Behold the mighty dinosaur.

Famous in prehistoric lore,

Not only for his power and strength

But for his intellectual length.

You will observe by these remains

The creature had two sets of brains—

One in his head (the usual place),

The other at his spinal base.

Thus he could reason a priori

As well as a posteriori.

No problem bothered him a bit

He made both head and tail of it.

So wise was he, so wise and solemn,

Each thought filled just a spinal column.

If one brain found the pressure strong

It passed a few ideas along.

If something slipped his forward mind

’Twas rescued by the one behind.

And if in error he was caught

He had a saving afterthought.

As he thought twice before he spoke

He had no judgment to revoke.

Thus he could think without congestion

Upon both sides of every question.

Defunct ten million years at least.

—BERT LESTON TAYLOR, “THE DINOSAUR,” 1912

“ROOFED LIZARD”

In 1877, at the height of the Bone Wars, O. C. Marsh received several crates of bones from just north of Morrison, Colorado, collected by Arthur Lakes. When the crates were opened, there were vertebrae of the back and tail, parts of the hip bones, partial limb bones, and a single piece of a flat plate, over 1 meter (3.1 feet) long. The specimen was too incomplete to accurately judge the shape of the entire animal because the front half was missing as well as most of the tail. Even so, the large flat bony plate caught Marsh’s attention. He named the creature Stegosaurus armatus (“armored roofed lizard” in Latin and Greek) in that same year and set up an order Stegosauria to include it. He imagined the creature was an aquatic turtle-like animal, with plates arranged like shingles providing a “roof” over the back. (Scientists later realized that some parts of this specimen were teeth of diplodocine sauropods and didn’t belong to a stegosaur at all.)

Even though the bones were too incomplete for any kind of reconstruction, this did not prevent some artists from imagining a version of Stegosaurus looking a bit like a bipedal lizard with spikes and plates along its back (figure 20.1). Marsh originally thought the thick dense limb bones indicated that stegosaur was aquatic. Then he decided it was a bipedal dinosaur because its front legs were so short and its hind limbs so long.

Figure 20.1

An 1884 restoration of Stegosaurus as a bipedal long-necked dinosaur with a weird arrangement of spikes and plates on its back. (From A. Tobin, 1884)

Marsh began to receive more and more bones of this mysterious creature. In 1879, he named Stegosaurus ungulatus (hoofed roofed lizard) based on specimens collected by William H. Reed from Como Bluff Quarry 12 near Robber’s Roost. Quarry 13 at Como Bluff yielded the largest concentration of stegosaur bones Marsh ever received.

In 1887, he received the best specimen of the genus, which he named Stegosaurus stenops (narrow-faced roofed lizard). He heard about the bones from a newspaper account, then paid the landowner, Marshal P. Felch and his family near Garden Park, Colorado, to let Samuel Williston quarry the bones and send them to Yale. S. stenops is now known from more than 50 specimens, including the original type specimen, which is nearly complete (figure 20.2A–B). It was found and preserved flattened on its side, so it has been nicknamed the “Road Kill” specimen. This specimen clearly showed the plates arranged in rows along the back, the short front limbs and long hind limbs, and some of the spikes near the tip of the tail.

