The Domesday Survey of 1086 contains little evidence for the settlements that form modern-day Stoke-on-Trent. Stoke is mentioned as part of the royal manor of ‘Pinchetel’ (Penkhull), over 1,000 acres of arable land that covered much of present-day Newcastle-under-Lyme, Hanley, Shelton, Stoke and Boothen. It is likely that Tunstall is accounted for within the manors of Thursfield and/or Chell. Fenton-Vivian or Little Fenton was at that time a separate manor to Fenton Culvert or Great Fenton, which appears to have been attached to Buckenhall Eaves (hence ‘Bucknall’). Longton is believed to have been part of the manor of Wolstanton. Only Burslem (‘Barcardselim’) is recorded as a separate manor at that time, held by Robert of Stafford. It was assessed for a third of a hide and was worth 10s. a year (meaning it was very poor).

Domesday Book shows that Staffordshire as a whole was sparsely populated compared with other counties, with extensive woodlands and largely uninhabited uplands. The Normans had ravaged the area in the effort to exert their authority after the Conquest. Rebellions were put down mercilessly, motte and bailey castles were built at Chester, Stafford, Dudley and Tutbury, and large areas of Staffordshire including Cannock Chase were designated for royal hunting. Hemmed in by the landscape and oppressed by a tyrannical regime, the populace had to rely on subsistence agriculture.

Penkhull is probably the earliest inhabited place within the Potteries district, its hill-top position having attracted, in turn, the Celts, Romans and Anglo-Saxons. Its situation afforded easy access to wooded hunting grounds, clear views over the surrounding countryside and proximity to streams in the Lyme Valley to the west, and the Trent Valley to the east. But in the twelfth century the Normans built a ‘new castle’ to the west of Penkhull and from this point its influence began to decline.

A market town quickly grew up within sight of this castle and by the year 1173, the Borough of Newcastle-under-Lyme (‘New Castle under the Elm Trees’) had been established. By the mid-1230s many of the manors in the area had become closely associated with Newcastle. In the centuries that followed, Newcastle-under-Lyme grew to be the largest centre of population and leading market town. It would dominate the history and economy of North Staffordshire for the next 600 years, until the arrival of the Potteries in the eighteenth century.

Apart from the burghers of Newcastle, the other force in North Staffordshire in the medieval period was the Church. The Cistercians settled in the moorlands regions, establishing houses at Croxden in 1179, Dieulacres (near Leek) in 1214 and at Hulton in 1219. An Augustinian priory was founded at Trentham in 1150. These religious houses wielded considerable power. They operated large estates, managed through dependent farms and granges, and were not averse to clearing existing villages and hamlets to make way for new farms. Hulton and Trentham, in particular, depended on wool for a large part of their income and on occasion disputes broke out between them over pasture rights.

The medieval period saw a boom in church building and restoration. St Peter ad Vincula, Stoke, St John the Baptist, Burslem, St Giles, Newcastle, and St Edward the Confessor, Leek, were all either established or expanded during this period, as well as many others.

What were to become staple industries were beginning to develop. Coal was being mined at Tunstall by 1282, Shelton by 1297, Norton-inthe-Moors by 1316 and Keele by 1333. Drift mining or shallow excavation with bell pits would have been used. Iron ore was being mined in the Tunstall area by the thirteenth century and spread to Longton, Knutton, Chesterton and Talke. Newcastle’s Ironmarket suggests that it was a centre for the buying and selling of the resulting ore. At that time the ore would have been smelted in small furnaces that served the local market.

Until relatively recently archaeological evidence for pottery-making in the region during this period was scant. But in 2000 large quantities of late medieval pottery were discovered during building work at the Burslem School of Art, where William Moorcroft and many other famous ceramic artists learned their trade. The trove included large pottery bowls and jugs from the 1400s in styles known as Cistercian ware (a brown glazed earthenware made from clay rich in irons) and white ware (another form of earthenware made from white-firing clays with low levels of iron). Other evidence comes from Sneyd Green, where excavations have revealed a series of small-scale kilns. Overall, however, the industry appears to have still been a domestic sideline at this time.

