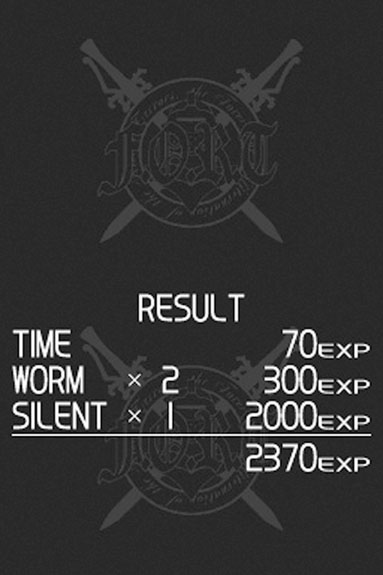

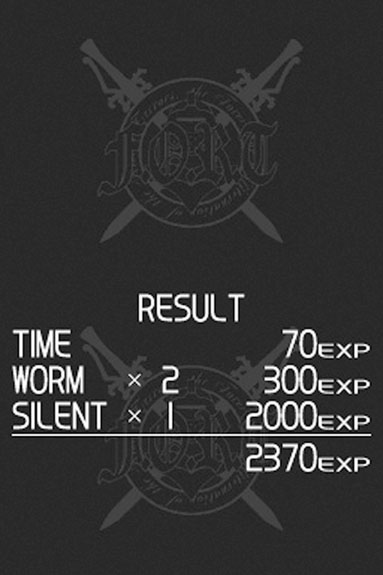

Figure 4.1 Lux-Pain’s experience screen (Killaware 2009).

When Language Goes Bad: Localization’s Effect on the Gameplay of Japanese RPGs

It is interesting that an analysis of language itself, arguably a core component in the construction of a game’s story and the development of character in role-playing games, has appeared as nothing more than vague ripples in the literature. This is not to suggest that language has not figured into analyses of games; rather, I contend that language as an analytical tool itself has been glossed over. At the risk of overgeneralizing, analyses of the subject tend to either emphasize game content, drawing connections between linguistically constructed story elements and larger non-game social discourses (Bogost 2007), or privilege the medium, maintaining a separation between the two realms based on differences in how they operate (Aarseth 2004).

Both approaches treat language as a representational vehicle; the irony is that language, as a rule-based system, fits the very basic definition of a game (McLuhan 1994; Lyotard 2002), and the implications of embedding the linguistic game within another rule-governed system – like RPGs, regardless of platform – have not been directly addressed in this context. My understanding of an ‘analysis of language’, then, differs in that I refer to explorations of the medium’s rule-based characteristics – its grammar (Chomsky 1957; Chomsky 1965) or pragmatics (Austin 1975; Lyotard and Thebaud 1999) – and how these rules construct gameworlds and intersect with more mundane corporeal existence. From this vantage, I am not interested in the compelling explorations of how to approximate the complexities of linguistic rules into a game so that the computer will understand nuance, but, rather, how existing and intuitive human applications of linguistic rules inform the game environment.

The process of videogame localization witnesses these concerns, and so I scrutinize the grammatical, semantic, and prescriptive operations of language within the American iteration of the Nintendo DS (DS) game Lux-Pain (Killaware 2009) to argue that language contains a ludic impulse and can be approached in terms of its impact on gameplay. Sociolinguistic theory informs this argument, as do insights into language from Austin (1975) and Lyotard (2002; 1999); discussion of the medium itself draws from McLuhan (1994) and Baudrillard (1994), peppered with scholarship from ludology. (For another sociolinguistic approach to language in videogames see Friedline and Collister’s chapter in this volume.)

While Lux-Pain was neither popular nor profitable, its inability to create even a ripple in the popular gaming market does not imply a dearth of critical potential. My rationale for choosing this game stems directly from the attention to language and its configuration in the videogame medium that guides this essay’s argument. The game’s spectacular failure as a localization more clearly elicits how language operates as gameplay – a good translation, to paraphrase Venuti (2008), smoothes over linguistic ruptures – the explicit operation of which would be difficult to parse from a better-constructed text.

Frasca (2003) broadly defines the ludic approach by stating that games ‘model a (source) system through a different system which maintains (for somebody) some of the behaviors of the original system’ (223). Pointing specifically to audiovisual components as the most frequently reserved features of the original system, he notes that games encapsulate more than what players see or hear, a point Aarseth (2004) identifies as integral to the study of games in general: ‘When you put a story on top of a simulation, the simulation (or the player) will always have the last word’ (52). While games may engage in storytelling, that is not necessarily their primary purpose, or, in cases like chess, even a condition of their existence.

Rather, games operate by a system of rules that may or may not parallel the semiotics of narrative. This fact is what Frasca (2003) alludes to when he states that ‘video games are just a particular way of structuring simulation, just like narrative is a form of structuring representation’ (224). The rules of games tell us how to play; the rules of narrative tell us how to read. DRPGs consist of both systems of rules, and to come to an effective analysis of the genre we must engage how these systems interact to construct the gaming experience. In this respect, language offers an excellent analytical entrance to these concerns as it, too, possesses the same protean nature; alternatively approached as a representational tool (see the general work of Lévi-Strauss) or generative system (Austin 1975; Searle 1989, Searle 1995; Lyotard and Thébaud 1999), it offers multiple modes of structuring the DRPG experience.

