In conclusion, it is stated that the vertebrae described in the paper prove the existence of a saurian genus distinct from Megalosaurus, Steneosaurus, Poikilopleuron, Pleisosaurus, or any other large extinct reptile, remains of which have been discovered in the oolitic series; that the vertebrae, as well as the bones of the extremities, prove its marine habits; and that the surpassing bulk and the strength of the Cetiosaurus were probably assigned to it with carnivorous habitats, that is might keep in check the Crocodilians and Plesiosauri.

—RICHARD OWEN, “A DESCRIPTION OF A PORTION OF THE SKELETON OF CETIOSAURUS, A GIGANTIC EXTINCT SAURIAN REPTILE OCCURRING IN THE OOLITIC FORMATIONS OF DIFFERENT PORTIONS OF ENGLAND,” PROCEEDINGS OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON, 1842

GIANT BONES

In 1825, an amateur collector named John Kingdon was poking around an old quarry near Chipping North in Oxfordshire when he came across some huge bones. These included some gigantic vertebrae and fragments of limb bones. On June 3, 1825, Kingdon read a brief description of the bones at a meeting of the Geological Society of London and speculated that they might have come from a whale or a huge crocodile. Over the years, other collectors found more bones of the huge creature. A certain Miss Baker donated some from the area of Blisworth, Northampton, and other specimens came from Staple Hill northwest of Woodstock; from Buckingham, Garsington; and some far to the northwest in Yorkshire. Many of these bones went to the Oxford Museum, the closest scholarly institution to the finds, and others ended up in the Scarborough Museum in Yorkshire.

They all came from Middle Jurassic layers known as the Oolites, a distinctive set of limestones made of tiny particles about the size and shape of pellets from a BB gun. In those days, no one knew what produced oolites, but in the 1950s oolites were discovered forming in shallow tropical seas such as those around the Bahamas. When you slice open an oolite and examine it under the microscope, it has a concentric layered structure, like a snowball or an onion. Modern oolites have a form similar to that of tiny lime snowballs. They form when some nucleus, such as a shell fragment, rolls around in fine lime mud particles on the sea bottom due to agitated, back-and-forth currents. As it does so, it builds layer upon layer of coatings of fine lime mud around the nucleus, forming the concentrically layered “snowball” pattern we find inside. The presence of oolitic limestones is a good indicator of shallow warm tropical shoals, with frequent currents and agitated water that rolls particles around.

THE COMPLEX RICHARD OWEN

By 1841, enough specimens had accumulated of the enormous “whale” or “crocodile” that they caught the attention of Richard Owen (figure 3.1), whom we met briefly in chapters 1 and 2. Born in Lancaster in 1804, he was the son of a West Indian merchant; his mother had Huguenot ancestry. He attended schools in Lancaster, then (like Gideon Mantell) he was apprenticed to a local apothecary and surgeon to begin learning the medical trade. In 1824, he spent a year at the University of Edinburgh medical school (where he preceded Charles Darwin by one year). Dissatisfied with the situation at Edinburgh, he finished his medical education at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, mentored by the surgeon Dr. John Abernethy.

Figure 3.1

Portrait of Richard Owen. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

After earning his medical degree, Owen realized he was not cut out for the life of a country doctor and instead tried to focus on anatomy. Abernethy recommended him for a post at the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, where he soon organized and cataloged all of their collections, including the recently acquired Hunterian collection of 14,000 specimens of some 3,000 animals, many already dissected. By studying these specimens, he taught himself zoology and comparative anatomy and soon had an encyclopedic knowledge of anatomy second to none. Indeed, later in life he was nicknamed “the British Cuvier” because his talent and discoveries led people to compare him to the great Baron Georges Cuvier, the founder of comparative anatomy and vertebrate paleontology.

By 1836, he was appointed the Hunterian Professor of the Royal College of Surgeons, and by 1849 he was the curator of that collection. In 1856, he was appointed curator of the natural history collections of the British Museum, and he spent decades working hard for a new building to house the natural history collections separate from the original British Museum in the Bloomsbury section of London (which focuses on art and archaeology). Finally, in 1881 his great “cathedral to science” was dedicated in the South Kensington section of London and became the British Museum (Natural History), now called the Natural History Museum. It is still one of the world’s greatest museums with collections unrivaled by almost any other museum in the world.

