The area we now know as Stoke-on-Trent lies in a shallow depression on the south-western edge of the Peak District. The landscape is characterized by high plateaus punctuated by a series of steep ridges and river valleys. To the west, the industrialized and densely settled conurbation forms a boundary with the sweep of the Cheshire, Shropshire and Staffordshire plain. To the south, the incized landscape gives way to rolling Midlands countryside in the Trent and Dove valleys. At the eastern flank, the Churnet Valley runs through smoothly undulating upland pasture linked by short, steep, wooded valleys known locally as ‘cloughs’. The river that gives its name to the city, the Trent, traverses from north to south. From its source on the southern edge of Biddulph Moor, a few miles north of the city, the Trent flows through Stoke merging with the Lyme, Fowlea and other streams that drain this area of North Staffordshire.

Archaeological finds show that this part of the north Midlands has been populated for thousands of years. Caves in the Manifold Valley were occupied during the Palaeolithic era, probably on a seasonal basis. Barrows on prominent hilltop sites, such as the Bridestones on the Cheshire border, suggest that the area was being farmed by the Neolithic or Bronze Age (c. 3000 BC). Names such as Trent, Lyme (as in Burslem) and Penkhull are Celtic in origin and suggest that this was an important place of settlement in pre-Roman and Roman times. The Romans built several roads across North Staffordshire and established a fort at Chesterton. Near this road at Trent Vale, on the banks of the Trent, a Roman pottery kiln has been found: possibly the first instance of pottery-making in the area.

The discovery of the Staffordshire Hoard in a field near Lichfield is a reminder that the Kingdom of Mercia was home to a vibrant culture during the period known as the Dark Ages. Saxon crosses at Stoke and Leek testify to the strong Christian heritage in the period before the Norman Conquest. The name ‘Stoke’ is Old English for ‘place’ and is especially used of a ‘holy place’, again suggesting very early Christian connections. Although there is evidence of pottery being made during medieval times, the wares were crude and utilitarian, showing little promise of the glory that was to come.

For family history purposes, we can think of North Staffordshire in terms of three distinct localities: the Six Towns that eventually joined together to form the city of Stoke-on-Trent; the ancient borough of Newcastle-under-Lyme; and the hinterland towns and villages of the Staffordshire Moorlands from which many people migrated to find work in the rapidly growing industrial centre on their doorstep.

The city of Stoke-on-Trent came into being in March 1910 through the federation of six neighbouring towns. These were the boroughs of Burslem, Hanley, Longton and Stoke, plus the districts of Fenton and Tunstall. Stoke was chosen as the administrative centre, despite Burslem and Hanley being better established. The constituent towns still retain a strong sense of identity and many locals identify more with their hometown while referring to ‘the Potteries’ for the wider administrative unit.

Broadly speaking, the city has developed along a linear axis, from Tunstall in the north, through Burslem, Hanley and Stoke clustered in the centre, to Fenton and Longton on the southern fringes. During the nineteenth century each of these towns displayed great civic pride, as attested by the array of town halls, parks and other civic amenities that sprang forth.

BURSLEM

Although not the first of the six to be incorporated, Burslem was the largest town in the Potteries and the first to develop with the onset of the Industrial Revolution. As early as the seventeenth century Burslem was noted for the quality of its pottery production. Thus, it became known as ‘The Mother Town of the Potteries’. It was no coincidence, perhaps, that the greatest exponent of the potters’ art, Josiah Wedgwood, was born here.

Burslem Old Town Hall and the bottle kiln of the Central Pottery, 1967. (Courtesy of thepotteries.org)

In the Domesday Survey Burslem appears as ‘Bacardeslim’ and frequent references (under various spellings) are found in records and charters throughout the medieval period. The Church of St John the Baptist served as a chapelry to Stoke for many years, until Burslem became a separate parish in 1807. During the eighteenth century Burslem became closely associated with Nonconformism and John Wesley visited the area frequently.

Following the opening of the Trent & Mersey Canal the manufacturing district of Longport became an important trading centre with many wharfs from where boats dispatched finished wares the length and breadth of the canal network. Other nearby villages, which eventually became populous suburbs, included Brownhills, Sneyd, Hulton Abbey and Cobridge. Burslem was incorporated as a borough in June 1878.

FENTON

Historically, Fenton consisted of the two townships of Great Fenton (also known as Fenton Culvert) and Little Fenton (or Fenton Vivian). In 1832 the boundaries were formed to the west by the River Trent, by the Cockster Brook to the south and the east (the common boundary with Longton), while the northern boundary adjoining the township of Botteslow followed an irregular line. Little Fenton was the site of a medieval manor house and the manor is listed in Domesday as thane land amounting to about 30 acres held by the Saxon Alward. The Hearth Tax returns of 1666 list seventeen people in Fenton Vivian and sixteen in Fenton Culvert liable to pay the tax. By 1775 the population was strung out along the main Newcastle to Uttoxeter road, with separate settlements at Lower Lane, Lane Delph and Lane End. Fenton developed more slowly than the other towns: as well as pottery manufacture, mining and iron working were important industries.

HANLEY

Hanley grew up as two separate hamlets about half a mile apart, known as Hanley Upper Green (centred on the junction of Keelings Lane and Town Road) and Lower Green (now the Market Square). By the mid-sixteenth century the area was known as Hanley Green. By 1775 the built-up area had spread westwards into Shelton township and there was continuous building along what are now Town Road, Old Hall Street, Albion Street and Marsh Street.

