As of 1500, we arrive at a pivotal moment in human history, when the Old World and the New World were suddenly reunited through oceangoing vessels, and when Europeans first sailed to Asia by circling the Cape of Good Hope at the Southern tip of Africa. For the first time in more than ten thousand years, ever since the land bridge Beringia between Asia and Europe was submerged at the beginning of the Holocene, there resumed an active interchange between the Old World and the Americas. Two voyages of the 1490s—those of Christopher Columbus from the Atlantic coast of Spain to the Caribbean in 1492 and of Vasco de Gama from Lisbon to Calicut, India, in 1498 and back in 1499—decisively changed the direction of world history. Humanity’s understanding of the world and our place in it, the organization of the global economy, the centers of global power, and the decisive technologies of society were all upended by the new era of ocean-based globalization. Yet before we can appreciate the vast implications of these two voyages and their aftermath, we should first address a more basic question: Why did Western Europe rather than East Asia come to dominate the seas, and thereby the world?

In the early fifteenth century, China’s navigational capacity was second to none in the world. The famed seven voyages of Admiral Zheng He during the early Ming Dynasty, in the first three decades of the fifteenth century, are justly remembered hundreds of years later as remarkable naval accomplishments of China.1 These voyages of enormous fleets sailed from China to Southeast Asia, through the South China Sea and the Malacca Pass, around Java and Sumatra, into the Indian Ocean, and all the way to East Africa, Arabia, the coasts of India, and back to China. The route of the fourth voyage, 1413–15, is shown in figure 6.1.

6.1 Zheng He’s Fourth Voyage, 1413–1415

These great voyages were a triumph of naval technology, a remarkable demonstration of China’s grandeur, and an act of Chinese statecraft. The first voyage is described as consisting of a fleet of 317 ships with twenty-eight thousand crewmen; the other six voyages were of similar scale. One of the key goals of the Ming emperor was to ensure that all the countries of the Indian Ocean understood clearly the geopolitical ordering of the time. China was the undoubted Middle Kingdom, the one to which all other kingdoms should pay tribute and obeisance. The voyages aimed to establish a system of tributary trade. The visit by the Chinese fleet was to be followed by return visits by representatives of the respective kingdoms to China. In those latter visits, these states would pay tribute to the Middle Kingdom and in return receive reciprocal gifts from China. At the same time, private commercial trade independent of the tributary trade was highly restricted. Indeed, in 1371, the Ming emperor had prohibited purely private trade.

Zheng He’s patron and sponsor was the Yongle emperor (r. 1402–24). Upon the emperor’s death, his son discontinued the voyages on the grounds that they were unnecessary, expensive, and a violation of Confucian principles. The son died in 1425, and his successor, the Yongle emperor’s grandson, ordered Zheng He in 1430 to undertake a seventh voyage. Zheng He apparently died at sea in 1433 or perhaps soon after the completion of the seventh voyage.

At that point, Chinese history took a more decisive anti-trade turn, one whose repercussions are still felt today. At a hinge moment of history, with China dominating the seas, and its naval power and abilities far surpassing anything known by Europeans, the Ming Dynasty largely abandoned the high seas, called off further voyages, and drastically reduced its fleet. Port facilities were scaled back, and the coastal population declined, signaling a decline in overall commercial maritime activity. While historians still debate the extent to which international commercial trade was ended, China surely downplayed the importance of the oceans in its future statecraft. One common argument is that the continuing threat of steppe warriors on the northern border led China to look northward rather than oceanward. Another argument is that Confucian bureaucrats of the Ming Dynasty looked askance at commercial activity.

The ramifications were profound. China largely abandoned the competition for the Indian Ocean at just the moment that two small kingdoms on the Atlantic coast, Portugal and Spain, began to increase their interest in oceangoing navigation and trade. Instead of China circling the Cape of Good Hope en route to Europe, it was European powers that circled the Cape of Good Hope en route to Asia. And within a century of 1433, it was the gunboats of Spain, Portugal, and other European powers that were plying the waters of the Indian Ocean and circumnavigating the Earth. China gradually ceded its technological leadership and fell behind Europe in the sciences, engineering, and mathematics. By the nineteenth century, the gap in technological capacity was so large that China’s sovereignty was compromised not by its northern neighbors as in the past, but by North Atlantic European nations that were far less populous than China and halfway around the world.

Writing in 1776, 340 years after the last voyage, Adam Smith described China in this way:

China has been long one of the richest, that is, one of the most fertile, best cultivated, most industrious, and most populous countries in world. It seems, however, to have been long stationary. Marco Polo, who visited it more than five hundred years ago, describes its cultivation, industry, and populousness, almost in the same terms in which they are described by travellers in the present times. It had perhaps, even long before his time, acquired that full complement of riches which the nature of its laws and institutions permits it to acquire.2

That China was “stationary” for this long period was likely due in part to its having abandoned the gains in technological and scientific knowledge that would have accompanied more vigorous ocean-based commercial trade. Only in 1978, 545 years after the end of the seventh voyage, would China again enthusiastically embrace open world trade as a core policy of statecraft.

On the other side of Eurasia, a very pioneering king of a small nation, King Henry the Navigator of Portugal, was encouraging naval exploration and advances in navigational technology with Portuguese caravels venturing down the coast of west Africa. Eventually those farsighted efforts would culminate with the Portuguese navigator Bartolomeu Dias reaching the southern tip of Africa, the Cape of Good Hope, in 1488. Then, with the help of Arab or Indian sailors in the Indian Ocean, Vasco da Gama sailed around the southern tip of Africa to the Calicut coast of southern India in 1498.

The main reason that Europeans were searching for a sea route to Asia was the knock-on effect of the fall of the Eastern Roman Empire. In 1453, the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II defeated the Byzantine emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos and occupied Constantinople. With the Ottoman Empire reigning in the newly named Istanbul, the ancient silk routes and sea routes to Asia were at risk. (The sea routes involved Mediterranean trade to a port in Egypt or the Levant, land portage to the Indian Ocean via Suez or the Arabian Peninsula, and then sea-based trade with Arab merchants to India or China.) Navigation in the eastern Mediterranean was under the threat of the Ottoman fleet, and the challenge of finding an alternative sea route to Asia became urgent.

