Figure 11.1 The Dong-In Mico site on Patagonia's Footprint Chronicles

On June 11, 2012, a bearded and ponytailed David Bronner locked himself and several cannabis plants inside a 64-square-foot steel cage in Washington, DC's Lafayette Square, directly north of the White House. He was trying to make enough hemp oil to spread on a piece of French bread. First, the police tried to cut the cage bars with bolt cutters, but failed. Next, the authorities attempted to haul the cage away with a tow truck, but that too failed.1 It took police three hours to cut through the bars with a chainsaw, get to Bronner, and arrest him on charges of “blocking passage” and possession of marijuana.2

Anecdotes such as this may make David Bronner seem like just another protester for marijuana legalization, but he's actually the CEO (which in his case stands for “Cosmic Engagement Officer”) of Dr. Bronner's Magic Soaps and is deeply concerned with environmental sustainability. Although most companies seek to maximize financial performance within the constraints of regulatory or social requirements, deeply sustainable companies, such as Dr. Bronner's, Seventh Generation, and Patagonia, flip these goals and constraints. That is, they seek to minimize environmental impact, subject to financial viability constraints. These “deep green” companies use their social and environmental strategy as branding and identity mechanisms—they sell to “green” customers and attract “green” job applicants.

Whereas most CEOs assiduously avoid controversies, especially ones involving criminal prosecution by the humorless US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), this wasn't Bronner's first run-in with the authorities. In 2001, he joined activists in front of DEA buildings nationwide to offer drug enforcement officers a taste-test comparison between hemp foods and poppy seed bagels.3 In 2009, he was part of a group arrested while planting hemp outside of DEA headquarters.4 In all three cases, he was protesting US policy prohibiting the growing of hemp, a strain of Cannabis closely related to marijuana but which lacks consequential amounts of marijuana's psychoactive chemicals.

During the Washington cage stunt, Bronner spokesman Ryan Fletcher said, “He's doing this action in part because he wants to be able to source that hemp oil from American farmers, rather than exporting his dollars to Canada.”5 Bronner wanted local sourcing, which is one of the tenets of the company's culture of environmental sustainability.

Most corporations would be horrified by such radical behavior by the CEO, but the leaders of privately held Dr. Bronner's have always freely mixed activism with business practices, ever since the company's 1948 founding as a nonprofit religious organization.6 Founder Emanuel (“Emil”) Bronner (known as Dr. Bronner, despite lacking a formal doctoral degree), developed an “All-One!” vision to unify humanity on “Spaceship Earth.” His voluminous writings on the morality of uniting all mankind (and the godliness of cleanliness) form a patchwork of fine print on the labels of the company's products.7 After the founder passed away, and under IRS pressure, the company dropped its claim to be a religious organization. In the early 1990s, Bronner's son Jim took over, and in 1998 (after Jim's death), his son David Bronner assumed the role of CEO.

A dedicated activist, David Bronner continued his grandfather's legacy of change, by making Dr. Bronner's products as natural as possible while having the lowest possible environmental impact. Advocating for hemp cultivation has been part of this approach, citing the fast-growing plant as a renewable resource that provides high-quality fiber, edible oils, high-quality protein, and animal fodder.8 In 1999, David Bronner replaced his soap's existing caramel coloring with hemp seed oil, which also creates a smoother lather.9 That choice put him in conflict with US authorities, because DEA policies conflate hemp with marijuana, despite hemp's lack of intoxicating effects.10 The law forced the Californian company to import hemp oil long distances from Canada, where the source crop can be legally grown.11

Given its sustainability philosophy, Dr. Bronner's does not make the same trade-offs that most public companies do when evaluating a project. “All of our deep ideas about sustainability and sourcing—all that extra expense, our charity as a company—is at the heart of our cost of goods sold,” said Michael Milam, Dr. Bronner's COO.12 “Once you build your supply chain like that, it doesn't become an option for swapping it out if things get tight.” That commitment has been an integral part of the company for more than six decades, even during its brush with bankruptcy in 1985.

Hemp isn't the only environmental issue, or even the largest one, that Dr. Bronner's has tackled. In 2006, the soap maker started to align its supply chain with its beliefs by sourcing only certified Fair Trade ingredients through the Fair for Life program.13 The company immediately ran into a challenge with coconut and palm oils, two of Dr. Bronner's largest ingredients by volume. The company's oil brokers could not verify the labor and environmental practices behind every batch of oil purchased. It was the same traceability issue that bedeviled many large companies, such as Nestlé and Unilever, which source from the global commodity market of palm oil (see chapter 5).

Bronner's response was to bypass the brokers and invest in vertical integration. The company built its own mill in Ghana and acquired a coconut oil processing facility in Sri Lanka. “There wasn't Fair Trade coconut oil, and so that's why we have a mill in Sri Lanka, specifically to have that,” Milam said. Once the company owned the mill, it sourced coconuts only from local smallholder farmers, of whose practices the company approved.

Although vertical integration and direct control of the sources of raw materials reduced Dr. Bronner's environmental exposure in its supply chain, it increased both its business risks and its costs. Commodities are traded on world markets in order to pool risk and resources (including processing, transportation, and sales) of hundreds or thousands of small suppliers, thereby increasing efficiency and reducing the volatility of supplies and prices. In contrast, by having its own coconut oil and palm oil growers and mills, Dr. Bronner's Magic Soaps de-pooled that supply risk, exposing the company to shortages if its growers in Sri Lanka or Ghana had a bad year. In addition, Dr. Bronner's had to pay the start-up costs to get these small mills up to its standards. In the first years, the company even had to prepay for crops before they were planted. “We have to pre-finance the crops,” Milam said in a 2013 interview.14 “This forces us to be very good at projections.” To minimize shortages or excess capacity, Milam explained that the company maps ingredient usage on a four-year horizon. “We can't just pick up the phone and get materials and expect that someone's going to get it for us.”

In 2008, Dr. Bronner's Magic Soaps sued a group of competitors, chiefly the $11 billion cosmetics giant, Estée Lauder. The suit alleged that these companies were labeling products as organic even though they contained petrochemical ingredients.15 Also named in the suit were Stella McCartney's CARE, JĀSÖN, Avalon Organics, Nature's Gate, Kiss My Face, and Ikove, among others. Dr. Bronner's specifically targeted ECOCERT, a European accreditation organization, that certified products as organic even if their organic content amounted to no more than 10 percent of the product.16 Nevertheless, the companies were not breaking any laws because the USDA certification requirements for organic body products were not clearly defined.

