O marvelous science, you keep alive the transient beauty of mortals and you have greater permanence than the works of nature, which continuously change over a period of time, leading remorselessly to old age. And, this science has the same relation to divine nature as its works have to the works of nature, and on this account is to be revered.

—Leonardo da Vinci

eonardo wrote entire tomes on how painting was a science, how music was “the younger sister of painting,” and how painting was superior to all other forms of art—poetry, music, and sculpture—as a medium for describing nature. He wrote that painting could capture a fleeting moment, the subject never aging beyond the time of execution of the subject’s likeness. Meanwhile, he seemed to take special delight in denigrating sculpture—an understandable prejudice, considering his greatest rival specialized in that medium: “Sculpture is not a science but a very mechanical art … generally accompanied by great sweat which mingles with dust and becomes converted into mud. His face becomes plastered and powered all over with marble dust, which makes him look like a baker.”1 In the hierarchy of intellectual pursuits, however, science maintained an unrivaled perch. Even as an apprentice, when he first took up a brush, Leonardo was already infusing his paintings with elements of his beloved nature, its secrets revealed by his unrelenting scientific inquiries. Thus his paintings are rich in anatomical, botanical, geological, and psychological overtones, and also rich in the geometric shapes and patterns, employed for either organizing his subjects or giving them depth and dynamism.

eonardo wrote entire tomes on how painting was a science, how music was “the younger sister of painting,” and how painting was superior to all other forms of art—poetry, music, and sculpture—as a medium for describing nature. He wrote that painting could capture a fleeting moment, the subject never aging beyond the time of execution of the subject’s likeness. Meanwhile, he seemed to take special delight in denigrating sculpture—an understandable prejudice, considering his greatest rival specialized in that medium: “Sculpture is not a science but a very mechanical art … generally accompanied by great sweat which mingles with dust and becomes converted into mud. His face becomes plastered and powered all over with marble dust, which makes him look like a baker.”1 In the hierarchy of intellectual pursuits, however, science maintained an unrivaled perch. Even as an apprentice, when he first took up a brush, Leonardo was already infusing his paintings with elements of his beloved nature, its secrets revealed by his unrelenting scientific inquiries. Thus his paintings are rich in anatomical, botanical, geological, and psychological overtones, and also rich in the geometric shapes and patterns, employed for either organizing his subjects or giving them depth and dynamism.

The shapes and patterns were extraordinarily enduring, recurring in his works again and again. As a teenager he painted a small section of Verrocchio’s Baptism of Christ. The contours and highlights of the curls in the angel’s hair are signature touches of Leonardo, reminiscent of the vortices in his drawings of the flooding Arno. The curls again appear in his Ginevra de’ Benci, executed when he was about twenty-one. A gentle helical twist imparts a sense of dynamism to the angel’s body in the Baptism of Christ; this is seen again in three of the four figures in the Virgin of the Rocks, painted when he was in his early thirties. Again, in the portrait Lady with the Ermine, created when Leonardo was in his late thirties, and in the Mona Lisa, painted when he was past fifty, the same helical contour imparts dynamism to the subjects.

Among paintings attributed to Leonardo’s first Florentine period is the unfinished painting Saint Jerome in the Wilderness (Vatican Museum). Jerome, who was identified so closely with nature, must have been a favorite of Leonardo’s, for his own psyche was inseparable from nature. In this early work depicting the old hermit, the figure of Jerome can be framed within a golden rectangle. Leonardo, who was later to illustrate Luca Pacioli’s De divina proportione, was of course intimately familiar with the divine proportion (and the golden rectangle), as well as with regular and semiregular polyhedral figures, which he depicted in rough sketches in his notebooks and presented formally in Pacioli’s book. Thus it was most likely more than a coincidence for Leonardo to frame the figure of Saint Jerome within a golden rectangle.

In order to dramatize the proportions of the kneeling figure of Saint Jerome, I have digitally superimposed the golden rectangle on the painting; then in the upper inset figure, reproduced a postcard with precisely the same proportions. The postcard I chose for the demonstration happens to bear the image of a classical Greek vase (crater) that fills the postcard precisely (Figure 9.1). The simple exercise of juxtaposing objects from different ages—from antiquity, the Italian Renaissance, and contemporary culture—in the same figure is meant to dramatize the timelessness of the golden rectangle, a shape more often than not chosen inadvertently but, by Leonardo, probably with careful premeditation.