The rulers of Western Europe gained a new and keen interest in ocean-based navigation. Suddenly, the countries of the North Atlantic (Spain, Portugal, Britain, France, and Holland) had the upper hand of geography compared with the previous longtime leaders of east-west trade, Genoa, Venice, and Byzantium. Fittingly, in 1492, the same year that saw the completion of the Christian reconquest of Spain from the long reign of Islamic powers, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella sponsored the voyage of Christopher Columbus, who proposed to sail west across the Atlantic to find a new sea route to Asia. (The third act of 1492, sadly, was the expulsion of the Jews from Spain.)

The rest, one might say, is history. Rather than reaching India, Columbus stumbled upon the Americas (figure 6.2), though he still believed he had reached India. Vasco da Gama, for his part, sailed from Lisbon and made it to India and back in 1498–99 (figure 6.3). The race was now on, initially between Portugal and Spain, to earn the spoils from these two historic breakthroughs. More fundamentally, these two voyages reconnected the entire inhabited world for the first time in more than ten thousand years, ever since the rising ocean level at the end of the Pleistocene had submerged the Beringia land bridge between Asia and North America.

6.2 Columbus’s First Voyage, 1492–1493

6.3 Vasco da Gama’s First Voyage, 1497–1499

As noted by the great environmental historian Alfred Crosby, Columbus’s voyages produced much more than a meeting of Europeans and Native Americans. They created a sudden conduit for the unprecedented two-way exchange of species between the Old World and the New—plants, animals, and disastrously, pathogens. This two-way exchange, which Crosby calls the Columbian exchange, was biologically unprecedented, with profound consequences that have lasted to the present day.3

The most obvious effect was the exchange of crops between the Old World and the New, along with the introduction of many domesticated animals into the Americas for the first time. The Americas offered the Old World such staples as maize, potatoes, and tomatoes. In return, the Old World offered wheat and rice, crops that had never before been cultivated in the Americas. Suddenly, too, there were farm animals: horses in North America for the first time in ten thousand years, along with cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs. Addictive crops also flowed in both directions: tobacco from the Americas to Europe, and sugarcane to the Americas, a crop that would fundamentally transform the Caribbean and the European economies. Other crops in the two-way exchange are shown in figure 6.4.

6.4 The Columbian Exchange of Crops, Animals and Pathogens

The arrival of Europeans and their livestock also brought Old World diseases to the Americas, diseases that that the indigenous populations in the Americas had never previously encountered and to which they therefore had no genetic or acquired immunity. The Old World delivered almost all of the pathogens in a one-way exchange to the Americas; few, if any, diseases were transferred from the Americas to the Old World. The reason is that most of the diseases of the Old World began in animal reservoirs, notably in domesticated farm animals, which were not present in the Americas. Since the indigenous Americans had few domesticated farm animals, they had few novel zoonotic (animal-to-human) diseases to transmit to the European arrivals.

The list of newly arrived diseases from Europe was long and deadly including smallpox, influenza, typhus, measles, diphtheria, and whooping cough. Smallpox was the mass killer; it wiped out a shocking proportion of the native populations encountering the newly arrived Europeans. African slaves and slave traders also transmitted two mosquito-borne pathogens, malaria and yellow fever, from Africa to the New World. There is a remaining question as to whether new microbial pathogens were in fact transmitted from the Americas back to Europe. One candidate is syphilis, which had its first outbreak in Europe in 1495. There remains considerable controversy among three possibilities: that syphilis existed in the Old World but was not diagnosed; that syphilis was brought to Europe by Columbus’s returning crew; or that European syphilis was a mutated form of the bacterium Treponema brought back from the Americas. Recent evidence points toward the New World origin of the disease.4

There is also a continuing debate about the demographic impact of the Columbian exchange because there is substantial uncertainty about the size of the native populations in the Americas prior to European arrival. Estimates of the population of the Americas on the eve of Columbus’s arrival have varied enormously, from a few million to 100 million or even more. A recent very careful assessment by Alexander Koch and colleagues has produced the estimates shown in table 6.1. According to these estimates, the indigenous population in 1500 stood at 60.5 million. By 1600, the population had declined by 90 percent, to just 6.1 million.5

Table 6.1 Estimates of Population and Land Use in the Americas, 1500 and 1600

|

1500 |

1600 |

| Population (millions) |

60.5 |

6.1 (−90%) |

| Land use per capita (hectares) |

1.04 |

1.0 |

| Land use (millions of hectares) |

61.9 |

6.1 (−90%) |

| Net carbon uptake (GtC) |

– |

7.4 (from 1500 to 1600) |

Source: Data from Alexander Koch, Chris Brierley, Mark M. Maslin, and Simon L. Lewis, “Earth System Impacts of the Europrean Arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492.” Science Direct 207 (March 2019): 13–36

One result of this catastrophic decline in population was a commensurate decline in the land in the Americas used for farming. With land use per capita around one hectare, the fall in population resulted in a reduction in land use of some 55 million hectares. Much of this land returned to forest or other vegetative cover, leading to a biological drawdown and storage of atmospheric carbon, which the authors estimate to have been on the order of 7.4 billion tons of carbon (GtC) between 1500 and 1600, or a drawdown of roughly 3.5 parts per million of CO2 in the atmosphere. This reduction of atmospheric CO2, in turn, likely played a role in the observed cooling of the Earth’s temperature in the sixteenth century, which is estimated to have been around 0.15 degrees Celsius. This slight cooling has sometimes been termed the Little Ice Age in Europe in the 1500s.

Whatever the case with climate, the decline in native populations was undoubtedly tragic and catastrophic. Disease was the major initiating factor, but war, plunder, conquest, and subjugation of indigenous communities and destruction of their cultures also no doubt contributed. Even today, the Americas remain sparsely populated relative to Europe and Asia. The population densities of the continents (population per km2) as of 2018 are estimated as follows: Asia, 95; Europe, 73; Africa, 34; North America, 22; South America, 22; Australia, 3.

The strategic situation for the European nations was different in the Indian Ocean. There, the Europeans faced populous and long-established societies with sophisticated military capacities and, unlike in the Americas, a shared pool of pathogens with the arriving Europeans. Yet the Europeans were still able to gain a foothold to establish both a commercial and a military presence. Over time, they came to dominate the Indian Ocean sea-lanes despite being interlopers from thousands of miles away. Their advantage lay heavily with military technologies that had originally arrived from China but were now turned to Europe’s advantage: gunpowder and well-protected fortresses.

Gunpowder was first developed in China in the Song Dynasty, and the earliest guns were developed there as well. Yet it was in Europe that these technologies were pushed forward. Gunpowder and early guns may have been brought to Europe by the Mongols, who had adopted the technology from the Chinese. The European powers, heavily engaged in wars within Europe, quickly innovated cannons of increasing power and accuracy and placed them on oceangoing galleons and other ships.

