Prune to keep the vine to a manageable size.

Prune to keep the vine to a manageable size.Much of your family’s best winter eating can come from the berry patch. Each year you can stock your freezer with raspberries, blueberries, currants, gooseberries, and elderberries. By late fall, jars of preserves and colorful juices will line your pantry shelves, ready to eat through winter. These small fruits come in many hues, flavors, shapes, and sizes. There are red, pink, and green varieties of gooseberries; black, purple, red, and pink raspberries; and many different grapes, blueberries, blackberries, and currants.

Bush fruits, brambles, and grapes are tasty, full of vita-mins, and easy to grow. They are productive — most bear a year or two after planting. The plants are usually inexpensive, need surprisingly little care, and take up very little room in the garden.

Prune bush fruits for the same reasons you prune fruit trees. Proper pruning extends the useful life of a berry patch by many years. Prune your grapes and berries well, and you will help them resist disease, produce larger fruit and better crops, and improve the harvest.

Q Why should I prune my grapevines?

A You must prune grapes (Vitis spp.) to get good crops. Many varieties are rank growers; an unpruned plant can spread quickly over a large area, forcing its energy into the vine rather than into the production of grapes.

Grapes grow mostly on one-year-old wood (canes). As an unpruned vine matures, it carries more and more wood that is much older and thus becomes not only tangled but unproductive as well.

Q How do I go about it?

A Allow the canes to grow one year and bear fruit the next, then prune them off. Each summer your plant should have canes at two stages of growth: canes that grew last year and are now bearing and new canes that will bear next year.

Grape-pruning methods vary because different varieties grow at different rates and the pruning must be adjusted accordingly. Pruning also varies with soils and climates.

Keep in mind the following when pruning grapes:

Prune to keep the vine to a manageable size.

Prune to keep the vine to a manageable size.

Prune to direct the energy of the vine into producing fruit rather than stems and leaves, and to keep the crop growing close to the main stem so that the sap doesn’t have to travel far to produce grapes.

Prune to direct the energy of the vine into producing fruit rather than stems and leaves, and to keep the crop growing close to the main stem so that the sap doesn’t have to travel far to produce grapes.

Prune to let in sunlight so the fruit can ripen. Grapes must ripen on the vine because, unlike most other fruits, they do not continue to ripen after they are picked.

Prune to let in sunlight so the fruit can ripen. Grapes must ripen on the vine because, unlike most other fruits, they do not continue to ripen after they are picked.

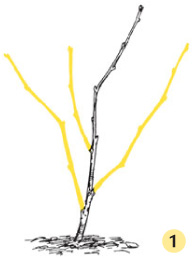

Q Do I need to prune grapes when I plant them?

A Because pruning at planting time is so important to a grapevine’s future success, most nurseries prune the vines before they sell them. Ask the nursery if vines are pruned and ready to plant. If not, do it yourself, unless the vine is potted with its roots intact. You must steel yourself and prune heavily, so the roots will grow faster than the top and stimulate the vine to get off to a strong start. It will begin bearing heavy crops in two or three years.

1. Prune away all side branches.

2. Cut back the main stem to two or three buds, so that it is no more than 5 inches tall.

Q Do bush fruits and grapes need pruning?

A Yes. Although wild and neglected bushes and vines bear without pruning, you’ll get better, more abundant crops if you prune regularly. Also, pruning makes it easier to pick the fruit. Proper pruning extends the useful life.

Pruning methods for bush fruits, brambles, and grapes are somewhat different.

Q When should I prune my grapevine?

A Always prune when your vine is dormant — anytime after the leaves drop in the fall but before the buds begin to swell in the spring, provided the temperature is above freezing. Most northern gardeners choose early-spring pruning so they can cut off winter injury at the same time.

Q I want to plant a grapevine. What are my growing options?

A You have several options, depending upon your goal:

On an arbor. This way, you can enjoy the beauty of the vines while watching the ripening grapes hang from overhead.

On an arbor. This way, you can enjoy the beauty of the vines while watching the ripening grapes hang from overhead.

On a trellis. This enables you to espalier the vines against a wall or a building.

On a trellis. This enables you to espalier the vines against a wall or a building.

Over a fence. A casual look that softens a fence’s lines will provide you with a tasty, easy-to-reach harvest.

Over a fence. A casual look that softens a fence’s lines will provide you with a tasty, easy-to-reach harvest.

