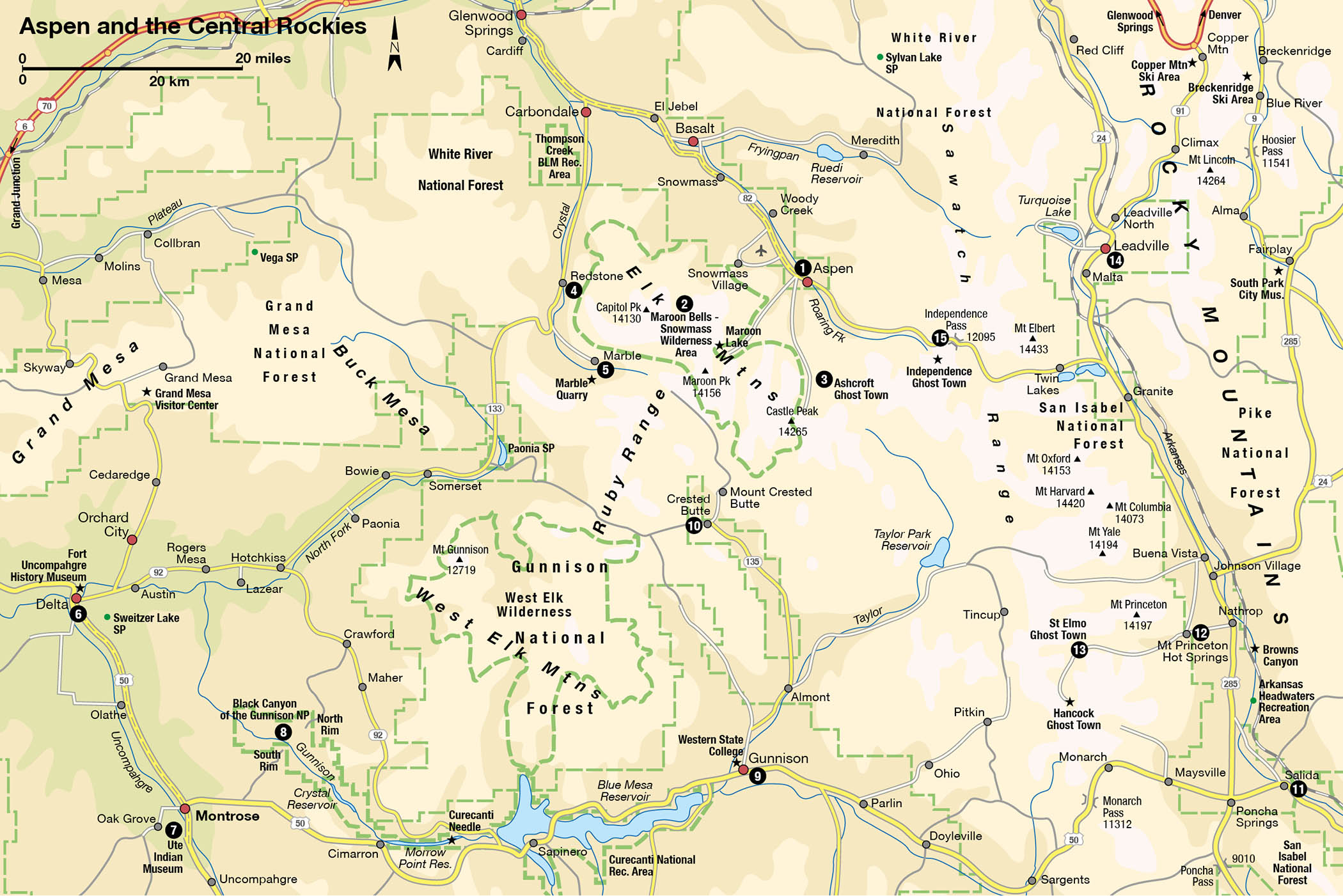

Although Aspen 1 [map] and Crested Butte are only 25 miles (41km) apart, the terrain in between is impassable to cars, requiring a drive of more than 200 miles (320km). This chapter combines two possible highway routes between the towns into a 450-mile (725km) loop tour. En route lie the deepest canyon, the highest mountain, and the largest lake in Colorado. You will also discover a 19th-century miners’ utopia, the place where the marble for the Lincoln Memorial was quarried, some of the state’s best-preserved ghost towns, and a historic hot springs resort.