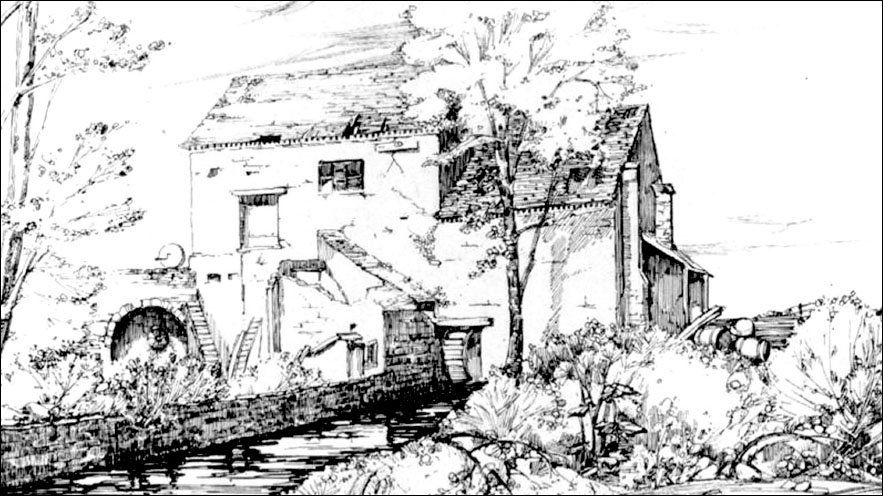

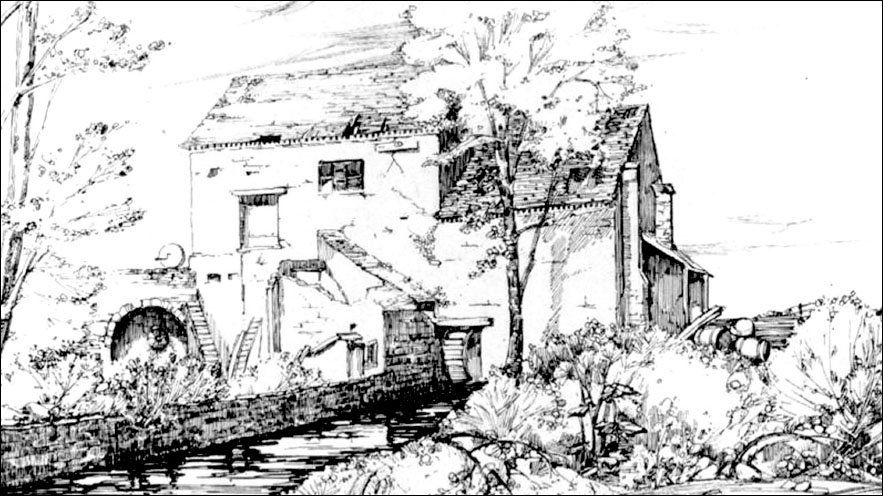

Abbey Hulton mill, from ‘Ten Generations of a Potting Family’ by William Adams. (Courtesy of thepotteries.org)

The Manorial Documents Register, administered by The National Archives, is a centralized index to manorial records for England and Wales. It provides brief descriptions of documents and details of their locations in both public and private hands. The index is now largely computerized (including Staffordshire) and forms part of the TNA Discovery Catalogue (http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ manor-search).

Manorial records include court rolls, surveys, maps, terriers and other documents relating to the boundaries, franchises, wastes, customs or courts of a manor. Although manorial records do not record births, marriages or deaths as such, they may contain considerable information about individuals, including approximate dates of death. The key records here are those relating to changes in tenancy on the death of a tenant: presentments and admittances. Other useful records are: lists of jury members and manorial officials; presentments and orders giving the names of those who offended against local byelaws and committed minor crimes; and civil pleas brought against neighbours or others in the community in cases of debt or trespass.

Survival is patchy and as the ownership of manors changed frequently and did not necessarily remain within the local area, manorial documents can be spread far and wide. SSA Guide No. 7: Manorial Records is a guide to its holdings for manors in both Staffordshire and other counties. North Staffordshire manors with entries in the list from before 1500 include: Audley, Betley, Biddulph, Bucknall, Leek, Norton-in-the-Moors, Trentham and Whitmore. Use the Manorial Documents Register to identify potential holdings elsewhere.