In Milan Leonardo was a boarder in the house of the de’ Predis brothers, both painters. On April 25, 1483, he was commissioned to paint an Immaculate Conception altarpiece for a small church. The presumptuous officials dictated their own idea for a composition and even the choice of colors: “the cloak of Our Lady in the middle [is to] be of gold brocade and ultramarine blue … the gown … gold brocade and crimson lake, in oil … the lining of the cloak … gold brocade and green, in oil.… Also, the seraphim done in sgrafitto work.… Also God the Father [is] to have a cloak of gold brocade and ultramarine blue.”2

Indeed, the details of the colors and design required from Leonardo for this work continued another fourfold beyond those specified above. But Leonardo, after agreeing to the terms of the contract, went on to produce his own version. He organized the composition as a pyramid with the Madonna’s head at the vertex, her right arm draped over the infant Jesus, and her left hand poised to bless the infant John the Baptist. At the lower right corner is a kneeling angel pointing toward Jesus. Rugged stalactites and stalagmites, all immersed in a thick mist but punctuated by bright light, provide a surrealistic backdrop to the quartet of characters. The painting, known today as the Louvre’s famous Virgin of the Rocks (Plate 14), measures 198.1 by 122 centimeters, thus it has a height-to-width ratio of 1.62, or ϕ. Twenty years later, Leonardo, collaborating with his housemate Ambrogio de’ Predis, produced a variation of this painting for the church of San Francesco Grande in Milan. This painting, the London National Gallery’s Virgin of the Rocks, has overall proportions very close to its predecessor, but the backdrop of stalactites and stalagmites has been brought forward slightly, the Virgin and the two infants have halos, Jesus holds a scepterlike cross, and the angel is not pointing.

Figure 9.1. Leonardo da Vinci, Saint Jerome and the Lion (unfinished), 1482, Vatican Museum, Rome. (inset, top right) The image of an ancient Greek vase with the proportions of a postcard, the postcard itself in the shape of a golden rectangle.

In 1495 the forty-three year old Leonardo was commissioned to paint a mural in the dining room of the small church of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan—the theme, Christ’s last meal with his disciples. On the wall of the refectory for which it was planned, the natural light enters the room through windows on the left-hand side, and the work is appropriately customized for the setting. The right side of the scene is illuminated far more than the left, and the left sides of the individual figures are lit while the right sides are in gradations of shadow (see Plate 8). Artists of the Renaissance, in paintings depicting the Last Supper, would often separate Judas from the other disciples, placing him alone on one side of the table, separated from the rest of the disciples seated on the other. His full face was never presented, lest the viewer gaze inadvertently into the eye of evil. Leonardo has integrated Judas into one of four groupings of disciples, but made sure that his face is in shadow, and only one eye can be seen. In that moment, rife with electricity, when Christ has just made his announcement of the betrayal, Judas recoils in terror, knocking over the saltcellar.

Leonardo’s preliminary sketches reveal the intensity of the moment, the individual and group conflict, the psychological drama at that dinner table, in the faces and hands. Indeed, hands as much as faces represent a powerful instrument to convey passion. Verrocchio had already exposed his pupils to the emotive power of gesture in his figures. But Leonardo informed his Last Supper with much greater artistic currency than could his master—he had deeper insight into psychology, superior skills with his medium and composition. And as admonishment meant for young artists, he identified in the Libro di pittura pitfalls to avoid in multiple subject works: “Do not repeat the same movements in the same figure, be it their limbs, hands, or fingers. Nor should the same pose be repeated in one narrative composition.”

Leonardo, characteristically running late in completing the work, was called to task by a prior: “Why is it taking so long?” Leonardo responded that he was having a difficult time finding a model for Judas, and suggested to the prior that perhaps he might serve in this capacity. The prior departed, foaming with indignation, but refrained from further badgering the artist. In the mode of a modern director seeking just the right actor for his cast, Leonardo spent months observing, sketching, searching for just the right countenance he envisioned for each disciple. The casting for the model of Jesus Christ was evidently not unusually difficult. He found Jesus in a handsome and muscular young man, exuding confidence and an unmistakable air of piety. Several years later, Leonardo lore has it, he found his Judas in a Roman prison. From a close friend, who had also been on the lookout for the Judas character, he heard the description he was after. When he personally visited the prison and saw the bedraggled convict brought out for his viewing, Leonardo accepted the man without hesitation—only to find, to his shock and horror, that this broken wretch was the very man who had served as his Jesus!

