Student services represents a significant investment of resources and personnel in any college or university. Beginning with enrolment and orientation to the institution, proceeding through accommodation services, guidance from various counselling and advisement offices, and engagement in campus leadership experiences, and concluding with arrangement of internship opportunities, job placements, and alumni connections, student services facilitates students’ entry, matriculation and, ultimately, success in the sometimes challenging world of post-secondary education. How are these services organized and funded? How are they best managed and led for student success? This chapter engages these questions through a conceptual frame and understanding based on experience and offers insights that bridge the historical and theoretical overviews of student services in Canada and the descriptions of its specific forms presented in the previous chapters.

This chapter is organized in four sections. It begins with an overview of how student services is organized at Canadian post-secondary institutions and the influences that have shaped it. Second is a discussion of the strategic processes that guide the leadership and management of student services, with particular emphasis on the role of the senior student services administrator in supporting student success. The third section highlights key issues that challenge the implementation and advancement of student services in Canadian higher education, and the chapter concludes with suggested resources essential to the professionalization of the field and the continued development of these services.

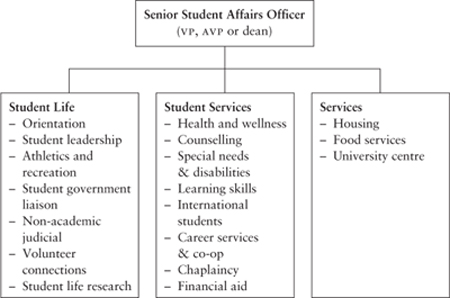

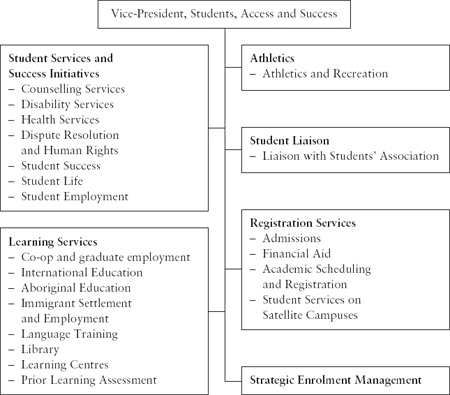

As reviewed in chapter 1, well-developed student services have existed for a significant period of time in Canadian post-secondary education, and today’s units are similar in function to those found in other countries (Sandeen 1996; UNESCO 2002). The Canadian Association of College and University Student Services (CACUSS) enumerated four categories of programs, services, and activities that constitute post-secondary student services: educational, supportive, regulatory, and responsive (Canadian Association of College and University Student Services). The key organizing considerations noted at the time were the extent to which student development was emphasized, along with whether the senior student affairs officer reported to the president or senior academic officer. To a degree, that observation now seems surprising, since the composition and organization of the student affairs portfolio was quite similar across institutions (See figure 1).

Figure 1

Organizational Chart for Typical Canadian Student Services Portfolio, (circa 1990)

Driving the prototypic organizational chart of that period was the fact that colleges and universities did not have residential populations and their student services organizations responded accordingly, although they more often had greater responsibilities for direct academic support programs, including student advising. Four developments since then have enlarged the scope of student affairs involvement and generated additional organizational options.

First, publication of the Student Learning Imperative (American College Personnel Association 1994) and Learning Reconsidered (Keeling 2004) has signalled the student affairs field’s renewed emphasis on student learning. Such documents have challenged student services to contribute to an institutional consideration of learning outcomes and determine its part in enabling students to achieve those ends. The development of over-arching learning objectives at the University of Guelph, and the response of its student services division with expanded academic readiness programs, peer-assisted learning groups, and formation of a learning commons, is one such example. Academic readiness evolved beyond remediation to assist all students, including the highest performing, in maximizing their post-secondary experience. Implementation of efforts focused on supporting and enhancing student learning has meant much more partnering with faculty and a deeper commitment to assessment. Such features have in turn influenced unit groupings and internal relationships within student services divisions. They have also been accompanied by increased professionalization and specialization of those staff involved in student learning efforts.

A second prominent change was the emergence of strategic enrolment management as a way of thinking about students, and institutional relationships as an organizing vehicle. To date, this has taken a softer form in Canada than in the United States because the system is public, the institutions are all more closely comparable (public, non-profit, comprehensive), articulation and transfer are largely standardized, adequate student demand has enabled institutions to meet financial targets, and the ranking frenzy and inter-institutional jockeying evident elsewhere have not been dominant drivers in this system. However, this is changing somewhat, with competitiveness now on the increase and a buyers’ market developing from a student point of view. This enrolment management focus has expanded the range of student service activity at some institutions to include recruitment (domestic and international), admissions, classroom services, student Web services, student information services, and in some cases, academic advising. Partnerships within institutional planning are also much closer. A key driver in this emphasis is the recognition of students as customers, as well as learners, clients, and citizens. Since 2000, Red River College, York University, University of British Columbia, and Université de Montréal, to cite a few examples, have all moved responsibility for enrolment services and registrar functions into the student affairs portfolio. As with student learning, this has been accompanied by a growing professionalization of staff in those roles.

A third major development impacting the nature and organization of student services on campus has been the renewed attention to vision and strategy at the institutional level. Student services units can no longer stop at professing student–centredness; post-secondary settings are now asking those units to help advance institutional aims more directly and to provide evidence that they are accomplishing that intent. This is resulting in many new program engagements and institutional initiatives, including internationalization of the campus, student mobility, “building” the entering class for certain attributes, undergraduate involvement in research, professional development for research graduate students, community service learning, industry and association mentoring programs, alumni relations, sustainability efforts, citizenship education, proposing and recognizing students for external awards, providing services to university town residents, helping implement and act on institutional surveys such as the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE), and partnering on fundraising goals. This explicit expectation to serve the institution and its mission, as well as students and faculty, is also changing the scope, organization, and delivery of student services. Recent strategic plans issued, for example, by Ryerson University (2008), Mount Allison (2007), Fanshawe College (2008), and University of Alberta (2008) all illustrate this contribution of student affairs to institutional advancement.