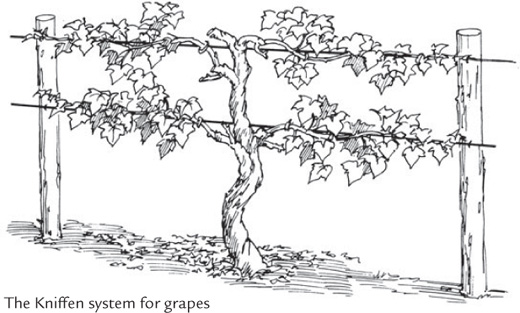

The Kniffen system. This type of fence is meant to be highly practical and is not for show. However, grapevines grown in this way are easier to care for and most likely to be healthy and productive. (See Kniffen system, page 272.)

The Kniffen system. This type of fence is meant to be highly practical and is not for show. However, grapevines grown in this way are easier to care for and most likely to be healthy and productive. (See Kniffen system, page 272.)

As freestanding plants. Some gardeners, especially wine producers, like to prune their vines so that they have a single, long, tall trunk, like a cordon. Each year after fruiting, they cut back all the canes almost to this trunk, leaving a few short stubs to bear fruit and from which the new canes appear.

As freestanding plants. Some gardeners, especially wine producers, like to prune their vines so that they have a single, long, tall trunk, like a cordon. Each year after fruiting, they cut back all the canes almost to this trunk, leaving a few short stubs to bear fruit and from which the new canes appear.

Q I’m planting grapes to grow over an arbor. How should I prune the vines?

A Again, your pruning depends upon your goal:

ORNAMENTAL. If you want a thick, shady vine with a few grapes hanging on it for effect, prune only to keep it from becoming overgrown.

ORNAMENTAL AND PRODUCTIVE. If you want grapes as well as beauty, prune annually to get rid of all wood over one year old. Cut back part of the year-old wood too, leaving only enough to cover the arbor and produce grapes the following year.

Q What’s the easiest way to grow grapes? We don’t want fancy trellises, just a reliable way to grow healthy grapes to eat.

A One of the easiest and best ways to care for grapes is the Kniffen system. Begin by choosing a good site. Your vines need as much sun as possible and as little of the chilling north wind as you can manage.

Each year, thin fruit clusters whenever too many appear. Usually a healthy, vigorous vine will produce from 30 to 60 bunches a year, with an average of 8 to 15 per branch. Don’t allow the plant to produce a greater number, because overproduction weakens the vine, and you’ll get quantity rather than quality.

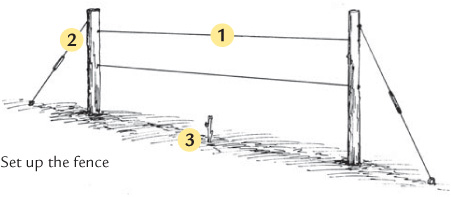

Q What’s the best support for growing grapes?

A You need a sturdy fence for the Kniffen system. Install two strands of smooth 9- or 10-gauge wire, stapled on posts set solidly in the ground and spaced about 8 feet apart. Space the lower wire about 3 feet above the ground and the second about 2 feet higher (1). Brace posts at their ends so wires won’t sag when loaded with fruit and vines (2). Plant each grapevine midway between the posts (3).

Q How do I start with the Kniffen system?

A Implement this method as follows:

1. After the initial cutting back at planting time (see page 269), during the first summer allow vines to grow naturally. Remove side sprouts so vines grow upward toward the wires.

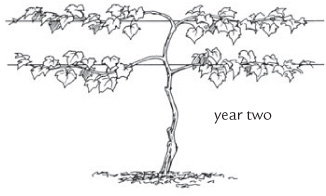

2. During the second summer, by pinching and pruning, allow two vines to grow along the wires in each direction — four in all. If the vines grow well, they should cover the wires by summer’s end (if they grow more, cut back extra growth and side branches after the first hard frost). Grape tendrils should wrap around wires and hold vines securely. If any need to be reattached, use narrow plastic ribbon (not tape), which won’t cut into tender bark.

Q How do I prune once my grapes start bearing?

