuming that his income is below the exclusion limits. As long as Joe is working, the Roth 401(k) at work will remain separate from any Roth IRA he may have outside of his employer’s plan.

If his 2015 adjusted gross income was more than $193,000, he would not have been allowed to contribute to a Roth IRA (the income phase-out range is between $183,000 and $193,000). What is much different for Joe is that the amount of money he will be allowed to contribute into the income tax-free world of the Roth will see a dramatic increase, because there is no income limit for employees who want to contribute to a Roth 401(k) or 403(b) plan at work.

Choosing between the Roth and Traditional 401(k)/403(b)

The following analysis is equally important for individuals considering a Roth IRA conversion. I do not repeat this analysis in Chapter 7, but people who are considering a Roth IRA conversion, or interested in learning more about them, should read this material with the Roth conversion in mind.

Many clients come to us wondering whether they would be better off making contributions to a Roth account or to a traditional retirement account. If the choice is between using a Roth IRA versus a nondeductible traditional IRA, it is pretty easy to make the case for the Roth. However, because of the nature of the Roth’s advantages and disadvantages, which are contingent on your current and future income tax brackets, there is no one size fits all answer if the choice is between a traditional deductible IRA and a Roth. So I have formulated some different scenarios showing how the Roth accounts become advantageous for some people and a bad idea for others.

Assume that we have an employee named Gary who is 55 years old, and who is able to contribute $24,000 to his 401(k) plan for eleven years, until he retires at age 66. His employer offers a Roth account in their 401(k), and Gary wants to know if he should direct his contributions to the Roth or the traditional side of the plan. We ran the numbers using the following assumptions:

1. Gary earns a conservative rate of return of 6 percent annually on all of his accounts.

2. At age 70, Gary rolls the Roth 401(k) part of his plan over to a Roth IRA to avoid RMDs. (This is a very important step; we’ll cover more about it later).

3. Gary knows that he will save a significant amount in taxes if his contributions are made to the tax-deductible traditional account. Gary is more disciplined than most savers. He is willing to take all of the money that he saved on taxes and contribute it to an after-tax brokerage account environment.

4. In this scenario, Gary’s income tax rates are as follows:

a. 25 percent ordinary incremental tax rate during his working years.

b. 25 percent ordinary incremental tax rate during his retirement years.

c. Capital gains tax rates are 15 percent.

5. Gary’s RMDs from his traditional 401(k) plan begin at age 70. He pays ordinary income taxes on the distributions, and uses the rest of the money to pay his living expenses. The Roth account has tax-free spending withdrawals taken in the same amount.

6. The calculated income tax rate on all growth of the after-tax account averages 16.5 percent.

7. At the end of each year, we measure the spending power for each scenario. To measure the spending power of pre-tax traditional 401(k) plan balances, an allowance is made for income taxes. The tax rate of this allowance or liquidation rate is, initially, 25 percent, comparable to the ordinary tax rate.

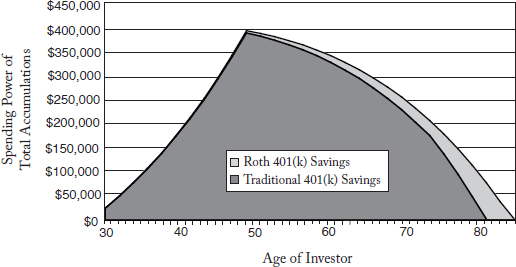

Now we are able to run the numbers and see the resulting spending power of remaining assets as shown in Figure 3.1 on the following page.

Figure 3.1 shows that there is an increasing advantage from investing in the Roth 401(k) instead of the traditional 401(k) plan. Although it’s dificult to see, the advantage begins in the first year. At Gary’s retirement age of 66, the advantage has grown to $6,101, or 1.45 percent. By age 75, after RMDs have begun, the advantage is 4.11 percent; by age 85, it is 9.68 percent; and by age 95, it is a 22.00 percent advantage resulting in an additional $162,680 for the Roth owner.

Figure 3.1

Roth 401(k) Savings vs. Traditional 401(k) Savings RMD is Spent Annually

For an individual person whose circumstances match the assumptions above, the cumulative advantage over the 40-year projection period should provide the incentive to use the Roth rather than the traditional 401(k). And if a rate of return greater than six percent is assumed, the advantage to the Roth owner increases significantly.