Fan reactions to Lux-Pain provide a doorway through which I argue language’s ludic potential. Three arguments form the core of this central claim: first, that violations in linguistic rules such as grammar and pragmatics potentially disrupt immersion in the DRPG game experience and thereby impact gameplay, a feature I refer to as immersive dissonance; second, that language can exceed the structuring of simulation organized by the game, resulting in an immersive dissonance motivated by semantic confusion; third, that this ability of language to operate both internally and externally to the game offers an analytical approach sympathetic to ideological critique. Before trekking these admittedly intricate paths, I begin with an overview of the Lux-Pain, including its genre classification and its plot.

Lux-Pain was developed by the Japanese game company Killaware for the DS, and Ignition Entertainment handled the 2009 distribution of the US localization. The game resists black-and-white genre classifications, mashing action, RPG, and adventure elements together to produce multiple gameplay interfaces. In terms of its DRPG characteristics, the game incorporates three distinct elements that scholars (Barton 2008; Wolf 2002) cite as definitive of the genre and shown in Figures 4.1 and 4.2: a formal leveling system, statistical representation of the protagonist Atsuki, and randomness.

Figure 4.1 Lux-Pain’s experience screen (Killaware 2009).

Figure 4.2 Quantification of Atsuki and his powers (Killaware 2009).

These elements are drastically simplified when compared to DRPG ‘classics’ such as SSI’s Gold Box, Origin’s Ultima, or SirTech’s Wizardry series, but their inclusion directly affects gameplay in that if Atsuki is under-leveled, no amount of touch-pen dexterity in the action-inspired sequences will help him overcome the various obstacles he encounters. In these sequences, for example, he inflicts damage upon whoever he is probing; the greater his skill, the less damage he inflicts and the more time he has to complete his task. As one progresses in the game, these elements become increasingly more unfavorable to the player – time becomes shorter and damage greater – so that leveling becomes necessary to counterbalance the increase in game difficulty. To complicate matters, each encounter plays out differently; the positions of objects he must find and their movements randomly change each time Atsuki confronts the same obstacle, leaving a small portion of the encounter to frustrating chance (Figures 4.3 and 4.4).

Figure 4.3 Battle sequence with Silent (Killaware 2009).

Figure 4.4 Time, damage, and randomness in typical encounter (Killaware 2009).

This emphasis on leveling and luck rather than skill aligns the game more closely with DRPGs than the other genres (Barton 2008), but the three general definitional guidelines noted above reflect Western historical indebtedness to the pencil-and-paper predecessors of the genre (Apperley 2006). Japanese role-playing games (JRPGs), emerging from different historical and social conditions, possess an aesthetic and gameplay different from their Western counterparts; this area, as Barton (2008) woefully notes, is academically undertheorized. Gamers, however, maintain – some with religious zeal – that story and character development are hallmarks of JRPGs (Nagidar 2008, and more generally the whole thread). In the land of the JRPG, immersion in the gameworld rules, and many fans see this as the true roots of RPG. Indeed, Lux-Pain spends more time advancing the convoluted themes of murder, suicide, and isolation than forcing characters to grind for levels or money. Lux-Pain’s official webpage describes the plot and premise of the game as such:

Lux-Pain is set in historical Kisaragi City, a town plagued by mysteries from small mishaps to murders – with no logical explanation as to why these events occur. It seems ‘Silent’, a worm born through hate and sadness, has infected humans and forced them to commit atrocious crimes. The hero’s parents, Atsuki, are victims of such crimes. To avenge his parents, Atsuki goes through a dangerous operation to acquire Lux-Pain in his left arm, a power so strong that his left eye turns golden when using it to seek and destroy Silent for good. (Lux-Pain Official Webpage 2009)

Silent infects people with negative emotions which appear to Atsuki as worm-like balls of moving light that meander around an infectee. In order to see these balls of light, referred to as ‘shinen’ ( , thought), Atsuki activates a power called ‘Sigma’ that enables him to literally scratch the surface of reality to see what lies underneath. In order to more efficaciously mete out his revenge on Silent for his family’s murder, Atsuki has joined an organization known as FORT which is comprised of individuals like him with the ability to see shinen.

, thought), Atsuki activates a power called ‘Sigma’ that enables him to literally scratch the surface of reality to see what lies underneath. In order to more efficaciously mete out his revenge on Silent for his family’s murder, Atsuki has joined an organization known as FORT which is comprised of individuals like him with the ability to see shinen.

The game takes place in Kisaragi City (the location of which is a problem addressed later). It contains everything one would expect in a town – a church, apartment buildings, bars – but what takes center stage in the game is the local high school. Early in the game FORT narrows Silent’s base of operations to the vague ‘someone operating through someone operating at the school’; as a result, what begins as a detective story resembling a cross between Dashiell Hammett and H. P. Lovecraft tropes transforms into something profoundly darker – the navigation of high school social banality. In his quest to track down the link to Silent, Atsuki enrolls in Kisaragi High as a transfer student and is thrust into the world of high school romantic and social drama; how he navigates these currents determines which of the eight endings the player experiences.