Finally, the emergence of a more diversified funding base has also shaped student services across the Canadian post-secondary sector. The TD Bank Financial Group 2004 reported that the percentage of direct funding from government decreased from 80 per cent to 63 per cent between 1989 and 2003 – a trend that is apparently continuing. This has also generally been accompanied by an increase in the tuition and fee share borne by students; third-party funding sponsorship, including research overhead; fundraising; and training contracts. Organizational responses to these phenomena have included new advisory councils (e.g., students, employers, industry sectors, the community), formal and mandatory student consultation processes, community engagement officers, employment outreach coordinators, guidelines for strategic alliances, regular accountability reports to various stakeholders, and hiring of fund development professionals within student affairs. The time and resources devoted to managing the issues and relationships that follow from broadening the funding base are significant. In a typical issue of the monthly NewsWire News compiled by the Canadian Association of College and University Student Services, one-third to one-half of the topics relate to these aspects of student affairs practice.

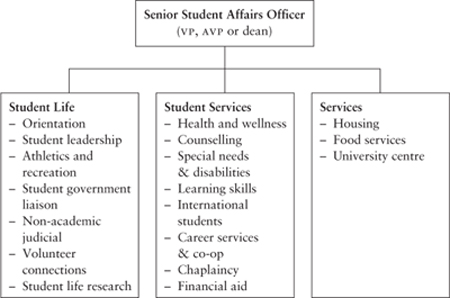

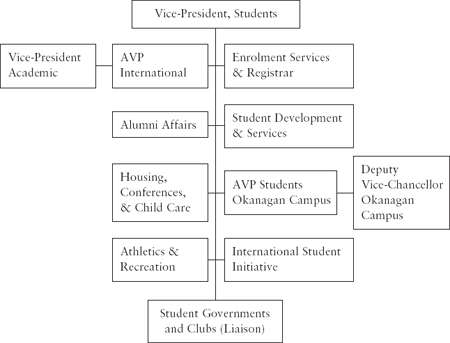

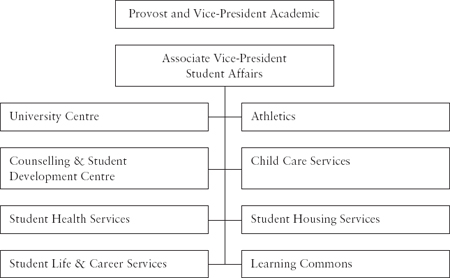

Figures 2.1, 2.2, and 2.3 depict contemporary student services organizational structures for a medical-doctoral university (University of British Columbia), a comprehensive university (University of Guelph), and a large urban community college (Mohawk College), respectively. The student services divisions at all three institutions are well regarded. Compared to their relatively uniform organizational arrangement of twenty years ago (See figure 1), there has been significant differentiation of functions and organizational forms. Five key considerations guide local choices for each institution. A brief discussion related to each follows.

University of British Columbia

Figure 2.1

Student Services Organizational Chart

Residential campuses devote greater per capita resources and attention to campus life, health, safety, counselling, non-academic judicial concerns, and orientation. Student services on commuter campuses pay particular attention to retention, the needs of mature and part-time students, student financial assistance, and furthering a sense of engagement.

A student services portfolio that includes enrolment management will look and feel different from one that does not. The organizational culture best suited to accomplishing enrolment management functions (i.e., customer-, data-, and procedure–driven) is different than the traditional student services organizational culture (i.e., client-, experience-, and practice-driven). Having these two broad functions together in a portfolio can generate important synergies for student success and reduce waste due to boundary battles, but does require sustained attention to the different organizational requirements of personnel in those functions and to the forging of common cause at the portfolio level.

University of Guelph

Figure 2.2

Student Services Organizational Chart

Student service divisions include units from those operating with no reliance on government or tuition funding (e.g., housing, childcare, and health services) to those often funded exclusively from such sources (e.g., student financial assistance, orientation, access and diversity, assessment/research, learning services, peer helping, and student leadership). Some units, such as athletics, counselling, and career services, are typically funded through multiple sources, each with its own expectation and accountability demands. Of particular note is the growth since 1995 in the proportion of student services funded through compulsory ancillary fees. This is most pronounced in Ontario, where at some institutions (e.g., University of Toronto), nearly all of the salary and non-salary operating costs of units such as counselling, careers, advocacy, student leadership, and campus life are funded directly by students. As the provinces continue to restrain tuition increases, even as the demand for such student services is increasing, the proportion of service funding from this fee source will probably increase.

Mohawk College

Figure 2.3

Student Services Organizational Chart

As referenced in the Canadian Association of College and University Student Services’ mission statement, the choice of whether the senior student services administrator reports directly to the president or to the senior academic officer is an important one, with both options having strengths and limitations. Colleges and some universities are focused almost exclusively on the undergraduate experience and have a more naturally holistic view of student learning and development. In these institutions, a direct report to the vice-president (academic) may be quite natural. An exception usually revolves around enrolment management issues. If a student services portfolio includes enrolment management responsibility, and that area is of particular concern to the institution, one will often see a direct report to the president.

Whatever the report, two considerations are key. First, the goal is to have a seat at the cabinet table. If the president also functions internally as senior operating officer (SOO), a direct report to the president is advantageous. If the vice-president (academic)/provost serves as the SOO, a direct report to that individual may be quite satisfactory and even advantageous, in terms of budgetary support and linkage with faculties and the institutional planning unit. Second, it is important to be a full member of the committee of deans and directors. Promoting student learning, strategic enrolment management, and other institutional aims requires effective and enduring partnering with deans and their faculties. Having credibility within that colleague group, along with carrying and communicating the student affairs mission, is the most important emerging leadership requirement for senior student affairs officers.

