Since the modern army began to take shape in the mid-eighteenth century, Staffordshire has been closely associated with the two regiments that bore its name. In particular, the historic North Staffordshire Regiment (Prince of Wales’s) recruited extensively from the local area during the First World War and was involved in many high-profile campaigns.

The North Staffordshire Regiment was formed in 1881 through the merger of the 64th (2nd Staffordshire) Regiment of Foot and 98th (Prince of Wales’s) Regiment of Foot, both of which had affiliations to the county. These two regular regiments became the new unit’s 1st and 2nd Battalions, respectively. The Militia and Rifle Volunteers forces of North Staffordshire were also incorporated into this new regiment (see below, p. 185). A permanent depot was established at Whittington Barracks, Lichfield, which also housed the newly formed South Staffordshire Regiment.

The 64th Regiment of Foot was originally raised in 1756 as the 2nd Battalion of the 11th (Devonshire) Foot, and was renumbered the 64th in 1758. It served in the West Indies during the Seven Years War, America during the American War of Independence, and South America, the West Indies and Canada during the Napoleonic Wars. Subsequent long periods were spent in Ireland and the West Indies before action was seen in India during the Indian Mutiny. The 98th Regiment of Foot, raised in 1824 in Chichester, had a much shorter history, but like the 64th had spent the majority of its time overseas. It served for a long period in South Africa before seeing action in China in the First Anglo-Chinese (or Opium) War and India on the North West Frontier.

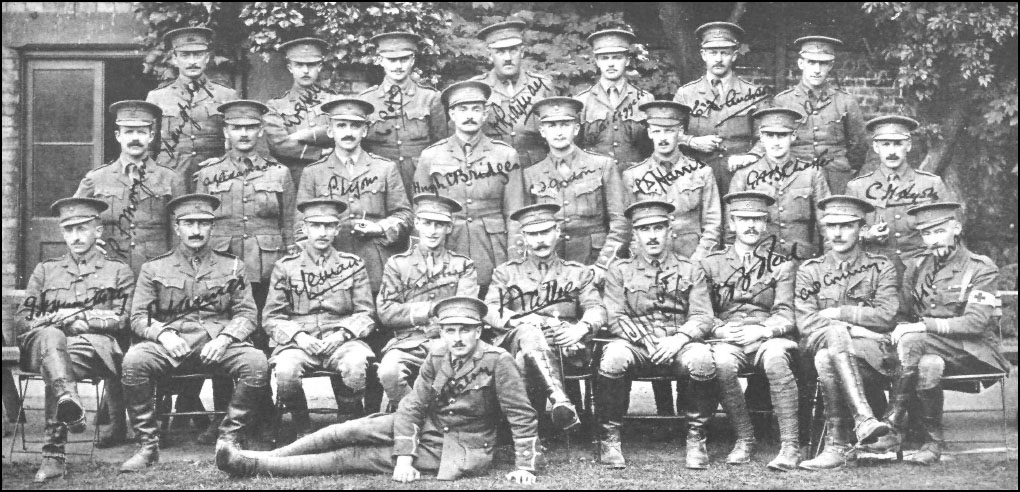

Officers of the 1st Battalion, North Staffordshire Regiment, shortly before embarking for France in Cambridge, August 1914. Of those who sailed, only five were still with the battalion in January 1915, most of the remainder having been killed or wounded. (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)

The North Staffordshire Regiment was heavily committed to the fighting during the First World War. In addition to the two regular battalions several territorial and service battalions were deployed. The battalions that served in France took part in many of the major actions of the war including the 1915 Battle of Neuve Chapelle, the 1915 Battle of Loos, the Battle of the Somme in 1916, the Third Battle of Ypres (generally known as the Battle of Passchendaele) in 1917, and the Battle of Amiens in 1918.

After the Armistice, the 1st Battalion was posted to Curragh, Ireland, becoming involved in the Irish War of Independence until 1922, when it moved to Gibraltar. In 1923 it was posted to India and remained in the Far East until 1948. The 2nd Battalion was initially stationed in India after the war, and later spent time in Gibraltar (1930–2) and Palestine (1936–7). In 1921, the regimental title was changed to The North Staffordshire Regiment (The Prince of Wales’s).

Throughout the Second World War the 1st Battalion served in India and Burma, while the 2nd Battalion remained in Italy and North Africa. The North Staffordshire Regiment was awarded twenty-two battle honours during the conflict.