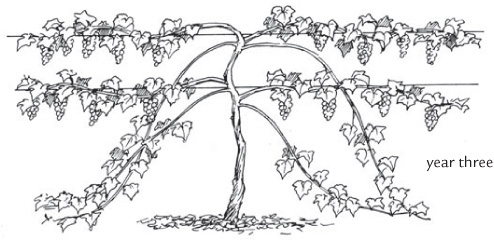

A The third year is your first bearing year! Let four more new vines grow parallel to those of the previous season. These newcomers replace ones that grew the second year. Let these droop on the ground until you cut off the old vines and are ready to fasten replacements to the wires.

Meanwhile, year-old vines should bloom and set grapes all along the wires this summer. Don’t allow too many bunches to form, because overbearing weakens the plant and jeopardizes future crops. Remove some clusters of tiny grapes if more than three or four bunches form per vine. Continue to pinch back new growth headed in the wrong direction all season. Four new canes are all you’ll need.

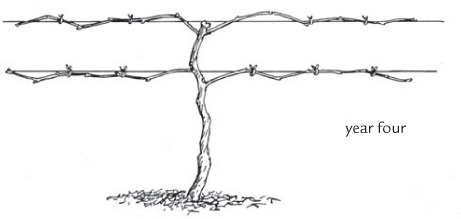

In late winter or early spring, cut off the four fruiting canes from the previous year. Make sure that you secure four new canes to the wires. These replace last year’s bearing vines and produce this year’s crop. Cut off extra growth, and during summer, pinch new canes occasionally to train four more canes that will replace those presently bearing. Repeat this process every year.

Q How do I go about rejuvenating a neglected grapevine?

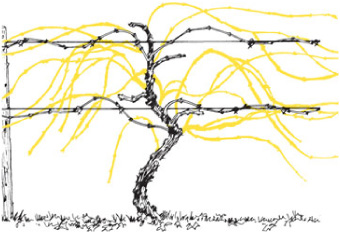

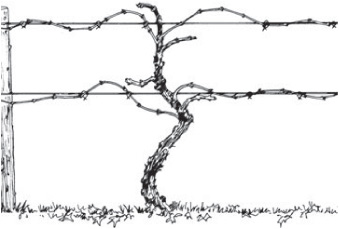

A If the vine is badly overgrown, spread out the work over several years with the idea firmly in mind that you will eventually get the vine back to a single trunk with only four strong, well-spaced branches. Then you can train it into a Kniffen or other manageable system. Have a truck standing by to haul away the prunings, or plan a brisk bonfire in a safe place, because you’ll have to get rid of lots of dead wood.

Try the following steps:

1. When the vine is dormant, choose a main trunk and remove all competing stems.

2. Choose two canes on each side (this year’s growth) and flag them. These will be the bearing canes for this season.

3. Cut back two more canes on each side, leaving two buds on each. These spurs will produce the bearing canes for the following year.

4. Prune out everything except the flagged canes and the spurs. Shorten the flagged canes to about 10 fruit buds each for best productivity, and tie them loosely to the wires.

Q Parts of an old grapevine have taken root. Can I make new plants from the rooted pieces?

A Vines that trail over the ground for many years often root and form many new plants, which can be salvaged. In early spring, cut them back to about a foot. Then dig them up with a ball of soil and replant them where you please.

If you don’t need or want new plants, cut off all rooted vines at ground level and don’t allow them to grow back. Mow or spread heavy mulch over the area to control any regrowth.

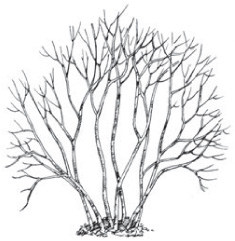

Q Do bush fruits need much pruning?

A Bush fruits such as currants, elderberries, gooseberries, blueberries, and cranberries are not nearly as demanding as the tree fruits, brambles, or grapevines, which need annual upkeep. Some old farmsteads have currant and goose-berry bushes that produce large crops of excellent fruit after decades of neglect. They are resistant to most diseases and insects and, with the exception of blueberries, not at all fussy about soil. Each bush produces better with a little care, including pruning.

Q Should I prune a blueberry bush before planting?

A Plants in containers or growing with a well-wrapped and undisturbed ball of earth don’t need pruning for the first few years, except to remove dead or damaged branches. Treat a bare-root fruit bush just as you would any low-growing shrub. Cut off any dead or damaged roots or branches. Also remove any crossed or rubbing branches.

Q How should I prune blueberry bushes for lots of fruit?

