Main Topics

KEY IDEA

A Roth conversion of even a portion of your traditional IRA or retirement plan can offer significant financial advantages.

The Roth Conversion Rationale

The Roth IRA was created as an incentive for Americans to save more for their retirements and was written in to law in 1998. Since that time, our office has made thousands of financial projections comparing the benefits of traditional retirement savings accounts to the Roth accounts. It has become apparent to us that, in general, Roth IRAs, Roth 401(k)s, Roth 403(b)s, and Roth conversions from traditional accounts usually result in more purchasing power for IRA owners and their families than traditional plans because they create tax-free growth. This is true even taking into account the tax expenses of a Roth conversion and the tax-deferred savings foregone by using a Roth account instead of a traditional tax-deductible retirement account. A traditional retirement plan, whether it is an IRA, a 401(k), 403(b), KEOGH, SEP, or 457 plan is funded with tax-deductible contributions from both you and/or your employer.

The money in these plans grows tax-deferred and is taxed when with-drawn. You may need to withdraw money from your IRAs and retirement plans to meet your living expenses before age 70½, in which case you will be taxed at that time. If you are fortunate enough to have enough after-tax dollars or other income that you don’t need to withdraw from your IRAs or retirement plans, you may continue deferring the taxes until you reach age 70½, at which time you will be required to begin withdrawing money from your retirement plans. In general, the distributions from your IRA and retirement plans are added to your other income, and you pay taxes on the total. You will have to pay income taxes on the withdrawals at your existing tax rate, or possibly a higher tax rate if the additional income pushes you into a higher tax bracket.

With a Roth conversion, you can change a traditional IRA or retirement plan, or just a portion of your IRA or traditional plan, to a Roth account. When you make the conversion, you have to add the amount of the Roth conversion to your income, and pay taxes on it. After paying the tax, you will have converted your traditional retirement account (or the partial amount) to a Roth account. And in doing so, you pay tax on your retirement income now. Why on earth would anybody want to do that?

The reason you might be willing to pay income taxes now is because all of the growth on the account from the day of the conversion and all withdrawals from the Roth by you or your heirs will be completely tax-free (after certain conditions are met). Maintaining the status quo and doing nothing is usually a less attractive alternative. Withdrawals from your traditional IRA, which will include your own contributions as well as the growth, will be taxed at future ordinary income rates.

Unlike a traditional IRA, there are currently no Required Minimum Distributions (RMD) from a Roth IRA for you or your spouse. With good planning, a Roth account will give you years of tax-free growth on the total investment. After you and your spouse both die, it is likely that you will have some Roth IRA dollars remaining in your estate. At that point, your children and/or the trusts you have established for your grandchildren will be required to withdraw money from their inherited Roth account. Those distributions might happen years after you converted the account, and they will be tax-free.

You may still be asking, “Who in their right mind would write the government a check when they don’t have to?” The answer is me, many of my readers and clients I have advised over the years, and, hopefully after reading this chapter, you too. The reason bears repeating: Under current law, the Roth IRA will grow income-tax free for the rest of your life, income-tax free for the rest of your spouse’s life, and income-tax free for the lives of your children, your grandchildren, and potentially even your great grandchildren.

To use an agricultural analogy, a Roth IRA conversion requires you to pay tax on the seed. In this case, the seed is the amount of the traditional IRA that you want to convert to the Roth IRA. You plant the seed (invest in your new Roth IRA) and, over many years, it blossoms and grows. Then when you, or your heirs, harvest the crop (the original investment and all of the growth), the harvest is income-tax free. The advantages of the Roth conversion, when circumstances warrant one, should not be under-estimated; it could mean hundreds of thousands of dollars – sometimes millions of dollars – of additional purchasing power for your family. And it even offers significant advantages to you, too.

The Secret to Understanding Roth Conversions: Valuing Wealth in Terms of Purchasing Power Instead of Total Dollars

The following section puts IRAs and Roth IRAs in a new perspective and may require a second reading to cement the concept. It is the key to understanding IRAs in general, and the Roth conversion illustrations that follow in this chapter. I call it “the secret” because very few people, including CPAs, financial planners and advisors, attorneys, and even Roth IRA commentators, know it. I believe understanding “the secret” is the first step in understanding Roth IRA conversions, and the nature of IRAs and retirement plans in general.

I believe that the best way to

measure wealth, or affluence,

is by assessing your total

purchasing power, not your

total dollars.

In the world of money, the general rule is that whoever has the most, wins. Right? We all want the most money we can possibly get our hands on. Well, I’m going to go out on a limb and suggest to you that having “the most money” is not the best way to measure your affluence or wealth. Don’t panic! I’m not getting metaphysical with you and suggesting people who have no money, but who have good health or a wonderful family, are rich (though they might well be). I believe that the best way to measure wealth, or affluence, is by assessing your total purchasing power, not your total dollars.

Let’s say you have $1 million in a traditional IRA. Even though you have that amount in dollars, you do not have $1 million in purchasing power. This is because the money in the traditional IRA is tax-deferred, not tax free, and you will have to pay income tax when you cash in that IRA. So, even though the face value of your account is $1 million, you have far less than $1 million available to you to travel the world, pay for your grandchildren’s education, give to charity, or to do whatever you choose. (I’m assuming that sending a big fat check to the IRS is not on your priority list)! Understanding the concept of purchasing power is critical to truly understanding the benefits of a Roth IRA conversion.

The Simple Math (Arithmetic) Behind the Secret

Let’s assume for discussion’s sake that you have $100,000 in a traditional IRA or retirement account. I typically refer to the money in those accounts as pretax dollars. Let’s also assume that the only other money you have is $25,000 outside of the IRA in a CD or other taxable investment. I refer to that money as after-tax dollars. For this example, I am also going to assume that you are in the 25 percent tax bracket. Your own tax bracket, while very important for determining whether and/or how much to convert to a Roth account, is not important for the purpose of understanding “the secret.”

When measuring money the conventional way, we would say that you have a total of $125,000 dollars: $100,000 in your retirement plan (pre-tax dollars), and $25,000 outside of your retirement plan (after-tax dollars). That is all well and good, and I agree that, in this simple example, $125,000 does represent the total number of dollars you have. I, however, submit to you that the more appropriate measuring tool of your wealth is purchasing power.