It continued to perform in peace-keeping roles up to its amalgamation with the South Staffordshire Regiment in 1959.

The South Staffordshire Regiment was formed in 1881 through the merger of the 38th Regiment of Foot and the 80th Regiment of Foot, which also had Staffordshire affiliations. The 38th Foot, the new unit’s 1st Battalion, served in Malta and Sudan, while the 80th Foot, the new 2nd Battalion, spent time in Egypt and India. After deployment to South Africa during and after the Boer War, both battalions served in France for most of the First World War. The regiment also raised eleven Territorial and New Army battalions during the conflict.

During the Second World War the 1st Battalion saw action in Palestine and Burma, while the 2nd Battalion fought in Tunisia, Sicily, Italy and at Arnhem. After the war it was granted an arm badge showing a glider in recognition of its service in an air-landing role.

Following a defence review, in 1959 the North Staffordshire Regiment (The Prince of Wales’s) and the South Staffordshire Regiment were merged to form The Staffordshire Regiment (The Prince of Wales’s). Under subsequent reorganizations, this became the 3rd Battalion, The Mercian Regiment (Staffords). The regimental museum is at Whittington Barracks, Lichfield (www.staffordshireregiment museum.com).

A list of regimental histories for Staffordshire, including yeomanry and militia units, was published in the June 2000 edition of the Midland Ancestor (Midland Ancestors). GENUKI’s Staffordshire pages have an extensive military bibliography (www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/STS).

English militia were part-time military units established at county level for home defence. After a dormant period following the Civil War, they were reinstated by the 1757 Militia Act. The men would receive basic training at annual camps and be available to be called up in times of national emergency. When volunteers proved insufficient, a parish selected men by ballot. These men then either served or found a substitute to take their place.

In Staffordshire the militia is known to have existed since at least the seventeenth century. It was embodied as required and had units known by various names and titles. In 1797 the Staffordshire Militia was inspected by George III. He was so impressed with the regiment’s smart appearance that he ordered it to Windsor Castle to take up royal duties. It was stationed there again in 1799, 1800 and 1801, when it was disembodied. The king expressed great regret at its departure; however, when hostilities with France were renewed in 1803, the regiment was reformed and ordered back to Windsor. It was welcomed by the king in person, who led it to the barracks. In 1805, George III granted the regiment the additional honour of ‘The King’s Own’ in its title. As a royal regiment the facing colour of the uniform was then changed from yellow to royal blue. The regiment left Windsor in 1812, and was again stood down in 1814. It was re-embodied for a matter of some months in the following year, after Napoleon’s escape from Elba.

At the time of the formation of the North Staffordshire Regiment in 1881 four militia and volunteer units were taken into the new regiment, each forming a separate battalion. These were: the King’s Own (2nd Staffordshire) Light Infantry Militia (which became the 3rd (Militia) Battalion, based in Stafford); the King’s Own (3rd Staffordshire) Rifles Militia (4th (Militia) Battalion, based in Newcastle-under-Lyme); 2nd Staffordshire (Staffordshire Rangers) Rifle Volunteer Corps (1st Volunteer Battalion, based in Stoke-on-Trent); and 5th Staffordshire Rifle Volunteer Corps (2nd Volunteer Battalion) based in Lichfield but later moved to Burton-on-Trent.

Together with the Volunteer battalions of the South Staffordshire Regiment, the new 1st and 2nd Volunteer battalions formed the Staffordshire Volunteer Infantry Brigade in 1888. This brigade was intended to assemble at Wolverhampton in time of war, while in peacetime it acted as a focus for collective training of the Volunteers.

The formation of the Territorial Force in 1908 regularized links between the old county militias and volunteers and their regular army counterparts. At that time the South and North Staffords each had six battalions: two Regular, two Militia and two Territorial. The North Staffordshire Regiment’s two Volunteer battalions were renumbered as the 5th and 6th battalions, forming part of the Staffordshire Brigade in the North Midland Division.

Staffordshire Record Office has militia lists for various dates and locations, including Staffordshire Yeomanry, 1804–1946 with gaps [D1300]; North Staffordshire Local Militia returns, 1810–19 [D1788]; Trentham Loyal Volunteers, 1803 [D1554/161]; and Newcastle Volunteers Armed Association, 1819 [D1460]. TNA has a long run of Staffordshire militia lists from across the county, 1781–1876 [in class WO 13]; Gibson & Medlycott (2013) has further details or consult the TNA Discovery catalogue. The militia list for the 1st Staffordshire, 1781–2 has been published in County Militia Regimental Returns (www. fhindexes.co.uk); a transcript is available on the STCA Search Room computers. Anderton (2016) lists the names of men who joined home defence units in North Staffordshire at the height of the Napoleonic Wars. Midlands Historical Data has histories for some of these militia and early territorial units (www.midlandshistoricaldata.org).