A Compared to other bush fruits, highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) is a slow grower, taking as long as a decade to come into full production. So that you won’t delay bearing, avoid pruning for the first three years, except to remove dead or broken limbs.

Blueberries tend to grow in a bushy manner with lots of small twigs. As a plant gets older, the twigs get thicker and bear less fruit. Follow these steps to keep mature bushes bearing abundant crops:

1. Cut two or three of the older main stems right back to the ground. Also remove any dead branches.

2. Thin out about half of the end twigs from the remaining branches to stimulate the plant to bear more heavily. Ideally, the pruned plant will have canes growing tighter at the base than at the top, which should be fairly open and without crossing stems.

Blueberries can be grown almost anywhere the weather is not too extreme. They do require acidic soil (pH of 4.5 to 5), so amend the chosen spot at planting time if necessary. And choose a variety that is known to do well in your climate. There are dozens to choose from, especially in specialty nursery catalogs.

IN MILD CLIMATES. As with many other fruits, blueberries grown in areas where the winter is mild should be pruned heavily. You can do this any time from when the leaves come off in the fall to the time that growth starts in very early spring.

IN COLD CLIMATES. If you have a short growing season and a cold winter, prune lightly each year, experimenting until you find what amount seems most beneficial to the plant. Do this in early spring, so you can remove any wood that was injured during the winter at the same time. Overfeeding and overpruning may induce winter injury and severely limit your crop. Be careful never to prune frozen wood, because your cut won’t seal easily, resulting in additional winter injury to the plant.

This little, three-season shrub grows wild in New England, making a dense ground cover with bell-shaped white spring flowers, sweet edible summer fruits, and red fall color. The tiny, frosty blue fruits are sweet, meaty, yummy, and better for baking than highbush blueberries, which are more watery.

Q What fruit can I grow that doesn’t need pruning every year?

A Try currants or gooseberries. Abandoned plants often continue to produce good crops for decades, although the fruit is small. Even a little pruning will improve yields, however.

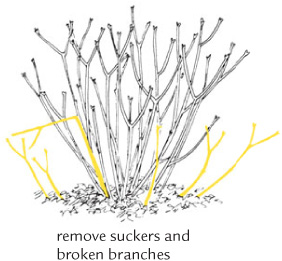

For the best yields of currants and gooseberries, a little pruning pays off. Begin to thin out your bush when it is about three years old. Stems that are older than that bear poorly and should be cut off at ground level or as close to the soil as possible. New, vigorous growth will quickly replace them. To produce its best, a currant or gooseberry bush should have wood that is one to three years old, and little or none that is any older.

SEE ALSO: Pages 285–286 for elderberries.

Q I’ve had my gooseberry bushes for two years. Do they need regular pruning?

A Usually the initial pruning will be all your bush needs for several years. Cut off any dead twigs or branches and those that have been broken by weather or birds. Otherwise, just let the bush grow.

Q Can pruning help my currants produce bigger berries?

A Yes. After your bush has borne several large crops of fruit, you may notice that it looks a bit overgrown and that the fruits are getting smaller. It’s time to thin it out. Select a few of the oldest branches and cut them right to the ground, either in late fall or in early spring. If you do this faithfully every few years, the bush should continue to produce and thrive.

Q Do currants and gooseberries perform well in the South?

A Currants and gooseberries (Ribes spp.) are cool-weather plants, grown in northern areas. Although new varieties are being developed for the South, these fine bush fruits grow best where summers are cool and winters are cold.

Q The fruits on my gooseberry bushes seem to be shrinking in size. What’s wrong?

A With heavier pruning, you can force giant-sized goose-berry varieties to produce fruit as large as grapes or small plums. Thin out the berries as soon as they form. Pick off the tiniest berries and leave the remaining ones about 1 inch apart on the branch. (With thorny varieties, however, this process may not be an entirely pleasant task, or worth the trouble.)

Q Can I make old currant bushes more productive?

A If you have a neglected bush, give it a new lease on life by cutting it off at ground level and letting a new plant grow back. Doing all this in one year would be hard on even a vigorous plant, so spread out the job over at least a couple of years.

In very early spring, before any green shows, cut off about half of the old stems at ground level, leaving any young, lively ones. That year, you should see a lot of new growth.

In very early spring, before any green shows, cut off about half of the old stems at ground level, leaving any young, lively ones. That year, you should see a lot of new growth.

