As a contiguous land area that has been home to most of humanity, Eurasia has long enjoyed the benefits of scale, long-distance trade, and the innovation and diffusion of technologies. For at least five thousand years, the horse has played a key, even decisive, role in Eurasia’s development, offering unequalled transport services, horse power for agriculture, powerful military capacity, rapid communications, and the capacity to govern large areas in a unified state. This is why the domestication of the horse some fifty-five hundred years ago gave rise to the first empires of Eurasia, and also why I have chosen the Equestrian Age as the name of the third age of globalization.

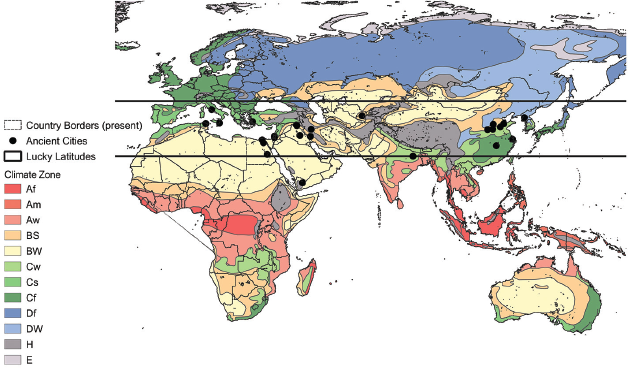

Our examination of this age of globalization begins with the band of grasslands just to the north of the lucky latitudes known as the steppes of Asia (figure 4.1). These great grasslands include the western Eurasian steppes, spanning the northern Black Sea coast, the Caucasus Mountains, today’s Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, and the eastern Eurasian steppes, notably Mongolia and northern China, including Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and parts of northeast China. The steppes, classified as climate zone BS, are semiarid but not desert. This climate zone accounts for around 10.8 percent of the land area of Eurasia, and was home to a somewhat larger proportion of the population, around 15.1 percent in 3000 BCE and 14.5 percent in 1000 BCE.

4.1 Eurasian Steppe Region

The steppes provided the abundant energy input—grass—and the hospitable climate for the most important transport vehicle for almost all of human history: the horse. The steppes also served as the great long-distance highways connecting Eurasia well before paved roads. Horse-driven transport was, in effect, the automobile, truck, railroad, and tank of the ancient empires. It was the only available high-speed option for land-based movements of traders, messengers, warriors, and explorers.

To understand the significance of the horse’s arrival in human history, let us start with animal domestication more generally. Animal domestication was a long and complex process, starting in the Paleolithic Age with the domestication of the dog (around fifteen thousand years ago in China) and continuing in the Neolithic Age over many thousands of years. The archeological evidence suggests that the ruminants (goats, sheep, and cattle) were originally domesticated during the period from 10,000 to 8000 BCE in southwest Asia. The donkey was domesticated (from the African wild ass) in Egypt around 5000 BCE. Dromedary camels were domesticated in Arabia around 4000 BCE, and camelids (alpaca and llama) in the high Andes around the same time. Horses were domesticated late in the Neolithic, around 3500 BCE, in the western Eurasian steppes, the region spanning the north coast of the Black Sea, the northern Caucasus, and western Kazakhstan.1

Here is a staggering reality: The domestication of animals occurred almost exclusively in Eurasia and North Africa (in the case of the donkey). No large farm animals were originally domesticated in tropical Africa. Africa’s own ungulates, including antelope and zebras, resisted domestication. Domesticated sheep and goats arrived to Africa from Southeast Asia, horses from the western Eurasian steppes, cattle from Southwest Asia, the dromedary from the Arabian Peninsula, and the donkey from North Africa.