When the First World War broke out in August 1914 the Potteries, like many towns and cities, answered Lord Kitchener’s call for volunteers to enlist. Across the country, over 100,000 rushed to sign up within the first two weeks. Within the Six Towns men gathered at recruiting stations to join up: the main station was at Stoke Town Hall. The North Staffordshire Regiment’s official history recounts that: ‘The streets round it were crowded with men, and inside the buildings were masses of men struggling to be accepted and passed by the doctors. It was an unforgettable sight.’

North Staffordshire Regiment cap badge. (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)

The ranks of the 5th North Staffords, the original territorial unit, were soon swelled, as the depot at Shelton was overrun by new recruits, all desperate to serve king and country. ‘They were of all classes and occupations, and were the pick of the youth from the neighbourhood. A large contingent consisted of men who had been educated at the Newcastle High School.’

Leaving their new recruits behind, on 11 August 1914 the 5th North Staffords marched from Hanley to Burton, passing through Stoke, Meir, Blythe Bridge, Tean and Checkley. As they rested in a field near Checkley, their commander-in-chief, Lieutenant Colonel John Hall Knight, read a telegram asking them to volunteer for foreign service. The men unanimously agreed (as if they had a choice!) and Knight sent a telegram back to the War Office offering the battalion’s services abroad.

The 1st/5th North Staffords was one of six Territorial Force battalions added to the North Staffordshire Regiment during the First World War, and the one most closely associated with the Potteries. In addition, eight Service and Reserve battalions were raised. Together with two regular and two pre-existing Reserve battalions, this swelled the number of North Staffordshire battalions to eighteen.

The 1/5th and 1/6th Battalions were among the first Territorial Force units to go to France, arriving in February and March 1915. They fought in the Battle of Loos in 1915, as well as at Gommecourt on the northern flank of the Battle of the Somme. The 1/5th was disbanded in January 1918 and the men dispersed to other units. Part of the 1/6th Battalion was involved in the celebrated action to seize the Riqueval Bridge over the St Quentin Canal in September 1918. Their commanding officer, acting Captain A.H. Charlton, was decorated with the Distinguished Service Order. Altogether, the regiment was awarded fifty-two battle honours during the First World War.

Staffordshire Name Indexes has a database of over 13,000 photographs of soldiers published in the Staffordshire Weekly Sentinel newspaper (www.staffsnameindexes.org.uk). These are typically head and shoulder shots in pictures about the size of a cigarette card. The photographs would have been provided by the soldier’s family on a voluntary basis and would generally have been accompanied by a news item. Their publication may relate to the fact that the man in question was missing, wounded, taken prisoner, in hospital, or been recognized for gallantry and was not necessarily a fatality. The STCA has the original newspapers on microfilm (see Chapter 1).

The capture of Riqueval Bridge, 1918 where the 1/6th Battalion North Staffords saw action. (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)

Major Edward Blizzard, managing director of a brick and tile manufacturer in Hanley, became North Staffordshire’s principal recruiting officer during the conflict. The SRO has his scrapbooks, which include the story of Lance Corporal William Coltman, VC, the most highly decorated NCO of the First World War [SRO: D797/2/2].

Capper (2014) is an authoritative history of the regular 1st and 2nd Battalions of the North Staffordshire Regiment during the First World War. Sheldon (2004) describes the experiences of men from Leek who fought and died in the conflict. Jeffrey Elson’s two books document personnel from both Staffordshire regiments who have been decorated since 1914 (Elson, 2004 and 2014). STCA has records from the North Staffordshire Regiment Reunion Association, 1926–76 which includes membership books [SA/NSRA]. Commercial websites have extensive series relating to military personnel including service records, pension records, medal cards, gallantry citations and mentions in dispatches, and soldiers’ wills.

As soldiers risked their lives on the front line, for their families and friends left at home life too was hard. This was the first time that civilians were a crucial part of a new kind of warfare. Even though men, women and children in Staffordshire were far from the guns, the authorities recognized that forming a resilient home front could make the difference between winning and losing the war.