The growth of the town is reflected in the building of the church in 1738, its extension in 1764 and its rebuilding in 1787–90. By the 1790s Hanley, though still smaller than Burslem, was described as ‘an improving and spirited place’; it was, however,‘built so irregularly that, to a person in the midst of it, it has scarcely the appearance of anything beyond a moderate village’. In the 1830s Hanley was considered ‘a large modern town’, the largest in the Potteries and the second in Staffordshire. Its streets were ‘generally spacious and well paved’, its houses were of ‘neat appearance, and some of them, as well as the public edifices . . . spacious and elegant’. On the other hand, much of the town was overcrowded and insanitary. In 1850 it was noted that ‘the principal streets have some good shops; and there has been lately finished a range of shops far above the standard of everything else in the Pottery district’. A planning official in the 1960s described the centre of Hanley as ‘an archipelago of island sites’ and the town’s village roots are preserved in the irregular layout of the present-day town centre.

LONGTON

Longton (meaning ‘long village’) is the newest of the Six Towns and was originally laid out as an agricultural village in the thirteenth century. It was at the end of a lane which ran from Tunstall and hence was known originally as Lane End, and colloquially as ‘Neck End’. Coal mines and iron works were the main industries but the building of the Newcastle to Uttoxeter turnpike in 1759 and shortly after the Trent & Mersey Canal brought the pottery industry to the town. Later its position on the Stoke and Derby branch of the North Staffordshire Railway (NSR) also served it well. Numerous small pot works gave the new town a distinctive irregular appearance with pot banks lining the main streets jumbled in and around the workers’ houses. During the nineteenth century it became established as one of the most important centres of the pottery industry, in particular for the production of bone china. But its huge concentration of ovens and position in a slight hollow earned Longton the reputation of being highly polluted.

STOKE

The town of Stoke-upon-Trent (generally known simply as Stoke to distinguish it from the city of Stoke-on-Trent) is the oldest of the six communities. The ancient parish of Stoke spanned a huge area, from Whitmore in the west to Bagnall in the east, and from Burslem in the north to Longton in the south. These outlying districts had their own chapelries and maintained their own parish registers. A series of Acts of Parliament in 1807, 1832 and 1889 saw the various chapelries split off into separate parishes.

Curiously, Stoke itself was for centuries little more than a church and a few houses. It is recorded as such in the Domesday Survey of 1087 and remained virtually unchanged until the arrival of the turnpike roads and the Trent & Mersey Canal in the eighteenth century. The church served the neighbouring village of Penkhull, a hilltop settlement which remained an important township into the nineteenth century. Pigot’s Directory of Staffordshire 1841 notes that Stoke:

owes its increase in population and opulence to the establishment of numerous potteries, for which its situation, on a navigable river and a great canal, renders it favourable, and for which it has for many years been distinguished. The town contains many handsome houses, commodious wharfs and warehouses, and extensive china and earthenware manufactories, and is deemed the parish town of the Potteries.

The towns of Stoke, Penkhull and Boothen were incorporated as the Borough of Stoke-upon-Trent in January 1874.

TUNSTALL

Tunstall is the most northern town of the city. It stands on a ridge surrounded by old tilemaking and brickmaking sites, some of which probably date back to the late Middle Ages. Historians have found that iron was being produced here as early as 1280. By the sixteenth century Tunstall comprised about 100 acres of land contained within six open fields, which were later enclosed. In 1795 it was described as the ‘pleasantest village in the pottery’. The neighbouring village of Goldenhill existed by 1670 and by 1775 was almost as large as Tunstall, becoming a major centre for the iron industry as well as pottery manufacture. By the time of the cutting of the Trent & Mersey Canal mining had also become established at Goldenhill. The canal passes within ½ mile of Tunstall village and the Harecastle Tunnel, which runs nearly 2 miles underground, is nearby.

Strictly speaking, Newcastle-under-Lyme is not and never has been within the Potteries. Its origins are much older, having grown up around the twelfth-century castle which stood in an extensive tract of water fed by the Lyme Brook and other streams from the surrounding hills. The presence of a permanent garrison attracted traders and craftsmen, and there was a market by at least the early 1200s. A Guildhall was built and the town is thought to have been granted borough status around 1172–3.

The marketplace Newcastle-under-Lyme, c. 1890 showing the Guildhall. (Public domain)

The town blossomed further during the Georgian period, due mostly to its strategic position on both north–south and east–west coaching routes. The High Street contained several important coaching inns by the middle of the eighteenth century. Surrounded by a large agricultural district, Newcastle became a key centre for trading in cattle. Mining also sprang up in the districts of Silverdale and Apedale to the west. Although there was a church here from the thirteenth century, it was for many years a chapel dependent upon the parish church at Stoke-upon-Trent. The current Church of St Giles dates from the 1870s and was designed by Sir Gilbert Scott.

Newcastle largely escaped the industrialization that beset its neighbours during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and today may be regarded as a suburb of Stoke-on-Trent.

Although never administratively part of Stoke-on-Trent, the people of the Potteries have always felt intimately connected with the Staffordshire Moorlands. This rugged upland on the district’s eastern flank was where many of their ancestors originated before moving to the rapidly expanding pottery towns in search of work. The agricultural economy, centred on the market towns of Leek, Cheadle and Biddulph, helped to feed the burgeoning population down the valley. Once working conditions began to improve and people were granted more time off, rural locations such as the Churnet Valley and Rudyard Lake provided much-needed recreation for the Potteries’ hard-pressed workers.

Historically, the present-day Staffordshire Moorlands area was mostly contained in the hundred of Totmonslow, one of Staffordshire’s ancient divisions. During the eighteenth century the area underwent its own mini industrial revolution, with textile mills being established at Leek, Cheadle and other locations: silk working in particular came to dominate. Coal mining was also an important industry.

Most of the district is over 180m (600ft) above sea level and Flash, at 463m (1,518ft), is reputedly the highest village in Britain. Much of the area now falls within the Peak District National Park.

The growth of the Potteries is intimately bound up with the growth of the ceramics industry. As industry adopted the factory system, ever larger numbers of people were required living closer to hand. Higher wages enticed people from the rural areas into the new industrial and urban areas that were clustered initially around the canals and coalfields, and later the railways.

