Chapter Five

Long Distance Migration

5.1 The Migratory Instinct

Humans have always been restless and mobile. Even the movement of early homo sapiens out of Africa was motivated, we presume, by a need to acquire more food, clothing and peaceful surroundings. In modern terms, we call this a larger and more stable source of income. Nomadic peoples from the earliest times wandered in direct response to the need for additional pasture to keep their growing flocks of sheep and goats (resources). Great migrations took place more or less continuously.1 For instance, the Celts’ westward migration within Europe in pre-history was a likely response to economic and political pressure at their eastern border. The citizens of imperial powers such as the Egypt, Greece and Rome spread to the empire’s hinterlands; many stayed. In time, these imperial countries were beset by great barbarian invasions. The Visigoths, in the 5th century, moved westward within the Roman Empire, sacked Rome and eventually claimed land in southern Europe. Other barbarian sweeps followed. The Huns were, within several centuries, followed by the Mongols from Central Asia who not only spread westward but eastward into China where they established their own dynasty (the Yuan). Religion presented a motivation, or pretext, for expansion and subsequent settlement, such as the Muslims in the 8th and 9th centuries moving through North Africa into the Iberian Peninsula and East Africa, and the Spanish moving into large portions of South America in the 16th and 17th centuries. On a smaller scale, the emigration from England and Holland to the North American colonies in search of religious toleration had, like all others so motivated, both an economic motivation and consequence. The motives for migration are seldom uni-causal. But, whether part of a voluntary international movement, expelled, or migrating for other reasons, choices had to be made.

For some, the choices were limited or essentially non-existent. There is a rather touching statue just outside Liverpool Street Station in London. It depicts a group of several children, of various ages, all looking slightly lost. Each has a suitcase and a personal possession, a toy, doll or book. The statue is a memorial to the “kinder transport,” the Czech Jewish children whose anxious parents sent them to Britain by rail in 1939 to avoid repression and the coming holocaust. It also commemorates those people who engineered the transport at some danger to themselves. Wars were not the only cause of flight; as we well know there have been many types of human action, and indeed inaction, that caused widespread human suffering and death for those left behind. Unfortunately, memorials to peoples bravely fleeing to safety are common; for example, there are the recently erected memorials in Helmsdale, Sutherland, to the Scottish Highlanders forced off their crofts in the 18th and early 19th centuries and into the migratory stream and the one in Grosse Île, Quebec, to the starving Irish who landed at Quebec in the famine years of 1847–1849. There are many other flights to safety that are not memorialized – but remembered. The pogroms aimed at displacing European Jewry in the 19th and 20th centuries are celebrated in Yiddish literature for the resilience of those displaced.

In less traumatic circumstances, there were times when the basically rural population of Europe migrated to the towns with increasing frequency: as trade and port cities grew, as administrative centers evolved, and as industries such as the woolen trades became specialized. Yet, it was not until the early modern period (the 17th and 18th centuries) that the structure of the European and North American economies started to change systematically from agriculture to a more diversified industrial/service base. The movement of people became part of that change. It had three main components:

- the rural-urban shift;

- regional (internal) migration; and

- long distance or international migration.

The industrial transition loosened the population, or parts of it, from its traditional rural roots by the changing demand for labor. As reflected in the growing discrepancy between agricultural and non-agricultural wages (incomes), this labor flow proceeded more or less continually until the present day. In OECD countries and some others, however, it has slowed both in absolute numbers and proportional terms as the agricultural sector has become too small a part of developed economies to be the source of many migrants of any sort.

Regional migration within a country, including the rural-urban shift, and international migration are closely related historically. To take one example: farm laborers in Southern Italy decided to move northward to Milan in pursuit of higher wages. Once the question of migrating had been introduced, some would now consider, and could afford, a longer migration from rural Italy to, say, Boston or New York. So the decision to be an international migrant can be a two-stage process. An individual may be a regional migrant first and subsequently an international migrant, presumably based on acquiring information and amassing the funds to finance the international move. Naturally, the timing and intensity of flows varied with both the economic conditions of the migrant-receiving and migrant-donor countries. These are often referred to as the “pull” and “push” forces of migration respectively.