Dr. Bronner's, whose products boast entirely organic ingredients, felt that the competitor's use of the organic label on products containing any amount of nonorganic ingredients was misleading consumers and diluting Dr. Bronner's own brand. The company did not want the organic label to become an “Akerlof lemon” (see chapter 9). Following the filing of the lawsuit, some companies quickly settled. For example, Juice Beauty Inc. agreed to change its product formulations. Whole Foods Market sided with Dr. Bronner's, telling the offending companies to fix the problem within 12 months or be removed from the retailer's shelves.17 The lawsuit was dismissed four years later when a California federal court declared that the interpretation of USDA standards for organic certification was outside its jurisdiction. Dr. Bronner's, however, had already made its point both to its competitors and to its consumers at large.18

Emil Bronner, the eponymous founder of Dr. Bronner's, believed in “constructive capitalism,” in which you should “share the profit with the workers and the earth from which you made it.”19 That belief underpins the company's emphasis on fair trade sourcing. It also led David Bronner to voluntarily cap the compensation of his company's executives—including himself—at $200,000 per year, or five times the salary of the company's lowest-paid full-time worker.

Dr. Bronner's uncommon business practices and radical leadership did not hurt its growth: The company grew from $6 million in sales in 2000 to $80 million in 2015, riding the expanding environmental movement. Along the way, the company said “no” to a lot of opportunities. In fact, during its rapid growth from the late 2000s to 2014, the company received so many buyout inquiries that CEO David Bronner threw them directly in the trash without looking at them.20 “What we're doing is pretty radical; this is not feel-good sustainability, buying offsets and crap like that. This is taking on the Drug Enforcement Administration. My intention is never to sell,” he said.21

Most companies dream of landing lucrative distribution deals with big retailers, but when Walmart approached Dr. Bronner's about a transaction, Dr. Bronner's said “no” to the world's largest retailer. According to David Bronner, he and other company leaders didn't like what “Walmart stands for.”22 Having Walmart as a customer may have significantly increased the company's revenue and reach but may also have created tensions with Dr. Bronner's core consumers and natural foods retailers.

Given Patagonia's emphasis on high-quality outdoor apparel, it is not surprising that the company aims to attract nature lovers as customers. Although chapter 1 cites evidence that the average consumer is not willing to pay a premium for more sustainable products, Patagonia's customers aren't average consumers. An analysis of the effects of the company's switch to higher-cost organic cotton in 1996 showed that Patagonia's customers continued to buy, paying a premium that exceeded the additional cost of that cotton.23

Patagonia's founder, Yvon Chouinard, has long prioritized sustainability over short-term financial gains in the company's business model. “Growth isn't central at all, because I'm trying to run this company as if it's going to be here a hundred years from now,” he said.24 “We measure our success on the number of threats averted: old-growth forests that were not clear-cut, mines that were never dug in pristine areas, toxic pesticides that were not sprayed,” Chouinard wrote in his book Let My People Go Surfing.25 Like Dr. Bronner's, Patagonia pushes other companies to “do the right thing.” In 2002, Chouinard cofounded the group “1% for the Planet,”26 which was modeled after a program he had started at Patagonia in 1985.27 The group contributes 1 percent of total revenues to environmental causes. In 2017, the group's website listed 1,319 member companies.

“We operate on the credo that being in business and doing the right thing are not mutually exclusive,” said Dave Abeloe, distribution center director for Patagonia. “For everything we do, we look at the impacts on the environment and try to figure out how we can lessen those impacts.”28

Even so, lowering the total impact occasionally means using less sustainable materials. “We don't want to sacrifice quality for [short-term] environmental reasons,” said Jill Dumain, Patagonia's director of environmental strategy. “If a garment is thrown away sooner due to a lack of durability, we haven't solved any environmental problems.”29

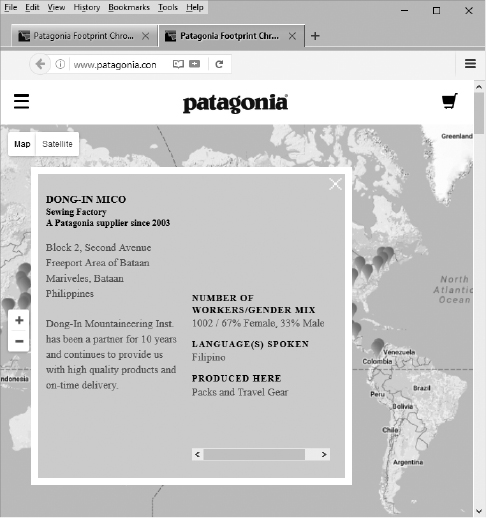

To bypass the confusion, mistrust, and “fog” associated with environmental claims and sustainability labels, Patagonia chose a bold approach. It took transparency beyond the ingredient level of “what's in this product's formula” to also reveal “who made this product.” Frustrated by the state of eco-labels and corporate social responsibility reports, Patagonia launched the Footprint Chronicles on its website in 2007.

The Chronicles provide customers (and anybody else who cares to know) with detailed information about the supply chain for each of many of the company's products. Each product's page includes not only detailed features, materials, qualities, and customer reviews, but at the bottom of the page, Patagonia also shows the main suppliers involved in making the product, along with information about each of them. For example, according to the Chronicles, the Patagonia Windsweep 3-in-1 jacket is sewn by Maxport Ltd. in Vietnam, using fabric woven, dyed, and finished by Nantong Teijin Co. in China, with textiles supplied by TWE-Libeltex BCBA in Belgium and Everest Textile Co. Ltd. in Taiwan.30

In addition, the link to the Footprint Chronicles brings up a world map dotted with pins representing each of Patagonia's major supplier and manufacturing locations.31 Clicking on a pin shows the activities at that location and information about what is made there, the composition of the workforce, and their history with Patagonia (see figure 11.1).

Figure 11.1 The Dong-In Mico site on Patagonia's Footprint Chronicles

Patagonia has effectively made its supply chain transparent to anyone who wishes to verify the environmental or social claims the company makes about its products. Public response to the Footprint Chronicles has been overwhelmingly positive. Media outlets, ranging from business magazines to rock climbing community publications, have reported on the project, earning Patagonia positive exposure in its core market. Other progressive companies, including Seventh Generation, said they wished they could create something as transparent as the Footprint Chronicles.32 Some companies followed suit, with applications such as Stonyfield's supply chain map,33 using an MIT-developed tool SourceMap, a “social network” style representation of supply chains.34

As chapter 3 shows, even just collecting the data and keeping it current can be a challenge. Many deep-green companies try to show their customers the complete story behind the product they offer, intensifying the challenge of transparency.