Continuing with the previous scenario ($100,000 of pre-tax money and $25,000 of after-tax money), let’s assume that you want to buy something that costs exactly $100,000. (Not a wise decision, certainly, but this is only an example)! You would have to cash in the IRA and pay taxes on the withdrawal. Assuming that you are in a 25 percent tax bracket, the tax due on the $100,000 withdrawal would be $25,000. In this example, conveniently, you have enough money in your after-tax account to pay the tax due on the withdrawal. And after you pay the taxes, you are left with $100,000 that you can use to make your purchase. So what does that mean? Well, even though you had $125,000 total dollars, after withdrawing the money from the retirement account and paying the required taxes, you have only $100,000 left to spend on whatever it was that you really wanted to buy.

In contrast, let’s assume you are starting with the same assets above ($100,000 in an IRA and $25,000 of after-tax dollars). You make a $100,000 Roth IRA conversion and use your $25,000 of after-tax dollars to pay the taxes on the conversion. That leaves you with a $100,000 Roth IRA and no after-tax dollars. On paper, you have less money than you did in the first example, but in this example, the money can be withdrawn tax free, so you also have $100,000 available to spend.

Do you see why I consider the two accounts that total $125,000 to be worth only $100,000 when measured in terms of their purchasing power? I would maintain that, at least on day one, the two investors have equal purchasing power. But if you just look at the numbers on paper, you might think that the guy who has $125,000 is richer than the guy who has the $100,000 tax-free Roth account.

Let’s compare Mr. Status Quo, who sits there with his $100,000 Traditional IRA and $25,000 after-tax account, to his identical twin brother, Mr. Roth IRA Conversion. Mr. Status Quo laughs when his brother converts his $100,000 traditional IRA to a Roth IRA, and liquidates his $25,000 after-tax account so that he can send money to the IRS to pay his large tax bill. Mr. Status Quo tells his brother that he should have his head examined. But on day one, Mr. Roth IRA Conversion still has the same purchasing power as Mr. Status Quo:

| Roth IRA value after conversion |

Traditional IRA |

|

| Non-IRA money* Total Dollars |

|

|

| Less taxes paid on IRA when withdrawn Purchasing Power |

|

|

* Mr. Roth Conversion used his non-IRA money of $25,000 to pay tax on the conversion.

For this example, we assume the liquidation rate (which is the rate of tax we have to pay when we withdraw our traditional IRA) is equal to the conversion rate (the rate of tax we have to pay to make a Roth IRA conversion). On day one, Mr. Status Quo and Mr. Roth IRA Conversion are equals when their wealth is measured in purchasing power. And, while Mr. Status Quo’s IRA (the $100,000) will grow tax–deferred, that growth will be taxed when he withdraws money from the account. The dividends, interest and capital gains on his after-tax account (the $25,000) will also be taxable. Mr. Roth IRA Conversion’s Roth account will continue to grow income-tax free.

Now let’s take this concept and apply it to you. Let’s assume that you are considering the advisability of making a Roth IRA conversion. Rather than using total dollars as your measurement tool, consider using purchasing power instead. You and/or your financial advisor complete the appropriate paper-work, and what used to be your $100,000 traditional IRA is now a $100,000 Roth IRA. (Please note that, in most cases, you don’t even have to change your investments to convert your traditional IRA to a Roth IRA). Sometime in February of the year following the year that you make the conversion, you will receive a Form 1099 that in effect says, “Please add $100,000 to your taxable income for the year you made the Roth IRA conversion.” Continuing with our simple example, you pay your $25,000 tax (or 25 percent) on your additional income. In this case, you have $25,000 of after-tax money to pay your tax bill. The analysis would be significantly different if you had to pay the tax by withdrawing money from a traditional IRA or retirement plan, but we’ll talk more about that later in this chapter.

So what do you have now? You have $100,000 in your Roth IRA. If you cash in your Roth IRA, how much tax do you have to pay? None, as long as you meet the conditions that are discussed in Chapter 3. After making the conversion, you have $100,000 of purchasing power. Without the conversion, you would have $125,000 but only $100,000 of purchasing power because of the taxes that you will owe when you cash in your IRA. Can we agree that, if your measurement tool is purchasing power rather than total dollars, and the tax rate is constant, making a Roth IRA conversion will not diminish your purchasing power as of day one? (I think I have hammered that home)!

This is a critical concept. Critics, analysts, and even some authors who hold themselves out as IRA experts hold that Roth IRA conversions are great for young people because young IRA owners have so many years going forward for tax-free growth. Traditional thinking also holds that a Roth conversion for an IRA owner who is 60, 70 or 80+ is a bad idea because the IRA owner will not have enough years of tax-free growth to make up for paying the income tax on the conversion. That’s what most financial writers think, and I take great exception to this traditional thinking. The common flaw in their logic is that many software programs (including software programs from huge financial companies that should know better) compare the results using total dollars, rather than purchasing power. When you use purchasing power as your standard, it is clear that, on day one, the individual who made the conversion is no better off, but also no worse off. And if the account grows in value, the individual who made the conversion is clearly better off, because the gains on the Roth account are tax-free.

Does this suggest to you that, perhaps, even for an older individual, a Roth IRA conversion might be an acceptable transaction? You could be 90 years old, do a Roth IRA conversion and, given the previous assumptions, you would have a level of purchasing power equivalent to your pre-conversion purchasing power. You could be 110 years old, and it might be very appropriate for you to make a Roth IRA conversion. Admittedly, it is more beneficial for a younger person to make a Roth IRA conversion than an older IRA owner, because the younger person will likely have more years to enjoy tax-free growth. But, just because the results are better for a younger person doesn’t mean that a conversion is a bad idea for an older IRA owner. Furthermore, while older IRA owners are likely to derive some benefits from the conversion during their lifetime, their heirs might enjoy life changing increases in wealth because of their action.

This does not mean that Roth IRA conversions are a good idea for everyone. Roth IRA conversions can be a very bad idea, given a specific set of circumstances. Before we recommend that our clients make a Roth IRA conversion, we run the numbers first to make sure that the conversion will benefit them and also to determine what the optimal amount for them to convert would be. What follows next is a discussion of who qualifies to make a conversion, and the factors we need to take in to consideration before recommending a conversion for you. The illustrations that follow later in this chapter show how those factors can produce dramatically differing results for our clients.