Figure 4.5 Sigma’s ability to reveal hidden shinen (Killaware 2009).

The emphasis on narrative and character development dovetail well with what fans perceive as the general conventions of JRPGs, but what makes Lux-Pain unique in this regard is the almost universal agreement, on account of its rife linguistic errors, that the US localization was released prematurely. One concise reviewer described the game by stating: ‘Dodgy localization is everywhere with typos galore’ (Castle 2009). A more gregarious reviewer expounded on these points by stating, in part:

So what is the game’s fatal weak point? Well, have you ever watched an anime DVD with both the dub audio and the subtitles on at the same time? Notice how the subtitles are basically saying the same thing as the dub actors are saying, but using different words here and there? That’s the entire localization of Lux-Pain … the only thing that’s wrong with it is … well … THE TEXT! It’s crappy. It’s horrible. It’s a complete and utter embarrassment! (Video Game Review: Lux-Pain for Nintendo DS 2009)

The emphasis both reviewers place on the game’s poor localization offers a starting point to theorizing language as a dimension of ludic gameplay. Games structure simulations which, according to Baudrillard (1994), are ‘beyond true and false’ in that they do not attempt to make referential prescriptive claims about the world external to their operations (21). They are, as discussed later, self-contained. Narrative, to overgeneralize, strives to forge such connections due to its understanding of language as a representational device. But telling stories is merely one function of language, and overlooking the game’s narrative does not throw the rules through which language operates out with the narrative bathwater. The fact that reviewer discontent with the game emphasizes how the localization impacts immersion in the gameworld rather than the narrative itself suggests a problem in rules, not story. For another discussion on this subject, see Henton’s piece in this same volume.

My argument regarding the ludic implications of language takes shape over the course of three major sections that build upon the insights of the last. I begin this analysis by focusing on a close reading of linguistic rules emerging from the audio and written channels of Lux-Pain; the argument remains, more or less, constrained to material generated internally by the game. The section after, however, examines how internal inconsistencies in semantics disrupt the game and claims that language as it functions ludically exceeds the structuring of simulation imposed by the game text. From here, I close with some critical implications these insights have for the study of games.

No matter how one approaches localization (see Kuzimski 2007; Chandler 2005), the underlying impulse of the practice relies on manipulating the rule-based foundations of the symbolic system whose combination forms the building blocks of story and character development prized in JRPGs. Some of these rules speak to readability and form a fundamental aspect of gameplay – I’m thinking of grammar here and gaffes such as Zero Wing’s (Toaplan 1992) ‘all your base are belong to us’. While Lux-Pain contains errors of this type, and they do contribute to the immersive dissonance of the game, errors in this vein do not contribute much to language-as-gameplay, given their rarity in the industry.

Figure 4.6 Localization errors in Lux-Pain (Killaware 2009).

Figure 4.7 Localization errors in Lux-Pain (Killaware 2009).

A more useful approach flirts with the semantic component of language as it constructs the gameworld, as meaning is generally seen as emerging from specific situations and speech communities (Hymes 1989; Labov 1991). Fortunately, Lux-Pain provides both obvious and subtle fissures from which we can see how gameplay is impacted by language, and I intend to tease out the implications of this through repeatedly returning to the question of where the game takes place.

Obvious examples of language impacting gameplay stem from the differences between the written and audio channels of the game. These differences first appear at the end of the prologue which orients the player to the game mechanics and basic points of the plot. Atsuki contacts FORT’s recon and intelligence officer, Natsuki, to ascertain the location of some odd shinen and she mentions that her job would be easier if she was in Kisaragi City. The exact location of Kisaragi City, however, depends on whether one listens to the audio or reads the text:

Natsuki dubbed: ‘I wanted to go to America, too … using viewing is easier at the actual scene.’

Accompanying text: ‘I actually also wanted to check out Japan but … the actual place is easier for viewing.’ (Killaware 2009)

This mismatch is not a minor concern, both in terms of the game itself as a marketed product and – more germane here – in terms of its navigation of tensions between the linguistic and ludic games. This disjunction between the written and aural channels continues through the entirety of the game, and the accumulated errors stress the ideological veneer placed upon localization as an accurate representation of the original text by revealing how language operates behind the proverbial curtain to craft part of the gaming experience. Through these errors, we witness how language interacts with, engages, and alters the world. Natsuki’s complete monologue, reproduced below, provides insight into these processes:

Natsuki’s audio:

1a) I wanted to go to America, too…

2a) using viewing is easier at the actual scene.

3a) But the chief says ‘no’.

4a) How mean, really!

5a) ‘I know why, you just want to see Atsuki, right?’

6a) That’s what he said; what do you think?

7a) Oh, I wanna go to LA and I wanna see New York.

8a) Also, I really want to try the food there.

9a) I’ve never tried it before.

10a) I said so, but he ignored me.

Accompanying text to audio:

1b) I actually also wanted to check out Japan but …

2b) the actual place is easier for viewing.

3b) Yeah, but the chief said no.

4b) You’re quite the bully …

5b) I get your alterior [sic] motive. You just wanna meet Atsuki.