Owen’s work on zoology and paleontology was amazing for his time, and he is responsible for many important discoveries, from describing the chambered nautilus, the African lungfish, the dodo, the great auk, the giant elephant birds (Aepyornis) of Madagascar, and huge moas (Dinornis) of New Zealand, to the first description of the skeleton of Archaeopteryx. Owen described the South American fossil mammals that Darwin brought back from the Beagle voyage in 1836, the extinct fossil marsupials of Australia including the rhino-sized wombats known as diprotodonts, gigantic kangaroos, and the marsupial “lion” Thylacoleo, the anatomy of the platypus, and formally named the major groups of even-toed (Artiodactyla) and odd-toed (Perissodactyla) hoofed mammals. Even though very few of his somewhat bizarre theoretical ideas have stood the test of time, his basic talent for descriptive anatomy and comparison with other animals was unparalleled. He published more than a dozen books and scientific monographs, and over 100 scientific papers. For this he received many honors in his lifetime.

Despite these accomplishments, his standing in the scientific community was marred by his personal behavior and his peculiar ideas. By all accounts, he was a very ambitious, driven man who was determined to succeed and reach the top (which he did more than once at the Hunterian Museum and then at the British Museum). He was especially jealous of people who disagreed with him, and Owen used all sorts of malicious and underhanded methods to battle his rivals or to undermine their scientific position. According to one biographer, he was described as a malicious, dishonest, and hateful individual. Another biographer called him a “social experimenter with a penchant for sadism. Addicted to controversy and driven by arrogance and jealousy.” The biographical passages written by Deborah Cadbury describe Owen as possessed by an “almost fanatical egoism with a callous delight in savaging his critics.” One of Owen’s Oxford colleagues called him “a damned liar. He lied for God and for malice.” Gideon Mantell claimed it was “a pity a man so talented should be so dastardly and envious.” Richard Brooke Freeman said it this way: “Owen: the most distinguished vertebrate zoologist and palaeontologist…but a most deceitful and odious man.” In an 1860 letter to Asa Gray, Charles Darwin described him thus: “No one fact tells so strongly against Owen…as that he has never reared one pupil or follower.”

Owen did everything he could to steal credit from Gideon Mantell (see chapter 2). Owen claimed that he and Cuvier discovered Iguanodon, completely ignoring the man who first found and described the actual fossils. He used his influence in the Royal Society to prevent some of Mantell’s papers from being published. Eventually the Royal Society threw him out of their Zoological Council for plagiarizing Mantell’s work. When Mantell was crippled and near death and unable to write or publish much, Owen had the audacity to rename some of Mantell’s dinosaurs and claim that he had found them. After Mantell’s death, Owen wrote a scathing and demeaning obituary that dismissed Mantell as a mediocre amateur naturalist and doctor with discoveries of no consequence. Even though it was published anonymously, everyone knew it came from Owen. Eventually Owen was denied the presidency of the Geological Society of London because of his petty and nasty treatment of Mantell.

When Darwin’s ideas about evolution came out in 1859, Owen was insanely jealous because his own weird ideas about nature had never gotten any traction. He did everything he could to battle against Darwin’s ideas in scientific circles, and especially with his powerful friends in high places. Darwin wrote of him: “Spiteful, extremely malignant, clever; the Londoners say he is mad with envy because my book is so talked about.” “It is painful to be hated in the intense degree with which Owen hates me.” Owen’s nastiest attack was an anonymous book review that distorted and savaged Darwin’s book while praising his own work in the third person.

Owen’s enmity soon extended to all of Darwin’s friends and supporters, including zoologist Thomas Henry Huxley, botanist Joseph Hooker, and many others. They soon became the powerful elite of British science, and Owen and his ideas became increasingly marginalized and irrelevant. When Huxley debated Archbishop “Soapy Sam” Wilberforce at Oxford in 1860, Owen coached Wilberforce on what to say because the archbishop knew no science—and Huxley could see the fingerprints of Owen’s coaching on Wilberforce right away.

When Huxley confidently showed the connection between humans and other great apes, Owen claimed that only human brains had a region called the hippocampus, which set humans apart from all other animals. Huxley did his own dissections and showed that both apes and humans had a hippocampus, and Owen never forgave him. When Owen, as the official paleontologist of the British Museum, first described Archaeopteryx in 1861, he did everything possible to minimize how good a transitional form it was between birds and dinosaurs. Huxley corrected that in print as well. Owen also did everything he could to end government funding of Kew Gardens, Hooker’s botanical marvel, and have it absorbed into the British Museum.