The next year, cut the remaining old stems to the ground. These, too, will regrow, and you will have a completely new plant that you’ll be proud to show off, and one that will be easier to prune and care for in the usual manner.

The next year, cut the remaining old stems to the ground. These, too, will regrow, and you will have a completely new plant that you’ll be proud to show off, and one that will be easier to prune and care for in the usual manner.

Q I intend to buy an elderberry for my backyard. Does it require much pruning?

A Both wild and garden elderberries (Sambucus spp.) are a fine addition to anyone’s backyard berry patch. Elder-berry is a wonderful fruit, and I’d hate to be without it. However, plants are tall (to 7 feet) and extremely vigorous growers. Grow them only where you can keep them safely under control by mowing around them regularly. They grow well only in moist areas, and you should never plant them near a vegetable garden, flower bed, or other berries or plants.

Because they are so productive and robust, and since all the improved varieties have only recently emerged from the wild, elderberry plants need minimal pruning to keep them productive.

Q I love my elderberry! How can I keep it neat and bushy instead of tall and lanky like the ones by the side of the road?

A During the first summer, pinch off the top of the young plants to encourage side branching and earlier bearing. (Unlike the other bush fruits, early bearing won’t hurt an elder-berry plant at all.) Cut out any wood that gets broken during the winter, and remove old, corky stalks that no longer produce well. Mow or prune off the sucker plants that continually try to grow outside the clump. You can prune elderberries anytime, since they are such vigorous growers.

Q I want to grow raspberries and blackberries. What do I need to know?

A Raspberry and blackberry plants and their dozens of cousins — including the boysenberry, dewberry, young-berry, and marionberry — are usually referred to as the brambles (Rubus spp.). Unlike the bush fruits, which are really small trees, the brambles are woody biennials — actually, their canes are woody biennials. The roots are perennial, and under the right conditions, brambles will live for decades, perhaps even for centuries.

Here’s how they grow: Each cane sprouts from the roots and grows to its full height in a season. The following year it blooms, produces fruit, and dies that same season. (Everbearing raspberries follow a slightly different routine; see page 290.) At the same time, other canes are growing that will produce their fruit the following year. And so the patch marches on.

Cutting out old canes after fruiting is central to bramble-fruit culture. An old frugal Yankee once said that he “warn’t goin’ to cut nothin’” out of his patch, because there was always a chance that dead canes might bear something another year. In about three years, he had a jungle of dead canes and almost no fruit — his patch had killed itself by overpopulation. Anyone who enjoys wild-berry picking has seen this happen to an uncultivated patch — in a few years, there are no plants left. There is a reason: Nature arranged it so that brambles are an interim crop, holding their own until trees get a foothold. Pruning, however, can make a difference.

Q Should I prune brambles the first year I plant them?

A You don’t have to cut back the tops, except for damaged stems. If you bought them in pots, untangle any encircling roots. For bare-root shrubs, prune off broken roots.

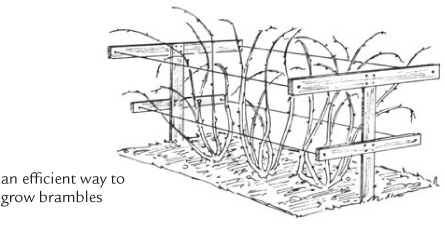

Q What’s the best way to grow brambles?

A Set the plants 24 to 36 inches apart in a straight row. If you plant more than one row, keep the rows at least 6 feet apart. While this may seem like wasted space, berry plants are such virile growers that they soon make a wide row. Unless you leave adequate space, you’ll have no room to walk between the rows. Also, by spacing them correctly, you won’t have to cut out a lot of thorny growth. Place bare-root blackberries and raspberries 1 inch deeper in the soil than they grew at the nursery. Check the dark soil line near the roots to determine how deep they were previously buried.

Support mature plants with double rows of smooth wire on each side of the row.

Q How do I prune raspberries and upright blackberries?

A In late summer after you have picked the berries, remove old, dying canes that produced fruit this year by cutting to the ground. Remove (or mow over) any plants coming up between the rows. Before winter, also:

Cut out small, weak canes at ground level to divert the plant’s energy into the main stems.

Cut out small, weak canes at ground level to divert the plant’s energy into the main stems.

Thin strong canes so they are at least 5 or 6 inches apart.

Thin strong canes so they are at least 5 or 6 inches apart.