By the nineteenth century the villages of the Potteries had grown into sizeable towns, of which Burslem was the largest. Calls for them to be amalgamated into one administrative unit began as early as 1817. Administrative rationalization began in 1857, when the towns of Hanley and Shelton were combined into the Borough of Hanley. In 1865 Longton and Long End became the Borough of Longton; and in 1874 the towns of Stoke, Penkhull and Boothen were brought together as the Borough of Stoke-upon-Trent (generally known as Stoke). The remaining towns, Fenton and Tunstall, gained urban district status in the 1890s. In 1910 the rationalization process was completed when all six towns were brought together to form the County Borough of Stoke-on-Trent. The borough gained city status in 1925.

Stoke-on-Trent’s borders have expanded on a number of occasions since then. The main change came in 1922 with the addition of areas to the south and east of the city. This comprised all or part of the civil parishes of Smallthorne, Caverswell, Stone, Trentham, Hanford, Bucknall, Norton, Chell, Newchapel and Milton.

Reliable population statistics are hard to come by. According to one estimate, in 1738 there were as few as 4,000 people living across the 6 districts (John Ward, The Borough of Stoke-upon-Trent, 1843). The first census in 1801 recorded a population of more than 26,000 and by the time of the 1841 census this had more than doubled, to around 63,000. Official statistics for the Stoke-on-Trent local authority area cite slightly different figures for the historical population, partly due to boundary changes over the years. It is these that are quoted in Table 1.1 overleaf.

Table 1.1: Population of Stoke-on-Trent Urban Area

| Year | Population, 000s |

| 1801 | 17.5 |

| 1811 | 23.7 |

| 1821 | 29.8 |

| 1831 | 42.7 |

| 1841 | 55.5 |

| 1851 | 59.5 |

| 1861 | 74.2 |

| 1881 | 121.0 |

| 1891 | 139.5 |

| 1911 | 257.5 |

| 1931 | 272.1 |

| 1971 | 260.0 |

| 2011 | 249.0 |

Source: GB Historical GIS/University of Portsmouth, A Vision of Britain through Time. www.visionofbritain.org.uk/unit/10217647/cube/TOT_POP.

When it comes to using the censuses, the situation for North Staffordshire is very much ‘business as usual’; which nowadays, of course, means searching online. All of the publicly available censuses, 1841–1911, are available through commercial websites as well as being free to access at FamilySearch. The FreeCEN project is aiming to provide free online access to UK nineteenth-century census returns (https:// freecen2.freecen.org.uk). At the time of writing, coverage for North Staffordshire is limited to 1861 and part of 1891; check the ‘Database Coverage’ page for updates. Stoke-on-Trent City Archives has various legacy products and indexes on microfiche, CD-ROM and hard copy but these are much inferior to online alternatives.

The four censuses taken prior to 1841 (i.e. 1801–31) generally listed only the head of the household rather than the entire population. Coverage for these pre-1841 listings is extremely patchy: the only ones known to survive for North Staffordshire are for Biddulph, 1801 [SRO: D3539/1/48] and Newcastle-under-Lyme, 1811 [SRO: D3251/9/1]. In addition, Staffordshire Record Office has earlier ad hoc population listings for Stoke-on-Trent, 1701 (gives all names and ages); and Biddulph, 1779. A List of Families in the Archdeaconry of Staffordshire is a survey of 1532–3 listing over 51,000 names for mid-and North Staffordshire; it has been published by the Staffordshire Record Society (Collections, 1976). Chapter 8 has further details of these early listings.

At the introduction of civil registration on 1 July 1837, England and Wales were divided into a series of registration districts based on the Poor Law Unions (PLUs) introduced a few years before. North Staffordshire comprised six registration districts, each with several sub-districts:

1.Stoke-upon-Trent: covered the heart of the urban area, encompassing the parishes of Bagnall, Fenton, Hanley, Longton, Stoke Rural and Stoke-upon-Trent.

2.Wolstanton: covered ten parishes to the north and west of Stoke-upon-Trent, including Burslem, Chell, Chesterton, Tunstall and Wolstanton.

3.Newcastle-under-Lyme: covered around twenty parishes in northwest Staffordshire. There were sub-districts at Audley, Kidsgrove, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Whitmore and Wolstanton.

4.Stone: was a large district to the south of Stoke-upon-Trent that included the parishes of Barlaston, Blurton, Hanford and Trentham. It was abolished in 1937 to become part of Stafford registration district.

5.Cheadle: covered parishes to the east of Stoke-upon-Trent, including Caverswall and Cheddleton. It was abolished in 1974 to become part of Staffordshire Moorlands and East Staffordshire registration districts.

6.Leek: was a very large registration district to the north-east of Stoke-upon-Trent covering more than thirty parishes, the closest to the Potteries being Norton-in-the-Moors and Endon. It, too, was abolished in 1974 to become part of Staffordshire Moorlands registration district.

Jurisdictions within the main urban area have shifted several times over the years due to administrative and boundary changes. The original Stoke-upon-Trent and Wolstanton registration districts were abolished in 1922 to become part of a single Stoke & Wolstanton registration district. This, in turn, was abolished in 1935 with the creation of the Stoke-on-Trent and Newcastle-under-Lyme registration districts. The latter subsequently became part of the Staffordshire registration district. UKBMD (www. ukbmd.org.uk/genuki/reg) has further details of the evolution of registration districts within the Potteries and surrounding areas.

Civil birth, marriage and death registers for the historical registration districts referred to above are now held either by Stoke-on-Trent Register Office at Hanley Town Hall (for areas now within the city boundary, see www.stoke.gov.uk/info/20011/births_marriages_and_ deaths), or Staffordshire County Council Registration Service (other areas including Newcastle-under-Lyme and Staffordshire Moorlands, see www.staffordshire.gov.uk/community/lifeevents/certificates/ certificates.aspx). Both services offer an online ordering facility for purchasing certified copy certificates. Staff at Stoke-on-Trent will also undertake searches in the indexes for a period of three years but only where accurate details are provided. See council websites for opening hours and fees.