When Leonardo finally finished the Last Supper, the mural was revolutionary in its composition, grouping the apostles in four groups of three, and isolating Christ. In this, the most dramatic of all of his paintings, Leonardo had captured that instant when Christ had just announced to the bewildered and distraught guests at dinner table, “Verily, verily one of you will betray me.” That moment of despair is said to reflect in Jesus’ face Leonardo’s own feeling of betrayal twenty years earlier in Florence.

Normally in painting a fresco, water-based paints are applied to wet plaster, thus penetrating and becoming a part of the plaster. Leonardo used oil-based paint along with varnish, and these, applied to a dry wall, never achieved sufficient penetration. Unproven techniques and materials, coupled with the salts leeching from the upwelling groundwater, caused the paint to gradually flake off. Over the centuries a number of attempts were made to restore the great mural, most of them expediting its decay. The most recent effort to restore the mural, a project that lasted seventeen years, may have finally succeeded in decelerating further degradation. Removal of almost all of the past restorers’ over-paint also revealed Leonardo’s original vivid palette.

Among the legion of artists who have tried to copy or produce variations of Leonardo’s Last Supper was Raphael Morghen, who produced arguably the best engraving based on the work (c. 1800) and served to disseminate the image. It is this engraving that reveals some of the details of Leonardo’s symbolism. Among the group immediately to the left of Christ is Judas, face in shadow and clutching a sack of silver in one hand (see Plate 7, bottom right).

Just as Leonardo was about to leave Urbino after three disappointing years in the employ of Cesare Borgia, Machiavelli helped him to secure a commission from the city of Florence. He and Michelangelo were each to paint on facing walls of the Great Council hall of the Palazzo del Signoria (now the Palazzo Vecchio) massive murals celebrating a pair of successful military campaigns carried out by Florence. Leonardo was to depict the Battle of Anghiari, which led to the defeat of Milan in 1440; Michelangelo, the Battle of Cascina, which led to the defeat of Pisa in 1364. Thoughts began to take shape in both artist’s notebooks, and each created full-size cartoons that were displayed and greatly admired. Sadly, just as the work commenced, Michelangelo was ordered to Rome to complete the tomb of Pope Julius II, and the commissions were withdrawn.

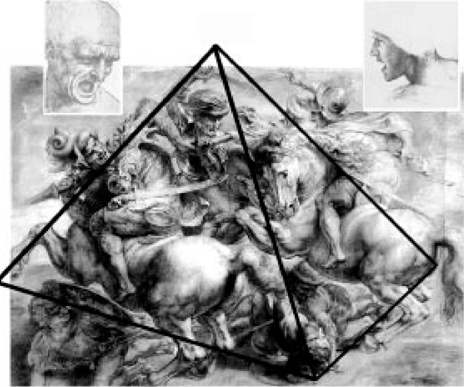

Leonardo had gone so far as to do an underpainting on the wall; it was covered by Vasari when he received a commission in 1563 to remodel the room. And although this cover-up was all too successful, defying even modern attempts to locate the unfinished mural using high-tech equipment, at least some of Leonardo’s sketches of battling warriors and horses can be found in his notebooks. Neither Michelangelo’s nor Leonardo’s cartoons have survived. Yet a hundred years after Leonardo first conceived its design, a copy of the cartoon, albeit by a poor artist, was still in existence. In 1603 the Flemish Baroque master Peter Paul Rubens replicated that cartoon in the “style of Leonardo.” In view of Rubens’s skill and his abiding reverence for Leonardo, it is likely that he reproduced as faithfully as possible what he thought Leonardo had in mind. If so, the cartoon reflects Leonardo’s personal aversion to the horrors of combat, notwithstanding his employment as a designer of engines of war. Some of Leonardo’s sketches of battling warriors and horses can be found in his notebooks; the faces are highly reminiscent of those of some of the warriors and horses in Rubens’s cartoon. As for the general shape and composition, the cartoon can be seen to invoke the golden pyramid to frame the subjects.

Figure 9.2. Peter Paul Rubens, drawing after Leonardo’s cartoon for the Battle of Anghiari (1603), Musée du Louvre, Paris; (insets, upper left and right) details of two sheets with studies of heads of soldiers for the Battle of Anghiari, both in the collection of the Szépmüvészeti Múzeum, Budapest

Therefore make the hair on the head play in the wind around youthful faces and gracefully adorn them with many cascades of curls.

—Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo painted only three portraits of women, approximately fifteen years apart, but each painting became a pivotal work in the history of art. In each instance he took a routine commission for a portrait of a woman of neither prepossessing beauty nor overwhelmingly lofty stature and bestowed immortality on his subject. These are the Ginevra de’ Benci, Cecilia Gallerani, and the Mona Lisa.

The only painting by Leonardo outside Europe is also his only known double-sided painting. It portrays Ginevra de’ Benci, the daughter of the wealthy Florentine banker Amerigo de’ Benci, on the obverse side, and a combination of symbolic flora on the reverse. In early 1474 Ginevra had married Luigi de Bernardo Nicolini, a prominent magistrate, and the portrait was created shortly thereafter. It is thought to have passed from the Benci family, which had died out by the early eighteenth century, into the hands of the princes of Liechtenstein, whose red wax family seal can be seen in the upper right corner of the reverse. In 1967 the National Gallery of Art in Washington acquired the painting from the Principality of Liechtenstein.3

Ginevra, with her hairline and eyebrows plucked to accentuate “a smoothly domed forehead” emblematic of her intellect, is seen in front of a juniper (ginepro) bush, a symbol of virtue and a play on her name. In the distance is a pair of church spires, presumably representing her piety. On the reverse juniper appears again—this time a sprig cupped by a laurel on one side and palm branch on the other. The relatively limited palette and the precisely delineated curls of her hair are evidence of the painting having been executed in the artist’s youth: he was just five years older than his sixteen-year old subject.

The painting is on a poplar panel, measuring 38.8 by 36.7 centimeters (15¼ by 14¼ in.); in other words, the overall shape of the portrait is virtually a square—or is it? When we carry out a simple geometric construction—inscribing the subject from the top of her head down to her bodice within a vertically configured golden rectangle, the head defining a square in the upper portion of the rectangle—we find that her chin rests almost directly on the lower edge of that square.

Painting the reverse side of the wooden panel had a salutary effect, for it has kept the panel perfectly flat for over five hundred years. Warping is caused by the cells on one side of a wooden panel absorbing more moisture than cells on the other (a less extreme case of the spiral pattern). This panel was hermetically sealed; however, even that cannot stop discoloration of the painting’s protective varnish, which yellows over the years. In 1992 the painting underwent thorough cleaning and restoration, and what emerged was even more beautiful than expected. Of course, the yellow filter of a varnish converts the blues to green and reds to orange. Removing the yellowed varnish from the portrait restored Leonardo’s original blue hues to the sky. It also revealed the rich undertones and overtones Leonardo used in painting the girl’s aristocratic complexion, much paler and more porcelain-like than had been evident. Women of the Renaissance were physically and figuratively sheltered, and suntanned skin was anything but fashionable.

The square shape of the Ginevra de’ Benci has long been a source of speculation, as this was a rare format for paintings in the Renaissance. Is there a missing part of the painting, and if so, what was there? Two of its edges, the right and the bottom, display evidence of damage and of having been sawed. We have also observed that for Leonardo the hands were as expressive as the face—that was the case in the Last Supper, and as we will see, that is the case with each of the three portraits. David Brown and National Gallery staff have digitally reassembled a study of hands by Leonardo (a drawing in Windsor Castle) and the portrait of Ginevra with remarkable results. The clue to how they should be aligned was on the reverse side, where the juniper twig was found to be offset by 1.3 centimeters in the direction of the damaged edge. Operating under the hypothesis that the juniper twig had been aligned at the center of the original panel, the first step was to add 1.3 centimeters to that, and then fill in the space digitally. The branches embracing the juniper were propagated downward to converge near the bottom of the panel. Then, on the obverse, the hands were digitally overlaid at the bottom of Ginevra’s image and manipulated—translated, rotated, and rescaled—until Brown achieved what he was convinced was the artist’s style and intent. But the digital colorization process leaves the colors of the hands and dress somewhat flat. Moreover, distinctly missing, especially in the hands, are the softness and grace with which Leonardo would have normally imbued his subject in an oil portrait. At least, however, we have an opportunity to see Ginevra’s position as it might have appeared in the original portrait (Plate 15, bottom left).