The publications of the Staffordshire Record Society are a rich resource on medieval Staffordshire and its history (www.s-h-c.org.uk). The Society has published many medieval manuscripts and documents from the county in its journal Collections for a History of Staffordshire (referred to below as simply Collections). Key record series which are likely to include names from the period include pipe rolls, plea rolls and feet of fines, episcopal, cathedral and monastic records, lay subsidies and early Quarter Sessions records. These tend to be county-wide without specific reference to North Staffordshire. A key source for general history is its annotated version of Walter Chetwynd’s History of Pirehill Hundred With Notes by Frederick Perrot Parker (in two parts: New Series, Vol. XII (1909) and Third Series (1914)). It includes the pedigrees of notable Staffordshire families. Some SRS volumes have been digitized and are available via the Internet Archive (www.archive.org).

The Staffordshire Historical Collections on British History Online have various plea rolls and other medieval documents (www.british-history.ac.uk/staffs-hist-collection).

Durie (2013) and Westcott (2014) provide further insights into interpreting and understanding early documents. The Medieval Genealogy website contains links to numerous sources, including public records, charters, manorial records, early church and probate records, funeral monuments and heraldry (www.medievalgenealogy.org.uk). The heraldry of Staffordshire has been discussed in various articles in the Midland Ancestor, the journal of Midland Ancestors.

At the beginning of the sixteenth century the religious houses continued to exert influence, even though the numbers of brethren were in steep decline. When Trentham Priory was dissolved in 1536 it possessed huge tracts of land across North Staffordshire, yet had only eight priors in residence. They were each granted annuities and either took up positions as rectors locally or moved away.

Farming prospered during this period. It was largely pastoral, with livestock being moved between upland and lowland pastures during the year and preference given to cattle over sheep. More land was brought under cultivation by clearing woodland and the use of former ‘waste’. The enclosure of open fields began: Tunstall was enclosed by 1614 and visitors in the late seventeenth century commented on the quantity of enclosures around the county compared with elsewhere. Yeoman farmers such as the Fords at Ford Green Hall, Smallthorne, showed off their new-found wealth by building large timber-framed houses (http://fordgreenhall.org.uk).

Although Staffordshire as a whole featured prominently in the English Civil Wars, hostilities were concentrated in the south of the county, in areas such as Lichfield, Tamworth, Cannock and Stafford. North Staffordshire escaped the worst excesses, though the area was traversed frequently by both the Royalist and Parliamentary armies en route to engagements elsewhere. At the outbreak of the conflict in 1642 the Staffordshire Moorlands was controlled for Parliament by Sir John Bowyer of Knypersley and there was a Royalist garrison at Biddulph. At Keele Hall, the Sneyds opted for the king and garrisoned their property, but it soon fell to Parliament. The nearest thing to a battle was a skirmish at Biddulph Old Hall in 1644. After winning over Cheshire, the Parliamentary forces laid siege to the hall where several Catholic families had sought refuge. Heavy artillery was used against the contingent of 150 troops and the occupants were left with no alternative but to surrender. The hall was subsequently plundered by the local population and remains a ruin today.

Ford Green Hall. (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)

By this time the farmer-potters were beginning to upscale their operations. There are records of pottery being made in Penkhull by about 1600, as well as dish-making at Tunstall. In 1635 three men from Tunstall appeared before the manor court accused of digging holes in the road to obtain clay. In Burslem, a trade in the manufacture of butterpots, used in making butter, developed; these were large cylindrical pots made of unglazed material. Writing in his Natural History of Staffordshire in 1686, Robert Plot commented on the prevalence of pottery in the area and described Burslem as the mother town. Plot observed that the potters lived in small cottages in their own area of enclosed land, with bottle-shaped kilns adjoining: ‘The greatest pottery they have in this county is carried on at Burslem, . . . for making their several sorts of pots they have as many different sorts of clay, which they dig round about the towne . . . the best being found nearest the coale’. Around this time the practice of glazing with salt was developed as an alternative to the lead glaze used previously. According to some accounts, it was introduced by two Dutch potters called the Elers brothers in their potwork at Bradwell; others attribute it to an accidental discovery in a small pottery at Bagnall. Saggars – fireclay boxes used to hold the wares during firing – were also introduced around this period (see Chapter 2).

New equipment; novel approaches to glazing and preparing the clay; innovations in firing within the oven; and markets for the resulting wares: little by little the potter’s art was being assembled, ready to be kick-started in the century that followed.