These cannon-laden ships gave the European nations the military advantage to establish new colonies, trading posts, and fortresses throughout the Indian Ocean. While China and other Asian countries rather quickly emulated the new artillery arriving from Europe, the early military advantage of the European naval powers was enough to establish beachheads in several strategic outposts. The gains in trade that resulted for Europe were matched by losses in the authority, prestige, and trading income of China. China’s tributary system largely collapsed, both because of China’s self-imposed withdrawal from the Indian Ocean and because of the rising military strength of the European powers in the Indian Ocean.

The fall of Constantinople and the discovery of the sea routes to the Americas and Asia did more than reroute global trade. These events also rerouted the European mind. The discovery of new lands based on new technologies radically altered the European worldview. The Americas were not mentioned in the Bible, nor were the species of plants and animals that the Europeans discovered there. Here truly was something new under the sun.

Three other currents of the time contributed to a radical change in the European worldview regarding empiricism, science, and technology. The first was the flood of Greek scholars to Europe after the fall of Constantinople to the Turks. A great concentration of philosophical learning, with roots back to ancient Greece, suddenly showed up in Western Europe, with Greek scholars arriving to the Italian universities at Bologna, Naples, Padua, and Siena.

This flood of scholarship was a prime factor in the second great tide of the times, the arrival of the Renaissance in Western Europe. The rediscovery of the arts, philosophy, and great learning of ancient Greece and Rome was already under way in the first half of the fifteenth century but was given an added spur by the fall of the Eastern Roman Empire. The Renaissance had its roots as well in the growing commerce and urbanization occurring throughout Western Europe, but notably in northern Italy, the Netherlands, and southern Germany. Florence, with its burgeoning trade and industry in woolens, was a center of the new Renaissance learning and arts.

The third great event of the age was the invention (or, in part, the reception from China) of printing with movable type, led by Johannes Gutenberg around 1439 in Mainz. This invention dramatically reduced the cost of books and quickly led to the establishment of more than a hundred printshops in Europe by 1480. An estimated 20 million book copies were printed by 1500, and the numbers would soar in the coming century. The age of learning was spurred immeasurably by the rapid dissemination of knowledge through low-cost printing.

The cumulative impact of these trends was an era of revolutionary thought, as dogma and accepted wisdom flew by the wayside. The 1510s are certainly among the most remarkable years of human thought in modern history. In 1511, the humanist scholar Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam published his satirical critique of the church, In Praise of Folly. In 1513, Nicola Machiavelli of Florence published The Prince, his handbook of power for European princes. In 1514, Nicolaus Copernicus, in Krakow, circulated an early draft of his heliocentric theory, Commentariolus, which was formally published three decades later. In the following year, 1515, Sir Thomas More published Utopia, focusing European minds on the possibilities of political and social reform. And in 1517, Martin Luther posted his Ninety-Five Theses on the church door in Wittenberg, setting off the explosion of the Reformation.

While these remarkable events did not point to any single intellectual outcome, they represented an unleashing of intellectual ferment across Europe and led to remarkable advancements of knowledge. (The Reformation also led to spasms of violence between Catholics and Protestants that would rage for centuries.) The intellectual ferment gathered into Europe’s scientific revolution, with Galileo’s discoveries at the end of the sixteenth century in turn leading the way to Newton’s physics in the mid-seventeenth century. These historic breakthroughs were accompanied by a surge in experimentation and an intense interest in engineering and new technical devices, in part to address military challenges. At the start of the seventeenth century, Francis Bacon enunciated, in Novum Organum, the new scientific method of experimentation and the age’s emerging belief that directed scientific research would improve the world, or perhaps conquer it. In 1660, Britain’s greatest minds, following the path set by Bacon, launched a new Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, and in 1666, King Louis XIV of France launched the French Academy of Sciences, creating important new institutions to promote the new scientific outlook.

Europe’s universities and scientific academies offered an astoundingly fruitful knowledge network unmatched in scale and depth by any other part of the world. Some of the new European sciences disseminated globally through the remarkable work of the Jesuit order of the Catholic Church.6 The order was founded with the approval of Pope Paul III in 1540 by ten graduates of the University of Paris led by Ignatius de Loyola. Jesuit missionaries promptly set forth across the oceans to Portuguese and Spanish settlements to establish new centers of missionizing and learning, some of which would become Jesuit colleges and universities. The Jesuits may plausibly be credited with creating the first global network of higher learning, with Jesuit schools and printing houses quickly established across Europe, and Jesuit missionary and teaching activities established overseas in South America, India, Japan, China, the Philippines, and Portuguese colonies of Africa.

These far-flung Jesuit missions collated new global knowledge of botany and geography, and during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, brought many advances of European science and mathematics to the Mughal court in India, the Ming Dynasty in China, early Tokugawa Japan, and elsewhere. The Jesuits also displayed remarkable moral valor in defending the rights of native populations against the depredations of the Portuguese and Spanish colonists, often at extreme danger and duress to the Jesuit missionaries themselves at the hands of the colonial authorities and slave traders.

Europe’s new global-scale trade with the Americas and with Asia also marked the birth of global capitalism, a new system of global-scale economic organization. The new economic system was marked by four distinctive features:

(1) Imperial power extended across oceans and ecological zones. The temperate-zone nations of Western Europe colonized tropical-zone regions in the Americas and Asia to produce tropical products such as tobacco, sugarcane, cotton, rubber, or minerals.

(2) Production systems were globalized, with plantations and mines established in the colonized countries exporting primary commodities to the home country for industrial processing, notably in the case of cotton.

(3) Profit-oriented, privately owned corporations were chartered by European governments to carry out these global activities. The most important of these new chartered companies were the British East India Company, chartered in 1600, and the Dutch East India Company, chartered in 1602.

(4) These private companies maintained their own military operations and foreign policies under the protection of their founding charters and their states’ navies.

The European powers faced different challenges in the Americas and in Asia. In the Americas, the main goal was to exploit the natural resources of the New World, most importantly gold and silver, and over time, to produce high-value crops for the European market. These included crops found in the Americas, such as cacao, cotton, rubber, and tobacco, and crops brought by the Europeans from Africa and Asia to plant in the Americas, notably sugar, coffee, and rice.