Until the late 1980s, it was customary and sufficient for student services staff in Canadian institutions to have grown into their roles from experiences of student leadership in various units (e.g., residence life, orientation, recruiting/advising, advocacy) or to have immigrated into them from beyond the educational system with established professional credentials (e.g., health, personal counselling, learning skills, career education). This was largely true for senior student affairs officers as well, who were often tenured faculty. Since institutions had no access to Canadian student affairs professional preparation programs at the graduate level, this form of training was natural and convenient. However, emerging influences such as those noted above have placed new challenges on those roles, and the lack of a pool of qualified candidates at many institutions with training in the broad field of student development and student services and enrolment management is limiting the capacity to deliver on those new expectations. A number of schools have shaped their organizational structures to develop their own broadly prepared staff – through sponsored institutes, internships, job rotations, and educational leave programs – and to take fullest advantage of those with formal training. While the dearth of student services staff, particularly managers formally trained in the field, is a concern, some advances are being made in developing Canadian educational programs and strong efforts are being taken to repatriate Canadians who do graduate student services training elsewhere.

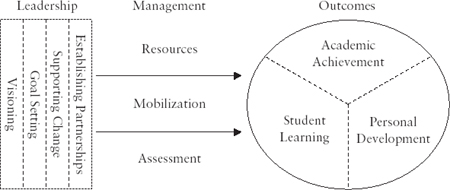

The institutional success of student services also depends on the senior executive’s understanding of the leadership-management distinction. As depicted in figure 3, the leadership and the management of student services require different strategies and processes. Whereas leadership entails the purpose and direction of services, management focuses primarily on their implementation and evaluation. Leadership of student services on campus involves visioning, goal setting, supporting change, and establishing partnerships; management assembles and allocates resources, mobilizes staff involvement, and assesses the effects of various initiatives and programs. The resultant outcomes are academic achievement, student learning, and student development, all of which are tied to institutional advancement as well as student success.

Figure 3

Leading and Managing Student Services

Leadership in student services begins with visioning. However, vision is untethered, absent of knowledge about one’s students and institution, lacking in concrete description of the current situation and the desired future state. Goal setting follows and brings the particulars to vision: What outcomes are essential? What resources are needed to implement it? With whom must we work, where, and how? This process specifies what will be done to enact the vision in real and observable ends. Action on the vision then requires a third process: supporting change, including how to make the case for student success. The final leadership consideration in this sequence is establishing partnerships. The organizational alignment needed to enhance student success in post-secondary institutions proceeds from partnerships, especially with parties beyond student services units.

Vision is an image of the future we wish to create. Practical and focused on results, vision turns the direction described by the mission and sense of purpose into a destination. It transforms a description of what is held in common into a story about what will be accomplished in common. This requires an unflinching understanding of the institution within which it is to be enacted and the students it is to serve.

Learning about the historical roots and origins of our institution and its journey is a critical prelude to the process of visioning. Read about the institution; almost all colleges and universities have published histories. Listen to what it might tell you; seek out alumni and available reports that inform its workings. Dig into back issues of the student newspaper and the photo archives; appreciate the long-term as well as the short-term view. Use the following questions to reflect on the attributes of your institution and what they might imply. How does its sponsorship, public or private, shape what it does? Is it primarily undergraduate in its focus or oriented more toward research and advanced graduate studies? How does its location (i.e., rural vs. urban) set a context for its mission? What do these features infer about stakeholders and accountability? Are the organizational expectations in use rational and bureaucratic (Barr and Associates 1993, 96)? Alternatively, are they collegial, political, or less conventional (e.g., organized anarchy or a learning organization) in practice (Komives, Woodard, and Associates 1996)? What are key features of the physical, human, organizational, and constructed dimensions of the institutional environments (Strange and Banning 2001)?

Understanding one’s institution also entails an understanding of its strategy. What guides goal setting and major decisions? Is there a declared strategic plan and is it followed? If not, what does the institution follow? How is progress assessed and do results influence what happens subsequently? Is the strategy broadly understood and how deep is the ownership of it?

Student learning and development happen at the intersection of the student story and the institutional story. There are many aspects to approaching the question, “Who are our students?” Building the capacity within student services to source this information in a variety of ways is critical. Surveys at several points in time are indispensable (e.g., National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE), Canadian University Survey Consortium (CUSC), National College Health Assessment (NCHA), Cooperative Institutional Research Program (CIRP) Freshman Survey, and cohort studies have particular power (e.g., BC Council on Admissions and Transfer and the BC Provincial Follow-up Survey of Graduates). One aspect of this information is demographic; the second is student self-report. Some of the latter comes through surveys, but much of the information on student characteristics, needs, service use, and perception that is helpful for organizing student services comes via focus groups.

A third type of knowledge about students comes from direct engagement. One of the single most powerful interventions a student services professional or educator can have with a student is to ask what he or she is learning, whether in a specific course or a co-curricular experience. Student peer helper staff members perform a very important role in this regard by sharing with staff current information about students. One can also learn who our students have become by spending time with alumni and listening to their observations, assessing the learning and development outcomes they have experienced, and polling their perceptions. Constant attention to ways of building knowledge about students must become a mindful habit if their expectations of success are to be understood.

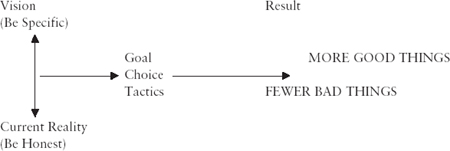

The creative tension established between a specific vision and an honest depiction of current reality leads to goals, choices, and tactics. A simple but powerful way to describe goals is: either “more good things” or “fewer bad things” (See figure 4). As crude as it may sound, these two outcomes describe how the success of a particular undertaking is often judged.