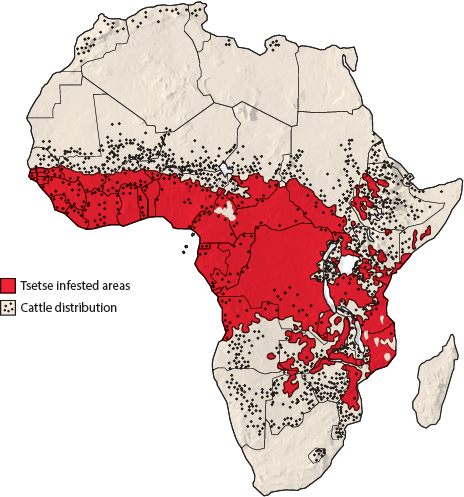

In general, the African tropical environment proved extremely harsh for many farm animals. Cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, horses, and donkeys were vulnerable to trypanosomiasis within the vast tsetse belt of West and Central Africa (figure 4.2) and to other diseases such as the tick-borne east coast fever, caused by the protozoan pathogen Theileria parva, equine piroplasmosis, also transmitted by ticks, and African horse sickness, an orbivirus transmitted by insect vectors. Many domesticated animals did successfully adapt to the tropical African environment, at least in some places, and many African regions have had mixed crop-and-animal farm systems for thousands of years. Nonetheless, much of tropical Africa long suffered from the scarcity of horses, donkeys, and other pack and draft animals.2

4.2 Tsetse-Infested Areas of Africa

Source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1998, G. Uilenberg, A field guide for The Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention of African Animal Trypanosomosis, www.fao.org/3/X0413E/X0413E00.htm#TOC. Reproduced with permission.

The situation in the Americas was even more dramatic. Most domesticated animals reached the New World only upon the Columbian exchange of flora and fauna between the Old World and New World after 1492, when the Old World farm animals arrived with European conquerors. The hunter-gatherers of North America killed off the wild horse (Equus occidentalis) and other megafauna, including the woolly mammoth, and saber-toothed cat.3 The only surviving candidates for domestication were the two camelid species of the high Andes (the llama and the alpaca), two birds (the turkey and the Muscovy duck), and the guinea pig. Other than llamas and alpacas in the high Andes, the Amerindian populations had to make do for more than ten thousand years with no large domesticated animals for pack and draft work and without horses for long-distance transport and communications. The early extinction of the horse in North America was therefore a loss to the Amerindian civilizations of catastrophic dimension. The next time that Amerindians encountered the horse was when the Spanish conquistadores showed up on horseback at the end of the fifteenth century.

The horse is unmatched in its importance for economic development and globalization. Only the horse offered the speed, durability, power, and intelligence to enable deep breakthroughs in every sector of the economy: farming, animal husbandry, mining, manufacturing, transport, communications, warfare, and governance. Regions of the world that lacked horsepower fell far behind those that had it, and typically ended up being conquered by warriors on horseback. That ancient story was played out repeatedly in East Asia, South Asia, West Asia, Europe, Africa, and the Americas.

The horse is one of subgenera of the genus Equus, the others being the African ass, the Asian ass (onager), the Tibetan ass (kiang), and several subgenera of zebras. The native range of the horse, based on its distribution in the late Pleistocene, is shown in figure 4.3. In the late Pleistocene, the horse was native to most of the Americas and Eurasia other than South Asia, the Arabian Peninsula, and Southeast Asia. Horses were present in Africa only at the very northern tip of the continent, in the small temperate band north of the Sahara.

4.3 The Distribution of Wild Horses in the Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene

Source: Pernille Johansen Naundrup and Jens-Christian Svenning, “A Geographic Assessment of the Global Scope for Rewilding with Wild-Living Horses (Equus ferus),” PLoS ONE 10(7): https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132359

Figure 4.3 depicts the remarkable decline in the range of horses between the late Pleistocene (light) and the mid/late Holocene (dark). The main reason is that horses were hunted for meat in the early Holocene and driven to extinction throughout the Americas and in most of Eurasia other than the steppe region. The steppes, which were remote from the more populous concentrations of hunter-gatherers and early farmers, offered a refuge for the wild horse. It was therefore from the steppes that the horse would reemerge as the key technology for war and empire some eight thousand years after the start of the Neolithic period.