In 1482, eight years after he completed the Ginevra de’ Benci, Leonardo moved from Florence to Milan, having secured a post as court engineer for Duke Ludovico Sforza (Il Moro). Problems in civil and military engineering consumed his time, but frequent experimentation, studies in optics, sketches of mental inventions, and the systematic recording of results continued undeterred. On the infrequent occasions when he returned to painting, evidence of this intellectual ferment would be manifest in his art, and each new commission brought his work to a level of refinement far above the last. In 1491, when he painted the Lady with the Ermine (Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani), the cultivated mistress of Il Moro (Plate 15, center) fifteen years had passed since he had painted Ginevra de’ Benci, and there was an astonishing growth in sophistication. As in the Ginevra, this is a full-on portrait at a time when people were used to seeing only profiles of women, and it is rife with psychological overtones—the sideways glance, the delicate fingers. In fact, Leonardo’s Ginevra de’ Benci and Cecilia Gallerani were arguably the first psychological portraits ever seen.

On the painting of Cecilia Gallerani a golden rectangle is delineated, framing the area from the top of the head to the top of the bodice. A square is portioned off in the upper part of the rectangle, leaving a golden rectangle in the lower portion. The result is just as in the Ginevra de’ Benci.

In 1503, in Florence, Leonardo accepted another commission for a portrait—again after a fifteen-year hiatus from portrait painting—this time he was to paint the wife of the wealthy merchant Francesco del Giocondo. Indeed Leonardo had done very little other painting, having left a number of works unfinished. But his studies in everything else continued unabated, with notes recorded in two types of notebooks—one for daily observations and rough sketches and another for distillations of the best of the daily notebooks and more finished drawings. With the Ginevra de’ Benci, he had been a young artist just trying to get established, and Verrocchio may have passed on the commission to him. With the Cecilia Gallerani, the mistress of Ludovico Sforza, he probably just wanted to impress the duke. But with the wife of del Giocondo, it is a mystery why he even accepted the commission. We can speculate that perhaps he needed money. But one thing is certain: with the Mona Lisa, he produced a miraculous psychological portrait—spellbinding, hypnotic, timeless. You know this woman, and yet you don’t. She is looking directly at the viewer, but what is on her mind is the real enigma. She exudes confidence and uncertainty at the same time, with an expression that is both inviting and frightening. In a sense it is a universal statement about women, albeit by a man whose attitude toward the opposite sex was highly problematic. It is no wonder that her countenance and that partial smile have launched more wild speculations than all other works of art, among them: “She is pregnant,” “She is suffering from a tooth ache,” “It’s a self-portrait by Leonardo.”

After each fifteen-year hiatus from painting portraits, Leonardo returned with immensely greater knowledge and insight, and a more refined technique. This is not difficult to understand: it is quintessential Leonardo, his interests inseparable, all organic components of the same mind. Leonardo accepted the commission for the Mona Lisa in 1503 but did not complete it until 1507. For whatever reason—either because he had not completed it in a specified time or because he had become too fond of it and could not part with it—he never turned it over to Francesco del Giocondo. Leonardo left Florence with the painting in 1507 and kept it with him through his subsequent travels. He took the painting with him in 1516 when he moved to France, and it was still in his possession at his death in Amboise (south of Paris) in 1519. It was in Amboise that Francis I acquired the Mona Lisa for his local chateau. At different times afterward, the painting surfaced at three different locations: Fontainbleu, Paris, Versailles. At some point the painting found its way into the collection of Louis XIV, and after the Revolution it found a home in the Louvre, then Napoléon Bonapart commandeered the painting and hung it above his bed. Later, when Napoléon was sent into exile, the Mona Lisa returned to the Louvre, where it has been ever since.

In its five-hundred-year history the Mona Lisa has survived appalling ordeals. According to Leonardo scholars, at an undetermined time in the past a pair of columns framing the subject on a terrace were cut out. Then early in 1911 the painting was stolen and taken to Florence, where it was kept hidden under a bed by an Italian nationalist. In 1956 it was damaged by a madman who threw acid on it, and again in the 1960s by another who slashed it. But let us hope all this traumatic experience is in the past. Majestically it hangs in the Louvre (as La Gioconda or La Joconde), restored, shielded by bulletproof glass, and since the 1980s protected by a law that prohibits all future travel abroad.