Copies and transcriptions of the General Register Office (GRO) indexes are widely available online, including on non-commercial sites such as FamilySearch and FreeBMD. The STCA has a copy of the GRO indexes for the whole of England and Wales on microfiche for 1837–1960.

The indexes held by the local civil registration service are often more accurate and more complete than the central indexes compiled by the GRO. Family history societies within Staffordshire are collaborating with the local registration services to transcribe their indexes and make them freely available online. The project is ongoing and there is already good coverage for all areas within the former registration districts of Stoke-on-Trent and Newcastle-under-Lyme (www.staffordshirebmd.org. uk). The site has the addresses of all register offices in Staffordshire and details of how to order certificates.

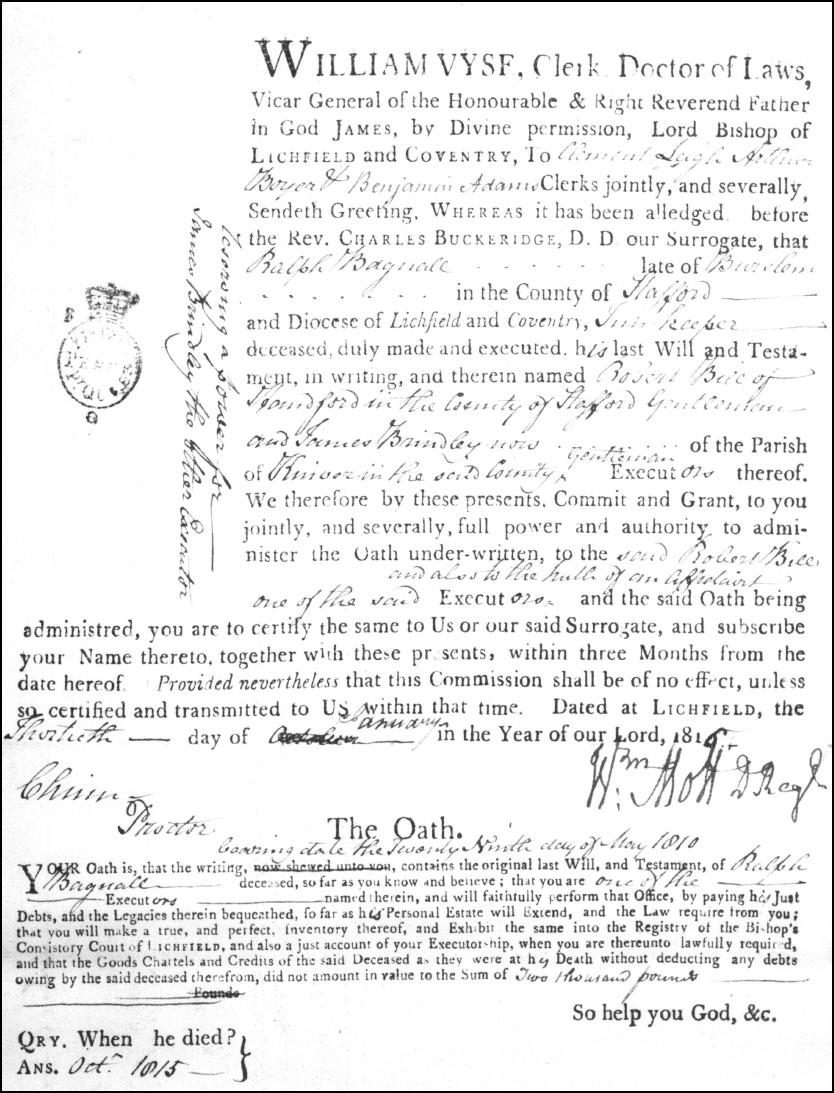

Probate is the general term for the management of a deceased person’s estate. It is a legal process during which a will has to be proved (meaning ‘approved’) by persuading a court that it is valid and has not been superseded. Once the court is satisfied of these conditions then probate is ‘granted’. Responsibility for carrying out the terms of the will falls to the executor (or executrix if female) appointed by the deceased as detailed in the will. Letters of Administration, or ‘Admons’, are issued when a person dies intestate (i.e. without leaving a will). Historically, other documents that may occur in the context of probate are inventories of the deceased’s personal possessions (a statutory requirement between 1529 and 1782); and papers relating to death duties and other taxes. Raymond (2012) has further background on the history and purpose of probate records.

Executor’s oath from the probate of Ralph Bagnall of Burslem, granted at the Lichfield Consistory Court, 9 April 1816. (Staffordshire Collection, FindMyPast)

Since 1858, probate for England and Wales has been administered centrally through the Principal Registry of the Family Division. The index to these cases, known as the National Probate Calendar, is available to search free of charge at the Government’s Probate Search Service website (https://probatesearch.service.gov.uk/#calendar). There are separate databases for 1858–1996, 1996 to present, and soldiers’ wills. Copies of these wills can be ordered at the same site and currently cost £10 each. The National Probate Calendar is also available via Ancestry (1858–1966) and Findmypast (1858–1959).

Before 1858 probate was proved in ecclesiastical (church) courts. The whole of Staffordshire was within the Diocese of Lichfield & Coventry. The Bishop of Lichfield & Coventry had general jurisdiction over probate within this area, which was exercised through the Lichfield Consistory Court (LCC). Unlike many dioceses, there were no archdeaconry courts and the LCC covered the whole diocese. Some areas, known as peculiar jurisdictions or peculiars, were exempt from the bishop’s jurisdiction. Here, probate was usually handled by other church officials or, in a handful of cases, lords of manors. There were no peculiars in this part of North Staffordshire, nor were there any significant changes in the jurisdiction of the Consistory Court over an extended period. Both of these factors significantly simplify the search for pre-1858 wills. Humphery-Smith (2003) maps parishes to probate jurisdictions for all pre-1974 counties (see Maps section below, p. 19).