Radical transparency can become especially tough when the story is not very rosy. In 2009, Patagonia hired Indian firm Arvind Ltd. to supply denim. The textile supplier had a reputation for environmental sustainability and fair worker treatment. As part of its supply agreement, Patagonia required Arvind to allow third-party factory audits. Patagonia also sent its new director of environmental and social responsibility, Cara Chacon, to investigate for herself, and she found some problems.

Following Chacon's visit, Patagonia published a photo slideshow titled, “Growing Pains,” and added it to the Chronicles. The photos detailed not only the positive reasons why Patagonia chose Arvind, but also the supplier's shortcomings. On the plus side, Arvind had installed a system to cleanse wastewater so thoroughly that it could be safely discharged into the local sewer system.35 On the minus side, Arvind had an unprotected concrete-edged wastewater drainage ditch, which created a safety hazard. Following Chacon's visit, Arvind installed a railing around the ditch's edge to prevent workers from falling in. Later, Patagonia posted a corresponding photo to prove it.36

Being open about environmental challenges, as well as successes, is a line the company wants to cross, according to Patagonia's Dumain. “If we started to squirm in our chairs a little bit, we were probably hitting the right point,” she said when explaining the Chronicles. Patagonia strives to surpass the level of public disclosure exercised by most companies or any labeling program. That requires transparency from suppliers as well as communicating complex information to consumers. It means not only revealing the situation “as is”—a difficult task in its own right—but also showing the history of mistakes, corrective actions undertaken, and their consequences. Identifying specific worker safety or environmental issues at a supplier factory, and then demonstrating that they were remedied, does not neatly fit on a sticker or a hangtag.

One issue Patagonia has had to address was the use of perfluorocarbon (PFC) fabric treatments, the manufacturing and use of which releases perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) as a by-product. Certain PFCs are prized for their ability to resist water, dirt, and oil. They have been widely used for many decades on products ranging from furniture, clothing, tents, car seats, and electronics, to grease-resistant food packaging such as microwave popcorn bags, fast-food wrappers, and pizza boxes.37 Unfortunately, this resistance is a double-edged sword; these chemicals are also vilified for their ability to resist breakdown when released into the environment (from factories, during use, when washed, and in the waste stream). PFOA and other PFCs can accumulate in plants, animals, human blood, and even breast milk. A wide variety of studies suggests that some of these chemicals are hazardous, especially at high levels, and governments are steadily moving toward restricting their use.38

As more global attention was focused on the use of PFOA and other PFCs as water repellents in outdoor textile products, Patagonia chose to be transparent on the issue during the fall 2007 launch of the Footprint Chronicles.39 The revelation did garner some angry comments, but it also won significant praise for the company's aggressive honesty. “Transparency defuses conflict,” said Dumain. “Issues like PFOA, which might have led to confrontations, have instead prompted fruitful conversation.”40

In the winter of 2012, Greenpeace published a report criticizing Patagonia and 12 other outdoor apparel makers over the presence of PFOA and various PFCs in the makers’ clothing.41,42 The attack surprised Patagonia, who felt it had been very open about the issue and was working to eliminate PFOA. In the aftermath of the attack, Greenpeace further criticized Patagonia's response for not promising a deadline for the removal of all PFCs.43 For its part, Patagonia wrote, “We don't feel comfortable promising a path forward that hasn't yet been identified—that simply isn't fair given the complexity of this challenge.”44 Greenpeace's reply to this response was that “this is difficult to accept considering that PFC-free alternatives are already available on the market.”45

Often businesses are accused of having a narrow, short-term mindset regarding environmental issues. Perhaps surprisingly, it may be Greenpeace who is taking the narrower, short-term view in fixating on just the impact of PFCs. Greenpeace claims that the alternative water repellant treatments are good enough, because “the decisive factor is optimal water repellency.”46 But Patagonia takes a broader view that none of the PFC-free alternatives have the durability of PFCs in resisting water, soil, and grease over time, which means current PFC-free jackets must be replaced more frequently.47 The environmental impact of replacing a 360-gram jacket48 that becomes quickly soiled or worn out exceeds the impact of about 0.0002 grams of PFCs found in that jacket.49 Some within Patagonia wondered if there were people in Greenpeace who were sensationalizing an issue of little merit. Ironically, even while the dispute was taking place, Greenpeace was using Patagonia's products in the Arctic. (Greenpeace personnel were fighting oil drilling there.)

Patagonia, for its part, has tested dozens of possible PFC alternatives. It has switched its water-repellent fabric treatment to shorter-chain PFCs, which are not as contentious because their by-products are less bio-accumulative and less persistent in the environment than PFOA.50 The company has said, “Patagonia's temporary solution, which is also being adopted by a number of manufacturers, is not good enough, but it's the best option we have found so far.”51 Patagonia continues to work with bluesign technologies, a Swiss company, and other apparel industry companies, as well as chemical suppliers and mills, to find alternatives. Patagonia has also made a strategic investment in another Swiss company, Beyond Surface Technologies AG, which is working to develop compounds with lower environmental impacts for outdoor apparel.52

Finally, there's no guarantee that PFC-free will actually be greener than PFCs. All of this has led Patagonia to some soul searching. Rick Ridgeway, vice president of external engagement said, “We started to wonder if we should even been [sic] making a product because it's that bad. … This is a tension that goes on every day in our company. There isn't an apparel company in the world that considers environmental issues that doesn't face this issue. We like to dialogue with customers because some of these issues are so thorny that you can't address them without help.”53 Patagonia feels it does have a responsibility to produce the best possible products within all the trade-offs inherent in apparel manufacturing and then to be transparent about those choices and what is known about their impacts.

Patagonia's Footprint Chronicles revealed an especially challenging problem—it demonstrated consumers’ limited comprehension of detailed sustainability-related information. When the site debuted, it included data on each product's carbon footprints, water use, and waste. However, the company found that many consumers didn't understand the implications or were overwhelmed by the level of detail. That data have since been removed.

“I think it was fairly new for people, and I think it was hard for people to question what we were saying,” said Eliss Foster, senior manager of product responsibility at Patagonia. In that regard, Patagonia faced the same issue of data comprehension and comparability that bedeviled Tesco's “black foot” carbon label program (see chapter 9). Patagonia's competitors lacked the same level of disclosure, so Patagonia's customers could not compare and contrast impact numbers. The company intends to restore the environmental impact data when the apparel industry develops a standardized environmental impact measuring and reporting system. To support that outcome, Patagonia helped found the Sustainable Apparel Coalition, which is developing such a system54 (see chapter 12).

