Many companies focus their sustainability efforts on reducing the impacts of sourcing, making, and delivering their products. This approach targets the so-called cradle-to-gate stages of the supply chain in that the company is focused on the origins and handling of the product up to the company's “gate,” which is the point at which the customer takes possession of the product. But, as mentioned in previous chapters, some of the largest environmental impacts take place at the end of a product's life.

In 2008, the CBS investigative journalist Scott Pelley, visiting the city of Guiyu in southeastern China, uncovered a veritable post-apocalyptic wasteland within a sprawling area where 5,500 family workshops were handling discarded electronics.1 Pelley was horrified. Acrid smoke tainted with lead and dioxin drifted into the air. Open vats of acid and chemicals, some stirred by hand, stripped metals off plastic parts. Smoky open fires melted solder off old circuit boards. Incinerators burnt off the plastic attached to the metal skeletons of PCs and other pieces of consumer electronics. Nearby drainage trenches carried heavy metals into local streams and rivers.2 Air quality studies of Guiyu found elevated levels of lead and other atmospheric contaminants, which, based on well-documented research,3 increase residents’ risks of developing neurological, respiratory, and bone diseases.4

Guiyu is one of the largest electronic waste (e-waste) recycling facilities in the world. Yet China is not the only country where these hazardous electronic waste processing centers operate. Such unchecked recycling activities take place in many developing countries including India, Nigeria, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Benin, and Liberia.5

Revelations of the dangerous recycling practices found at many sites in the developing world tainted the green image of recycling. Moreover, images of gutted product carcasses at these e-waste recycling hellholes often showed the nameplates of popular electronics brands such as HP, IBM, Epson, Dell,6 Apple, Sun, NEC, LG, and Motorola.7 The environmental damage from unchecked waste processing has attracted increasing scrutiny from governments and environmental activists, resulting in increased business attention to managing what happens to products after consumers are done with them.

Managing end-of-life products, scrap, and waste does not always increase costs; in some cases, it can provide business opportunities through lower-cost materials, supply security, avoided costs of disposal, and avoided liabilities. Recycled aluminum, for example, offers a way to make more aluminum cans without investing in more aluminum mines and smelters. Furthermore, much of the cost of virgin aluminum is in the energy used to smelt ore into metal. A beer can made from recycled material requires 95 percent less energy to produce than one made from virgin material, according to the Aluminum Association.8

The opening of a new Primark clothing store provokes a feeding frenzy of shopping for fashionable frippery.9 Primark specializes in selling trendy clothes at such low prices that anyone can be a fashionista.10 The result is hyperfast fashion retailing with environmental impacts on both the upstream and downstream ends of the supply chain.

The frenzy of consumption at Primark's stores is backed by a frenzy of production at Primark's suppliers. On the upstream side, Primark's low costs mean that its suppliers—mostly in the developing world—pay workers a pittance to toil under deplorable conditions by Western standards (see the story of the Rana Plaza building collapse in chapter 2; Primark items were found in the rubble). On the downstream side, the fast-fashion retail model practiced by Primark and others also encourages consumers to buy large quantities of apparel and discard the cheap merchandise after only a few uses. However, bargain fashion is not the only source of discarded apparel. Some high-end brand owners prefer to destroy surplus inventory rather than cheapening their brand by marking it down, selling it through discount outlet channels, or donating it. These behaviors send 21 billion pounds of textiles to landfills each year.11

As the global population grows in number and in affluence, solid waste grows faster than any other environmental pollutant, including greenhouse gases.12 The rate of waste generation has grown tenfold in the last century. The typical US resident uses and discards twice as many goods as they did 50 years ago13 while US per capita GHG emissions have actually fallen slightly over the past 50 years.14 Although the average person treats waste as “out of sight, out of mind,” the problem is becoming increasingly visible. For example, in 2013 a barge loaded with six million pounds of garbage from an overfilled landfill in Islip, New York, floated aimlessly around the Atlantic Ocean for five months. After being rejected by six states and three foreign countries, it ended up in the headlines and right back where it had started.15 And the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a “floating junk yard on the high seas” stretches for hundreds of miles in the North Pacific Ocean. It is made up of nonbiodegradable materials including plastic bags, bottles, and other products such as tires and computer parts.16 It may be out of sight of land except for the dead seabirds and whales that wash up on beaches after ingesting fatal quantities of the flotsam and jetsam of modernity.

Although some companies are using more recycled material, most supply chains remain “linear,” and most products end up in landfills or incinerators. In 2013, Americans generated approximately 254 million tons of municipal solid waste, about 4.4 pounds of trash per person per day.17 Although recycling rates have grown from 8 percent in 1970 to almost 35 percent in 2013, the United States still trailed behind Germany (65 percent) and South Korea (59 percent).18 Significant government efforts and programs are attempting to change consumer behavior and encourage recycling. For example, the EU is seeking a 50 percent recycling rate by 2020, primarily driven by increasing the recycling rates in countries like Spain (30 percent), Poland (29 percent), and Slovakia (11 percent), which had been lagging behind.

While working on his Master of Science degree in engineering physics at Lund University in 1990, Thomas Lindhqvist put forth a radical idea in a report to the Swedish Ministry of Environment.19 He recommended that the organizations that profited from the production and sale of a product should also be held responsible for the costs of its disposal. Rather than foist the impacts of disposing end-of-life products onto municipalities, or engage in uncontrolled dumping, manufacturers would be expected to directly or indirectly handle these disposal tasks or costs.20 This concept of extended producer responsibility (EPR) expands manufacturers’ environmental responsibilities from “cradle-to-gate” to “cradle-to-grave.”

Electronic waste in the EU is expected to grow from 9 million tons per year in 2005 to 12 million tons per year by 2020.21 Worldwide, the total in 2012 was 50 million tons.22 Owing to its residual value and its toxic risk if landfilled, e-waste is often exported from EU countries to developing nations where scenes like the uncontrolled processing in the city of Guiyu mar the landscape.23

To restrict hazardous handling of e-waste, the EU introduced the Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Directive in 2006, a performance-based (as defined in chapter 10) EPR regulation. The EU edict “puts the onus on distributors to accept WEEE from consumers on a one-to-one basis when selling new products, although Member States can deviate from this requirement if they can show that an alternative procedure is just as convenient for consumers.”24

Other jurisdictions have implemented similar rules. In 2013, EPR regulations were in force in California for carpet, paint, and mercury thermometers. Canada, Japan, and several other countries require EPR for packaging, batteries, and hazardous substances.25 In 2010, Brazil introduced its own National Solid Waste Policy (NSWP) based on EPR principles and WEEE regulations.26 The Brazilian policy applies to pesticides, batteries, tires, light bulbs, hazardous waste and associated packaging, lubricating oils and their packaging, and electronics products and components.27,28

Companies assessing the impacts of postconsumer products can begin by examining the possible fates of these goods. Products may end up buried in a landfill, littered on the ground, dumped at sea, incinerated, or recycled into other products. Of prime concern are the potentially toxic effects that disposal may have on people, wildlife, land, and water. The toxicity assessment includes not only the manufacturer-specified bill of materials (BOM) ingredients of a given item but also the likely by-products emitted during waste handling. For example, the decay of foods and wood fibers (e.g., packaging) in a landfill can generate methane, a potent GHG. Metals, dyes, and chemicals in a product can break down and leach into groundwater. Incineration of some products, such as those made with PVC (polyvinylchloride), can release irritating particulates, as well as highly toxic dioxins. Of greatest concern are heavy metals such as mercury, lead, and cadmium, which can cause permanent neurological damage, especially in children. Other concerns include carcinogens such as arsenic, beryllium, cobalt, hexavalent chromium, nickel, and a host of dangerous petrochemical compounds.