6b) The chief actually said that. What do you think, Atsuki?

7b) You’re wrong. I wanna go to both Akiba and Genjuku.

8b) Well, I also really like Sushi and Tempura.

9b) … But I haven’t exactly partaken in either yet.

10b) Well, forget I said that … (Killaware 2009)

Natsuki’s monologue is of special interest in that it manages to distill in ten lines most of the faults reviewers and fans point to when they explain ‘how an entire experience can be ruined by poor localization’ (Shau 2009). Scanning the few lines in Natsuki’s monologue reveals quite a bit of evidence to support the claims of Shau and others regarding the localization being ‘poor’; the rather large leap in setting between (1a) and (1b), inconsistencies in spelling as seen in (5b), confusion over addressee as in (6a) and (4b), and general illogical statements such as in the pair of (8b) and (9b) demonstrate that the released product still requires some polish. What we read creates a different world and set of expectations that conflicts with what we hear, and while minor errors such as misapplied pronouns and other grammatical issues certainly contribute to this failure, more troublesome are those moments in which referential knowledge of the gameworld breaks down. Natsuki’s desire to eat sushi and tempura can make sense regardless of whether or not the game takes place in Japan or America, but the problem emerges from the fact that both of these locations are simultaneously presented as valid constructions of the gameworld.

The divergence in gameworld constructed by the two channels additionally impacts her character. Grammatical and semantic consistency in Natsuki’s voiceover suggest nothing dramatically marked about her speech, and this finds support with the inflection and other auditory cues provided; the written gloss, however, contains a number of issues that may strike the native speaker as odd. Line (4b), for example, points to an ambiguity in addressee. Given the nature of the speech, the second person pronoun should be understood to refer to the chief and her outburst more of an excited statement than direct address, but the ambiguity arises from the fact that Atsuki is present and there are no other cues to facilitate the intended reading. The rather interesting semantic logic between lines (8b) and (9b), where Natsuki complains that not going prevents her from eating the sushi and tempura she likes so much and immediately reveals that she’s actually never tried them, further contributes to her puzzling characterization offered in the two channels and potentially interrupts the game experience.

This interruption of game experience, I propose, orients language in a fashion akin to more familiar aspects of ludic gameplay, in that it directly impacts a player’s ability to become immersed in the gameworld, a condition that many players see as constitutive of the JRPG genre. The localization problems with Lux-Pain do not severely impact one’s understanding of the plot – the overall story is readable and relatively coherent – but the grammatical and semantic potholes consistently serve as reminders that the game is a construct and a translation. McLuhan’s (1994) speculation that media are co-constituted by other media explains the divergence between the audio and written gloss as symptoms of the operations of language embedded within different media, but this implies that the medium – in this case videogames of the JRPG console variety – regulates or somehow constrains language.

To some degree this is true, as technical limitations imposed by the DS cartridge prevent, for example, Lux-Pain from accompanying all written text with audio. But these limitations do not necessarily impact the rules by which language operates, and my claim that language can be approached as gameplay arises from its properties as a rule-based system. Unlike more traditional or conventional aspects of gameplay, however, linguistic gameplay derives from mechanisms both internal and external to the game. A brief overview of how simulations function will help ground this tension before an extended discussion of the prescriptive functions of language and the properties of naming.

In arguing that games structure simulation, ludologists implicitly tip their hats to Baudrillard (1994), who, building off of McLuhan’s theorization of media, notes: ‘it [the object] has no relation to any reality whatsoever: it is its own pure simulacrum’ (6). Games, in other words, are discursively self-contained and though they may draw upon resources external to them for content, these resources operate according to internal rules structured by the game – referential meaning included. This is a basic premise of so-called ‘suspension of disbelief’ and from this perspective we are able to overlook errors in location, logic, and the like, writing them off as idiosyncrasies tied to the gameworld itself. Natsuki’s desire to go to ‘Genjuku’ in (8b) and shown in Figure 4.7 can plausibly be seen as an actual place in Japan (or America!) rather than a misspelling of ‘Shinjuku.’ The term shinen, and untranslated words in general, reflect how the game structures pragmatics in a limited sense. From the perspective of simulation, the most that can be said about the lack of translation of shinen in the US version is that it must have some semantic or other social function or meaning within the gameworld. It is a referent whose meaning is supplied from within the specific situational context of the game.

The tension I allude to at the end of the previous section, however, lies precisely with the properties of language as a rule-based system that includes how words are pragmatically conceived beyond the individual morpheme. As Lyotard (1999; 2002) and Austin (1975) note, language emerges as a response to specific, pre-existing discursive conditions. Austin speaks of this in terms of commitment and obligation: ‘if I have stated something, then that commits me to other statements: other statements made by me will be in order or out of order’ (139). It is not just that language in certain contexts can establish and alter world relationships, but also that these bonds imply specific obligations that continue to exist after the ephemeral speech context has been completed or even forgotten. Lyotard speaks of this obligation in terms of language’s prescriptive functions:

An utterer is always someone who is first and addressee, and I would even say one destined. By this I mean that he is someone who, before he is the utterer of a prescription, has been the recipient of a prescription, and that he is merely a relay; he has also been the object of a prescription. (1999, 31)