Of the other subgenera of the genus Equus, only the African wild ass was domesticated. The Asian and Tibetan asses and the various subgenera of zebras all proved resistant to domestication. The native range of the African wild ass was the drylands and deserts of North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Its domestication appears to have originated around 5000 BCE in Nubia, today’s southern Egypt, perhaps 1,500 years before the domestication of the horse.

While cattle served as slow-moving beasts of burden (draft animals), donkeys served mainly as pack animals, carrying heavy loads. A recent study of early donkey domestication explains their pivotal role this way:

Donkeys are tough desert-adapted animals, and their ability to carry heavy loads through arid lands enabled pastoralists to move farther and more frequently and to transport their households with their herds. Domestication of the donkey also allowed large-scale food redistribution in the nascent Egyptian state and expanded overland trade in Africa and western Asia.4

The domestication of the wild horse (Equus ferus) followed that of the donkey around 3500 BCE. Domestication occurred as farmer-herders pushed north from Mesopotamia into the western Eurasian steppes. There they encountered the surviving feral horses. The horse was clearly not easy to domesticate, and the process took a considerable amount of time. The horse is fast and aggressive and ready to attack if cornered. It was probably first cornered, trapped, and subdued in group hunts. The initial purpose of domestication seems to have been to use the horse as a pack animal to carry loads across the grasslands. What ensued was several millennia of gradual technological developments and adaptations for the effective use of horses, including the gradual improvement of halters to harness loads, saddles, stirrups, types of carts and chariots, and weapons that could be deployed by riders in combat. The sites shown in figure 4.4 are the steppe regions with early horse domestication.5

4.4 Early Locations of Horse-Based Societies

Source: Pita Kelekna, The Horse in Human History, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

The result of horse domestication is an animal of remarkable versatility. It is a pack animal, able to transport goods long distances. It is a saddle animal, for use in warfare and farming (as in the herding of farm animals). It is a draft animal, able to pull wheeled vehicles. It has endurance, intelligence, and great speed. In short, it has played a decisive role in economic development.

Species of the camel family (Camelidae) have also played an important role in the more extreme climates of deserts and high plateaus. In the Old World, two species predominate: the one-humped dromedary of the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa, and the two-humped Bactrian camel of Central Asia, including Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, and Mongolia’s Gobi Desert. In the New World, two wild Andean camelids, the guanaco and vicuna, were domesticated to the llama and the alpaca, respectively. All of these species have played an important economic role, though to a lesser extent than the horse.

The Old World camels are distinctive for their ruggedness and ability to endure extreme temperatures, hot in the case of the dromedary and cold in the case of the Bactrian. Camels can go long periods, even weeks under certain circumstances, without drinking, and their humps store fat for long periods without food. Crucial as pack animals through deserts and high-steppe regions, they played an integrative role in long-distance trade as early as ancient pharaonic Egypt. The Old World camels were domesticated later than the horse, probably between 2000 and 1000 BCE.

The camel played multiple roles: as a source of milk and meat; as a pack animal in long-distance caravans across the Arabian Peninsula, the Egyptian desert west of the Nile, and later the Sahara Desert; as a battle animal; and as an animal for sport racing. The camel’s ability to carry heavy loads of up to five hundred pounds for fifteen to twenty miles per day over the course of a hundred days meant that camel transport across the Arabian Peninsula between Asia and the Mediterranean was competitive with travel by sea. The camel was also an important complement to the warhorse in Bedouin campaigns of raiding and conquest. Although camels could not stand up to horses in shock combat, they could powerfully aid the cavalry by carrying war supplies and water over large distances. One scholar summarizes the camel’s role in Mideastern nomadic societies as follows:

It seems clear the camel is the key without which there could have been no nomads in the hot deserts of the Old World. This one domestic animal provided food, transportation, and a basis for military power, and continued to do so under conditions no other animal of comparable capabilities could endure.6

The Andean camelids, the llama and the alpaca, were domesticated in the high Andes around 3000 BCE. The llama, the larger of the two species, served as a pack animal as well as a source of wool for coarse fabrics, milk, meat, and hides. The alpaca, smaller and with long, finer fibers, was used to produce fine fabrics, as well as for milk, meat, and hides. Recent research suggests that agriculturalists in the high Andes engaged in mixed-crop and animal-husbandry agriculture and that the llama served also as a vital pack animal for exchange between the highlands and the coastal lowlands of Peru. These camelids, the dog, and the guinea pig were the only domesticated animals available in the Andes.

