Spurning the idea of going into local digs in Worthing, I opted to drive home to Bexley every night after the show. Back then, though there weren’t any motorways, the roads were empty and I was back in no time. It was a happy few weeks travelling to and fro. I didn’t know it but it was to be my last stage appearance for many decades–but perhaps the critics did?

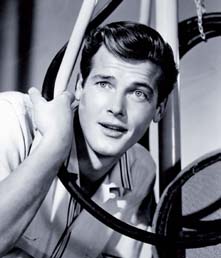

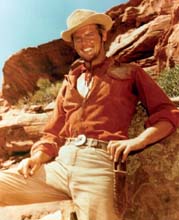

Towards the end of 1956, my knight in shining armour, Ivanhoe, came along. There were pros and cons to taking on this role. The main pro was that it was to be a long-running series and a guaranteed year’s work, with a holiday. The main con was that it was TV, rather than my preferred choice of a movie. However, bearing in mind what Coward had told me about not being an actor if I wasn’t working, I accepted. There was a great deal of snobbery about being a film actor versus a television actor, but it was only when I was halfway through the series that I really started to worry about being typecast as a TV actor, and feared that I’d never work in film again. There was a great stigma in being branded a ‘TV actor’ in Britain back then, and whilst many crossed from film to TV, rarely did anyone go the other way.

We filmed a pilot for Ivanhoe at ABPC Elstree. We shot in colour, during November. I started smelling a rat there and then. They had an extra shouting a line down from the cardboard battlements, which was supposed to be, ‘Lower the drawbridge for Sir Ivanhoe of Rutherwood!’ and all he could get out was, ‘Lower the bridge for Sir Robin of Ivanhood.’ There were ten takes of various combinations, bar the correct one. No expense was lavished on talent. Was this my biggest mistake?

When it came to location work for this half-hour epic, there were no leaves on the trees in Sherwood Forest, so we upped and moved to California and shot out in the valley, and in their Sherwood Forest. Very extravagant, I thought, for a thirty-minute pilot. Perhaps things aren’t so bad after all.

There wasn’t any colour in television in 1956, and so when the decision was made to go to the series, we filmed in black and white–which was undoubtedly much less expensive and undoubtedly also why the show was never repeated in later years.

I had a couple of friends in LA whom I got on the show, one being an Irishman named Keith McConnell. When he was brought in for the reading he was asked if he could ride a horse. He replied, ‘I’m Irish’, which they took to mean he could ride like Gordon Richards.

It came to the scene where Ivanhoe is riding back home and is stopped by some soldiers. As they approached, with lances and swords drawn, the director David MacDonald said, ‘OK, mount up, Keith.’

‘I’m not getting up on that focking thing!’ came the reply. Eventually, a small band of prop boys and assistants got Keith up on the horse, where he sat, rigid. ‘I’m not focking moving on this focking thing,’ he warned.

Then, when it was time to go for the take, a rather flustered Keith, instead of delivering his very English line of ‘Sir Ivanhoe of Rutherwood, Sir Maurice of Beresford would speak with you,’ said, in a very thick Irish accent, ‘Ah, Sir Ivanhoe, Sir Maurice would have words wid yas.’

The other friend I got on the show was Tony Dawson, most famous for his role in Dial M for Murder and the first Bond movie. He was rather like George Sanders in that he could fall asleep at the drop of a hat. After one take, in which he was wearing full tabard, he decided to lie down in the long grass and dropped off to sleep. Nobody noticed him, and the unit moved on to another location in the forest. The next thing he knew, he was surrounded by children asking, ‘Is he dead?’ If you’d come across an ancient knight, in full armour, lying in a field, what would you think?

Robert Brown, who played Gurth, became a very close friend and we worked together on a number of things later, including a few Bond films. He was a bugger in that he was a giggler. In one episode, there was a master shot starting with Ivanhoe addressing a group of knights around a table; then a door in the background opens and the camera moves around over me, and Bob Brown–Gurth–walks up to me and the camera, which is pointing over my shoulder at him, and says:

‘Sir Ivanhoe, Prince John has landed his forces at Runnymede.’