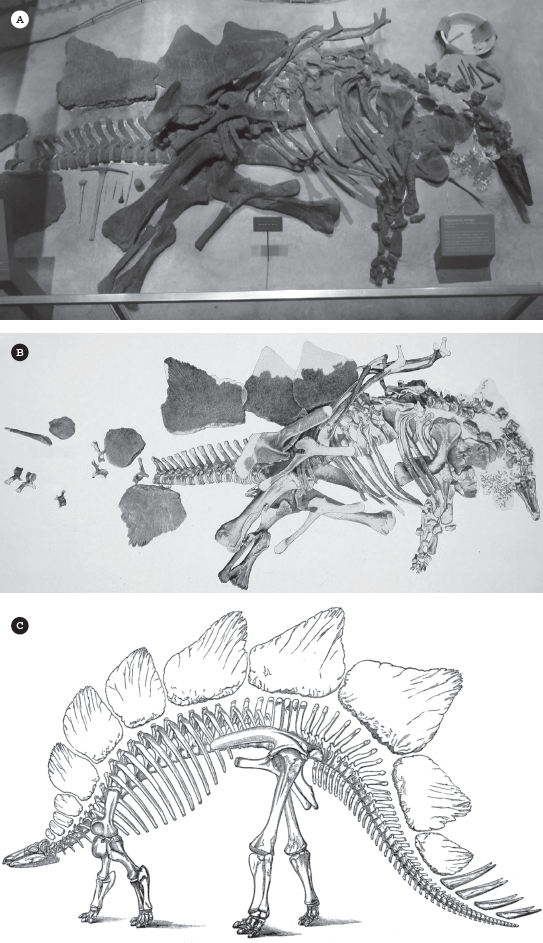

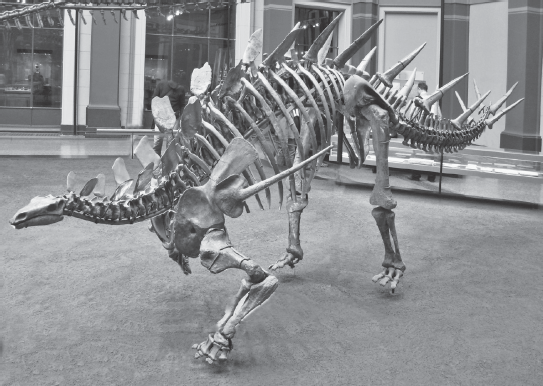

Figure 20.2

The nearly complete skeleton of Marsh’s type specimen of Stegosaurus stenops in the Smithsonian, originally from Felch Quarry in Garden Park, Colorado, nicknamed the “Road Kill.” (A) Photo of the specimen; (B) diagram of the bones showing their position and orientation; (C) Marsh’s 1891 reconstruction, showing the plates in a single row; (D) modern skeletal mount, showing the staggered alternating rows of plates and the throat armor. ([A–C] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [D] photograph by the author)

Marsh had so much material from so many different places, and he was such a taxonomic “splitter,” that in 1881 he named two additional species: Stegosaurus affinis (known from a single pubic bone that was never adequately described and since has been lost, so the name is invalid) and Diracodon laticeps (named from a few jaw fragments, also invalid). He topped that in 1887 by naming three new species. In addition to Stegosaurus stenops, they were S. sulcatus, and S. duplex. The latter two names have been abandoned because they were based on nondiagnostic specimens or trivial differences in the skeleton.

Unfortunately, Marsh’s original specimen of Stegosaurus armatus is so incomplete and nondiagnostic that his original type species is now considered a doubtful name (“nomen dubium”) and is no longer used. In 2013, the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature remedied this by ruling that S. armatus was no longer valid, and the designation of the type species of Stegosaurus was transferred to S. stenops.

By 1891, Marsh finally had enough material to accurately reconstruct Stegosaurus in a way that closely resembles what we know today: a small-headed creature with many armored plates (although he thought they were lined up in a single row) standing up along the back, spikes on the tail, short front legs, and a high arched back supported by long hind legs (figure 20.2C).

Meanwhile, Cope was trying his best to compete with the flood of bones Marsh was receiving and the torrent of new names he was publishing. In 1878, Cope received a few back and tail vertebrae and a piece of rib from his collector O. W. Lucas in Garden Park Quarry 3, nicknamed “Cope’s Nipple” (in reference to the shape of the hill). Cope gave these nondiagnostic fragments their own new genus and species names, Hypsirophus discurus. Marsh and nearly everyone else recognized that it was the same as Stegosaurus. Only Richard Lydekker used this genus in 1893 when he mistakenly used Marsh’s diagram with Cope’s name, Hypsirophus. But Cope persisted in using only his own name and never acknowledged Marsh’s name, Stegosaurus.

STEGOSAURS AROUND THE WORLD

The discovery of Stegosaurus in 1877 in Colorado was not the first stegosaur to be found, however. That honor goes to some fragmentary pieces of jaw named Regnosaurus that were collected in the Lower Cretaceous Wealden beds. They were in the British Museum collections when Gideon Mantell first saw them in 1839. At first he thought it was the as-yet-unknown lower jaw of Iguanodon, and he gave a presentation to that effect to the Royal Society on February 8, 1841. Richard Owen disputed this because the real lower jaws of Iguanodon had appeared, so Mantell decided to give the fossil a new name in 1848. Regnosaurus northamptoni gets its name from the Regni, the Roman name for the British tribe that once lived in that part of Sussex, and Spencer Compton, the second Marquess of Northampton, who was then president of the Royal Society. All that is known of this dinosaur is a lower jaw fragment and possibly some other bones from the Isle of Wight, which indicate a rather small stegosaur. Because it was so incomplete, it has been assigned to all sorts of different groups of dinosaurs, including iguanodonts, scelidosaurs, stegosaurs, hylaeosaurs, and even sauropods. In 1993, amateur paleontologist George Olshevsky revived the idea it was a stegosaur, and this was confirmed by Paul Barrett and Paul Upchurch in 1995. They found it most closely resembled the Chinese stegosaur Huayangosaurus. However, other scholars think the fossils are too incomplete to use the name at all.

In 1845, a fossil skull found in the Jurassic beds of South Africa was sent to London and described by Richard Owen. At first, he thought it belonged to the hippo-like reptiles known as parieasaurs found in the Permian of South Africa, and he assigned it to the pareiasaur genus Anthodon. It was forgotten for decades, until a South African paleontologist, Robert Broom, looked at it again in 1912 and realized it was not a parieasaur but a dinosaur, possibly an ankylosaur. He assigned it to the problematic genus Palaeoscincus (ancient skink lizard). Palaeoscincus was named by Joseph Leidy based on some nondiagnostic ankylosaur teeth, and this name has been completely abandoned as invalid in recent years. In 1929, Baron Franz Nopcsa realized that the skull belonged to a stegosaur. Unaware of Broom’s renaming of it, he renamed it Paranthodon, which turns out to be the valid name for the specimen. No additional specimens have been found beyond the original snout fragment, so the genus Paranthodon is just as enigmatic as it was when first found. All that can be said is that it is some kind of stegosaur.