The proportions of the Mona Lisa panel are about 1:1.45, not particularly close to the golden ratio of 1:1.618, though the earlier trimming of the painting on its sides makes this test meaningless for us. When the columns were still present and the painting was wider, its length-to-width ratio would have been smaller than 1:1.45. Other interesting geometric constructions, however, can be seen (Plate 15, lower right). As in the Ginevra de’ Benci and the Cecilia Gallerani, we first construct a golden rectangle enclosing the area from the top of her head down to the top of her bodice. A square delineated in the upper portion of the rectangle leaves her chin resting on the bottom edge of the square and her left, or “leading,” eye located at the center of the square. This was also true for the Ginevra de’ Benci and the Cecilia Gallerani, although in those paintings it was the right eye. Finally, the torso of the Mona Lisa—slightly turned, her right shoulder and her right cheek set back relative to the left shoulder and left cheek, respectively—can be inscribed in a golden triangle (with angles 72°—36°—72°). There is a question that begs an answer: Was this all a coincidence for Leonardo—just a manifestation of his unerring eye, as it most likely had been for the architects of the pyramids—or was it a conscious exercise? In the work of any other artist, we would assume these manifestations to be coincidental. For Leonardo, who seamlessly integrated mathematics, science, and art, and spent his life seeking unifying principles, perhaps not!

When Leonardo painted his earlier works of art such as the Adoration of the Magi and the Annunciation, the theory of one-point perspective had already been known for fifty years, and Leonardo had mastered it. By the time he painted the Mona Lisa, Leonardo had already learned how to manipulate it in order to produce special effects. For a painting’s image to be “lifelike” in the Renaissance meant the conveying of a feeling of being alive, rather than rendering an exact physiognomic or photographic likeness of the subject. Indeed, since no other images of del Giocondo’s wife exist, no one knows how she really looked. But from the canvas she is ready to speak: the outer edges of her eyes (the lateral canthus) have been painted purposefully blurred, creating a sense of ambiguity. Moreover, the landscape forming the backdrop behind her is higher on one side than on the other. Therein lies Leonardo’s trick: his artifice causes the observer’s eye to inadvertently oscillate back and forth across the subject’s eyes, creating an optical illusion of animation.

In the last chapter we examined Christopher Tyler’s serendipitous discovery of the central-line phenomenon, his observation that in a preponderance of single-subject portraits the vertically bisecting line of the canvas passed very close to one eye, whether the leading eye or the trailing eye. In one element of the matrix of portraits reproduced from Christopher Tyler was the portrait of Mona Lisa. Here we apply the center-line principle to the other two Leonardo portraits of women, the Ginevra de’ Benci and the Lady with the Ermine (Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani). The center line in the Ginevra has been drawn to bisect the existing panel and not the corrected version extended on the right by 1.3 centimeters, following David Brown’s reconstruction (the discrepancy in the position of the line is a negligibly small 2 percent). The center line is seen to pass convincingly close to the leading eye—the right eye for the Ginevra de’ Benci and Cecilia Gallerani and the left eye for the Mona Lisa. The left-cheek bias in Renaissance portraits pointed out by Nicholls is evident in the Mona Lisa, but not so in the Ginevra de’ Benci and the Cecilia Gallerani. But then three portraits are just too small a sample on which to make a sweeping generalization.

As the United States began to prepare for the five hundredth anniversary of the discovery of America in 1992, many museums around the nation launched programs to commemorate the event with exhibitions of their own. The National Gallery of Art, custodian of the Ginevra de’ Benci, planned Circa 1492, an exhibition of works from the era of Columbus, with aspirations of including Leonardo’s Lady with the Ermine, painted in 1491. The curators of Poland’s national Czartoryski Collection in Krakow were extremely reluctant to lend the priceless work, without a doubt the most important artistic treasure of the nation. The argument they offered was that the painting was too fragile. At that juncture, President George H. W. Bush appealed directly to President Lech Walesa, who was not entirely unreceptive to the idea. In expressing conditional agreement, he was conveying the tacit gratitude of Poland for American support in the struggle to break off from the Soviet Block.

Conservator David Bull of the National Gallery of Art went to Krakow to ascertain whether the painting was sound enough to travel. He examined the painting with a magnifying glass for four hours. To the stunned Polish curators’ delight, he pointed to one area and pronounced “there is Leonardo’s fingerprint,”4 something that no one had ever noticed. This discovery, and the assessment that the Lady with the Ermine was in condition to travel, helped the negotiations proceed to a successful conclusion. Four months later the painting was transported to the United States for a three-month visit amidst unprecedented security. Cecilia, accompanied by David Bull and two Polish curators, flew first class on a Pan Am flight to Washington, D.C. In the agreement that brought the work to the United States, it was also decided that after the three-month exhibition of the painting, David Bull could spend another week examining the painting with high-tech equipment in the National Gallery’s conservation laboratory. There on his Formica table, side-by-side he had the “two girls.” Bull had spent his professional life examining, cleaning and restoring masterworks by Bellini, Titian, Raphael, Rembrandt, van Gogh, Cézanne, Manet, Monet, and Picasso, “But two Leonardos at once …! In the rarefied world of art masterpieces such a moment is without compare.”5 The FBI was called in to photograph the fingerprints on both the Ginevra de’ Benci and the Lady with the Ermine using a specialized camera. The fingerprint images are stored—along with those of distinguished and notorious individuals of twentieth century—in the data banks of that institution.

