St Peter ad Vincula, the ancient parish church of Stoke-upon-Trent, stands on one of the oldest sites of Christian worship in Staffordshire. There is thought to have been a church here since at least the seventh century. Early buildings were replaced by a stone church around AD 805, which was then altered and enlarged on several occasions. During medieval times the church and its rectory stood more or less on their own, somewhat removed from the main centres of population in Penkhull and Newcastle. Over the years, St Peter’s became the mother church of a huge parish, which included chapelries at Bagnall, Bucknall, Burslem, Clayton and Seabridge, Fenton, Hanley, Lane End, Newcastle and Norton-in-the-Moors. Several of these eventually became parishes in their own right.

Like many industrial towns, space in the pews grew short as the population expanded. A new church was begun in 1826 and consecrated in 1830. The interior features a large number of Minton Victorian memorial tiles around the walls, commemorating parishioners and others of note. The interior was remodelled in 1888, doing away with the three-decker pulpit and square family pews. The churchyard contains many memorials and the graves of several famous potters. Josiah Wedgwood was buried beneath the porch of the old church in a vault also containing the remains of his wife and son. A plain memorial marks his resting place. Re-erected fragments of the old church can still be seen in a garden to the south of the present building.

In 2005 St Peter ad Vincula was granted the status of a minster by the Bishop of Lichfield in recognition of its historic and civic status as the principal Anglian church of the city of Stoke-on-Trent.

Illustration of old Stoke church, which was demolished in 1829, from John Ward’s ‘The Borough of Stoke-upon-Trent’, 1843. (Courtesy of thepotteries.org)

There are only a handful of pre-1700 churches remaining within the Potteries. The west tower of St John the Baptist, Burslem dates from Tudor times and is the only complete Pre-Reformation structure in the area. First mentioned in 1297, St John served as a chapel-of-ease to Stoke-upon-Trent until 1809. Originally of timber, the nave was rebuilt in brick and tile in 1717 after a serious fire. In 1788, the church was extended by the addition of a chancel to create more seating, including a magnificent window in the Venetian style. Josiah Wedgwood was born in a nearby cottage and baptized at St John on 12 July 1730. Two other famous potters, William Adams and Enoch Wood, are both buried in the churchyard. Inside, a modern tablet commemorates members of the Adams family. Although still standing, St John’s no longer functions as an Anglican church.

Among other early churches, St John’s, Barlaston has a tower dating from the twelfth century with the remainder of the church having been rebuilt in 1888. St Mary & All Saints, Trentham also dates from the twelfth century and was extensively rebuilt in 1844. St Peter’s, Caverswall was founded in the thirteenth century and was subject to a major restoration scheme in 1880. St Bartholemew’s, in the once isolated village of Blurton, is one of the few English churches to be built during the reign of Charles I.

The eighteenth century saw the first great period of church building in the Six Towns, with the erection of St Bartholemew’s, Norton-inthe-Moors (1738), St John’s, Hanley (1737 and rebuilt 1788), and St John’s, Longton. At Longton, Anglicans used a chapel built in 1762, although it was initially registered as being for Protestant Dissenters. This became too small for the growing congregation and fell into decay before being rebuilt, as the Church of St John the Baptist, in 1795. The original red-brick nave and tower were supplemented by a new chancel in 1828.

Even with this additional capacity there was concern that large numbers of the urban poor and working class were not catered for by the Established Church. Like other industrial towns, the Potteries received substantial government funding during the 1820s and 1830s to found new places of worship. Arguably, the aim was also to pacify the new urban masses and dissuade them from revolution. Among these so-called Commissioners’ churches were St Mark’s, Shelton, St James the Less, Longton, Christ Church, Tunstall, and St Paul, Longport. Other churches were funded, either in whole or in part, through the generosity of local benefactors. Notable examples here are Holy Trinity, Hartshill (funded by Herbert Minton and designed by George Gilbert Scott in 1842, making it one of his earliest works) and St Thomas, Penkhull (also built by Scott at the expense of the Revd Thomas Webb Minton).

Fenton was the last of the Six Towns to receive its own Anglican place of worship. Until the mid-nineteenth century Fenton lay within the parish of Stoke. Christ Church, in what is now called Christchurch Street, was built in 1838–9, to a Gothic design by Henry Ward who also designed Stoke Town Hall. However, it had to be demolished because of subsidence and in 1890 was replaced by a second church, also called Christ Church.

GENUKI’s Staffordshire pages have photographs and old postcards showing many of the county’s churches (www.genuki.org.uk/big/ eng/STS/ChurchPhotos).

Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent Archives is the main repository for registers from Staffordshire parishes. Registers and other parish chest documents are listed by parish in the Gateway to the Past online catalogue. Original registers are available to view on microfilm at Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, with duplicates at Staffordshire Record Office. A full list of parish register holdings for Staffordshire, including registers held elsewhere is given in SSA Guide to Sources No. 1: Parish Registers and Bishops’ Transcripts. Bishops’ Transcripts were copies of parish registers made for the local bishop, in this case the Bishop of Lichfield. These records were at the Lichfield Record Office and can now be consulted at the SRO.

Under licence from the SSA, virtually all Anglican parish registers for Staffordshire are available online as part of the Staffordshire Collection at Findmypast. Approximately 200 parishes are covered, including all those within North Staffordshire. Coverage comprises baptisms, marriages and burials from 1538 (or whenever the individual registers commenced) through to 1900, and 1653–1900 for marriage banns, with digitized images of the original registers.

This online collection also includes marriage licences. These were administered by the church courts, the same bodies that handled wills and probate. A marriage licence could be obtained for a fee if a couple wished to waive the customary reading of the banns. There are several reasons why a couple might want to do so, such as the need to expedite the wedding date or if they were Nonconformist or Roman Catholic and did not attend the parish church. An allegation and bond had to be submitted in support of such an application. An allegation was a sworn statement prepared by the groom: it may state where the intended marriage was to take place and the groom’s occupation. The bond was intended to assert the authenticity and legality of the allegations, pledging a sum that would be forfeited if the documents proved inaccurate. The Staffordshire Collection on Findmypast has the Dioceses of Lichfield & Coventry Marriage Allegations and Bonds, 1636–1893 based on original documents held by the SSA.

Many registers for Staffordshire parishes may be accessed free of charge through the FreeREG project (www.freereg.org.uk). All of the Six Towns and most surrounding parishes are covered. New records, including for Nonconformists are continually being added.

Midland Ancestors maintains a series of marriage and burial indexes for Staffordshire including the Potteries, namely:

•Staffordshire Burial Index: Complete from the beginning of registers to 1837, containing all known recorded burials. See website for search procedures and fees. This is not to be confused with the similarly named Staffordshire Burial Index (which is actually a cemetery index) hosted by Midland Ancestors on behalf of the SSA (see below).

•Staffordshire Marriage Index: 1500s to 1837 including some Roman Catholic registers. See Midland Ancestors website for search procedures and fees.

•Staffordshire Monumental Inscriptions: See Midland Ancestors website for coverage (many parishes now available to download).

The Staffordshire Parish Register Society transcribes and publishes registers from Staffordshire parishes. Founded in 1901, its activities have been curtailed only by the two world wars and it is one of the few societies in existence still regularly printing parish registers in book form. Registers may be purchased via its website (www.sprs.org.uk) or the Midland Ancestors shop.

Other documents within the parish chest may name or have lists of parishioners. Those for Audley parish, for example, include a late eighteenth-century pew plan with the names of families [D4842/15/ 2/35-38].

The Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century caused a schism in English society. While some accepted the new Protestantism and its tenets – such as the Book of Common Prayer and the abolition of the Mass – others refused to comply. The West Midlands was one area where the Old Faith was kept alive. The Gunpowder Plotters of 1605 were famously led not by Guy Fawkes, as many believe, but by Robert Catesby, who is thought to have been born in Warwickshire. When the plot was discovered, Catesby and his co-conspirators (many of whom were from the Midlands) fled London and made a stand at Holbeche House in Staffordshire.

Six of the thirty-two stained glass windows in St Joseph’s, Burslem. The windows were designed by Gordon Forsyth and made by church members. (Friends of St Joseph’s, courtesy of thepotteries.org)

After a brief respite under the Catholic James II, the eighteenth century brought further oppression. Although the Toleration Act of 1689 guaranteed freedom of worship for dissenting groups, Roman Catholics were expressly excluded and Catholic repression continued. Some ceremonies were held in secret during this period but most Catholics were baptized and married in Anglican churches and buried in Anglican churchyards. It was not uncommon for the Anglican minister to mark an entry in the register with ‘papist’ or ‘recusant’. In the event of a Catholic marrying outside the Church of England, the authorities could prosecute the offending parties through the ecclesiastical courts.

The Catholic Relief Acts of 1778 and 1791 allowed new churches to be built. In the Potteries the first sign of resurgence was at Cobridge, where the Warburton and Blackwell families helped to finance the construction of a small Catholic chapel at the end of what is now Grange Street (then the lane leading to Rushton Grange Farm). This was in 1780, the same year as anti-Catholic protests in London that became known as the Gordon Riots. The disturbances so alarmed the congregation of Cobridge that they suspended construction for several months. The chapel was enlarged in 1816, at which time it was estimated to accommodate about 150 people.