To which I had to reply with one of those awful bloody lines, ‘Gurth, saddle up my horse. We must ride forth to meet him.’

When I started saying, ‘Saddle up my horse,’ Bob began smirking. The smirk became a laugh.

‘Cut!’ shouted Bernie Knowles, the director. ‘We’ll go again.’

Take two. We go through the scene again, and when I get to the said line, this time I burst out laughing.

After take eleven, Bernie was getting a little fed up. ‘Right, we’ll all sit down and have a nice cup of tea,’ he suggested in his Yorkshire drawl, ‘and then go back when we’re all settled down.’ A cup of tea, of course, was going to be the solution to all our problems.

After about fifteen minutes, we returned to the set. ‘Have you all settled down then?’ Bernie asked. ‘Right, OK, we’ll go again.’

‘OK. Mark it.’

The clapperboard clapped.

‘Right. And…Anxious!…Erm–no, I mean action!’ We all fell about this time. The scene, such a simple one, was doomed and we didn’t complete it until the next day.

I fell into a fairly quiet routine. Production was based at Beaconsfield. Throughout the week, I lived at the Crown Inn in Penn. I’d get up early and, trying not to disturb anyone, I’d go downstairs, make a light breakfast, then drive to the studio in my Ford Zodiac. In the evening, I’d eat either at the Crown or at one of the other local pubs. Then, at weekends, it was back to Bexley to spend time with family and friends. On Sundays Dot would often invite lots of friends for lunch–many of the characters she’d been working with in variety.

When we were shooting Ivanhoe, a suspected duodenal ulcer forced me to take a break. It was 1957, and Dot and I took off for a couple of weeks to Torremolinos–I don’t think there was more than one hotel there then. It was a truly idyllic spot…When Dot came back to England she wrote a song called ‘Torremolinos’ and all of a sudden everyone had heard of it. I mastered the Spanish language on that trip, two weeks of Berlitz Spanish, Yo soy muy contento, dos huevos por favor… what a linguist.

Schedules were tight on Ivanhoe. We only had five days to shoot an entire episode. They would be long days as each episode would feature three fights, lots of physical stuff and sword-fighting. Guest stars were often cast, usually in sinister roles, and would invariably say things like, ‘I’ve done sword-fighting at Stratford and won’t need a double.’ My stunt double, Les Crawford, and I would run through a couple of quick routines, and when the actors saw how fast we were, they’d invariably say, ‘Oh, OK, best have a double after all.’

We had one stuntman, Fred Haggerty, who worked all through the series. We knew him as ‘Free Frust Fred’, because in rehearsing sword-fighting routines he would say, ‘One, en garde. Two, parry. Three, thrust!’ Only, being a cockney, it came out, ‘Free, frust!’

One day, out of the blue, I received a call from Lana Turner. She was in England making a film called Another Time, Another Place. One of her co-stars was a young, handsome Scottish actor by the name of Sean Connery. I often wonder what became of him…Lana said that she had rented a house on Bishop’s Avenue, a rather swanky thoroughfare in North London. As a matter of fact, I already knew the house as it belonged to one of the Bernard Brothers, a very successful variety act, they were mime artistes and friends of Squires. Anyhow, Lana declared that she going to throw a party, and I was invited.

As the guests arrived, Lana pinned a label on them, mine read ‘Roger Boy Knight’, in reference to Ivanhoe of course. One of the other guests was a rather swarthy individual who carried the label Johnny Dago. I actually saw very little of him during the evening, which progressed from drinks to food to more drinks and music to dance…

At some point, as the guests started to thin out, Lana asked me to dance–not one of my talents I must admit. As I shuffled around the floor with her in my arms, probably standing on her toes several times, I felt a cold breeze on the back of my neck. I glanced over my shoulder to find ‘Johnny Dago’ leaning against the doorjamb and staring, unsmilingly, at Lana and me.

A little voice in my head said, ‘Roger it is time you went home!’ I didn’t need a second prompt. I excused myself and made for the door.