Who Qualifies for a Roth Conversion?

Prior to 2010, individuals with adjusted gross incomes in excess of $100,000 were not permitted to make Roth IRA conversions. This law was permanently repealed in 2010, and now anyone, regardless of their taxable income, can convert any portion of their traditional IRA to a Roth. In addition, you may now convert your retirement plan such as a 401(k) or 403(b) directly into a Roth IRA if you are retired. Under current laws, an inherited 401(k) retirement plan may also be converted to Roth 401(k) status; however, an inherited IRA is not eligible for conversion. And as discussed in Chapter 3, if your plan allows it, you may now also convert some of your own 401(k) or 403(b) into a Roth 401(k) or 403(b) while you are still working. So, if you were ineligible to convert in the past because of the income limitations, or because all of your retirement assets were or still are in your 401(k) or 403(b) plan at work, you may want to revisit the concept again.

Factors to Consider before Converting to a Roth IRA

The potential for tax-free growth is so compelling that all taxpayers who have substantial IRA or retirement plan balances should consider converting at least a portion of them. As I mentioned at the outset of this chapter, a Roth conversion is one of the rare actions that contradicts my advice “Don’t pay taxes now, pay taxes later.” This is because by paying the associated taxes now, you avoid additional taxes later. However, many factors must be considered pertaining to both you, as the IRA or retirement plan owner, and to your beneficiaries, before making a Roth conversion. Let’s look at the major factors.

The potential for tax-free

growth is so compelling

that all taxpayers who have

substantial IRA or retirement plan

balances should consider

converting at least

a portion of them.

If you are the IRA or retirement plan owner, you need to consider all of the following:

Regarding your IRA’s probable beneficiaries, you need to consider these factors:

That is quite a list of things to consider, which is why we strongly recommend that you consult with a qualified financial advisor or CPA who can “run the numbers” prior to making any decisions about how to proceed. In our practice, we typically have the client in the room while we are running the numbers. This way, the client sees what we are doing and can insert their own “what if ” scenarios as we work.

Also Consider Current and Future Income Tax Laws

Obviously, income tax laws are significantly important for you and your heirs when planning for Roth conversions, including potential future tax rates and laws. If you are considering a conversion, one thing you need to be aware of is that President Obama would like to see some of the benefits of the Roth accounts eliminated. Historically, his budget proposals have included a provision to “harmonize” the rules of Roth IRAs with those of traditional IRAs, requiring that the original owners start mandatory withdrawals at age 70½. To make matters worse, President Obama and the Republican House would also like to force beneficiaries of IRAs or Roth IRAs to withdraw the balance within five years of the original owner’s death. This provision will be introduced as part of the President’s 2016 budget proposal. If it is passed, the outcome will be that your children (or any other non-spouse beneficiary) will only be able to enjoy the tax-free growth in the Roth account for five years after your and your spouse’s death. However, even if the law does pass, the Roth IRA conversion will, for many if not most taxpayers, still be very favorable but admittedly not as favorable as with existing laws where the heirs can continue the Roth’s taxfree growth for the rest of their lives. Billions of dollars have been converted from traditional IRAs to Roth IRAs and, if these changes are made in to law, my opinion is that the beneficiaries of existing accounts would have to be grandfathered under the old rules—meaning that, if a beneficiary inherits an account before the law is changed, they will be subject to the old rules. Many clients and readers would like the “grandfathered” accommodation to apply to anyone who established a Roth prior to the proposed law’s passage. That won’t do it. The IRS doesn’t care. If you are kicking when they change the law, your heirs will have to suffer with the five year rule. If you die before they pass the law, then your heirs may continue to “stretch” either the inherited IRA or inherited Roth IRA over the life of the beneficiary.

Is the law likely to change? I don’t know, and I hate to bet on what Congress may or may not do. I do, however, think there is at least a 50 percent chance that the ability to stretch both traditional and Roth IRAs will be repealed within this generation’s lifetime. To be fair, similar proposals were included in previous budgets and they did not pass, but remember what happened in 2013. The President wanted the stretch IRA and stretch Roth IRA to be repealed, and the Republican House voted for the proposal. Only the Democratic Senate stopped the repeal. Now that we no longer have a Democratic Senate, if the proposal comes up again, as I suspect it will, it will likely pass.

So, how does this potential change in the treatment of the inherited Roth IRA impact your Roth IRA decisions? What we do in our office is try to convert only an amount that will help or, at worst, be a breakeven for the IRA owner and their spouse. Any additional benefit your heirs will realize should be regarded as a bonus, not the main reason for the conversion. None-the-less, it is true that even if the law is changed and the stretch is repealed, and you made conversions with the intention of only benefitting you and your spouse, your children or other heirs will still be better off. What I no longer recommend is that you factor in the long-term “stretch Roth IRA” that the kids and grandchildren would enjoy for their entire lives in determining how much you convert. For example, let’s assume the appropriate person “runs the numbers” and determines you are a little worse off if you make a conversion, but under current law, your children and grandchildren would be better off. In the past, I might have leaned toward the conversion, but now I would lean against it.

The Roth Conversion Decision Analysis

Should you keep your traditional IRAs, or should you convert them to Roths? The examples that follow, quantifying the Roth’s advantage over not making a conversion, will span three generations of Roth IRA owners: the original IRA owner (most likely you), the child of the original owner, and the grandchild of the original owner. While many factors need to be taken in to consideration, including weighing the advantages to each generation, the bottom line is that the future tax savings on the tax-free growth of the Roth IRA generally out-weigh the benefits of a tax-deferred traditional IRA combined with after-tax investments—assuming those after-tax investments are used to pay the income tax on the conversion.

Readers have questioned our math. They say that if all our assumptions are steady (interest rate, tax rate, growth, etc.), then the Roth IRA conversion ends up being a breakeven or even a loss for the IRA owner. I agree that would be true if you paid the tax on the conversion from the IRA itself. However, if you pay the tax on the conversion with after-tax dollars, the math favors the conversion -especially if the benefit is measured in terms of purchasing power. This becomes even more apparent once the traditional IRA owner turns age 70½ and is required to take minimum distributions from the account. The Roth account continues to grow tax-free. It even grows in cases where the tax on the conversion was paid from the IRA itself. The longer the time horizon for tax-free growth, the greater the benefit a conversion can provide.