With food in short supply, lengthy queues formed at shops. Drawn by the rumour of supplies, women and children gathered early in the morning to queue for scarce goods like sugar, margarine and tea. The government feared food shortages could spark riots. Zeppelins were seen over Staffordshire and conscientious objectors, such as Edwin Wheeldon of Burton, faced gaol for their beliefs.

Hunt (2017) describes life on the home front in Staffordshire during the First World War. The book is based, in part, on papers from the Mid-Staffordshire Appeals Tribunal, a body that heard appeals against military conscription [SRO: C/C/M/2/1-35]. The records of Military Appeals Tribunals were ordered to be destroyed after the war and the survival of those for Staffordshire is believed to be unique. Military tribunals were also reported in the Staffordshire Advertiser, which gives details of the cases being heard but does not give the names or addresses of those involved.

The Great War Staffordshire website served as a portal for the 1914–18 Centenary celebrations in the county and is likely to remain active for the foreseeable future (www.staffordshiregreatwar.com). It includes details of the Staffordshire Great War Trail which was created to connect the county’s principal landmarks related to the First World War. These include the National Memorial Arboretum at Alrewas; Cannock Chase Commonwealth War Cemetery; and the Staffordshire Regimental Museum, where there is a replica First World War trench.

When the twentieth century’s second great conflict came, the Potteries found itself in the front line. Not being a centre for armaments manufacture or other heavy production, the district avoided the blanket bombing suffered by some other areas. But German planes could often be seen over North Staffordshire en route to Manchester, Liverpool, Crewe and other prime targets.

There were around twenty recorded bombings across Stoke-on-Trent and North Staffordshire itself. The main targets were the Michelin and Dunlop tyre factories, the railway goods yard, the British Aluminium Works at Milton and the munitions factory at Radway Green. In January 1941 bombs fell in Old Stoke Road during a raid targeted at the Michelin works. Dorothy Hordell, who worked at Dunlops in Etruria, recalled bombing raids over Hanley for the BBC’s People’s War Archive (www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/ categories/c1152/):

I used to sit and watch the German planes go over. They were after the aluminium works down Birches Head Lane and the steelworks at Etruria. They used to follow the canal that low you could see the markings on them. They came over one night and dropped a basket of incendiary bombs on Birches Head Lane. It seemed the world was on fire and everybody was running for cover. I can’t remember the fire brigade coming out. Our planes chased off the Germans. One German plane dropped one bomb that went through an air raid shelter up Campbell Terrace in Birches Head. Nobody was killed. They had a lucky escape they did.

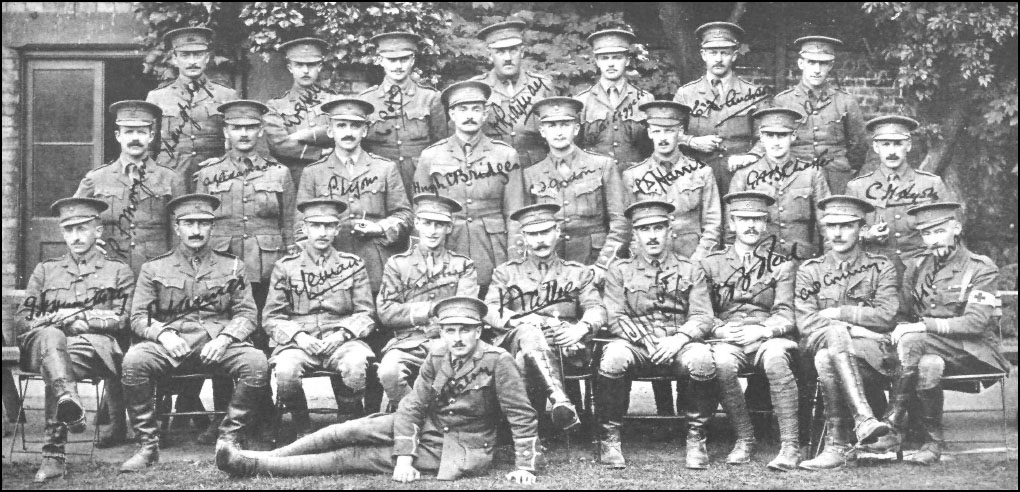

Air raid damage at Chesterton, 14 December 1940. (Staffordshire Past Track)

One of the worst attacks was on Saturday, 14 December 1940 when a lone German raider attacked Chesterton, Newcastle-under-Lyme. Sixteen people are thought to have been killed, including several family members and evacuees from London. The Salvation Army Hall, which was fortunately unoccupied at the time, took a direct hit. On another occasion a bomb was dropped on Leek, apparently by accident.