Another stegosaur found before Stegosaurus itself was Dacentrurus. In May 1874, James Shopland of Swindon Brick and Tile Company found a specimen in their clay pit near Swindon, Wiltshire, from the Upper Jurassic Kimmeridge Clay. He contacted Richard Owen at the British Museum, who sent William Davies to collect it. The fossil was encased in a nodule that was 8 feet high. When they tried to lift it, the clay crumbled into pieces, so they had to crate each piece separately. When the pieces were finally shipped to London, they weighed 3 metric tonnes (7 tons), and it took two years for Owen’s preparator, Caleb Barlow, to extract it and put it all back together. Additional fragments of a stegosaur similar to this were found in other British Jurassic beds throughout the rest of the 1800s. Owen finally described it in 1875 and named it Omosaurus armatus. Unfortunately, that name had already been used for a phytosaur, Omosaurus perplexus, by Joseph Leidy in 1856, so it was unavailable. In 1902, American paleontologist Frederick A. Lucas realized the problem and gave it a new generic name, Dacentrurus (“very pointed tail” in Greek). Since then, stegosaur fossils all over England, France, Spain, and Portugal have been referred to Dacentrurus, although they are mostly fragments and the complete skeleton is still unknown. Modern analysis has determined that Dacentrurus is a very advanced stegosaur, related to the Portuguese genus Miragaia and to the American Stegosaurus and not to the dozens of other more primitive stegosaurs.

In the early days of paleontology, most of the fragmentary European specimens of stegosaurs were by default assigned to the well-known American genus Stegosaurus. Some of these fragments from Middle Jurassic rocks in England and France were named Stegosaurus priscus in 1911 by one of the most colorful characters in the history of paleontology, Baron Franz Nopcsa (pronounced “nop-cha”). That material was eventually moved from Stegosaurus, then assigned to Lexovisaurus, and finally renamed Loricatosaurus by Suzanne Maidment and colleagues in 2008. But Nopcsa deserves more than a passing mention here.

Born in Transylvania (then part of Austria-Hungary) on May 3, 1877, to an aristocratic Magyar and Romanian family, Baron Franz Nopcsa von Felsö-Szilvás was easily one of the most bizarre and interesting characters, not just in paleontology but in all of science.

Baron Nopcsa was a notorious figure in his day. A wild genius with a flair for the dandyish and the dramatic, he was an explorer, spy, polyglot and master of disguise. He crossed the Albanian Alps on foot and befriended local mountain men, sometimes involving himself in their tribal feuds. Once, he was nearly crowned King of Albania. It was said that he would disappear for months at a time only to arrive for polite tea at posh European hotels dressed as a peasant. Along with a younger man whom he called his secretary, he traversed swaths of the Balkans on motorcycle. He kept up years-long correspondences with famous and learned men all across Europe. Later in his life, he was known for chasing villagers from his estate with a pistol. (Vanessa Veselka)

Steve Brusatte adds to this description:

He seems like the invention of a mad novelist, a character so outlandish, so ridiculous, that he must be a trick of fiction. But he was very real—a flamboyant dandy and a tragic genius, whose exploits hunting dinosaurs in Transylvania were brief respites from the insanity of the rest of his life. Dracula, in all seriousness, had nothing on the Dinosaur Baron.

Nopcsa got an early start when his younger sister, Ilona, found dinosaur bones on their family estate in Transylvania.

Nopcsa was born to a wealthy noble family, the eldest of three children raised at Sacel. He had a typical upbringing for an aristocrat in a provincial backwater of an aging empire. At home he spoke Hungarian and learned Romanian, English, German and French. His father, Alexius, had fought in Mexico against Benito Juárez, in 1867, as a hussar in the army of Maximilian, Archduke of Austria and Emperor of Mexico. Later Alexius became a vice-director at the Hungarian Royal Opera, in Budapest. Nopcsa’s mother, Matilde, came from an aristocratic family from the nearby city of Arad.

In 1895, Nopcsa’s sister Ilona was walking along a riverbank near the family home when she found an unusual-looking skull, and she brought it to her teenaged brother. It soon became his obsession. The skull belonged to a previously undiscovered duck-billed herbivore from the dusk of the Mesozoic…. Crushed by geological forces, the skull was in terrible shape. In the fall, Nopcsa entered the University of Vienna and took the skull with him. Like a cat with a gift rat, he presented it to his professor, a famous geologist, expecting him to take it from there. But the professor sent Nopcsa back to Transylvania and told him to figure it out for himself. Whether it was lack of interest or funding or the cunning strategy of a master teacher, it was the making of a great scientist. (Vanessa Veselka)

Inspired to study fossil bones, Nopcsa was largely self-taught, but he received his formal education at the University of Vienna, where he was already giving lectures by age 22. He spent much of his life studying and publishing on the geology and the dinosaurs of Europe, particularly of his home area in Transylvania. His writings on the geology of the Balkans were full of theoretical ideas in tectonics that fit the soon-to-be-proposed theory of continental drift of Alfred Wegener.