A now-ubiquitous icon on many cans, bottles, and packages hints at the main categories of corporate strategies for reducing the volume of waste arising from end-of-life products.

The recycling symbol—a Möbius strip triangle of arrows—encourages consumers to follow the “3R's”: reduce, reuse, and recycle. The US EPA's “Solid Waste Management Hierarchy”29 ranks the three R's by their environmental benefits. At the top of the hierarchy is reduction: minimizing initial resource consumption which curtails end-of-life waste production. Reduction activities take place in the other phases of a product's life, rather than at the end-of-life. Reuse seeks ways to prolong the life of the company's products, often involving secondary markets, sharing, and reverse supply chains by which companies refurbish and resell pre-owned products. It also includes the reuse of product components. Finally, recycling also requires a reverse supply chain, which moves used products to facilities where they can be deconstructed and their components reprocessed into their constituent raw materials that are then remanufactured into other products. Products made from recycled components are often marketed to “green customers.” If none of the three R's are possible, end-of-life products are either burned to recover energy or disposed as waste in a landfill, which may incur costs of additional treatment.

Cars may be the most reused consumer product on the market and illustrate how the lives of products can be extended through resale. In the United States, used car sales outpace new car sales, with the average car having about three owners during its lifetime.30 An entire industry of parts suppliers, parts retailers, service providers, dealers, and used cars appraisers serves this large market. Automakers even aid in resale through manufacturer-certified pre-owned vehicle sales as well as by managing supply chains of certified parts. Other durable goods that are readily sold and reused include trucks, aircraft, electronics, appliances, and tools.

Consumers often sell, give away, or donate a wide range of used household goods rather than discard them, according to an RMIT University survey of 306 Melbourne households.31 Secondhand resale channels included traditional used items in secondhand retail shops, online exchange/reselling websites like eBay, newspaper ads, and special publications. The researchers also found that significant numbers of goods had been donated to charities or gifted to family or friends. And Australians are not alone in their impulse to get the most value out of their used household items.

Craigslist, with its local exchanges and no fees, grew from humble beginnings to become a major force in the market for consumer-to-consumer exchange and sale of secondhand goods. The company, founded in 1995 by Craig Newmark, started as a free email newsletter that listed events around San Francisco.32 It evolved into a website on which anyone could post free33 classified advertisements across a wide variety of categories seeking or offering everything from jobs to electronics to personal companionship. In the two decades following its creation, Craigslist has expanded to cover most major cities. In 2013, the site saw more than 1.5 million new posts globally each day,34 with about two-thirds of the ads being items “for sale.”35 These posts generally connect buyers with sellers in the same region, city, or neighborhood, leading to face-to-face exchanges, and giving every person access to a large pool of buyers and a way to advertise and sell used items without transaction fees.36

Companies can capitalize on rapidly changing technology products by supporting reuse of older technologies. For example, smartphones evolve rapidly, and some consumers only want the latest and greatest models. In fact, more than 100 million cell phones are discarded each year in the United States alone.37 However, although last year's model might be passé to early adopters, many consumers don't mind an older model if the price is right. In 2011,38 ecoATM, LLC in San Diego began installing kiosks at malls and other retail locations where consumers could sell back their used phones, tablets, or MP3 players and instantly receive cash. The transaction takes just minutes, and by September 2014, the company had installed 1,100 of the kiosks across the United States.39

The kiosks use machine vision and machine learning algorithms to determine the device's model and condition and then instantly match the phone with an industry buyer who has already agreed to a price. “Imagine a spreadsheet that's 8 columns wide and 4,000 rows deep,” said Mark Bowles, ecoATM's founder. “And then you go through that 4,000 by 8 pricing matrix and you bid in advance on any one of those cells that you want. … If you end up with the highest price in that pre-auction, then you win that cell.”40

Yet ecoATM does not sell to just anyone. Bowles explained that ecoATM screens buyers for proper electronics disposal practices, as well as being “good business partners.” The company holds on to the devices for 30 days to give law enforcement agencies time to recover them in case the device has been stolen.41 Once that interval has passed, the buyer wires the agreed-upon payment and ecoATM sends the phones. The customer selling the phone, meanwhile, walked away 30 days earlier with cash in hand.

EcoATM is not the only player in this market. ReCellular began recycling cellphones from collection drives and later expanded into buying back individual phones by mail. In 2012, the company resold or recycled 5.2 million phones, up from the 2.1 million it handled in 2007.42 In 2013, about 60 percent of ReCellular's stock was sold within the United States.43 Furthermore, large retailers, notably Best Buy and Amazon, began selling refurbished phones, joining the recycling business opportunity.44 Mainstream companies in the smartphone industry also participate in recycling and reusing. For example, both Apple45 and Verizon46 operate buyback services for smartphones.

It's not every day that someone gets a call saying, “Give me your oldest batteries.” But that's what suppliers and customers heard from Pablo Valencia, General Motors’ senior manager of battery lifecycle management, when he wanted to test a new extended reuse concept in conjunction with the Swiss power technology giant ABB and Duke Energy, the largest utility in the United States.47 Valencia realized that old products do not have to be used in the same way that they originally had been. Electric and hybrid vehicles require high performance from their batteries, both in terms of high power for vehicle acceleration and high total energy for vehicle range. “In a car, you want immediate power, and you want a lot of it,” said Alexandra Goodson, business development manager for energy storage modules at ABB.48 Unfortunately, as the battery ages, its performance on both dimensions declines, almost as if both the car's engine and fuel tank were shrinking. But even if the battery can no longer deliver satisfactory power and range in a vehicle, it can still store and deliver significant amounts of electricity for other applications. GM's boxy demonstration unit showed that a cluster of five old Chevy Volt batteries could store and provide enough wall-outlet electricity to power three to five average American homes for up to two hours.49