Evacuation was introduced in order to protect children. Staffordshire was initially viewed as a ‘neutral’ location, meaning it was neither likely to receive evacuees nor send children out of the county. Later it was redefined as a reception area.

Evacuation to Staffordshire occurred in two waves. During the early stages of the war, under Operation Pied Piper, over 8,000 unaccompanied children were evacuated to the county from nearby cities such as Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool. Most of these soon returned home when the anticipated bombing of cities did not materialize. A second wave of evacuation was initiated in 1940 and increased after the start of the Blitz. This time evacuees came to the county from all over Britain. Often they were evacuated with their school and accompanied by teachers. There were also children who were evacuated privately by their families to live with local relatives or friends. Many of these evacuees experienced a different way of life in Staffordshire’s towns and rural communities to the one they were used to.

The Staffordshire Past Track portal has photographs of bomb damage and other aspects of life in Staffordshire during the Second World War (https://tinyurl.com/ya88fgzc). The Children on the Move website and associated book document the experiences of evacuees and host families in Staffordshire and provide extensive learning resources for schools (www.childrenonthemove.org.uk).

In May 1940 the government broadcast a request for Local Defence Volunteers, the intention being to create a part-time civilian army to defend against any invasion. Within a few days several thousand men had volunteered in North Staffordshire. They were organized into six Home Guard Battalions covering all parts of the district. The 1st Staffordshire Battalion covered Stoke; 2nd Staffordshire covered Burslem; 3rd Staffordshire covered Longton and Meir; and 4th Staffordshire covered Hanley. These four Battalions formed No. 1 Group of No. 3 Zone of the West Lancashire Area. Further afield were the 5th Battalion in Leek and the 6th Battalion in Cheadle.

Although held together initially by little more than their own enthusiasm, organization was quickly tightened up and the Home Guard began to establish itself. The 2nd Staffordshire Battalion, for example, was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Reg Brown, a Captain Mainwaring-type character who had served in submarines from 1916–19 and then, with his brother, had set up Browns Motor Company in Tunstall.

Towards the end of 1941 many factories began to form units drawn from their personnel, initially for the purpose of protecting their own premises. One such was the Royal Ordnance Factory at Swynnerton (see below).

The Staffs Home Guard site describes the British Home Guard and specific Home Guard units across the country and is particularly detailed for Staffordshire (www.staffshomeguard.co.uk). The STCA has a reprint of the Home Guard List 1941 for Western Command, a rare document that lists all serving Home Guard officers (Savannah Publications, 2005). The Staffordshire Past Track portal has pictures related to the local Home Guard and the Air Raid Precautions. The BBC’s People’s War Archive for Stoke and Staffordshire has recollections of local Home Guard activities (web address as above). Staffordshire University has the Iris Strange Collection, comprising personal and official letters and documents relating to the position of Second World War widows.

The Luftwaffe’s failure to knock out the Royal Air Force in the Battle of Britain owed much to the ground-breaking design of the Spitfire aircraft, designed by Potteries-born R.J. Mitchell (see box below). The Spitfire played a decisive role in defending the country and at one point more than 500 aircraft per month were being produced.

As noted above, other locations central to the war effort were the Michelin and Dunlop tyre factories, the Shelton steelworks and various ordnance and munitions factories. One of these was at Mill Meece, Swynnerton, between Newcastle-under-Lyme and Stafford. Construction work started in 1939, with production beginning the following year. Large numbers of people were employed, peaking at 18,000 in 1942. The factory’s function was mainly the filling of ammunition cases with explosive. Such was its size and importance that a dedicated branch railway line was built to serve it. The City Surveyor’s Collection at the STCA has maps of bomb damage and Air Raid Precautions from the period (see Chapter 1).

Planes at Meir Aerodrome. (Public domain)

In 1934 Stoke-on-Trent City Aerodrome had opened at Meir. It was the first of three municipal airports constructed in Staffordshire during that period, the others being at Walsall and Wolverhampton in the south of the county. From 1939 Meir became an RAF station where novice pilots were trained. Beaufighters and Blenheim bombers assembled at the nearby Rootes factory at Blythe Bridge were also flown from Meir. As the number of air bases across Staffordshire proliferated, American GIs and pilots became a common sight in the Potteries.