Under current rules, if Gary should pass away and leave his Roth account to his surviving spouse, she will not have to take RMDs from the account over her lifetime. If he leaves the Roth account to someone other than his spouse, perhaps a child, they can still extend the period of the tax-free growth by limiting distributions to the RMDs over his or her normal life expectancy. The rules regarding RMDs are discussed in detail in Chapter 5, but for now it’s important to know that RMDs force money out of a tax-deferred or tax-free environment, into a taxable environment. And remember Mr. Pay Taxes Now and Mr. Pay Taxes Later from Chapter 1? Mr. Pay Taxes Later was the clear winner.

If you’re trying to figure out the most opportune strategies for naming beneficiaries of your IRAs, you should refer to Chapter 13 for an in-depth discussion on the subject, but here is a simplified explanation of the inheritance rules for a spouse:

The rules are not as generous if your beneficiary is not your spouse, and they may even change for the worse. (In fact, these rules could provide an incentive for committed couples who have not legally married, to do so.)

Even though we are not talking about Roth IRA conversions at this point in the book, the reasoning that goes into deciding to put money in a Roth 401(k) versus a traditional 401(k) is conceptually similar to the reasoning that goes into deciding to make a Roth IRA conversion. So, although you may be retired, the following analysis is relevant for retirees thinking about a Roth IRA conversion.

Additional Advantages for Higher Income Taxpayers

One great feature of the new Roth 401(k)/403(b) plan is that it allows higher income taxpayers to save money in the Roth environment. How does the advantage change in their situation? Figure 3.2 uses the same assumptions as Figure 3.1; except that Gary’s ordinary income tax rate has been increased to the current maximum of 39.6 percent, including the liquidation tax rate used for measurement.

In Figure 3.2, we discover that the Roth 401(k) advantage for a higher income taxpayer is greater than for the lower income taxpayer in the 25 percent tax bracket (Figure 3.1). The advantage has now become a huge 40.4 percent, or $338,352, after 40 years. Why such a large difference? There are several reasons why this happened, and they relate to the ever-changing tax laws. First, the maximum federal income tax rate was increased from 35 percent, to 39.6 percent. Second, there were several new taxes imposed on high income taxpayers. Higher earners (in 2014, single individuals whose adjusted gross income exceeds $200,000 or married taxpayers filing jointly whose income exceeds $250,000) are now subject to the Net Investment Tax, which adds on an additional 3.8 percent tax to certain investment income earned outside of the Roth account. High earners are also subject to a phase-out of their standard deductions and personal exemptions, which effectively increases their average tax rate. These and other factors all combine to make the Roth an even more attractive option for higher income taxpayers than in prior years.

Figure 3.2

Roth 401(k) Savings vs. Traditional 401(k) Savings RMD is Spent Annually

And guess what? The higher income taxpayer is more likely not to need to spend the Roth investments, thus making the long-term benefits more achievable.The bottom line is that the Roth 401(k) is dollar for dollar more valuable for the higher income retirement plan owner than a middle income retirement plan owner. The counter argument is that the amount of savings to middle income taxpayers, though smaller, is more meaningful in terms of the impact on their lives.

Effects of a Higher Liquidation Tax Rate

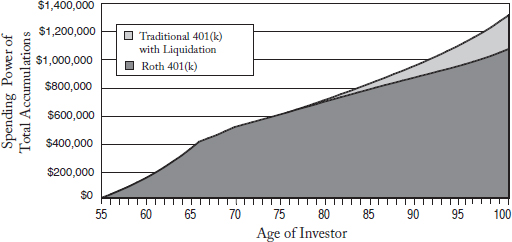

Let’s further consider the liquidation tax rate. This is a tax rate applied to remaining amounts in your traditional pre-tax retirement accounts if you were to liquidate your entire account. By applying the liquidation tax rate, you get a measure of what the account would be worth in after-tax dollars. You can think of it as a measure of the total amount you could withdraw from the traditional 401(k), an amount that changes as each year passes and your retirement plan grows. Suppose you didn’t handle your 401(k) rollover correctly – something we’ll cover in Chapter 6 – and you had to pay income tax on your entire 401(k) balance on April 15. Wouldn’t all this extra income you’ll have from cashing out the plan put you in a higher tax bracket? What happens to Figure 3.1 if we use a higher liquidation tax rate of 39.6 percent, for an average income level taxpayer? Figure 3.3 still reflects ordinary income tax rates of 25 percent on withdrawals, but incorporates a liquidation withdrawal taxed at 39.6 percent. The money that is withdrawn from the traditional IRA has been immediately reinvested in the same funds as the Roth IRA, but in an after-tax account. This line is called Traditional 401(k) with Liquidation on Figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3