Freestyle skiing in Aspen.

Getty Images

Heading to the slopes, Aspen.

AWL Images

As the central hub of the Rockies, the loop tour can be divided into segments that connect many other scenic routes, most notably Interstate 70 (for more information, click here), the San Juan Skyway (for more information, click here) and the San Luis Valley (for more information, click here). Whichever destinations you pick, your trip will take you through the heart of the Rockies.

The richest town in the Rockies

“This place is getting to be like Aspen,” locals say in revived Victorian towns throughout the Rockies whenever a new bed-and-breakfast, café, or art gallery opens – and they don’t mean it in a good way. Yet, secretly, many small-towners would love to see their communities become “the next Aspen” – if only they could still afford to live there. Aspen is the prototype for every other former ghost-town-turned-tourist-resort.

In the silver boom of the 1880s, Aspen grew into a town of 12,000 people. Then, following the silver crash of 1893, it faded away until its population numbered just 350 and its brick buildings stood empty or collapsed. Gingerbread mansions with smashed windows could be bought up for a few hundred dollars in back taxes, if anybody had wanted to own them. Aspen survived only because it was the seat of Pitkin County, which otherwise consisted entirely of national forest land.

Then, after World War II, something happened in Aspen that nobody could have predicted: Friedl Pfeifer, an Austrian ski instructor, announced plans to build Colorado’s first ski resort. The idea was, of course, absurd. Few Americans skied and, before I-70 was built, Aspen itself was in one of the most remote places imaginable. Yet Pfeifer, with financial backing from Chicago cardboard box tycoon Walter Paepke, succeeded in building his ski slope, and in 1950 it was selected as the site of the World Alpine Ski Championships. In 1960, the first televised Winter Olympics introduced many Americans to the sport, and within five years the number of skiers in the US grew by a phenomenal 850 percent. Aspen experienced a boom unrivaled even in the old mining days.

Summer fun

Pfeifer and Paepke also anticipated a problem that has confronted every other ski resort town since: what to do during the eight months of the year when there’s no snow. In 1950, the town garnered national attention with the Goethe Bicentennial Convocation, an alpine festival of philosophy and music, with Albert Schweitzer as keynote speaker – the only time he ever left Africa. Also featured were some of the nation’s leading classical musicians, including pianist Arthur Rubinstein and the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra. Though the Goethe connection was dropped the next year, the festival inspired the Aspen Institute, the Aspen Music Festival, and the Aspen Design Summit, all of which continue to this day. Other prestigious summer celebrations have been added, including two jazz festivals and one of the largest dance festivals in the United States.

Aspen ambience

Aspen is not really about sightseeing; it’s about ambience. After Twentieth Century Fox acquired the Aspen Skiing Company in 1978 (it’s now owned by the Crown family of Chicago), the town became Colorado’s answer to California’s Beverly Hills – a very expensive place where tourists are tolerated but outnumbered by the rich, famous, and absolutely fabulous. You can shop for a painting that costs more than an automobile or take in a ballet. Go to a nightclub where it’s hard to get in, then have sushi delivered to your suite at midnight. Learn to climb rock cliffs, ride whitewater in a kayak, or paraglide, but keep your eyes open for the beautiful people. Word has it that billionaires have purchased so many homes in Aspen that there are none left for mere millionaires.

Skiing down Ajax Mountain, Aspen.

iStock

Visitors today approach Aspen via CO 82 south from Glenwood Springs. The four-lane freeway up the Roaring Fork Valley runs between hillsides stacked high with multimillion-dollar homes and past the busy airport, its tarmac lined with Lear jets. Arriving at last in the compact, lavishly refurbished historic district, the place to start sightseeing is the Wheeler/Stallard Museum A [map] (620 W. Bleeker Street; tel: 970-925-3721; www.aspenhistory.org/tours-sites/wheeler-stallard-museum/; year round Tue–Sat 1–5pm, June 14–Sept 10:30am–4:30pm), a magnificent Victorian mansion in Queen Anne style built in 1888 by the founder of Macy’s department store in New York. Period furnishings and historical photographs recall Aspen’s history from the 1880s to the present day.