Cut back the remaining canes to about 5 feet in height to make them stiff enough to stand upright over the winter without support.

Cut back the remaining canes to about 5 feet in height to make them stiff enough to stand upright over the winter without support.

Q I just bought some everbearing raspberries. How should I prune them?

A Several varieties of red and yellow raspberry plants are sold as “everbearers.” They do not produce constantly throughout the summer, as the name implies, but they do bear a crop in midsummer on one-year-old canes (as do most raspberries) plus another, usually smaller, crop in the fall on the new canes that have just finished growing.

If you have only one kind of raspberry and it is an ever-bearer, you can treat it just as you do the regular bearers. Cut out the old canes just after they finish bearing their summer crop, then harvest a fall crop off the new canes, leaving them to produce again the following summer.

However, many gardeners who have both regular and everbearing varieties prefer to skip the summer crop on the latter to harvest a bigger fall crop. They do this by treating the raspberry canes as annuals, cutting them to the ground right after the fall crop is harvested. Since there are never any one-year-old canes, there is never any summer crop the following year. The fall harvest is not only larger but earlier as well, since all the plant’s energy goes into it. There’s only one thing as tasty as a fresh raspberry in season, and that’s a fresh raspberry out of season.

Q What should I do with all the little blackberry plants that formed last summer where the ends of long trailing canes curved down and touched the ground?

A Purple and black raspberries and trailing blackberries form new plants by a process known as tipping. In late summer, their long canes bend over until the ends touch the soil; roots then grow at these tips and a new plant is born. Keep them under constant control, just as with suckers.

Q I want to plant only one bush. Do I need a fancy support?

A If you have only one bush, try tying the branches to a post. That should be sufficient.

Q I’m finding my raspberries hard to control. How can I keep their suckers from taking over my small garden?

A The large root systems of red and yellow raspberries and upright-growing blackberries send up lots of suckers, which sometimes appear several feet away from the row. Always cut them off at ground level. Mulch generously, and mow or cultivate between the rows.

Q What’s the best way to grow vine-type brambles like boysenberries?

A Vinelike blackberries and the closely related dewberries, boysenberries, and youngberries grow taller than other brambles. Fasten them to wires about 5 feet high supported by posts. Allow three or four strong canes to grow from each plant and thin out the others. Allow those that grew the previous season to bear fruit and another set to grow as replacements to produce the following year’s crop. Cut out the old canes soon after you harvest the berries. The following year, fasten the new canes to the wires. Grow black and most purple raspberries the same way.

Q I’m starting over because my bramble patch became a jungle. Any tips?

A Every summer, without fail, cut out old canes as soon as they finish bearing. You can identify them by their appearance: they are tan or brown and tend to be woody, in contrast to the new canes, which are young and green.

Thin out the new canes to allow better air circulation and reduce the chances of mildew, spur blight, and other diseases. Thinning also results in larger berries. First, cut out all weak, small, short, and spindly canes. Then thin the healthy, large canes so that the remaining ones are 6 inches apart.

Cut back tall-growing brambles to about 5 feet, but short-growing varieties need only a few inches snipped off. Pruned canes tend to stand winter winds and snows without breaking and are better able to hold up the following year’s fruit without flopping to the ground.

Burn old canes or get them out of the neighborhood as fast as possible. Never use the canes as mulch or put them in the compost pile, because they rot slowly and may be harboring harmful insects or diseases.

Q Can pruning help keep my brambles healthy and free from pests and diseases?

A Check your patch often throughout the summer to see that diseases and insects haven’t launched an assault. The two most common maladies are both easily treatable by timely pruning:

SYMPTOM. Whole canes wilt and die.

CULPRIT. Spur blight, a common disease of bramble fruits, is infecting your plants.

TREATMENT. Prune out and burn or bury all the dying canes as soon as you notice them.

SYMPTOMS. In early summer, some of the top leaves on the new canes have wilted and the tops are drooping.

CULPRIT. The cane borer. Look for two parallel rows of dots just below the wilted portion; a cane borer has deposited an egg right between the two circles.

TREATMENT. Cut off the top of the cane 6 inches below the lower circle and burn it, egg and all. If you don’t, the resulting grub will live up to its name by boring down the cane and wrecking it. Then, down near the roots, the grub will develop into a clear-winged moth that will fly about your berry patch some night spreading more eggs and mischief.

SEE ALSO: When Galls Are Not Harmless, page 85.