The Footprint Chronicles also reveal Patagonia's inner workings to rivals and critics. In theory, competitors could “reverse engineer” Patagonia's products for commercial gain, because the Chronicles list each supplier's street address and details about materials, products, or parts made there. In addition, such full disclosure enables NGOs, government agencies, and journalists to easily investigate the supplier and connect it to Patagonia. Naturally, the latter is Patagonia's key rationale for the disclosure, and the company considers any resulting criticism to be an opportunity for improvement.

This transparency also extends upstream and flattens traditional walls around suppliers’ proprietary information. Patagonia's Dumain said that some of Patagonia's suppliers initially balked at allowing public insight into their operations, “We have very blunt language of the good and the bad and what we think,” she added by way of explaining the suppliers’ reluctance. Nevertheless, Patagonia may have experienced less supplier resistance than other companies could have encountered, because the company has a good reputation and generous supplier remuneration practices. Even though Patagonia's volumes are relatively small with many of its suppliers, it pays more than many other apparel companies do for comparable products.

As the reputation of the Footprint Chronicles grew, many of Patagonia's suppliers began to see their inclusion in the Footprint Chronicles as a badge of honor. In 2013, only one of the company's suppliers had not been profiled. According to its mini-profile, the owners of Vietnamese sewing factory Maxport JSC asked for their details not to be included. Patagonia honored that request but added, “We consider Maxport's employment practices, as well as the quality of its work, to be among the best of all our suppliers.”55

Although the Footprint Chronicles seem like a paragon of supply chain transparency, they are primarily limited to covering Tier 1 suppliers. Getting information about Tier 2 (and deeper-tier) suppliers is more difficult. To monitor Tier 2 suppliers in China and elsewhere, Patagonia works with bluesign technologies and several NGOs.56

The Footprint Chronicles may have been intended as a consumer communications channel, but it also lets suppliers see each other's practices. “Because our suppliers like it, they watch it. They learn from it,” said Randy Harward, Patagonia's quality director.57 Harward believes that suppliers viewing other suppliers’ practices and copying them has accomplished more within Patagonia's supply chain than almost anything else that Patagonia has done.58 “It is beyond our wildest dreams successful,” Harward said.59

In that regard, it is akin to the supplier and supply chain development efforts of Seventh Generation and of Natura (see chapter 12), in which these deep-green companies nurture the development of sustainable practices among their suppliers and throughout their industries. Dumain noted that a group of firms with progressive sustainability agendas—Stonyfield Farm, Aveda, Ben & Jerry's, and Seventh Generation—have long informally shared best practices. “These companies have been working together for years to raise the bar,” said Andrea Asch, manager of natural resources at Ben & Jerry's. “That's where Patagonia is with these Footprint Chronicles—that's the new bar.”60

Patagonia gives its sustainability and social responsibility associates “veto power” over the company's choice of suppliers. This veto power applies to Tier 1 and Tier 2 factories. Suppliers notify Patagonia about their intention to use a new candidate factory to fulfill a production batch. Patagonia then audits the supplier using a scorecard covering: (i) business aspects such as price, capacity, and delivery capabilities; (ii) quality; (iii) social responsibility; and (iv) environmental responsibility.

According to Patagonia's Chacon, in 2013 the company vetted the factories of 18 potential suppliers. Five of them were “approved” and 11 more received a “conditionally approved” status owing to low-, medium-, or high-risk issues (which could include either environmental or social issues), but no “zero tolerance” issues (such as child labor, forced labor, abuse, or harassment). Patagonia negotiated remediation of the identified issues with these conditional suppliers, usually before orders were placed. Two factories were vetoed for zero tolerance issues: child labor (in China, age 15) and refusal to admit Patagonia's third-party auditor into a factory (in Vietnam).

As mentioned above, Patagonia has been working with bluesign technologies, which categorizes textile industry chemicals as blue, safe to use; gray, special handling required; and black, forbidden under its standard.61 Patagonia's requirement that more and more suppliers adhere to bluesign's specifications may result in “some changes to our supply chain,” according to Steve Richardson, Patagonia's director of material development.62

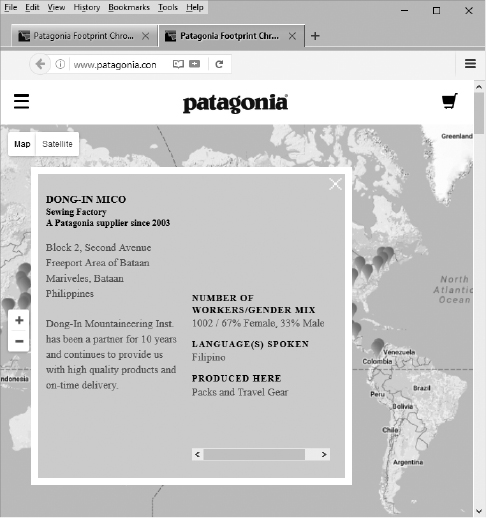

“DON’T BUY THIS JACKET”63 is not the typical marketing slogan that most sales-hungry apparel companies would emblazon in a full-page New York Times ad (see figure 11.2) on Black Friday—the day after Thanksgiving in the United States and the country's biggest shopping day of the year. The ad encouraged consumers to buy second-hand Patagonia apparel instead. These used clothes were offered by independent eBay sellers under an arrangement between eBay and Patagonia.