In a ludic sense, Lux-Pain and videogames in general simulate language’s prescriptive and obligatory functions through their demand in interactive response to drive gameplay. One must, for example, push buttons or touch the DS screen to move the game forward and acknowledge that the text was received. In addition to this type of interaction, Lux-Pain presents players with moments where they must select a response from a small pool of choices. These choices are constrained to what the game provides, and the player’s ability to create alternatives outside these choices impossible. The game, in short, strives to simulate the limiters discourse places upon linguistic response through constraining interactive alternatives. The obligations and prescriptions Austin and Lyotard allude to, however, encapsulate more than ‘response’ in the semantic sense of the term, suggesting instead the role discursive systems play in pragmatically shaping the world and our rejoinders to it. The tension, then, lies with the extent to which games can govern pragmatics motivated by discursive prescriptions.

The character of Aoi Matsumura, self-described within the game as ‘the language teacher’ at Kisaragi High and viewed by the students and other teachers as a model of the profession, provides some insight into this process. She is the first teacher Atsuki meets when he arrives at school to search for leads on Silent, and her class is also his first experience with how academics operate at the school. Atsuki enters the classroom and Matsumura-sensei introduces him to other students; the bell rings and class begins. Through the dialogue box, Matsumura-sensei asks the students get out their textbooks and the following conversation begins:

Aoi

11) This is your first time, so I’ll go slow with you.

12) we have Shimazaki’s A Collection of Young Herbs.

13) Know [sic] for it’s [sic] 5/7 syllable

14) form, it’s called Japan’s own romantic anthology.

15) It’s been a popular one since last week.

16) The anthology also contains the well known First Love

17) Perhaps you’ve come across it before?

18) It’s [sic] goes, ‘You swept back your bangs…’

19) Well? Nothing?

20) This next novel should come with ease. Here’s a hint

21) It deals with the Spring, starting anew, the joys

22) and sadness of youth.Student A

23) Well, there are tons of ways to explain

24) Yeah, so should we get on to our homework as usual?Student B

25) Yeah there are.Aoi

26) Hmm … such a wonderful love as this … (Killaware 2009)

Within the classroom environment, Aoi Matsumura’s position and responsibilities at Kisaragi High amount to reading and explicating literature. Reading and even translating literature may plausibly be part of an advanced language class, and given Atsuki’s age of seventeen it is equally plausible that he has the language background to succeed in such a class. Based solely on this very small and isolated context within the game, little appears amiss; however, interactions with Matsumura-sensei are not limited to the classroom, and Atsuki frequently encounters her in various locations throughout Kisaragi City either checking up on students she is worried about or gauging the suitability of popular hang-outs where students gather. In one of these encounters, she confesses to Atsuki that she does this because ‘a teacher should protect and guide their students’. These encounters emphasize the prescriptions placed upon the profession as constructed by the internal discourse of the gameworld, but they must be read in concert with other similar discursive prescriptions to establish said world as coherent. In this case, the issue of Lux-Pain’s fluid location once again emerges to disrupt a pragmatically coherent environment.

One possibility places Kisaragi City within America, and from this vantage we can most clearly see how inconsistencies within the gaming environment collude to destabilize the gaming performance and pragmatic construction of the world. Aoi Matsumura’s specialization as evinced from the dialogue above is Japanese. Based on how she conducts the course, her pedagogy challenges students to explicate literary texts rather than study the grammatical, semantic, or phonological characteristics of the language. All of these features appear plausible, given some latitude and generosity with how the game constructs secondary education in America; indeed, from the perspectives of gaming and aesthetics, the text itself has been argued to be not a representation of the ‘real’ world but, rather, suggesting potential of how it could be (Frasca 2001). Lux-Pain offers for players’ consideration a high school where the study of Japanese amounts to a cultural immersion: in addition to the study of Japanese literature, other courses such as Reiji’s history course also revolve around Japanese cultural products. In essence, Kisaragi High amounts to an otaku magnet school.

Even with this rather lenient reading of the world Lux-Pain constructs, however, certain aspects do not add up. While Atsuki encounters a number of minor characters, he interacts with roughly twenty on a regular basis throughout the course of his investigation. Two of these characters have already been introduced: the language teacher Aoi Matsumura and FORT’s resident psychic tracker Natsuki. Other characters, such as Atsuki’s classmates and the residents of Kisaragi City, bear strikingly similar names. Prominent classmates include Akira, Rui, Shinji, Sayuri, and Yayoi; residents include characters such as Nami, Yui, and Naoto. Through these names, the question of location demands scrutiny as we are presented an America that boasts the existence of not only Japanese magnet schools but, more puzzling, an America in which the residents of at least one town reject Anglo naming practices.

This puzzling state of affairs certainly contributes to problems of immersion that disrupt the gaming experience, but in different, more subtle, ways than the obvious localization gaffes noted in the beginning of the chapter, whose disruptive epicenter can be located in purely internal linguistic mechanisms (i.e. the game as simulation). The disruptions associated with naming conventions and the location of the game’s events, however, appear to be motivated by prescriptions external to the game.