Students have a large stake in the attainment of institutional goals and they need a voice. Typically, they can find that voice but, like any developmental task, the process needs to be built for success. Students are often brought into higher education systems without adequate orientation, data, mentoring, or feedback. More recently, however, consultation expectations are being embedded in policy to assure that student leaders have access to appropriate and adequate information in the decision-making process prior to recommending one action or another (e.g., enactment of student fees in Ontario and tuition increases in British Columbia). Such a provision has helped clarify expectations and processes.

PRODUCTIVITY

Figure 4

Leadership and Goal Setting

Attention is generally paid to whether students are adequately “cared for,” but staff members are all too commonly taken for granted. Most post-secondary institutions under-invest in their staff, and scarce professional development resources are often the first to disappear in a time of retrenchment. In addition, college and university managers are typically very under-prepared in the skills of training and coaching, the management development approaches shown to be the most effective in securing employee engagement and commitment.

One approach of particular promise is student peer-helping programs: following a period of orientation and training, and under supervision, juniors or seniors support and serve fellow students. Properly designed and executed, the potential for leveraging service extension with student learning and development is enormous, and the areas of possible application (e.g., counselling, alumni, equity, service learning, and sustainability) go well beyond those traditionally considered, such as orientation, academic support, wellness, leadership, and careers.

As vision is articulated and translated into goals, and staff and students become engaged in the achievement of those ends, change is inevitable. Several dimensions then require explicit attention to achieve a critical level of momentum. If the vision is not communicated and understood, the result is often confusion. If staff members do not have adequate skills to implement the vision, anxiety can paralyze the process. If incentives and resources to support the change are not sufficient, the pace of change can slow or even come to a halt. Finally, if an action plan is not clearly articulated, it will lead to many false starts.

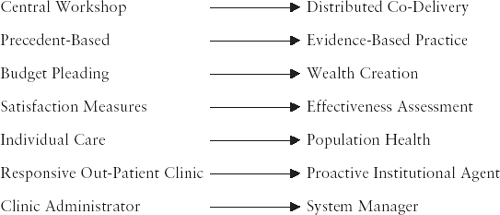

Successful change management often means thoroughgoing analysis of our own organizational situations – not a common enough occurrence in institutions committed to critical inquiry. At one unnamed institution, for example, counselling services was aware of a growing tension and some dysfunction as it entered the budget planning cycle. The usual incremental tweaking was not achieving what was needed. In the absence of an explicit formulation, however, none of the ways forward seemed obvious or attracted much support. After a relatively short group process with some facilitation on the interaction of institutional story, student story, and the principles guiding service delivery, the unit conceptualized a set of shifts it was experiencing (See figure 5). This was enough to loosen the temporary paralysis and for the staff to select likely action points, test through consultation, and then put a plan in motion.

Figure 5

Characterizing a Counselling Service Shift

Organizational politics shape resource assembly and allocation. They can be rational or not, self-serving or not. Student services professionals must embrace the power dimensions of reality and become effective institutional politicians. Students count on it and deserve it. Key attributes of those who successfully lead in this sphere include being competent, understanding organizational positioning and timing, accepting conflict, and maintaining integrity. As institutional change unfolds, various arrangements and distributions may be at risk, and it is natural for current stakeholders to resist change on behalf of the status quo. Recognizing that investment, and the power that maintains it, is an important step in bringing others along. In that regard, ideally, any proposed state becomes at least as attractive as things remaining the way they are.

Few things are more effective in support of desired change than a well-crafted policy, grounded in solid organizational analysis and aligned with the unit’s vision and key operating values. Conversely, few things pose a greater impediment to real change than a situationally convenient and idiosyncratically derived policy that rapidly becomes the source of a larger set of problems. Freedom of speech or harassment/discrimination policies spurred by particular incidents are notorious in this regard.

Despite concerns that post-secondary education is becoming more privatized, economically and psychologically, it is becoming more and more clear that we do not do anything on our own. The goals may be settled, the case made, and change requirements anticipated, yet it is still all about systems: learning is socially constructed and organizing only happens with and through others. Partnering is a basic operating principle in the institutional leadership process and explicit attention to building key relationships is foundational to effectiveness. From the perspective of student services, essential partnerships must include student groups, academic units, and community constituents.

STUDENTS AND STUDENT GROUPS

Showing up is everything in conveying to students a desire to understand and respond to their needs. As the saying goes, “You have to be there.” Processes with Canadian post-secondary student groups, particularly elected governments, tend to be informal and agendas are heavily influenced by individual personalities. “Being there” encompasses understanding, empathy, and presence. Be aware of the main features of your student government: Is it unaffiliated or a member of the Canadian Alliance of Student Associations (CASA) or the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS)? What is the policy platform of the particular national organization? Are candidates nominated in slates or do they campaign independently? Are fees based on a referendum or can the elected council approve them? Does the student government have its own building? What is the student government’s overall fiscal health and how dependent is it on retail enterprises and alcohol sales? How do constituent student groups at the faculty level relate to the central student government? What is the role of student association professional management staff and how have they constructed their relationship with the college or university administration?

Listening, respecting, suspending judgment, and honouring the highs and lows that student governments experience are behaviours to which student organizations are extremely attuned (See chapter 7). A student services practitioner or unit lacking in this regard will not have real legitimacy, whatever the formal mechanisms. “Being there” also means presence: physical presence on a drop-in basis and when asked; responding quickly to email and routinely forwarding information without being prompted; encouraging colleagues to participate in events and student planning processes; creating physical spaces where students can gather and interact informally with faculty, staff, and alumni; and being a voice for students within the institution on those occasions when students may not have an opportunity to raise their own.

