The frontal and parietal have become so firmly coalesced that there is no remaining indication of a sutural contact between them. The development of these two bones into a very much enlarged dome-like mass is the most striking single feature of the skull. So extreme is the vaulting in this area that more than 6 inches of solid bone lie above the portion of the endocranial cavity that was occupied by the olfactory stock of the brain and 9 inches above the region of the cerebellum. In no other reptile has the skull roof become so thickened…. Most of the mass is composed of a compact fibrous structure made up of many small columns of bone which radiate out from a thin dense ventral zone and terminate in an equally dense outer zone. The outer surface is without ornamentation and presents numerous perforations leading to canals which penetrate into the fibrous zone.

—BARNUM BROWN AND ERICH M. SCHLAIKJER, “A STUDY OF THE TROÖDONT DINOSAURS WITH THE DESCRIPTION OF A NEW GENUS AND FOUR NEW SPECIES,” 1943

LAWRENCE LAMBE AND THE “UNICORN DINOSAUR”

The early work in western Canada by Americans such as Barnum Brown and the Sternbergs has been discussed, but the “Father of Canadian Dinosaur Paleontology” was Lawrence Lambe. Born in 1863, he was just slightly younger than the pioneering generation of Cope and Marsh, but he was close in age to the “next generation” of paleontologists such as Osborn, Scott, Matthew, and Granger. Unlike Tyrrell and Weston, the first men into the Red Deer River badlands who were geologists doing a survey and mapping project, Lambe had some training in paleontology.

Born in Montreal, Lambe originally planned a military career, and he graduated from the Royal Military College in Kingston, Ontario, ready to become an Army officer. As he waited for his first commission, he was assigned to be an assistant construction engineer on the Canadian Pacific Railroad, which was blazing a trail across the Rocky Mountains and giving Canada its first transcontinental railroad. While working out there, he contracted typhoid fever, which was typically fatal in those days. He recovered but had to give up on an Army career because his health was impaired. He was already a talented artist, and he took a position in the Geological Survey of Canada in 1885, drawing fossils under the supervision of paleontologist J. F. Whiteaves. Soon he was not only doing drawings but also doing research in fossil corals, picking up the fundamentals of paleontology as he worked. Nearly all of his generation of paleontologists were self-taught because there were no college courses in paleontology. Most got a background in either anatomy or geology, then they learn paleontology by doing it.

Lambe had an opportunity to return to western Canada in 1897. The government was conducting test boring in northern Alberta, and they needed a geologist from the Geological Survey of Canada on the site. Soon he was running his own boat trip down the Red Deer River, following the tracks of Weston. He did a quick reconnaissance of the badlands over the course of a month, drifting down to the Saskatchewan Landing on the South Saskatchewan River. The next year he brought a crew with horse and wagon all the way from Medicine Hat to the site of Steveville, where he focused on collecting in the Berry Creek area (figure 23.1) because his camp was not down on the river level in the bottom of the canyon. In the 1898 and 1899 field seasons, he collected theropods, duckbills, and horned dinosaurs, as well as lots of turtles and crocodiles. However, he was just learning to collect in the field and did not know about the careful excavation techniques, the use of hardeners to hold specimens together, or plaster jackets to protect them during shipping that American paleontologists were pioneering, so most of what he brought home was pretty fragmentary.

Figure 23.1

Lawrence Lambe and his assistant in camp near the Red Deer River, Alberta, 1901. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

After two field seasons, he had a lot of specimens that he needed to compare to other known fossils. He spent a number of weeks at the American Museum as a guest of Henry Fairfield Osborn, who took and interest in his work and offered to collaborate. Here Lambe learned of the latest in dinosaur paleontology, saw the best specimens in the United States, and quickly made up for his lack of training in field collection and preparation methods. Lambe returned the favor by helping appoint Osborn the Honorary Vertebrate Palaeontologist for the Geological Survey of Canada. Lambe mounted one more collecting season in 1901 to explore the badlands downstream from Berry Creek, but his best collection was made in his last weeks on the Red Deer River.