This Catholic church, dedicated to St Peter, served the north of the district. Eventually, in 1895, a separate mission including Burslem, Smallthorne and Wolstanton was formed out of the Cobridge church operating from a building in Hall Street dedicated to St Joseph. The present Church of St Joseph was later built on an adjoining site.

Under the Catholic emancipation measures of the 1820s Roman Catholics were able to worship freely and more new churches began to appear. At Stoke, a mission was founded in 1838 by the priest from St Gregory’s, Longton, who had begun to say Mass at the home of a Mr Maguire in Whieldon Road. By 1841 Mass was being celebrated in a joiner’s shop in Liverpool Road, and in 1843 the venue was transferred to a new chapel in Back Glebe Street, dedicated to St Peter in Chains. The chapel continued to be served from Longton until the appointment of a resident priest in 1850. About this time the average attendance at Sunday Mass was 144, and by 1852 the Catholic population of the Stoke area was estimated at more than 500.

This chapel was structurally poor and far too small to accommodate the rapidly increasing membership. In 1852 the congregation purchased a new site at Hartshill and in 1854 the adjoining plot was acquired by Dominican nuns who had been searching for a suitable site in the Potteries for a new convent. Work began on the church and convent in 1856. Built in the Gothic style and dedicated to Our Lady of the Angels and St Peter in Chains, the new church opened its doors in Hartshill Bank the following year, at which point the old chapel in Back Glebe Street was sold. It is now a listed building.

Another notable Catholic church in the district is Sacred Heart, Jasper Street, Hanley, completed in 1891.

Staffordshire falls within the Catholic Archdiocese of Birmingham, established in 1911 (formerly the Diocese of Birmingham). Records from Staffordshire parishes (missions) are held at the Birmingham Archdiocesan Archives (BAA) at Cathedral House, Birmingham, next to St Chad’s Cathedral.

The BAA holds the episcopal and administrative records of the Midland District (1688–1840), the Central District (1840–50), the Diocese of Birmingham (1850–1911), and the Archdiocese of Birmingham (1911 to present). It is also the repository for all parishes in the Archdiocese, which comprises the ancient counties of Oxfordshire, Staffordshire, Warwickshire and Worcestershire. As well as baptisms, marriages and burials, these holdings include congregational records, showing whether an ancestor received confirmation or was a church benefactor. The BAA’s registers, including those for Staffordshire, have been digitized and are available on Findmypast (search under ‘England Roman Catholic Parish Registers’).

Other collections at the BAA cover the activities of a wide range of Catholic charities, societies and organizations. Of particular note are the records of the Catholic Family History Society (Midlands Branch), which was disbanded in 2007. There is an online catalogue (www. birminghamarchdiocesanarchives.org.uk). The registers of certain missions remain with their incumbents (details on the website).

Catholic Missions & Registers 1700–1880. Volume 2, The Midlands and East Anglia, compiled by Michael Gandy, gives details of Staffordshire Catholic mission registers (and sixteen other counties) and includes date coverage and location of registers.

The persecution of Dissenters (both Catholics and Nonconformists) from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries generated various genealogical records. Recusant Rolls list Dissenters and show the fines and property or land surrendered by the accused. Surviving lists have been published in the journal Staffordshire Catholic History at various dates and some original records are in the Quarter Sessions series [Q/RRr]. Returns of Papists are records from audits of Roman Catholics taken nationwide at various times, arranged in dioceses by town or village. Some returns simply record the numbers of Catholics and not their names. Again these have been published in Staffordshire Catholic History and its successor journal Midland Catholic History. Returns of Papists’ Estates are registers of Roman Catholics who refused to take oaths of loyalty after the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715 [Q/RRp].

The Midland Catholic History Society promotes the study of post-Reformation Catholic history and recusants in the Midland counties and issues a regular journal (http://midlandcatholichistory.org.uk). A detailed account of early Catholics, based on papers from the Bagot family collection, is given in ‘Roman Catholicism in Elizabethan and Jacobean Staffordshire’ by Anthony Gretano Petti (Collections for a History of Staffordshire, Fourth Series, Vol. IX).

The Potteries can claim to be one of the cradles of Methodism in Britain, having been associated with this Nonconformist tradition since its inception. John Wesley first preached in Newcastle-under-Lyme as early as 1738, the year of his conversion, and returned to the area many times. He had a great affection for North Staffordshire and was astounded by the economic and social changes unfolding before his eyes. In his journal for 8 March 1781, he noted: ‘I returned to Burslem. How is the whole face of this country changed in about twenty years! Since which, inhabitants have continually flowed in from every side. Hence the wilderness is literally become a fruitful field. Houses, villages, towns, have sprung up: and the country is not more improved than the people.’