In Asia, the first aim was to gain control over parts of Asian trade, including spices from the Indonesia archipelago, cotton fabrics from India, and silks and porcelains from China. Before 1500, trade in these commodities was largely in the hands of Arab, Turkish, and Venetian intermediaries, meaning high prices in European markets. The Atlantic powers aimed to cut out the middlemen and profit directly from European-Asian trade. Later, as European countries and private companies extended their military sway over parts of coastal Asia, they aimed to control local production as well as trade and to repress the export of Asian finished goods to Europe (e.g., Indian textiles sold in European markets) in order to protect nascent industries in Europe.

The powers of trade and production were vested in private companies that became the forerunners of today’s multinational corporations. The British East India Company and the Dutch East India Company were given monopolies by their respective governments to trade in the East Indies, with the goal of wresting control of the trade away from Portugal and Spain, which in turn had taken it from the Arabs and others. Britain and Holland, as late arrivals to Indian Ocean trade, would have to fight wars with Portugal and Spain to win their place in global trade. The British East India Company not only vanquished its rivals, but in time vanquished India as well.7

Europe’s discovery of new lands in the Atlantic Ocean and the Americas set off a brutal battle for global empire, one that continues today. The first new colonies after 1450 were in the Atlantic Ocean islands and the Americas, and then in Asia and Africa. The seafaring countries of the North Atlantic would take the lead: Portugal, Spain, Holland, and Britain, with France, Russia, Germany, and Italy entering the race for overseas colonies later.

Henry the Navigator’s expeditions around West Africa set off the scramble with the discovery of the Cape Verde islands in 1456. Portugal colonized these uninhabited tropical islands six years later, in 1462, making Cape Verde the first tropical colony of a European country. When the Spanish reconquest was completed in 1492, enabling Spain’s Christian monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella to turn their attention to oceanic trade, they backed Columbus’s attempt to find a western sea route to Asia in order to counter Portugal’s attempts to find a southern sea route around Africa. Columbus’s discovery of the Caribbean islands set up a scramble for colonial possessions between the two Iberian powers.

Portugal asserted that it had the rights to all “southern lands” based on its earlier discoveries. Spain’s monarchs turned to the Spanish pope Alexander VI, the second pope of the House of Borgia, whom they knew would be sympathetic to the Spanish cause. In 1493, the pope recognized the Spanish claims to the newly discovered lands and then, in 1494, brokered an agreement between Portugal and Spain to divide the world. According to the Treaty of Tordesillas (Spain), Portugal would own all newly discovered possessions east of a longitude line set in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, 370 leagues west of Cape Verde. Spain would own all newly discovered lands west of that meridian. (The precise meridian would be in heated dispute thereafter because of differences in estimates about the size of the Earth.)

Initially the dividing line referred just to the Atlantic Ocean, but with the voyages to Asia and Magellan’s circumnavigation in 1519, it became necessary to divide the world in Asia as well. The Treaty of Zaragoza in 1529 ostensibly drew the dividing line at the anti-meridian of the Tordesillas line (the completion of a great circle, 180 degrees opposite) in the Indian Ocean. Spain would have the lands west of this meridian, including the Philippines, while Portugal would have the lands east of the line, including the coveted spice islands in the Indonesian archipelago, the source of the highly popular and lucrative nutmeg.

The world’s newly discovered lands were thus to be divided between two Catholic nations, Portugal and Spain. Yet other newcomers had quite different ideas. From the early sixteenth century onward, two other rising Atlantic powers, Britain and Holland, both part of the Reformation that rejected papal authority, aggressively contested the papal treaties. Eventually Britain would triumph, winning the greatest global empire by the nineteenth century. In its early naval forays, Britain chose to explore a northwest passage to Asia, one that would not directly confront Portugal and Spain in the tropics. Hence came the British discoveries along the northern coast of North America, today’s New England and Canadian coasts.

But Britain’s voyages failed to find a northwest passage to India. As a result, Britain resorted first to piracy and then to outright military confrontation to challenge the Portuguese and Spanish claims. Britain’s naval heroes, such as Sir Francis Drake, were simply pirates or terrorists from Spain’s point of view. As the sixteenth century progressed, Britain gained mastery over naval design, building fast and maneuverable galleons that could threaten Spain’s warships. The decisive showdown came in 1588, when the Spanish monarch decided to invade Britain to put down the upstart nation. The effort failed disastrously, with Britain’s defeat of the Spanish armada, a signal event in military history that put Britain on the path to global power and Spain on the path of imperial decline.

With its growing naval power, Britain entered the imperial fray with Portugal and Spain in the East Indies as well as in the Caribbean. In 1600, Queen Elizabeth chartered the British East India Company and granted it a monopoly of trade in the East Indies. This was quickly followed by the Dutch East India Company (VOC), chartered in 1602; the French East India Company following several decades later in 1664. From the start, trade, warfare, and colonization were inextricably linked.

Spain and Portugal were the first European nations to establish global empires in the sixteenth century, with Britain and Holland scrambling to catch up in the seventeenth century. The Spanish and Portuguese empires around 1580 are shown in figure 6.5, with the effects of the Treaties of Tordesillas and Zaragoza evident. Spain controlled, or at least claimed to control, the lands of the Americas other than Brazil and eastern North America (mainly claimed by Britain and Holland), as well as the Philippines and other islands in the western Pacific. Spain also had coastal possessions around Africa. Portugal’s empire included Brazil, Atlantic islands, coastal settlements around Africa, and settlements throughout the Indian Ocean.

6.5 Spanish Portuguese Overseas Empires, With Papal Lines of Demarcation

By 1700, the world’s division of power was as shown in figure 6.6. The great land powers of Asia included the Qing Dynasty in China, the Mughal Empire in India, the Safavid Empire in Persia, and the Ottoman Empire in West Asia. The New World was now divided among four European powers: Portugal, Spain, Britain, and France. The Dutch Republic had been knocked out of the running by Britain’s victories in three British-Dutch wars of the seventeenth century. Dutch New Amsterdam became British New York as of 1664, with a temporary reversion to the Dutch in 1673 that was then reversed in 1674.

6.6 World Empires and Selected Nations, 1700.

Map by Network Graphics

Over time, the British Empire would come to achieve global naval dominance. The great naval historian of the late nineteenth century, Alfred Thayer Mahan, attributed Britain’s long-term economic and imperial success and the long-term declines of France, Holland, Portugal, and Spain, to Britain’s naval superiority over its rivals. In Mahan’s 1890 book, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783, he explained that national wealth depended on long-distance trade, long-distance trade depended on overseas colonies, and the security of overseas colonies depended on naval preeminence.8 In Mahan’s telling, Spain’s decline (and Portugal’s, under the shared crown) was inevitable after the British defeat of the Spanish armada in 1588. Holland’s relative decline in the seventeenth century followed the decline of Holland’s naval power and Holland’s subsequent reliance on the British navy. France’s loss of empire, in Mahan’s view, was determined by its naval defeats by the British in the Seven Years’ War of 1756–63.