Lichfield Record Office, which held most LCC records, has now closed and the records have been transferred to the SSA’s main facility at Stafford. Survival of original consistory wills is good after 1600, although few inventories survive after around 1750. The LCC holdings are summarized in the Handlist to the Diocesan Probate and Church Commissioners’ Records (2nd edn, 1978). There is a good nineteenth-century calendar to LCC Wills and Administrations, 1516–1857, and a separate index to records of peculiars. Printed versions of these indexes to 1652 (published by the British Record Society) are less accurate.

In a major boon for Staffordshire researchers, these indexes as well as digitized images of the original wills and administrations proved in the LCC are available as part of the Staffordshire Collection on Findmypast. Elsewhere online, partial indexes to LCC probates are available through Staffordshire Name Indexes for the period 1630–1780 (www.staffsnameindexes.org.uk) and Ancestry for the period 1516– 1652.

In general, where someone held property or goods within one diocese only, the will was proved, or administration granted, in that court. If held in two dioceses, then the grant was made in higher courts at either Canterbury or York. Indexes to Prerogative Court of Canterbury (PCC) wills can be searched free of charge on the TNA website (with copy wills available to purchase), while Findmypast has indexes to wills proved in the Prerogative Court of York (PCY), 1688–1858.

The SSA is the custodian of a wide range of photographic collections. Highlights from these collections are showcased at the Staffordshire Past Track website, which provides access to photographs, images, maps and film and audio clips through easy-to-use search tools (www. staffspasttrack.org.uk). The site covers more than 30,000 resources in total, some of which are available to purchase and download. The SSA’s full photographic collection can be searched using the Gateway to the Past search engine (www.archives.staffordshire. gov.uk, specify ‘photographs’ under DocType).

Some of the images on Staffordshire Past Track are derived from the collections of private photographers. One such was J.A. Lovatt, who lived in Normacot and was a member of the North Staffordshire Field Club in the 1920s. His collection of photographs of Longton and area is held at the STCA [SD 1752]. Another Longton-based photographer with images on Past Track is William Blake. Born in the United States in 1874, Blake emigrated with his family to Britain and settled in Longton, where he set up a stationer’s shop on Stafford Street (now the Strand). He was a key member of the North Staffordshire Field Club, acting as librarian for the society’s photograph collection (which is now housed at the Staffordshire County Museum). He died in 1957.

Wharf Street, Longton, c. 1905 photographed by William Blake. (Staffordshire Past Track)

Other notable image collections held at the STCA are:

•The Beard Collection: Photographs of Burslem, Hanley and Tunstall taken by Derek Beard, 1959–c. 1962 [STCA: SD 1635, currently uncatalogued].

•The J.R. Hollick Collection: Approximately fifty albums and loose photographs, mainly relating to railways in North Staffordshire during the 1920s and 1930s (not catalogued).

•The Bentley Slide Collection: A series of over 6,000 colour slides taken by Bert Bentley in the early 1960s under commission from Stoke-on-Trent Libraries [SD 1480].

•The Watson Collection: Photograph albums, photographs, film recordings and ephemera recording the city’s industrial and social heritage compiled and donated by Stoke-on-Trent resident Mark Watson [SD 1537].

•The Morgan Photographic Collection: A large collection of late twentieth-century photographs donated by Jim Morgan [SD 1655].

The Warrillow Collection at Keele University comprises over 1,800 photographs of the Potteries area dating from the 1870s to the 1970s (www.keele.ac.uk/library/specarc/collections/). The majority were taken by Ernest James Warrillow, a press photographer with the Sentinel newspaper from 1927–74. He graphically recorded the changing landscape and people of the Potteries and collected old photographs and engravings. The STCA has a printed catalogue. Keele is also home to the William Jack Collection, comprising around 2,000 photographs of North Staffordshire’s industrial heritage taken by Chatterley Whitfield Colliery employee William Jack during the 1920s and 1930s.

Pastscape (www.pastscape.org.uk) is a portal to information on archaeological and architectural heritage across England, run by Historic England (formerly English Heritage). It has descriptions, and in some cases pictures, of sites and buildings referenced within historical sources, including over 5,000 in Staffordshire. A related service, ViewFinder, has historic photographs from the Historic England Archive (http://viewfinder.english-heritage.org.uk), while the full catalogue has over 1 million entries describing photographs, plans and drawings of buildings and historic sites (http://archive.historicengland.org.uk). Information on all buildings that have received listed status is available at www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk.

Staffordshire Views is a unique series of illustrations of churches, public buildings, country houses and landscapes from all over Staffordshire, dating mainly from the 1830s and 1840s (www. views.staffspasttrack.org.uk). Staffordshire Prints offers artwork from local museums to purchase in various forms, including fine-art posters and prints (www.magnoliabox.com/collections/staffordshireprints).

The photo-sharing site Flickr has many members and groups devoted to photography around and relating to the Potteries, both contemporary and historic. One of the largest is www.flickr.com/ groups/stoke-on-trent. The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery and the Gladstone Museum each have social media channels where they share images from their collections (www.stokemuseums.org.uk). Facebook, Twitter and Instagram all have photo-sharing communities.

There are many Stoke-on-Trent galleries within the Geograph database, which aims to collect geographically representative photographs and information for every square kilometre of Great Britain and Ireland (www.geograph.org.uk).

Potteries.org has numerous photographs, both old and new, relating to the area and its heritage culled from various sources (www.thepotteries.org/photos.htm). The work of recent and contemporary photo historians is presented, alongside aerial photos of the city, watercolours, paintings and old postcards. The site has more than 100 drawings of buildings in the Potteries by artist Neville Malkin which originally appeared in the Evening Sentinel during the 1970s (http://thepotteries.org/tour/index.htm).

Several books have been published presenting the Potteries and surrounding area through old photographs and postcards (see Publishers section in Appendix 2).