Roth 401(k) Savings vs. Traditional 401(k) Savings Ordinary Tax Rate of 25% Liquidation Tax Rate of 39.6%

What we find is that the graphs are similar in their general trends. However, we can also see that the Roth now has a larger comparable advantage than in Figure 3.1. Not surprisingly, the tax consequences of liquidating the account at age 55 aren’t so bad because the balance in the 401(k) is relatively low. But if Gary liquidates his 401(k) when he is 95, the difference is significant. He would pay over $225,000 in additional income taxes if the account he liquidated is a traditional IRA as opposed to a Roth IRA. This shows that using a Roth 401(k) protects our nest egg from additional income tax costs should we need to spend an unexpectedly large amount of money in the middle of retirement, which might be the scenario for a retiree who needs to liquidate a large portion of his retirement plan in order to move into a retirement home or life care community.

The Roth 401(k) provides a level of safety from the income tax burden if a large liquidation is necessary, for any reason.Whatever the financial problem is, it need not be worsened by extra-high marginal income tax brackets.

What if Your Tax Rates Drop in Retirement?

A situation that makes a Roth 401(k) less appealing is when the employee earns a high income and is in a high tax bracket while working, but when he retires, he is in a lower tax bracket. Let’s assume that Gary has saved enough after-tax money from his paychecks that he is able to survive by spending only his savings, Social Security and the RMDs from his traditional 401(k), beginning at age 70.

If we now make a graph similar to Figure 3.2, but instead of continuing the 39.6 percent ordinary tax bracket throughout his retirement, we use a lower 28 percent tax bracket, and we also use a liquidation rate equal to the ordinary tax rate of 28 percent in retirement, we find the graph looks like Figure 3.4 below.

Figure 3.4

Roth 401(k) Savings vs. Traditional 401(k) Savings Ordinary Tax Rates 39.6% Before Retirement, 28% After Retirement Liquidation Tax Rate of 28%

Figure 3.4 illustrates that, in the early years, the traditional IRA has a definite advantage. The line for the traditional IRA hides the line for the Roth IRA, so I’ll tell you what you can’t see in the earlier years. After one year, the traditional IRA has an advantage of more than 10 percent. At age 65, the advantage declines to less than eight percent, and at age 75 to slightly more than six percent. The breakeven point happens at age 94, after which the Roth IRA has the advantage. Even more interesting is the fact that, after age 94, the Roth advantage grows at a much faster rate. The traditional IRA began with an advantage of more than 10 percent, and it took more than 40 years for the Roth IRA to overtake it and gain the advantage. Once the advantage was reached, though, it took only eleven years (age 106) before the Roth’s value is more than 10 percent greater than the traditional IRA. And at age 110, the Roth’s advantage has grown to more than 15 percent. It is not likely that you will live long enough to see the Roth’s advantage in this scenario, but if your plan is to keep the money in the tax-free Roth environment and then leave it to heirs who will do the same, the Roth is clearly the preferred vehicle.

Figure 3.4 is hard for many people to believe. How can the Roth become better with lower taxes in retirement? The answer lies in the fate of the original income tax savings generated by using the traditional 401(k). This money went into the after-tax investment pool where its growth became subject to income taxes. These taxes don’t seem like much: ordinary taxes on interest and smaller capital gains tax rates in retirement than were paid while working. But these taxes, even at their reduced rates, are disadvantaged over the long term in contrast to the Roth 401(k) where growth is entirely tax-free.

A Higher Liquidation Rate May Be Appropriate

Some readers may be skeptical of the fact that we used a 28% liquidation rate in Figure 3.2. Remember, the liquidation rate is the marginal tax rate that you would incur upon withdrawing, or cashing in, your entire IRA or retirement plan. What happens if you have a very large IRA or retirement plan? We have to apply a higher marginal rate to the traditional plan balances to allow for higher marginal rates if the entire IRA or retirement plan is cashed in at once, because the additional income from the IRA withdrawals will likely push you into a tax bracket that is higher than 28 percent.