Figure 11.2 The New York Times ad

This arrangement had its roots in 2011, when eBay started approaching major brands, like Patagonia, to develop portals through which reliable sellers could sell used products.64 Patagonia signed on as part of the clothing company's larger “Common Threads” initiative, which promotes conscious consumption through resale, reuse, and recycling of Patagonia products. Sellers on eBay who want their auctions listed on Patagonia's website must pledge to “help wrest the full life out of every Patagonia product”65 by buying used when possible and selling their Patagonia clothes when they're no longer in use.66

A November 2013 search on eBay found listings for 24,524 Patagonia items in 14 different product categories.67 Sellers advertised their items with positive language like a “great lightweight jacket for layering”68 or “maximum warmth with minimal weight.” At the European launch of the joint program with eBay, Patagonia's Vice President Vincent Stanley joked that the eBay partnership may be a kind of customer loyalty program, but “it may be the only one in the world that is based not on more sales but perhaps on fewer.”69

Most brand owners perceive sales of their used or refurbished goods as cannibalizing new sales. Caitlin Bristol, senior manager of global impact for eBay, commented: “We often get, as you might imagine, handfuls of cease-and-desists demands and angry calls, particularly from high-end luxury brands, about their products showing up second hand on eBay.” For Patagonia, however, the calculus was different. These second-hand sales help Patagonia achieve its long-term environmental objectives. “The greenest product is often one that already exists,” said Lori Duvall, global director of green at eBay. From 2005 to 2013, Patagonia recycled more than 56 tons of old clothing returned to its retail locations.70 In 2013, the company began selling used Patagonia products directly at four of its stores.71

Interestingly, the initiative actually helped sales of new apparel in three ways. First and foremost, it was a testament to Patagonia apparel's durability. Second, for consumers worried about spending $400 on a new jacket, knowing that Patagonia provides a venue to resell the jacket in the future can help ease the purchasing decision, Duvall said.72 Last, selling used clothing brings less affluent consumers into the brand's fold by enabling them to purchase less pricey second-hand products, creating long-lasting brand engagement. Thus, paradoxically, not only did Patagonia's “Don't Buy This Jacket” campaign not stunt its growth, the company grew by 27 percent by 2013, reaching $575 million in sales. In fact, the eBay initiative was so successful that an advertising industry publication questioned whether it was just a marketing ploy.73

Seventh Generation's name comes from the Iroquois constitution (the “Great Law of Peace”). This Native American confederacy urged leaders to consider the impact of their actions on their descendants seven generations into the future.74 The maker of household and personal care products was founded in Burlington, Vermont, and has taken a progressive approach to business since its earliest days in 1988.75 Taking the long view on its products, Seventh Generation's leaders and employees have worked to push and pull the rest of the industry to act in an environmentally responsible mold.

“The old business model focused exclusively on profit is no longer viable, and the world needs to forge new economic and social systems built on sustainability,” said John Replogle, CEO of Seventh Generation. He made this comment after the United Nations named his company a “Leader of Change” in 2011.76 Jim Barch, director of research and development for Seventh Generation said, “I would argue that one has to examine the meaning of ROI in a broader context than is normal, because most companies are trying to show they've created wealth, when we're trying to show we are actually creating value.”77

Many mainstream companies employ a phalanx of lawyers, marketers, and public relations experts whose sole duty is to prevent embarrassing stories or sensitive tidbits from escaping the fortress constructed around their proprietary information. “What people don't know, they can't protest” may well be the motto of these professional enforcers of corporate reticence. In contrast, Seventh Generation has long engaged in “radical transparency,” which entails openness about the company's products and activities.

Whereas many companies have “secret formulas” or only disclose generic ingredient terms (e.g., “fragrance” or “preservative”), Seventh Generation publishes complete lists of all ingredients in each of its products. For example, the company's baby lotion lists 20 different specific ingredients.78 Seventh Generation is confident about these disclosures because of its careful ingredient selection processes. “We adhere to the precautionary principle, meaning that substances are guilty until proven innocent in our eyes,” said Heidi Raatikainen, associate scientist.79 That is, the company is not satisfied with just an absence of evidence of toxicity—it looks for evidence of absence of toxicity. Jeffrey Hollender, the company's cofounder and former CEO, wrote, “Publicly sharing all our activities preempts the critics, and more eyes on the company's activities means more advocates and friends.”80

This policy can cause problems with suppliers, however. Clement Choy, senior director of research and development for Seventh Generation, noted that some fragrance companies in particular are very nervous about disclosing confidential business information, such as their ingredients, for competitive reasons. However, he added, “part of our principle of working with a fragrance company is you need to tell us 100 percent what's inside, because we're going to put it on our bottle. And there were some fragrance companies that walked away from the table and said as a principle value, our values aren't aligned.”81

Only a small percentage of Seventh Generation's customers actually want to know every ingredient in every cleaning product they bring into their home, according to Reed Doyle, the company's former director of corporate social responsibility. “We did it because we knew if we did it … everyone else would be forced to follow,” he said, “and that's exactly what happened in the cleaning products industry. … This group called Women's Voices for the Earth went out there and pointed fingers at a lot of these guys [other cleaning product companies] and said, ‘Hey, consumers have a right to know what's inside.’”82

Like Patagonia, Seventh Generation believes that self-criticism can be healthy. Hollender once penned a critique of his company's own products and posted it on the company's website.83 His competitors, he said, told Seventh Generation's retail customers of the self-critique.

Whereas competitors expected the self-critique to damage Seventh Generation's reputation, according to Hollender's account, many retailers responded by asking the competitors for their own self-critique. “The reality is, our [ingredient] list, as bad as it was, was better than the list that all our competitors had,” he said during his presentation at the 2010 World Innovation Forum. “And in most cases, our competitors wouldn't even provide the buyer with a similar list.”84

Similar to Dr. Bronner's, Seventh Generation also acts like an environmental activist at times. The company encourages environmental NGOs to test Seventh Generation's products against similar products from its competitors. Martin Wolf, Seventh Generation's director of product sustainability and authenticity, may even tip off an NGO that certain competing products contain an objectionable chemical, such as a known carcinogen.

In the short-term, these NGO-like actions serve the business interests of companies like Seventh Generation and Dr. Bronner's, earning them goodwill with their deep-green customers and putting competitors at a disadvantage. “As a result, we may come out on top,” Wolf said. “But again, it's about how do we push the industry in the right direction.” In the long-term, this strategy may raise the environmental bar for the entire industry, which is the ultimate objective of these deep-green companies.

