Across North America, there are more than 70 plant families that include trees—and more are found in Australia, Africa, Europe, China, and tropical areas around the world. While some of those families just include trees, smaller plants are also included—even wildflowers!

Here are some of the most common tree family groups. It helps to remember that these are plant families, and the members of a family may include trees, wildflowers, shrubs, and even vines.

Yew family. Yews have short evergreen needles, and a bright red berrylike cup surrounding each seed. Only two species of yews are found wild in North America. Species native (growing wild naturally) to other countries are grown for landscaping.

Yew family. Yews have short evergreen needles, and a bright red berrylike cup surrounding each seed. Only two species of yews are found wild in North America. Species native (growing wild naturally) to other countries are grown for landscaping.

Pine family. This includes the many species of pine, spruce, hemlock, and fir. These trees are usually called evergreens, because they look green throughout the year. But they do lose some of their needles every fall, and those get replaced in the spring with new growth.

Pine family. This includes the many species of pine, spruce, hemlock, and fir. These trees are usually called evergreens, because they look green throughout the year. But they do lose some of their needles every fall, and those get replaced in the spring with new growth.

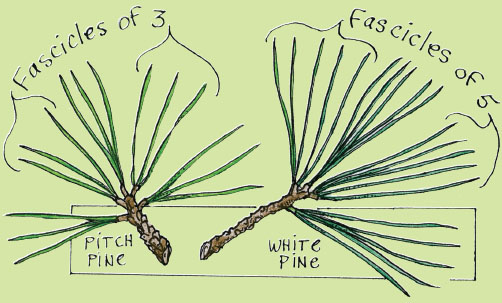

The long, thin leaves of pine trees are called needles. The needles grow from the twigs in clusters called fascicles (FAS-i-kils). The needles on a pitch pine grow in fascicles of three. You can remember that the needles of an eastern white pine grow in fascicles of five by remembering that the word white has five letters, w-h-i-t-e!

Other species of pines have needles in fascicles of three and five also. Some species have short needles, while others have long needles. Sometimes it’s hard to keep track of all the different types of pines! But it’s fun to get a start in observing the details of pine trees.

Botanists (scientists who study plants) call trees in the pine family conifers, because they produce woody, scaled cones with seeds inside. Conifers have cones of different sizes: white pines have cones about six to eight inches long, but the eastern hemlock has much smaller cones—less than an inch long.

The cones of an eastern hemlock.

Redwood family. The famous coast redwood of California and Oregon is a member of this family, along with the giant sequoia. Another member is the metasequoia, also called the dawn redwood. It is a native, wild tree in China but has been grown in nurseries and is sometimes planted around homes.

Redwood family. The famous coast redwood of California and Oregon is a member of this family, along with the giant sequoia. Another member is the metasequoia, also called the dawn redwood. It is a native, wild tree in China but has been grown in nurseries and is sometimes planted around homes.

Bald cypress family. This family includes many of the trees found in the swamps and marshes of Florida and the extreme southeastern United States.

Bald cypress family. This family includes many of the trees found in the swamps and marshes of Florida and the extreme southeastern United States.

Cedar family. One member of this family, the northern white cedar, is also called arborvitae (ar-bor-VY-tee). It is native to the northeastern states and southeastern Canada.

Cedar family. One member of this family, the northern white cedar, is also called arborvitae (ar-bor-VY-tee). It is native to the northeastern states and southeastern Canada.

A twig from a giant sequoia. The leaves are very small, pointed, and shaped like triangular arrowheads.

TRY THIS!

TRY THIS!

A pine tree can often be identified by the number of needles in a fascicle (cluster). It’s easy to find a fascicle and then count the needles.

MATERIALS

Your sharp eyes

Your sharp eyes

Pine twig with fascicles (clusters) of needles on it. You might find a twig or branch on the ground if there has been a lot of wind. You can also count fascicles on a small seedling or sapling pine—even if it’s only one or two feet tall!

Pine twig with fascicles (clusters) of needles on it. You might find a twig or branch on the ground if there has been a lot of wind. You can also count fascicles on a small seedling or sapling pine—even if it’s only one or two feet tall!

1. Look at the twig and find a cluster (fascicle) of needles. The fascicle is securely attached to the twig. Count how many needles there are.

2. Count two more fascicles, just to be sure they all have the same number of needles. (Some may have been damaged by storms or by insects.)

Look for other pines in your area to see if they have fascicles with the same number. There are more than 20 species of pines in North America, so you might have more than one species of pine in your neighborhood.

The pitch pine on the left has three needles in each fascicle. The eastern white pine on the right has five.