His dinosaurian discoveries were impressive. These included the pygmy sauropod Magyarosaurus (only 6 meters long rather than 30 meters like elsewhere), the duckbill Telmatosaurus transylvanicus, the primitive ornithopod Zalmoxes robustus, another species of indeterminate theropod referred to as Megalosaurus, the small nodosaurid ankylosaur Struthiosaurus transylvanicus, and the English ankylosaur Polacanthus ponderosus, which he named. He also described some of the first dinosaur eggs found anywhere, long before the American Museum found dinosaur eggs in Mongolia in 1923. The small body size of many of his Hungarian and Romanian dinosaurs from the Hateg Basin suggested to him that they had once lived on islands in a Cretaceous seaway. Similar to Ice Age pygmy elephants and hippos on Mediterranean islands, these dinosaurs apparently become dwarfed due to the small food resource base of the island and because they no longer needed large body size to cope with predators. Nopcsa was one of the first to develop the theoretical basis for island dwarfism.

Nopcsa’s most important pioneering contribution to paleontology was what he called “paleophysiology”: the idea of thinking about extinct fossils as complete living breathing animals rather than just a collection of dead bones, as most other scientists did at that time. Nopcsa was one of the first to argue that birds evolved from ground-dwelling dinosaurs and that they developed feathers to aid in running, two ideas that wouldn’t be popular until the 1970s. His research on jaw mechanics in dinosaurs was 60 years ahead of his time. He also looked at the great diversity of crests on duck-billed dinosaurs and imagined that the ones with crests were males, and the ones without were females of the same species (as is typical in horns of antelopes or antlers of deer today). He thought Kritosaurus was a female of Parasaurolophus, Prosaurolophus the female of Saurolophus, and many other combinations. Most of these dinosaurs have since been proven to be distinct genera, but sexual dimorphism has been claimed in duckbills like Lambeosaurus.

Nopcsa also had another obsession: independence for the tiny province of Albania, which was on the border between the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Turkish Ottoman Empire. Even though he came from Transylvania, Nopcsa taught himself the Albanian language, learned their folklore and history, and published over 50 scholarly studies on the region. He spent a lot of time in Albania learning about the people and developing good relations with the local leaders. Stephanie Paine wrote this about his exploits:

At the crack of dawn, Franz Nopcsa mounted his horse and set off for Shkodra, one of the most ancient towns in Albania. It was 1903 and the young aristocrat from Transylvania had just finished his PhD, a meticulous study of dinosaur remains dug up on his family estate. Now he was exploring a place he had dreamed about since childhood—the wild, romantic mountains of northern Albania, a land peopled by lawless tribes who were well-armed and very dangerous. As Nopcsa approached a bend in the road, there was a shot. “The bullet went right through my hat and grazed my head, but did not injure me,” he wrote later. “I leapt off my horse and sought shelter.” But when he tried to fire back, his assailant had vanished. The rest of the journey, he wrote with some disappointment, “passed without event.” Not much of Nopcsa’s life passed without event.

Eventually, Nopcsa became a revolutionary, giving fiery speeches and smuggling weapons into the country to aid the revolt against the Turks. In 1912, the entire Balkan region rose up in rebellion and drove out the Turks, and Albania became independent. With his background in Albanian culture and aristocratic roots, Nopcsa thought he should be considered as a candidate to be the first king of Albania, an idea he continually tried to promote. This idea was not so far-fetched. The Austro-Hungarian government could support any suitable nobleman, but they ended up picking a German aristocrat instead of Nopcsa.

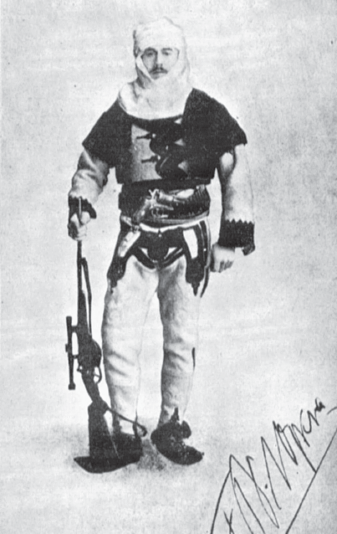

There are several dramatic portraits of Nopcsa in Albanian warrior garb (figure 20.3). In his diary, he wrote: “Once a reigning European monarch, I would have no difficulty coming up with the further funds needed by marrying a wealthy American heiress aspiring to royalty, a step which under other circumstances I would have been loath to take.”