In his investigations of the two portraits by Leonardo Bull relied mainly on the two basic techniques of x-radiography and infrared reflectography, along with the nowadays more common tool of the stereoscopic microscope. With x-radiography, x-rays are used to probe deep into the paintings with a view toward ascertaining the beginnings and the structure of the work. In the Ginevra de’ Benci, the images on the two sides of the panel are compressed, as both sides are visible simultaneously. This technique also reveals overpainting on previous images. On the reverse side of the Ginevra, underlying the Benci family motto “Beauty adorns Virtue” is another, “Virtue and Honor” (the motif of Bernardo Bimbo, who was Ginevra’s platonic lover and perhaps the person who commissioned Leonardo to do the painting). Thus Ginevra’s own motto was overpainted. On the Lady with the Ermine, x-radiography revealed that Leonardo had experimented with Cecilia Gallerani’s hands, altering their position after initially painting them.

David Bull found that infrared reflectography was most helpful for his needs when investigating the two portraits. This technology utilizes infrared radiation, which is much less penetrating than x-rays, to investigate the surface (and just below the surface) of paint. The infrared radiation reflects off the white gesso ground that lies between panel and paint, and the image is recorded by camera and made visible on a computer monitor. Bull’s examination of the two paintings with infrared reflectography revealed an underlying drawing outlining the subject. With his sitter before him, Leonardo would make a drawing on paper. He would take the drawing back to the studio and make pin pricks outlining the drawing, carefully going around the nose, the eyes, the lips. Then he would take the drawing with the holes punched through, essentially now a stencil, and lay it down on the gesso, then lightly dab the perforated study with a muslin bag of charcoal dust to transfer his design. The resulting outline of the figure was visible again in the infrared reflectography.

The Ginevra de’ Benci and the Mona Lisa, painted thirty years apart, each have pastoral background landscapes; and their astonishing chiaroscuro and sfumato keep them in perfect harmony with the subject. Chiaroscuro is a technique of painting in which the figures portrayed have somewhat nebulous outlines, seen emerging into the light from shadows. With sfumato, believed to have been invented by Verrocchio, the objects in a picture are coated with layers of very thin paint to soften edges and blur shadows, creating a dreamlike effect of atmospheric mist or haze. Leonardo had already exhibited his mastery of these techniques in the Virgin of the Rocks (1483).

The study of the Lady with the Ermine revealed another dramatic surprise. Painted midway in that thirty year span, it features a flat (albeit dramatic) black background that is out of character with the other two portraits. Art historians had long suspected that the original background had been painted over sometime in the past. Bull’s infrared reflectography studies revealed the background indeed had been altered, he speculates, in the nineteenth century. The obvious guess would be that the painting had once had a symbolic landscape similar to the other two, but Bull’s examination revealed none. It was a subtle iridescent blue-gray, somewhat evocative of the metallic paint one encounters on some cars, unusual for the Renaissance and unusual even for Leonardo. But then every innovation this man introduced broke new ground and left the medium much richer.

For both his works of art and scientific investigations, Leonardo personally developed and practiced a technique that is evocative of modern scientific methodology: careful experimentation, meticulous observation, copious recording of data, and a synthesis in the form of an explanation—a theory. But he did not publish! It is clear from the notes he left behind, however, that he approached everything with consummate open-mindedness. His art, whether religious or secular, was informed by the fruits of his scientific investigations—linear perspective, mathematics, optics, mechanics, anatomy, geology, even psychology. His subjects are depicted not just as photographic likenesses, but integrated into a canvas teeming with psychological overtones. In single-subject paintings they communicate with the viewer, and in multiple-subject paintings, also with each other.

Inquiry in any human endeavor, scientific or artistic, cannot proceed without experimentation, but experiments can go awry. Once Leonardo painted with oils onto a stone wall; then he applied heat to the wall in order to fix the paint. The paint melted and the creation was destroyed.6 A more serious failed experiment occurred on the Last Supper, where instead of simply using a proven mural technique, he introduced a method that was not conducive to the environmental conditions of the room and building, and the great mural began its inexorable deterioration process by the time it was finished.