Larches are different than most other members of the pine family. Pines, hemlocks, firs, and spruces are evergreen all year long, but larches turn golden yellow in the autumn—and then all the needles fall off! Larches look very colorful in the fall, but they have bare branches all winter.

Larches are also called tamaracks or hackmatacks, names originally from the Algonquian Native Americans. Three species are found in North America. The most common one grows in the northeastern United States and across much of Canada. Larches can grow about 60 feet tall and have a pointed, triangular shape. The needles are short and grow in tight clusters, or even as single needles.

The needles of tamarack trees turn gold in the fall, and then all the needles fall off. Most other members of the pine family lose only some of their needles in the autumn.

The fan-shaped leaves of a ginkgo tree are easy to identify.

Ginkgo family. These trees are native to China, where they grow wild, but they have been grown and raised in North America for a long time. Their unique, fan-shaped leaves are easy to identify. Fossil leaves of ginkgos have been found dating to the Triassic period—more than 100 million years ago!

Ginkgo family. These trees are native to China, where they grow wild, but they have been grown and raised in North America for a long time. Their unique, fan-shaped leaves are easy to identify. Fossil leaves of ginkgos have been found dating to the Triassic period—more than 100 million years ago!

Although the ginkgo is a native wild tree in China, it is grown and planted throughout most of North America. The leaves turn yellow-gold in the fall. The rounded fruit has a large seed inside.

Palm family. This includes the coconut palm. Palms don’t have branches like other trees, but have a fountain-shaped tuft of big fronds (large leaves) at the very top. There are more than 1,000 species in this family around the world in tropical areas. Along with trees, this family also includes vines and small shrubs.

Palm family. This includes the coconut palm. Palms don’t have branches like other trees, but have a fountain-shaped tuft of big fronds (large leaves) at the very top. There are more than 1,000 species in this family around the world in tropical areas. Along with trees, this family also includes vines and small shrubs.

Willow family. Willows are widely known for their thin, drooping branches with narrow leaves. Black willows usually grow near rivers and ponds. Pussy willows are small, shrubby members of the family. Aspens, cotton-woods, and poplars are members with rounded leaves.

Willow family. Willows are widely known for their thin, drooping branches with narrow leaves. Black willows usually grow near rivers and ponds. Pussy willows are small, shrubby members of the family. Aspens, cotton-woods, and poplars are members with rounded leaves.

Walnut family. This family includes walnut, hickory, and pecan trees.

Walnut family. This family includes walnut, hickory, and pecan trees.

Laurel Family. This family includes the sassafras, a common tree throughout most of the eastern United States. Its range extends south into Florida and parts of Texas, and north to Michigan and southern Maine. Historically (about 100 years ago) sassafras wood was sometimes used to make furniture and fence posts in the southern states.

Laurel Family. This family includes the sassafras, a common tree throughout most of the eastern United States. Its range extends south into Florida and parts of Texas, and north to Michigan and southern Maine. Historically (about 100 years ago) sassafras wood was sometimes used to make furniture and fence posts in the southern states.

Birch family. Several species of birch are found across North America. Most are trees, but two species in the northern United States, in Canada, and the Arctic are very small. These dwarf birches grow close to the ground, reaching a height of only three feet. Remember: tree families are really plant families that include trees—and many members of a family might be shrubs and small plants.

Birch family. Several species of birch are found across North America. Most are trees, but two species in the northern United States, in Canada, and the Arctic are very small. These dwarf birches grow close to the ground, reaching a height of only three feet. Remember: tree families are really plant families that include trees—and many members of a family might be shrubs and small plants.

Several species of palm trees grow in the southeast United States and in California. A young Florida royal palm like this one could grow to a height of about 80 feet.

A group of sassafras trees in fall color.

Beech family. Beech trees produce seeds that are eaten by deer, chipmunks, grouse, turkeys, and many other species of birds.

Beech family. Beech trees produce seeds that are eaten by deer, chipmunks, grouse, turkeys, and many other species of birds.

Elm family. Elm trees are known for their spreading fountain shape or vase shape. The leaves of the American elm have a toothed edge, parallel veins, and a rough surface.

Elm family. Elm trees are known for their spreading fountain shape or vase shape. The leaves of the American elm have a toothed edge, parallel veins, and a rough surface.

Oak family. Famous and familiar for their acorns, there are more than 30 different oak tree species found in North America. Many more are shrubs.

Oak family. Famous and familiar for their acorns, there are more than 30 different oak tree species found in North America. Many more are shrubs.

Magnolia family. Magnolia trees are native to the southern United States but have been successfully planted and grown as far north as Maine. The tulip tree is also a member of the magnolia family. A large forest tree throughout many of the eastern states, it is found as far south as Florida. The normal range also extends north to Connecticut and Massachusetts.