Figure 20.3

Baron Franz Nopcsa in the Albanian shqiptar warrior costume, about 1913. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Unfortunately, his plans were derailed by the outbreak of World War I. As a rich, educated, multilingual Austro-Hungarian aristocrat, he served as a spy for their empire under the guise of traveling to do scientific research. He even organized and led his own corps of Albanian volunteers in the war. But when the war ended and the Central Powers (Germany, Turkey, and Austria-Hungary) lost, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was broken up into smaller countries. Nopcsa’s Transylvania became part of Romania, and he lost all of his ancestral estates and most of his wealth. He took a job at the Hungarian Geological Institute to pay his bills, but this didn’t work due to his abrasive personality. Eventually he moved to Vienna to study the fossils he had collected. Accompanying him was his young Albanian secretary and lover for almost 30 years, Bajazid Elma Doda. Many people knew that Nopcsa was gay (a dangerous thing to admit back then). Together they would ride his motorcycle all over Europe, Doda riding in the sidecar.

In Vienna, however, his financial difficulties distracted him from his work, and he slipped into a deep depression. Finally, he was forced to sell all his fossil collections to the British Museum to cover his debts, which depressed him even further. By 1933, at the bottom of this manic-depressive roller coaster, he drugged Doda’s tea with a sedative, took a gun and shot his lover in the head, then killed himself.

As Gareth Dyke wrote, Nopcsa’s “theories about dinosaur evolution turn out to have been decades ahead of their time…. Only in the past few years, with new fossil discoveries, have scientists begun to appreciate how right he was.” Reading through his writings, he was clearly a brilliant scientist and Albanologist, but he was also insensitive and unable to understand the motives of others and had a sociopathic personality. Whether this was due to some sort of psychological problem (many people think he was manic-depressive, and possibly autistic) or was mainly caused by his aristocratic arrogance, is still debated by scholars. Nopcsa was a brilliant paleontologist who pioneered paleobiology, almost became the king of Albania, and was openly gay. He was a very complex, interesting man, to say the least.

THE PALEOBIOLOGY OF STEGOSAURS

Even with a century of familiarity, Stegosaurus is still a very weirdly constructed animal. The head was very low to the ground, forcing stegosaurs to eat mostly low-growing brushy vegetation. In the Jurassic and Early Cretaceous, this would have been mostly ferns and cycads (sego palms), along with mosses, horsetails, and short conifers; grasses and abundant flowering plants did not appear until much later in the Cretaceous. The long narrow skull had a pointed snout without teeth, probably covered by a horny beak like that of a turtle. The cheek teeth were small, flat, and triangular, with wear facets showing some evidence of grinding their food. The most complete specimens show that the throat region was protected by a “chain mail” of tiny bony plates called osteoderms.

Famously, Stegosaurus had a small brain, about 80 grams (20.8 ounces), about the size of the brain of a dog, which is tiny considering their huge body mass of 4.5 metric tonnes (5 tons). Scaling brain to body mass, Stegosaurus has one of the smallest brains proportional to its size of any dinosaur known. One of Marsh’s fossil skulls had a well-preserved brain cavity, allowing him to make a cast of the cavity and describe the brain features in the 1880s. This led to the famous myth that its brain was so small that Stegosaurus needed a second brain in its hips just to function (satirized in the poem at the beginning of this chapter). In reality, the “second brain” was just a slightly enlarged ganglion of the nervous system, which would have controlled the muscles in the back of the body; it was not a true brain. It’s also likely that most of the space housed a glycogen body (also found in sauropods). This feature is typical in living birds and supplements the supply of glycogen (a sugar) to the nervous system. Stegosaurus did not need much intelligence to continually munch away at ferns and low-growing vegetation. Its spiked tail and other defenses and huge size seem to have been sufficient for its needs; stegosaurs were very successful for millions of years and spread worldwide.

The body of stegosaurs was weirdly proportioned, with short forelimbs and long hind limbs. This forced the spine into a big arch that flexed upward over the hips but sloped down steeply to the head and tail (see figure 20.2C). Each hand and foot had three short toes, each of which bore a hoof. In most stegosaurs, the hands had only two finger bones in each finger, and two toe bones in each toe.

The most famous feature of Stegosaurus was the huge flat plates over their entire back. The plates were not attached to the spine by a direct bony connection but held in place with cartilage, tendons, and muscles. Originally, Marsh thought that the plates laid flat on the side of Stegosaurus, like shingles or tiles, but later specimens proved that idea was wrong. In his 1891 reconstruction (see figure 20.2C), Marsh thought the plates formed a single line down the middle of the back, but this idea was discarded once more plates were found. For many years, a number of reconstructions showed the plates paired with each other down the middle of the back. Today you can still find illustrations and toys with this configuration. (It was the version used in the movie King Kong.) But the famous “road kill” type specimen of S. stenops (see figure 20.2A–B) clearly showed that the plates were alternating in two rows down the back, and several other recent discoveries have confirmed that arrangement.