In 1641–2, all males over the age of 18 were required to swear an oath of Protestant loyalty, as part of efforts to count and tax Roman Catholics. Each parish compiled protestation oath returns that were submitted to Parliament, effectively making this a census of all adult males. Regrettably, few records survive. In Staffordshire, the south of the county – Offlow hundred – is well covered but in the north only returns for Newcastle-under-Lyme and Stow (both in Pirehill hundred) survive. There are no returns at all for Totmonslow hundred (the north-east). These records are held at the House of Lords Record Office and available online (http://digitalarchive.parliament.uk using references HL/PO/JO/10/1/105/42 and 43 respectively for the two Pirehill series). A similar oath list from 1722, following the Jacobite Rebellion is within the Staffordshire Quarter Sessions [Q/RRo].

Following the Restoration, other taxes were introduced in order to rebuild the country’s shattered economy. The hearth tax was a graduated tax based on the number of fireplaces within each household. Introduced in 1662 by Charles II, the hearth tax was collected twice a year, at Michaelmas and Lady Day. A person with only one hearth was relatively poor, whereas somebody with six or more could be considered very affluent. Persons with houses worth less than 20s. per annum were exempt, as were those in receipt of poor relief, otherwise 2s. per hearth was payable. This unpopular legislation was repealed in 1689. The SRS has published the Staffordshire hearth tax for 1666: this was released in stages between 1921 and 1927 and is denoted as part of Collections, Third Series. Hearth Tax Online is an academic project providing data and analysis of the hearth tax records (www.hearthtax.org.uk and http://hearthtax. wordpress.com).

Engraving of Staffordshire historian Walter Chetwynd by Robert White. (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)

A particularly important source for this period is a list of Stoke-upon-Trent residents drawn up in 1701. Pre-dating the modern census by more than 100 years, such lists were compiled occasionally for a variety of reasons. The Stoke list is dated 2 June 1701 and is written on the first forty pages of a seventy-two-page quarto paper booklet. The listing begins with the date and a brief description of the area included and the format of the entries. It is described as: ‘A collection of the names of every particular and individual person in the parish of Stoke-upon-Trent, in the County of Stafford, as they are now residing within their respective Liberties and Families within the said parish; together with the age of every such person, as near as can conveniently be known . . .’. The whole list has been published by the SRS as The Stoke upon Trent Parish Listing, 1701 (Collections, Fourth Series, Vol. XVI).

The SRS has published a long series of rolls from the Staffordshire Quarter Sessions, 1581 through to 1608, transcribed by Sambrooke Arthur Higgins Burne. These appeared in various issues of Collections, Third Series between 1929 and 1949. Two particularly name-rich sources transcribed from lists at Staffordshire Record Office are: The Gentry of Staffordshire 1662–3 (Fourth Series, Vol. II) with additions (Fourth Series, Vol. XIII); and List of Staffordshire Recusants 1657 (Fourth Series, Vol. II).

Other records from this period published by the SRS include: Muster Rolls for 1539: Hundreds of Cuttleston and Pyrehill (New Series, Vol. V); Hundreds of Seisdon and Totsmonlow (New Series, Vol. VI, Part 1); Transcripts of Staffordshire Suits in the Court of Star Chamber during the reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII (various volumes, 1909–12); A Subsidy Roll of 1640 (Pirehill Hundred) (Third Series, 1941); Militia Roll For Pirehill Hundred c.1685 (Third Series, 1941); Notes on Staffordshire Visitation Families by William Fowler Carter (Third Series, 1910); and numerous family histories, for example, The Mainwarings of Whitmore and Biddulph (Third Series, 1933).

The Manorial Documents Register has many documents from this period for manors across North Staffordshire; for example, surveys and rentals from the early 1600s (see above). Similar records can sometimes be found in family and personal papers, such as those for the manor of Newcastle-under-Lyme (at Penkhull) in the Adams Collection [SD1256/EMT7/801A]. The SRO has records of Freemen’s Admissions for Newcastle, 1620–1906.

The heralds’ visitations were enquiries by the College of Arms into those that claimed the right to bear arms (armigers) by investigating their pedigrees. Between 1530 and 1686, heralds travelled the country producing a vast number of pedigrees and family trees – many of questionable accuracy – as well as notes and other comments. The visitations for Staffordshire (1583, 1614, 1663–4) have been published by the Harleian Society and others; facsimiles are readily available online (see www.medievalgenealogy.org.uk/sources/visitations. shtml).

In the absence of both a local aristocracy and large mercantile centres, the economy of North Staffordshire began to be dominated by a provincial, land-owning class.