In 2004, members of the American Cleaning Institute debated whether to add sustainability to the organization's core mission. Some members wanted to relegate sustainability to committee work that supplemented the existing mission. Seventh Generation's Wolf said, “I argued that no, you can't have a small box to the side called sustainability. It had to be core to the mission of the association. And they rewrote the charter of the American Cleaning Institute to include sustainability.”85

In general, corporations lobby against tighter regulations that might force them to redesign products, increase costs, or limit innovation. However, some deeply sustainable companies actually lobby for regulation, as both a sustainability initiative and a competitive tool that creates a burden for less sustainable companies. To transform its industry, Seventh Generation joined with several NGOs on campaigns across the country to pressure state legislatures to regulate chemicals.86 It teamed with notable environmental activist Erin Brockovich87 and other companies like Stonyfield Farm as part of the Companies for Safer Chemicals Coalition.88 Seventh Generation even sent its own scientists to legislative hearings to wage a protracted campaign to ban the use of phosphates in dishwashing detergents (see chapter 8).89,90

In November 2009, a video was posted online featuring a babbling baby calling on other babies to crawl to Washington, DC. “Just put one hand in front of the other, followed by one knee in front of the other, and then sort of use your foot to scoot along,” said the subtitled translation of the baby's babbling. “To Washington! In order to demand a law that will eliminate toxic chemicals found in household products,” urged the infant activist.91

The video was part of a campaign called the “Million Baby Crawl” (a play on the 1995 “Million Man March”92). Adorable and infectious, it was nearly the polar opposite of the gruesome and poignant Greenpeace video attacking Nestlé's use of noncertified palm oil in KitKat bars (see chapter 1). The Million Baby Crawl video also featured a company product: the animated baby delivered its campaign speech from atop a literal soap box—one with a Seventh Generation label on it.

Beginning in 2009, Seventh Generation focused much of its activism on reforming the 1976 Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA). The original act prohibited manufacturers from using substances not on the “TSCA inventory” without first providing the EPA with information on the chemical's impact on human health and the environment.93 The original TSCA inventory automatically admitted about 62,000 chemicals already in use in American commerce without any testing at all. Nearly four decades after the old law's passage, the EPA had reviewed the health and safety of only about 200 of those grandfathered-in chemicals.94 Seventh Generation urged legislators to increase the number of chemicals tested and to prevent adding new chemicals to the TSCA inventory without a thorough EPA review. Initially, the Million Baby Crawl campaign achieved very little formal legislative progress.95 In 2016, Congress passed reform legislation that Seventh Generation said was “some improvement over current law, [but] it still falls short of our goals.”96

While Seventh Generation used legislation and competitive pressure to force other household cleaning companies to reduce their environmental impacts, the company also made it easier for competitors to do so. “We're willing to give up rights for the greater good,” said Martin Wolf, of Seventh Generation. For example, a collaboration with Rhodia, one of the company's suppliers, found a biological source for a feedstock ingredient that had previously only been available from petroleum-derived sources. India Glycols, a supplier of plant-based bottles for Coca-Cola, had created a bio-based ethylene gas that Rhodia and Seventh Generation could use to synthesize cleansers. Even though Seventh Generation was the driving force behind the innovative use of the plant-based material developed by Rhodia, Seventh Generation did not demand a period of exclusivity from its supplier. “We said all we want to do is be first, and we'll do a co-announcement. And the co-announcement was probably more important to Rhodia than supplying us the couple million dollars’ worth of plant-based chemicals,”97 said Wolf.

While this open approach to research and development allows competitors to “catch up” quickly, it also offers Seventh Generation a subtle competitive advantage. It encourages suppliers to come to the company with new ideas, because they know that Seventh Generation will not pursue restrictive rights or exclusivity beyond a short period, which allows the supplier to grow revenues through broader sales of the new material. “It's amazing the type of collaborators we get that come to us and say, ‘We want to work with you, because we see the speed to market, we see that you can bring things in a lot faster,’” said Seventh Generation's Choy. “There's a lot of different people that would probably never come to a $150 [million], $200 million company, but because of our way of going about business, I think there's an intrigue there that we can help prove concepts that will eventually lead to commercialization of that particular product of their platform.”98

Seventh Generation is not alone in its innovation-sharing approach. Motivated by the same philosophy, Patagonia shared its development of Yulex bio-rubber extracted from the guayule plant, which entered the market in 2012.99 Patagonia is using this naturally derived rubber to replace petroleum-derived neoprene in wetsuits and is sharing the technology, because the company is committed to increasing the environmental sustainability of the entire industry. Just like Seventh Generation's sharing arrangements, such a move encourages scaling of new material manufacturing, reducing its cost, and fueling further growth for Patagonia.

Dr. Bronner's, Patagonia, and Seventh Generation exemplify what might be called “deep green” companies. These companies often sell premium-priced products backed by a story and the environmental credentials of the product or company. They serve a comparatively small customer segment that shares these environmental values and that is often willing to pay a higher price relative to mainstream offerings of similar performance.

Mainstream public companies face several challenges in replicating this model. Unilever CEO Paul Polman would likely lose his job if he caged himself in front of the White House or 10 Downing Street in the name of any environmental issue. David Bronner can do so because his customers and private owners are as committed as he is and even applaud such acts. Dr. Bronner's serves a narrow, eco-conscious market niche, while Polman must satisfy a wide range of customers, most of whom are more price sensitive than environmentally sensitive. Polman must also satisfy his public shareholders, bondholders, and the financial markets, who are crucial suppliers of the capital that Unilever requires to operate. These stakeholders may be generally less concerned with Unilever's social and environmental mission than they are with high returns on their equity investments and low-risk repayment of debts.

Regardless, Unilever has committed itself to environmental stewardship. In 2015 Polman declared, “In a volatile world of growing social inequality, rising population, development challenges and climate change, the need for businesses to adapt is clear, as are the benefits and opportunities.” He added, “This calls for a transformational approach across the whole value chain if we are to continue to grow.”100 The company created a series of sustainable brands that have accounted for half the company's growth in 2014 and that grew at twice the rate of the rest of the business. Many green bloggers and publications picked up this statistic.101

The Financial Times, however, reported that some displeased shareholders perceived that Polman cared more about the environment than about the business. In an article titled, “Paul Polman's Socially Responsible Unilever Falls Short on Growth,”102 the paper cited revenue reductions in 2013 and 2014. It also noted that while the FTSE Consumer Goods Index grew by 80 percent during Polman's tenure, Unilever share price grew by only 40 percent during the same period.

The trade-off between economic viability and environmental sustainability is at the heart of a long-running debate over the responsibilities of corporations and their decision makers. In a 1970 article titled, “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits,” Milton Friedman, the noted Chicago economist, argued for the supremacy of the title's thesis.103 For public companies, this requires serving their shareholders through ongoing growth of the company's stock price, dividends, and other financial returns. Friedman was reacting to a view that corporations also have social responsibilities to other stakeholders—their employees, the communities they operate in, the environment, and society at large, as articulated, for example, by Edward Freeman in his 1984 book, Strategic Management: A Stakeholders Approach.104

US investor protection laws side with Friedman's view, stating that the fiduciary duty of managers is to maximize shareholders’ value. Although a company's managers have broad discretion under the doctrine of the business judgment rule,105 they must ultimately serve as the stewards of their investors’ financial resources. Note that within that context, eco-efficiency, eco-risk mitigation, and eco-segmentation initiatives are adequately aligned with shareholder interests. Managers may also engage in some level of philanthropic efforts as long as the outlays seem to support profit-driven strategies such as marketing or branding initiatives.106 Despite all that, the companies in this chapter seem to go beyond these aligned activities when they reveal unfavorable facts about the company (radical transparency), aid competitors in becoming more sustainable (open sharing of competitive data and innovation), pay suppliers more than the minimum required, or forego lucrative business opportunities (eschewing large distribution deals or promising new raw materials, on sustainability grounds).