The same broad approaches apply to unelected student groups and clubs and to the many less formal student assemblies. It is as much about attitude as it is about strategy. For example, many staff commute on public transport. Consider how they spend that time: some immerse themselves in newspapers and incident reports; others habitually connect with students, asking how things are going and what they are learning. There is a difference.

For student services managers, surveys can be significant in building relationships when jointly developed with student groups, often accelerating action planning. Focus groups offer similar benefits in that they tap a stream of student sentiment often not represented through formal elected or student group channels. Students, as individuals and in groups, are not only the recipients of our services but also critical partners in the achievement of institutional goals.

ACADEMIC UNITS

We work in academic institutions, and academic units and programs are the primary interface for most students. Furthermore, the individuals most directly able to influence student success are faculty and instructional staff. Student services cannot be effective in promoting student success without robust and mutually supportive relationships with faculties and degree programs. Key to this relationship is generally someone at the associate dean level with formal responsibility for students.

The overlap of an associate dean of students portfolio with topics of concern for student services professionals is significant. To cite a few, they include enrolment management; student characteristics, needs, and outcomes; need-based financial assistance and merit-based awards; academic progress; experiential educational opportunities such as co-op, international mobility, and service learning; career development and job placement; behavioural incidents; and connections with alumni. Student services primarily serves students, yet faculty and faculty units are also critical clients. This point requires deeper appreciation on the part of student services administrators if supportive faculty alliances are to be achieved. The creation of a faculty service centre, for example, within student information systems is a welcome move in this regard.

Universities and colleges are complex systems, and the ability to do what is important to support student success improves as our knowledge of the system as a whole advances. Unions, the office of legal counsel, plant operations, and environmental health and safety are all examples of units that bear directly on student success, but are often alien to student services managers, much less individual staff. Leadership in the student services portfolio must recognize this and take steps to build shared understanding and personal familiarity with these units.

COMMUNITY GROUPS

Goals such as “broadened community engagement,” “student citizenship development,” and “collaboration to advance the public good” are appearing with more frequency in institutional mission statements. In addition, academic programs and individual students are looking for experiential learning opportunities that go beyond the direct purview of the institution. This presents student services professionals with new opportunities and responsibilities. Through recruitment and admissions we are in touch with secondary schools and other educational partners. Through international education we come to know local consular offices, and career centres develop extensive networks with employers. We have formalized opportunities with a broad range of community groups and agencies to engage interested student volunteers, and we have established programs with community mentors, many of whom are alumni/ae. Our expertise in community networks needs to be forcefully brought to the attention of those looking to expand institutional community engagement. Advisory councils, such as those some institutions have convened with secondary school guidance counsellors, open up new connections across programs and fields; council members are a valuable and unique source of feedback on the institution and on the capabilities of students and graduates.

Returning to the model in figure 3, it is clear that achieving student success in post-secondary education requires not only solid leadership competencies but also a set of management skills essential to implementing a vision and goals. As depicted, these can be characterized as assembling and allocating resources, mobilizing staff involvement, and assessing the effects of various initiatives and programs.

Love and Estanek (2004) urged student services practitioners to move beyond the usual considerations of money, space, time, and personnel in thinking about resources and to think instead of awareness, effectiveness, and organization. In their view, awareness of resources is often too limited, a prime example being the way individuals tend to focus on faculty, staff, and students when considering “people.” Many of the most innovative ways of expanding resources involve volunteers, parents, alumni, and members and groups from the broader community. Relationships are also under-appreciated as a resource component. Much of the current work that needs to be done to support student success can only occur through new partnerships. The process is the same whether it be community placements for experiential learning, seeking potential donors, community building with the police, or working with plant operations around deferred maintenance for classrooms. The management challenge is which relationships to invest in and how to work across boundaries.

Expanded awareness of resources also extends to the staff group. Some student services units, after defining an issue, have put out the equivalent of a request for proposals within their own organization to tap resources and expertise of which management is not aware. This can be liberating, and often opens a very different window on what staff training and development programs can be about and can provide an impetus for mini-experiments in job–sharing, temporary reassignment, and skill banks.

Improving resource effectiveness can be particularly challenging in student services, as there tends to be a strong allegiance to doing what has previously been done. Suggestions for re-examination are often received as veiled attempts to shift resources away from supporting students toward less student-centred institutional objectives. Case studies and other stories from “outside” are often the best way of introducing constructive reframing. Web-based service provision, student peer-helping programs, and intentional activities with alumni in support of students are approaches to service delivery that expand available resources at very modest incremental costs, build skills of self-reliance and lifelong learning in students, increase the sense of institutional affiliation, and promote citizenship development.

A broadened view of resources leads to an abundance, rather than a scarcity, mindset and one begins to see and experience possibilities for augmented resources in many areas. Some of the “technologies” related to this are relatively new to Canadian student services work. For example, the culture around being an alumnus/a is different than in many universities and colleges in the United States. Consequently, in Canada, alumni/ae activities have tended to be under-resourced. With the possible exception of athletes, little emphasis has been put on cultivating student subgroups in alumni/ae terms (e.g., elected student leaders, residence life staff, student journalists). Alumni/ae are an under-utilized resource. One of the main opportunities for student services resource augmentation is to work closely with alumni affairs and development professionals, beginning with joint programs centred on current undergraduate and graduate students. Finding ways to help alumni/ae connect with each other and with the institution can generate enormous dividends.

Related resource augmentation technologies are fundraising, grant writing, and community compacts. Resources from private individuals, foundations, government agencies, or NGOs (non-governmental organizations) are more available than is often presumed. However, any such request must be grounded in clear divisional and institutional priorities. Grants must be looked at realistically, as they consume resources (e.g., time, people, space, facilities) potentially available for some other use. That said, third-party grants represent a very effective way of seeding new initiatives.