This concept may be (a small) part of the solution to a looming problem in national electrical grids: the mismatch between electrical demand and the respective supply. The rising adoption of renewable power such as wind or solar adds unpredictable supply, and the recharging of electric vehicles adds new spikes to the demand. “Wind, it's a nightmare for grid operators to manage,” said Britta Gross, director of global energy systems and infrastructure commercialization for GM. “It's up, down, it doesn't blow for three days.” Moreover, if electric vehicles become popular, then tens of millions of commuters will be plugging in their vehicles at the end of the day, just as solar power output ebbs into night. “Our grid, and most electricity grids, are not really designed to handle that kind of rapid swinging. Storage can help dampen that out,” said Dan Sowder, senior project manager for new technology at Duke Energy.50

GM is not the only automaker looking into secondary markets for used electric car batteries. Nissan North America, ABB, 4R Energy, and Sumitomo Corporation of America are building grid storage systems using old Nissan Leaf batteries. In addition, start-ups such as Green Charge Networks are selling prepackaged units of car batteries that enable commercial users, such as retailers 7-Eleven and Walgreens, to buy grid power when rates are low—to charge the battery packs—and then run their facilities off batteries when rates are high.51

Every day, Subaru's Indiana factory52 receives truckloads of wheels secured by small temporary brass lug nuts. In the past, Subaru discarded these nuts—some 33,000 pounds a year. However, as part of its waste reduction program, Subaru started collecting and returning the lug nuts, working directly with its wheel supplier to reuse them until they are no longer serviceable, at which point they are recycled for brass material.53

Even the incidental materials used for packaging can offer an opportunity for reuse. Subaru returns Styrofoam forms used to cushion delicate components on their trip from Japan to Indiana so that they can be reused in future shipments. After five reuse cycles, the Styrofoam ends up in Japan, where 85 percent of it is recycled.54 By converting consumables into assets, the cycle times become part of the sustainability metric: the faster the return of these assets (be it packaging, lug nuts, Styrofoam, or whatever) the higher their utilization and the fewer the number of consumables in the system.

Subaru's work to convert disposable items into reusable assets was part of a broad program to reduce solid waste. “People still think that it costs too much money to be environmentally friendly,” said Denise Coogan, manager of safety and environmental compliance at Subaru of Indiana. “That's an antiquated idea. Waste is money: wasted time, wasted material. The first years cost us financially, but after you get over that hump, you see the [monetary gains] take off exponentially.”55

The benefits of reusable containers may go even further. Office Depot Inc., for example, delivers some products in reusable plastic totes instead of cardboard boxes.56 Estimates suggest that the useful lifetime of reusable plastic containers ranges from 5 to 20 years, with 4 to 25 uses per year.57

When a company's product can no longer be reused by another customer, the next step in the end-of-life handling hierarchy is recycling the item's constituent materials. Recycling involves “separating, collecting, processing, marketing, and ultimately using a material that otherwise would have been thrown away,” according to the US EPA.58 Unlike the supply chain for reuse, which may be relatively simple in routing reusable goods from one customer to another, the supply chain for recycling may be much deeper and loop back to the deeper supply chain tiers that handle raw materials.

Another large reverse flow stream is consumer returns of new products, which have always presented a challenge to retailers and manufacturers. “With returns, you are working against the clock. The longer the product sits in storage and more touch points it receives, the less value you may recover,” said Ryan Kelly, senior vice president of sales, strategy and communications at GENCO, a FedEx company.59 Companies must assess the returned item for damage and refurbish it for resale as needed, sometimes shipping it back to the manufacturer for proper handling. Dealing with returns has worsened with the growth of omni-channel retailing, in which consumers expect to be able to return online purchases to a retailer's local store. Not only is the return rate of online purchases higher than the rate for in-store purchases (18–25 percent versus 8–12 percent), but the local store may not even carry the returned item.

Whereas retailers are the (downstream) end of the commercial supply chain of many products, they can also be the (upstream) beginning of the recycling supply chain for end-of-life products. For example, Staples sells new toner and ink cartridges and also provides convenient recycling drop-off bins for used toner and ink cartridges in its stores. To encourage recycling, the retailer offers a $2 reward per cartridge (with some restrictions) that can be used to buy more printer cartridges.60 The result is a 73 percent recycling rate. Like Staples, other retailers promote recycling to encourage consumers to visit their stores. For example, some Best Buy programs provide gift cards in return for recycled products,61 while customers who recycle ink and toner cartridges at Office Depot get rewards points that can be redeemed for merchandise discounts.62

Staples accumulates and consolidates the used cartridges and transports them (and other recyclables) back to its distribution center, using the backhaul capacity of its trucks. Some cartridges go back to the original manufacturer and others go to an e-Stewards certified recycling partner of Staples.63 (e-Stewards is a global collective of individuals, institutions, businesses, NGOs, and governmental agencies “upholding a safe, ethical, and globally responsible standard for e-waste recycling and refurbishment.”64) As of 2014, Staples was recycling 63 million cartridges per year.65

Retailers are not the only locations where downstream becomes upstream. In some cases, OEMs have their own direct collection programs using mail, prepaid parcel delivery services, or other customer service programs. For example, HP printer cartridges come with a special small, sturdy envelope with instructions to put the used cartridge in it and mail it (free of charge) to an HP processing center. IBM operates what it calls Global Asset Recovery Services (GARS), which offers collection of old IBM equipment from corporate customers and combines reuse, recycling, and safe disposal of discarded equipment.66

In some communities and for some materials, the collection stage of the recycling supply chain is integrated into the local solid waste collection process. These household and local business recycling programs are a key part of the supply chain for recycled glass, metal cans, plastic containers, paper, and cardboard.

The first positive outcome of recycling end-of-life products is a reduction in the volume of the waste stream. The natural rate of recycling of a company's products is a function of the ease of collecting them, the costs of recovering recyclable ingredients, and the value of the recovered materials. Actual recycling rates vary by material (98 percent of lead-acid batteries are recycled compared to 55 percent of aluminum cans67), as well as by country (recycling rates for plastic waste are 77 percent in Japan versus only 20 percent in the United States68). That which cannot be recycled ends up incinerated or buried in a landfill or washed out to sea.