Although a company's failure to maximize shareholder value is not a criminal issue, it does portend a potential civil dispute between shareholders and management. Profit-preferring investors could potentially sue a firm in civil court for excessive investment in sustainability. Thus, the legal risks depend on investors’ views on sustainability. Patagonia, Dr. Bronner's, and Seventh Generation are all privately held, which enables the companies to avoid such risks; their investors agree with the firms’ priorities. In 2002, Patagonia CFO Martha Groszewski said, “It would be very difficult for us to be who we are [if the company were publicly owned]. The programs we support would be seen as unnecessary.”107 Former Patagonia Executive Vice President Perry Klebahn added, “There is not as much pressure for growth as if we were publicly traded.”

One way for investor-backed corporations to engage in substantive amounts of activities other than profit-maximizing ones—be they environmental sustainability, social responsibility, or other philanthropic activities—is to change the company's legal structure. In April 2010, Maryland became the first US state to create a new type of corporate structure known as “Benefit Corporation,” or “Benefit Corp.”108 Unlike standard corporations, with their legal obligation to shareholders’ financial interests, a Benefit Corporation requires companies to have a general public benefit purpose and allows the company to codify specific environmental and social goals, in addition to and sometimes at the expense of preserving investors’ capital and earning profits. Becoming a Benefit Corporation requires approval by the board of directors and shareholders; amendment of the company's bylaws; and reregistration of the entity. As of September 2017, Benefit Corporations could be formed in 33 US states109 including Delaware, which is the legal home of half of all publicly traded companies in the country.110 In 2016, Italy became the first country outside the United States to allow companies to register as Societá Benefit (a direct translation of the American term).111

The Benefit Corporation movement was spearheaded by B Lab, a nonprofit organization providing a certification known as “Certified B Corporation” or “B Corp” that is distinct from the legal benefit corporation status provided by states. Unfortunately, the “B Corp” term is often used interchangeably (and mistakenly) to refer to both. The B Corp certification is similar to other credence-based labels (see chapter 9), in which companies pay a fee, complete a self-assessment questionnaire, attain a sufficient score on the assessment, submit supporting documentation, agree to make certain public disclosures, and allow for random on-site reviews.112 As of July 2016, there were 4,099 Benefit Corporations,113 and, as of September 2017, there were 2,109 certified B Corps worldwide.114

The confusion and overlap between Benefit Corporations and B Corps is twofold. First, the B Corp certification requires that companies that have the legal option to become a Benefit Corporation must do so within four years of certification (or get re-certified).115 Second, Benefit Corporations must submit independent third-party reports about their environmental and social performance, and many have chosen B Lab's B Corp for this purpose. Note that only a formal, legal Benefit Corporation status protects managers from investors’ lawsuits related to having goals other than maximizing shareholders’ value.

Benefit Corporation status also provides protection for a company's environmental mission in the event of a hostile takeover bid. Without Benefit Corporation status, a buyout offer could tempt the shareholders and force the company into the hands of a “non-green” buyer. “The benefit corporation has allowed us to preserve our mission and culture against unsolicited tender offers. We don't have to worry that our board of directors might feel compelled to accept an offer that isn't in our overall best interests,” said Jenn Vervier, director of strategy and sustainability at New Belgium Brewing Company.116

The three green companies in this chapter have made somewhat different choices about Benefit Corporation status and B Corp certification. Patagonia became a certified B Corp in December 2011117 and filed for Benefit Corporation status for five of its corporations on January 1, 2012, the very first day the designation was available to California corporations.118 “Patagonia is trying to build a company that could last 100 years,” said founder Yvon Chouinard on the day Patagonia signed up. “Benefit corporation legislation creates the legal framework to enable mission-driven companies like Patagonia to stay mission-driven through succession, capital raises, and even changes in ownership, by institutionalizing the values, culture, processes, and high standards put in place by founding entrepreneurs,” he said.119

Dr. Bronner's converted to a Benefit Corporation in July 2015120 and became B Corp certified after that.121 The company's new bylaws formally expand the company's goals to include (i) spending on public awareness of environmental and social issues; (ii) the purchase of Fair Trade and organic ingredients; (iii) equitable employee compensation; and (iv) indemnification of shareholders’ activism on environmental and social issues. That last item essentially implies that the company can pay David Bronner's personal legal costs and fines when he tweaks the nose of US authorities over issues like hemp.

Seventh Generation is a founding member of the B Corp certification system. The company has been certified since May 2007122 and received its latest certification in 2015.123 However, Seventh Generation has not sought Benefit Corporation status, even though it has been available since 2011 in the company's home state of Vermont. Instead, the firm relies on clear language in the company's 2008 bylaws to define the firm's broader mission. The company has also gained outside investment from funds friendly to the company's mission, such as $30 million from Generation Investment Management Fund, which was cofounded by former US Vice President Al Gore.124

In September 2016, Unilever agreed to acquire Seventh Generation under terms that would maintain Seventh Generation's mission. “One of the things they really wanted to do is not impact or change who we are,” said John Replogle, CEO of Seventh Generation.125 Unilever took a similar approach when it bought Ben & Jerry's in 2000, allowing the ice cream maker to keep its corporate social and environmental mission. Unilever even supported Ben & Jerry's B Corp certification in 2012.126

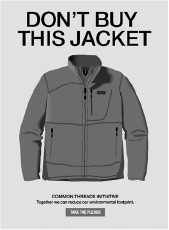

The financial performance of a company, as viewed by shareholders, is most readily measured by a company's market capitalization, which is generally a function of three major factors. The first is the company's net present value of all future profits, which itself is a function of the investors’ perceptions of the company's future revenues and costs. The second contributor to the company's total value is its assets, including tangible assets (such as buildings, inventory, cash, and payments owed by customers) and long-term intangible assets (such as patents, goodwill, and business methods). The third element, to be subtracted from the value of the company, is its liabilities, such as debts to bond holders, payments owed to suppliers, and money owed for lawsuits or other legal obligations. In general, shareholders prefer highly profitable, low-risk, fast-growing companies with valuable assets and minimal liabilities.