The museum is the starting point for guided and self-guided tours of the historic district. A highlight is beautifully restored Wheeler Opera House B [map] (320 E. Hyman Avenue; tel: 970-920-5770; www.wheeleroperahouse.com; Tues–Sat noon–6pm,; free guided tours), which offers a full schedule of performance events during the evening, and houses the town’s visitor information center. Other historic district sights include the Pitkin County Courthouse C [map] (506 E. Main Street; tel: 970-925-7635), with its solid silver dome, and the elegant old Hotel Jerome D [map] (330 E. Main Street; tel: 855-331-7213).

Aspen can feel very heady. To reconnect with your quieter natural self, head to one of the most scenic spots in the Rockies, photo-perfect Maroon Lake. The lake is located 10 miles (17km) south of Aspen at the end of Maroon Creek Road and mirrors the majestic Maroon Bells, twin 14,000ft (4,265-meter) peaks whose sheer, angular rock faces are stained red by iron oxide. A gentle trail leads around the lakeshore and past beaver ponds, and hikers can continue as far as Crater Lake at the base of the mountains.

Other trails lead deep into the Maroon Bells−Snowmass Wilderness 2 [map]. The only way to reach Maroon Lake is by taking one of the year-round Castle Ridge/Maroon shuttle buses, which leave every 20 minutes from the newly remodeled Rubey Park Transit Center in downtown Aspen (450 E. Durant Street; tel: 970-925-8484; www.rfta.com; daily 8am–5pm) for Aspen Highlands Ski Area; from there, you can pick up a Maroon Bells tour bus.

Another vantage on Aspen’s past awaits visitors to Ashcroft 3 [map], 12 miles (20km) south of town, on Castle Creek Road. Only nine empty buildings remain at the site, a ghostly remnant of a town that in its heyday was larger than Aspen. Friedl Pfeifer originally planned to build his ski area at Ashcroft, which might have changed its fate.

A few cabins are all that remain of Independence, a former gold-mining camp outside Aspen, founded in 1879 and abandoned in 1899.

Dreamstime

Redstone, coal, and marble

Thirty miles (48km) north of Aspen on CO 82, CO 133 branches off to the left at Carbondale for the start of the 205-mile (330km) West Elk Loop Scenic and Historic Byway, a lasso-shaped backroute around the spectacular West Elk Mountains and the lush North Fork Valley.

The road meanders 17 miles (27km) southwest along the peaceful two-lane highway to Redstone 4 [map], a hideaway town. It got its start in the 1880s as a company town for a coal mine owned by industrial visionary John Cleveland Osgood. Believing that a better living environment would make laborers more productive, Osgood built 84 Swiss-style chalets for his married mine workers and a rambling inn for the bachelors—among the first homes in Colorado to have electricity and indoor plumbing.

Osgood’s own grandiose 42-room sandstone mansion, Cleveholm Manor (58 Redstone Boulevard; tel: 970-963-3463, tours Fri–Mon 1.30pm; charge), otherwise known as Redstone Castle, is at the end of the town’s main street. Eventually, Osgood lost his mining interests in a hostile takeover. The coal mine was closed down, the miners moved away, and Osgood and his new wife went into seclusion in their mansion in the otherwise abandoned village. Today, the town is still about the same size as it was in Osgood’s time and is inhabited mainly by artists and craftspeople who sell their creations in Aspen, Denver, or elsewhere. The bachelor miners’ lodge has been converted into the Redstone Inn (82 Redstone Boulevard; tel: 970-963-2526), a bed-and-breakfast.

Five miles (8km) up CO 133, a narrow paved road turns to the left and goes to the former ghost town of Marble 5 [map]. The town was founded as a marble quarry and mill, which produced blocks of snow-white stone used for massive public sculptures, including the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and the Lincoln Memorial. At the Old Mill Site, huge slabs and blocks of marble lie haphazardly scattered from before the mill closed down in 1942. The small Marble Museum (412 W. Main Street; tel: 970-963-9815; www.marblehistory.org; May–Sept Thu–Sun 11am–4pm, Oct–Apr Sat–Sun; free), exhibits vintage photographs and memorabilia in the town’s first high school, built in 1910.