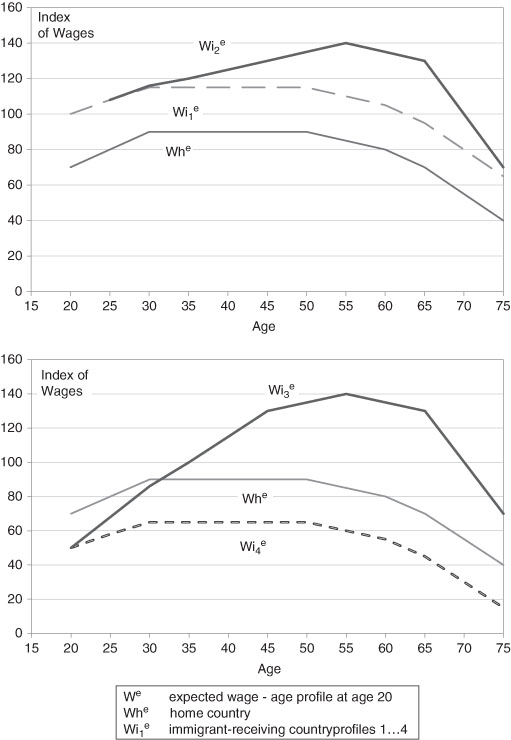

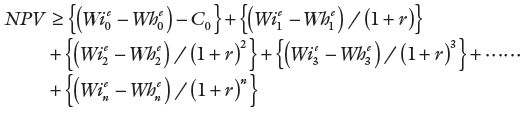

The most potent of these forces is the “better living” that international migrants expect to achieve in the country to which they go. This is typically expressed in terms of wages or incomes – the assumptions are that all income is earned income and that the immigrant has a fixed level of human capital or education. Figure 5.1 shows several examples of the expected wage profiles for a 20-year-old hypothetical immigrant and their wage profile at home.2 The home wage-age profile is relatively flat reflecting either a low level of skills or a lack of rewards with experience – in labor markets today such a profile would generally be predicted for an individual with a low level of education and no prospects of job advancement. However, for this potential immigrant the wage profile may not simply be higher but take on a different shape Wi2 e. That is, the wage continues to rise and peaks much later in life due to job advancement available only in the new country of settlement. If the expected (ex ante) wage is the realized (ex post) wage, the migration is clearly successful. But what if the realized wage profile is lower than expected? The migration might still be successful if a wage profile differential between that of home and immigrants-receiving country is positive and compensates for all the costs of migration. The second panel of Figure 5.1 shows alternate expected wage profiles from migration. One is wholly below the home wage-age profile and is unlikely to induce migration. The second, and by far the more interesting and historically more representative case, shows a wage-age profile that is initially below the home wage but rises above it at some later age, here about age 30 (Wi3 e). The current wage would not induce migration by itself. However, the higher wages beyond age 30 would be a stimulus to movement if their future value is taken into consideration from the outset and offsets the early wage losses. And because these are future values, this requires calculating the familiar discounted present value.

Figure 5.1 Expected Wage Profiles by Location.

In order to induce migration the present value of the alternatives must be positive and take into consideration the (fixed) costs of migration. To this we might add the value of the immigrant child. Even today when asked the reasons for migration the immigrants will often respond that they migrated for the sake of the children to have a better life. The cost of international migration may be too high to compensate for the present value of the expected wage differential (income) and thus migration will not occur. It is, after all, the net present value from migration that is the key to the decision to migrate. Not only are there the costs of transport, plus any costs associated with financing them, but there are the costs (gains) of i) asset disposition; and ii) uncertainty. The disposition of assets (in the home country) and their replacement (in the immigrant-receiving country) is fraught with uncertainty. These assets include personal possessions and housing but may also include the cost of earning assets such as sewing machines or, if the international migration is a rural to rural one, a farm disposition and acquisition. This asset transfer problem is going to make older individuals more cautious about moving as they have more assets, and therefore more to lose, than younger potential international migrants – the less wealthy.