Mobilization is the management activity centred on building capacity across key domains and then creating conditions to maximize the ability to access, sort, and apply resident expertise to the problem or opportunity at hand. Knowledge is one key capacity in this activity. Post-secondary institutions function in complex and turbulent environments: uncertainty is high and the organizational whitewater flows constantly. Knowledge exchange opportunities need to be embedded, habitual, and reinforced. Some have made a beginning in this regard by concluding a meeting or organizational episode with each participant taking time to reflect on: “How was this experience and what did I learn?” We ask students what they have been learning; routinely asking the same of each other could have enormous dividends.

Approaches to building knowledge must move in concert with building involvement. Knowledge has no real currency until it is exchanged, and student services personnel need to be practiced in various forms of building student involvement. This begins by finding out how students wish to engage a topic (e.g., face-to-face, Web, open forum), where (e.g., classroom, social space, residence, student union), and when (e.g., during the work week, evenings, weekends).

Team management is another essential mobilization capacity. The word “team” implies a common vision, member inter-dependence, and a system of recognition and reward. Attention is needed to ensure that system aligns in the same direction as the desired team output. Higher education teams, be they a group to advise on academic readiness programs or the executive team of the student services portfolio, need to be intentional in their operating principles in order to achieve cohesiveness and efficiency. For example, at one unnamed division, the management team has adopted the following rules of engagement: (a) generous listening, (b) being on each other’s side, (c) straight speaking, and (d) managing each other’s reputation. Articulating and adhering to a shared value platform such as this is often liberating and up-building.

Ironically, given the typical reaction to policies and procedures, they have enormous power to mobilize resources by building common purpose and maximizing efficient use of energy. Some institutions have undertaken policy audits, often with the help of involved students, to identify policies and procedures that can be eliminated or overhauled. Review of alcohol and release of information policies, for example, lend themselves well to this.

Assessment is the third management process highlighted. It is about learning and improvement, at both the individual and organizational level. Effective units oversee the resources, mobilize and maximize system capacity, and then assess outcomes to determine impact, stimulate learning, and guide continuous improvement. Intentional and ongoing assessment of student learning and development and program outcomes should be part of each student services professional’s mindset and of the institutional culture. Assessment results are crucial to priority setting, resource allocation, and improved student success and service outcomes.

Upcraft and Schuh (1996), Bresciani, Zelna, and Anderson (2004), and Whitt (1999) offer excellent reviews of comprehensive frameworks for assessment. Typically, the questions of interest are positioned as an assessment cycle:

1 What are we trying to do and why?

2 What is my program supposed to accomplish?

3 How well are we doing it?

4 How do we know?

5 How do we use the information to improve or celebrate successes?

6 Do the improvements we make work?

Distinguishing between different kinds of outcomes – program outcomes, student learning and development outcomes, input outcomes, student needs outcomes, and service utilization outcomes – is important. Assessment also occurs at different levels within the organization: individual student or staff, program, unit, portfolio, and institutional. A range of assessment tools and skills are required.

The first set of basic questions guiding assessment relates to intent: What is the objective of interest? What is the purpose for assessing it? Who or what is the object of the assessment? The next set of questions relates to assessment tools: What is the best assessment method? How should the data be collected and who should collect them? What instruments should be used? How should the data be recorded? Key criteria in choosing tools and methods should include input from the assessment client, the capabilities of those to be involved, resources available to conduct the assessment, the prescribed timeframe, how results will be reported, and who will have access to them.

Paying careful attention to ethical considerations related to an assessment project is also critical. Failure to do so can give rise to questions of legitimacy, where there is already ambivalence about whether student services professionals qualify as “investigators,” and where the ethics review boards may have limited understanding of assessment approaches akin to research but administrative in their focus.

Generating a quality assessment plan is only half of the challenge; the other half entails teaming up with the assessment client to elicit an endorsement of the results when they are delivered. A partner-like relationship is key to ensuring that the assessment effort is related to objectives that are meaningful and important to all involved. In addition, the focus should be on using assessment as an aid to living into a desired future, rather than as a blade to dissect what has already happened. Such positive and intentional engagement from the outset can increase the probability of relevance and the adoption of results once the assessment is completed. Well-designed focus groups with students, early in the project, can help clarify areas to be addressed in the assessment and heighten student government and student groups’ awareness. Unit or organizational level assessment will typically involve student services personnel coming together with academic administrators, faculty, and other constituents, both on and off campus; the secondary gains for student success arising from such collaborations are often significant. The goal of a partnership approach is to support a positive impact.

Collaboration should continue throughout the assessment project. Assessment data should either inform continuous improvement decisions or specifically test a proposition. Being clear on the purpose, rather than the object, of the assessment is very important. Specifying whether that purpose is program performance, unit mission, better decision-making, resource reallocation, or policy formulation will improve the assessement’s intended impact. A University of Toronto report, Measuring Up (2005), which utilizes National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) data to assess progress toward identified student experience objectives, illustrates one such approach incorporating these basic assessment elements.

This chapter began with an overview of changes in the external environment that prompt organizational reconsideration of student services at Canadian post-secondary institutions. Some of those influences continue and new ones arise in the form of those highlighted below.

Feedback from individual students, alumni, employers, and surveys such as the NSSE suggest that there is considerable room for improvement, especially in the instructional experience that students report. The emerging buyers’ market for places in institutions and the pressure for a good return on the increasingly expensive public and private investment in post-secondary education suggest that a higher priority is being placed on ensuring that students succeed if at all possible. Student services divisions are being challenged to have current assessment data, to move beyond individual programming to group and systemic interventions, and to find new ways of collaborating with faculty colleagues to improve the learning experience for students. Innovations such as cost-sharing student development officers with faculties and locating them in academic units are increasingly seen as a way to share skill sets and data, and build ongoing partnerships. Whitt (2006) offers a constructive and comprehensive set of “lessons” for thinking about the student services contribution to academic success, and James (1999) reviews operational considerations for learner support and success, particularly in the context of Canadian community colleges.