A few weeks later I read that ‘Johnny Dago’–better known as gangster Johnny Stampanato, with whom Lana was romantically involved, having recently divorced Lex Barker–had been deported by Scotland Yard for having physically abused Lana, and for having entered the UK illegally using a passport in the name of John Steele. He had, I read further, also turned up on the set of Lana’s film and threatened Sean Connery with a gun. Sean wrestled the gun from him and decked him with a right hook; all very Bondian. Johnny was convinced that Sean was having an affair with Lana, also very Bondian.

A few months later we were all shocked, but not surprised, to learn that Stampanato had been stabbed to death; allegedly by Cheryl Crane, Lana’s teenage daughter, after a huge fight at Lana’s Beverly Hills home.

When he had first arrived in California, Stampanato worked for Micky Cohen, one of the West Coast’s most notorious gangsters. I once met Cohen at a nightclub where I had gone to see the great Don Rickles, a fantastic comedian who became known as the ‘master of the insult’. Gary Cooper was also there that night, and Rickles, having made a few cracks at Cooper and then dismissing me for being a pretty boy at Warner Brothers, turned his attention to Cohen. He called him a dirty hood, then–obviously thinking better of it–dropped on his knees and held his hands together in prayer towards the gangster, saying that he was only joking and he loved MISTER Cohen SIR!

There were very few parts for women on Ivanhoe. Adrienne Corri was in one episode and I remember Jimmy Harvey, the cameraman, was obviously becoming a little frustrated with her. At one point she was sitting looking in the filter of the lens at her reflection. ‘Oh, Jimmy, I have a double shadow here.’

‘If you point your nose in the direction it should be pointing in,’ he snapped, ‘you’ll only have one bloody shadow!’

On another occasion, our American producer from Columbia came over with a young would-be starlet with rather large mammary glands to be in an episode. The director tried to point out to our boss–who had a reputation for chasing any would-be starlet around the office–that there wasn’t a part.

We were told to ‘feature’ this girl. OK. Well, in every scene her breasts framed either the left- or right-hand side of the screen. She never said a word, just appeared in profile with her 38D cups. As the floor had sand, straw and cork all over it, it was impossible to put chalk marks down for my toe to hit–so I’d know how far I should be from the lens. They therefore laid a baton for me instead, and this girl, who didn’t have a word of dialogue, after a few days asked, ‘Why can’t I have one?’

The whole crew would have liked to have given her one…but anyway, they produced this baton in the shape of mammaries and put them down for her. I remember her saying, ‘Do I put my toes in here?’ One of the crew, in the rafters, shouted, ‘No, love, your tits.’

As I’ve mentioned, we had quite a few guest stars on the show. Christopher Lee was cast as Otto the Hun in one episode. Lance Comfort was directing. We’d been on location for days and days; the weather was just awful. I was supposed to fight a duel with Otto to win the freedom of a serf–some thirteen- or fourteen-year-old child actor. Christopher was standing there waiting for the clouds to clear, and he came out with, ‘Will dieses verfluchte Wetter, das überhaupt frei ist, ist es nicht genug gut,’ or words to that effect.

The kid looked at him, star-struck, and said, ‘Cor, do you speak German?’

Without pausing for breath, Christopher said, ‘Yes, and Portuguese, French, Italian, three dialects of Urdu, Swahili…’ He went on and on–and yes, he does speak all these languages.

Finally, word came through from Wardour Street that we couldn’t waste any more time and had to shoot regardless. It was drizzling and Lance said, ‘Right, we’re going to shoot.’

With that, Johnny Briggs, my dresser, came running forward and in a very camp voice said, ‘Oh Mister Comfort! Mister Comfort! You can’t shoot now!’

‘Why not?’ asked Lance.

‘Because Roger’s armour will get rusty!’ said Johnny with a hand on his hip.

I worked with Johnny many times and he never failed to come out with some wonderful lines. On another occasion, a bunch of the stunt boys were sitting around in the wardrobe department and Johnny was sewing on buttons for someone. One of the boys read out the newspaper horoscopes and called, ‘What’s your birth sign, Johnny?’