Alongside the domestication of the horse, donkey, and camel, the advance from the Neolithic Age to the Equestrian Age occurred on other fronts as well. Most importantly, the New Stone Age gave way to the Metal Age, making possible new and stronger tools, weaponry, and artisanal products. The Copper Age commenced around 4000 BCE, though copper ornaments are known from earlier millennia. Copper is widely accessible in elemental form and can be melted at a relatively low temperature, 1085ºC. Smelting of copper ores requires a higher temperature, around 1200ºC. These temperatures are hotter than campfires and therefore required new methods of heating.

Copper is relatively soft in pure form; it becomes stronger and more durable as an alloy with tin, making brass, or with arsenic (though dangerous in the metalworking). The Bronze Age arrived with the discovery of the copper-tin alloy, beginning around 3300 BCE in the Near East, the Indus Valley, and the Yellow River valley. The problem with bronze was the scarcity of tin. There were few accessible tin deposits in the region of the Fertile Crescent. Tin mines were established in parts of Western Europe (Germany, Iberia), but the tin had to be transported long distances to the Near East. Other tin arrived from mines in Central Asia along the Silk Road.

Iron is superior to bronze in many ways, notably in strength per unit weight. Iron is also far more plentiful than tin. The problem with iron, however, is its very high melting point, around 1530ºC, almost 500ºC higher than copper. The vast amount of energy needed to melt iron ores drastically limited the large-scale production of iron products and delayed the onset of iron production. The Iron Age commenced around 1500 BCE, roughly 1,800 years after the start of the Bronze Age.

The extinction of the wild horse in the early Holocene meant that the Amerindians were bereft of horses until the arrival of the European conquerors. Nor did they have the benefit of the donkey, which originated in North Africa and did not arrive to the Americas until the Colombian exchange. The absence of equids certainly did not stop many remarkable advances of civilization in the Americas, but it did fundamentally alter, and limit, the civilizational advances that occurred. The Americas lacked the potential for long-distance overland transport, communications, agricultural productivity, and aspects of large-scale governance made possible by the horse and donkey. The llama served this purpose, but only to a limited extent, in connecting the high Andes with the lowlands of Peru.

The implications were profound, as cogently argued by the anthropologist Pita Kelekna in her magisterial account of The Horse in Human History. I summarize her conclusions in table 4.1, comparing long-term development in Eurasia and the Americas, the first benefiting from the horse and the latter bereft of the horse.

Table 4.1 Comparing Eurasia and the Americas

| Dimension of social life |

Americas (without the horse) |

Eurasia (with the horse) |

| Agriculture |

American steppes (prairies and pampas) remained most undeveloped and unpopulated |

Adoption of agriculture throughout the steppes, intensification in the temperate zones |

| Metallurgy |

Little transport of metals, very slow uptake and diffusion of metallurgy |

Long-distance transport of metals, more rapid diffusion of metallurgy |

| Trade |

Short-distance trade |

Long-distance trade, with horse-based trade encouraging other modes as well (e.g., canal building) |

| Diffusion of ideas and inventions |

Little diffusion of technologies such as writing, counting devices, arithmetic (e.g., role of zero) |

Extensive diffusion of technologies, including alphabets, arithmetic, use of the wheel |

| Warfare |

Small polities, governed as confederations |

Large empires, secured by horseback |

| Religion |

Little diffusion |

Long-distance diffusion |

| Language |

Little linguistic interaction |

Long-distance linguistic interaction |

Source: Data from Pita Kelekna, The Horse in Human History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009