During Wesley’s first visit to Burslem in 1760 a convert, Abraham Lindop, opened his cottage for services. The first Methodist chapel in the Six Towns was built at Hill Top four years later and Wesley preached there on six occasions. The entry in Wesley’s diary for 31 March 1784 records: ‘I reached Burslem, where we had the first society in the county, and it is still the largest, and the most earnest.’ By 1789 the Hill Top Chapel was the centre of a circuit with around 1,300 members.

In Hanley, Wesleyans opened their first chapel in 1783 in the area known as Chapel Fields, later Chapel Street, between Bryan Street and St John’s Anglican church. The pulpit was said to be too high for the building and only those at the front could see the minister’s face. For all its shortcomings, Wesley himself preached from that pulpit on 30 March 1784. In Stoke, a small group began to meet in an upper room in London Road around this time and went on to build their own Methodist chapel on land bought from master potter Thomas Wolfe. In 1801 the Burslem Methodists built Swan Bank Chapel and moved there from Hill Top and in 1804 the Newcastle circuit, which initially included Stoke, was formed.

Interior of the Bethesda Methodist Chapel, Hanley. Bethesda was the Conference Church for the whole of the Methodist New Connexion movement. (Courtesy of thepotteries.org)

Despite the burgeoning support, all was not well within the Methodist movement, however. In 1797 disagreements within the Wesleyan body nationally led some followers to secede and set up the Methodist New Connexion. Hanley’s society was devastated as many influential leaders left taking much of the congregation with them. As a result, membership of the Hanley Wesleyan society was reduced from 150 to 8 people almost overnight.

Several of this group went on to found the Bethesda New Connexion Methodist Chapel in Albion Street, Hanley, known as the ‘Cathedral of the Potteries’. The first chapel, erected in 1798, seated 600 and in 1811 a semi-circular rear extension was added to bring the capacity up to 1,000. The whole building was demolished in 1819 and a new chapel was built. Local architect Robert Scrivener added a stuccoed Italianate frontage with Corinthian portico in 1859. By this time Bethesda was one of the largest Nonconformist chapels outside London, attracting huge congregations and seating up to 2,000 people. The building is no longer used as a place of worship but The Friends of Bethesda hold regular open days (see www.bethesda-stoke.info).

It was against this background that a preacher called Hugh Bourne addressed a ‘camp meeting’ at Mow Cop, an isolated village on the Cheshire–Staffordshire border, 6 miles north of Stoke, on 31 May 1807. People had travelled from as far as Macclesfield and Warrington to hear him. For 14 hours Bourne preached and discussed, concluding only at 8.00 p.m. as darkness closed in on the proceedings. A second meeting was held at the same location three months later.

Bourne, a lowly born man from Bucknall who had quit his job as a wheelwright to become a roving preacher, rattled the Methodist authorities. They condemned the proceedings at Mow Cop as ‘highly improper in England’ and excluded Bourne from the Methodist circuit. Undeterred, Bourne and his followers organized under the name Camp Meeting Methodists. In 1811 Bourne was joined by another evangelist called William Clowes and his followers, and together the two communities adopted the name Primitive Methodists. This was intended to show that they wished to get back to Wesley’s primitive ways for street and field evangelism. The first Primitive Methodist Chapel was built in Tunstall that same year.

Hugh Bourne, founder of Primitive Methodism. (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)

By 1820 the Primitive Methodist movement had over 7,000 members and held its first conference in Hull. Churches were established up and down the country, as well as overseas. In 1841 a chapel was built on Mow Cop, which was subsequently given up in favour of a larger building nearby.

In the Potteries, nineteenth-century Methodism – in its various strands – appealed just as much to working class folk as to the prosperous middle classes. Miners, canal boatmen, shop assistants and potbank workers of every description attended the chapels and brought their children to be baptized there.

Although other forms of Nonconformism had a presence in the Potteries, none could rival the various strands of Methodism. Chapels run by other denominations known to have existed in the area include the Presbyterians at Newcastle-under-Lyme (1690, Unitarian from 1804); Baptists at Hanley (1789) and Burslem (1791); Independent (Congregationalists) at Hanley (1784); and Independent Methodists (not related to other chapels) at Burslem in 1837. A group known as the Sandemanians registered a building in Tunstall in 1812 and is said to have met for some time.

This popularity brought great wealth, allowing the construction of chapels that were not just places of worship but buildings of high architectural quality. In addition to Bethesda, notable examples are (or were): the Old Methodist Chapel, Epworth Street, Stoke (now demolished); and the Swan Bank (rebuilt in 1971), Bethel and Hill Top chapels, all in Burslem.

