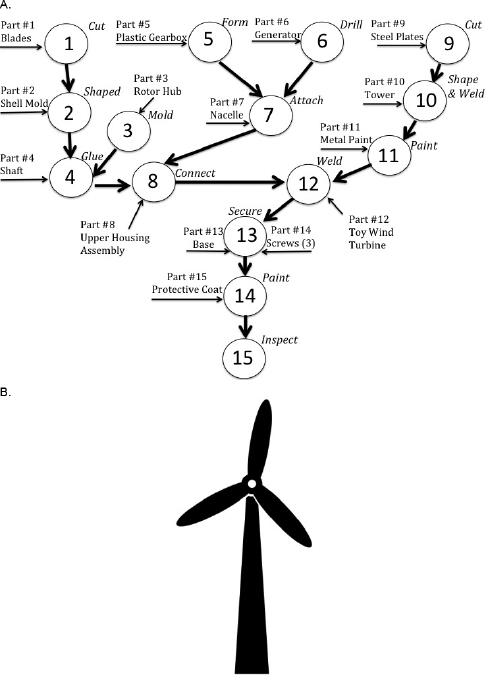

Figure 2.1 Toy wind turbine and its bill of materials

Greenpeace's attack on Nestlé for the use of palm oil in KitKat bars highlights a nearly universal characteristic of modern business: companies’ heavy reliance on long supply chains that contain vast networks of suppliers of raw materials, refined ingredients, parts, and subassemblies. The term supply chain refers to a figurative linear chain of companies that extract raw materials, refine them, make parts, and assemble them into finished goods that are delivered to customers or distributed to retailers’ shelves where they eventually make their way into consumers’ homes. It also includes a vast array of intermediaries and service providers who move and store the material as well as handle the money and information involved.

In Nestlé's case, the company buys palm oil from a distributor who buys it from a refiner who buys crude palm oil from a mill who buys palm fruit from a middleman who in turn buys it from a plantation. The plantations that potentially create the environmental impacts sit deep within the palm oil supply chains.

The image of a neat chain of companies grossly oversimplifies the actual situation. Supply chains are actually networks, branching in many directions that include the many contributing upstream suppliers of any given ingredient and the many different downstream customers that rely on that same ingredient. For example, 40 percent of the palm oil in Indonesia comes from small farms.1 Hundreds of thousands of palm fruit producers of all sizes send truckloads of palm fruit to palm oil mills that extract both the reddish palm fruit oil and the pale yellow palm kernel oil. Next, palm oil refineries remove impurities (degumming, bleaching, and deodorizing) and separate the different fatty acid components in the raw oil for various applications. The Palm Oil Refiners Association of Malaysia defines 14 different standardized palm oil products.2 The various refined palm oil products then go to ingredient makers that produce edible oils and fats, saponified oils for soap, esterified oils for biodiesel, and dozens of other derivative products.

At each stage, middlemen might aggregate and mix sources of supply, accumulate inventories awaiting buyers, sell portions of their stocks, or transport bulk quantities to remote points of demand. Incoming oil flows into huge bulk tanks, commingling with prior batches before being sent to the next tier. With each stage, the location of the original palm oil plantation becomes less and less traceable, as oil from many plantations mixes together. By the time palm oil reaches Nestlé, almost any palm oil plantation in the world may have contributed to that particular batch. The complexity of the palm oil supply chain was a key reason Nestlé had trouble responding effectively to Greenpeace's attack.

Moreover, the KitKat product alone has 15 ingredients on the label,3 which means Nestle has many distinct supply chains that provide chocolate, wheat flour, milk and milk by-products, vegetable fats, and other trace ingredients. Additionally, the vegetable fat in a KitKat might include any of seven different kinds of fat: palm kernel, palm fruit, shea, illipe, mango kernel, kokum gurgi, or sal. Even the plastic wrappers and cardboard boxes used for packaging the snack come from respective supply chains that trace back to oil wells and forests.

Almost every product has a complex interlinked supply network of contributing companies that spans the miners, growers, suppliers, manufacturing plants, transportation, warehouses, distribution, retailers, and the myriad supporting companies involved in the design, procurement, manufacturing, storing, shipping, selling, tracking, payments, customs, and servicing of goods. Many other raw materials (e.g., fossil fuels, wood products, conflict minerals, natural fibers, grains, tea, coffee, and cocoa) are aggregated from many sources as they are bought, processed, and sold on world markets. In the case of soap makers, the supply chain is even more opaque. Sodium lauryl sulfate, a common cleansing ingredient in soap as well as shampoo and toothpaste, can be made from palm kernel oil, coconut oil, petroleum, or a range of other oils.4 Thus, buyers of this and similar ingredients may not even know whether the material was made from highly contentious palm oil, less contentious coconut oil, high-carbon-footprint petroleum, or another oil entirely.