In 1902, Osborn and Lambe published the first paleontological monograph on the specimens from the Red Deer badlands, On Vertebrata of the Mid-Cretaceous of the North West Territory. It was beautifully illustrated by Lambe himself and laid the foundation for all the future dinosaur studies in the region. In this volume, Osborn established that these fossils and the beds that produced them were definitely earlier in the Cretaceous than the specimens from the Hell Creek and Lance formations in Wyoming and Montana. Unfortunately, many of Lambe’s specimens were fragmentary, and it was often hard to interpret what they were. Later work by Brown and the Sternbergs recovered much better fossils, which made Lambe’s broken type specimens hard to use.

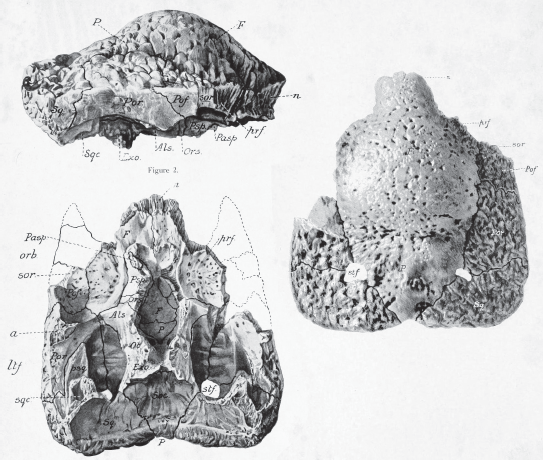

During the 1898 field season, Lambe had collected two strange lumps of solid bone that were very puzzling. There was a smooth dome on the top of the specimen and spongy bone all around the broken sides of the skull (figure 23.2), but it was hard to tell what kind of animal had produced this fossil because no other parts were preserved. Nevertheless, in a short paper in 1902, he named the fossils Stegoceras validum. Stegos means “roof” and ceras means “horn” in Greek, so it was the “horn-roofed” dinosaur; the species name validum means “strong,” in reference to the thickness of the skull roof. Lambe did the best he could with interpretations of the specimens, but it wasn’t even clear what part of the skull the small domes had come from. He thought it came from the snout of a large dinosaur, like the short horns on the nose of Triceratops. In 1903, Baron Franz Nopcsa published a different interpretation, arguing that it was a blunt horn on the forehead of the dinosaur, possibly between the eyes. In 1903, Lambe endorsed Nopcsa’s suggestion, calling it a “unicorn dinosaur.”

Figure 23.2

Lambe’s original illustration of the bony dome of Stegoceras, showing the broken spongy bone around the edges and the top of the braincase exposed on the bottom of the bony dome. (From Osborn and Lambe, 1902)

Paleontologists were puzzled not only about what the complete skull of this fossil might have looked like but also whether this fossil was a weird kind of ceratopsian, or an even weirder kind of stegosaur. In 1907, the ceratopsian expert John Bell Hatcher (see chapter 25) weighed in on the fossils. He doubted whether the two specimens were from the same species, and whether they were even from dinosaurs at all. However, he did correctly suggest that they came from the top of the skull, from the frontal bones above the eyes to the parietal bones in the back of the skull. In 1918, Lambe added another dome fossil to the collection of Stegoceras and decided it was a member of the group that included stegosaurs and ankylosaurs, which he called the Psalisauridae (now called the Thyreophora).

This was his last paper on the mystery fossils; Lambe died at the relatively young age of 56 in 1919. The Father of Canadian Dinosaur Paleontology had named not only Stegoceras but also a slew of important Cretaceous dinosaurs, including the ceratopsians Centrosaurus, Chasmosaurus, Styracosaurus, and Eoceratops; the theropod Gorgosaurus; the ankylosaurs Euoplocephalus and Panoplosaurus; the duckbills Gryposaurus and Edmontosaurus; as well as crocodilians, such as Leidysuchus, and several turtles. After his death, Canadian paleontologist W. A. Parks named the crested hadrosaur Lambeosaurus in his honor.