In 1540 William Sneyd purchased a large estate at Keele from the Crown; it had belonged to the Knights Hospitallers before the Dissolution. The Sneyds were related to the powerful Audley family of Cheshire and an ancestor had fought against the French at Poitiers in 1356. They became successful drapers and merchants in Chester and were even more successful at marrying wealthy heiresses. Little by little from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries the family grew in stature.

Western aspect of Keele Hall from the gardens. (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)

William Sneyd’s son Ralph built the first Keele Hall in 1580. But having aligned with the wrong side during the Civil War, the family fell into decline. Its fortunes were revived when Lieutenant Colonel Walter Sneyd became a Member of Parliament from 1784 to 1790. He commanded the Staffordshire Militia, which served for thirteen years as a bodyguard to George III at Windsor (see Chapter 9), a position from which he managed to accrue many advantages. His successor, Ralph Sneyd, invested in coal mines at Silverdale and elsewhere that further increased the family’s wealth. This he ploughed into managing and improving the estate, eventually rebuilding Keele Hall in 1860. In the early twentieth century, the Sneyd family’s association with Keele gradually dwindled in the face of an expensive social life, economic failure and indifferent absentee ownership. The estate remained in the family until 1949, when it was acquired as the home of the newly created University College of North Staffordshire, later to become the University of Keele.

Even more powerful than the Sneyds was the Leveson-Gower family, Dukes of Sutherland. The Leveson family originated in medieval Willenhall, near Wolverhampton, as small-scale sheep farmers. Using the profits from the sale of wool, they expanded their estates in south Staffordshire and members of the family established themselves in the London wool trade. Like the Sneyds, the Levesons were quick to see the economic opportunities brought by the Reformation. Having already bought Lilleshall Abbey in Shropshire, James Leveson purchased Trentham Priory, Stone Priory and other Church estates. The family continued to live at Lilleshall until settling at Trentham in 1630.

In the late seventeenth century the Levesons’ Staffordshire estates passed through the female line to the Gower (later Leveson-Gower) family, long-established in Yorkshire. They advanced through the peerage as Barons Gower (1703), Earls Gower (1746) and Marquises of Stafford (1786), until in 1833, having married the Countess of Sutherland, the 2nd Marquis was created Duke of Sutherland. At that time the Duke and Duchess were the largest private landowners in Britain.

During the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the Leveson-Gowers treated North Staffordshire as their personal fiefdom, which effectively it was. Earl Gower (later the first Marquis of Stafford) invested in mineral extraction and employed James Brindley to survey for the Trent & Mersey Canal. On his death in 1803 his second son Earl Granville took over the family’s interests in Staffordshire. In 1839 the 4th Earl Granville established an iron works at Shelton, where he was already mining coal. The 5th Earl established new works at Etruria in 1850 and created the Shelton Bar Iron Company. Many other industrial ventures in the district were either initiated by the Leveson-Gowers or undertaken on land leased from them. At least their activities in Staffordshire brought visible benefit for the population. In Scotland, the 2nd Marquess (formerly Elizabeth, Countess of Sutherland) is remembered as one of the instigators of the Highland Clearances, effectively destroying the traditional highland way of life and resettling thousands of families and replacing them with sheep.

Trentham Hall in 1880 from ‘Morris’s Seats of Noblemen and Gentlemen’. The front entrance is at the left, leading into the three-storey main house. The two-storey family wing is at the right, beyond the campanile. (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)

Much of the family’s wealth found its way back to Trentham. Having been expanded around 1700, Trentham Hall was again remodelled in the 1740s, including significant additions to the gardens. But even greater things were to come. In 1759 the 2nd Earl Gower commissioned the acclaimed landscape designer Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown to transform Trentham. Over the next twenty-one years he had an enormous impact on the estate. The lake was enlarged; the park wall was repaired and expanded; Tunstall Fields, to the west of the hall, was turned into parkland; and two neoclassical lodges were built at the south-west end of the lake with a sunken fence to separate the lawn from the deer park. The house, too, was re-designed by the architect Henry Holland.

But even this was not enough. With money flowing into the Sutherland’s coffers, the 2nd Duke instigated yet another rebuilding programme. It was led by the leading architect of the age and produced one of the largest country seats in England, with an equally elaborate and highly acclaimed garden. Yet within fifty years of its completion the whole thing had been flattened (see box below).