Following the schisms of the early 1800s, the theme during the early twentieth century was reunification. In 1907 the Methodist New Connexion joined forces with two smaller groups, the United Methodist Free Churches and Bible Christian Methodists to form the United Methodist Church. Then in 1932 the United Methodist Church merged with the Wesleyan Methodists and the Primitive Methodists to form the Methodist Church of Great Britain.

The Methodist Heritage Handbook provides information on historic Methodist locations in Britain, including Bethesda Chapel, Mow Cop & Methodist Chapel, and Swan Bank Chapel, Burslem (www. methodistheritage.org.uk). One of the sites listed, Englesea Brook Chapel and Museum, Crewe, tells the story of Primitive Methodism (www.engleseabrook-museum.org.uk).

Prior to 1754, Nonconformists could marry in their own chapels. Under Hardwicke’s Act of 1753 marriages had to take place in a licensed Anglican parish church before an Anglican minister. Quakers (as well as Jews) were exempt from the new law. After the introduction of civil registration in 1837, all religious denominations were free to hold legal marriage ceremonies and to keep their own registers. As very few chapels had their own burial grounds, individuals were either buried in the local Anglican churchyard or cemetery (some had areas set aside for Nonconformists) or were sent further afield to an independent chapel which did have a burial ground.

Primitive Methodist Centenary Meeting at Mow Cop, 1910. (Public domain)

The SSA holds the registers for many, though by no means all, Nonconformist places of worship in the county. At present, these registers are not in the Staffordshire Collection on Findmypast. The complexities in tracing Nonconformist places of worship are considerable. Nonconformist churches proliferated in huge numbers during the nineteenth century. In many Potteries communities it was not unusual to find a Wesleyan, a New Connexion/United Methodist and a Primitive Methodist chapel co-existing, probably with at least one other denomination as well. Many operated only for a few years, while others merged at later dates. Meanwhile, the same registers may have been used across a wide geographical area. SSA Guide to Sources No. 2: Non-conformist Registers lists those held by the county archive service.

The STCA has an especially rich collection of Methodist chapel and circuit records, 1799–1986 [SA/SM]. In addition to chapel registers, materials include minutes, financial records, Sunday school attendance lists, photographs and magazines: see the catalogue in the STCA Search Room for details. There is an additional series for the Bethesda Methodist Chapel that includes lists of church members, c. 1830–60 and of Sunday school attendees [SA/BE].

As with Catholic chapels, not all registers were surrendered to the Registrar General under the Non-Parochial Registers Commissions of 1837 and 1857. Across Staffordshire as a whole seventy-seven chapels deposited their registers. These are now available at TNA [in Classes RG 4 and RG 8] and through the BMD Registers (www.bmdregisters. org.uk), Ancestry and TheGenealogist websites. Staffordshire Record Society has published a list of dissenting chapels and meeting houses in Staffordshire between 1689 and 1853, compiled from the Return made to the General Register Office Under the Protestant Dissenters Act of 1852 (Collections, Fourth Series, Vol. III).

Other Nonconformist records which may be of value include minute books (some denominations had to apply to leave and re-join the church when they moved area), account books (records of payment for burial), lists of members, Sunday school admissions, monumental inscriptions, and magazines, newsletters and year books (which may include obituaries).

Methodist records are held at the John Rylands University Library, Manchester. These do not include local chapel registers but may be of help to those whose ancestors were Methodist preachers or prominent lay persons. The My Methodist History website has useful information and resources for tracing Methodist ancestors (www.mymethodist history.org.uk), with links to associated sites for Wesleyan Methodists, Primitive Methodists and Bible Christians. Its new resource, the Methodist Missionary Register, documents people who went to preach the gospel overseas. The very dated but still active North Staffordshire Methodist Heritage website contains a wealth of information on the Methodist movement in the area, including histories and photographs of chapels (www.rewlach.org.uk).

The Library of the Religious Society of Friends, at Friends House, Euston Road, London, is the main repository for researching Quaker ancestors and publishes several research guides (www.quaker.org.uk). Some copies are held locally at the SSA and at the Friends Meeting House (Bull Street, Birmingham); details at the Quaker Family History Society (www.qfhs.co.uk). The Library of Birmingham holds and is cataloguing the archives of the Society’s Central England Area Meeting, 1662–c. 2000.

For other Nonconformist sources see specialist guides such as Ratcliffe (2014) and Milligan & Thomas (1999).