Despite the oversimplification, the notion of a supply chain helps businesses think about management and sustainability in two ways. First, it reflects the general progression from raw materials to finished goods that occurs with accumulating environmental footprints and impacts along the chain, as more is done to the materials by more people in more places. Second, it highlights the idea of suppliers being a source of material and parts for manufacturers who make products and deliver them to their customers. At that level, the network is like a chain in that suppliers may have further suppliers up the chain and customers may have further customers down the chain. (The view of suppliers “upstream” and customers “downstream” is rooted in the riverlike direction of the flow of material, parts, and goods.) Each of these tiers of companies in the chain contributes to the total environmental impact of the product or service delivered to the final consumer.

To help firms design their internal business processes across different products, geographies, and networks, the Supply Chain Council (SCC) developed the Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) model. The model, on its 11th version in 2013, classifies activities within each supply chain into one of six distinct high level (or “level-1”) processes: Plan, Source, Make, Deliver, Return, and Enable.5,6 Plan and Enable cover all the tasks of managing the business and the other four high-level processes. Source refers to the processes of procuring materials and parts from the upstream supply chain that go into the finished product. Make is the manufacturing process of converting sourced materials into finished goods. Deliver covers the downstream supply chain activities of warehousing, distribution, and transportation that fulfill customer orders. Return includes processes for handling defective products, repairs, and unwanted products.

Much of the environmental impact of any product depends both on what it is made of, and on how it is made. The “Make” process is the step in which a product's constituent parts are converted into finished goods via a series of manufacturing operations.

Imagine a small, toy wind turbine—the child's version of the massive winds turbines such as those built by Siemens that are sprouting across the landscapes in many countries. The first step in understanding the environmental impact of making this toy is to analyze its bill of materials (BOM), which lists all the parts and the quantities of those parts required to manufacture a unit of the product. The BOM also includes information about how the parts relate to each other in terms of assemblies and subassemblies. Figure 2.1 depicts a 15-step process map with the 15 numbered parts listed in the toy's BOM and the respective manufacturing processes required to make the toy. Each part in the BOM is made using material, energy, and water; the process may also involve waste and emissions, thus accruing environmental impacts. A company's own manufacturing processes that make and assemble parts into a finished product will add to the total impacts accumulated along the supply chain.

Figure 2.1 Toy wind turbine and its bill of materials

This toy wind turbine has three major assemblies: the blade assembly, the nacelle assembly (the top portion that connects the tower to the blades), and the tower assembly. Workers start by making the three wooden blades (Part 1), which they first cut to the right size (Process 1) and then shape (Process 2) into shell molds (Part 2). They mold the rotor hub (Part 3) and combine the hub, blades, and shaft (Part 4) to make the blade assembly. A second group of workers creates the nacelle assembly by forming the plastic gearbox (Part 5), drilling mounting holes in the generator (Part 6), and attaching the parts together. They then combine the blade assembly and nacelle (Part 7) to create the upper housing assembly (Part 8).

Meanwhile, a third group of workers builds the tiny tower for the toy by cutting steel plates (Part 9), welding them together into the tower (Part 10), and applying a coat of metal paint (Part 11). They weld the upper housing to the top of the tower to make the toy (Part 12). Finally, they use three screws (Part 14) to secure the toy to its base (Part 13). A final protective coating of more paint (Part 15) produces the completed toy, which inspectors then check for quality.

In theory, the BOM lists all the parts and materials bought from suppliers or made within the factory that go into a product. Yet BOMs actually leave out many of the incidental materials consumed or handled during the process of making a product. These indirect materials include an array of manufacturing consumables such as lubricants, solvents, cleansers, filters, and other materials that lurk in the factory's supply closet and are used in making products, even if the products are not made from these supplies.

From an environmental perspective, the two biggest categories of materials not listed in a BOM are energy and water. Manufacturing processes consume electricity for machinery, lighting, heating, and cooling. Some processes may consume fuels, such as the acetylene gas used to flame-cut the wind turbine tower parts, natural gas to generate hot water, or propane to power the factory's forklifts. The factory might use many gallons of water to wash parts, chemically treat parts, or cool industrial processes.

Thus, the BOM gives only a partial basis for calculating the environmental impacts of manufacturing. Although it implicitly specifies a unit of output of the finished product, it does not document other manufacturing outputs. Each item of the BOM, as well as indirect materials, might come with greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, wastewater, and other by-products. Some manufacturing steps, such as painting or gluing, may give off toxic or smog-inducing vapors.