What the plates were used for has long been debated. Originally, Marsh and other early paleontologists thought they were protective, although the plates didn’t do much of job of shielding their sides or flanks from attack by a theropod such as Allosaurus (both are found together in many Morrison localities). Some people thought the plates were not adaptive at all. For example, Frederic Loomis argued that the plates adorning the backs of stegosaurs were maladaptive traits that sapped their vigor and signaled their impending extinction.

More recently, a consensus has formed that they were probably for species recognition and advertising their age and status. Most scientists think that males and females of Stegosaurus both appear to have the same sized plates, so it’s not a sexually dimorphic feature in that genus. But a study published in 2015 claimed that the plates were different in males and females, with wider plates in males and taller plates in females. The questionable Morrison genus Hesperosaurus might have evidence of different male and female plates.

In the 1970s, John Ostrom’s former student Jim Farlow did a series of slices through the plates and found they had large cavities and big canals for a lot of blood vessels. Coupled with the other ideas brewing during the Dinosaur Renaissance and the warm-blooded dinosaur debate, this suggested that the plates were for picking up or shedding excess body heat. However, no other group of dinosaurs seemed to need these structures to regulate body temperature. Most other stegosaurs simply have conical spikes or deeply embedded armor plates, so the function of heat regulation would be unique to Stegosaurus and not found in any of its close relatives.

In addition, some paleontologists have argued that the bony plates were covered with keratinous horny sheaths to increase their size—but this also would have reduced any heat transport through the outside of the plate to the blood beneath. The surface of the plates, however, were covered by bony grooves for blood vessels, so any horny sheath would have covered and protected these. The horny sheath would have reinforced not only a defensive function but also improved their use as display structures. Like most arguments over the function of unusual structures in extinct animals, we may never know the truth. In addition, there is often no simple “right” answer; it’s likely that these structures performed more than one function.

The other distinctive feature of Stegosaurus is its spiky tail. Some paleontologists argued that these were just for display, although most have regarded them as defensive weapons. Many of the early reconstructions showed Stegosaurus with six to eight spikes, but a more careful analysis shows they had only four. Any model or reconstruction with more than four is in error. Contrary to many reconstructions, the four tail spikes did not point upward. They stuck out upward and sideways away from the tail axis, making them much more effective as a weapon with a side-to-side striking motion. Their tails were not held rigid like most dinosaur tails, so they could swing it around. However, the rows of plates on the upper part of the tail restricted movement to some degree. The most important evidence about the tail as a weapon was published in 2001 by McWhinney and colleagues and showed that the spikes had a very high incidence of damage (9.8 percent of specimens examined), suggesting they were used in defense to strike hard objects. In addition, an Allosaurus tail vertebra had puncture marks that fit the tail spikes of Stegosaurus perfectly.

The tail spikes had no formal anatomical name until cartoonist Gary Larson published a “Far Side” cartoon showing cave men watching a slide show. The lecturer points to the tail of a Stegosaurus and says, “Now this end is called the thagomizer…after the late Thag Simmons.” “Far Side” cartoons were always hugely popular with scientists because they often talked about scientific topics or were based on scientific in jokes. The term thagomizer entered the scientific lexicon when Ken Carpenter used it in a lecture at the 1993 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting. Since then, it has been picked up in numerous dinosaur books, used in the displays at Dinosaur National Monument, and in the BBC series Planet Dinosaur. Although there is no formal procedure for making popular nicknames into official anatomical terms, thagomizer is widely used in paleontology, usually with a smile and a chuckle the first time it is mentioned.

Of course, Larson knowingly committed a scientific boo-boo when he showed “cave men” living with dinosaurs, but Larson was fully aware of this, and it was necessary for the joke. Larson has written that “there should be cartoon confessionals where we could go and say things like, ‘Father, I have sinned—I have drawn dinosaurs and hominids in the same cartoon.’” A similar anachronism that is usually overlooked is the common pairing of Stegosaurus with Tyrannosaurus rex, found in many books and cartoons and in the animatronic dinosaurs of “Primeval World” in Disneyland. In reality, Stegosaurus vanished about 140 million years ago (Late Jurassic), yet T. rex did not appear until 68 million years ago (latest Cretaceous). It’s staggering to think about it, but T. rex is closer in time to humans than it is to Stegosaurus.

THE RISE AND FALL OF STEGOSAURS

Two of the earliest stegosaurs to be described were Regnosaurus from Britain and Dacentrurus from western Europe—both before Stegosaurus itself was named in 1877. As the years went by, more and more different kinds of stegosaurs were found, nearly all with completely different configurations of armor, plates, and spikes.