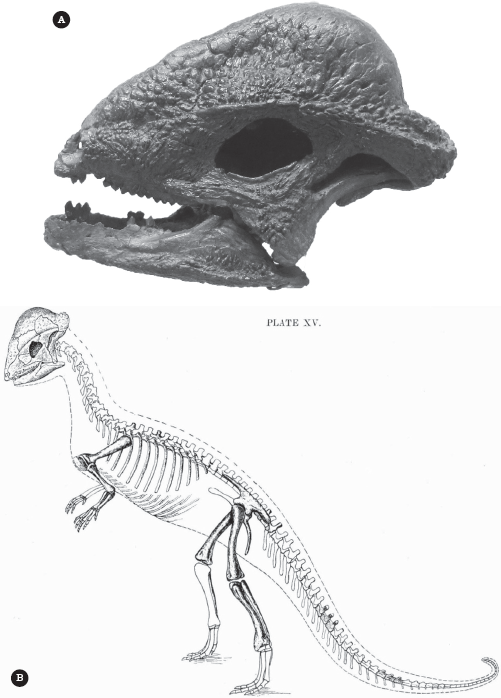

The breakthrough in understanding Stegoceras came in 1924 when a complete, unbroken skull and jaws and partial skeleton was found by George F. Sternberg and acquired by the University of Alberta. It was described by Smithsonian dinosaur expert Charles W. Gilmore (figure 23.3). The complete skull (figure 23.3A) not only proved that Lambe’s bony dome sat on top of the head from the eyes to the back of the skull but also showed many other interesting features. It had large eyes, roofed by a shelf of bone protruding above them and below the dome of the skull. This ridge of bone continued to the back of the skull, producing a short “frill” over the neck that is found in all pachycephalosaurs and ceratopsians. This is one of many features that demonstrate that these two groups are close relatives, now known as the Marginocephalia. The entire frill around the back and side of the skull was covered with bumps and ridges of bones. The skull went from broad in the back to a short, narrow, pointed snout, with large forward-facing nostrils. CAT scans of the large olfactory bulbs of the brain showed that these dinosaurs had a good sense of smell. The jaw contained small leaf-shaped teeth, with a gap between the front teeth and the cheek tooth row. The front teeth were conical nipping teeth with a small set of ridges and cusps on them, and the cheek teeth were triangular in cross section.

Figure 23.3

Stegoceras: (A) complete unbroken skull and jaws, found by George F. Sternberg for the University of Alberta and published in 1924 by C. W. Gilmore; (B) Gilmore’s reconstruction of the entire animal, based on the skeletal elements found with the skull. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

The teeth of Stegoceras caused confusion for a long time. The front teeth were very similar to the teeth that Leidy had named Troodon in 1856, so initially Lambe’s Stegoceras validus was renamed Troodon validus. Later studies showed that the shape of the teeth was deceptive and that Troodon teeth better matched a group of small predatory dinosaurs. For a long time, all the early pachycephalosaurs were referred to Leidy’s genus, which confuses people who only associate the name with the small predator.

The partial skeleton of Stegoceras (figure 23.3B) is like that of many other small bipedal ornithischians, with no specialized armor or other features typical of the advanced groups such as stegosaurs, ceratopsians, or duckbills. Gilmore reconstructed some of the fossils he found as belly ribs, or gastralia, but they are now known to be the ossified trusswork of intermuscular bones in the tail. Like most other dinosaurs, Stegoceras held its tail straight out in the back. Because Stegoceras is known from a partial skeleton, it is one of the most completely known pachycephalosaurs because most others are known only from skulls. Stegoceras was about 2.0–2.5 meters (6.6–8.2 feet) long counting the long tail and weighed about 10–40 kilograms (22–88 pounds), about size of a goat. The front limbs were quite small, so the dinosaur was completely bipedal, unlike many larger ornithischians. The animal must have run in a bird-like fashion, with its tail stuck straight out behind it and the body balanced horizontally over the long hind limbs.