In the 1920s, Ford's River Rouge plant was famous for owning and managing the entire car-making process. Raw materials straight from the earth went in one end of the sprawling factory complex, and finished automobiles rolled out the other end. The company owned iron mines, limestone quarries, coal mines, rubber plantations, and forests. Ford owned a fleet of barges and a railroad to ship materials from its mines to its plant. The company brought its iron ore, limestone, and coal to River Rouge to smelt into its own iron and steel. Ford brought sand to make glass and raw rubber to make tires. Ford even had its own electrical power plant on site to supply the factory and its 100,000 workers. Ford's 1920s strategy is known as vertical integration, in which a company strives to own many or all of the stages of production (and sometimes logistics and other services) throughout its supply chain. Had the environment been a concern when River Rouge was in operation, Ford could have documented the impacts of its entire process, including the 5,500 tons of coal burned every day, or the 538 million gallons of water used each day.7,8,9

The opposite of vertical integration is outsourcing—the use of outside suppliers for component items and services, even those the company had previously made and had the assets and know-how to make. Although Ford's goal with River Rouge was self-sufficiency, the factory still depended on no fewer than 6,000 outside suppliers for many specialized materials, components, and supplies.10 Ford sometimes outsourced to supplement its own capacity. For example, Ford pioneered the use of soybeans in industrial products: By 1935, 60 pounds of soybeans went into the paint and molded plastic of each Ford car. The company eventually owned 60,000 acres of soybean farms, but these farms could supply only a fraction of all the soybeans needed. Thus, Ford bought the bulk of this raw material from outside growers.11

Over the decades, Ford moved away from vertical integration, outsourcing more and more production of raw materials and intermediate parts to outside suppliers. The biggest reason for outsourcing is to get the most competitive components and materials possible from specialized suppliers with economies of scale and special know-how in their respective industries. For example, carmakers spun off their internal parts-making divisions, such as Ford's Visteon and GM's Delphi, with the intention that these divisions would become more competitive and have better scale if they were exposed to market forces and sold parts to other companies.

By the dawn of the 21st century, outsourcing had become the norm as most companies focused on their “core competencies” and outsourced other functions. Still, some companies outsource less than others. For example, Samsung makes many of the parts—such as processors, memory chips, camera chips, and displays12—for the televisions, smartphones, and computer products it assembles. Cisco, by contrast, makes none of the parts that go into its many products. In fact, Cisco, and many other technology firms, such as Apple and Microsoft, as well as apparel companies such as Christian Dior and Nike, outsource virtually 100 percent of their manufacturing and then buy the finished goods in retail packaging from contract manufacturers. These highly outsourced companies typically only handle the design, marketing, sales, and supply chain management of their products.

Outsourcing brings the advantage of greater flexibility in choosing suppliers to meet changing volume and technology requirements, but also a disadvantage in that companies have lower visibility into, and control over, the processes deployed by those suppliers (and, in turn, their suppliers). The environmental impacts of outsourced manufacturing lie in the hands of suppliers.

The traditional criteria that most companies use in choosing suppliers include: (i) the quality of the part, materials, or services and the supplier's commitment to innovation; (ii) the full (“landed”) cost of the items or service; (iii) the supplier's capacity to serve the volume required by the company; and (iv) the lead time for the order and the supplier's responsiveness.

As shown in chapter 1, however, a supplier's deficient environmental practices can negatively impact a company. Consequently, companies have begun to assess the environmental practices of suppliers or prohibit particular practices (see chapter 5). Yet, managing the environmental impacts of suppliers can be challenging as the suppliers, in turn, have their own suppliers, and those have their own suppliers, and so on up the chain. In many cases—and not only for high-tech brand names—the lion's share of a product's environmental impacts take place deep within the supply chain at the mines, farms, and oil fields that produce raw materials.

Unless the wind turbine toy maker is vertically integrated, each of the toy's parts will have come from one or more suppliers with respective environmental impacts. For example, the wood for the blades may have come from a sustainable tree farm or from an illegal clear-cut of old-growth forest. The steel for the tower may be recycled steel (low-impact) or virgin steel made from iron ore (high-impact). As these suppliers perform their own source, make, and deliver processes on their parts, they incur environmental impacts that accrue to the final product. Some suppliers might be in regions powered by coal-fired generators while others might rely on hydroelectric power, thereby affecting the carbon footprint of the electricity used by the supplier. Suppliers’ physical locations may also affect land-use patterns, water availability, and legal regimes.

In contrast to the simple toy wind turbine with its 15 parts, a full-sized Siemens AG wind-turbine contains more than 8,000 parts13 coming from manufacturers in at least six distinct industries operating in 177 countries.14 Construction of the Siemens’ turbine blades alone requires 50 to 60 suppliers and four or five principal steps.15 Wind turbine manufacturing relies on supply chains that deliver a wide range of metals, polymers, and other materials, as well as electromechanical, electrical, semiconductor, and other types of parts. The turbines even contain agricultural products: plantation-grown balsa wood forms the lightweight core of each of the massive blades.

The 400 suppliers that ship parts directly to Siemens’ wind turbine division are known as Tier 1 suppliers. Siemens selects all of its Tier 1 suppliers and negotiates contracts with them. These contracts formalize the delivered component's specifications, delivery terms, invoicing and payment terms, penalties, intellectual property provisions, reporting obligations, codes of conduct, and so on.