If you do not have the money

to pay the income tax on the

conversion from funds outside

the IRA, then my advice would

change—don’t do a conversion.

If you are like many of our clients, however, your wealth is primarily in your retirement plans and traditional IRAs. If you do not have the money to pay the income tax on the conversion from funds outside the IRA, then my advice would change—don’t do a conversion, or do a much more conservative conversion. Another instance where I would not recommend making a Roth IRA conversion would be if you plan to leave all your money to charity. The charity doesn’t have to pay taxes anyway and will not benefit from the tax-free growth of the Roth IRA, so you will have paid tax on the conversion needlessly.

A Series of Small Conversions Rather than One Big Conversion

In Chapter 2, we introduced the advantages tax-free Roth IRAs have over traditional tax-deferred IRAs. There were two important points to remember:

1. The growth in the Roth IRA is tax free.

2. The Roth eliminates the problem of the taxable growth on the tax savings from a deductible IRA contribution.

These advantages also apply to Roth conversions. A conversion, with time, results in more purchasing power than in a tax-deferred IRA account that is combined with other nontax-sheltered, after-tax investments (but even on day-one is a breakeven). Additionally, there are no RMDs from the Roth IRA (for either you or your spouse) as there are with traditional IRAs. If you don’t need the money, the Roth account keeps growing tax-free in contrast to a traditional IRA which has RMDs—eventually forcing the IRA owner to pay the tax and then to invest whatever is left in after-tax investments.

Depending on the circumstances of the individual contemplating the Roth IRA conversion, I often recommend a series of partial conversions of their traditional IRA to a Roth IRA—one every year over a period of years. How much to convert is a significant decision because if you convert a large amount, it could result in a high tax rate on the conversion. Your best strategy might be to convert just enough to bring your taxable income to the top of your present tax bracket, and then repeat that process in subsequent years. This keeps the conversion-related taxes to a reasonable amount, and it prevents you from paying income taxes on the conversion at a high rate.

Your best strategy might be

to convert just enough to

bring your taxable income to

the top of your present tax

bracket, and then repeat that

process in subsequent years.

For families in the right situation, even a modest conversion could mean tens of thousands of dollars (in today’s dollars) in additional purchasing power for your family.

MINI CASE STUDY 7.1

Benefits of a Roth IRA Conversion

Suppose you have a financially identical twin, and you are both 65. Because you read Retire Secure! and after consulting with your financial advisor, you decided to make a series of Roth IRA conversions that total $250,000. Your twin, however, never even learns about the possibility of a Roth IRA conversion. Every year for five years from the time you are 65 to 69, you convert $50,000 (growing at 6 percent each year) from the traditional IRA to a Roth IRA. Your conversion amounts add to your taxable income each year. For this example, we will assume your total income (and perhaps Medicare premium increases) causes you to pay 28 percent tax on each conversion amount. (We use 28 percent because we assume you are usually in the 25 percent bracket. The extra income from the conversion will generally increase your tax bracket in the year of conversion). You pay the tax on the conversion from money outside of your IRA. Your financial twin, on the other hand, doesn’t make the conversion. He keeps his after-tax money and invests it in a diversified portfolio, and enjoys investment income on the same amount of money that you sent to the IRS. For simplicity, we will assume 75 percent of the investment income is taxed at the preferred rates for long-term capital gains and qualified dividends. The other 25 percent of investment income is taxed at ordinary tax rates.

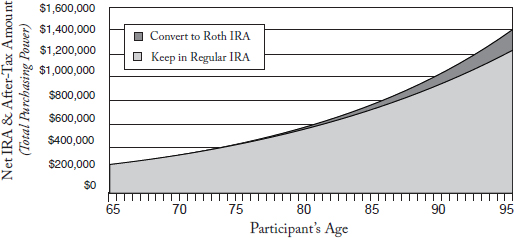

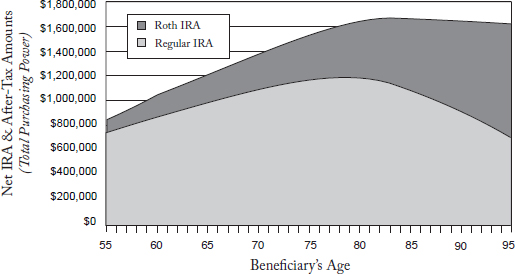

You and your twin invest identically, and you each receive a 6 percent return on your investments. For purposes of comparison, though, I do not want you to compare the total dollars in each of your accounts. Doing that would make no sense, because the with-drawals from his traditional IRA account will be taxable, and with-drawals from your Roth IRA account will be tax-free. Instead, I want you to think in terms of that very important concept called purchasing power, or the amount of goods and services that you and your twin can each buy, after you have both paid any income taxes on traditional IRA balances. The graph in Figure 7.1 on the next page shows the amount of purchasing power over time for both of you.

The graph in Figure 7.1 reveals that, after the very first conversion, your Roth account has a small advantage over your twin’s traditional IRA. This advantage grows over time. When all of your IRA is converted after five years, you will have $7,330 more in spending power than your twin. At age 90, you will have $113,601 in more spending power.

This is a significant advantage but, remember, you paid the higher tax rate of 28 percent on the amounts you converted because your income was higher than usual during those five years. If you had left the money in the traditional IRA like your twin and withdrew only your RMD, the tax rate on those with-

Figure 7.1

The Roth Conversion Advantage

The assumptions for this graph include the following:

1. Each investor starts on 1/1/2015 with $250,000 in an IRA and $68,400 in after-tax investments from which the taxes on the conversions are paid.

2. Investments earn a 6 percent rate of return.

3. Ordinary federal income tax rates are 25 percent for regular IRA minimum distributions and on one-quarter of the investment income on the after-tax accounts.

4. Federal taxes on the other three-quarters of the investment income in the after-tax accounts is taxed at the preferred 15 percent rate.

5. State income taxes of 3 percent are levied against after-tax investment income, but not on the conversion amount or IRA withdrawals (similar to tax laws in Pennsylvania).

6. Tax on the conversion and for measuring the purchasing power of the remaining traditional IRA balances is 28 percent.

7. Required Minimum Distributions from the regular IRA are reinvested with the after-tax investments.

8. No withdrawals from the investments are made.

drawals would have been only 25 percent. The results in Figure 7.1 show that, even if you are pushed in to a higher tax bracket during the years of conversion, the conversions can still result in an advantage over time.