A higher rate could also be used to illustrate the potential advantage your heirs could realize after your death from the continued tax-free growth of an inherited Roth IRA. The advantage to your heirs can be more than a few percent if the maximum tax-free growth is maintained over their life expectancy. We have extended these calculations over three generations, and have found in those cases that a Roth inheritance received by a grandchild can eventually be worth over 50 percent more than a comparable pre-tax fund inheritance. So, under the current rules, your heirs would be better off inheriting a smaller Roth account than a larger amount of pre-tax money. But those rules might change, as you will see in Chapter 5.

In any case, let’s look at what happens if we assume that the withdrawal pushes the taxpayer into the highest possible tax bracket, which at this writing is 39.6 percent.

Although it is difficult to see on the graph, the Roth has an advantage of $131 after the end of the first year. And by age 95, the Roth’s advantage has only grown by 5.83 percent, or about $50,000.

So the bottom line is that, for moderate to high income taxpayers, the Roth 401(k) is better.

Figure 3.5

Roth 401(k) Savings vs. Traditional 401(k) Savings Ordinary Tax & Liquidation Tax Rates of 39.6% Retirement Tax Rate of 28%

Extremely Lower Tax Brackets in Retirement

In a sobering illustration, however, we can see where the Roth 401(k) is not advantageous. Figure 3.6 assumes an individual in the 39.6 percent tax bracket while working and the 15 percent tax bracket in retirement. Maybe they were extravagant spenders during their early working years and neglected to save much in traditional retirement accounts. Maybe most of what they have is Roth IRAs and little else, for whatever reason. Figure 3.6 shows a different story.

Here the Roth 401(k) contributor went too far. The Roth is disadvantaged from the very first year, because the income tax savings afforded by the contribution to the traditional account in the early years offer a greater benefit than the income tax savings in the later years. And the disadvantage continues to grow, the longer the account is held. Some readers might argue that this scenario is not realistic, because an individual who is in the maximum tax bracket while working is not likely to be in the minimum tax bracket in retirement. Such individuals would more than likely be eligible to receive the maximum Social Security benefits possible, which when combined with other sources of taxable income, will push them into a higher tax bracket. So I created this worst-case scenario for the readers who believe that the Social Security system will be bankrupt by the time they retire, and their retirement income will come solely from their own savings.

Figure 3.6

Roth 401(k) Savings vs. Traditional 401(k) Savings Ordinary Rate of 39.6% Retirement & Liquidation Tax Rate of 15%

This graph does show that your retirement plans should include having an income that is not too much less than your income while working, if you want to get the tax benefits from the Roth. It may seem obvious that everyone should hope to avoid a significant decline in income during their retirement, but this is a point worth mentioning because there is a lot being published about the benefits of retiring to third-world countries where the cost of living is less than in the United States. If that is your plan, the tax deduction from traditional 401(k) contributions might be too good to pass up.

When Higher Liquidation Rates Should Again Be Considered

Even if you do fall into a much lower tax bracket after retirement, your heirs may not. And, if they were to inherit the Roth under current law, they could potentially reap continued tax-free advantages for decades. So let’s look at what happens if we have a taxpayer who is in the highest income tax bracket, who leaves a Roth account to an heir who is in the lowest income tax bracket. If the heir liquidates the account after decades of tax-free growth, a liquidation tax rate of 39.6 could be appropriate.

Figure 3.7 and related calculations show the Roth 401(k) retains an advantage of almost three percent until age 69, when the traditional plan begins to recover. By age 76, the traditional plan has the advantage due to lower taxes paid by the heirs upon withdrawals. Again, if these substantially lower income tax rates persist for long enough after retirement, the traditional plan ends up being significantly better as shown in Figure 3.6.

Figure 3.7

Roth 401(k) Savings vs. Traditional 401(k) Savings Ordinary Tax & Liquidation Tax Rates of 39.6% Retirement Tax Rate of 15%

What if You Need the Money, Not Your Heirs: Spending Down the Roth 401(k)

All the above figures may indicate that the Roth 401(k) is a good idea and can eventually result in huge gains for the family. But what if you need to spend your Roth account during your own lifetime? The quick answer is, if that is all you have to spend, without taxable income from any other source, you may be better off taking the original tax deductions on the traditional 401(k) as shown in Figure 3.6.