‘Hairy-arse, of course,’ came the reply.

After a day of being buffered around on horses, being thrown into mud and so on, I’d get out of my costume and have a bath. Johnny would come in with a warm towel to put around me. There he’d stand, and murmur, ‘Hmmm, not a bottom like my Hardy’s.’ He was referring to Hardy Kruger, the year before, on a film called The One That Got Away. I actually told Hardy that story years later when we were making The Wild Geese. He did have a nicer bum than me.

Oh, another Johnny Briggs story! I was having a cup of coffee in my dressing room one morning and we had a new assistant director who tapped on the door, opened it and said, ‘They want you on the set, Roger.’

He was almost out of the door, when Johnny said, ‘Call boy! Call boy, come back here!’ The boy came back, and Johnny addressed him.

‘When you come to a fillum star’s dressing room you knock and wait to be bid enter. When you are bid enter you come in and say “Sir, when you are ready, sir, they are ready for you on set, sir.” And then you exit.’

For three months the boy thought Johnny was the producer.

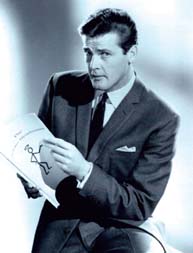

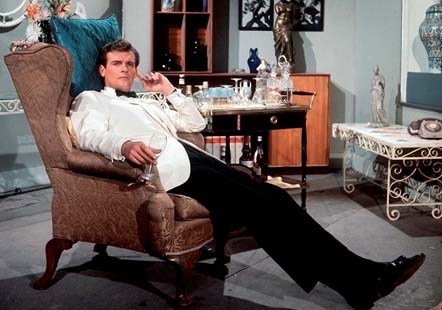

As the series drew to an end, I was worried about finding work as a television actor. It was my father who suggested I try and do my own thing, and he mentioned either John Creasey’s series of adventure novels featuring the Hon. Richard Rollinson, The Toff, or Leslie Charteris’s The Saint as being suitable for possible TV series. I liked the idea of The Saint, having seen the George Sanders movies, and so I made a half-hearted attempt at acquiring the rights. At that stage, author Leslie Charteris wasn’t interested–in either me, or the idea of television, or perhaps both? I drew a blank.

Fortunately, a couple of jobs came up in the USA. Though, yes, they were TV and not film. Still, remember what Uncle Noël said. The first was an episode of The Third Man with Michael Rennie. Michael was about four inches taller than me, and of course he was the hero, which presumably meant I was a not-so-nice guy. In one scene he had to grab me by my sweater and pull me towards him, and so I made a point of wearing a loose-fitting sweater. But in every take, he would grab my rather well-developed pectorals. On the fifth take I let him have it in the shin with my boot. See how you like it, I said to myself.

Another British actor, Max Adrian, also in my episode, came in one day looking rather tired. He said he hadn’t been sleeping at all well. ‘Ah,’ I said. ‘Guilty conscience?’

He nodded.

‘For things you’ve done?’ I asked.

‘No,’ he replied, ‘for things I haven’t done. There were times when I could have called my mother, and didn’t. Now it’s too late. She’s passed away.’

Hit suddenly by a combination of emotion, homesickness and maybe even guilt, I had to stop what I was doing, find a phone and call my parents. It was so good to hear their cheery hello on the other end of the line. From that day on, I always made a point of calling them whenever I could during my career and travels. I very much miss not being able to do it any more.

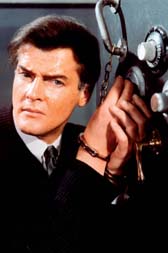

Alfred Hitchcock Presents was the second job out there. The series was topped and tailed by a speech from the great man himself, but of course he was never around the set. My episode was The Avon Emeralds with Hazel Court as my co-star. I don’t think it was particularly memorable, but it did keep me in LA and in the thick of where it was all happening. I wondered if I might ever make a return to movies. Soon after that the phone rang. It was my agent. Could I report to Warner Brothers for a meeting? he asked. It seemed a contract was in the offing, along with–a movie…