One approach to this puzzle can be found within the performative function of naming itself. According to Lyotard (2002), ‘to learn names is to situate them in relation to other names by means of phrases […] A system of names presents a world’ (44). Tracing the relations between characters provides insight into one aspect of the game’s narrative dimension – its plot – but the schema of naming, taken in conjunction with the prescriptive function of language, reflects discursive relations. Some of these are driven by the internal mechanisms of the gameworld, as the expectations of Kisaragi High’s language classes and the extra-scholastic responsibilities of teachers intimate. These two examples form part of the larger system of relations that constitutes the fictive gameworld, and through interaction with the game – obliquely referred to in ludic terms as the ‘learning curve’ – the player gleans how this system operates. Working in tandem with internally driven naming schemas, however, are terms which derive their prescriptive power from external discursive systems. The ‘America’ in which Kisaragi City is potentially located receives no description beyond the name itself, leaving the player to supply the referent with relevant pragmatic content, an attempt drawn upon the audience’s beliefs in constructing the gameworld. The problems with immersive dissonance emerge from reliance on external prescriptions to construct an internal world.

The implications of this position for the structuring of simulations are far-reaching, as the rule-based ludic aspects of language appear capable of penetrating the closed system of simulation, consequently generating a gameplay that potentially continues after the videogame ends. While specific terms may generate their meaning from within the game itself – the untranslated term shinen referring to swirling orbs of concentrated emotion, for example – the text itself cannot be constructed solely from words of this type for both practical and theoretical reasons. Much as we may push for a reading built upon what the game provides, the building blocks of Lux-Pain, when push comes to shove, are individual morphemes already empowered with signification by social decree. To create a text whose meaning derives solely from itself would necessitate the creation, essentially, of another unfamiliar set of symbolic chains that the audience would need to decipher and encode with meaning as it progressed through the game; in this sense, perhaps, playing the Japanese version with no knowledge of the language would be the closest parallel. Such an endeavor would be impractical to say the least, especially when we consider the purpose of Lux-Pain as a localized product aimed at the generation of profit and the emphasis on the JRPG genre on story and character development. Lux-Pain employs English to establish some symbolic common ground; rather than reinventing the links between the chain of signification, Lux-Pain alters specific referents whose meaning becomes ‘clear’ throughout the course of character interaction. In short, players bring discursively prescribed assumptions to the game and utilize them to navigate the simulacral waters they structure; at the same time, players may take with them referents generated in game for play in other contexts.

The gameplay of language, in other words, lies in the ability of players to divine the semantic scope of referents and actively figure out if they operate purely internally to the game or are drawn from external discourse. It continues to function after the videogame has ended, allowing for the creation of new, unique games. This last feature, explored in more depth in the next section, provides a critical dimension to approaching language in a ludic capacity by linking aspects of gameplay to ideological critique.

The immersive dissonance generated by Lux-Pain’s inability to ground itself in a stable semantic environment does not necessarily mean that this game (or other, better constructed ones) is without critical potential. The frustration evinced by the reviewers and their inability to access the game in their customary fashion reflects, in part, ideological conditioning that a ludic interpretation of language, with its ability to move freely in and out of the confines of simulation, appears exceedingly capable of engaging; this should not imply, however, that this is an easy or common task.

Critics generally focused on the ‘failure’ of the localization process in Lux-Pain by pointing to grammatical flaws that were symptomatic of a larger issue of representation. Voicing his inability to ‘get into’ the game, Acaba (2009) complains:

If that isn’t bad enough there were a few times that I couldn’t help but start snickering during really inconvenient time. When dealing with topics this mature it’s a really bad sign for you to start laughing because a girl was referred to as ‘he’ or general Engrish popping up. It kills the mood and destroys any immersion in the story which is all a game like this really has.

Acaba may be hinting at the tension between the two radically different registers of knowledge players must supply to position themselves within the game environment. Whether Natsuki wants to go to Japan or America makes a lot of difference, as most players will be much more familiar with the cultural tendencies of one location over the other, a fact that has a direct impact on how much fiddling with the prescriptions generated by signification Lux-Pain can plausibly get away with. Due to this, the existence of a city in America populated almost exclusively by Japanese nationals whose idea of language study is to read and translate ancient Japanese literature gives one pause in its sheer absurdity. But it is exactly within this absurdist realm brought about by the infelicitous meeting of our expectations between the discursive prescriptions supplied by the game and the discursive prescriptions we bring to the game that Lux-Pain points to the aesthetic potential – and here I mean the older sense of the term invested with political overtones – of embedding a game within a game.

In a very general sense, Lux-Pain can be read as confrontational and antagonistic, disrupting embedded practices and ideologies. Derived through Lux-Pain’s amateurish localization, this aesthetic impulse within the game owes its origin to linguistic issues that complicate the construction of a coherent world, either on its own terms or in its intersection with surrounding social discourses in which it is embedded. Exemplified by the game’s ambiguous setting, these linguistic issues have the potential to fashion new relationships and understandings of the world in which the player resides. Although speaking specifically about Dada, Tristan Tzara (2003) writes that art ‘introduces new points of view, people sit down now at the corners of tables, in attitudes that lean a bit to the left and to the right’ (25). For Tzara, new points of view emerge organically from the irrational, and part of his articulation of the Dadaist project revolves around breaking free from rationalist, scientific frames of thought. ‘What we need’, Tzara says, ‘are strong, straightforward, precise works which will be forever misunderstood. Logic is a complication. Logic is always false’ (10–11). Art, then, plays with the ordering and structure of the world as mapped by specific ideologies, attempting to offer alternate modes of envisioning the world predicated upon contradiction.