“THICK-HEADED LIZARD”

Stegoceras remained the only known pachycephalosaur until 1931 when a much larger skull with a thicker dome was found in the uppermost Cretaceous Lance Formation of Wyoming. Charles Gilmore described this larger genus as Troodon wyomingensis, thinking it was a larger version of Stegoceras (then mistakenly called Troodon). In 1943, Barnum Brown of the American Museum and Erich M. Schlaikjer from Harvard were collecting in the Hell Creek beds of the Ekalaka Hills in the southeast corner of Montana and found a beautiful skull of Gilmore’s “Troodon wyomingensis” (figure 23.4). They gave it the name Pachycephalosaurus, from the Greek words pachy meaning “thick,” cephalos meaning “head,” plus sauros for “lizard.” In 1945, Charles M. Sternberg realized that Leidy’s “Troodon” was based on teeth that mostly belonged to a small theropod and removed that name from the pachycephalosaurs. Since they were no longer in the Troodontidae, they were placed in a new family, the Pachycephalosauridae (although properly they should have been named the Stegoceratidae after the earliest valid genus in the group).

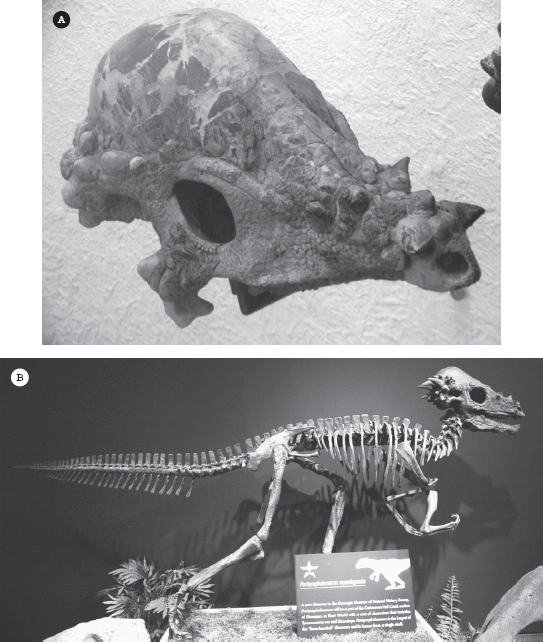

Figure 23.4

(A) The beautiful complete skull of the large genus Pachycephalosaurus, now on display at the American Museum of Natural History. (B) The skeleton of the Pachycephalosaurus nicknamed “Sandy,” now on display in the National Museum of Science and Nature in Tokyo. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Although no skeleton was known from the original specimens of Pachycephalosaurus, the skull is very impressive. The bulging dome on the skull was 25 centimeters (10 inches) thick and cushioned a tiny brain (the brain cavity is also preserved). All around the rear and sides of the dome are bony knobs, and there are bony spikes on the nose and snout. Like Stegoceras, it had large eyes covered by a rim of bone above the eye sockets. The snout was short, with a pointed beak. Pachycephalosaurus had tiny leaf-shaped teeth similar to those of others in the group.

The rest of the skeleton was unknown from the original skull fossils, but a partial skeleton has since been found in the Hell Creek Formation in South Dakota. Found by commercial collectors, it was sold to the National Museum of Science and Nature in Tokyo, where it was described by Taka Tsuihiji. Nicknamed “Sandy,” it was about 1.5 meters (5 feet) tall and 3 meters (10 feet) long. Its partial skull includes most of the back, side, and snout region, but not the dome. In addition, the fossil includes the hind limbs and hips, plus some neck and back vertebrae and ribs (figure 23.4B). Based on this specimen and other related pachycephalosaurs known from skeletons, Pachycephalosaurus was a medium-sized bipedal animal that weighed about 450 kilograms (990 pounds), had a fairly short, thick, S-shaped neck, very short forelimbs, a bulky body with a large gut for fermenting and digesting plants, long thick hind legs, and a heavy tail held out straight behind it by ossified tendons.