Perhaps the first major horse-based society in Eurasia was the Yamnaya people, hypothesized to have emerged as an admixture of hunter-gatherers from the Caucasus and Eastern Europe. Their territory was the northern Caucasus between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea (known as the Pontic-Caspian Steppe). What is notable about the Yamnaya civilization, dated around 3500–2400 BCE, is their early domestication of the horse and their apparent remarkable success in migrating westward toward Europe. The Yamnaya civilization is closely linked in technologies and genetics to the so-called Corded Ware culture of northern Europe around 3000 BCE (named for the corded decoration of its pottery). Paleo-geneticists suggest that much of Europe’s population in fact reflects the admixture of two populations: the first originating with early farmers from Anatolia and the second with the Yamnaya people, itself an admixture of hunter-gatherer populations.7 The hypothesized dual origin of early Western European farm populations is illustrated in figure 4.5, showing two key migrations into Western Europe, the first from Anatolia dated around 7500–6000 BCE and the second from the steppes, dated around 4000–3000 BCE.

4.5 Rival Hypotheses: Neolithic Age Migrations from the Steppes and from Anatolia

Source: Wolfgang Haak, Iosif Lazaridis, Nick Patterson, Nadin Rohland, Swapan Mallick, Bastien Llamas, Guido Brandt, et al. “Massive Migration from the Steppe Is a Source for Indo-European Languages in Europe.” bioRxiv (2015): 013433. doi:10.1101/013433.

In support of the hypothesized migrations from the western steppes, archeologists point not only to the genetic record but also to the remarkable and rapid dissemination of major horse-related technologies—including the wheel, ox-driven carts, and depictions of horseback riding—through the vast area of Mesopotamia, Eastern Europe, northern Europe, and the Indus region. The domestication of the horse, with the unmatched mobility that it brought, enabled a dissemination of basic technologies over a huge area of Eurasia at a speed that was unprecedented in comparison with prior human experience.

One other fundamental cultural breakthrough apparently arrived with the Yamnaya and related peoples: Indo-European languages. As with the genetic code, the language code of western Eurasia and South Asia suggests a crucial admixture of languages from Anatolia and the western steppes, which together gave birth to the Indo-European languages, the family of almost all of today’s European languages (other than Basque, Estonian, Finnish, and Hungarian) and many of the languages of western Asia and northern India. Paleogeneticist David Reich offers a fascinating hypothesis based on the genetic record:

This suggests to me that the most likely location of the population that first spoke an Indo-European language was south of the Caucasus Mountains, perhaps in present-day Iran or Armenia, because ancient DNA from people who live there matches what we would expect for a source population both for the Yamnaya and for Ancient Anatolians.8

Reich also describes how the genetic record in India suggests that present-day Indians are an admixture of two ancestral populations, from northern India and southern India, with the northern Indian ancestral population genetically related to the populations of the Eurasian steppes, the Caucasus, and the Near East (Anatolia).

From the original domestication in the Pontic-Caspian steppes, the horse and horse-based civilizations spread throughout the temperate and steppe regions of Eurasia. The Eurasian steppes would remain regions of low population density in fierce, horse-based warrior societies. Their names would be dreaded among the sedentary societies of Eurasia, North Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, and East Asia for 3,500 years, from roughly 2000 BCE to 1500 CE. The first groups included the Hyksos, who conquered ancient Egypt around 1580 BCE and ruled for around 130 years, and the Scythians, who controlled parts of the ancient land routes between Asia and Europe from around 900 BCE to 400 CE. Later steppe conquerors include the Goths and Huns, between 400 and 600 CE; the Magyars and Bulgars, who settled Hungary and Bulgaria around 1000 CE; and the Seljuks and Mongols, who conquered vast territories of Asia from 1200 to 1400 CE.