MINI CASE STUDY 7.2

Take Advantage of the Window of Opportunity for Roth IRA Conversions

Many new retirees find themselves in the fortunate position of being in the lowest tax bracket they will ever be in for the rest of their lives. You no longer have the income from your job. If you use our recommended strategies for taking your Social Security benefits (please see www.paytaxeslater.com for details on those), you will likely delay applying for your benefit until at least age 66. If you do receive benefits earlier, they might be lower than they will be when you turn 70. As we talked about in Chapter 4, you will be spending after-tax dollars first, which is likely to result in a smaller tax impact than if you spent IRA dollars. Assuming you have not reached age 70, you will have no RMDs on your IRA. When all of these factors are taken in to consideration, there is a good possibility that your income will be much higher when you are 70.

These years of low income tax rates between the time you retire and the time you are required to begin taking minimum distributions can be an optimal time to make Roth conversions. There could also be other times when your income is temporarily lower than at other times. One example might be a lay off where you aren’t working for a year. Another might be a significant medical expense that will lower your taxable income. We call these times, as well as the more common occurrence of the time between retirement and age 70½, a “window of opportunity” to make Roth conversions at lower income tax cost.

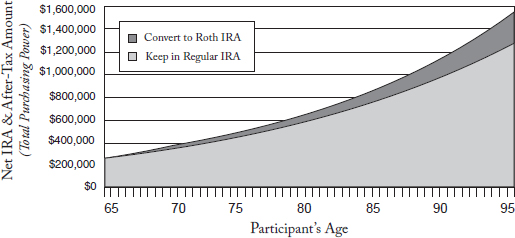

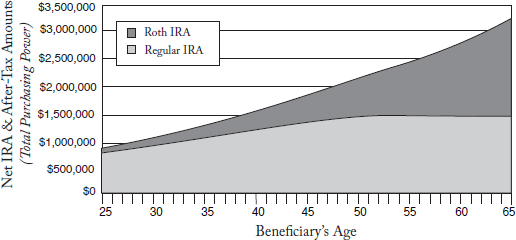

The following example shows what happens if, during the conversion years, you are in a lower tax bracket than you might expect to be during your later retirement years. This can happen if you delay starting your Social Security benefits, and you do not need to take taxable IRA withdrawals to meet your spending needs. Using the same starting point as in Mini Case Study 7.1, we will assume half of the conversion amounts are taxed at 15 percent and half at 25 percent for an average conversion tax rate of 20 percent. This gives your financial twin a small advantage in the early years because his long-term capital gains and qualified dividends will escape federal income taxes completely during the five year period he is in the 15 percent tax bracket. Since your income is higher from doing the conversions, there is still the 15 percent tax for you on the longterm capital gains and qualified dividends during those years.

Figure 7.2

The Roth Conversion Advantage Using a Window of Opportunity

The graph in Figure 7.2 reveals that there is a larger advantage to the Roth conversions that grows over time. After five years, when all of your IRA is converted, you will have $28,546 more in spending power than your twin. At age 90, the conversion advantage has grown to $167,480. This is a much better advantage than in Figure 7.1 because you were able to take advantage of temporarily lower income tax rates before you would have been required to start distributions on your traditional IRAs and retirement accounts.

These results indicate that the Roth IRA can offer significant advantages over the course of a lifetime for the smart twin who made the conversion. The results shown in Figures 7.1 and 7.2 may even understate the advantages of the Roth IRA conversion because they do not consider your beneficiary’s time frame for taking distributions from the inherited Roth IRA. Your beneficiary may continue to receive tax-free growth from the inherited Roth IRA, as compared to the tax-deferred growth of the traditional IRA and taxable growth of any after-tax accounts.

Looking at Figure 7.2, if you survive to age 95, the advantage would be $270,632. This advantage is even greater than the $250,000 beginning balance of the IRA! Even if you do not think you will live to that age, there will be continued advantages that can grow dramatically for your children or grand-children after they inherit your Roth IRA.

So, what will the situation look like if we extend the time frame to include a child as a beneficiary?

MINI CASE STUDY 7.3

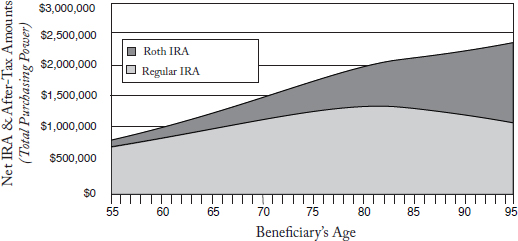

Roth IRA Advantage to the Beneficiary

Figure 7.3

Roth IRA Advantage to the Child Beneficiary After Using the Window of Opportunity

Let’s return to our example of you and your financial twin. Suppose you convert your $250,000 IRA to a Roth IRA over five years as in the above examples for Figure 7.2, using the window of opportunity to lower the tax on the conversion. Your twin does not do the conversions and you both die at age 85, which is 20 years after you began your Roth IRA conversions. You and your financial twin both have a 55-year-old son, and you each leave your money to your son.

At the time he dies, your twin has assets with a purchasing power of $747,944. This consists of his traditional IRA of $399,563 plus after-tax funds of $460,259, minus an income tax allowance (how much tax will be owed) on the traditional IRA of $111,878. If you die on the same day, your purchasing power is $851,412. You’ll have $801,784 in your Roth IRA and $49,628 of after-tax funds – the after-tax funds come from tax savings you realized from the conversion. And, since your account is a Roth, there is no deduction needed for an income tax allowance.

Figure 7.3 shows that your son, who inherited the Roth IRA, will eventually be left with nearly twice what your twin’s son, who inherited the traditional IRA, will have.The numbers are even more compelling. By the time your son reaches age 85, he will have $2,145,237. Your nephew, whose father did not make the conversion, has only $1,352,565. The conversion created an advantage to your son of $792,672 which is over three times the amount of the original IRA. The benefits of Roth IRAs to the second and third generation can be so significant that much of our planning used to be done considering children and grandchildren, but that is no longer automatically the case. We’ll cover the reasons why shortly.