The environmental performance of a company, as assessed by the company itself or by NGOs and activists, is harder to measure and reduce to a single number. Not only are there many types of resource consumption, emissions, and toxicity impacts, but the impacts span the entire supply chain from suppliers to customers, around the world. There is no standard allocation mechanism related to environmental impact that can assign customer use or supplier footprint to a given company. Nevertheless, we aggregate all these dimensions in a notional “environmental impact” variable that reflects a company's net environmental effects.

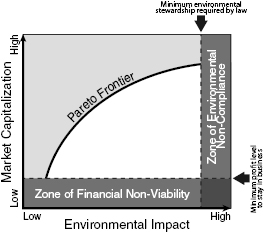

Figure 11.3 depicts a company's space of possibilities on these two dimensions: environmental impact and market capitalization. The white area is the space of known and feasible operating conditions. The coordinates of any point in that space represent the outcome of how the company operates in terms financial and environmental performance. Points in the shaded area represent levels of performance that the company cannot yet achieve with known actions and current technologies. Investors would prefer companies to operate as high as possible along the vertical axis—in other words, to maximize shareholders’ value. Environmental activists would like companies to operate as far to the left as possible on the horizontal axis—minimizing environmental impact.

Figure 11.3 The Pareto Frontier

All points on the boundary line between the white and shaded area in the figure—the Pareto frontier—reflect the best achievable performance levels of leading companies operating at the best possible levels of some mix of financial and environmental performance. Companies that have exhausted their low-hanging fruit of all the feasible initiatives face a trade-off of sliding one way or the other along the Pareto frontier. The slope of the frontier line reflects fundamental trade-offs between financial and environmental performance. The Pareto frontier is unique to each company because, in the short-run, it is a function of many contextual issues including the company's assets, the industry, its product designs, its supplier base, its distribution channels, and its customers.

Companies are not completely free to choose where to operate in the space depicted in figure 11.3. Every company faces constraints on both financial performance and environmental performance. In the long-term, businesses that consistently lose money are not economically viable. A company needs a minimum level of financial performance, over time, to cover expenses, attract capital, repay debts, compensate shareholders, accumulate reserves, and invest in its future. Green firms cannot continuously operate in the red. For example, Dr. Bronner's Benefit Corporation mission includes special public-benefit purposes that call for buying only sustainable ingredients “except when such certified ingredients are unavailable in sufficient quantities or are so cost prohibitive.”127 Similarly, Seventh Generation rewards employees for growth and profits, as well as sustainability.128

Likewise, the NGO attacks and government regulations cited in the first chapter illustrate that a company must attain some acceptable level of environmental performance. Governments can push companies toward lower environmental impact by tightening regulations. Most such actions are viewed by many companies as restricting their operating space, leading to inefficiencies and higher costs. Governments, however, have been willing to make this trade-off in the name of the common good when markets were perceived as failing to do it on their own.

In addition, as many of the examples throughout this book show, NGO attacks can be costly, motivating companies to be sufficiently environmentally responsible to forestall such potential attacks. Thus, both dimensions of performance have some bounds, which restrict the space of viable options, as shown in figure 11.4. (Of course, the lack of regulations or enforcement in some developing countries causes a corresponding absence of minimum environmental stewardship requirements. However, suppliers to Western companies may face customer requirements to limit environmental impacts.)

Figure 11.4 Meeting sustainability and financial goals

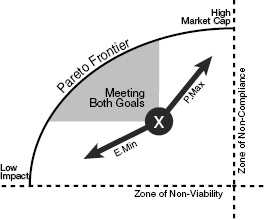

Most companies are not operating continuously along the Pareto frontier, because they are not doing all they can to achieve the best level of performance on either dimension. There are always more opportunities to reduce costs, mitigate risks, or boost revenues with new products or smart pricing. Analogously, most companies have further opportunities to improve supply chain resource efficiency, mitigate environmental risks across the life cycle, or boost the environmental qualities of their products. That is, most companies operate somewhere “below” the Pareto frontier at, for example, Point X in figure 11.5 and could move toward the Pareto frontier, improving either their financial performance, their environmental stewardship, or both. The direction of improving both dimensions (or improving one without degrading the other) is the zone represented by the grayed area in figure 11.5.

Figure 11.5 Options for improving performance

Figure 11.5 highlights the feasible region, depicting three different directions in which a company may choose to go. P.Max is the direction of maximizing profit at the expense of environmental performance. E.Min represents reducing environmental impact at the expense of profits, and the gray area represents directions that improve both goals.

Some companies, like those discussed in this chapter, move in the direction of the lower-left E.Min corner of the diagram—choosing higher environmental performance over higher financial performance. Benefit Corporation regulations provide a formal legal framework for companies to move “in the E.Min direction,” reducing environmental impact at the expense of financial performance. In contrast, other companies tend to move toward the top-left P.Max corner of the diagram by maximizing shareholders’ value while doing the minimum required to stay within the law and “out of trouble.” This is the case with many B2B enterprises, which, because they operate “behind the scenes,” are less susceptible to direct NGO pressure that can degrade consumer brands. Many of these companies will comply with the law and do what their customers require but no more. Of course, many other B2B companies, such as BASF, Siemens, and Alcoa, have significant environmental initiatives in place.

Numerous authors argue that profits and environmental sustainability are not at odds with each other and that companies can achieve both. This is certainly true if companies can pick performance improvements within the grayed region of figure 11.5, which allows them to move toward the Pareto frontier, improving on both dimensions. This is the case with initiatives motivated by eco-efficiency, eco-risk management, and/or eco-segmentation considerations. However, once companies reach the Pareto frontier, most of the low-hanging fruit, such as energy savings and waste reduction, as well as risk mitigation and new green product introduction, will have been harvested, and, without radical change, they will face unavoidable trade-offs between environmental and financial performance.

At that point, to further increase profitability, a company might, for instance, select factory sites or suppliers located in areas with lax regulations to avoid compliance costs. Alternatively, to further reduce impact, the company may need to place more onerous restrictions on suppliers, invest in expensive renewable energy or water conservation tactics, or design products with more sustainable but higher-cost materials. Pushing past the Pareto frontier to deliver both high financial performance and lower environmental impact requires a fundamental change.