But what about a more balanced situation, where you have a pension income as well as Social Security, and your tax rate is 25 percent all along, as in Figure 3.1, but you need to tap into your nest egg, taking more than the RMD. Would it have been a mistake to have contributed to a Roth if you have to systematically deplete the account over time?

To answer this question, we prepared the graph in Figure 3.8, which is similar to Figure 3.1, but instead of taking only the RMDs from retirement accounts, we take $20,000 from the traditional 401(k) during ages 66 to 69, and $20,000 more than the resulting RMDs for each year thereafter.

Figure 3.8

401(k) Savings vs. Traditional 401(k) Savings Moderate Additional Spending

Figure 3.8 still indicates an advantage to the Roth 401(k) due to the tax savings which began in Year 1. The level of spending is higher in the earlier years, but actually becomes lower in the later years. This is because the larger withdrawals in the earlier years have reduced the account balance, so the RMDs in the later years are lower.

The result of this sooner-than-expected withdrawal rate is not significant to the decision of which is better. The Roth still grows its advantage to more than 66 percent, or $449,050, by age 95.

Let’s assume that your spending needs are even greater. This time we will begin to take $40,000 at age 66 and increase the withdrawal every year for inflation: This creates the graph shown in Figure 3.9.

Now the Roth advantage is less apparent. The traditional 401(k) plan runs out of money before age 82, but the Roth 401(k) plan runs out before age 84—a period of about eighteen months. It might seem like an insignificant difference, but if you were in this situation at age 83 and had no other money available to you, I think you would be glad you chose the Roth. The bottom line is that despite the excessive spending in retirement, the Roth 401(k) is still better than the traditional 401(k) plan.

Figure 3.9

Roth 401(k) Savings vs. Traditional 401(k) Savings Substantial Additional Spending

Conclusion

It is unlikely that the assumptions made in the above analyses will reflect your exact personal situation. The assumed rate of return I have used is very conservative (6%), and the differences between the Roth and traditional IRA will be even more pronounced if you earn a higher rate of return on your own investments. There will always be uncertainty regarding future investment rates, tax rates, and even your own spending. However, there is value in seeing objective numbers in different scenarios, and hopefully the above information can help you make decisions regarding your own retirement and estate plan. Seeing a qualified financial advisor who can personalize the advice for you would be the preferred course of action.

The Roth savings options can change people’s lives for the better. Subject to a few exceptions discussed above, if you have access to a Roth option in your retirement plan at work, I highly recommend that you take advantage of it, and if you can afford it, contribute the maximum allowed. Also, please keep in mind that this analysis is also quite valuable for someone interested in Roth IRA conversions because there are a lot of similarities in the calculations and the sensitivity of tax brackets.

Making It Happen

The Roth savings options

can change people’s lives for

the better. Subject to a few

exceptions discussed above,

if you have access to a Roth

option in your retirement plan

at work, I highly recommend

you take advantage of it, and

if you can afford it, contribute

the maximum allowed.

Notice, however, there is a caveat. I said, “If you have access.” Though Congress has made Roth 401(k)s and Roth 403(b)s available for employers to use, that doesn’t mean your employer has adopted these features or has made plans to do so. Speaking as an employer, the additional paperwork seems insignificant to me. I suspect the biggest reason more companies haven’t added a Roth 401(k) component to their plan is inertia. If you are an employee who is not being provided with options for a

Roth 401(k) or Roth 403(b), you should gently (or not so gently depending on your personality and the ofice politics) suggest that your employer adopt the Roth 401(k) or Roth 403(b) plan and allow you to participate.

In Notice 2006–44, the IRS provides a sample amendment for Roth elective deferrals, which should ease the burden for plan sponsors. If you are a retirement plan administrator or owner of a small business and if you have not already considered implementing a Roth 401(k) or Roth 403(b), you should strongly consider it. We did it in our own business and now, in addition to what I contribute to my employee’s retirement plan, each employee has the option of a Roth 401(k) or a traditional 401(k). The paperwork and costs were minimal.

A Key Lesson from This Chapter

For most readers, the expansion or entrée into the tax-free world of Roth 401(k)s and Roth 403(b)s is well advised and over the long term will be one of the best things you can do for yourself and your family.