Tier 1 suppliers are often large- or medium-size organizations themselves. For example, one of Siemens’ Tier 1 suppliers is Weidmüller, a 160-year old company that produces and sells €630 million of electrical and electronics components each year.16 Weidmüller alone delivers more than three billion parts every year to its 24,000 customers, including Siemens. The supplier operates seven production sites with 4,600 employees around the world.17

Each of Weidmüller's parts has its own BOM, too. Like Siemens, Weidmüller also has a network of Tier 1 suppliers, with contracts specifying product and quality specifications, payment terms, intellectual property, and codes of conduct. Weidmüller's Tier 1 suppliers are referred to as “Tier 2” suppliers of Siemens, indicating the greater commercial distance between Siemens’ and Weidmüller's direct suppliers. In the case of Siemens’ wind turbines, the 400 Tier 1 suppliers have 3,000 suppliers who are Tier 2 to Siemens.18 Direct suppliers to Siemens’ Tier 2 suppliers are Tier 3 suppliers of Siemens. For products as complex as a Siemens wind turbine, there may be Tier 4, Tier 5, Tier 6 suppliers and even further, before reaching basic raw materials extracted from mines, oil wells, farms, and oceans. As the supply chain distance extends from the original equipment maker to the deeper tiers of suppliers, companies typically do not even know the identity of these deep-tier suppliers or the country of origin of the raw materials.

Moreover, Siemens also produces many other products, ranging from factory automation, building technology and medical devices to consumer products. In total, the company employs 370,000 people and does business in 190 countries around the world.19 Its multiple supply chains across all its products span more than 90,000 Tier 1 suppliers and countless deep-tier suppliers.20

As companies, product offerings, and BOMs grow in size and complexity, it is not uncommon for a supplier to be both a Tier 1 and a Tier 2 supplier for the same manufacturer, sometimes unbeknownst to both of them. In addition, large companies in the same industry often buy from and sell to each other, serving as both supplier and customer to each other. For example, Siemens might buy industrial products from a supplier whose factory uses Siemens’ factory-automation products. These hidden deep supply chain relationships typically cause no problems until disaster strikes.

On April 24, 2013, horrific images saturated news outlets as more than 1,100 bodies were pulled from the collapsed eight-story Rana Plaza garment factory in Bangladesh.21 Muhammad Yunus, the Bangladeshi Nobel laureate, wrote that the disaster was “a symbol of our failure as a nation.”22 Rana Plaza was not an isolated incident. Six months before this disaster, a fire at a different Bangladeshi garment factory, which was owned by Tazreen Fashions, killed 112 workers.23 Such events in Bangladesh put a tragic human face on the repugnant conditions deep within some companies’ outsourced global supply chains.

Paralleling the gruesome search for bodies buried under the rubble of Rana Plaza was the search for the Western companies behind the orders for the garments made in the collapsed factory. Most companies denied using suppliers who were operating in the structurally unsound building where employees were forced to work even after large cracks had appeared in the walls the previous day. Despite those denials, recovery workers found apparel in the rubble that had been ordered by many major retailers, including J. C. Penney and Walmart.

J. C. Penney, for its part, claimed that the company had no direct connection to any of the building's tenants. Yet Daphne Avila, a J. C. Penney spokeswoman, admitted the company did not “have visibility into our national brand partners’ supplier bases,” and that problem prevented the retailer from knowing more about where the clothes were being made. “This is something that we're actively working on,” she added.24

In contrast, Walmart believed it had visibility and control over its supply chain. Walmart had fired Canadian jeans supplier Fame Jeans after it uncovered evidence that the supplier had ordered pants from one of the Rana Plaza factories in 2012, in violation of Walmart's policies. A Walmart spokesperson said, “This supplier, Fame Jeans, had told us there was no previous production at Rana Plaza … our suppliers have a binding obligation to disclose all factories producing Walmart merchandise.”25 Similarly, in the case of the Tazreen factory fire, Walmart had banned Tazreen Fashions from its approved supplier list after auditors hired by Walmart inspected the factory and declared Tazreen to be “high risk.”26 However, one of Walmart's other authorized suppliers subcontracted with another authorized supplier and then that subcontractor shifted the work to Tazreen.27 Walmart terminated its relationships with that supplier, too. Ultimately, name-brand companies such as Benetton, Mango, Bonmarché, Primark, The Children's Place, and others acknowledged their current or past use of the suppliers operating in the collapsed structure.28 Nor was worker safety the only social concern in Bangladesh. When Pope Francis learned that Bangladesh's minimum wage was only $40 per month, he said, “This is called slave labor.”29

In mid-2007, in the wake of recalls hitting another toy maker, regulators lauded Mattel Inc.'s supplier control. “There are companies that live up to their obligations to the government as well as to consumers, and they are one of them,” said the US government's Consumer Product Safety Commission spokeswomen Julie Vallese in reference to Mattel.30 But even if a company takes steps to control deep-tier suppliers, supply chains are dynamic in nature, putting compliance at risk.