Lacking its own network of retail outlets, Dell created a channel for collecting e-waste by collaborating with Goodwill Industries, a 2,000-outlet charity that collects and resells lightly used merchandise.69 Under the Dell–Goodwill partnership, consumers can drop off computers and other technology products, even non-Dell ones, at Goodwill's donation sites around the United States. The donated electronics are handled in one of three ways. First, Goodwill refurbishes and resells any newer devices that still have some life in them. Second, the modular nature of computers means that parts such as memory, storage, and peripheral cards can be sold for use in other PCs. Third, any otherwise unusable items or parts are carefully recycled by Dell.70

Dell's partnership with Goodwill also serves both companies’ social responsibility goals. The increased stream of donations supports Goodwill's mission of helping people with disabilities by providing training in refurbishing PCs and working with technology. In addition, this program allows Goodwill customers to purchase relatively modern, functional technology at a low price.71

Dell uses two other programs to collect e-waste from its customers, a common pattern by which a company uses multiple collection streams to maximize reuse and recycling. Specifically, the company collaborates with FedEx on a free mail-in program. Whereas the Goodwill partnership accepts any kind of computer from any consumer, the mail-in program is restricted to Dell customers who can send in an old Dell or trade-in a non-Dell computer when they buy a new Dell.72 For its large enterprise customers, Dell operates an asset resale and recycling services unit that manages the collection, resale, reuse, and recycling of an organization's computers. As of 2015, Dell had already recycled 1.42 billion pounds of electronic waste towards its stated 2020 goal of 2 billion pounds.73

Observers might wonder why some sections of the Port of Los Angeles look like a junkyard, complete with haphazard piles of rusting iron. As it turns out, this gritty corner of the port is a key link in a global reverse supply chain that moves recyclable materials and end-of-life products from areas of high consumption (e.g., the US) to areas of high production and demand for raw materials (e.g., China). Four of the top 10 exports from Los Angeles to China are recyclable materials: copper, paper or paperboard, aluminum, and iron or steel. Scrap materials are also a top-10 export from the Los Angeles customs district to South Korea, Taiwan, Germany, Malaysia, and Vietnam.74 These materials flow overseas to reprocessors, parts makers, and product manufacturers. These reverse supply chains use the ports' low “backhaul rates,” filling otherwise empty containers on their return trips.

After collection, the next step in companies’ recycling supply chains is the reprocessing of the waste and end-of-life materials into beginning-of-life ingredients for new products. In essence, reprocessing is the switchback turn where the reverse supply chain of recycling turns 180 degrees to connect with the forward supply chains of manufacturing, distribution, and retail. Many types of scrap metals and plastics can be readily remelted and directly reused as a raw material; other materials require more complex reprocessing steps. For example, e-waste contains many different materials that are “mixed, bolted, screwed, snapped, glued or soldered together; toxic materials are attached to nontoxic materials, which make separation of materials for reclamation difficult.”75 Trying to separate materials from e-waste without adequate technology can release heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, or mercury into the air, which is what takes place at Guiyu and the other unchecked sites in developing countries.76

For at least one category of material—plastics—a tiny change to product design has made reprocessing much easier. On most pieces of plastic, manufacturers have added an embossed or printed “3R” recycling triangle that also contains a code number.77 Code numbers 1 through 6 identify the object as being made of one of six very common resins that can generally be recycled (although not all community recycling programs accept all types). In the recycling world, “7” is an unlucky number; the catch-all code for “other recyclable plastics.” The code numbers help the sorting of plastics by type and help ensure the purity of the recycled plastics.

Dell's partnership with Goodwill provides the computer maker with a supply of recyclable plastic. Dell separates, sorts, and inspects the plastic coming from electronics collected at Goodwill locations and then ships bales of certain types of recyclable plastic to its supplier, Wistron Corporation. Wistron shreds the return stream and blends it with virgin plastic to achieve the required structural integrity (in 2015, the mix had 35 percent recycled content). Then it molds the plastic into new parts for Dell.78 By the end of 2015, Dell reported that 16 models of displays and three models of desktops were made with closed-loop recycled plastics.79 “This initiative is designed to reduce the dependence on natural resources, as well as extending the value of end-of-life electronics,” said Simon Lin, chairman and CEO of Wistron.80

HP recycles printer cartridges collected at drop-off points at retailers such as Staples, Office Depot, Office Max, and Walmart stores, as well as by mail directly from consumers, as mentioned earlier.81 HP sends the returned printer cartridges to a recovery plant to be disassembled. Then, the plastic portions are shredded and sent to a facility in Québec, Canada, where they are mixed with flakes of discarded beverage bottles to create raw material for the next batch of cartridges.82 The recycled resin is then sent to HP's cartridge manufacturing plants in Asia and Europe. As of April 2013, 280 million cartridges had been recycled, reducing a major waste stream and reducing the need for virgin material for new cartridges.83

In 2010, HP commissioned an independent life cycle assessment of its cartridge-recycling program.84 The analysis compared the impact of the collection, transportation, and processing of used cartridges and other recycled plastic to the extraction and processing of oil and the production of virgin plastic. The study found that recycling had lower impacts on all 12 dimensions covered in the study, ranging from reducing toxicity 12 percent, to cutting carbon footprints and water use by 33 and 89 percent, respectively.

Through programs like these, Dell and HP are beginning to create closed-loop supply chains, reducing both waste and demand for new materials. Dell's closed-loop cycle generated 11 percent lower carbon emissions compared with the use of virgin plastics.85 Ideally, end-of-life products could circulate endlessly back to beginning-of-life products—creating what the British environmental economists Pearce and Turner dubbed the circular economy.86 HP, for example, estimates that some of its cartridges have been recycled as many as 10 times.

Although the secondary market for cell phones is a recent invention, some recycling markets, such as for apparel, have existed for generations and illustrate the more complex supply chains of a mature reuse and recycling system. Thrift shops, such as Goodwill and Salvation Army in the United States, and Oxfam and Scope in the United Kingdom, have long accepted donations of clothes to be resold in their shops. As the price of new clothing fell and fashion fads accelerated, Western consumers bought more new apparel and donated more old apparel to thrift stores, yet these shops can only sell a small fraction of the donated clothes locally. As Elizabeth Kline explains in her 2012 book Over-Dressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion, the Quincy Street Salvation Army in New York City alone discharges six tons of unsellable clothes every day, and that quantity increases during the holiday season.87

Everything from hoodies to haute couture shows up in these donation boxes. To extract value from the stream of used clothes, thrift shop operators segregate the clothing by saleability. The nicest clothes go to boutiques that specialize in vintage styles. Mid-range items go to the organization's thrift shop. But the majority of the clothing, approximately 80 percent,88 is sold by the ton to global brokers and processors, not to local individuals.

Processors, like Mac Recycling in Baltimore, buy from thrift stores and ship 80 tons of clothes each week to Europe, Africa, Asia, South America, and Central America.89 Once there, still-usable clothes are sold again—sometimes with minor modifications. In India, for example, clothes sellers repurpose “many US women's nylon trousers into male laborers’ trousers by cutting off the elasticated waistband, adding drawstrings and ‘Adidas style’ white stripes down the sides.”90

Lower-quality pieces are “downcycled” into wiping cloths for industrial uses or shredded into fibers for carpets, insulation for cars or homes, or pillow stuffing. Buyers pay as little as $78 per ton—mere pennies per garment—for these discarded clothes.91 Finally, about 1 to 3 percent becomes fuel to produce electricity.92 At each stage, segregating the recycled material maximizes its value. At the same time, it displaces demand for higher-cost, higher-impact virgin products or raw materials for each segment of recycled material.