The horse was also adopted by the far more populous agricultural societies after their early and often brutal encounters with the peoples of the steppes. The horse became a mainstay of farming, transport, and war for the early equestrian empires from Egypt to Mesopotamia, Persia, South Asia, and East Asia, and then later for the vast land empires of Alexander the Great, Rome, Persia, China, and India of the Classical Age of globalization. The land-based empires of the Classical Age would have been impossible but for the communications, transport, and military might of the horse.

The period from 3000 to 1000 BCE marked decisive civilizational advances in the Fertile Crescent, including Egypt, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. Similar advances occurred in other riverine civilizations (the Indus, the Yellow River, and the Yangtze). Breakthroughs included technological and institutional advances in agriculture, public administration, writing and communications, engineering, and long-distance trade. These breakthroughs gave rise to city-states and to larger political units.

The earliest kingdoms of a unified Egypt were founded around 3000 BCE, roughly contemporaneous with the rise of the first dynasties in Mesopotamia, beginning with the early dynasty of Sumer around 2900 BCE. Both Egypt and Sumer had early writing systems, the hieroglyphics of Egypt and the cuneiform (wedge-shaped) writing of the Sumerian language, which provided an invaluable tool for public administration. Unified dynasties ruled Egypt for most of the period until the neo-Assyrian conquest of Egypt around 670 BCE, followed by brief conquests by Babylonians and afterwards by Achaemenid Persia. In Mesopotamia, a number of dynasties rose and fell during this same period, including the first empire of Mesopotamia, the Akkadian Empire (c. 2350–2100 BCE), followed by Assyrian and Babylonian kingdoms. The largest of the Mesopotamian kingdoms would be the neo-Assyrian empire (tenth to seventh century BCE), which conquered the Levant and Egypt and which in turn was conquered by the Persians.

These Fertile Crescent civilizations achieved an astonishing number of breakthroughs during this period. They created early written legal codes, including the Code of Hammurabi (Babylonia, c. 1790 BCE), which became models of legal codes throughout the classical world. They created grand public structures, not least the pyramids, and considerable public infrastructure. They built cities and established methods of public administration and tax collection. They made breakthroughs in writing systems and historical documentation. They created new philosophies and religions that would profoundly influence Judaism and Christianity. They made great advances in a range of scientific fields, including mathematics, astronomy, engineering, metallurgy, and medicine. And, of course, these kingdoms engaged in long-distance trade and long-distance warfare, both dependent on the horse. Chariots and cavalry became core features of the Near East military from around 1500 BCE. Horses and donkeys as pack animals were vital for long-distance trade, transporting precious stones, spices, gold, other metals, cloth, and artisanal works.

By the end of our period, 1000 BCE, a large number of urban centers dotted the lucky latitudes of Eurasia. A recent study of ancient cities documents twenty-six Eurasian cities with populations of ten thousand or more between the years 800 BCE and 500 BCE, the legacy of the Equestrian Age.9 Strikingly, as we see in figure 4.6, all of these urban sites except one (Marib, Yemen) lie in the lucky latitudes, a vivid illustration of the uniquely favorable development conditions in that narrow band, and almost all are either in the temperate zones in China and the Mediterranean littoral or along river valleys in the drylands (notably in Egypt and Mesopotamia).

4.6 Ancient Urban Centers Were Concentrated in the Lucky Latitudes

The period from 3000 to 1000 BCE was transformative for the major civilizations of Eurasia. Three profound technological breakthroughs were most decisive: the domestication of the horse, the development of writing systems, and the breakthroughs in metallurgy. These were accompanied by dramatic advances in public administration, religion, and philosophy, especially in the Fertile Crescent. By the end of the Equestrian Age, around 1000 BCE, large land empires were beginning to emerge beyond their riverine home base. The first was the neo-Assyrian empire, which would briefly conquer Mesopotamia, the Levant, eastern Anatolia, and Egypt. Yet that empire merely set the stage for even larger empires that would arise across the lucky latitudes of Eurasia. That is the story of the Classical Age, to which we now turn.