In early July 2007, testing by a European retailer revealed prohibited levels of lead in the paint and coatings on some Mattel toys. Mattel immediately halted production of the toys, investigated the cause, confirmed the problem, and announced a recall of nearly one million toys of 83 different types in early August 2007.31 Subsequent testing found other lead-contaminated toys, which forced Mattel to recall another million toys that autumn.32 The company also paid a $2.3 million fine for violating federal bans on lead paint.33 More importantly, the incident tainted the brand in the eyes of consumers and the media, causing a 25 percent drop in the value of its stock during the worst of the recall incident.34

The fault occurred deep in Mattel's supply chain. A long-time paint supplier to the company's Chinese contract manufacturer had run short of the paint's colorants, quickly found a backup supplier via the Internet, and used that unauthorized source based on fraudulent certifications that the colorant was lead-free. The paint supplier did not test the new colorant because testing would have delayed production. Workers, however, noted that the new paint smelled different from the usual formulation.35 “This is a vendor plant with whom we've worked for 15 years; this isn't somebody that just started making toys for us,” Robert A. Eckert, CEO of Mattel, said in an interview. “They understand our regulations, they understand our program, and something went wrong. That hurts.”36

The deep and interlinked structure of supply chains can lead to widespread contamination incidents. In October 2004, a routine test of the milk at a Dutch farm revealed high levels of dioxin, a dangerous and tightly regulated chemical. Dioxin is considered so toxic that a single gram of it is sufficient to contaminate 14 million liters of milk above EU safety limits.37

Initially, the authorities suspected a faulty furnace to be the cause—fire can create these substances—but further investigation finally uncovered the true, distant cause: the cow feed.38 Specifically, the investigation revealed that in August 2004, McCain Food Limited's potato processing plant in Holland had received a load of marly clay from a German clay mine. Unbeknownst to both the clay company and the potato processing company, the clay had been contaminated with dioxin, which can occur naturally in some kinds of clay. McCain's plant made a watery slurry with the clay and used it to separate low-quality potatoes (which float in the muddy mixture) from denser, high-quality potatoes. Ironically, the reason McCain began using clay in the separation process was that a previous salt-water process had been outlawed for environmental reasons.39 Fortunately, the dioxin did not contaminate the processed potatoes, which were used to make French fries and other snacks. Unfortunately, the dioxin did contaminate the potato peels that were converted into animal feed.

If most companies have many suppliers, most suppliers have many customers, too. Auspiciously, the EU's food traceability rules include a “one step forward and one step back” provision for all human food and animal feed companies.40 Authorities traced the contaminated peels to animal food processors in the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and Germany, and then traced the tainted feed to more than 200 farms.41 Rapid detection and tracing in both directions prevented any dioxin-tainted milk from reaching consumers.42 Yet detecting the contamination after the fact was cold comfort to the farmers who were forced to destroy milk or animals.

Many agricultural commodities such as palm oil, bananas, coffee, and cocoa grow only under specific conditions in a limited number of countries. Other agricultural commodities (e.g., grains, soybeans, cotton, livestock, and wood) may have a broader geographic range but still depend on adequate local water and fertilizers. Similarly, many economically important minerals, such as rare earths, platinum group metals, tantalum, and graphite can be found only in a limited number of sites.43 Many of these regions face intense social and economic tensions between preserving land for wildlife and biodiversity on the one hand, or developing the land for production, such as agriculture or mining, on the other. Thus, the starting points of many supply chains—the raw materials producers—are strongly tied to geography.

In contrast, businesses downstream in the supply chain have more freedom to choose geographic locations for manufacturing and distribution operations. Companies may choose to locate production facilities close to raw material supplies (e.g., a smelter near a mine); close to sources of labor (e.g., low-cost or high-skill regions); close to centers of demand (e.g., major population centers); in an industrial cluster location (close to other similar manufacturers); or in a location influenced by government (e.g., owing to incentives and regulations). Although companies make these decisions on either economic grounds (e.g., costs of land, labor, local materials, and transportation) or strategic grounds (e.g., to open new markets or create economies of scale), the decisions also have environmental effects.

Countries vary widely in their base level of environmental stewardship, which can reflect well or poorly on companies with operations or suppliers in those countries. The Environmental Performance Index44 is an independent measure of environmental sustainability at the country level. It was created by the Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy and Columbia University's Center for International Earth Science Information Network, in collaboration with the World Economic Forum. The index measures both protection of human health and protection of the ecosystem. The former considers measurable health impacts, air quality, water cleanliness, and sanitation. The latter considers impacts on carbon footprint, agriculture, forests, water, fisheries, and biodiversity.45 The 20 index indicators include both regulatory factors (e.g., pesticide regulations and habitat protection) and environmental outcomes (e.g., changes in forest cover and air quality). The index organizers rank countries and provide 10-year trend data. The 2016 report46 ranked Finland first, followed by Iceland and Sweden, with the United States checking in at 26th place, Germany in 30th, and China lagging behind in 109th place.