The Media Archive for Central England preserves the ‘moving image heritage’ for both the East and West Midlands (www.macearchive. org). Its online catalogue contains 50,000 titles for Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent. Many of these are part of the Staffordshire Film Archive, a specialist archive of original films for the county which was founded and developed by Ray Johnson MBE (www.filmarchive.org. uk). The Media Archive for Central England offers a range of high-quality DVDs and films for sale and/or download.

The West Midlands History portal regularly produces short films, which are free to view online, uncovering the stories of the people and events that shaped the region (www.historywm.com). A collection of archive films on Staffordshire is available on the British Film Institute website (http://player.bfi.org.uk). Stoke-on-Trent Past in Pictures is a DVD from commercial publisher UK History Store (www.ukhistory store.com) containing recordings made between the 1930s and the 1970s, many of which have not been published before.

Maps are an essential resource for family historians, helping to provide a more detailed understanding of where and how our ancestors lived.

Before the advent of the Ordnance Survey in the nineteenth century, mapping relied on a series of county maps produced privately by individuals or small groups of surveyors with wealthy patrons. In some cases these would be bound into volumes of county atlases. The earliest map of Staffordshire dates from 1577 and was produced by the mapmaker Christopher Saxton. It is surprisingly accurate and detailed for its time, showing settlements and geographical features. In common with other early county maps, however, it shows no roads. Other early maps of the county include Smith’s map of 1599 and Kip’s map of 1607.

The famous John Speed mapped Staffordshire in 1610, again including main features but omitting the roads. Some of these early maps were reproduced at a small scale for inclusion in ‘pocket atlases’, while others started to feature town plans with key buildings and street names. John Bill’s miniature version of 1626 was the first to show degrees of latitude and longitude. Robert Plot’s map of 1682 was highly detailed and became a benchmark for others to follow.

During the eighteenth century county maps improved in accuracy, with the addition of roads and ways of differentiating between main routes and minor lanes. William Yates undertook a scientific survey to produce the first large-scale map of the county in 1775; a second smaller edition followed in 1798. The first half of the nineteenth century saw further refinements and in 1820 Christopher Greenwood produced a large-scale, 1in-to-the-mile map based on a detailed survey. By this time, however, the Ordnance Survey had begun its work and the age of privately surveyed county maps was drawing to a close. The first edition 1in Ordnance Survey sheet of the Potteries was published in 1837, from survey work undertaken between 1831 and 1837. Second and third editions were released in stages around 1881 and 1908, respectively.

Detail from Yates’s Map of 1798. (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)

The SSA’s map collection covers many types and periods. The majority of original printed county maps are held at the William Salt Library, while the SRO holds copies of Greenwood’s map of 1820, reprints of earlier county maps and various printed and administrative county maps dating from the twentieth century. The collection can be searched using the Gateway to the Past search engine (www.archives. staffordshire.gov.uk, specify ‘maps and plans’ under DocType). The Staffordshire Past Track portal allows map-based searches across a variety of themes relating to the county’s history (www.search.staffs pasttrack.org.uk/mapexplorer.aspx?).

Enclosure – the process by which land farmed in common was divided into enclosed fields – required the areas affected to be mapped in great detail (see Chapter 8). From the mid-eighteenth century, enclosure by Act of Parliament became standard practice and it is from this period that much of the documentation survives. The SRO holds documents relating to enclosure, mostly for the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which may include surveys, maps and plans. SSA Guide to Sources No. 5: Staffordshire Enclosure Acts, Awards & Maps has a detailed list of holdings.

Further change to agricultural communities came with the Tithe Commutation Act of 1836, which abolished the in-kind payment of tithes and substituted rent charges. This required accurate maps of the country measuring acreage and recording the state of cultivation. For some places the tithe maps were the first detailed maps, although the results were of variable quality. Together with the accompanying apportionment schedule, the tithe maps show who owned and who rented land. Most of the maps for North Staffordshire were produced between 1839 and 1852. Copies are likely to be found at TNA, the SRO and the WSL (explained further in Chapter 8). SSA Guide to Sources No. 3: Tithe Maps and Awards provides a detailed listing.

Potteries.org has a large collection of maps from across the area, including local detail from Yates’s map of 1775 (www.thepotteries.org/ maps/index.htm). Early Ordnance Survey maps and factory and estate plans are also well represented.

The City Surveyor’s Map Collection [SA/CS] at the STCA contains numerous types of maps made by the Stoke-on-Trent City Surveyor’s Department, mainly from the period 1920–50. Aspects covered include: bus and tramway routes, new housing schemes, utilities and maps of bomb damage and air raid precautions from the Second World War. There is a catalogue in the STCA Search Room.

Because the Six Towns had grown up independently many street names had been duplicated, which led to confusion as people started to move more freely around the city. For example, there were seven Albert Streets, eleven Church Streets and twelve High Streets. In the early 1950s a large number of streets were renamed. The STCA has a list of changed street names that was originally compiled by the City Council in 1955 and reprinted in 2001 by the North Staffordshire Branch of the BMSGH (now out of print). The listing is also available on Potteries.org, cross-referenced by old name, new name and district, together with more recent street listings (www.thepotteries.org/ streets/index.htm).

When researching in a new area it is essential to know what parish registers are available and which are the neighbouring parishes. The definitive source for this is The Phillimore Atlas and Index of Parish Registers (Humphery-Smith, 2003). It lists the availability of registers for a given parish, and shows the neighbouring parishes as well as the relevant probate jurisdiction for wills and administrations. The parish maps from the Phillimore Atlas, produced by the Institute of Heraldic and Genealogical Studies, are available on Ancestry as Great Britain, Atlas and Index of Parish Registers (https://search.ancestry. co.uk/search/db.aspx?dbid=8830).

FamilySearch has a facility to compile maps made up of various layers, such as parishes and PLUs, to see how they relate to each other; this is very useful in an urban area such as Stoke-on-Trent (http://maps.familysearch.org).