Effect of the Proposed Five-Year Distribution Rule on Inherited Accounts

Remember President Obama’s proposed law change which would require a non-spouse beneficiary of an IRA or Roth IRA to withdraw all the funds with-in five years? If it is passed, will making conversions have been a mistake? Figure 7.4 demonstrates what would happen if both children inherited the IRAs at their age 55 (as in Figure 7.3) and withdrew their RMDs over five years.The withdrawals made by your twin’s son will be taxable and, in order to keep his tax rates as low as possible each year, he withdraws a relatively equal amount each year until the IRA is liquidated. Even though he tries to minimize the taxes, your twin’s son’s required distributions over the five years increases his income taxes on the distributions to 28 percent for each of those years. (With-out the five-year rule, Figure 7.3 his income tax rate was 25 percent). Your son, however, doesn’t have to worry about taxes. He keeps all of the money in the inherited Roth IRA account until the very last day of the fifth year, so that he can maximize the tax-free growth, and then withdraws the entire amount tax-free. (We have kept the same spending as in Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.4 on the following page shows that by the time the children reach age 85, the child of the twin who did not make the conversion has $1,091,930 in after-tax funds whereas the child who inherited the Roth IRA has $1,665,469 — a conversion advantage of $573,539. This advantage is less than in Figure 7.3, but is still significant even if the inherited IRAs and Roth IRAs must be liquidated in five years. If the five-year rule is implemented, the

Figure 7.4

Roth IRA Advantage to the Child Beneficiary Under Proposed 5-Year Distribution Rules

advantage to the Roth is 72.3% of the advantage that the beneficiary would be able to enjoy if he had been able to leave the money in the account.

The downside of the five-year rule is that the child ends up with much less money at age 85 than without the five-year rule. With the Roth IRA, he ends up with $1,665,469 instead of $2,145,237. This is because the money that had been in the Roth is forced into a taxable account. At age 85, the child will have paid an extra $479,769 in taxes that he otherwise would not have had to pay, if he had been able to leave the money in the Roth account.

I should point out that, with larger inheritances of traditional IRAs and Roth IRAs of perhaps $1,000,000 or more, the traditional IRA distributions could be so significant that, when all the child’s income is considered, the child beneficiary may actually have his tax rates pushed as high as 35 percent during the years when he is forced to take distributions. If we had used the 35 percent tax rate on the traditional IRA withdrawals for the child in the above graph, the conversion advantage would be $690,757 by age 85. This is less than the $792,672 advantage without the five-year rule, but still maintains 87 percent of the significant conversion advantage.

The conclusion you should draw from this analysis is that the five-year rule is not welcome because it subtracts substantially from your children’s IRA and Roth IRA inheritances. It should not, however, deter you from implementing a well thought out Roth conversion plan.

Additional Advantages of Naming Grandchildren as Beneficiaries

As I showed in Figures 7.3 and 7.4, the results of Roth conversions are quite favorable using a child as your beneficiary. However, under current rules, the results for a grandchild beneficiary are even better because of the lower RMDs of an inherited IRA or inherited Roth IRA for a younger person. If the five-year rule is made in to law, it would negate this additional advantage for the grandchild. However, there is the possibility that if the IRA or Roth IRA is inherited before such rule goes into effect, the five-year rule may not apply as existing inherited accounts may be exempt from the rules. In other words, existing inherited accounts would be grandfathered under the old rules assuming you or your spouse die before they change the rule. But, since we don’t know when or if the law is going to change, let’s look at what happens if a third-generation beneficiary inherits a Roth account.

Figure 7.5 shows the results if the beneficiary of your IRA is your 25-year-old grandchild instead of your 55-year-old child. The assumptions are similar in other respects to Figure 7.3, and your grandchild is assumed to have the same after-tax spending amounts as in the example of your 55-year-old child.

Figure 7.5

Roth IRA Advantage to the Grandchild Beneficiary

Figure 7.5 shows that your grandchild is much better off with your Roth conversion than without it. Let’s revisit my “secret,” or the idea of purchasing power, as it would apply to Figures 7.3 and 7.5. After 30 years from inheritance, and assuming an inflation rate of 3 percent, the relative purchasing power advantages from the Roth conversion are as follows:

| Advantage in Future Dollars | Advantage in Today’s Dollars | |

| Child as beneficiary | $ 792,672 | $ 180,814 |

| Grandchild as beneficiary | $ 1,042,281 | $ 237,752 |

After 40 years from inheritance, the graphs show the relative purchasing power advantages from the Roth conversion are as follows:

| Advantage in Future Dollars |

Advantage in Today’s Dollars |

|

| Child as beneficiary | $ 1,263,174 | $ 214,402 |

| Grandchild as beneficiary | $ 1,889,653 | $ 320,737 |

The advantages shown in the tables, even in today’s dollars, are a large percentage of the beginning balance of the IRA converted for the child and even more than that for the grandchild. The conclusion here is that, under current law, there is much to be gained by your beneficiaries from Roth IRA conversions, especially when they are able to continue the tax-free growth in the inherited Roth IRA.

Tax-Free Roth Conversions Are Possible

Anyone who can convert in a tax-free manner an amount from a traditional IRA or retirement plan that is growing tax-deferred to a Roth account that will be tax-free should do so. There are almost no good reasons not to do so.

Anyone who can convert

in a tax-free manner an

amount from a traditional

IRA or retirement plan

that is growing tax-deferred to

a Roth account that will be

tax-free should do so.

New laws in 2014 allow retirement plans such as 401(k)s and 403(b)s to segregate your after-tax contributions with separate accounting. If your plan does this, and you have after-tax contributions (basis) in your own account, you may now be able to convert your basis to a Roth IRA without having to use the aggregation rules. If your plan rules permit you to do such a conversion, those basis amounts can be, and should be, converted to a Roth IRA tax free.

Also, there is no time limit on how long you must keep your money in a traditional IRA before you convert it to a Roth IRA. Taxpayers without other taxable traditional IRAs, whose incomes are too high to make a direct contribution to a Roth IRA can contribute the maximum to a non-deductible traditional IRA and then convert it immediately to a Roth IRA, tax-free! These rules are discussed in detail in Chapter 2.