Fact

The small farm town of Paonia was named after the Latin word for peony in 1882 by its founder Samuel Wade, who brought peony root stock with him to Colorado. Peonies still grow in the town park.

The artsy farm town of Paonia on the North Fork of the Gunnison River is the gateway to Delta County, one of the richest farming areas in Colorado. The area was once a broad floodplain where, during the spring run-off, walls of water gushed through the Black Canyon of the Gunnison, inundating the valley and enriching the soil. The flooding halted with the completion of Blue Mesa Reservoir on the river above the canyon. The North Fork Valley communities are gaining in popularity with outdoors lovers and creative people escaping the city to enjoy the idyllic pastoral setting at the base of the West Elk Mountains. The scenic byway continues through the valley, passing organic farms (each with its own farmstand selling cherries, peaches, and other produce); grass-fed cattle ranches; an artisan goat dairy; 11 wineries (many part of the West Elks Wine Trail food-and-wine event, held in August); and organic local foods cafes and bed-and-breakfasts.

CO 133 meets CO 92 at the crossroads hamlet of Hotchkiss. From here, West Elks Loop continues south on CO 92, passing through historic Crawford and its distinctive Needle Rock formation, a spectacular drive south to US 50, following the east side of Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park.

Where

The North Rim of Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park can only be reached via an unpaved road from tiny Crawford, south of Hotchkiss. Open seasonally, you’ll find a ranger station, a primitive campground, nature trails, and the park’s best birding.

If you turn right at Hotchkiss and drive 20 miles (32km) west on US 50, you reach homely Delta 6 [map], located at the confluence of the Uncompahgre and Gunnison rivers. Fort Uncompahgre Interpretive Center (440 Palmer Street; tel: 970-874-8349; June–Oct Tues–Sat 9am–4pm; charge) was once a rather disheveled 1990 replica of a trading post established in 1828 by fur trader Antoine Robidoux that became the first permanent settlement here. After renewed interest in the site, in 2015, it was reenvisioned and reopened as a living history museum. Self-guided tours take you through a Trapper’s Cabin, Horno, Cocina, Trade Room, Powder Magazine, Blacksmith’s Forge, and other pioneer exhibits manned by costumed interpreters offering demonstrations of frontier life. Entrance is through a visitor center/ bookstore, where you will find an information desk.

Montrose, 21 miles (34km) south of Delta on US 50, anchors the north end of the popular San Juan Skyway Scenic Byway. It is the nearest city to both Ouray and Telluride and the western gateway to the South Rim of Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park.

The top attraction in Montrose is the Ute Indian Museum 7 [map] (17253 Chipeta Road; tel: 970-249-3098; Tue–Sat 9am–4:30pm), known for its Ute artifacts and as a focal point of tribal celebrations on the West Slope. The museum sits on 8.65 acres (3.5 hectares) of land homesteaded by Ute Chief Ouray.

Chief Ouray was an impressive American Indian spokesman who led diplomatic missions to Washington, DC, and negotiated a government treaty that reserved the entire southwestern region of Colorado Territory for the Utes in 1873. He guided his people through the transition from nomadic hunting and trading to agriculture, becoming an excellent farmer himself. Visitors can view a poster-size photo of the signed treaty and learn how, eight years later, when gold was discovered in the San Juan Mountains, the federal government broke the treaty and relocated the Northern Ute tribe to a reservation in Utah. Adjoining the museum is Chief Ouray Memorial Park. Ouray’s beloved wife Chipeta is buried here; she is said to have started the colorful columbine gardens that still fringe the park’s broad lawn.

Chief Ouray was chief of the Uncompahgre Ute tribe. He is pictured here with his wife Chipeta.

Library of Congress

Edge of the abyss

Fifteen miles (24km) east of Montrose on US 50 is the turn-off for the South Rim of Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park 8 [map] (tel: 970-641-2337; www.nps.gov/blca; year-round). The South Rim has a modest visitor center, a 7-mile (11km) long scenic drive that leads to 12 overlooks, picnic areas, two year-round campgrounds (water May–Oct only), and a moderate rim trail suitable for all the family. There are no food outlets, lodging, or other services in the park.