After the war, activities at Meir were largely confined to glider training for Air Training Corps cadets, although Staffordshire Potteries flew aircraft in the 1950s and the Staffs Light Plane Group continued until the 1970s. However, Meir was doomed from the start by its location close to a densely populated area, the sloping ground and an industrial haze which created visibility problems. The last plane took off in 1973 and the site was subsequently developed for housing. Brew (1997) has a more detailed history.

Many of the country’s most important institutions and cultural assets were moved out of London during the war to escape air raids on the capital. Almost as soon as war broke out the Bank of England relocated to Trentham Gardens, the former home of the Duke of Sutherland. All the major clearing banks had staff there, each bank occupying its own section in the ballroom and the foreign section on the stage. A lot of the staff were moved up from London and billeted in the local area. Many experienced profound cultural shock, being used to the big city. They tended to keep to themselves and took to calling themselves ‘the Outcasts’.

REGINALD J. MITCHELL: FATHER OF THE SPITFIRE

Reginald J. Mitchell was one of the great designers and engineers of the twentieth century.

He was born in Butt Lane, near Stoke-on-Trent in 1895. He trained as an engineer and then joined the Vickers Armstrong Supermarine Co. in 1916, rapidly becoming chief designer. During the 1920s and early 1930s he designed sea-planes, creating revolutionary designs, such as the Supermarine S6, which set speed records and won the Schiedner trophy in 1931. From these beautiful seaplanes, the Spitfire was born.

Reginald Mitchell, designer of the Spitfire. (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)

Among his many accolades, Mitchell was awarded the Silver Medal of the Royal Aeronautical Society and made an Associate Member of the Institute of Civil Engineers in 1929, the same year that he was awarded the CBE. Unfortunately, he did not live to see the success of his Spitfire in combat in the Second World War, nor even to see it fly in anger. He died of cancer in 1937, aged only 42.

R.J. Mitchell is commemorated at several locations. There is a plaque on the house where he was born at 115 Congleton Road, Butt Lane. The Mitchell Memorial Theatre (now the Mitchell Arts Centre) in Broad Street, Hanley was named after him in 1957. Most prominent is a statue that stands outside the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery in Hanley, while the museum’s Spitfire Gallery showcases the man and his aeronautical achievements.

The STCA has a register of Polish personnel working at W.H. Grindley & Co. in Tunstall, 1947–53, many of whom are likely to have arrived during the Second World War [SD 1332].

Men and women who fell in various conflicts are commemorated in memorials and rolls of honour across North Staffordshire. Each of the Six Towns has at least one war memorial, generally positioned outside the town hall or in a civic square. There are many more in churches, schools, businesses and public buildings, and in outlying towns and villages. These memorials and rolls cover several centuries in some cases, though concentrate mostly on the First World War and Second World War.

Researching Staffordshire’s Great War Memorials, published by SSA (2014), lists all of the county’s local war memorials and provides a guide to how to research them (available as a free download from www. staffordshiregreatwar.com). The STCA has the Roll of Honour Land Force, World War 2 (Vol. 5) which includes casualties from the North Staffordshire Regiment (Savannah Publications, 2002).

The Roll of Honour website has transcripts from memorials and rolls of honour across the country, including Staffordshire (www.roll-ofhonour.com). As well as later conflicts, it includes information about the Fenton and Hanley Boer War memorials. Civilian cemeteries in the UK containing war graves and memorials (although not individual names) are listed at the WW1 Cemeteries site (www.ww1 cemeteries.com). The National Railway Museum website has the roll of honour of railway employees from the conflict (www.nrm.org.uk). For those buried abroad see other sites, such as that of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (www.cwgc.org).

Midlands Historical Data publishes many military books on CD, including rolls of honour and regimental histories (Militia and Territorials as well as Regular units).

The Military Collection at Aldershot Public Library is a useful resource for those researching military ancestors. It comprises nearly 20,000 books, most available for loan, together with many specialist databases. The library staff will undertake searches for a nominal fee (http://tinyurl.com/nau9c24).