THE TRAGEDY OF TRENTHAM HALL

After the death of George Granville, 1st Duke of Sutherland in 1833 his successor George Granville, 2nd Duke of Sutherland, along with his wife Duchess Harriet, embarked upon an extensive rebuilding of the Trentham estate. Celebrated architect Sir Charles Barry, who designed the Houses of Parliament, was engaged to lead a £123,000 building programme. Barry extensively redesigned the hall including rebuilding the dining room and conservatory, as well as putting a belvedere tower over the old kitchen. The orangery, sculpture gallery and clock tower were added and in 1842 he remodelled Trentham church.

Perhaps Barry’s greatest achievement was the Italian Flower Gardens. Divided into three terraces, the gardens were flanked on the east by a wrought-iron trellis and on the west by a shrubbery. Barry created the shape and form of the Italian Gardens but he was no plantsman and the celebrated innovative planting schemes were the work of head gardener George Fleming.

However, the Hall’s proximity to the intensive industries of the Potteries did not make for a comfortable co-existence. In 1872 gardening journalist D.T. Fish reported that the River Trent was ‘the foulest blot on Trentham’ describing ‘a foul slimy sewer, brimful of the impurities of every dirty crowded town that hugs its banks’. Sadly the Trent also provided water to Trentham’s lake and its fountains, which meant the once beautiful features were ruined by the stench of brown sewage.

As pollution increased, Trentham’s allure waned. In 1905 the then Duke and Duchess abandoned the house and offered it to the Borough Council. After due consideration it politely declined. Trentham Hall was sold for recovery of the materials to a local builder and promptly demolished. The contents of the house were sold off for a paltry £500.

The site re-opened to the public in the 1930s following the formation of Trentham Gardens Ltd to maintain and manage the gardens. A new ballroom was built, as well as an art deco outdoor swimming pool by the lake. After being used for war work between 1939 and 1945, post-war Trentham established itself as a venue for dances and entertainment. Several attempts at restoration during the 1970s and 1980s had to be abandoned. Eventually, in 1996, a £100 million regeneration scheme was approved that has restored the historic estate and gardens into a popular tourist and leisure destination.

The return of the estate to active use for the people of Stoke-on-Trent and the nation is to be welcomed, but the wilful loss of Charles Barry’s Trentham Hall – one of the country’s most notable Victorian houses – remains an enduring tragedy.

The Leveson-Gowers and the Sneyds were at the apex of a pyramid of county families. Others with influence within the district were the Bowyers family of Knypersley Hall, the Batemans of Biddulph Grange, the Foley family of Longton Hall and the Swinnertons of Butterton Hall, near Newcastle-under-Lyme. The latter passed into the Pilkington family after Mary Swinnerton married Sir William Pilkington, 8th Baronet in the late 1700s. Many of these gentry families were ‘nouveau riche’, having made their money in pottery or other industries. Early pioneers Josiah Wedgwood and Josiah Spode established themselves at Etruria Hall and Fenton Hall respectively (the Spodes later moved to The Mount, Penkhull). Meanwhile, the Davenports extended and transformed both Westwood Hall, near Leek, and Wootton Hall, near Ellastone. At various times, Maer Hall was owned by both the Wedgwoods and the Davenports. Other industrialists in the area included the Kinnersly family at Clough Hall, Kidsgrove, who were bankers and iron merchants from Newcastle-under-Lyme. Hardly any of these country seats survive. Walton & Porter (2006) describe the fate of the district’s lost houses and the Lost Heritage website has photographs of some of them (www.lostheritage.org.uk).

The most important source for studying land and property during the eighteenth century is land tax. Introduced in the early 1700s, this became an annual tax levied on all landowners holding land with a value of more than 20s. per year. The surviving documents consist of assessments and returns and show the owners of real estate in each parish. From 1772, the returns were altered to include not just the owners but all occupiers/tenants of land and property in the parish with the exception of paupers. Most documents survive from 1780 to 1832, a period when the returns were used to establish a person’s entitlement to vote and were in effect electoral registers. From 1780, duplicate copies were lodged with the Clerk of the Peace and are now found among Quarter Session records [Q/RPl]; these are available at the SRO on microfilm.