The canyon itself couldn’t be more dramatic. It is more than twice as deep as it is wide, with dark-hued, vertical walls of 1.7-billion-year-old granite and schist dropping an average 2,000ft (610 meters) from the rim to the river below and narrowing to as little as 40ft (12 meters) wide at river level. Adventurous visitors can obtain free wilderness permits from the visitor center to make the strenuous hike to the bottom or do a whitewater rafting trip through it.

An overlook at Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

Upriver, virtually all of the canyon was flooded to make the three reservoirs in Curecanti National Recreation Area (tel: 970-641-2337; www.nps.gov/cure). Crystal Reservoir and Morrow Point Reservoir, both long, slender lakes that seem more like big, lazy rivers, are out of sight of the main highway, have no boat ramps, and are only open to kayaks, inflatables, and other hand-carried boats. You can’t miss Blue Mesa Reservoir, just west of Gunnison: US 50 follows its shoreline and crosses over it on a long bridge. Colorado’s largest lake, it attracts boaters, water-skiers, and windsurfers from all over the state. Its cold depths provide habitat for kokanee salmon and giant mackinaw trout. Camping, hiking, and information are available at Blue Mesa Point.

Mountain bike heaven

Nearby Gunnison 9 [map] is home to Western State Colorado University. With a student body of 2,400 and a total population of only 5,973, one would expect this college town to be livelier than it is. The economy focuses on outfitting fishermen, hunters, and horseback riders for expeditions into Gunnison National Forest, a 1.7-million-acre (690,000-hectare) expanse of evergreen woodlands and towering granite peaks that reaches north to the Maroon Bells. Long, rocky forest roads follow creeks up into the mountains and provide access to pack trails for the West Elk, Raggeds, and Maroon Bells−Snowmass wildernesses.

Black Canyon of the Gunnison is so named due to the extreme steepness of the canyon walls. It is difficult for light to penetrate to the bottom, and the rock walls often appear black in the daytime.

Nowitz Photography/Apa Publications

The paved route into the national forest, CO 135, begins as Main Street and winds north along the Gunnison River headwaters for 28 miles (46km) to Crested Butte ) [map], a former ghost town turned ski resort. The town’s location, surrounded by four 12,000ft-elevation (3,655-meter) peaks, makes for magnificent views at any time of year, and the midsummer wildflower displays on the mountain slopes are among the best in the Rockies. Unlike most other historic ski towns, the ski runs, chair-lifts, lodges, and a 252-room resort hotel at Crested Butte Ski Resort (www.skicb.com) are located 2.5 miles (4km) away in the modern village of Mount Crested Butte. Built in 1881 as a coal-mining town for the railroad that ran through Gunnison, historic Crested Butte was declared a National Historic District at the same time ski area development began, so no new construction is allowed in town. Refurbished and carefully preserved, it’s a town of eccentric little bed-and-breakfasts, bars, gourmet restaurants, and art galleries in old miners’ cabins and saloons.

Even more than for its skiing, Crested Butte is famed for mountain biking. Colorado’s most popular summer sport was invented here in the early 1970s by Neil Murdoch, a young hippie who adapted an old newspaper bike for riding on Jeep roads and trails. He organized the first “fat tire” bike races over the mountains between Crested Butte and Aspen and promoted them into Fat Tire Bike Week, the largest mountain bike event in America, which takes place each year in June. Then in 1999 federal officers showed up in Crested Butte with a warrant charging that Murdoch was a fugitive living under a false identity, wanted for failure to appear in court on a drug charge 25 years before. Murdoch, then in his fifties and a pillar of the community, eluded the officers and disappeared. His whereabouts are still unknown.

Mountain biking on the plateau near Fruita.

Colorado Tourism/Matt Inden

There are more than 50 designated mountain bike trails in and around Crested Butte. Bikes are for rent all over town in the same shops that rent skis in the winter; guided bike tours are also available.

Up the river

Back on the main highway, US 50 continues east for 61 miles (100km), climbing above timber line to cross the Continental Divide over 11,312ft (3,353-meter) Monarch Pass, with its small ski resort and its summertime aerial tram (tel: 719-530-5000; www.skimonarch.com; May–Sept daily 8.30am–5.30pm), before intersecting US 285 at the crossroads village of Poncha Springs. Drivers following the West Elks loop route back to Aspen will turn north here, but first, why not take a break and stroll around Salida, 5 miles (8km) farther east on US 50?

Monarch Pass in fall.