Despite Owen’s constant attacks, the importance of the revolutionary ideas of Darwin, Huxley, Hooker, and their allies made them the center of British natural history in the second half of the 1800s. Huxley, in particular, soon was in the top position of power in British science. He used his clout and worked hard not only to support evolution but to modernize English science education and promote a new generation of scientific labs and permanent research programs. Meanwhile, Owen and his peculiar ideas were seen as more and more of a quaint, outdated notion that no one took seriously. Owen’s reputation and his ability to hurt other scientists also declined. Owen died in 1892 at age 88, having outlived his wife and children, an embittered man whose scientific descriptions were first-rate but whose theoretical ideas have not held up well.

THE WHALE LIZARD

But what about the giant mystery bones? After more than 15 years, quite a few of the huge bones of the “whale” or “crocodile” had accumulated. Naturally they drew the attention of Richard Owen, who traveled to Oxford and Yorkshire to see them all. In 1841, he gave a presentation to the Geological Society of London in which he called all these bones the remains of some huge marine crocodile or other type of saurian. His anatomical skills demonstrated that although it was whale-sized, it was definitely reptilian, hence the name he gave it: Cetiosaurus, or “whale lizard” in Greek. All he had were some trunk and tail vertebrae, fragments of limb bones, and a few other odd pieces, so there was not really much he could say about what type of creature Cetiosaurus was. The uncertainty was so great that he made no attempt to have it reconstructed for the Crystal Palace Exhibit. All he could say was that it was a huge marine reptile, possibly an enormous marine crocodile, which is how he classified it.

A year later Owen formally coined a name for the huge land creatures that had come to light, “Dinosauria,” which means “fearfully great lizards” in Greek (not “terrible lizards” as so many books report). He meant the grouping to indicate a new class of gigantic, majestic land reptiles, totally unlike any reptiles alive today. Three genera were the original basis for Owen’s Dinosauria: Buckland’s Megalosaurus and Mantell’s Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus. Surprisingly, Owen did not include his own Cetiosaurus because he believed it was some kind of crocodile or marine reptile, and all his Dinosauria were giant land reptiles.

In later papers Owen named new species of Cetiosaurus willy-nilly, without any adequate diagnosis or description. First, in 1842, there was Cetiosaurus hypoolithicus and C. epioolithicus, depending on whether the fossils came from above (epi) the Oolitic layer (Kingdon’s specimens) or below (hypo) the Oolitic layer (the Yorkshire specimens). In a later publication that same year, Owen named four species, ignoring his previous names and also failing to diagnose the new names. These names were Cetiosaurus brevis (short), C. brachyurus (short tailed), C. medius (medium), and C. longus (long). These new species were unusual in that Owen named new species based on the same bones without justifying the change. In fact, he didn’t have enough material to reconstruct one animal, let alone four distinct species that could be reliably identified. Other scientists soon jumped into the fray, and every new find of a large saurian bone was given a new species of Cetiosaurus, making it a taxonomic wastebasket for every sauropod found in Europe. This was the norm for science at the time, and nearly every new fossil received a new scientific name whether it could be distinguished from previously named fossils or not.

OWEN VERSUS MANTELL REDUX: PELOROSAURUS

One of Owen’s inadequate species names was Cetiosaurus brevis, which was based on specimens not from the Jurassic Oolitic layers but from the Lower Cretaceous beds of the Weald—Gideon Mantell’s favorite hunting ground. They were found near Cuckfield (although not necessarily in Tilgate Quarry) in 1825 by the same John Kingdon who found the first Cetiosaurus specimens near Oxford. However, they came from a different layer, the Tunbridge Wells Sands of the Hastings Group (figure 2.1). Some of the bones in the collection, however, belonged to Iguanodon. Recognizing the mistake, Alexander Melville renamed the sauropod bones Cetiosaurus conybeari.