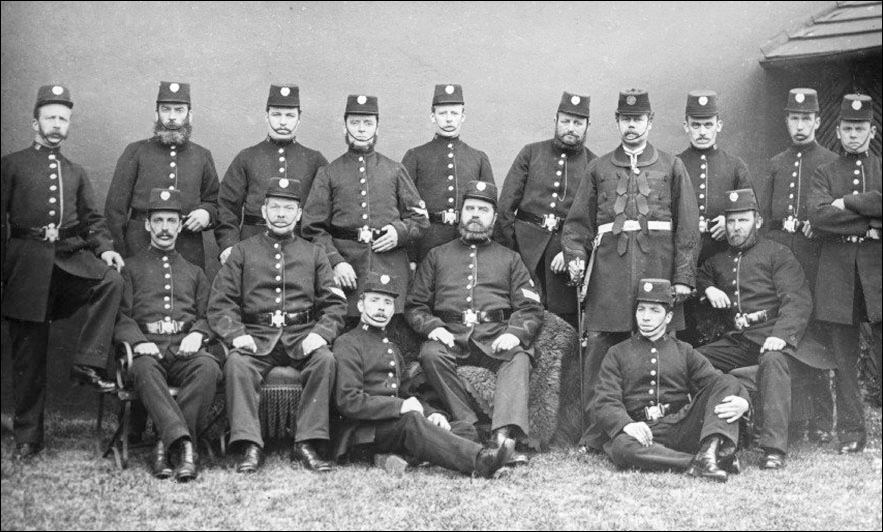

Before the early nineteenth century policing in England had relied on parish constables, members of the community who were elected by their fellow parishioners and took on a variety of local duties. In 1829 Sir Robert Peel formed the Metropolitan Police in London as the first paid professional police force. This professional model began to be adopted elsewhere. In North Staffordshire the first town to do so was Newcastle-under-Lyme which set up a borough police force in 1834. The following year, the Municipal Corporation Act of 1835 compelled all boroughs to establish a watch committee, and appoint head constables and other constables.

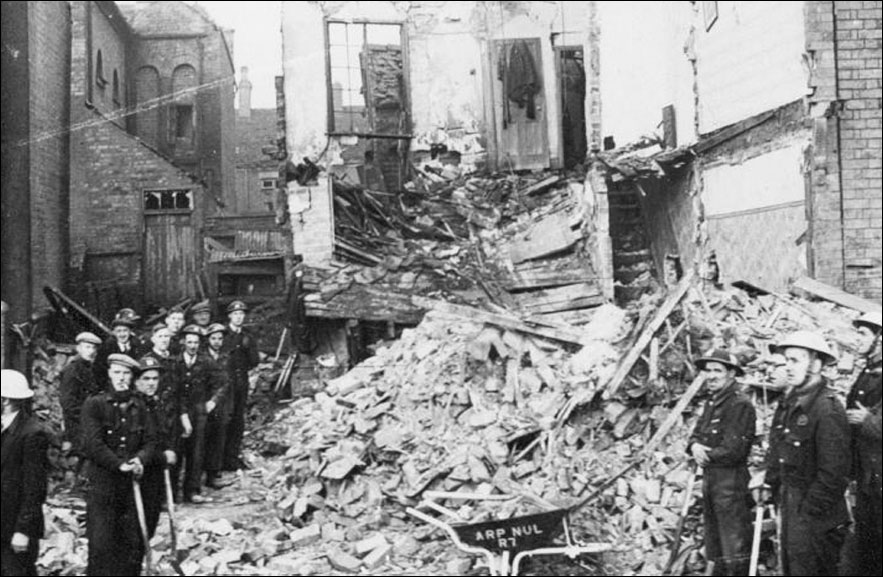

Newcastle Police, 1890s. (Public domain)

The Six Towns were exempt from these requirements, as none had yet been granted borough status (and would not be until Hanley incorporated in 1857). In the absence of the Towns’ own arrangements, it fell to the new Staffordshire County Constabulary to provide policing. A few officers and men (exact numbers are unknown) were stationed in Hanley from 1843, as part of the new Pottery Division. It was not until September 1870, thirteen years after becoming a borough, that Hanley set up its own watch committee and police force. At that time the new Hanley Borough Police had thirty-one men. Stanford Alexander, the Chief Constable of Newcastle-under-Lyme, was appointed to lead the force. He also took charge of the Police Fire Brigade: this was formed in 1871, reorganized in 1901 and survived until 1910 when the new County Borough took over responsibility for fire-fighting.

After federation in 1910, the force became known as Borough of Stoke-on-Trent Police and was renamed Stoke-on-Trent City Police in 1925. Women were first admitted in 1921 but numbers were capped at two policewomen for the next twenty years. Only in 1941, when police forces were ordered to relieve male officers for war duties, did numbers increase. Eventually, in 1968, Stoke-on-Trent City Police amalgamated with Staffordshire County Police to form a single county-wide force.