Russia’s Land Empire of the North

While Europe’s Atlantic states were vying for transoceanic empires, Russia emerged in the eighteenth century as Eurasia’s vast land empire of the north, seen in figure 6.6. As the inheritor of the Mongol and Timurid empires, Russia became history’s second largest contiguous empire by size, 22 million km2 at its peak in 1895, second only to the Mongol empire’s 23 million km2 at its maximum extent in 1270. Only the British Empire was larger, with a land area across the globe summing to 35 million km2 at its maximum extent in 1920.9

The Russian Empire is geographically distinct: an empire of the northern climate. Taking the region of the Commonwealth of the Independent States (CIS) as our reference point, the region is approximately 70 percent in the D (cold) climate, 7 percent in E (polar) climate, and 19 percent in the B (dry climate), with essentially no land area in the tropical or temperate climates, as we see in table 6.2. Whereas Europe west of Russia is largely temperate (around 71 percent by area), and Asia is a mix of tropical, dry, and temperate regions (with A, B, and C climates totaling 76 percent by area), Russia is cold, polar, or dry.

Table 6.2 CIS, EU, and Asia by Climate Zone and Population Density

Russia’s climate had three overwhelming implications throughout the history of Russia until the twentieth century. First, grain yields were very low in the short growing seasons of the far north and the steppe regions in the south of the empire. Second, as a result, populations remained small and the population densities were far lower than in Europe and Asia. In 1400, for example, the CIS lands had a population density of fewer than one person per km2, less than one-tenth the population density of Europe and Asia. Third, as farm families struggled to feed themselves in the harsh environment, much less provide any surplus for the market or for taxation, the Russian population remained overwhelming rural until the twentieth century. The HYDE 3.1 estimates put the Russian urbanization rate at just 2 percent as late as 1800, roughly one-tenth the urbanization rate of Western Europe.10

Russia’s peasant farmers were not only impoverished and sparsely settled but also mostly enserfed until their liberation from serfdom in 1861 by imperial decree. Thus, the long legacy of Russia’s unique geography was a sparse, illiterate, and overwhelmingly unfree rural population that formed the sociological crucible of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. Under Soviet communism in the twentieth century, the lands of the Russian Empire were industrialized and urbanized via a brutal top-down one-party state that claimed tens of millions of lives in the course of forced industrialization and the collectivization of farmlands—a “second serfdom”—that was carried out by Joseph Stalin’s regime in the late 1920s and 1930s.

The remarkable scramble by the European powers for riches, glory, and colonies in the New World and Asia, and the privatization of wealth-seeking via the new joint-stock companies, ushered in a new ethos of greed. It was one thing to exploit the native populations and grab their land; it was another to create an ethos that justified such actions. The Christian virtues of temperance and charity had long preached self-control over the passions for wealth and glory. A new morality was needed to justify the remarkable efforts toward conquest and the subjugation of whole populations. Over time, the justification was the idea that conquest was a God-given right, even a responsibility, to bring civilization to the heathens. Success, moreover, was a sign of God’s favor and providence. There were demurrals, to be sure. The Spanish monarchy, for instance, eventually outlawed the enslavement of native populations in the Americas in the New Laws of 1542. Yet those demurrals were limited, to say the least. The age of global empire was also an age of monumental cruelty, with ruthless greed built into the emerging capitalist order.

By the eighteenth century, a new ideology was taking form, especially in Britain, that “greed is good” (to use a recent summary formulation), because greed spurs a society’s efforts and inventiveness. By giving vent to greed, the logic goes, societies can best harness the insatiable ambitions, great energies and ingenuity of their citizens. While greed by itself might be unappetizing and seem to be antisocial, the unleashing of greed could in fact lead to the common good. Thus was born the idea that Adam Smith would crystalize as the “invisible hand”—the idea that the pursuit of self-interest by each person promotes the common interest of society as a whole as if by an invisible hand. Smith himself was a moralist and a believer in personal virtues, self-restraint, and justice. Yet Smith’s concept of the invisible hand quickly became an argument to let market forces play out as they might, no matter the distributional consequences.

The first statement of this counterintuitive idea came not from Smith but from a London-based pamphleteer and poet at the start of the eighteenth century, Bernard Mandeville, in an ingenious poem called “The Fable of the Bees.” In the poem, greedy and self-interested bees create such energy that the beehive becomes the marvel of the bee kingdom. Vice produces virtues. With wit, Mandeville put it this way:

Thus every Part was full of Vice,

Yet the whole Mass a Paradice;

Flatter’d in Peace, and fear’d in Wars

They were th’Esteem of Foreigners,

And lavish of their Wealth and Lives,

The Ballance of all other Hives.

Such were the Blessings of that State;

Their Crimes conspired to make ’em Great;

And Vertue, who from Politicks

Had learn’d a Thousand cunning Tricks,

Was, by their happy Influence,

Made Friends with Vice: And ever since

The worst of all the Multitude

Did something for the common Good.

The worst of the multitude, Mandeville claims, creates the common good. It’s a view, alas, that would not have been shared by the conquered peoples on the receiving end of European imperialism.

In the theory of free trade, government is to stay clear of market forces, letting supply and demand play out as they may. This doctrine, I have emphasized, fails to address the distributional consequences of market forces that can leave multitudes impoverished. It also fails to describe capitalism as it is, and as it was from the start. Not only have capitalist enterprises often been extraordinarily ruthless in their pursuit of profit; they have often, even typically, had the power of the state at their disposal to magnify their profits and shift losses to others, sometimes to fellow citizens but more often to the weak and vulnerable of other societies.

Consider Britain’s entry into global markets in its competition with Spain and Portugal. Queen Elizabeth was a personal investor in 1577 in Francis Drake’s plan to circumnavigate the globe on his vessel the Golden Hind. Yet in addition to exploration, the real plan was piracy: to loot the Spanish fleet bringing bullion and other treasures back from South America. In 1578, Drake captured a Spanish galleon with a phenomenal haul of gold, silver, jewels, porcelain, and other treasure. On Drake’s return, the pirated gains were shared with the queen, who used them to pay off the national debt. Drake became a national hero, and went on to serve as vice admiral in the defeat of the Spanish armada in 1588.