It is a time of uncertainty in the government student loan landscape. The proportion of assistance in the form of grants is being reduced; tuition and costs have risen significantly in many jurisdictions; and for increasing numbers of students, the necessity of part-time employment is impinging on their ability to have a full educational experience. For many second-degree programs, such as law, dentistry, and medicine, reluctance to take on more debt is skewing the class profile and exerting a powerful steering effect on the choices many students in the program make as to what and where to practice. Student services divisions play a key role in developing homegrown financial support mechanisms, providing education toward financial literacy, and advocating strongly with students at the provincial/ territorial and federal government levels for a more coherent and responsive financial assistance program.

Much needs to be learned and done to make our post-secondary institutions inviting and supportive for Aboriginal students. This will involve working directly with local secondary school systems and First Nations or urban Aboriginal communities; using fresh processes for planning and consultation; exercising flexibility in the application of established standards, while still ensuring quality; having more Aboriginal staff at our institutions; and providing training for all staff with respect to the opportunities and challenges faced by Aboriginal students.

As well as building support in the broader community and achieving their business plan goals, institutions are striving to be distinctive and to show how they add value. The amount and type of student engagement, the quality of the co-curricular experience, and what alumni have to say about the institution are all becoming more pressing student services division concerns. Those with enrolment management responsibilities have the additional job of packaging the university’s story in an appealing manner while being genuine about the experience of their current students.

The Canadian post-secondary system is being called on to prepare our students to be global citizens and agents for positive change. With established programs in leadership, sustainability, student mobility, and community engagement, student services divisions have an unparalleled opportunity to help their institutions meet these educational goals. Importantly, this includes the challenge of identifying outcomes that are relevant and measurable.

Alumni/ae services are very underdeveloped at Canadian universities and colleges. It is now becoming apparent that many institutional aims can be accomplished more powerfully and expeditiously if connected alumni/ae are mobilized in their pursuit. In the long term, positive alumni/ae relations are a product of students having a good educational experience while at the institution. Student services programs can contribute expertise about how to help current students begin thinking as “alumni/ae in residence” and seeing graduation as a process of joining something for life rather than departing the institution.

As the competition for the best and brightest students heats up among institutions with graduate programs, the quality of the experience for those students is paramount. Graduate students in research and professional programs are increasingly impatient with our traditional support mechanisms and anxious to receive broad-based professional development, career guidance, and assistance toward timely completion, and to have a respectable quality of life while in their programs. In this regard, one challenge particular to Canadian student services is to ensure that a number of staff have had a graduate student experience so that there is a deeper understanding of the educational context for those students.

Beyond the usual concerns of meeting enrolment targets and budget parameters are particular issues of sustainability in student services systems. Prime among these are the research and development and ongoing maintenance required to sustain a student information system, resources to support the voracious demand for new and updated Web-based applications, and the growing expectation that increased staffing costs for services such as careers, personal counselling, and health will be met through revenue streams generated by those services rather than through core institutional funding. An even harder push may come as to whether an institution needs to “make” a particular service or can outsource or buy it from elsewhere.

Given the current foci on learning, strategic enrolment management, and advancement of institutional aims referenced earlier in this chapter, the skill sets being demanded of student services staff are changing and intensifying. In addition, the way in which traditional-age students now access and organize their personal and learning experiences, particularly in the context of electronically facilitated modes of relating, has opened significant gaps between the experience base of many student services managers and that of the students they serve. Students are less and less interested in “getting with our program”; more junior staff, adept in these newer ways of operating, are serving an indispensable translation function and need to be legitimized in that role. Also, more intentionality is needed to ensure that our students see themselves in the racial, ethnic, religious, and international attributes of our staff.

Third-party funding other than traditional government and tuition sources is increasing in strategic value, and many institutions now depend on such sources to fund core activities. There are important ethical, policy, political, and practical considerations around this evolving dynamic. Student services is often called upon to be a conscience in this dance between the objectives of marshalling additional resources and of safeguarding free inquiry. Institutions will be depending heavily on the student services division to have sufficiently robust relationships with student government, alumni/ae, and local community constituencies that it can undertake consultative processes in these areas of creative tension and help build both responsibility and appropriate relationships.

Remaining current on the leadership challenges of the senior student affairs officer is essential, and the list of resources foundational to the task is extensive. Although not complete, what follows is an informative, helpful, and inspirational selection. They cover a range of materials that examine both the specific and general contextual considerations that impinge upon this role, with some addressing the functions and purposes of student services, others current trends that affect their implementation, and last, those that give insight to various leadership needs and approaches.

In addition to this book and among the foundational resources is Student Services: A Handbook for the Profession (Komives, Woodard, and Associates 2003). This volume offers a straightforward treatment of the core professional principles, theories, and competencies central to organizing and managing student affairs programs and services. Although grounded in the US post-secondary experience, many units are highly transferable to the Canadian context. In Where You Work Matters: Student Affairs Administration at Different Types of Institutions, Hirt (2006) utilizes a creative and practical taxonomy of institutional types to illustrate the varying roles and challenges of student services work in different kinds of post-secondary institutions. Manning, Kinzie, and Schuh (2006), in One Size Does Not Fit All, use a different taxonomy, centring on locus of activity, that draws out important organizational design considerations. While all the institutions in these two reviews are in the USA, the Canadian post-secondary system can draw lessons as it moves in the direction of greater differentiation and seeks to illuminate the new situations being faced by Canadian practitioners. Gilbert, Chapman, Dietsche, Grayson, and Gardner (1997) also add to the mix in offering a useful history of Canadian student services from the first-year experience point of view (See chapter 5). The profiles provided of programs and organizational structures at a large variety of institutions are very helpful in familiarizing oneself with the Canadian context.