Generally, the amount you convert from a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA is taxable, but if you have “basis” in your IRA from non-deductible contributions, a fraction of the total may not be taxable. It is usually prudent to have a professional calculate the amount of the conversion that is taxable because the IRS’s aggregation rules consider the values of all of your traditional IRAs and ultimately make only a part of the conversion tax-free. And here is another important point. Please make sure you do not roll over a retirement plan to a traditional IRA in the same year that you do this tax-free conversion of an IRA contribution. The aggregation rules use end-of-year balances rather than at-the-time-of-conversion balances when calculating the amount of the conversion that is taxable, and your IRA balances will be higher after the rollover.

Even if you are subject to the aggregation rules, your basis in your IRAs will make part of the conversion tax-free. If the amount of your basis is significant, the taxes due on your conversion will be reduced. This provides an incentive to do the conversion sooner rather than later, because future growth of your traditional IRAs will make the conversion taxes higher.

Opportunities and Challenges for Higher Income Taxpayers to Move into the Roth Environment

For the very high income, top tax bracket individual, the benefit of a Roth IRA conversion is potentially phenomenal. Because of increased tax rates in 2013, high income earners are in a much better position to take advantage of the taxfree growth in a Roth than in previous years. By paying taxes on a conversion with after-tax money, they can reduce balances in their after-tax accounts that generate taxable income each year. This is a subtle but significant point. Those after-tax amounts are now subject to the higher capital gains tax rate of 20 percent instead of 15 percent and there is an additional 3.8 percent net investment income tax imposed on after-tax investment income. The top ordinary income tax rate has been increased to 39.6 percent, up from 35 percent. Higher income taxpayers also face a phase-out of itemized deductions and personal exemptions. It is these high taxes and limitations that make the cost of obtaining Roth IRAs a much more expensive proposition for high income individuals. Though we like to “run the numbers” for almost all Roth IRA conversion recommendations to optimize the amount and the timing, it is especially critical and frankly difficult for us, to do so for high income taxpayers.

For middle income taxpayers, large Roth conversions are relatively more costly as it can push their incomes up into those new higher tax rates. Lower or middle income individuals can also push themselves into a much higher tax bracket if they make a significant conversion.

The silver lining is that taxpayers who are already in the highest tax bracket cannot pay higher taxes! High income taxpayers are also likely to have the money to pay the taxes on the conversion from outside the IRA or retirement plan. Ultimately, the wealthy are also the most likely to be able to take advantage of a long time horizon of tax-free growth, because there is a reduced chance that they will need to spend that money. This means that high income taxpayers are frequently better candidates for large Roth conversions than middle or lower income taxpayers.

Prior to 2010, higher income individuals were not permitted to make Roth conversions as there was an income limit on conversions. Now there is no limit – but for how long? It is possible that new laws could limit Roth conversions again. And our analysis has shown that over a generation—passing the Roth from parent to child—a taxpayer’s family could benefit by as much as twice the amount converted or more. So, I strongly recommend wealthy readers to “run the numbers” with the help of a qualified advisor, to see if they can take advantage of the opportunity to do a Roth conversion while they can.

Rates of Return Affect Conversion Advantages

It should be noted that the above examples calculating advantages to Roth conversions all assumed a 6 percent rate of return. If we had used a higher rate of return such as 8 percent or 10 percent, the advantages would be much higher. Since equities have averaged over 10 percent returns over the last 50+ years, it is possible, even probable, that long-term money invested in Roth IRAs could earn far more than 6 percent in the very long run.

Conversely, if your rate of return is less than 6 percent, the advantages will be smaller. If you were to invest in CDs or savings accounts and earn 1 percent on your Roth money, the benefits of conversion may not be worth it. If you are conservative and have a largely fixed income allocation for your traditional IRA and other assets, we generally recommend that you consider a more aggressive investment allocation for your Roth IRAs because of the likely longer time horizon for number of years invested before distributions are taken out.

Losing money in the Roth accounts is even worse. But a decline in investment values in a Roth account can also present a very interesting opportunity, called a recharacterization.

The Downside of a Roth Conversion

The analysis thus far has assumed that your investments will grow over time. Even if the rate of growth is slower than I assume, you would still be better off, just not by as much. But what if your converted investment drops significantly after you make the conversion? Then, you would not be a happy camper and my advice to make a Roth IRA conversion would have hurt you, not helped you. The fear of losing money on investments is on everyone’s mind as we experience such volatility in the market.

The traditional response is that if you wait long enough the investment will recover. But, what if it doesn’t? What if you just decide it was a mistake. Are there steps you can take if the investment goes down soon after you make the Roth IRA conversion?

Yes. In short, you can recharacterize your Roth IRA conversion. However, please note that you cannot recharacterize a conversion inside your 401(k) or 403(b) to a Roth 401(k) or Roth 403(b). Recharacterize is the formal jargon to describe undoing your conversion. You can recharacterize a Roth IRA conversion by October 15 of the year following the year of the conversion. Why would you do that? Recharacterizing doesn’t help you recover the loss in your investment, but you can recover the taxes you paid on the original conversion by filing an amended return. Doing so would put you in a position similar to where you would have been if you had not completed the Roth IRA conversion in the first place. Your investment will have decreased in value whether it was in the traditional IRA or the Roth, but at least you will not have paid taxes unnecessarily on the conversion.

Now here’s the exciting part. After you recharacterize your Roth IRA that has gone down in value, you can, after a waiting period, make another Roth conversion of the same account. Why would you go through all that paperwork again? The answer is simple. If the account is converted again while the value is down, your tax liability to the IRS is greatly reduced.

There are waiting rules regarding these “reconversions” of IRAs. You must wait until the next calendar year (or 30 days, whichever is longer) to do another conversion of the same money. You can avoid this restriction, though, if you do the second Roth conversion to a new Roth IRA account before you do the recharacterization of the first account. But wait! Here’s another rule: you need to be careful not to move the recharacterized money back into the same IRA from which it was converted. If you do, the waiting periods will apply.

Partial recharacterizations are also permitted. I frequently have clients, even in good investment years, do a partial recharacterization. For example, let’s say that we recommended you convert no more than $50,000. If you convert more, your income will come very close to the limit of $170,000 where you would owe additional Medicare premiums. Because of an unexpected year-end capital gain in one of your mutual funds, though, your income including the conversion amount ends up being $189,500.