In 1600, the launch of the East India Company marked an even more decisive breakthrough to modern capitalism. Here was a joint-stock company formed specifically to engage in multinational trade. Once again, the private investors could count on the power and beneficence of the state. Queen Elizabeth charted the East India Company as a monopoly to engage in all trade east of the Cape of Good Hope and west of the Straits of Magellan. From the start, the company paid bribes and gifts to the court and to leading politicians while acting as a state within a state in its dealings in India, complete with private army, the powers of bribery, and the protections of limited liability.

The history of the New World quickly became the drama of three distinct groups of humanity. The first were the indigenous peoples of the Americas, struck hard by Old World diseases and conquest but continuing to fight for physical, cultural, and political survival. The second were the European conquerors and settlers. The third were the African slaves brought by the millions to work the mines and plantations of the New World. The cauldron of conquest and stratification has shaped the Americas to this day as a region of sky-high inequality and conflict, yet one that would try over the centuries to forge an avowedly multiethnic and multiracial society.

The European conquerors came for glory and wealth, but grappled from the start with the fundamental question of who was going to produce that wealth. The hope, of course, was for easy riches—Eldorado, the city of gold, based on imagined vast and easy riches. The Spanish found gold and silver mines that they ruthlessly exploited in the sixteenth century, flooding Europe with precious metals, but even the mines needed workers for the backbreaking, life-threatening labor. The plantations were also brutal, requiring harsh physical labor in tropical conditions, causing heat stress, extreme vulnerability to a host of tropical diseases, and very often early death. Enticing European settlers to the tropical lands was a difficult task from the start, especially as news got back to Europe about the grim realities in the New World.

The indigenous populations survived in large numbers mainly in the less accessible mountain regions of Mesoamerica (Mexico and Central America) and the Andes (today’s Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru). Native American nations also survived in the sparsely settled regions of North America. Yet deaths were rampant in the Caribbean, along the Brazilian coast, and wherever the Europeans launched intensive mining and plantation operations. Initially, the Spanish conquerors gave grants of land and authority, so-called encomiendas, to leading figures, the encomenderos (those receiving the grants), empowering them to enslave the natives living in their lands. A heated debate quickly ensued among the Spanish elites, including the church and the monarchy, concerning the rights of the indigenous populations. The famed Franciscan friar Bartolome de las Casas argued that the Indians had souls and as such could not be enslaved or mistreated by the encomenderos. Remarkably, the monarchy agreed and in 1542 issued the Leyes Nuevos (New Laws), outlawing the enslavement of indigenous Americans. This act must be regarded as a powerful case of moral reasoning triumphing over power and greed, all too rare in human history.

Yet the net outcome was hardly satisfactory. Not only did brutal treatment of the native population continue, but the labor shortages that resulted from the New Laws and the decline of indigenous populations quickly gave way to decisions to import slaves in vast numbers from Africa. Brazil under Portuguese and Spanish rule became the main destination for the slave trade for the next two centuries. The British, for their part, did not hesitate to join the slave trade with enthusiasm, turning the Caribbean into slave colonies for hundreds of years.

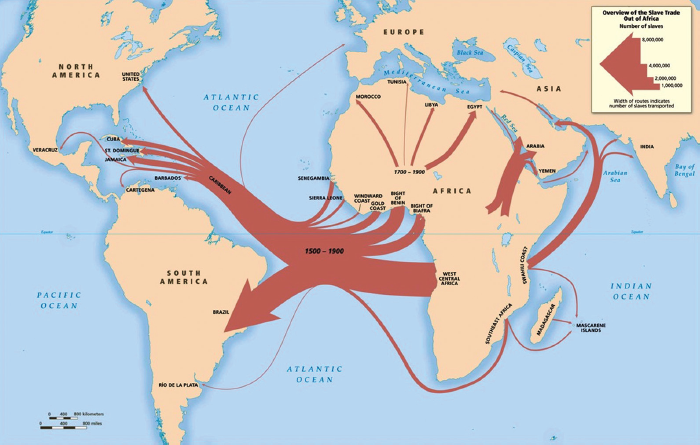

Figure 6.7 illustrates quantitatively the massive movement of slaves from Africa to the Americas in the course of an estimated thirty-six thousand voyages between 1514 and 1866, as well as smaller transport of slaves to North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and other destinations in the Arabian Sea. The map is based in part on a painstaking calculation of the number of Africans transported in the brutal “middle passage” from Africa to the Americas. Most African slaves brought to the New World came from the Gulf of Guinea and farther south along the Atlantic coast of Africa, especially present-day Angola, and were sent in largest quantities to Brazil and the Caribbean. Some were sent to North America, where slave labor would take hold as the basis of the cotton empire in the colonies that would become the southern United States after the American War of Independence.

6.7 The Slave Trade from Africa, 1500-1900

Source: Eltis & Richardson, ATLAS OF THE TRANSATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE (2010), Map 1 from accompanying web site, Overview of Slave Trade out of Africa, 1500–1900. Reproduced with the permission of Yale University Press.

African slaves powered the new plantation and mining economies of the Spanish, Portuguese, and British colonies, especially in the tropical regions. The most important plantation commodity was sugar, grown in northeast Brazil and the Caribbean, which together accounted for the vast preponderance of slave arrivals to the Americas, and also the Peruvian coast. Slaves were also directed to the mines of Mexico and the Andes, to the coffee plantations of Brazil and Mesoamerica, and to tobacco and cotton plantations in the southern United States. Slaveholding was mainly a tropical matter; free laborers from Europe would not accept the deadly conditions of farmwork in the neotropics, especially after falciparum malaria became prevalent following its introduction into the Americas from Africa by the slave trade itself. While some slavery existed in the temperate zones of the Americas, slavery never took hold in large numbers and was abolished far earlier in the temperate zones than in the tropics. The northern U.S. states abolished or began to phase out slavery by the early 1800s, while slavery in the southern states ended only with the Confederacy’s defeat in 1865 in the U.S. Civil War. Slavery ended in Spanish Cuba only in 1886, and in Brazil in 1888.

With the slave plantations in the Americas arose the infamous three-way trade pattern commonly known as the “triangular trade.” The slave colonies of the Americas imported slaves and exported slave-made products—sugar, cotton, and tobacco—to Europe. Europe imported the commodities and exported manufactured goods, including textiles, weapons, and metals, to Africa. And African chieftains exported slaves to European slave traders in return for Europe’s manufactured goods.