Rising from the inferno inside a coal-fired power plant, choking hot gases loft clouds of pulverized dust—so-called fly ash—into the air. Until regulations prohibited it, fly ash flew up the smokestack, filled the air with particulates, and played a major role in the debilitating and lethal respiratory illnesses associated with coal-fired heavy industry. The advent of electrostatic precipitators enabled the capture of airborne particles but created another problem: what to do with the accumulating tons of fine gray powder. American coal-fired plants produce approximately 75 million tons of such fly ash every year.93

As far as the coal-fired power plant is concerned, fly ash is a hazardous waste that has negative value. It is a costly nuisance to store, transport, and bury in a landfill. Fly ash contains significant levels of various heavy metals that can contaminate ground and surface water. In 2010, 31 coal ash disposal sites were linked to contaminated groundwater, wetlands, creeks, and rivers in 14 American states.94 When a fly ash containment pond was breached at a Tennessee Valley Authority electric generating plant in Kingston, Tennessee, in December 2008, the cleanup cost more than $1 billion.95

Even so, fly ash processing can be an example of converting an environmental liability into something of value. The high-temperature chemical reactions that occur inside a coal furnace are not unlike the high-temperature chemical reactions that take place inside a cement kiln. Depending on the type and the processing of the coal, fly ash can be used as a cementitious material in its own right or as a filler in concrete. As of 2010, about half of America's fly ash was used for cement and other similar applications.96 CeraTech Inc., for example, is using fly ash reclaimed from coal-burning power plants as the primary input (up to 95 percent) of its cement.97

Fly ash is an environmental win for the cement industry, too. Producing a ton of cement by the standard process generates about a ton of CO2 emissions.98 As a “free” waste product, fly ash requires only negligible additional energy, resulting in little incremental GHG emissions, to create cement.99 Each year, this and other uses of fly ash save an estimated 11 million tons of CO2, 32 billion gallons of water, and 51 million cubic yards of landfill space, according to congressional testimony by the Electric Power Research Institute.100

In many cases, recycling old products or parts into new ones of the same kind is not economical or even feasible. One alternative is downcycling—recycling end-of-life high-value goods into lower-valued goods. For example, at more than 450,000 locations around the world, new and old Nike shoes meet in an unusual way—wearers of new Nike shoes play and compete on sporting field surfaces made from old Nike shoes. In 1993, Nike debuted the Reuse-A-Shoe program to recover used athletic shoes as well as the scrap left over from the shoemaking process.101 Nike sliced and shredded recovered shoes into a material it called Nike Grind and sold it for surfacing high-performance tennis and basketball courts, running tracks, and other athletic surfaces.102 By 2013, the program had recovered 28 million pairs of shoes and 36,000 tons of scrap, using it to cover playing surfaces around the world.103

In 2010, clothing retailer The Gap Inc. partnered with Cotton Inc.—a research and marketing company representing upland cotton104—to launch the “Recycle Your Blues” campaign. The campaign encouraged consumers to drop off their old pairs of jeans at any of the Gap's 1,000 participating stores. Participating consumers would get 30 percent off a new pair of Gap Jeans; the old jeans were converted into UltraTouchTM natural cotton fiber housing insulation. Cotton Inc. donated the material to underserved communities and to special housing projects such as the post-Hurricane Katrina rebuilding effort. Between 2006 and 2010, Gap collected 360,000 units of denim and used them to create fiber insulation for more than 700 homes.105

In Denmark, 98 municipalities get household heat and electricity by burning garbage in 29 facilities across the country. For example, residents of the town of Hørsholm, an affluent northern suburb of Copenhagen, get 20 percent of their electricity and 80 percent of their heat from a carefully designed and managed garbage incinerator. “Constituents like it because it decreases heating costs and raises home values,” said Mayor Morten Slotved.106 About one-third (34 percent) of Hørsholm's trash goes to waste-to-energy incineration.

For unrecyclable kinds of urban waste, a well-managed waste-to-energy plant beats a landfill as the most environmentally friendly destination, according to a 2009 study by the US EPA and North Carolina State University.107 Such plants use a complex sequence of processes and filters to remove or neutralize smokestack pollutants such as hydrochloric acid, sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, and heavy metals.108 “The hazardous elements are concentrated and carefully handled rather than dispersed as they would be in a landfill,” said Ivar Green-Paulsen, general manager of Denmark's largest waste-to-energy plant.109

Waste with a high percentage of organic material, such as food and agricultural waste, paper, wood, and sewage, can be biologically digested into renewable natural gas (RNG), which, in turn, can be used in logistics, manufacturing, and power production. For example, in 2015 UPS began using RNG at fueling depots in Sacramento, Fresno, and Los Angeles. The delivery company uses the equivalent of about 1.5 million gallons of RNG annually to fuel nearly 400 UPS compressed natural gas (CNG) vehicles in California110 and plans to use 500,000 gallons a year in Texas.111 According to the Bioenergy Association of California, the state has enough biomass waste to create RNG to replace three-quarters of the state's diesel needs.112

The previous three subsections illustrated ways of reducing environmental impact through the use of materials that would otherwise go to waste, be difficult to dispose of, or lead to environmental mishaps. Fly ash can be used to make cement, old Nike shoes can be used in Nike Grind, and hard-to-process waste can be used as an energy source. Nevertheless, in each of these cases (and many others), downcycling sparks complaints by environmentalists. For example, the downcycling examples of sneakers and jeans are lamented because they do nothing to reduce the impact of extracting virgin material for the manufacturing of new sneakers or jeans.