The excellent National Library of Scotland website has a huge selection of Ordnance Survey and other maps covering the whole of the British Isles (https://maps.nls.uk). Other rich sites for historical maps are: Genmaps (http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ genmaps/); MAPCO (http://mapco.net); Old Maps Online (www.old mapsonline.org); and Vision of Britain (www.visionofbritain.org.uk).

An Historical Atlas of Staffordshire (Phillips and Phillips, 2011) provides an academic perspective on Staffordshire’s historical geography.

Provincial newspapers began to become established in England in the early eighteenth century. Before this news reached the English countryside through manuscript newsletters, printed newsbooks and newspapers produced in London. Politicians saw the growth of cheap newspapers as dangerous, fearing they would radicalize the lower classes, leading to social unrest and even revolution. Taxes were levied on paper and advertisements as well as a stamp duty on newspapers in an effort to restrict their growth. As the tax was per sheet of paper, the pages grew larger and larger and the print became smaller and smaller to accommodate more news. Many newspapers continued as so-called ‘broadsheets’ until recent times.

Newspapers are a valuable but often underused resource for the family historian. They can be a gateway to a wealth of information, some of which is not available elsewhere; or they may lead on to other sources. The types of information to be found include: obituaries, birth, marriage and death announcements, bankruptcies and dissolution of partnerships, name changes, court cases, school and university examination results, military appointments and promotions, and gallantry citations and awards.

Masthead of the Staffordshire Sentinel, 19 May 1873.

Court cases and inquests are a staple of all local papers. Usually a reporter would be sent along and took down, verbatim, what was said. Witnesses, such as family members, would be questioned, perhaps revealing key information, such as marital infidelity or a separation. Obituaries also give a lot of information: as well as a summary of the deceased’s life, they may mention family relationships and provide a list of people who attended the funeral. As the areas covered by newspapers often overlapped, and some of the content was syndicated between titles, an event may not necessarily be reported (or have survived) in the nearest local newspaper.

The main newspaper for the Potteries was, and remains, the Staffordshire Sentinel, later the Evening Sentinel and now the Sentinel (www.stokesentinel.co.uk). Although not the first to be published in the area (see p. 26), it has outlived all others and has come to be regarded as a Potteries institution.

The STCA has a substantial collection of newspapers from the Potteries and the wider county available on microfilm (see Table 1.2 below). There are long runs of the Staffordshire Sentinel from 1854 through to 1985, and the Staffordshire Advertiser, a county wide newspaper, from 1795–1973, as well as two bound volumes of indexes to birth, marriage and death announcements published in that newspaper between 1795 and 1840 (produced by the Staffordshire Record Society). A separate typescript index covers items from the Staffordshire Advertiser, 1870–84 for the parish of Audley and surrounding villages. The WSL also holds a complete run of the Staffordshire Advertiser from 1795–1973.

Newcastle-under-Lyme Library has an almost complete run of the Sentinel, in all its manifestations, from 1854 on microfilm, plus various others including two local titles: Newcastle Guardian (1900–9) and Newcastle Times (1938–73).

Table 1.2: Newspaper Series at Stoke-on-Trent City Archives

| Newspaper | Years Held |

| Miner & Workman’s Examiner | 1874–8 |

| North Staffordshire Advertiser | 2000–3 |

| Potteries Examiner | 1871–81 |

| Potteries Examiner & Workman’s Advocate | 1843–7 |

| Pottery Gazette | 1879–1914 |

| Staffordshire Advertiser | 1795–1973 |

| Staffordshire County Herald | Occasional from |

| 1831/2 | |

| Staffordshire Knot | 1882–91 |

| Staffordshire Mercury | 1830–45 |

| Staffordshire Sentinel | 1854–2009 |

| Stoke-on-Trent City Times | 1935–69 |

Staffordshire is well represented in the British Newspaper Archive, an ambitious project to digitize British nineteenth-century newspapers being undertaken as a joint venture between the British Library and DC Thomson Family History (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk). Titles relating wholly or partially to North Staffordshire include: Leek Post & Times/Cheadle News & Times/Moorland Advertiser, Staffordshire Advertiser, Staffordshire Gazette and County Standard, and Staffordshire Sentinel (including some under the original name of Staffordshire Sentinel and Commercial & General Advertiser). Ancestry has a very limited run (just four years) of the Staffordshire Sentinel. Print, microfilm and digitized newspapers can also be viewed at the Newsroom, the British Library’s specialized reading room at St Pancras, London (www.bl.uk /subjects/news-media).

National newspapers can be an important source for legal and family announcements (especially for the upper classes). The London Gazette, published since the mid-1600s, is freely available online (www.the gazette.co.uk). National and some local titles are accessible through subscription services, such as the Gale Newspaper Database and The Times Digital Archive (1785–1985); many libraries offer free access either within library buildings or from home for library members.

SPREADING THE NEWS: NEWSPAPERS IN NORTH STAFFORDSHIRE

The first newspaper known to have been printed in North Staffordshire was the Pottery Gazette and Newcastle-under-Lyme Advertiser, which made its appearance in January 1809. Financed by pottery owners looking to advertise their wares, it was thought by some to be ‘decidedly Tory and aristocratical’ in tone and lasted a little over a year. Another Pottery Gazette was established in 1822 and lasted for six years. Meanwhile, Thomas Allbut had started the Pottery Mercury – later known as the Staffordshire Mercury – as a moderate Liberal newspaper in 1824 and this continued for around twenty years. Other titles that appeared around this time were the Potteries Examiner (published from 1823–46); the North Staffordshire Independent (early 1850s); and the Staffordshire Potteries Telegraph (dates unknown). Increasingly, such papers began to promote the interests of pottery workers, in some cases from a strong religious standpoint.