During the nineteenth century a small Jewish community established itself in the Potteries. Initially, Hebrew services, in the Ashkenazi Orthodox tradition, were held in a private house in Marsh Street, Hanley. The community made efforts to find a more permanent and suitable home, leading to the purchase of an old Welsh Chapel in Hanover Street in 1873. In 1900 there were around thirty-five seatholders.

At a general meeting of the Congregation in 1902 the Chief Rabbi, Dr Alder, called for the erection of a new synagogue. Two adjacent properties in Birch Terrace, Hanley, were purchased and a new synagogue opened there a few years later. This remained in use until 2004, when the site was sold and the Congregation relocated to London Road, Newcastle-under-Lyme.

The latter is the location of the Jewish cemetery serving both Stoke-on-Trent and Newcastle. The land was given to the Jewish community in the 1850s by the Duke of Sutherland. Under Hebrew law land that is used as a burial ground must be bought, so a fee of £1 was charged. The first burial took place in 1886. In 1974 the cemetery chapel was demolished to make way for a road-widening scheme and in 2004 the replacement chapel was demolished to accommodate the relocated synagogue from Hanley.

Records of the Stoke-on-Trent and Newcastle-under-Lyme Congregation, as well as articles and other material relating to the Jewish community in the Potteries, may be accessed through the Jewish Communities and Records website, www.jewishgen.org/jcr-uk/ Community/stoke/index.htm. The STCA does not hold any Jewish registers of life events, however the general minutes of the Hebrew Congregation in Hanley, 1889–1916 and of the Stoke-on-Trent Congregation, 1948–73 on microfilm may contain the names of some members.

By the middle of the nineteenth century the burgeoning population was outgrowing the churchyards and calls were made for separate, municipally owned burial grounds.

In Hanley the issue got caught up in proposals to provide a public park. However, the Shelton-based potter John Ridgway argued that provision of a cemetery was more pressing. When the Borough of Hanley was incorporated in 1857, Ridgway was elected its first Mayor and helped to form a Burial Board Committee. The following year the Committee secured a site in Shelton and a competition was launched for the laying out of the cemetery grounds and the design of new chapels. Hanley Cemetery opened in 1860 and the populace had to wait until 1897 for the opening of Hanley Park.

Longton launched a design competition in 1872, prior to the opening of Longton Cemetery in 1878. The original site covered approximately 7.4 hectares (about 21 acres) and has been extended several times. Tunstall Cemetery was also laid out during this period, on part of Tunstall Farm, and opened in 1868. Burslem Cemetery opened in 1879 and covers approximately 11.4 hectares (about 28 acres). It was intended as ‘a recreation park, to be used for walking, riding and driving’, as well as a cemetery, and at least a third of the land was taken up with the lodges, chapel, walks and drives. Only about 5½ acres was laid out for burials.

Stoke Cemetery, known as Hartshill, opened in 1884. The site chosen was not a popular one because it was so far away from the town, between the villages of Hartshill and Penkhull. There was also public disquiet about the choice of architect and the number of chapels. Without consulting ratepayers, the Council accepted a petition from leading Anglicans that there should be one chapel ‘for church people’ and another for ‘dissenters’ and agreed to build two chapels.

The last of the Six Towns to get its own cemetery was Fenton. This was laid out in 1887 on a 16½-acre site in the north-east of the town, on sloping ground at the rear of Fenton Park. This too had separate chapels for Anglicans and Nonconformists.

Today, there are nine cemeteries administered by Stoke-on-Trent City Council. Opening times are given on the Council website, which also has a list of closed churchyards across the Six Towns (www.stoke. gov.uk/directory/26/cemeteries_and_churchyards). Other municipal cemeteries in the district include those at Newcastle-under-Lyme (opened 1866), Silverdale (1886) and Knutton (1888).

Burial records from all of the city’s cemeteries are kept at Carmountside Cemetery and Crematorium. These are arranged in date order and there is no name index. Enquiries and search requests should be sent to the Carmountside Cemetery Office at the address given in Appendix 2.