Such complaints might seem like perfectionist grumbling and another example of “the perfect is the enemy of the good” (see chapter 1). Alternatively, such criticisms may reflect fears that an interim solution will delay a long-term solution. A ton or so of fly ash may eliminate the need to emit a ton of CO2 in the making of concrete, but that ton of fly ash is associated with 20 to 30 tons of CO2 created in the burning of coal.113 “In one sense, yes, you're using up this waste material. In another way, it's justifying the burning of coal as a fuel source,” said Daniel Handeen, a research fellow at the University of Minnesota, Center for Sustainable Building Research.114

Environmentalists also criticize the burning of waste to produce energy. “Incinerators are really the devil,” said Laura Haight, a senior environmental associate with the New York Public Interest Research Group. “Once you build a waste-to-energy plant, you then have to feed it. Our priority is pushing for zero waste.”115

“We incinerate an enormous amount of waste in Denmark; waste which the Government could get much more out of by more recycling and better recycling,” said Ida Auken, Denmark's Minister for the Environment.116

Recycling also adds to the base of supply of raw materials, which reduces material costs, price volatility, and availability risks, according to an MIT study of platinum markets.117 Recycled materials suppliers provide a diffuse secondary source that is decoupled from the geopolitics of primary sources, such as in the case of the Chinese embargo on the export of rare earth elements and other cases of resource nationalism.118 Moreover, for many materials, recycling consumes less energy than does primary extraction and refinement. This can decouple the price of the material from the volatile price of energy. Finally, recycling shortens the duration of price spikes because in times of high demand and short primary supply, recyclers can more quickly increase recycling capacity than miners can increase primary supply.119

Some companies have made a business out of recycling high-value materials. In 2012, the Belgian chemical company Solvay Group opened two rare earth metals recycling plants in France, extracting the material from used light bulbs, batteries, and magnets.120 In 2013, the French company Veolia Environnement S.A. opened a recycling facility in Massachusetts to recover rare earth elements from phosphor powder, extracting it from fluorescent lamps, batteries, computers, electronics, and mercury-bearing waste.121

The downside of recycling as a business is that its economic viability is very sensitive to the cost of the virgin material. When oil prices plummeted in the second half of 2014, virgin plastic, which manufacturers prefer for technical reasons, became cheaper than recycled plastic and demand for recycled plastic plummeted. “People are just not willing to pay a higher price for the eco-friendly stuff,” said Anne Freer, director at plastic bottle maker Measom Freer. “We try to use as much recycled as possible, but it really comes down to price.”122 What had been a money-maker for municipalities and plastics recyclers became a money-loser, with plants and other assets underutilized.

“At US$50 oil, anyone that does just plastics recycling is out of business,” said David Steiner, chief executive of Waste Management Inc.123 “Many in the recycling industry are hanging by the skin of their teeth,” added Chris Collier, commercial director, CK Group, a plastics recycler.124 Two German recyclers and a large British one went bankrupt in 2015 and others, such as Waste Management, are cutting back on recycling investments. “The bottom line is that what is recycled and what is not is directly linked to oil,” said Tom Szaky, cofounder and CEO of TerraCycle Inc., which works with companies on recyclable packaging.125

In some cases, end-of-life materials retain so much value that they support the formation of natural markets for their collection, separation, and reprocessing. For example, copper is the world's most reusable resource, according to the Copper Development Association Inc.126 Relative to pure virgin copper smelted from mined ore, recycled copper retains 95 percent of its value because previous use and processing introduces only minor contamination.127 Nearly three-quarters of copper used in new products comes from recycled material. In fact, old copper is so valuable and easily recycled that thieves steal copper pipe and wire from vacant houses, as well as transmission wire from power stations. The US Department of Energy estimates that copper theft causes nearly $1 billion in losses to US businesses every year.128

Nonetheless, not all end-of-life products and postconsumer materials have sufficient value to justify collection and recycling based on financial criteria alone. Some materials have high collection costs, high separation costs, or a low value of the recycled material, which implies that natural recycling markets fail to form and end-of-life waste accumulates. If that waste poses an environmental threat, then governments may regulate the disposal of the product.

Whereas price cycles may create temporary downturns for companies involved in recycling, changes in product technology can create permanent disruptions. For some five decades, almost all televisions and computer monitors used cathode ray tubes (CRT) to display images. Given the technology at the time, the same lead-containing glass that shielded viewers from dangerous X-ray radiation made the glass tubes an environmental hazard. CRTs could contain up to eight pounds of lead in the tube.129 Due to lead's toxicity,130 the US EPA classified discarded CRTs as hazardous waste in the 1976 Resource Conservation and Recovery Act131—subjecting it to more stringent guidelines compared to other electronic waste. Initially, the Act was not a major burden because even as late as 2004, CRT processors could sell recycled CRT glass for as much as $200 per ton to firms producing new CRT televisions and monitors.

In the first decade of the 21st century, however, thin flat-panel displays rapidly replaced bulky CRTs in both the television and computer markets.132 That fast turnover in technology created a toxic waste challenge. As flat-screen displays began to dominate the market for televisions and monitors,133 CRT recycling grew more difficult, because the new displays did not use the leaded glass of CRTs. During the changeover, the EPA estimated that Americans discarded about 1.1 million tons of CRT televisions and monitors, of which fewer than 200,000 tons were recycled.134 By 2013, the same companies that had earned $200 per ton had to pay more than $200 per ton to dispose of the same material.135

In the absence of a market for recycled leaded glass, CRT-collecting companies resorted to stockpiling them. In 2012, a routine inquiry by two inspectors from California's Department of Toxic Substance Control discovered a warehouse the size of a football field filled nine feet high with unprocessed CRTs.136 In 2013, inspectors in Colorado and Arizona found similar scenes at abandoned warehouses that together contained more than 10,000 tons of CRTs and CRT glass.137 In September 2013, a report titled US CRT Glass Management estimated that roughly 330,000 tons of CRT glass remained in storage in American facilities.138

In response to this market failure, state regulators in the US took a page from the EU's regulatory doctrine of extended producer responsibility (EPR; see the section “You Made It, You Dispose of It!” earlier in this chapter). They made manufacturers of new displays shoulder the financial burden of recycling old displays.139 In Maine, for example, companies that handled discarded CRTs are asked to extract payments from the CRT's producer. According to the state's Title 38 law, “at a minimum, a consolidator shall invoice the manufacturers for the handling, transportation and recycling costs.”140 By 2013, in the absence of an overarching federal law, 22 US states had required technology manufacturers to pay for the cost of disposing their products—even when those products were sold long ago or by defunct competitors.141 The spirit of these US state laws was similar to the 1980 Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (see chapter 1). This law allowed the EPA to identify the corporate descendants of historical parties responsible for particularly polluted patches of industrial land and force them to pay cleanup costs.142 Such “after the fact” government actions are a version of EPR that is not grounded in law but rather in expediency. The potential for open-ended liability for environmental impacts discovered long after a product has reached end-of-life may induce companies toward more conservative eco-risk management initiatives such as the precautionary principle143 that new materials and technologies are presumed guilty of harm until proven innocent.