A single part, such as the 75-meter-long blade of a Siemens wind turbine, can travel thousands or even tens of thousands of miles on its journey from raw materials to installation. The blades begin as 15- to 30-meter-tall balsa trees in Ecuador, planted four to six years in advance.47 After the trees are cut, the lumber is processed in several steps. It must be cut, grooved, tiled, assembled into a blade shape, and then coated with layers of plastic netting. Eventually, it arrives at one of Siemens’ four blade facilities in Europe, India, or Thailand. The semi-finished blade may make an additional trip to Spain, Finland, or the United States, depending on the final customer location, manufacturing capacity, and project timeline. Finally, the finished blade is transported to the installation site, which could be almost anywhere in the world.

Whereas the early parts of the journey can utilize standard trucks, rail cars, and shipping containers, the last steps of the journey rely on more specialized transportation. Each installation-ready blade can stretch as long as 75 meters (246 feet).48 The loading, unloading, and transporting of individual blades is a logistical challenge that requires cranes, heavy tools, and specialized trucks that test the limits of road-based transport.49 On every step of the journey, fuel goes into a tank, is burned in an engine, and GHGs and other emissions come out of an exhaust pipe.

In the rush before Christmas, a toymaker might experience a surge in demand if its model wind turbine becomes the season's must-have toy. These last-minute orders mean the toymaker must suddenly order more parts from suppliers, get those parts, make more toys, and ship the toys to stores before the holiday. If the toymaker and its suppliers get enough warning, they can use ocean freight or rail transportation to deliver their wares efficiently around the world or across the country. Last-minute orders, however, provoke a flurry of warehousing and transportation activities. If time is short, the toymaker will switch to air freight when the toys “absolutely, positively have to get there overnight” (as the FedEx motto declares).

The rapidly declining costs of communications and the growing efficiency of logistics are enabling global trade and long supply chains. Overall, trade-related freight transportation accounts for more than 7 percent of all GHG emissions worldwide.50 However, the total amount of transportation may be less indicative of environmental impact than how goods are transported. For example, airfreight emits more than 100 times the GHGs (in grams per ton-mile) than ocean freight.51 The same amount of fuel needed to fly 150 tons of airfreight 5,000 miles at 570 mph can push 48,000 tons of ocean freight that same distance on a modern vessel at 22 mph.52

Although it's easy to tally the fuel burned by a vehicle making a delivery, this may represent only half the footprint because of the need to reposition the conveyance. If a truck makes a trip from a supplier to a manufacturer fully loaded but then drives back to the supplier empty, the total footprint is almost double that of the one-way journey due to these “empty miles.” Companies can reduce both the cost and footprint of a delivery by finding what is called a “backhaul load,” in which the vehicle returns to its origin or another pickup point while carrying revenue-paying cargo. In that case, the emissions of the backhaul will be counted as part of the backhaul shipment.

The overall pattern of freight flows makes empty miles almost unavoidable. In most cases, more tons of materials are shipped from mines and farms than to mines and farms. Similarly, at most retail locations, trucks arrive full of goods and depart empty. Furthermore, in some cases the total weight of the flow in and out of a certain region is balanced but the modes used are not. For example, although most products are delivered to southern Florida by truck, most northbound freight from Florida (be it Florida's agricultural products or imports coming from the Port of Miami) move by rail. The result is empty miles for trucks returning north and empty container movements on the rails going south. Chapter 7 delves into this issue in further detail.

At the same time that materials flow down the supply chain, money generally flows up the chain when consumers pay the retailer, the retailer pays the distributor, the distributor pays the manufacturer, the manufacturer pays its suppliers, and so on through to the factory workers, farmers, or miners. This money flow—and its equitability and consistency—contribute to the welfare of the workers and communities at the heart of all supply chains. The Fair Trade movement seeks to ensure that all workers, especially those in developing countries, share in the bounty of the modern global economy.53 The movement advocates for improved social and environmental standards through higher payments to workers and farmers for their labor and produce.

Another key supply chain flow is information in the form of forecasts, purchase orders, shipping notices, invoices, and other business and operational data. Information flows in both directions to coordinate activities across the supply chain. As shown in chapters 3, 5, and 9, these information flows play a major role in measuring and managing environmental sustainability.

Supply chain managers typically strive for both operational and strategic visibility. Operational visibility includes knowing where parts and products are as they move through the supply chain or wait as inventory in warehouses. Managers use these data to detect operational problems, manage the execution of plans, and handle supply and demand fluctuations. Strategic visibility includes knowledge of the multiyear capacity and technology road maps of the supply base. It is used to make long-term product, service, and supply network choices. Sustainability, in contrast, calls for environmental visibility—understanding all the suppliers, including deep-tier ones, who are involved in providing the goods and services required to make a product—as well as the environmental impacts of these supplied products and services. Companies use environmental visibility to assess (see chapter 3) and manage impacts. Environmental visibility also enables transparency, which is the ability to show outsiders—including downstream companies, certification bodies, NGOs, governments, sustainability-minded consumers, and investors—how the company is managing environmental impacts and risks. Transparency means that companies and consumers can access relevant information throughout the supply chain and know who makes and handles products and parts and how they are made, stored, transported, and handled.