Dreamstime

According to the Colorado Historic Preservation Review, Salida ! [map] (est. pop. 5,467) has “the finest collection of historically significant buildings in the state.” The main street leads through a classic residential area with tidy lawns on its way downtown, where metal plaques identify 78 historic buildings, many of them beautifully restored and now serving as art galleries and excellent small restaurants and cafés serving local foods. Salida is increasingly becoming a hot art destination and affordable retirement town, but, like its neighbor Buena Vista, it’s best known as a jumping-off point for all kinds of outdoor activities, from mountain biking and climbing the nearby mountains to camping, hiking, and fishing.

In a category all by itself is the superb whitewater rafting and kayaking on the Arkansas River Headwaters Recreation Area (307 W. Sackett Avenue; tel: 719-539-7289; daily 8am–5pm). During the FIBArk Whitewater Festival in June, 10,000 people come to town to take part in the oldest, longest whitewater race in the world. The 150-mile (240km) long stretch of the Arkansas River that runs from above Buena Vista to Cañon City, below Salida, is the most heavily run whitewater river in the country. Depending on the year, 250,000 people or so run it in the two-month whitewater season. The rafting industry is worth $55 million to the local economy.

Returning to Poncha Springs and heading north on US 285, it’s 16 miles (26km) to the tiny village of Nathrop, the starting point for whitewater rafting trips through Browns Canyon, the only segment of the upper Arkansas River that does not run alongside a highway. In fact, the steep-walled canyon is only accessible by backroad at one point in its entire 10-mile (16km) length.

Directly across the highway from Nathrop, a road climbs to Mount Princeton Hot Springs @ [map] (15870 CR 162; tel: 719-395-2447; www.mtprinceton.com; year-round). The original spa resort dates to 1879, when a three-story hotel was built on the site by the wealthy owners of a nearby mine. The hotel’s fortunes waxed and waned over the years, and in 1950, it was disassembled for lumber and shipped to Texas to build a housing subdivision. The current resort was built in 1960. It has been completely renovated by new owners and now includes not only the lodge but new cabins by the river. The lap pool, soaking pool, and spa are open to the public and have a grand view of 14,197ft (4,327-meter) Mount Princeton.

Although the pavement ends at the hot springs, the road continues for 15 miles (25km) around the south face of Mount Princeton to St. Elmo £ [map], one of the best-preserved ghost towns in the state. Established in 1878, the old mining camp grew into a town of 2,000 people before its mineral wealth ran out and it was abandoned. As of the 2010 census, it had a population of eight. More than two dozen weathered wooden buildings are still standing, including a saloon, the old county courthouse and jail, the church, and an unusual two-story outhouse, as well as a General Store (tel: 719-395-2117; www.st-elmo.org; open daily May–Oct 9am–5pm). Mount Princeton is part of a mountain range known as the Collegiate Peaks. Motorists driving north on US 285 will also pass Mount Yale, Mount Columbia, Mount Harvard, and Mount Oxford, all over 14,000ft (4,270 meters) tall. Mount Harvard and Mount Yale were named in 1869 by a professor who escorted a group of Ivy League geology students to Colorado and climbed the 9 peaks. The others were named by members of the Colorado Mountain Club after their alma maters.

Shop

Buena Vista is home to Jumpin’ Good Goat Dairy (31700 Highway 24 N; tel: 719-395-4646; www.jumpingoodgoats.com; open Apr–Oct Mon–Sat 10:30am–5pm, call for off-season hours; summer tours 11:30am Wed, Fri, Sat), where Dawn Jump creates 40 different varieties of cave-aged farmstead goat cheese from the milk of her 178-goat herd.

At the foot of the range is Buena Vista, an unremarkable town of 2,736 that is the main commercial center for South Park, a bowl of grasslands and hills that stretches between the Collegiates and the west face of Pikes Peak. The large facility on the southern outskirts of town is the Colorado State Reformatory, Buena Vista’s largest employer.

Twenty-two miles (35km) north of Buena Vista at Twin Lakes, a cluster of lodges and cabins near the shores of two reservoirs, CO 82 turns off and climbs over the Continental Divide for the return trip to Aspen. Before taking it, though, sightseers will want to detour another 15 miles (24km) north to Leadville, a famous mining town as different from Aspen as can be.