Sometimes, small things can create big problems, as is the case with the smallest of energy products: batteries. At the end of their life, batteries become an unfortunate combination of useless, worthless, and toxic. Batteries’ complex chemical ingredients can be difficult and costly to separate, and dumping them in landfills without any treatment can release toxic chemicals into the environment.144 Recycling batteries costs at least 10 times more than burying them in a landfill.145 Owing to the toxic nature of battery waste, many governments have regulated their disposal at the consumer level to force recycling. Despite the fact that California, for example, prohibits discarding batteries in household trash, Californians recycle less than 5 percent of the batteries they buy.146

The government of Belgium used the threat of a high eco-tax on new batteries to convince battery makers to collect and dispose of old ones.147 An 800-member nonprofit consortium of battery producers called Bebat148 handles battery collection and recycling. The program adds about 15 to 25 cents to the cost of each battery,149 but that cost is only about one-quarter the cost of the threatened eco-tax that battery makers would pay if they do not achieve the government's ever-increasing recycling rate targets. To achieve the required rate, Bebat installed bright green collection boxes at 24,000 locations in markets, photo shops, jewelers, schools, municipal locations, and elsewhere to offer convenient battery drop-off points for consumers.150,151 The consortium also paid for public information campaigns to ensure that the vast majority of consumers know about the recycling program.152 As of 2015, Belgians recycled an estimated 56 percent of batteries.153

Prior to World War II, most beverage containers were made of glass and were too valuable to discard. Instead, they were part of a closed-loop supply chain that returned empty bottles to the local brewery, local bottler, or milkman for cleaning and refilling. After the war, beverage companies, especially in the developed world, started transitioning to single-use bottles and cans. One beverage company even advertised, “Drink right from the can: No empties to return.”154

The Coca-Cola Company, after performing one of the first environmental LCAs in 1969, became more “comfortable” with the switch from glass bottles to plastic containers (see chapter 8).155 Low-cost mass production of the new containers eliminated the need for collecting, cleaning, and refilling of used containers. But the generated waste was a different story. The manufacturers’ interest in the disposable container ended as soon the customer purchased the drink, and the customer's interest in the container ended as soon as it was empty. Most consumers simply tossed their empties by the side of the road.

The resulting accumulation of litter so offended Vermont residents that, in 1953, the state instituted a four-year ban on nonrefillable beverage containers.156 After lobbying from the beer industry, the ban was allowed to expire, but legislators in Vermont and many other states still sought a solution. In 1972, Vermont was the first of 11 states157—followed closely by California, Michigan, and Oregon—to pass legislation that instituted deposits, thereby creating a financial incentive to collect and return the empties.158

The containers remained single-use, but sellers were forced to add a surcharge of a few cents more for each bottle or a can. The state collected the money and then paid it to any individual returning the container, thus creating a market for empty bottles and cans. Anyone could claim the deposit at collection and redemption centers, after which the containers were put into the recycling stream. In some cases, the poor and homeless collected the discarded containers to profit from the deposit. In other cases, wholesalers arose to collect the deposit and provide value added services to recycling plants.

On the whole, deposit mandates worked. Following the enactment of the mandates, 82 percent of covered beverage containers sold in the state of California were recycled in 1992.159 On average, the 10 states that require container deposits back to a store (California has thousands of special redemption locations) have glass container recycling rates of about 63 percent compared with a 24 percent recycling rate in non-deposit states, according to the Container Recycling Institute, which lobbies for such programs. Moreover, because the containers are kept separate from the rest of the waste stream, the contamination level of recyclables in deposit-collecting states is less of a problem.160

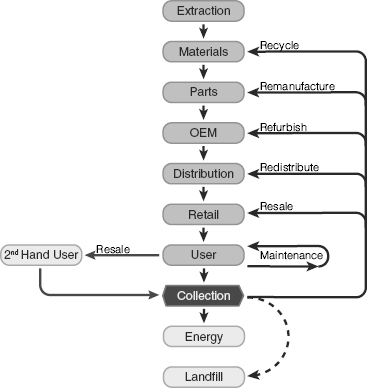

Environmentalists dream of “closing the loop”: recovering and recycling all the materials in the waste stream. Depicting the notion of the “circular economy,” figure 7.1 illustrates a stylized supply chain and the various “backwards paths” that a product or its constituent elements can take back into the supply chain.161

Figure 7.1 The circular economy

In theory, the perfect closed loop (coupled with zero population growth, no increases in per capita consumption, and no product innovation) would mean that production and sales of new goods would require no additional mining or harvesting of the Earth's natural resources. Nor would the economy add waste or pollution to landfills, waterways, or the air. All waste and postconsumer materials would cycle endlessly back to suppliers, manufacturers, and then on to the next generation of consumers. Under a closed-loop or circular economy, the concept of managing the “cradle-to-grave” supply chain would morph to “cradle-to-cradle.”

Johnson Controls International Plc, the world's largest supplier of automotive batteries, recycled its first battery in 1904—four years before Henry Ford introduced the Model T.162 By 2015, the company recycled more than 97 percent of the lead-acid automotive batteries it sold in North America. From each returned end-of-life battery, the company can efficiently recover 99 percent of the materials and make new lead-acid batteries containing 80 percent recycled materials.163

Johnson Controls, having no direct relationship with end users of batteries, developed close business ties with retailers, auto shops, and junkyards to obtain a constant supply of waste batteries. The company built a reverse logistics operation optimized to collect old batteries every time it delivered new ones.164 The company's reverse logistics and recycling systems are well established in North America, South America, and Europe (where it is known as ecosteps®), and the company is working to understand the economic and market conditions needed to implement or expand responsible recycling systems in other countries such as China.165

A key part of Johnson Controls’ closed-loop strategy is the recycling of not just the lead but also the other materials of the battery,166 thereby spreading the collection costs over more recycled elements. For example, Johnson Controls recycles the plastic housings of batteries to make new housings. It also recycles the acidic liquid electrolytes inside the battery and reuses them in new batteries or supplies them to makers of detergents and glass.

Sourcing 80 to 90 percent of its lead from recycled batteries protected the company from the volatility of lead prices on global markets. Between 2000 and 2010, lead prices oscillated between $500 per metric ton to as high as $4,000 per metric ton.167 The price of recycling is less volatile, even though it is also rising due to increasingly stricter environmental standards on secondary lead smelters. In fact, in 2012, Johnson Controls announced an 8 percent increase in the price of lead-acid batteries in North America, citing the investment required to meet these new regulations.168 At the same time, having a domestic supply of lead reduces the company's reliance on foreign lead producers such as China, Australia, and Peru,169 thereby also insulating Johnson Controls from currency exchange rate volatility.

Walmart aims to use three billion pounds of recycled plastic in the packaging and products it will sell by 2020 but is facing obstacles. “The problem is supply,” explained Rob Kaplan, director of product sustainability at Walmart.170 Similarly, Coca-Cola had a 2015 goal of using at least 25 percent recycled plastics in its containers, but scarce supply and high costs forced a downward revision of the goal. Much of the constrained supply of postconsumer plastic comes from municipal waste streams, which are an underdeveloped tier in the supplier base of the circular economy. Municipal waste collection is so diffuse and fragmented that neither Walmart nor Coca-Cola by themselves can readily remake the waste collection industry.