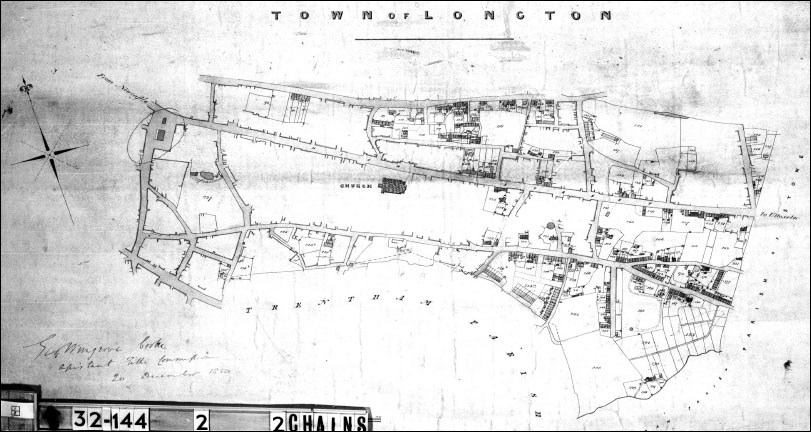

Tithe map of Longton, c. 1840, showing the allotment of land holdings. (The National Archives)

From 1788 land owners were able to commute their tax payments into a one-off payment but their names were still recorded each year. As part of the process a near complete listing of all occupiers and owners for the whole country was compiled in 1798 and can be found at TNA [Class IR 23, with related records in IR 22 and IR 24]; these are online at Ancestry.

The Tithe Commutation Act of 1836 reformed the system of tithes that had been levied on farmers and landowners since the Middle Ages, whereby they paid one-tenth of their annual produce to the church. The Act allowed tithes to be converted into cash payments, called tithe awards. New maps were drawn up to show who owned each field and property, along with a schedule (known as an apportionment) listing all the owners and tenants, and what each plot of land was worth. Tithe Commissioners administered and collected the annual payments, which were based on land values and the price of corn. Records were made in triplicate: one for the parish, one for the diocese and one for the Tithe Commission.

For Staffordshire, parish and diocesan copies, often including pre-1836 parish tithe lists, are at either the SRO or William Salt Library; those of the Tithe Commission are at TNA [Classes IR 29 and IR 30]. SSA Guide to Sources No. 3: Tithe Maps and Awards is a handlist of local holdings. Staffordshire Name Indexes has a searchable index of the awards themselves (1836–45): searches show information such as owner’s name, occupier’s name, township and parish, and plot name and number. It is proposed to digitize the tithe maps and make them available online; similar maps for the whole country are already available at TheGenealogist subscription website (www.the genealogist.co.uk).

Glebe terriers were surveys of the Church possessions in the parish, listing houses, fields and sums due in tithes. For Staffordshire, most surviving terriers date from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and are held within the former Lichfield Record Office collection. Transcripts have been published by the SRS as Staffordshire Glebe Terriers 1585–1884. Part One – Abbots Bromley to Knutton (Collections, Fourth Series, Vol. XXII (2008)); and Staffordshire Glebe Terriers 1585–1884. Part Two – Lapley to Yoxall (Fourth Series, Vol. XXIII (2009)).

The window tax was one of many obscure taxes levied during the eighteenth century. Introduced by William III as a replacement for the much-despised hearth tax, it imposed a flat rate tax per dwelling, initially at 2s. per house. Houses with between ten and twenty windows paid an additional 4s. and those with more than twenty paid another 8s. Some householders blocked up windows so as to reduce their tax liability. The tax was payable by the occupier of a property rather than the owner and those not paying the church or poor rate were exempt. From 1784 it was combined with the house tax. The SRO has returns from various dates for Trentham [D593/N/2/16], Newcastle-under-Lyme [D1798/618/227-228] and Totmonslow North [D3359/12/1/217].

The enclosure of agricultural land effectively broke up the smallholding system of farming and consolidated vast open shared tracts of land in the hands of wealthy landowners. The process began in the twelfth century but became widespread from 1750. Under a legal process known as Inclosure, open land was allotted to landowners by private Acts of Parliament and later by the Inclosure Acts between 1801 and 1845. These Acts list the landowner who brought the case to Parliament, while the enclosure award details how the land was to be divided up between the landowner and others, together with the amounts of land. In addition, a map of the land under investigation as part of the enclosure process might survive with the names of the landowners written on them. The SRO has surviving records for Staffordshire under Inclosure (Awards, plans, tithe agreements and exchanges) [main series under Q/RDc]; copies are often found in family papers, parish documents, and other collections. SSAS Guide to Sources No. 5: Staffordshire Enclosure Acts, Awards & Maps is a guide to holdings. An academic project has produced an electronic catalogue and directory of enclosure maps for England and Wales (http://enclosuremaps.data-archive.ac.uk).

Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent Archives holds a huge collection of records and papers relating to the estates of the Leveson-Gower family. The index runs to 9,600 entries and is likely to refer to tenants or others who had dealings with the estate. Examples include: Agents’ annual accounts, 1837–8, 1843–4; North Staffordshire Farm Rentals, 1812–57; Knowles Colliery, time and wages books, 1787–1802; and Lightwood Cottage Rentals, 1813–57. The Sutherland Collection has its own website (www.sutherlandcollection.org.uk) with information and articles about the family; and Staffordshire Name Indexes has a downloadable index for this collection.

The Sneyd Family Papers at Keele University comprise manorial, estate, legal and business records about the family, as well as watercolour and pencil sketches (www.keele.ac.uk/library/specarc/ collections/sneydfamily). The family’s nineteenth-century correspondence is particularly rich and survives in greatest volume.

Other major family and estate collections covering the district (many held by the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery) are: Adams family of Hanley, Cobridge and Newcastle-under-Lyme [SD 1256]; Davenport family of Maer Hall and Westwood Hall [D3272]; Heathcote family of Longton [SD4842/11]; Broade family of Fenton Vivian [SD4842/12]; Wedgwood family of Burslem and Bignall End [SD4842/13-16]; Wood family of Burslem [SD4842/16]; and the Swinnerton family of Butterton Hall [SD4842/17]. All contain items such as deeds, rentals, mortgages, leases and agreements, sales particulars, estate correspondence, plans and accounts. These and other collections are summarized in the Guide to Staffordshire Family Collections, published by the SSA.

Solicitors’ records are much under-rated but can contain a wealth of information, not just on large estates but also on town properties and tenants. Two important examples are the firms of Rigby, Rowley & Cooper [D3272] and Knight & Sons [D4452], both of Newcastle-under-Lyme. Mortgages, conveyances, wills, deeds, tenancies and leases, marriage settlements: all of these can end up in solicitors’ records. However, as the family may have used a solicitor some distance away (or firms may have moved), a broad search may need to be made. Auctioneers’ catalogues and sale notices in newspapers can provide a snapshot of an estate, or part of an estate, at the point when it was sold. Sometimes deeds can be found within the Quarter Sessions records under Enrolments (Deeds, Wills and Papists’ Estates) [Q/RD].

Those in the upper echelons of society will have been listed in the many directories of the peerage, baronetage and landed gentry published from the eighteenth century onwards by publishers such as Burke and Debrett; copies are available via the Internet Archive and other digitization initiatives.

Staffordshire Name Indexes has a database of Copyhold Tenants of the Manor of Newcastle-under-Lyme, 1700–1832 based on Roden (2008). Those with copyhold tenure over property had to record ownership through registering in the court roll. The property concerned was concentrated in the townships of Penkhull and Boothen, Clayton and Seabridge, Hanford, Hanley, Shelton and Wolstanton.

Mills were a key part of many rural communities. The Mills Archive holds a wealth of information about people connected with mills and milling, together with a separate database of mills across the country (www.millsarchivetrust.org). It includes extracts from the Staffordshire Advertiser for the 1830s and 1840s regarding mills for sale and to let, notices of bankruptcy and insolvency, and miscellaneous references to mills and millers.

Under Acts of 1710, 1784 and 1785 those shooting or caring for game had to have a licence. The SRO has a long series of registers for gamekeepers from 1784 to 1934 under Game Preservation and Taxation [Q/RTg].

Cooper, Gary, Farmers and Potters: A History of Pre-Industrial Stoke on Trent (Churnet Valley Books, 2002)

Durie, Bruce, Understanding Documents for Genealogy and Local History (History Press, 2013)

Roden, Peter, Copyhold Potworks and Housing of the Staffordshire Potteries, 1700–1832 (Wood Broughton Publications, 2008)

Walton, Cathryn and Lindsey Porter, Lost Houses of North Staffordshire (Landmark Publishing Ltd, 2006)

Westcott, Brooke, Making Sense of Latin Documents for Local and Family Historians (Family History Partnership, 2014)