Lux-Pain enacts this process through language, albeit unintentionally. The world Lux-Pain presents to players certainly bears similarities to the one external to it, but inconsistencies in the performative construction of the virtual environment disrupt the gaming experience. A conflict between multiple competing constructions of the same world that ground the player’s social, cultural, and ideological assumptions in different ways emerges; instead of asking why a town such as Kisaragi City would exist in America, the more fruitful way to approach the game’s performative inconsistencies according to the aesthetic map offered by Tzara would be to ponder why America cannot have such a city. In this vein, the contradictions and confusions circulating the game express not liabilities but, rather, a new vantage from which to engage ideological networks such as nationality and identity. This approach applies equally to more polished games, although the manner in which they engage ideological apparatuses is less evident; after all, ideology operates best when hidden, and the position of videogames within the popular arena as entertainment media, coupled with a lack of linguistic ruptures to draw attention to the prescriptive underpinnings of language, obscures how they function as the potential world Tzara and Frasca note. Lux-Pain is like the friend who can’t keep a secret: its linguistic slippage reveals how language constructs more respected games.

Along these lines, then, even the grammatical and pronominal inconsistencies that are the subject of re\viewer consternation suggest ideological revelation. Similar to the case above regarding the aesthetic potential housed in the ambiguity of the game’s location, the grammatical errors often cited by the reviewers point to a breakdown in representation, a disjunction between signifier and signified that scholars have argued shape our approach to the world. Attention to language, in fact, figures prominently in Dadaist literature, where discussion and implementation of it aims at reframing the chain of signification. In the ‘Dada Manifesto on Feeble Love and Bitter Love’, Tzara (2003) glibly remarks that ‘the good Lord created a universal language, that’s why people don’t take him seriously. A language is a utopia’ (47). The polemic nature of this statement enacts the Dadaist position over language; in articulating language’s link to the divine, problems over commensurability appear all the more poignant. At the heart of Dadaist theorization on this subject beats the arbitrary nature of signification; poised against bourgeois art and academic criticism, Dada revels in incommensurability by stripping the status of the artwork of communal interpretation:

The bourgeois spirit, which renders ideas usable and useful, tries to assign poetry the invisible role of the principle engine of the universal machine: the practical soul […] In this way it is possible to organize and fabricate everything. (Tzara 2003, 73)

In dissolving, refiguring, or altering the way in which specific words are understood through either grammatical rearrangements or semantic/pragmatic reconstitutions of words, the mandate of the market to render all things equivalent and into use value becomes stymied, momentarily arrested in its course of world domination like a supervillain without henchmen.

Lux-Pain’s overlooked grammatical inconsistencies parallel the spirit of the Dada aesthetic in that the slow dissolution of referents in the game affects the cultural understandings of the words, revealing in ideological structures the potential for alternate symbolic configurations. The clearest case of this potential rests with the intermittent application of incorrect pronouns to the game’s characters, a potential bolstered by the ethnic character of their names: players face being kept in a state of flux, constantly reconfiguring their perceptions of characters as they try to ascertain with certainty which gender box they belong to. Naturally this does not happen with every character, and in many cases a given character’s gender can be based on vocal or visual cues. However, not every character is given audio or visual ‘screen time’ in every interaction. Coupled with the androgynous Japanese animation style and unfamiliarity with the gendering of Japanese names, a player must be hyper-aware of who is doing and saying what or risk confusion.

Problems over the US localization of Lux-Pain have been traced to inconsistencies between the sub and the dub facets which contribute to differing performative constructions of the game. Positioned within an analytical framework sensitive to inconsistency as aesthetic, the problem emerges due to the simultaneous existence of these features producing a performative inconsistency in the construction of the world. As discursively closed systems, simulations require that the performatives through which the world is constructed be consistent within that world, a feat which requires a modicum of suspension of disbelief. In the case of Lux-Pain, however, disbelief remains elusive due to competing versions of the world that can be traced to mismatches between the written and aural texts. This aspect is typically the focus of fan discontent, but such discourse tends to remain isolated to the grammatical realm and overlooks a deeper interpretation for fan discontent rooted in how language co-constitutes the aesthetics.

In this chapter I have argued that language should be treated as a form of gameplay driven by linguistic rules ranging from the grammatical to the semantic, sketching out how these rules intersect with, operate within, and even exceed the organizational rules imposed by the structuring of simulations known eloquently as ‘games’. In this vein I have made three arguments, although I feel that the second is more significant than others due to its larger theoretical implications for ludology as a whole. My first advocates that in the context of JRPGs, language should be treated as a component of gameplay due to its ability to prevent immersion or engagement with the text in question. My second point builds upon this claim and argues that these moments of immersive dissonance arise from both internally and externally driven linguistic rules; this is particularly significant as language appears capable of escaping the event horizon that keeps simulations self-contained and self-referential. The final argument asserted that this ability of language to persist outside the simulation (or enter it, as the case may be) offers a unique opportunity for ideological criticism surrounding a game and represents an approach not necessarily beholden to discussions of game plot.