Meanwhile, Gideon Mantell was looking at more bones of the Wealden sauropod. He decided that the bones were so different they did not belong in Cetiosaurus but in their own genus. In 1850, he coined the name Pelorosaurus for these fossils. He was originally going to call it “Colossosaurus” until he learned that kolossos means “statue” not “giant” in Greek. Instead, he chose the Greek word pelor, which means “monster,” in coining the name Pelorosaurus. In addition to the original “Cetiosaurus brevis” bones, for £8 Mantell bought another upper arm bone (humerus) found at the same site by a local miller, Peter Fuller. The humerus showed a central medullary cavity and other structures typical of large land animals that must support their great weight against the pull of gravity. It was not the dense solid bone structure of marine animals that can take advantage of the buoyancy of water. From this Mantell correctly realized that Pelorosaurus and also Cetiosaurus were giant land animals, not marine reptiles as Owen had asserted.

Owen was angry with Melville and Mantell for correcting his mistakes, and rather than admit them he went even further. In an 1853 publication (after Mantell had died), Owen rationalized his choice of the name Cetiosaurus brevis and dismissed Melville’s attempt to rename it Cetiosaurus conybeari. In answer to the late Gideon Mantell, he restricted the name Pelorosaurus to Mantell’s new humerus fossil and put all the rest of his Wealden fossils in Cetiosaurus brevis. However, in 1859 he repeated the mistake that Melville had corrected by assigning more Iguanodon bones to Cetiosaurus. He also assigned those bones to Pelorosaurus, further confusing the picture.

The mess was not straightened out for over a century. In 1970, John Ostrom did the detective work to unscramble the complicated and confused picture of these bones. He concluded that Cetiosaurus brevis was still valid, although Owen had done it wrong and his reasons were inadequate. Cetiosaurus conybeari was based on exactly the same fossils, so that name is not valid. Over the years, most of the Jurassic bones were routinely assigned to Cetiosaurus, and Cretaceous bones were called Pelorosaurus. In 2007, Mike Taylor and Darren Naish tried to clear up the status of the proper species for Pelorosaurus, recommending the use of the name P. conybeari for it, although the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature has not yet ruled on it. The status of Pelorosaurus itself is still open for debate. It is based on the original humerus that Mantell described, plus many other bones that may or may not belong to it. The name still exists in the literature, although like many sauropods it is so incomplete that little can be said about its validity.

MORE PIECES OF THE PUZZLE

About 25 years later, more specimens of Cetiosaurus were found that helped clarify what kind of animal it was. A worker digging near Bletchingdon in 1868 found a huge right thighbone. This inspired the geologist John Phillips to dig further in this locality between March and June of 1870, and they found parts of five different skeletons. They were still mostly vertebrae, but also included most of the forelimbs and hind limbs (figure 3.2). No skull or neck was known, and the parts they had were so incomplete that the animal still could not be reconstructed.

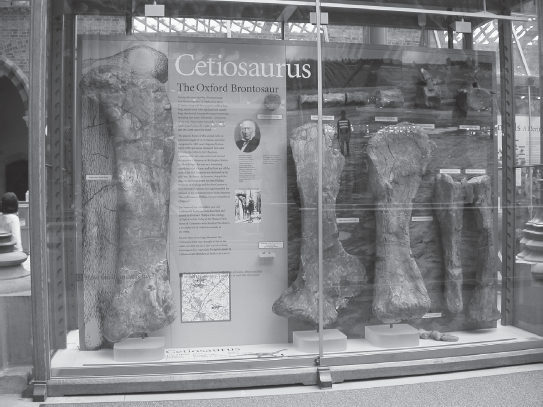

Figure 3.2

The limb bones of Cetiosaurus, on display in the Oxford Natural History Museum. There were so few bones of the skeleton that neither Owen nor most later scientists could imagine a huge long-necked, long-tailed sauropod. Owen thought it might be the remains of a giant marine crocodile. (Photograph by M. Wedel)

This is the way the situation remained for several decades in Europe. No sauropod skeleton was more than 40 percent complete, so paleontologists only knew that it was a gigantic reptile, but they could not imagine the incredibly long neck, the tiny skull with tiny teeth, or the great length of the tail that we all know today. The situation changed dramatically in the 1880s when the first complete sauropod skeletons of Apatosaurus were found in Colorado and Wyoming and eventually mounted in a lifelike pose and reconstructed by artists (see chapter 7). Suddenly the huge but incomplete pieces of European sauropods made sense. It was now possible to reconstruct Cetiosaurus similar to other large sauropods with a long neck and tail, huge size, and upright limbs—even though there were still no fossils to support this. (No skull of Cetiosaurus has ever been found.)