Magnolia family. Magnolia trees are native to the southern United States but have been successfully planted and grown as far north as Maine. The tulip tree is also a member of the magnolia family. A large forest tree throughout many of the eastern states, it is found as far south as Florida. The normal range also extends north to Connecticut and Massachusetts.

Rose family. Roses? Yes, this plant family includes small plants like garden roses—and also strawberries and raspberries! Several trees are members of the rose family, too: apple, plum, black cherry, chokecherry, almond, and crab apple trees. Hawthorns are also included, with more than 100 species in North America.

Rose family. Roses? Yes, this plant family includes small plants like garden roses—and also strawberries and raspberries! Several trees are members of the rose family, too: apple, plum, black cherry, chokecherry, almond, and crab apple trees. Hawthorns are also included, with more than 100 species in North America.

Maple family. In North America, there are more than a dozen species of maple trees. There are also many species that are shrubs. And more are found in Great Britain, Europe, and China, with a total of more than 100 species worldwide.

Maple family. In North America, there are more than a dozen species of maple trees. There are also many species that are shrubs. And more are found in Great Britain, Europe, and China, with a total of more than 100 species worldwide.

Horse chestnut family. In North America, this includes buckeye trees. The horse chestnut is often planted as a shade tree and for its beautiful flowers. It is a native of Europe.

Horse chestnut family. In North America, this includes buckeye trees. The horse chestnut is often planted as a shade tree and for its beautiful flowers. It is a native of Europe.

The leaves of four different species of maples. The first is a red maple, the second is a sugar maple, and the third is a silver maple. The last, a box elder maple, has a leaf divided into three leaflets.

The large cuplike flowers of the tulip tree are nearly two inches across.

Linden family. Also called basswood, this family is known for its sweet-smelling flowers. In England and Europe, lindens are called lime trees, but they are not related to the lemon or lime trees that produce citrus fruit.

Linden family. Also called basswood, this family is known for its sweet-smelling flowers. In England and Europe, lindens are called lime trees, but they are not related to the lemon or lime trees that produce citrus fruit.

Cactus family. A cactus doesn’t look at all like the other trees listed here, but the large saguaro cactus of the desert Southwest can grow 40 to 50 feet tall. Old saguaros branch out into several upward-reaching “arms.” Most cactus species are much smaller plants.

Cactus family. A cactus doesn’t look at all like the other trees listed here, but the large saguaro cactus of the desert Southwest can grow 40 to 50 feet tall. Old saguaros branch out into several upward-reaching “arms.” Most cactus species are much smaller plants.

Dogwood family. The flowering dogwood of the eastern states grows about 30 to 40 feet tall. It has been raised and cultivated as a landscaping tree and is commonly planted near homes and even along highways. There are smaller species of shrub-sized dogwoods—and even a woodland wildflower!

Dogwood family. The flowering dogwood of the eastern states grows about 30 to 40 feet tall. It has been raised and cultivated as a landscaping tree and is commonly planted near homes and even along highways. There are smaller species of shrub-sized dogwoods—and even a woodland wildflower!

Tupelo family. There are just a few species in the southeastern United States.

Tupelo family. There are just a few species in the southeastern United States.

Heath family. Rhododendrons and mountain laurels belong to the heath family. Many different cultivated varieties are raised as landscaping shrubs. The heath family also includes blueberry plants and woodland wildflowers such as trailing arbutus and wintergreen.

Heath family. Rhododendrons and mountain laurels belong to the heath family. Many different cultivated varieties are raised as landscaping shrubs. The heath family also includes blueberry plants and woodland wildflowers such as trailing arbutus and wintergreen.

The flowering dogwood tree of the eastern United States has large white petals that are called bracts. Though they are not true petals, they are quite beautiful.

These wildflowers (called dwarf cornel or bunchberry) are members of the dogwood family, along with flowering dogwood trees. The flower stalks are only about six inches tall.

Olive family. The olives you eat are part of this family, along with many different species of ash trees. Lilac and forsythia shrubs are also members.

Olive family. The olives you eat are part of this family, along with many different species of ash trees. Lilac and forsythia shrubs are also members.

More families! There are many other plant families that include trees. The myrtle family includes the eucalyptus trees (gum trees) of Australia. There are about 500 species of eucalyptus in Australia. Although they are native to that country, many are planted in California and Florida.

More families! There are many other plant families that include trees. The myrtle family includes the eucalyptus trees (gum trees) of Australia. There are about 500 species of eucalyptus in Australia. Although they are native to that country, many are planted in California and Florida.