After 1943, the only known genera in the group for decades were Stegoceras and Pachycephalosaurus. Then, in the 1970s, the pace of discovery accelerated dramatically, and now more than two dozen genera are known. The first major discoveries came from the Polish-Mongolian expeditions of the 1960s and 1970s (see chapter 16). Polish paleontologists Teresa Maryańska and Halszka Osmólska published a major review of their finds in Mongolia. They propose a suborder Pachycephalosauria, and they added several new genera based on remarkable fossils found during the years of the expeditions. One of these was Homalocephale, which had a flat skull roof rather than the dome seen in other genera. Another genus was Prenocephale, which had a bulging dome and ridges of bone sloping down to a narrow snout, very much like Stegoceras but larger. Based on the proportions of the preserved bones, it was about 2.4 meters (8 feet) long. Some scientists argue that Homalocephale is just a juvenile version of Prenocephale that has not yet acquired the bulging dome-shaped forehead, but new finds have discredited this idea. A third genus is Tylocephale, which is known from a fragmentary skull that doesn’t preserve the dome or snout, represents an animal that may have been 1.4 meters (4.6 feet) long. Finally, Mongolian paleontologist Antangerel Perle and Maryańska and Osmólska published the genus Goyocephale in 1982. It consists of a partial skull and parts of the skeleton. The skull is much narrower than other genera, with a relatively flat top and no large dome, and it has lots of bony bumps on the back margin and all over the surface of the top of the skull roof.

I cannot mention all the other genera that have been described since 1974 here, but they have come from many different Cretaceous localities in North America and Asia. The most important to mention is the very primitive Wannanosaurus, from the early Late Cretaceous of China. It consists of only a partial skeleton, but it is more primitive than that found in any other pachycephalosaur. More important, the flat skull roof has almost no dome, and it still has the large openings in the sides and back of the skull found in most dinosaurs. Advanced pachycephalosaurs developed their thick bony domes and closed up these holes in the skull. Not only is it older and more primitive than the rest of the pachycephalosaurs, but it is one of the smallest dinosaurs known, with an estimated body length of only 60 centimeters (2 feet). This transitional fossil shows how the weird pachycephalosaurs evolved from much more primitive ancestors.

DINOSAUR RAMS?

The first people to describe Stegoceras and Pachycephalosaurus did not speculate much about how they behaved or the way the thick dome of bone was used. In 1955, Edwin Colbert was the first to suggest that the pachycephalosaurs were like dinosaurian rams, head butting with their heavily armored skulls. In addition to the solid helmet of bone, the shape of the neck suggested that they had strong neck muscles, with an S-shaped curve to absorb the shock of each blow. Others have suggested that they used their bony helmets to head butt the flanks of other members of their herd, giving a less lethal glancing blow. They had wide trunks and bellies, which would protect the internal organs from a head blow. One genus, Stygimoloch, had horns on the side of its face, which would have been even more effective in flank butting.

In 2004, Mark Goodwin and Jack Horner argued that pachycephalosaurs could not have endured direct head butting because the bone structure allegedly could not have absorbed such stresses. In their opinion, the dome was for species recognition only. This has been disputed by numerous analyses since then, which established that the spongy bone of the skull supporting the solid bone of the dome is indeed capable of absorbing head-to-head collisions. Their bone structure is much like that of rams and muskoxen, which also engage in head-to-head impacts. In addition, the domes do not appear to differ much among adults. Such differences between males and females would be expected if they were use for species recognition or mate recognition.

The battering ram model was further supported by a 2013 study of the pathologies of the specimens that had been injured. About 22 percent of the domes had damage or lesions consistent with osteomyelitis, a bone infection caused by penetrative trauma. The flat-skulled pachycephalosaurs show no such rate of injury, suggesting that they did not engage in head-to-head combat. This would make sense if they were females or juveniles who did not have to compete to become masters of their herds.