In 1853 a group of Liberal reformers decided to launch a new weekly paper. One of their objects was to campaign for the incorporation of Hanley to free it from the outmoded, and allegedly corrupt, Improvement Commissioners and other bodies who were running the town’s affairs at that time. Among the newspaper’s early supporters were: Edward Challinor, a local solicitor; Edmund Oswald, a potters’ commission agent; and a commercial traveller named Samuel Taylor who was a pioneer of the ‘penny readings’, a primitive form of adult education in the area. All of these appear to have put money into the venture and secured the support of John Keates, a local printer.

The Staffordshire Sentinel and Commercial and General Advertiser was first published on 7 January 1854 from offices in Cheapside, Hanley. The publisher was Hugh Roberts, a former printer, and the editor was Thomas Phillips, a radical campaigner and former bookseller. By 1872 circulation of the Sentinel had increased to 5,000 copies weekly with 90 agents covering the whole of North Staffordshire and part of Cheshire. The following year, 1873, the paper became a daily, published from Monday to Friday, with a separate weekly edition on Saturdays.

Under its then editor, Thomas Andrews Potter, and his successors the Sentinel became a strong campaigning force that did not shy away from political controversy. It was a deep influence on Arnold Bennett, who made a newspaper called ‘The Signal’ a centrepiece of several of his novels. During the twentieth century the Sentinel shed its partisanship and extended its reporting horizons, both thematically and geographically. In March 2014, the Sentinel was awarded the Freedom of Stoke-on-Trent. It is now part of the Trinity Mirror Group.

As a centre dependent on the production and sale of manufactured goods, trade directories were an essential means for North Staffordshire firms to publicize their wares. In the early years Stoke-on-Trent tended to be covered as part of county directories for Staffordshire (and sometimes neighbouring counties as well); later on, as the district’s importance grew, dedicated directories were produced. Most directories provide a history of the locality and descriptions of amenities such as schools, workhouses and churches. As well as businesses, some directories list every resident or building and/or the members of local councils and other administrative bodies.

The STCA has a collection of trade and commercial directories covering Stoke-on-Trent and Staffordshire, 1783–1940. These are produced by well-known publishers such as Kelly, Pigot, the Post Office, Slater and White and are available in various formats. City of Stoke-on-Trent Directory with Newcastle-under-Lyme, published in 1963 (Barrett’s Publications), gives a more recent picture of industry in the city, just at the point at which it was starting to decline. Also of note is Leek Trade Bills c. 1830–1930 – a source collection on trade and business in Leek compiled from letterheads, advertisements and directories (Poole, 2003–7).

The SRO and the WSL have their own collections. The excellent Potteries, Newcastle and District Directory, published by the Staffordshire Sentinel Ltd in 1907 and 1912, lists, with a few exceptions, every householder in the district including the rural areas [WSL: PN4246]. Keele University Library (which is open to the general public) and Newcastle-under-Lyme Library each have selections. Potteries.org has scans and transcriptions of various trade directories, including a 1955 publication by the North Staffordshire Chamber of Commerce.

Historical Directories of England and Wales, part of the University of Leicester’s Special Collections Online, has many digitized trade directories for Staffordshire and other Midlands counties from the 1760s to the 1910s, which are free to download (accessible via http://special collections.le.ac.uk). Midlands Historical Data is a commercial publisher offering digitized copies of trade and commercial directories to purchase on CD-ROM; subscription and pay-as-you-go options are also available (www.midlandshistoricaldata.org). The Midland Ancestors Reference Library, the Society of Genealogists and TNA all have good runs of Midlands directories.

The introduction of the telephone brought the need for a new type of listing. Ancestry has a good collection of historical telephone directories from across the UK under ‘British Phone Books, 1880–1984’. Forebears who worked in the Post Office are likely to be found in the British Postal Service Appointment Books, 1737–1969, and also on Ancestry.

Like other areas, North Staffordshire has its own collection of distinctive surnames, many of them unique to the district. Local historian Edgar Tooth has made an exhaustive study of the origins and distribution of such names. This scholarly work documents in extensive detail the origins of a multitude of surnames native to North Staffordshire and is required reading for any researcher tracing a distinctive name. The results were published in a four-volume series issued between 2000 and 2010 by Churnet Valley Books. Potential origins considered are local placenames and landscape features (Tooth, 2000); occupations, trade, rank and office (Tooth, 2002); nicknames (Tooth, 2004); and personal and pet names (Tooth, 2010).

Obituaries in newspapers and periodicals can provide important biographical details on our ancestors that might not be found elsewhere. As well as mainstream publications, church and parish magazines can be useful in this respect (see Chapter 4).

Potteries.org has mini-biographies of leading figures in business, civic life and other fields, as well as an index to people mentioned elsewhere in this huge website (www.thepotteries.org/biographies). Contemporary Biographies by Cameron Pike, published in 1907, is a series of pen portraits of leading figures in ‘Staffordshire and Shropshire at the opening of the twentieth century’ (all men, of course!). People of the Potteries: A Dictionary of Local Biography by Denis Stuart (University of Keele, 1985) is a similar but much later listing.

Anonymous, The Sentinel Story: 1873–1973 (James Heap Ltd, 1973)

Humphery-Smith, Cecil R., The Phillimore Atlas & Index of Parish Registers (3rd edn, Phillimore, 2003)

Phillips, A.D.M. and C.B. Phillips, An Historical Atlas of Staffordshire (Manchester University Press, 2011)

Poole, Ray, Leek Trade Bills c.1830–1930, 3 vols (Churnet Valley Books, 2003–7)

Raymond, Stuart A., The Wills of Our Ancestors: A Guide for Family & Local Historians (Pen & Sword Family History, 2012)

Tooth, Edgar, Distinctive Surnames of North Staffordshire: Vol. One: Surnames Derived from Local Placenames and Landscape Features (Churnet Valley Books, 2000); Vol. Two: Surnames Derived from Occupations, Trade, Rank and Office (Churnet Valley Books, 2002); Vol. Three: Surnames Derived from Nicknames (Churnet Valley Books, 2004); Vol. Four: Surnames Derived from Personal and Pet Names (Churnet Valley Books, 2010)