The legume family includes small plants like peas and clover, but also acacia trees, found in Hawaii and Florida, Australia, and Africa. The holly family includes the evergreen American holly tree and several shrubs.

Trees that have green leaves on them all year, such as pines, spruces, and hemlocks, are usually called evergreens by gardeners and nursery growers. These trees lose some of their needles in the autumn, but they are replaced by new ones. The trees still look green all year because they have lost only some of their needles. Evergreen trees like pine and spruce produce woody cones that contain seeds, so botanists called them conifers. A forest of conifers is called a coniferous forest. (A few trees from other families might remain evergreen all year, such as the American holly—but it’s not a conifer.)

Trees that lose all their leaves every autumn are often called broadleaf trees, because their leaves are flat and wide. Botanists and naturalists usually call them deciduous (dee-SID-yuu-us) trees. The leaves of most deciduous trees turn yellow, red, or orange in the autumn, before they all fall off.

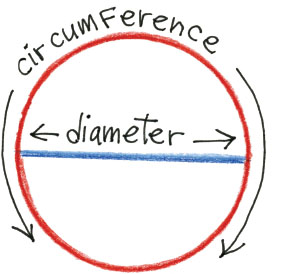

“Champion-sized” tree species are measured by circumference (the distance around). But trees cut for lumber and firewood are usually measured by diameter (the distance across).

The trunk of this pitch pine is 43 inches in circumference. Notice the thick, rough bark. The largest and oldest pitch pines can have a circumference of 60 to 100 inches.

Naturalists measure the circumference (as well as the height) of a tree to find out what is the largest (and sometimes oldest) tree in an area. You can easily measure the circumference of a tree trunk yourself.

MATERIALS

Tape measure (the flexible tape measure used for sewing is best)

Tape measure (the flexible tape measure used for sewing is best)

A tree you can walk right up to

A tree you can walk right up to

A friend/helper

A friend/helper

1. Have a friend hold the measuring tape in place, about 4 feet from the ground—unless you can get your arms around the tree by yourself!

2. Bring the length of measuring tape all the way around the trunk to the beginning.

3. Read the measurement in feet or inches on the tape. Now you know the circumference of that tree!

4. Find a much smaller tree or a larger tree, so you can compare sizes. After you have measured a few different trees, you will be able to estimate the circumference of other trees that have a similar size.

Hint: If you keep your tape measure in your pocket, you can measure the circumference of a tree any time!

Many of the trees in the families described here can grow very tall and have very big trunks. You can measure the circumference (sir-KUM-fer-ens) of a tree’s trunk to find out just how big it is. Circumference is the measurement all around the trunk, about four feet from the ground.

You have already noticed the different shapes that leaves can have. There are even more patterns and designs to notice in the veins of leaves. The leaf of an American chestnut has a central vein (the midrib) that runs from the petiole to the tip, with parallel (side-by-side) veins spreading out from it. The veins on a red maple leaf don’t have a central midrib. Instead, the veins spread out right from the petiole. The veins of a flowering dogwood leaf grow away from the midrib in graceful, curving arcs.

Sometimes it’s easier to see the veins on a leaf if you turn it over and look at the underside. You might notice that the underside of a leaf is lighter in color than the top. Silver maples are known for the silvery-green undersides of their leaves.

Three different patterns of leaf veins: the straight, parallel (side-by-side) veins on an American chestnut; the branching veins of a white oak leaf that go out to the tips of the lobes; and the curving veins of a flowering dogwood.

The shapes of leaves and the arrangement of their veins make interesting patterns and designs. You can use some of your pressed leaves to show these designs in an artistic way.

MATERIALS

Pressed leaves (see the “Press Leaves to Preserve Them” activity on page 9)—smaller sizes are best to try first

Pressed leaves (see the “Press Leaves to Preserve Them” activity on page 9)—smaller sizes are best to try first

A small notebook—or two!

A small notebook—or two!

Roll of clear packing tape or mailing tape (about 2 inches wide)

Roll of clear packing tape or mailing tape (about 2 inches wide)

Crayons or colored markers

Crayons or colored markers

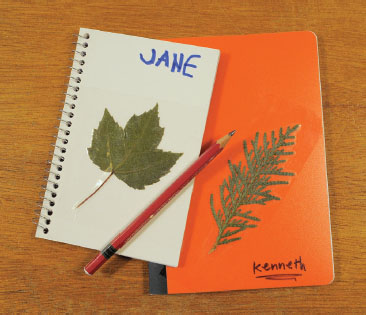

1. Place an interesting leaf on the cover of your notebook. It’s easier if you put it right in the center.

2. Cut a piece of plastic tape long enough to cover the leaf completely. Carefully press the tape over the leaf. Start with the petiole and press toward the tip. You may have to hold down the leaf with one hand.