The colonization of the Americas and the expanded trade with Asia also unleashed a new frenzy of consumerism in Europe, marked by soaring demand for spices from Asia and Africa. The most sought after products were tea, silks, and porcelain from China; fine textiles from India; coffee from Yemen; and a trio of addictive products from America’s new colonial plantations—sugar, coffee, and tobacco. Portugal and Spain brought sugarcane cultivation from Iberia to Brazil and the Caribbean. The Dutch first brought coffee cultivation to their Caribbean colony, Martinique, from plantations on Java. Tobacco, native to the Americas and smoked by Native Americans, was introduced to the European colonizers, who then established tobacco plantations in the Caribbean and on the North American mainland, especially around Virginia.

Sugar, coffee, and tobacco all set off a surge of demand in Europe and, in turn, soaring profitability of plantations in the Americas. All three crops, however, were arduous to grow in the unhealthy tropical and subtropical climates of the Caribbean, Brazil, and the southern parts of North America. The demand for African slaves, therefore, soared as well. Around half of all African slaves brought to the Americas worked in the sugar plantations, mostly in the Caribbean, which overtook Brazil in sugarcane production by the eighteenth century. The overriding demographic reality of the sugar plantations was the shockingly high mortality rate, with up to a third of the newly arrived slaves dying within their first year.

In total, an estimated 14 million Africans were carried as slaves during this period. This was truly a grim and horrific stage of global capitalism. The cruelty that accompanied the development of the modern world economy must not be forgotten, because that cruelty shows up in other ways today; human trafficking is one of the greatest examples, which also continues in the form of bonded labor and child labor as part of global supply chains. Humanity is not done with the horrific abuse of others in pursuit of greed and profit.

The British and Dutch East India companies may rightly be considered the first corporations of modern capitalism. As profit-driven and greed-based joint-stock companies, they set the tone and behavior for what was to come. As described by historian Sven Beckert in his book Empire of Cotton: A Global History, much of their early business in the 1600s was trade in cotton fabrics, purchased in India for sale in Africa to slave traders and in Europe to the growing urban population. Then, in the eighteenth century, as Britain protected its domestic textile manufacturers against Indian imports, British manufacturers increasingly demanded a supply of raw cotton. The demand multiplied with the mechanization of spinning and weaving, and then with the introduction of steam power into the textile mills.

As Beckert observes, this made Britain’s cotton manufacturing “the first major industry in human history that lacked locally procured raw materials.”11 Thus began a new episode of global capitalism, with British businesses frantically seeking to secure increased access to raw cotton supplies for Britain’s booming textile industry. The “salvation,” of course, came in the form of slaves, growing the “white gold” in the plantations of the Caribbean and Brazil. Yet even then, upheaval hit the industry with the slave rebellion in Saint-Domingue in 1791, giving birth to an independent Haiti. Britain’s raw material inputs were suddenly in jeopardy.

Once again, a solution arose, seemingly providentially from the industry’s point of view. The U.S. South would provide the land and the slave labor to feed Britain’s mills. Beckert explains the essence of this solution:

What distinguished the United States from virtually every other cotton-growing area in the world was planters’ command of nearly unlimited suppliers of land, labor, and capital, and their unparalleled political power. In the Ottoman Empire and India, as we know, powerful indigenous rulers controlled the land, and deeply entrenched social groups struggled over its use. In the West Indies and Brazil, sugar planters competed for land, labor, and power. The United States, and its plentiful land, faced no such encumbrances.12

This alliance of British industry and capital with U.S. slavery was to last from the 1790s until the Civil War. Far from slavery being an outmoded system alien to modern capitalism, slavery was at the very cutting edge of global capitalism, creating vast wealth on the foundations of untold misery. The brutality of the Anglo-American system is underscored by the fact that the United States was essentially the only country in the world where it took a civil war to end slavery. Even tsarist Russia ended serfdom peacefully, with Tsar Alexander’s Emancipation Decree of 1861, just as the United States, ostensibly the land of freedom, was sliding into civil war.

Europe’s global empires, spanning oceans and continents for the first time, unleashed another new phenomenon, global war, also spanning oceans and continents. From the late seventeenth century on, major conflicts among the European powers involved battles on several continents. The implications were dire. More and more of the world would be swept into Europe’s wars, so that eventually the two world wars of the twentieth century each claimed tens of millions of lives across the globe.

The Nine Years’ War of 1688–97 might be considered the first global war, as it was fought simultaneously in the Americas, Europe, and Asia. The main European combatants were France under Louis XIV facing a coalition of Britain, Holland, and the Holy Roman Empire. The main theaters of the war were in Europe, along France’s borders, following the attempts by Louis XIV to expand France’s influence into neighboring countries. Early in the war with France, Holland’s monarch William of Orange successfully invaded Britain and took the throne from King James II, an invasion subsequently known as the Glorious Revolution of 1688. The war became global when news of the conflict reached the Americas and Asia. In North America, the war, known as King William’s War, mainly involved British colonialists and their Native American allies against French colonialists and their Native American allies. It would be the start of several wars between France and Britain fought in North America. In Asia, the fighting was between the French and Anglo-Dutch forces in southeast India, notably Pondicherry. While the battles in the Americas and India were not decisive, they set the pattern for the coming centuries of European wars spilling over to the Americas, Asia, and eventually Africa as well.

The next global war was the Seven Years’ War between 1756 and 1763. This one was a five-continent conflict—Europe, North America, South America, Africa, and Asia—between two European grand coalitions, one led by Britain, with Portugal, Prussia, and other German principalities, and the other led by France, with the Austrian (Holy Roman) Empire, Spain, and Sweden. This war, like the Nine Years’ War, began in Europe as a contest between Austria and Prussia for control over Silesia, but it quickly spread worldwide. In the Americas, it was preceded by skirmishes between British and French colonists but after 1756 led to a broad contest for territories throughout the Americas and the Caribbean. The main result of the war in the Americas was France’s loss of territories to Britain and Spain. In Africa, the British navy conquered France’s colony in Senegal, and much of the colony was transferred to Britain by treaty at the conclusion of the war. In southern India, France’s holdings were reduced by British victories.