Even the most fuel-efficient cars can emit more than three times the carbon during their driving lifetime after they leave the factory than what was emitted during the manufacture of those cars.54 Many types of products have significant environmental impacts during the use phase of their lives. The use phase consists of all the customer's activities and processes associated with the use of a company's products and services. The most obvious of these are energy-consuming products such as vehicles, appliances, HVAC (heating, ventilation, and cooling) equipment, and computers. Less obvious are products, such as shampoos, detergents, and cleansers that involve the use of hot water and consume both energy and water, as well as contaminate that water with additives. Chapter 8 discusses this in more detail.

Labels on many household products (such as paints, adhesives, and powerful cleansers) warn, “Use in a Well-Ventilated Area.” The same ingredients that enable the high performance of these products may also pollute the air and harm the user through volatile and corrosive chemical gases. Analogous warnings cover accidental ingestion or contact with the skin and eyes.

The SCOR model of supply chains focuses on activities within a company's direct control, such as the sourcing, making, and delivering of a wind turbine, car, or shampoo. As such, this model lacks an important component that is crucial to assessing and managing sustainability: the use phase. Although these seem “out of scope” for SCOR, they do have an environmental impact, and the company that makes these products can affect that impact through the design and servicing of its products, as well as through messaging and marketing activities.55

Maintenance is one reason why Siemens’ role—and its environmental impacts—does not end with the final installation of the wind turbine. Siemens may issue a 5-year warranty for the turbine or agree to a 10- or 15-year service contract. To fulfill the warranties and service contracts, many parts must be readily available to repair a malfunctioning or damaged turbine. In 2013, Dr. Arnd Hirschberg, Siemens’ supply chain manager for wind turbines, estimated that about 9,000 of Siemens’ 2.3-megawatt turbines were in service around the globe, and parts were stocked to service each of them.56 The company keeps as many as 25,000 different parts to service various wind turbine models, stocking as many as 1,500 units per part. Manufacturing, storing, and moving these parts is also part of the challenge of supply chain management and of calculating the wind turbine's carbon footprint: Full environmental assessment requires the mapping of hundreds of additional steps across the supply chain after the product has been delivered.

Interestingly, some companies have changed their business models from selling products to “servicizing” their offerings.57 Instead of selling a product to the customer, the company provides the product's function as a service. For example, Michelin offers trucking companies a “pay by the mile” service for tires.58 In other words, a trucking company may buy 100,000 miles worth of tire usage for a truck. Michelin goes beyond just delivering the tires: It also installs, maintains, replaces, and recycles the tires, guaranteeing that the tires will always be in good working order. Such an arrangement provides more business to Michelin and, at the same time, reduces the transportation company's business risk by turning fixed costs into variable costs. This business model also reduces the environmental footprint of trucking because good, correctly inflated tires—kept in optimal conditions by the tire manufacturer—have a longer life and less rolling resistance, leading to lower fuel consumption and fewer tire replacements.

Such arrangements improve the alignment between manufacturers and customers because manufacturers have strong incentives to build reliable products (leading to the environmental benefits of fewer product replacements), as well as incur less maintenance. Companies that have turned to such a business model include Xerox, through its managed print services,59 Rolls Royce aircraft engines through its TotalCare solution,60 and many others.61

In the SCOR model, the return process is the final operational step for the company and includes procedures for identifying malfunctioning products, deciding on the disposition of packaging, authorizing and scheduling product returns, scheduling return receipts, receiving the returns, disposing of the returns, and verifying and paying all parties involved. These processes require “reverse logistics”—the movement of goods in the opposite direction of the usual supplier–manufacturer–retailer–consumer chain.

The legal and environmental principle of extended producer responsibility (EPR)62 potentially expands the volume of companies’ returns processes. Under this principle, the manufacturer of a product has the social, and sometimes legal, duty to handle the disposal of all the products it makes, in perpetuity. EPR directives in the EU, for example, cover packaging, batteries, vehicles, and electrical and electronic equipment.

The returns process includes more than just the movement of goods from the consumer back to the company or to the company's hired vendor for managing end-of-life products. It also leads to new Source, Make, and Deliver activities if the company refurbishes and resells the used yet usable product, or deconstructs the product to extract valuable (or hazardous) materials, which are then recycled, detoxified, or disposed of in some sustainable way. Chapter 7 delves into these reverse supply chain management activities.

The four operational supply chain processes in the SCOR model are Source, Make, Deliver, and Return. The Plan and Enable processes, by themselves, have a negligible direct environmental impact, but these processes can be the most important levers in terms of the sustainability of many supply chains. Planning and enabling manage the performance of operational processes that consume resources and impact the environment.

These planning processes include decisions on how a product should be sourced, made, delivered, and returned. This means choosing the design, materials, and features of a manufactured good; identifying suppliers and service providers; and communicating expectations. The enable process includes the establishment of business rules, performance indicators, inventory policies, regulatory compliance processes, and risk assessment, to align with the business's strategic plans. It determines the general structure of the supply chain in terms of geography, markets, transportation, and distribution strategies.