Tunstall & Cowdell (2002) describes the history of policing in the Potteries from the formation of borough police forces through to the 1968 merger. Many names are mentioned and its annex lists all of those serving on amalgamation.

Staffordshire Record Office has a complete series of County Police Force Registers, covering the period 1842–1977 [C/PC/1/6/1-2 and C/PC/12/1/29/3]. These contain the main personnel record for every officer who served in Staffordshire Police, giving information about the officer’s age and place of origin, appearance, career progression and reason for leaving the service. There is an online index to these holdings on Staffordshire Name Indexes. The SRO also holds police personnel records from 1920 to 1977, which may be consulted by special arrangement. Other police records at the SRO include registers of appointments and promotions, and superannuation registers which record the pensions paid to men who had left the service or gratuities paid to dependants.

The Staffordshire Constabulary Defaulters Register contains information about disciplinary offences committed by members of Staffordshire Constabulary, covering the period 1857 to 1886 and 1904 to 1923 [SRO: C/PC/15/1/1 and C/PC/29]. Many of the offences recorded relate to police officers’ over familiarity with undesirable elements of society, such as prostitutes, or to the abuse of alcohol. Again, Staffordshire Name Indexes offers an online index to these records.

Neither of the personnel records above cover borough police forces, such as operated in the Potteries. Hence, officers who served in Hanley from 1870 and in the rest of the Potteries between 1910 and 1968 are unlikely to be included, unless they also served with the county force. The records of Stoke-on-Trent Borough (and later City) Police, 1885– 1968 appear in the SSA catalogue under various headings: C/PC/6/1; C/PC/14; SD 1651; SD 1669, all of which are held at the STCA. These series include a register of applicants, 1909–26 [C/PC/14/22/2]; and a register of men from Staffordshire Police absorbed into Stoke-on-Trent Borough Police on its formation, 1910–19 [C/PC/14/22/4].

During the First World War many men signed up for roles in the Second Police Reserve, a body of volunteer police constables and the forerunner of the Special Police Reserve. This reserve helped to compensate for the loss of officers who enlisted to fight. The STCA has a register of those who signed up for the Stoke-on-Trent area [C/PC/14/22/5]. The register contains details such as previous service in the armed forces, address, year of birth, physical description and other notes, such as current employer and whether the men were willing to work unpaid or not. Many of those who joined the Second Police Reserve later left in order to enlist in the regular armed forces.

Another useful source is the Third County Force Register, 1894–1935 [SRO: C/PC/12/1/29/3], which relates to officers who joined the police reserve. A name index is also available [SRO: C/PC/12/1/29/4].

The former Staffordshire Police Museum at Baswich House closed in 2006 and its collections were transferred to the SSA [C/PC/12/19]. The Staffordshire Past Track portal has photographs relating to policing and firefighting in days gone by under the Law, Order & Emergency Services theme.

Anderton, Paul, Called to Arms 1803–12 in the Staffordshire-Cheshire Border Region: Volunteer Infantry Corps for Home Defence under Threat of a Napoleonic Invasion (Audley & District FHS, 2016)

Brew, Alec, Staffordshire and Black Country Airfields (History Press, 1997)

Capper, John, History of the 1st and 2nd Battalions, The North Staffordshire Regiment (The Prince of Wales’s), 1914–1923 (Churnet Valley Books, 2014)

Cooke, William, Wings Over Meir: The Story of the Potteries Aerodrome (Amberley Publishing, 2010)

Elson, Jeffrey C.J., Honours and Awards for the North and South Staffordshire Regiments 1914–1919 (Token Publishing, 2004)

Elson, Jeffrey C.J., Honours and Awards: The Staffordshire Regiments (Prince of Wales’s) 1919–2007 (Token Publishing, 2014)

Gibson, Jeremy and Meryn Medlycott, Militia Lists and Musters, 1757– 1876 (5th edn, Family History Partnership, 2013)

Hunt, Karen, Staffordshire’s War (Amberley Press, 2017)

Sheldon, C.W., Roll of Honour: The Story of The Hundreds of Leek Men who Fell in the First World War (Three Counties Publishing, 2004)

Tunstall, Alf and Jeff Cowdell, Policing the Potteries (Three Counties Publishing, 2002)