France quickly got even with its rival Great Britain during the U.S. War of Independence, beginning in 1776. France’s active intervention on the side of the breakaway British colonies was decisive for the Americans’ victory in their war of independence. Yet in the escalating contest between France and Britain, each victory contained the seeds of a future reversal. France’s heavy financial outlays in support of American independence contributed to France’s financial crisis of the 1780s that in turn fomented the unrest leading to the 1789 French Revolution. The French Revolution, in turn, unleashed a new round of bloody European wars from 1793 to 1815. The latter part of the French Revolutionary Wars became known as the Napoleonic Wars with the rise of Napoleon to First Consul of France in 1799 and then to Emperor of France in 1804.

The Napoleonic Wars, the bloodiest yet, cost millions of civilian and military casualties and was again fought in theaters across several continents, including Europe, North America, South America, Africa (Egypt), the Caucasus, and the Indian Ocean. These were “total wars,” with a mass mobilization of the population, mass conscription, and massive civilian casualties. The main geopolitical results of Napoleon’s defeat in 1815 were the rise of Britain to European supremacy over the oceans and the nearly fatal weakening of the Portuguese and Spanish empires, both of which had been conquered by Napoleon. Within a few years of the end of the Napoleonic Wars, both Portugal and Spain would lose most of their colonial possessions in the Americas to wars of independence.

As of 1830, Europe’s empires were as shown in figure 6.8. The Americas were now mostly independent nations, with Britain maintaining colonial possessions in Canada and the Caribbean and other European countries maintaining some island colonies in the Caribbean. Africa was as yet colonized only on the coasts, other than the British and Dutch settlements in the hinterlands of South Africa. The rest of Africa succumbed to European imperialism only toward the end of the nineteenth century, for reasons described in the next chapter. In Asia, Britain now dominated much of India and Malaya, as well as Australia, while Holland maintained its colonies in the Indonesian archipelago. Spain and Portugal each held some Asian colonies as well, including the Philippines under Spain and eastern Timor under Portugal.

6.8 World Empires and Selected Nations, 1830

Much of the ensuing drama of nineteenth-century economic development would take place on the mainland of Europe, which pioneered the new age of industrial globalization.

Adam Smith, the great inventor of modern economic thought, living in Scotland in the eighteenth century, published his magnum opus, The Wealth of Nations, in 1776. As a great humanist, he observed the consequences of globalization with a globalist perspective rather than British partiality. (In his own work on moral sympathy, Smith spoke about the “impartial spectator” as the vantage point for moral reasoning.) This is what Smith had to say about this remarkable fourth age of globalization. I quote him at length because it is wonderful to listen carefully to a great mind like Smith’s reflecting on such pivotal events. His words inspire us to think hard and with sympathy about our own times.

The discovery of America, and that of a passage to the East Indies by the Cape of Good Hope, are the two greatest and most important events recorded in the history of mankind. Their consequences have already been very great; but, in the short period of between two and three centuries which has elapsed since these discoveries were made, it is impossible that the whole extent of their consequences can have been seen. What benefits or what misfortunes to mankind may hereafter result from those great events, no human wisdom can foresee. By uniting, in some measure, the most distant parts of the world, by enabling them to relieve one another’s wants, to increase one another’s enjoyments, and to encourage one another’s industry, their general tendency would seem to be beneficial. To the natives however, both of the East and West Indies, all the commercial benefits which can have resulted from those events have been sunk and lost in the dreadful misfortunes which they have occasioned. These misfortunes, however, seem to have arisen rather from accident than from anything in the nature of those events themselves. At the particular time when these discoveries were made, the superiority of force happened to be so great on the side of the Europeans that they were enabled to commit with impunity every sort of injustice in those remote countries. Hereafter, perhaps, the natives of those countries may grow stronger, or those of Europe may grow weaker, and the inhabitants of all the different quarters of the world may arrive at that equality of courage and force which, by inspiring mutual fear, can alone overawe the injustice of independent nations into some sort of respect for the rights of one another. But nothing seems more likely to establish this equality of force than that mutual communication of knowledge and of all sorts of improvements which an extensive commerce from all countries to all countries naturally, or rather necessarily, carries along with it.13

This wonderful statement is filled with humanity and relevance for us. Smith is saying that the events leading to the fourth age of globalization—the discovery of the sea routes linking Europe with the Americas and with Asia—are the most significant events of human history because they united, “in some measure, the most distant parts of the world.” But while this might have brought benefits for all of humanity through mutually beneficial trade (enabling the various parts of the world “to relieve one another’s wants”), in fact they had as of Smith’s time brought benefits to one part of humanity—namely, Western Europe—while bringing misery to the inhabitants of both the East and West Indies, who suffered from Europe’s overwhelming power. After all, the Europeans came not merely to trade but also to plunder and conquer.

Smith, remarkably, looks forward to a fairer and more balanced world, one in which the inhabitants of the East and West Indies “may grow stronger, or those of Europe may grow weaker,” in order to arrive at “an equality of courage and force” that will enable “a mutual fear,” and thereby a mutual respect. How will that come about, asks Smith? Through global trade itself. As Smith puts it, commerce will necessarily bring about the equality of force through the “mutual communication of knowledge and of all sorts of improvements.” In short, trade will cause the spread of knowledge and eventually cause the rebalancing of power. Smith is speaking about British colonialism here, but he could just as easily be speaking about our time, when China and other former colonies are achieving great advances in technological capacity and military strength through their participation in the global economy. Smith foretold a time when such a rebalancing would lead to “some sort of respect for the rights of one another.” That indeed should be the hope for our own time.

The Ocean Age gave birth to global capitalism. For the first time in history, privately chartered for-profit companies engaged in complex, global-scale production and trading networks. Private businesses, drunk with greed, hired private armies, enslaved millions, bribed their way to privileged political status at home and abroad, and generally acted with impunity. But even beyond the private greed, it was an age of conquest and unchecked competition among Europe’s powers. The world beyond the oceans was up for grabs, and little would hold back the rapaciousness that was unleashed as a result.

Adam Smith’s masterwork, The Wealth of Nations, provided a template for riches: global trade as the spur for specialization and rising productivity. Smith’s recipe worked beyond his wildest imagination. As we shall see in the next phase of globalization, productivity began to rise rapidly and persistently as new inventions expanded the market and thereby the incentives for even more inventions. The process of self-feeding growth was under way. The result would create a new kind of political power—a global superpower—that would come to be known as the hegemonic power, a global dominance achieved by Great Britain that outpaced even the scale of power and accomplishment of the Roman Empire. But, as we shall see, the gains for Britain and other major powers would often be reflected in the misery of those under their whip in the Industrial Age.