3. Once the tape is in place, rub and press the tape over and around the leaf evenly. You might need two pieces of tape. Now you have a preserved, permanent specimen right on your notebook! You can also use crayons or markers to decorate the notebook with a colorful border, or write your name or the name of the tree on the front.

A red maple leaf was used to decorate Jane’s notebook, and a small twig from an arborvitae (northern white cedar) is on Kenneth’s notebook.

Bigtooth aspen, quaking aspen (also called trembling aspen), and cottonwoods are often known by the common name poplars or popples. Here are some other common names of trees:

A sugar maple is often called a rock maple.

A sugar maple is often called a rock maple.

Northern white cedar is called arborvitae by gardeners and landscapers.

Northern white cedar is called arborvitae by gardeners and landscapers.

Longleaf pine is also known as southern pine or yellow pine.

Longleaf pine is also known as southern pine or yellow pine.

American basswood is also called a linden tree. In England and Europe, basswoods are called lime trees—even though they are not related to lemon and lime citrus trees.

American basswood is also called a linden tree. In England and Europe, basswoods are called lime trees—even though they are not related to lemon and lime citrus trees.

Larch trees are also known as tamaracks and hackmatacks. But in California, the lodgepole pine is sometimes called a tamarack.

Larch trees are also known as tamaracks and hackmatacks. But in California, the lodgepole pine is sometimes called a tamarack.

Black tupelo may be called black gum or sour gum in the southern states. In New England, it is often called a pepperidge tree.

Black tupelo may be called black gum or sour gum in the southern states. In New England, it is often called a pepperidge tree.

The leaves of a black tupelo, also called a pepperidge tree, turn deep red-orange in the fall.

A white pine tree has different bark on its trunk than a black cherry tree. And a sycamore tree has very different bark than a red maple. The color, texture, and patterns on bark are different for most tree species. Bark is the tough outer covering for trees. It protects the inner part of the tree, which may still be growing. It also protects the living inner parts from storm damage or insects.

The shagbark hickory is named for the long strips of shaggy bark that hang away from the trunk.

The white birch, also called paper birch, has white bark that often peels away in thin, papery pieces. White birch trees are found across the northern United States to Alaska, and across much of Canada.

Even if you can’t identify a single tree in your neighborhood, take a look at the bark on the tree trunks as you walk by. You likely will see different types of bark: smooth bark, rough bark, and even bark that has a sort of pattern. You will soon develop an eye for noticing these details on other trees.

Bark has been used by Native American tribes to make small boxes and trays, birch-bark canoes, and roofs for small houses and lodges.

The answer is: a lot! More than 600 species of trees are native to North America. Hundreds more are non-natives—they are wild and native in other parts of world, but are raised and planted here. Eucalyptus trees are native to Australia, but they are grown and planted in California and Florida. Norway maple trees are wild and native to Scandinavia and Europe, but have been planted successfully as non-natives in North America.

Some botanists estimate that there are more than 1,000 species of shrubs and trees, both native and non-native, just in North America. Thousands more species grow in South America, Asia, Europe, Africa, and India, especially in tropical climates. Some researchers estimate that there could be 100,000 different species of trees and shrubs around the world!

The trunk of a tree may be visited by insects and spiders looking for food or a place to lay eggs. A woodpecker might land on the trunk looking for those insects. There may be moss or lichens (LIKE-ins) growing on the bark. If you take a close look at a tree’s bark, there might be a lot to see!

MATERIALS

An area where you can look closely at a tree’s bark

An area where you can look closely at a tree’s bark

Your sharp eyes

Your sharp eyes

Magnifying glass

Magnifying glass

1. Walk up to a tree and look at its bark. A quick look will tell you if there are holes made by wood-boring beetles or maybe by a woodpecker.

2. Look for moss or lichens. Moss usually looks green and soft. But lichens can look frilly or lacy, and many are gray-green. Lichens are very interesting to look at because of their shape and texture.

3. Use a magnifying glass to investigate the surface of the bark more closely. If the bark looks rough with deep cracks, there might be tiny insects crawling in it. You might see a small group of wingless “bark lice,” or psocids (SO-sids), which feed on tiny bits of fungi and algae.

You might also find a moth resting on the bark, especially if the tree is near a light that was left on the night before. Looking closely at bark, lichens, and moss can reveal a world of life that most people never see.

Lichens often look lacy or frilly and grow in circular “medallions” on tree bark.

A ladybug rests on a tree trunk.