HORNY YOUNG DINOSAURS?

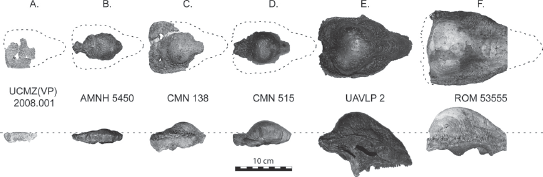

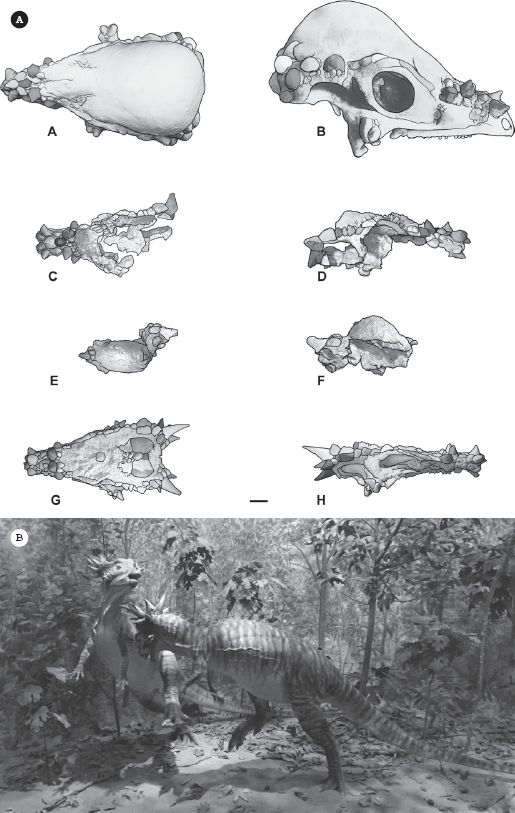

The variation in dome size also may be due to growth through time. There are enough different Stegoceras skulls known now to construct a growth series from juveniles to adults. Not only do the skulls get larger, but their domes go from flat to a slight bump to a large dome structure over the course of growth (figure 23.5).

Figure 23.5

Different specimens of Stegoceras interpreted as a growth series, with the small flat skulls considered to be juveniles, which grew into large domed forms as adults. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

The weird horned genus Stygimoloch spinifer was a great puzzle when it was first described. It got its name from the River Styx, the river at the entrance to Hades; Moloch was a Canaanite god who demanded child sacrifice; and “spinifer” means “spiny.” Then there was the even smaller horned genus Dracorex hogwartsi (dragon king of Hogwarts), which was described in 2006 as another small, horned adult pachycephalosaur. But several paleontologists have looked closely at these fossils and concluded that they were probably juveniles of the larger forms like Pachycephalosaurus that had not yet developed their dome but had relatively large spines (figure 23.6). The horns of all pachycephalosaurs seem to show a lot of developmental plasticity, with their shape and number and orientation changing within individuals of the same population as well as during their presumed growth. All of these dinosaurs came from the same Upper Cretaceous beds of Montana and Wyoming (except Stegoceras from Alberta, which has its own growth series). It makes sense that they might all represent growth stages of the same few genera that lived in that place and time. Of course, it’s impossible to know for sure from such a small sample of specimens, most of them fragmentary, which have no living descendants; so their behavior, growth features, and sexual differences cannot yet be determined.