At an elevation of 10,152ft (3,094 meters), Leadville $ [map] claims the distinction of being the highest town in the United States. It got a fitful start during the “Pikes Peak or Bust!” gold rush of 1859, but it was not until major deposits of gold and silver were discovered there 20 years later that its population exploded from 1,200 to 45,000 almost overnight, making it one of the largest cities in the state. Though it deflated just as quickly when silver prices collapsed in 1893, large-scale mining continued at the nearby Climax Molybdenum Mine until 1980. Today, a large percentage of the town’s 2,580 residents ride the daily workers’ shuttle to hotel jobs in Vail, 37 miles (60km) away on the other side of the Continental Divide.

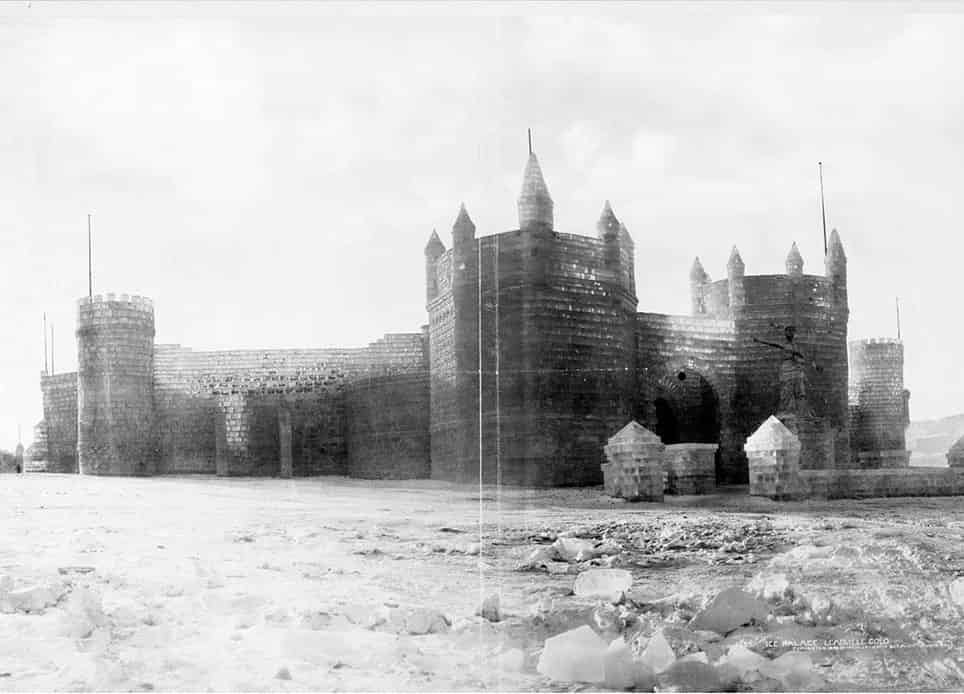

Leadville Ice Palace in 1876.

Library of Congress

Leadville has its share of scenic beauty, as walkers, bikers, and joggers can see for themselves along the paved 12.5-mile (20km) Mineral Belt Trail, which loops around the outskirts of town. There’s camping and a full range of water sports (but no marina) at nearby Turquoise Lake, a large reservoir with a wooded shoreline. But Leadville’s main attraction is its history. This is the town where some of Colorado’s most famous historical figures struck it rich — figures like Horace Tabor and his two wives, Augusta and Baby Doe, and J.J. Brown and his “unsinkable” wife, Molly (for more information, click here).

The best introduction to the town’s colorful past is the Leadville Heritage Museum (102 E. 9th Street; tel: 719-486-1878; May–Aug 10am–5pm, by appointment rest of the year). In addition to memorabilia from the gold and silver days, the museum features an exhibit about the US Army’s 10th Mountain Division, whose soldiers on skis trained in the surrounding mountains before and during World War II. The founders of the ski resorts at both Aspen and Vail first came to the region as part of the division and returned after the war.