Is there any way to avoid the increase in your Medicare premiums? You bet! You can recharacterize 40 percent (or $20,000) of your conversion amount. Then you would only be taxed on the $30,000 of the conversion you kept. Your income would be $169,500 and you would avoid additional Medicare premiums. Please note that, if you recharacterize a Roth IRA, you must move back to the traditional IRA not only the conversion amount you wish to undo but also any growth it earned. If it declined in value, less will be moved back. It makes sense to discuss recharacterizations with your tax advisor before you finalize your tax return if you do significant Roth conversions.

This hindsight created by the recharacterization option is a wonderful safety net and, if you are “on the fence” about whether to do a conversion or not, it provides incentive to do the conversion. You can wait to see if it grows or not, and if you change your mind, you can undo it.

It should be noted that some tax proposals set forth for discussion recently have included a rule to prohibit such recharacterizations of Roth conversions. Please consult a well-informed advisor to stay on top of any such rule changes that may occur.

Fair warning: Please don’t overdo this Roth conversion and recharacertizing strategy unless you are prepared for a few headaches at tax-time.

MINI CASE STUDY 7.4

Recharacterizing the Roth IRA Conversion

Carrie Convert converts $100,000 of her traditional IRA in July 2015. She files her tax return in April 2016, reports an additional $100,000 in income, and pays the tax in a timely manner. The stock market goes down and by October 2016, her Roth IRA has decreased in value to $50,000. Carrie is disgusted and wants to strangle me for telling her how great it would be to make a Roth IRA conversion. Of course, she could stay the course and hope the investment will recover. Carrie does, however, have an even better course of action.

She should recharacterize (undo) the Roth IRA conversion by October 15, 2016. She would fill out the appropriate paper work with the IRA custodian to recharacterize the Roth IRA, returning it to a traditional IRA. After filling out the appropriate paperwork, she will have a $50,000 regular IRA instead of a $50,000 Roth IRA. Then, since she filed her tax return and paid the tax on the conversion, she should file an amended tax return, Form 1040-X, showing the necessary election is made under IRS regulations, and request a refund of the taxes she paid on the conversion. Or, if Carrie had filed an extension request on April 15, then she would not have to file an amended return at all—she would simply file her return, and disclose the transaction, but not pay tax on the conversion.

Granted, her investment is still $50,000 instead of $100,000, but even if she had not made the conversion, her investments would still be down in value. So, she is no better or worse off because she converted and recharacterized. If she then decides to convert another $50,000 after the 30 day waiting period, she would have the same value in a Roth IRA as she had before the recharacterization, but would only owe the IRS taxes on $50,000 of conversion income instead of on $100,000 of conversion income.

Over the years, our office has helped many clients recharacterize Roth conversions. The reason is that while we’re quite sure that Roth conversions are a great retirement and estate planning strategy for many, we have no way of knowing how the stock market will perform on any given day or any given year (or any time period for that matter). Many of our clients who have made conversions, often on my advice, were then advised to recharacterize or undo the conversion after the investment lost money. The clients who took my advice and reconverted the same accounts at the lower values to new Roth IRAs, recovered quickly from their initial annoyance and are now very, very happy. The tax consequences of their conversion were less, and the record growth that the market has experienced after 2008 has resulted in substantial tax-free gains in their Roth IRA accounts.

The fact that the tax laws allow you to recharacterize a Roth IRA offers some protection against making a Roth IRA conversion and experiencing a significant downturn in the investment in the short term. The ability to recharacterize might give additional confidence to IRA owners considering a conversion.

I do concede however, that if you make a Roth IRA conversion and the investment inside the account loses money over the long term or even becomes worthless, then the conversion will have been a mistake. That is one of the risks of doing a Roth IRA conversion.

Other risks involve congressional changes to the tax laws, as noted above. I confess to having some concerns about this. It is written into the Internal Revenue Code that Roth IRA conversions will stay income-tax free. True, they said the same thing about Social Security, and we are now paying tax on Social Security. The difference is that the Social Security provision was never part of the Internal Revenue Code. It was not taxed in the early years of the program because of a series of administrative rulings issued by the Treasury Department (which is not law), but in 1983, Congress made it law by specifically authorizing taxation of Social Security benefits.

If Steve Forbes got his way and the United States switched to a value-added tax or national sales tax and eliminated income tax, then the tax you paid on the conversion would presumably be wasted. Currently, though, there is over $7 trillion dollars in the IRA and retirement plan system and most taxpayers are expecting to pay taxes on that amount. And since the government really needs the revenue, I can’t see the taxes on IRAs and retirement plans being forgiven. What I think is more likely is a tax increase and, in that case, making a Roth IRA conversion while taxes are lower will yield even more benefits than my analysis shows.

At the time I am writing this, the market has returned to, and surpassed, the record highs it set before the financial crisis of 2008. Does this mean you should not make a Roth conversion unless the market goes down? Of course not! If you make a Roth IRA conversion and the market improves, you will be a happy camper. If it goes down, you can always do another conversion to a different Roth IRA and recharacterize the first one, allowing future gains to happen tax-free in the Roth.

After the first edition of Retire Secure! was published, I was invited to make presentations and train financial planners all over the country. One night, one of the financial planner attendees offered me a ride from my speaking engagement to my hotel. He told me that he read my book and talked to his parents about changing their wills and IRA beneficiary designations consistent with my recommendations. Even though both of his parents were in good health at the time, they listened to their son and changed their estate plan to the cascading beneficiary plan and made a series of large Roth IRA conversions. Unexpectedly, not long after making the recommended changes, his father died. In terms of benefits for the next generation, the planner conservatively valued the difference between the old plan and the new plan in millions of dollars. His “aha” moment was realizing that this advice works. But more important, he did something about it! If you think this advice is right for you, take action, preferably with the help of a qualified expert.

This chapter is not meant to be a complete analysis of all issues and strategies related to Roth conversions, but to give you some guidance on why this is potentially a great opportunity for you and your family. My book, The Roth Revolution, is devoted to the entire spectrum of opportunities within the Roth environment. In that book, I delve much deeper into the discussion of when and how to effectively capitalize on Roth conversions. So to learn more about these conversion opportunities, I recommend this book for further reading. If you would like more details on The Roth Revolution, please visit www.paytaxeslater.com.

A Key Lesson from This Chapter

A Roth IRA conversion can provide the Roth IRA owner and his or her family with an exceptional vehicle for increasing purchasing power.