Figure 23.6

(A) The small, spiky specimens of Stygimoloch and Dracorex were first described as different genera, but now some paleontologists view them as juvenile stages of Pachycephalosaurus. (B) Reconstruction of battling Stygimoloch in head-butting poses. ([A] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [B] photograph by the author)

PACHYCEPHALOSAURS THROUGH SPACE AND TIME

Pachycephalosaurs, like many groups we have just seen (especially tyrannosaurs, ceratopsians, most duckbills, and ankylosaurs), were a strictly Laurasian group from the Late Cretaceous and were never found anywhere else. (Specimens of Majungatholus from Madagascar and Yaverlandia from England are no longer considered pachycephalosaurs.) The oldest member of the group is Wannanosaurus from China, and it was the starting point of the first wave of migration in the early Campanian from Asia to North America, including such descendants as Stygimoloch, Stegoceras, Tylocephale, Prenocephale, and Pachycephalosaurus. The second migration from Asia occurred in the late Campanian, producing the lineage that led to Prenocephale and Tylocephale.

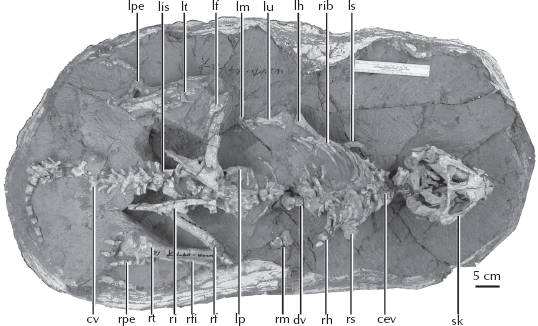

But where did pachycephalosaurs and other marginocephalans come from? In 2004, the most amazing fossil in this sequence was discovered with the description of Yinlong (figure 23.7) from much earlier Upper Jurassic beds of China. Its name means “hidden dragon” in Mandarin, a reference to the popular movie Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, part of which was filmed close to the locality where the fossil was found. Yinlong consists of a beautifully preserved skeleton of a bipedal dinosaur not too different in proportions from the primitive ceratopsian Psittacosaurus (see chapter 24). Yinlong has the rostral bone, a feature unique to ceratopsians, in its upper beak. However, its skull roof has a unique configuration of bones found in the pachycephalosaurs, which are famous for having a thick dome of bone in their skulls protecting their tiny brains. Paleontologists have long thought that ceratopsians and pachycephalosaurs are closest relatives, based on the fact that they both have a frill of bone around the back of the skull (hence their name, “Marginocephalia”). Like all marginocephalians (pachycephalosaurs plus ceratopsians), there is a frill in the back of the skull of Yinlong. But Yinlong shows features of both ceratopsians and pachycephalosaurs before their lineage split into the two families that every kid recognizes. Thus it forms a transition between more primitive ornithischians in the Jurassic and the most primitive pachycephalosaurs such as Wannanosaurus and the earliest ceratopsians such as Psittacosaurus.

Figure 23.7

The complete skeleton of Yinlong, a fossil from the Late Jurassic of China that appears to be the common ancestor of pachycephalosaurs and ceratopsians. It has the frill on the back of the head like both groups, and features such as the rostral bone are found in ceratopsians. (Courtesy of J. Clark)

FOR FURTHER READING

Brown, Barnum, and Erich M. Schlaikjer. “A Study of the Troödont Dinosaurs with the Description of a New Genus and Four New Species.” Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 82, no. 5 (1943): 115–150.

Colbert, Edwin. Men and Dinosaurs: The Search in the Field and in the Laboratory. New York: Dutton, 1968.

Farlow, James, and M. K. Brett-Surman. The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999.

Fastovsky, David, and David Weishampel. Dinosaurs: A Concise Natural History, 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Holtz, Thomas R., Jr. Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. New York: Random House, 2011.

Kielan-Jaworowska, Zofia. Hunting for Dinosaurs. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1969.

——. In Pursuit of Early Mammals. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013.

Maryańska, Teresa, Ralph E. Chapman, and David B. Weishampel. “Pachycephalosauria.” In The Dinosauria, 2nd ed., ed. David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, and Halszka Osmólska, 464–477. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Naish, Darren. The Great Dinosaur Discoveries. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Naish, Darren, and Paul M. Barrett. Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 2016.

Russell, Loris Shano. Dinosaur Hunting in Western Canada. Toronto, Canada: Life Sciences, Royal Ontario Museum, 1966.