In addition to the processes, the SCOR model recognizes five high-level performance attributes: cost, asset utilization, responsiveness, reliability, and agility.63 The first two are internal-facing, whereas the last three are customer-facing metrics.

Discount retailers, such as Walmart, emphasize everyday low prices through cost efficiency. To achieve it, the company minimizes its variable costs and ensures that its sourcing, delivery, store operations, and all other supply chain-related activities are performed efficiently. Other companies emphasize asset utilization. For example, discount airlines also emphasize low cost but do so by maximizing utilization of their expensive assets—their aircraft. They use low prices to ensure high passenger loads, and they emphasize quick turnaround to maximize the aircraft's revenue-earning time (minimizing time spent on the tarmac). Many manufacturers use lean or just-in-time principles, modeled on the Toyota Production System, by working to minimize their inventories, thereby reducing the capital tied up in that inventory.

The last three metrics are customer-facing and measure various dimensions of service. First, responsiveness measures the time-dimension of service—how quickly the company can produce and deliver a customer's order. Amazon, for example, is pushing the boundaries of consumer responsiveness with one-hour delivery services in some cities by positioning inventory near population centers and working with urban delivery and courier services (in addition to using its own vehicles).64 Similarly, fast food outlets often prepare food items before receiving an order, in anticipation of customers’ requests so they can quickly serve made-to-order meals when customers arrive.

Second, reliability measures the certainty of products and delivery. Makers of lifesaving medical products have intensive quality control processes, often hold large amounts of inventory, and ensure on-time deliveries so that no patient ever goes without essential care or receives an incorrect or defective item.

Third, flexibility measures a company's ability to handle large changes in the volume or variety of products. It follows Leon C. Megginson's quote paraphrasing Charles Darwin: “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent. It is the one that is most adaptable to change.”65 Such companies often avoid owning inventory or assets that could become obsolete or could constrain the company's ability to serve volatile demand. Instead, these companies cultivate a varied portfolio of outsourcing partners who can produce as little or as much as the company needs.

Managing sustainability requires additional supply chain metrics to account for environmental impacts within and beyond the enterprise itself, namely the impacts of supply chain operations, including the use and disposal of the product. To this end, many companies measure, manage, and report improvements in various types of environmental impacts as part of, or in addition to, measuring and reporting financial metrics.

In support of these efforts, the 11th version of the SCOR model66 includes “GreenSCOR” under its “Special Applications” section. GreenSCOR comprises a set of environmental metrics that can be measured at subprocess levels and aggregated into the model's plan-source-make-deliver-return-enable framework. GreenSCOR accounts for the carbon footprint, emissions, and recycling associated with each of its level 1 processes by using metrics for:67

GreenSCOR's metrics, however, only measure one side of environmental impact; they only account for the environmentally impactful outputs of supply chain processes. The version of GreenSCOR in the 11th version of SCOR ignores impacts from the consumption of scarce and nonrenewable resources. Thus, a more complete set of SCOR-related impact metrics must encompass both emissions and consumption. Metrics for a supply chain's consumption footprint could include:

Naturally, both emissions and consumption impacts can be weighted by their relative environmental burden and managed against specific regulatory or social-license-to-operate tolerances. GreenSCOR suggests that companies might track COx, NOx, SOx, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and particulate emissions, which are the major types of emissions that the US EPA tracks and regulates. The impact of consumption metrics, such as water and land use, may be judged relative to local levels of water stress or the environmental sensitivity of the local habitat, respectively.

These emission and consumption metrics can be expressed as total quantities across the supply chain or modified to measure progress on specific sustainability goals. Many companies normalize their total environmental impact over the total volume of production, so progress can be demonstrated even as the business grows. For example, AB InBev, the world's largest beer brewer, measures its water footprint in terms of the number of liters of water required to brew a liter of beer and works to improve water efficiency of all its brewing and bottling operations. Coca-Cola uses a similar metric. The British retailer Marks & Spencer chose to measure its transportation carbon footprint in terms of carbon per store. This metric aggregates the many contributing factors that affect its carbon footprint, such as changes in driver behavior, minimization of freight movements, replacement of inefficient vehicles, and the use of low-impact fuels.69

Companies under attack, or fearing attack for perceived environmental transgressions such as using unsustainable palm oil, create metrics and goals that measure the amount of sustainable palm oil they are buying, with the goal of becoming 100 percent compliant by some date. Aggressive goals, such as Unilever's objective to double sales while reducing impact, also call for measuring achievements in stark terms. For example, Unilever measures its progress on solid waste emissions not in terms of total tonnage sent to landfills or waste per unit of product, but in terms of the percentage of its factories that have achieved the “zero waste-to landfill” goal. This creates competition among its factories and a “race to the top” among factory managers.

Consumption and emission patterns take place at each stage of every supply chain. By uncovering what is happening to the environment in their names, companies can begin to decide whether and how to address these impacts.