Leadville’s frozen asset

In 1876, following the silver bust three years earlier, boosters in Leadville decided to recruit unemployed miners to build the world’s largest ice palace. Five thousand tons of ice blocks were hoisted onto a timber framework, then sprayed with boiling water to seal them together, creating an ice palace covering 5 acres (2 hectares) and reaching 90ft (27 meters) tall, with twin towers and an enormous arched doorway. Inside, glittering in the glow of electric lights, were a restaurant, an ice rink, a dance pavilion, a carousel, a casino, and toboggan runs. Admission was 50¢ and, although sold out regularly, the ice palace was a financial disaster and was never repeated. A model of the palace is on display in the Leadville Heritage Museum.

Another peek at local history awaits just up the street in the Healy House (912 Harrison Avenue; tel: 719-486-0487; May–Oct daily 10am–4.30pm), a gingerbread mansion built for a mining engineer. Guides in Victorian-era costumes show visitors through the period-furnished rooms. Behind the Healy House, and included on the same ticket, is Dexter Cabin, built of logs by a prospector who later became one of the district’s first millionaires and converted it into a gentlemen’s poker club.

The National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum (120 W. 9th Street; tel: 719-486-1229; www.mininghalloffame.org; daily May–Oct 9am–5pm), dubbed “the Smithsonian of the Rockies,” traces the history of hard-rock mining from the gold rush days to the present. Mining equipment, models, ore samples, and fluorescent minerals are on display, along with exhibits about pioneer miners and prospectors.

Although Horace Tabor, Leadville’s famed silver tycoon, is not remembered for his philanthropy as other mining millionaires like Molly Brown and Winfield Scott Stratton are, he did make public contributions in the form of opera houses in several of the region’s larger towns. In his home town of Leadville, it was the Tabor Opera House (308 Harrison Avenue; tel: 719-486-8409; www.taboroperahouse.net; May–Sept Mon–Sat 10am–5pm, tours most days noon–6pm). When it was built in 1879, it was said to be the finest theater between St. Louis and San Francisco, and the opera house today remains a symbol of a bygone era. In 2015, it was sold to the city of Leadville, which aims to restore the dilapidated theater with help from donations and grants. In 2016, the opera house was listed as one of Colorado’s Most Endangered Places, a Colorado Preservation, Inc. program to raise awareness about Colorado’s most endangered landmarks and fund restoration. In the meantime, the theater hosts a full roster of summer concerts on the stage where Oscar Wilde, John Phillip Sousa, and the Metropolitan Opera Company appeared – and Harry Houdini disappeared. (The trap door he used still works.)

Tabor Opera House Museum.

Dreamstime

Leadville’s must-see attraction, the Matchless Mine Cabin (E. 7th Street; tel: 719-486-3900; daily 9am–4.45pm), may not be much to look at, but it fairly crackles with history. This was the site where grocer and town mayor Horace Tabor made the rich silver strike that made him one of the wealthiest men in Colorado – until the crash in silver prices following the repeal of the Sherman Silver Act in 1893 left him a pauper. He was working in a Denver post office when he passed away. Legend has it that his dying words to his second wife, Baby Doe, were “Hold onto the Matchless as it will pay millions again.” Although in fact the Matchless had already been foreclosed by creditors.

Visitors who are intrigued by Baby Doe’s story can see her depicted in a one-woman show performed on summer evenings at the Healy House.

Baby Doe Tabor.

Denver Public Library, Western History Collection

Independence Pass

Returning south to Twin Lakes, motorists who turn onto CO 82 (closed in winter) find themselves headed directly toward a wall of peaks that appears impassable. The road scales the near-vertical granite face by switchbacks to 12,095ft (3,686 meter) Independence Pass % [map], the highest mountain pass in the United States that can be reached by paved road. At the summit, a trail leads across alpine tundra strewn in summer with thousands of tiny wildflowers, to an overlook from which on a clear day you can see at least 18 “fourteeners” – peaks that stand more than 14,000ft (4,270 meters) above sea level.

At the center of this breathtaking panorama, toward the southwest, you can pick out the easily recognizable shapes of the Maroon Bells, at the heart of the wilderness that lies between Aspen and Crested Butte. On the other side of the highway stands the summit of Mount Elbert, at 14,433ft (4,400 meters) the highest mountain in Colorado. The fact that it doesn’t look all that big emphasizes how high the pass summit is. From here, CO 82 makes a somewhat more gradual descent into Aspen, completing this grand tour of the central Colorado Rockies.

View from Independence Pass.

Robert Harding