One of the first stegosaurs to be discovered was the spiky African genus Kentrosaurus aethiopicus (figure 20.4) from the Tendaguru bone beds in what is now Tanzania (see chapter 9). It was named by Edwin Hennig in 1915, and its name means “sharp point lizard” in Greek. Kentrosaurus is known from hundreds of bones found in multiple quarries between 1910 and 1912 (although many were lost during the bombing of German museums in World War II). It was about 4.5 meters (15 feet) long and weighed about 1 metric tonne (1.1 tons), considerably smaller than some Stegosaurus, which reached up to 9 meters (30 feet) in length, and 5.3–7 metric tonnes (6–7.5 tons) in weight. In most respects, Kentrosaurus is much like Stegosaurus, with a small but long and narrow head, toothless beak, short front limbs and long hind limbs, and a relatively long tail. Unlike Stegosaurus, however, it had small plates only on the front half of its backbone, and most of the rest of the spine was covered with paired spikes that clearly served a defensive function.

Figure 20.4

The Late Jurassic spiky stegosaur Kentrosaurus, from the Tendaguru beds of Tanzania. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

For a while, the name Kentrosaurus was also questioned because the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature forbids names that sound the same (homonyms), and there is also a ceratopsian named Centrosaurus. Some scientists recommended that Hennig’s 1916 replacement name, Kentrurosaurus, be resurrected, and the name Doryphorosaurus was contributed by Nopcsa in 1916. However, the Kentrosaurus and Centrosaurus are not really homonyms because Kentrosaurus is pronounced with the hard “K” sound whereas Centrosaurus is pronounced with the soft “C” (as in “center”), so there is no real confusion and no need to drop the name Kentrosaurus.

We have discussed the abundant American, European, and African stegosaurs, but their range also extended to China. These amazing fossils had been unknown to Westerners during the political turmoil of the mid-twentieth century, but they finally began to be available for study after the war. The first of these was Chialingosaurus, from the Middle Jurassic of China, found during the war years in the 1930s and 1940s and finally named in 1959 by Yang Zhongjian (also written C.C. Young), the “Father of Chinese Paleontology.” Chialingosaurus is based on a partial skeleton, and some do not consider it to be a valid genus for that reason. However, it apparently had small plates in pairs along its neck and backbone along the shoulders, and paired spikes down the rest of its back and tail, like Kentrosaurus.

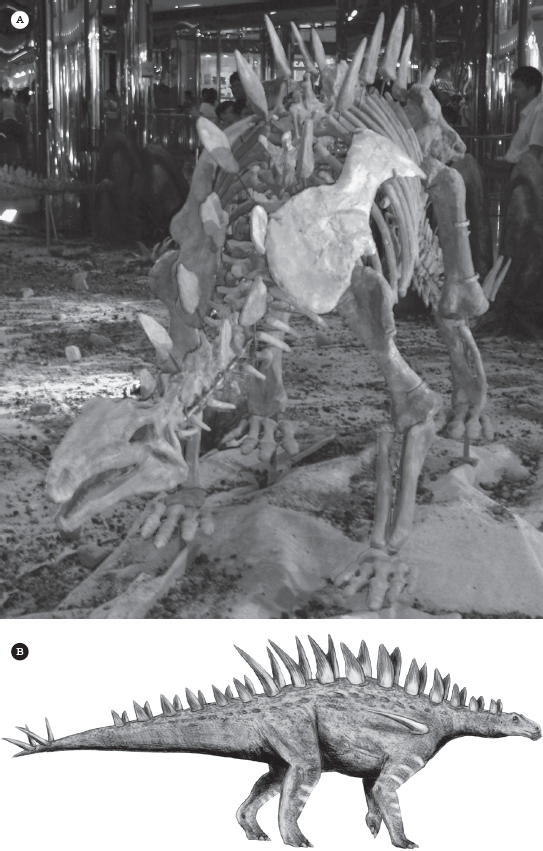

In 1973, Dong Zhiming (currently the dean of Chinese dinosaur specialists) named Wuerhosaurus from the Early Cretaceous of China and Mongolia, one of the very last stegosaurs known. It also consists of a fragmentary skeleton, plus parts of a few more individuals. Its body was much fatter and broader than other stegosaurs, based on the broad pelvis. At one time, it was argued that it had very rounded plates in rows on its back, but this has been dismissed as an artifact of breakage of the few plates found. Dong and others described Huayangosaurus in 1982, based on a partial skeleton and some other specimens from Middle Jurassic beds of China (figure 20.5). Unlike other stegosaurs, the plates down its back are tall narrow triangles rather than broad polygons. It also had a Thagomizer of four spikes at the tip of its tail.

Figure 20.5

(A) The Middle Jurassic Chinese stegosaur Huayangosaurus, with a combination of spikes and narrow triangular plates on its back. (B) Restoration of the dinosaur in life. ([A] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [B] courtesy of N. Tamura)

Its close relative is the Upper Jurassic stegosaur Chungkingosaurus, named and described by Dong and others in 1983. Chungkingosaurus had an arrangement of tall, narrow plates on its back and spikes on its tail similar to that of Huayangosaurus. Another Late Jurassic stegosaur with similar armor is Tuojiangosaurus, described by Dong and colleagues in 1977. It may be closely related to Paranthodon from Africa. There is also Gigantospinosaurus from the Late Jurassic of Sichuan, which had huge spikes protruding from it shoulders, and Jiangjunosaurus, based on a fragmentary skeleton from the Late Jurassic of Inner Mongolia. That makes at least six Middle Jurassic to Early Cretaceous stegosaurs from China and Mongolia, giving it the highest stegosaur diversity in the world, with almost two dozen additional genera in Eurasia, Africa, and North America.