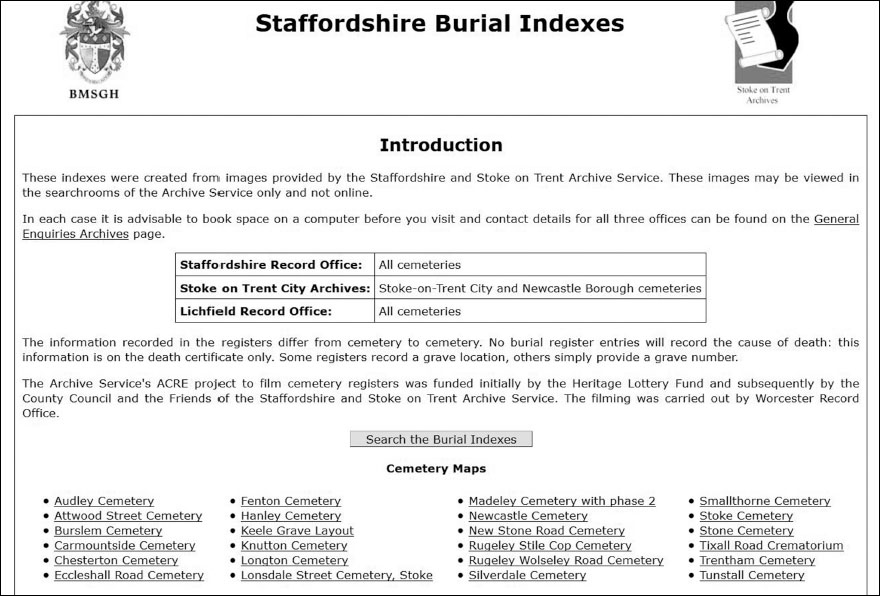

The Staffordshire Burial Index website.

Midland Ancestors maintains the Staffordshire Burial Index, an index of burials created from cemetery registers held by the SSA. The transcripts may be searched online at www.bmsgh.org/burialsearch/and the original images may be viewed in the search rooms at the STCA or SRO. The information recorded in the registers differs from cemetery to cemetery: some record a grave location, others simply provide a grave number.

Parish and cemetery burials in Staffordshire are listed in the National Burial Index from indexes compiled by Midland Ancestors; it is available as a DVD and online at Findmypast. The Federation of Family History Societies website has a list of burial grounds covered (www.ffhs.org. uk/burials/sts3.php).

Over the last forty years Midland Ancestors volunteers have transcribed the monumental inscriptions (MIs) from graves, tombstones and memorials across Staffordshire. These transcriptions have been published and many are now available either on CD-ROM or as downloads. The indexes are also open to postal and/or email enquiries. Copies of these MIs may be consulted at the Midland Ancestors Reference Library (Birmingham), the SSA search rooms, and the Society of Genealogists in London.

Other sources for information on deaths include newspaper announcements and obituaries, and wills (see Chapter 1).

The Potteries’ association with the labour movement goes back to the very beginnings of organized labour and the political reform movement known as Chartism. Under the Reform Act of 1832, Stoke-upon-Trent became a Parliamentary Borough and was able to return two Members of Parliament. However, the Act only went part of the way to meeting the demands of political reformers and during the 1830s a grassroots movement evolved around a wider campaign for political and social reforms. They unveiled their demands in a ‘People’s Charter’, launched in London in 1838, and hence became known as the Chartists.

The People’s Charter had six main demands: the vote for all men aged over 21, the abolition of a property qualification, secret ballots, fixed elections, equal sized constituencies and salaried Members of Parliament. A national petition in support of the Charter attracted over 1 million signatures. Mass rallies were held across the country, some of which became violent. The Hanley & Shelton Political Union, established in 1838, was one of many organizations to espouse the Chartist cause. It organized a Grand Meeting in the Potteries on 17 November 1838.

The Potteries avoided the more severe expressions of discontent over the Reform Act seen elsewhere. However, the election of John Davenport, the Longton pottery manufacturer, as one of the first MPs did not prove popular. He was not enthusiastic about the Reform Act and was a severe employer. A contemporary account recorded that ‘on the day of nomination, at Stoke, whilst Mr Davenport was addressing the electors, missiles were profusely thrown into the hustings, which inflicted some severe contusions on several gentlemen, and drove the candidates and their friends to seek shelter in the adjoining Town Hall’. There was further trouble in 1837, when Davenport was again elected to Parliament. In 1841, the crowd directed its ire towards Mr Copeland, another pottery manufacturer who was standing for the Conservative Party. According to historian John Ward: ‘The Liberal populace then seized and destroyed the banners of the opposite party, routed them in all directions and proceeded to Stoke to demolish the windows of Mr Copeland’s manufactory, which they effectively accomplished, as well as the windows of several of his new houses adjacent’.

The most notorious Chartist-related incident in North Staffordshire was in August 1842. A group of workers in the potteries and pits around Hanley were involved in an industrial dispute with their employers and this situation became caught up in wider calls for a general strike in support of the Charter. On Monday, 15 August, Chartists and miners declared that they would join together and ‘all labour cease until the People’s Charter becomes the law of the land’. The following day, 16 August, the strikers marched on Burslem amid an increasingly inflamed situation. Soldiers were called from Newcastle to disperse the mob, resulting in more than 270 arrests. At their trials the following October, 54 North Staffordshire men were sentenced to transportation and a further 146 to imprisonment with hard labour. The episode scared working class communities in the Potteries for many years.