However, work on Cetiosaurus was not finished yet. On June 19, 1968, exactly a century after the Bletchingdon discoveries, the driver of an earthmover hit some huge bones near Rutland. More than 200 bones were found, including most of the neck vertebrae, most of the back vertebrate, the front half of the tail, and part of the hips and the right thighbone. These specimens were excavated in the next few months, then stored at the Leicester City Museum. Unfortunately, no one had the time or resources to work on them further until 1980. At that time, they finally got the specimen prepared and studied, and it has been on display at the New Walk Museum in Leicester since 1985 (figure 3.3). As mounted, the display uses most of the real bones, although some of the fragile ones are replaced by replicas, as are all the bones that still have never been found. The Rutland Cetiosaurus is the most complete sauropod, and one of the most complete dinosaurs ever found in Europe. As mounted, it is over 15 meters (50 feet) long, finally giving a true impression of Britain’s best-known sauropod dinosaur.

Figure 3.3

The reconstruction of the most complete skeleton known of Cetiosaurus in the New Walk Museum in Leicester. (Courtesy of M. Evans, New Walk Museum)

What kind of animal was Cetiosaurus? As sauropods go, it was in the medium-size range for a Jurassic form, reaching about 15–16 meters (50–55 feet) in length. Its neck was relatively short for a sauropod, but it had a relatively long tail. Its bones were robust and heavy, so it does not have all the hollowing and lightening of the bones and numerous air chambers seen in the gigantic sauropods such as Brachiosaurus. As a relatively generalized and unspecialized sauropod without a really long neck (by sauropod standards), it was probably a generalized feeder. It does not have the extreme neck and forelimb length of brachiosaurs, the extreme neck length of Mamenchisaurus, or the long necks and tails of diplodocines. It probably browsed on leaves and vegetation from low to medium heights in the tree canopy.

Most analyses of Cetiosaurus tend to suggest that it is related to the more advanced Neosauropoda, along with the Chinese taxon Shunosaurus, Omeisaurus, and Mamenchisaurus; the Argentinian Patagosaurus; Barapasaurus from India; and Chebsaurus from Africa—although it is slightly more advanced and closer to Neosauropoda than most of the rest of these primitive sauropods. Cetiosaurus was found in the same beds that yielded Megalosaurus, which may have preyed upon it when the opportunity arose. It lived in a floodplain or open woodland environment on the fringes of the shallow seas that covered most of Europe in the Middle Jurassic, and not in the marine beds where it had apparently washed out as a carcass (the same goes for Megalosaurus). Contrary to Owen’s ideas that it was an enormous marine reptile and therefore not a dinosaur, it was found in marine beds simply because those huge carcasses could float some distance.

So Cetiosaurus holds the distinction of the first sauropod discovered. But a true understanding of sauropods would not come until more complete skeletons were found in North America in the 1870s, and then in Africa and eventually China and South America in the twentieth century.

FOR FURTHER READING

Cadbury, Deborah. The Dinosaur Hunters: A True Story of Scientific Rivalry and the Discovery of the Prehistoric World. New York: Harper Collins, 2000.

——. Terrible Lizard: The First Dinosaur Hunters and the Birth of a New Science. New York: Henry Holt, 2001.

Colbert, Edwin. Men and Dinosaurs: The Search in the Field and in the Laboratory. New York: Dutton, 1968.

Desmond, Adrian. Archetypes and Ancestors: Palaeontology in Victorian London 1850–1875. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982.

Maddox, Brenda. Reading the Rocks: How Victorian Geologists Discovered the Secret of Life. New York: Bloomsbury, 2017.

McGowan, Christopher. The Dragon Seekers: How an Extraordinary Circle of Fossilists Discovered the Dinosaurs and Paved the Way for Darwin. New York: Perseus, 2001.

Naish, Darren. The Great Dinosaur Discoveries. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Rudwick, Martin. Bursting the Limits of Time: Reconstructing Geohistory in the Age of Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

——. The Meaning of Fossils: Episodes in the History of Paleontology. New York: Science History, 1976.

——. Worlds Before Adam: Reconstructing Geohistory in the Age of Reform. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Rupke, Martin. Richard Owen: Biology Without Darwin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

——. Richard Owen: Victorian Naturalist. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2004.

Spaulding, David A. E. Dinosaur Hunters: Eccentric Amateurs and Obsessed Professionals. Rocklin, Calif.: Prima, 1993.