But what about the rest of the Pangea continents: Australia, India, Antarctica, Madagascar, and South America? So far none of them have produced unquestioned stegosaurs, although the fossil record in Australia, Madagascar, India, and, of course, Antarctica is relatively poor during their heyday in the Middle and Late Jurassic. Dravidosaurus from the Late Cretaceous of India turned out not to be a stegosaur. In one interpretation, it was based on a weathered set of plesiosaur hip bones and hind limbs. Later authors, however, ruled out the plesiosaur interpretation, concluding that the specimens are too incomplete to tell what they really are. Trackways have been found in Australia that are claimed to be stegosaurian, but so far no bones have come to light.

In 2017, Leonardo Salgado and colleagues described a skull fragment and partial skeleton from the Early Jurassic of Patagonia. The specimen even had gut contents showing that it ate cycads. Named Isaberrysaura mollensis, it is definitely an advanced ornithischian, and that is the only commitment Salgado and coauthors would make. However, based on the stegosaur-like characteristics in what is known of the skull, another analysis of it suggested that it might be a very primitive bipedal relative of the stegosaurs.

We have an amazing record of stegosaurs from most of the Jurassic and Early Cretaceous. Along with the possibility that Isaberrysaura may be an Early Jurassic stegosaur, stegosaurs are definitely known from the Middle Jurassic, when they evolved from scelidosaurs, their common ancestor with the ankylosaurs. Together, the stegosaurs, scelidosaurus, and ankylosaurs form a group now called the Thyreophora (“armor bearing” in Greek).

The earliest known undoubted stegosaur is Huayangosaurus from the early Middle Jurassic of China; followed by late Middle Jurassic stegosaurs such as Chungkingosaurus, Chialingosaurus, Tuojiangosaurus, and Gigantospinosaurus from China; and Lexovisaurus and Loricatosaurus from England and France. In the Late Jurassic, stegosaurs were in their heyday in abundance and size, if not diversity, with Kentrosaurus in Africa, Dacentrurus and Miragaia in Europe, Jiangjunosaurus in China, and Stegosaurus and Hesperosaurus in North America.

By the Early Cretaceous, stegosaurs experienced their last phase of evolution, with Wuerhosaurus in China, Paranthodon in Africa, and Craterosaurus from England, plus some undescribed fragments from Russia. Paleontologists have long speculated on what caused the decline and extinction of stegosaurs. Certainly the vegetation was changing, with the decline of cycads (possibly their main food source) paralleling the decline in stegosaurs. In addition, by the Early Cretaceous there was a tremendous bloom of flowering plants, including many types of water plants and primitive trees such as magnolias. Many paleontologists have suggested that the rapidly reproducing flowering plants may have stimulated the evolution of duck-billed dinosaurs with their complex “dental batteries” of hundreds of prismatic teeth fused together. They were clearly more specialized and efficient plant eaters than the almost toothless stegosaurs, and it is possible that they co-evolved with flowering plants to dominate the Cretaceous landscape. The stegosaurs were Jurassic relicts and apparently did not do well when facing new competition from herbivores, changing plants in their diet, and possibly new predators as well. For whatever reason, stegosaurs vanished by the end of the Early Cretaceous.

FOR FURTHER READING

Brinkman, Paul D. The Second Jurassic Dinosaur Rush: Museums and Paleontology in America at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Carpenter, Kenneth, ed. Armored Dinosaurs. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001.

Colbert, Edwin. Men and Dinosaurs: The Search in the Field and in the Laboratory. New York: Dutton, 1968.

Farlow, James, and M. K. Brett-Surman. The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999.

Fastovsky, David, and David Weishampel. Dinosaurs: A Concise Natural History, 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Galton, Peter M. “Stegosauria.” In Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs, ed. Philip J. Currie and Kevin Padian, 701–703. San Diego: Academic Press, 1997.

Galton, Peter M., and Paul Upchurch. “Stegosauria.” In The Dinosauria, 2nd ed., ed. David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, and Halszka Osmólska, 343–362. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Holtz, Thomas R., Jr. Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. New York: Random House, 2011.

Naish, Darren. The Great Dinosaur Discoveries. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Naish, Darren, and Paul M. Barrett. Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 2016.

Spaulding, David A. E. Dinosaur Hunters: Eccentric Amateurs and Obsessed Professionals. Rocklin, Calif.: Prima, 1993.

Veselka, Vanessa. “History Forgot This Rogue Aristocrat Who Discovered Dinosaurs and Died Penniless.” Smithsonian Magazine, July 2016. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/history-forgot-rogue-aristocrat-discovered-dinosaurs-died-penniless-180959504/.