One of those imprisoned was Joseph Capper, a blacksmith and preacher from Tunstall. Although he preached a message of peaceful resistance and had not been present at the riot, he was widely seen as one of the ring-leaders and so singled out by the authorities. He served two years in prison and is recognized as one of the key figures in both Chartism and Primitive Methodism in North Staffordshire.

For further details of Chartism see Anderson (1993) and the specialist website www.chartistancestors.co.uk.

The earliest record of trades unionism among the pottery workers of North Staffordshire can be found in a 1792 newspaper report that records their efforts to combine for better wages. This was a short-lived endeavour and it would take another eighty years for trades unions to become fully established within the pottery industry.

Many of workers’ early efforts to form unions were small, specific to particular specialist trades and often brief. The Union of Clay Potters was started to represent the skilled workers handling the early stages of manufacture, and the Pottery Printers Union spoke for those decorating the finished product. In 1825, these two unions called the first official strike in the Potteries but it was soon defeated and the union destroyed. A further attempt to create a China and Earthenware Turners Society in 1830 fared no better.

The following year the National Union of Operative Potters was established, with the aim of recruiting all those working in the industry, including in other parts of the country. A key cause of complaint was the truck system, whereby employees were paid in vouchers or tokens that they could only spend in their employers’ shops. Although membership grew to 8,000, the union was again defeated in strikes in 1834 and 1836 and ceased to operate. During the 1840s, such trades unionism as existed in the industry was largely non-confrontational. The United Branches of Operative Potters, founded in 1843, opposed strikes, but proved no more resilient than its predecessors, declining over the following decade to a small local organization. It was revived briefly as the National Order of Potters in 1883 but lasted only a few years. By mid-century, trades-union activity had subsided.

Enduring trades-union organization arrived in the Potteries with the revival of the industry in the 1870s. Yet many of the organizations established over the following twenty years were limited in both numbers and ambition. Among those that formed and quickly disappeared during this period were the Amalgamated Society of Pottery Moulders and Finishers, founded in 1893 and dissolved in 1900; the China Earthenware Gilders Union, which lasted just three years from 1891–4; and the Cratemakers Society, founded in 1872 but no longer in existence by the end of the decade. Many pottery unions struggled to recruit, especially away from their Staffordshire heartlands.

At the beginning of the twentieth century workers’ representation was still highly fragmented. There were more than seventy major pottery manufacturers in Stoke-on-Trent, each with hundreds of unique trades and each trade having its own worker representative. In 1906 the three biggest unions merged to form the National Amalgamated Society of Male & Female Pottery Workers. By 1921 most of the remaining unions had joined the renamed National Society of Pottery Workers (NSPW). It had around 60,000 members throughout the country, most of whom worked in Stoke-on-Trent. Many of them had been recruited by the Society’s charismatic general secretary, Sam Clowes. In 1970 the NSPW became the Ceramic & Allied Trades Union, which has since been absorbed into the modern trades-union movement.

The Hobson Collection at the STCA comprises a wide range of materials relating to the history of trades unionism in the pottery industry assembled by researcher Stephen Hobson [PA/HOB]. While there are few records relating to individuals, the collection provides valuable social context on working and welfare issues in the sector from the late nineteenth century. Materials include industry wages and prices agreements, papers of unions and employers’ organizations, and newspaper cuttings.

The Working Class Movement Library in Salford holds the archives of the Ceramic & Allied Trades Union and its predecessor organizations, including membership returns, newspaper cuttings and wage agreements (www.wcml.org.uk).

The Modern Records Centre at the University of Warwick has substantial collections of trades-union and labour movement archives. These files may include details such as membership lists, contributions books, minutes of branch meetings, wage rates, company files, and accident and mortality reports. The holdings range from long-defunct local organizations; to Midlands branches of early national unions; to the national archives of current-day trades unions.

Crail (2009) and that author’s specialist website www.unionancestors.co.ukhave further details on tracing trades-union ancestors.

Anderson, Robert, The Potteries Martyrs: Chartism in North Staffordshire (Military Heritage Books, 1993)

Burchill, Frank and Richard Ross, A History of the Potters’ Union (Ceramic & Allied Trades Union, 1977)

Crail, Mark, Tracing Your Labour Movement Ancestors (Pen & Sword, 2009)

Greenslade, Michael, Catholic Staffordshire (Gracewing, 2006)

Milligan, E.H. and M.J. Thomas, My Ancestors Were Quakers (Society of Genealogists, 1999)

Ratcliffe, Richard, Methodist Records for Family Historians (Family History Partnership, 2014)