Finally, there is one other Leonardo work that we must revisit—The Adoration of the Magi, long regarded as one of the gems of the Uffizi, hanging on an honored wall in the great museum. Although an unfinished work, the Adoration shows the perspectival studies made by Leonardo to be a prelude to a final painting. In spring 2002 a tragic discovery was made when the work was moved for restoration and conservation into the museum’s laboratory. A painstaking scientific analysis revealed to everyone’s horror that, although the underdrawing is indeed by Leonardo, the work was overpainted—possibly a century later—by an artist of modest talent. The museum staff subsequently took a sad but necessary decision, moving the painting not back onto its lofty perch in the museum, but into a storeroom where it has remained since. Perhaps the overpainting will be removed in the near future and the work can be exhibited as a Leonardo.

The high technology applied to Leonardo’s paintings has been revealing. Issues of color, composition, technique and especially provenance all make more sense. They eliminate wild speculation and guesswork, anathema to Leonardo. Moreover, since it had been the Renaissance artist who first taught the scientist to make careful observations, and ultimately to help launch modern science, we might regard high technology as a return favor by the scientist. The plethora of modern technical tools routinely resolve questions that in another age would have been accepted or rejected according to one’s intellectual prejudices. Among questions resolved by carbon-14 testing has been the authenticity of the Shroud of Turin (it turns out to be less than a thousand years old). High tech medical imaging—computer-assisted tomography (CAT-scan) and MRI—has been performed on Egyptian mummies, determining, among other things, the diseases to which various pharaohs ultimately succumbed. Cosmic radiation was employed in searching for hidden chambers, and ultimately mapping out the internal structure of the Chephren Pyramid (there were no hidden chambers).7 Radiography, with highly penetrating gamma radiation, was used in revealing an anachronistic internal wire structure in a Greek statue of a horse—a forgery! Among unresolved questions is the date of the occipital bone and right arm purportedly belonging to John the Baptist. (The Byzantine emperor Justinian with virtually unlimited resources had acquired them in the sixth century, a time when he was transforming Constantinople into an unmatched Christian reliquary.) The bones displayed now in the Topkapi Museum, Istanbul, have not yet been tested. The seedy side of the art and artifact business would be far more active than it is if some of the high tech tools did not exist to discourage the practice.

I offer an example of how the technology—even in its relative infancy almost sixty years ago—exposed an astonishing hoax. The story resonates with ironies, the artist claiming the forgery, the skeptical authorities rejecting his claims. Han van Meegeren, prewar Dutch artist of not entirely inconsequential talents, was far more creative as forger than as artist. Van Meegeren produced a number of “authentic” Vermeers, including works from hitherto unknown periods of the artist’s life. His recipe—mixing paint scraped from old paintings, painting over period paintings of little value, cooking and causing crackling—produced works of sufficiently convincing quality to fool most art experts.

After the war Meegeren was arrested, not for producing forgeries, but for trafficking with the enemy. While on trial for selling national treasures to the Nazis, specifically to Reich Marshal Hermann Göring, he was forced to admit the works were all of his own creation. Asking to have the paintings x-rayed, van Meegeren first revealed details of the underlying paintings. To buttress the claim, he set up an easel in front of six witnesses and an armed guard, and produced a ninth and final pseudo-Vermeer. Van Meegeren even claimed the highly acclaimed “Vermeer” Christ with His Disciples at Emmaus, which had found an honored spot in the Rotterdam Museum, to be his work. The definitive test of provenance for this work had to await the development two decades later of sophisticated new radioisotope technology. The determination of the precise ratio in the paint of the radioactive isotopes Ra-226 and Pb-210 revealed the painting to have been created in the twentieth century and not in the seventeenth.

Poetic justice and irony abound in the van Meegeren–Vermeer case. First, van Meegeren, who had planned and toiled to produce work that would fool the critics, had to turn around and convince them of his forgery. Second, the same critics who had panned van Meegeren for lack of talent, accepted the works by van Meegeren as authentic Vermeers, uncontestable creations of genius. Third, absolved of charges of treason, van Meegeren was convicted of forging Vermeer’s signature. Fourth, despite the conviction, van Meegeren became a national hero as, “the man who had duped Göring.” Fifth, just before beginning his term, a one-year sentence, van Meegeren had a heart attack and died. Finally, the ultimate irony emerged: the purchaser, Göring, had paid for the paintings with counterfeit money.