Key purposes of student services are addressed in several comprehensive resources. First, Hamrick, Evans, and Schuh (2002), in Foundations of Student Affairs Practice: How Philosophy, Theory, and Research Strengthen Educational Outcomes, use abundant examples to emphasize institutional-level considerations in student affairs. Their point of departure is student learning, as they highlight key student outcomes such as democratic citizenship and life skills. Several other authors (e.g., Harvey-Smith 2005; Whitt 1999) embrace this end goal for student services by exploring, for example, the mental models that guide our work, what it might mean for the student affairs enterprise to be more learning-centred, how we can form partnerships with our academic colleagues, and what we need to know and be able to do to foster student learning or what it means for an institution to adopt a thoroughgoing focus on being a learning organization for the transformative support of the learning paradigm. In Learning Reconsidered: A Campus-wide Focus on the Student Experience (Keeling 2004), a joint effort of the National Association of Student Personnel Administrators (NASPA) and the American College Personnel Association (ACPA), a discussion of the context, process, and content guides integrated use of higher education resources in the service of learning that is transformative and responsive to the whole student. It offers a shared vocabulary and guide for student affairs–academic affairs partnerships striving to focus on student learning outcomes. Assessing Student Learning and Development: A Handbook for Practitioners (Bresciani, Zelna, and Anderson 2004) provides techniques to determine success by outlining processes and methods for assessing student satisfaction, personal development, and learning outcomes, and by including a discussion of best practices, benchmarking, and peer review.

Leadership of the student services institutional portfolio is the focus of several resources that speak, directly or indirectly, from the management literature as well as from personal testimony to the support of strategic decision-making in the context of student affairs. For example, Love, and Estanek (2004) utilize recent insights from organizational theory to help student affairs practitioners understand and work with organizational structures and processes. They argue convincingly for a fresh way of thinking about organizational power, leadership, resources, assessment, and technology. Brand (1999), author of Whole Earth Catalogue, offers a surprising treatise on time and responsibility in the form of a series of meditations for managers. In the author’s view, the ever-shorter attention span and opportunistic stance we cause and accommodate – kairos time – is creating a colossal societal shortsightedness. He suggests that we owe it to our students, our institutions, and ourselves to recover what it means to take the longer-term, wise view – chronos time – and accept our big-picture responsibilities. Looking honestly and respectfully at the inherent conservatism of institutions of higher learning and teasing out what is unresponsive and deadening from what is faithful stewardship and wisdom is a truly worthy calling and a contribution that student affairs is uniquely qualified to help make. Fullan (2001) stresses the importance of the personal attributes of the leader, including enthusiasm, energy, and hope in leading change and strategic management at the organizational level. Authored by an experienced educational administrator and researcher, the theoretical constructs in this volume are accessible and replete with educational institution illustrations, and offer a helpful vocabulary for shared meaning. Similarly, Ellis (2003) addresses many of these points in her chapter for Dreams, Nightmares, and Pursuing the Passion: Personal Perspectives on College and University Leadership. This is an engaging and instructive personal reflection on the first two years of the author’s student affairs vice-presidency at the University of Nevada-Reno. Journal entries are clustered under headings such as “Connecting with the Faculty,” “Seeing Through Students’ Eyes,” “Navigating the State System,” and “Being Myself.” Some very helpful illustrations for the management topics of relationships and resources are introduced, bringing the concept of personal agency to life.

An appreciation for the current context of these challenges is found in the recent work of several Canadian authors. For example, Andres and Finlay (2004) feature an edited collection documenting changes in the social field of Canadian post-secondary education, and institutional responses in the face of such change. The contributions are largely based on college and university survey findings from recently completed graduate theses, and many of the authors are currently working in student affairs. This volume gives fuller meaning to the context and impact of the change drivers cited above in this chapter.

A 2004 TD Economics Special Report, Time to Wise Up on Post-Secondary Education in Canada, is a clear-headed analysis of post-secondary public funding and tuition levels in constant dollars. The report expresses concern at the increasing reliance on private (student) funding, suggesting the urgent need for student financial assistance reform. Eastman (2003) focuses on the strategic responses available to Canadian universities as they increasingly engage in marketplace activities and concerns to outperform competitors. Thorough consideration is given to topics such as budgeting options, the role of the (administrative) centre in a decentralized institution, and constraints on strategic management at the faculty level.

The effectiveness of senior leadership in post-secondary student services depends a great deal on being attuned to trends and events that shape the day-to-day operations of an institution; connection to current issues and best practices in the field is mandatory for anyone seeking to provide strategic leadership to a division as diverse in purposes as student services. An excellent resource is Communiqué, the national journal of the Canadian Association of College and University Student Services (CACUSS). Often thematic in content (e.g., mental health on campus), each issue serves as a handy barometer of current concerns and initiatives in Canadian post-secondary student affairs. Furthermore, it offers an opportunity for perspective sharing on important topics and provides a venue for relevant program descriptions and successful outcomes.

In conclusion, student services in Canadian higher education has evolved into a complexity of challenges demanding a well-informed approach that capitalizes on the emerging body of professional literature that informs what it does. Promoting the continued success of students entails an advanced appreciation of this knowledge base and the ability to implement these ideas into solid programs and practices. Effective strategy in all this demands a vision grounded in the best ideas, credible research, and most-proven experiences. Student affairs can expect nothing less from its campus senior-level leaders.

Success is a metric applicable to whole institutions and their divisions as well as individual students. While each of the various offices typically affiliated with student services contributes an important piece to the overall success of the division, and by extension that of the institution, it is the synergy of their collective action that most readily assures the college or university’s performance when it comes to supporting student success.