To encourage the growth of municipal recycling supply chains, a consortium of nine companies, including Walmart, Coca-Cola, P&G, and Goldman Sachs, created the $100 million Closed Loop Fund.171 The Fund offers zero-interest rate loans to municipalities and private entities to develop more recycling infrastructure and services. These loans help waste-stream collectors and processors reduce the fraction of materials sent to landfill (thus reducing the amount they pay in landfill fees) and to add revenues from the sale of recycled raw materials. At the same time, the resultant increased supply of recycled raw material would enable the consortium companies to offer more products with recycled content.172

In another example of a direct partnership, Kimberly Clark Brazil collaborated with the mayor's office of Suzano, Brazil, to engage waste pickers.173 The company provided training for local waste collectors and installed an extrusion machine that makes plastic sheets out of collected recycled material. The sheets are used in many different business applications, including the construction of garbage-collecting stations for Carrefour. According to Kimberly Clark's 2010 Sustainability Report, “This program demonstrates the feasibility of a solid waste reverse logistics system that is socially appealing and offers lower costs to the supply chain. All parties become responsible for the post-consumption stage through this system, which removes waste from the environment and channels it toward an environmentally sound destination.”174

The Dutch port of Rotterdam plans to become a major European hub for closing the loop on one of the primary culprits of climate change: carbon dioxide. In 2007, the Municipality of Rotterdam, the Port of Rotterdam Authority, the Rijnmond central environmental service agency, DCMR,175 and the port business association, Deltalinqs, founded the Rotterdam Climate Initiative (RCI).176 Building on the industrial and logistics cluster around Rotterdam, RCI aims to develop an integrated supply chain of CO2 producers, CO2 customers, and storage facilities, all interlinked by pipes, barges, and oceangoing ships. Ultimately, RCI seeks to turn Rotterdam into a hub that collects CO2 from Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Antwerp, the Ruhr Valley of Germany, and many other Northern European sources of CO2 and supplies the gas to a variety of CO2 applications and sequestration facilities.177

For example, Dutch greenhouse operators routinely burn natural gas to generate CO2, which increases the growth rate and yield of plants in greenhouses.178 One of Rotterdam's early projects captured CO2 from a power plant, oil refinery, and a bioethanol plant and then sold the CO2 to greenhouse operators north of Rotterdam.179 This project also reused an abandoned oil pipeline that happened to pass through the greenhouse agriculture areas in the Westlands of Holland.180 As of 2011, the project supplied CO2 to one-third of the area's greenhouses and is looking to expand the number of CO2 suppliers.

To manage the CO2 hub, Rotterdam is developing logistics infrastructure, including backbone pipelines and portside CO2 loading facilities that will enable ships or offshore pipelines to take CO2 to remote sequestration or application sites.181 These remote applications include the use of captured CO2 to aid in the extraction of more fossil fuels. Called enhanced oil recovery, it involves injecting CO2 into an oil field reservoir, which drives the oil to the collection well and increases both the short-term extraction rate and the long-term percentage of the total reservoir that can be recovered.182 Any CO2 that comes back up with the oil can be recycled back to the injection site.183

It seems fitting that among the best places to sequester CO2 are the same deep, impermeable rock formations that locked natural gas and oil underground for tens of millions of years.184 “Of course, you need to pick sites carefully,” said Sally Benson, Stanford professor of energy resources engineering and director of Stanford's Global Climate and Energy Project. “But finding these kinds of locations does not seem infeasible.”185

Companies who want to close the loop in order to gain access to secondary sources of raw material, respond to EPR regulatory trends, develop a deeper relationship with the end customer, or for purposes of reducing their environmental impacts face certain limits of closed-loop systems. Although making new products from materials recovered from old products seems simple in theory, many practical obstacles stymie full circularity. For example, the average mobile phone contains $16 worth of high-value metals such as gold, silver, and palladium, but current smelter-based recycling processes can only recover $3 worth of these ingredients.186

In some cases, contamination or impurities in the waste materials limits recycling.187,188 Municipal waste streams, especially, often come with contamination problems that limit the value of recovered materials. “We get soiled diapers and dead animals on the line,” complained James Devlin of North Carolina recycling facility operator ReCommunity.189 For some clear plastics, contamination levels of only 0.0025 percent to 0.1 percent can create hazing of the recycled material.190 Even for relatively uncontaminated materials such as scrap aluminum, purity is an issue, with different aluminum alloys acting like contaminants for other alloys. The result is aluminum makers must either dilute the recycled metal with virgin metal, which prevents complete circularity; use downcycling, in which higher grades of aluminum (e.g., aircraft and electronic parts) are recycled into lower grades (e.g., engine blocks); or pay for more expensive recycling processes to physically segregate alloys or chemically remove the impurities.191

Sometimes green tactics can have negative consequences elsewhere in the supply chain and impede circularity. For example, lighter-weight bottles, which reduce material use and other environmental impacts, can fool some recyclers’ separation systems, which were designed on the assumption that plastic bottles are heavier than paper and cardboard packaging. Some new sustainable plastics, such as bio-derived polylactic acid (PLA), are not recyclable at all with current technology. Recycling creates environmental impacts, too. Ironically, reusing glass bottles makes Coca-Cola's water footprint worse in the developing world, where refillable glass bottles make up a large percentage of the volume, because carefully cleaning those returned bottles demands large amounts of water.192

Recycling also faces social and regulatory challenges. Cultural and social norms sometimes create barriers in the form of consumer habits, market resistance, and transaction frictions in getting discarded goods to a pickup point and recycling center. As mentioned earlier, the Japanese recycle 77 percent of their plastic waste, whereas Americans only recycle 20 percent of their plastic.193 Regulatory policies might also have unexpected (and unintended) consequences on recycling. For example, the US Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) creates a compliance burden that discourages companies from attempting to recycle electronic waste.194

In other cases, unrelated regulations may interfere with closed-loop recycling. “We have looked in detail at the circular economy, and will continue to do so, but sometimes it feels like loops for loops’ sake and in this instance, there may not be a loop,” said Tim Brooks, LEGO's senior director of environmental sustainability.195 On paper, LEGO's toy bricks seem like a perfect product for developing a closed loop system. The bricks are mostly made of a single material: ABS (acrylonitrile butadiene styrene) thermoplastic. In addition, LEGO bricks are abundant, with an average of 90 bricks per person on the planet, and they are also durable. But the toy industry is highly regulated with stringent health and safety issues that make the use of recycled material very limited.

Recycling—even closed-loop recycling—can't eliminate all environmental impacts. Many of the challenges with both the material footprints of new products and the economics of recovering materials from end-of-life products stem from decisions made during product design. Careful design and engineering can further reduce environmental impacts in the sourcing, making, and delivery processes, as well as reduce impacts when the product is ultimately being used by consumers.