Naturally, as JRPGs rely heavily on language, particularly stories, to carve out their identities, using them as a starting point to theorize the ludic dimensions of language may seem counter-intuitive, given the tendency in the literature to conflate language with narrative. Their status as translations, however, provides particular opportunities in this regard not commonly found in their less-travelled and monolingual brethren, and the insights garnered here can offer a basis for more generalized study of the chimeric qualities of language, particularly the contexts in which it operates as a narrative device and when it operates ludically.

Note

1 The author would like to thank his dissertation committee, and especially his advisor Timothy Havens, for their guidance and support during the drafting of this chapter, as well as the editors of this volume who exercised immense patience during the revision process.

References

Aarseth, Espen. 2004. ‘Genre Trouble: Narrativism and the Art of Simulation.’ In First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game, ed. Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan, 45–55. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Acaba, Daniel. 2009. ‘Lux-Pain review.’ GamingExcellence. Accessed 19 September 2009. http://www.gamingexcellence.com/ds/games/2166/review.shtml.

Apperley, Thomas. 2006. ‘Genre and game studies: Towards a critical approach to video game genres.’ Simulation & Gaming: An International Journal of Theory, Practice and Research 37 (1): 6–23.

Austin, J. L. 1975. How to do Things with Words, ed. J. O. Urmson and Marina Sbisa. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Original edition 1955.

Barton, Matt. 2008. Dungeons & Desktops. Wellesley, MA: A K Peters, Inc.

Baudrillard, Jean. 1994. Simulacra and simulation. Trans. Sheila Faria Glaser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Original edition 1981.

Bogost, Ian. 2007. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Video Games. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Castle, Matthew. 2009. ‘Schoolgirl Crushes and Crushed Spirits.’ Gamesradar. Accessed 18 September 2009. http://www.gamesradar.com/ds/lux-pain/review/lux-pain/a–20090401101643619005/g–2008121011456970068.

Chandler, Heather M. 2005. The Game Localization Handbook. Hingham, MA: Charles River Media, Inc.

Chomsky, Noam. 1957. Syntactic Structures. Cambridge: MIT Press.

—1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Frasca, Gonzalo. 2003. ‘Simulation Versus Narrative: Introduction to Ludology.’ In The Video Game Theory Reader, ed. Mark J. P. Wolf and Bernard Perron, 221–35. New York: Routledge.

—2010. Simulation Versus Representation. Ludology.org. Accessed 09 April 2010. http://www.ludology.org/articles/sim1/simulation101c.html.

Hymes, Dell. 1989. Foundations in Sociolinguistics: An Ethnographic Approach. 8th edition. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Original edition 1974.

Killaware. Lux-Pain. [Nintendo DS]. Ignition Entertainment: Glendale, CA, 2009.

Kuzimski, Alexander. 2009. ‘Localization: Beyond Translation.’ Accessed 1 July 2009. http://www.marlingaming.net/goldensun/portfolio/localization.pdf.

Labov, William. 1991. Sociolinguistic patterns. 11th edition. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Original edition 1972.

Lux-Pain Official Webpage. 2009. Ignition Entertainment Ltd. Accessed 18 September 2009. http://www.luxpain.com/.

Lyotard, Jean-François. 2002. The Differend: Phrases in Dispute. Trans. Georges Van Den Abbeele. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Reprint, 6th.

Lyotard, Jean-François, and Jean-Loup Thébaud. 1999. Just Gaming. Trans. Wlad Godzich. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

McLuhan, Marshall. 1994. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Cambridge: MIT Press. Original edition 1964.

Nagidar. 2011. GameSpot Forums – System Wars – JRPG’s are not RPG’s. Accessed 21 February 2011. http://www.gamespot.com/pages/forums/show_msgs.php?topic_id=26428529.

Searle, John Rogers. 1989. ‘How Performatives Work.’ Linguistics and Philosophy 12 (5):538–58.

—1995. The Construction of Social Reality. New York: The Free Press.

Shau, Austin. 2009. ‘Lux-Pain Review.’ GameSpot.com. Accessed 19 September 2009. http://www.gamespot.com/ds/adventure/luxpain/review.html.

Toaplan. 1992. Zero Wing. [Sega Mega Drive]. Sega: Brentford, UK.

Tzara, Tristan. 2003. Seven Dada Manifestos and Lampisteries. Trans. Barbara Wright. 5th edition. New York: Calder Publications. Original edition 1977.

Venuti, Lawrence. 2008. The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation. 2nd edition. New York: Routledge. Original edition 1995.

‘Video Game Review: Lux-Pain for Nintendo DS’. 2009. The Anime Almanac. Accessed 18 September 2009. http://animealmanac.com/2009/04/10/video-game-review-lux-pain-for-nintendo-ds/.

Wolf, Mark J. P. 2002. The Medium of the Video Game. Austin: University of Texas Press.