There are also the less adventurous among us and those who hold a special affection for the society and place in which they currently live, the so-called psychic benefits derived from remaining in place. Most people ignore or resist the temptation to move or are unaware of the benefits to becoming international migrants. Thus social scientists seeking to explain a flow of immigrants are looking for causes at the margin. First, there may be ignorance of the fact that a wage differential exists between countries especially as this differential necessarily is an average. Second, even when the average differential is known with some certainty, there may be uncertainty about where any one individual (the decision-maker) may end up on the wage distribution in the receiving country. Third, the cost of international migration may have simply been too high to compensate for the expected higher wages (income) - all appropriately discounted.3 Clearly, few did such calculations but rather asked questions that amounted to getting the same information: Will I be better-off? Will I be better-off in the long run? How much better-off will I be? Will I have friends or family there? Is it true, as I’ve heard, that New York (or Iowa, Manitoba, Christchurch, Woolongong) is really quite nice?

When labor migrates from a lower to a higher wage area, it changes the supply of labor in both places. An increased supply of labor pushes wages down in the one area, and the decline in the labor supply pushes wages up in the other. In the economic theory of trade, this flow of labor with its international equilibrating wage tendency is called factor price equalization. Economic historians look for real wage convergence (where the nominal wage of labor is adjusted for the cost of living at the chosen locations).4 Even if labor were immobile between economies, international trade would itself induce factor price equalization. The reason for this is that countries would specialize in the production of commodities that employed relatively more of the abundant factor within their own economies, thereby conserving on the use of the scarce, and more expensive, factor. This theory, the Hecksher-Ohlin model of trade, predicts that a country’s exports will embody the country’s abundant factor of production.5 Even without a flow of international labor or other factors of production, there should be a convergence of factor prices between countries. The historical problem is that, when we look at the massive migrations of the 19th and 20th centuries, both of these economic trends occurred. The international flow of goods and services and the increased flow of labor were not substitutes, but complements, in the process of economic growth. Although far from complete, both the convergence of real wages and that of commodity prices were the hallmarks of the increased globalization.6

International migration was also accompanied by a flow of capital. The countries of Argentina, Australia, Canada and the United States, for instance, borrowed massively from Europe in the long 19th century (to World War I). Much of the capital originated in Britain and was financed out of the positive balance of payments on current account. In turn, a large share of this capital was used to finance expansion of the transport infrastructure – particularly the large, transcontinental rail projects in these countries – and the growth of cities and towns. In North America, rail expansion onto the Great Plains and Prairies brought huge amounts of land into production. The expansion into Russian Siberia also brought new agriculture and new settlement as a result of an eastward expansion. In other areas such as Europe, China, India and Africa, railways encouraged new and higher productivity uses of land. Throughout the main phases of demographic transition, land, far from being a fixed factor of production, was rapidly expanding at the extensive margin, as were capital and labor. The demand for labor was shifting upward (outward) causing the wage convergence to slow down (if not reverse itself) from time to time.

5.2 Who’s In and Who’s Out

Historians face a difficult problem, one that persists even in today’s world, and that is counting the numbers who entered into the international migration streams. For the period before the modern age of record keeping, which we may date to the mid-19th century, all counts are based on the ingenuity of historians using local historical knowledge, shipping and port records, military records and incomplete censuses.7 The reason such censuses exist is the same that the Romans used: to determine who is to be taxed and to have a ready roster of (loyal) fighters available for local duty. Even when record keeping became more thorough, the count of immigrant arrivals was still incomplete, missed counts and “illegal” immigration notwithstanding. Also, countries were generally more concerned about the people who entered than those who left. Even today most countries do not have a formal process of counting permanent departures – the emigrants. (Modern OECD governments go to great lengths to estimate, not count, the emigrants through tax records, government benefits records and the like.) Unfortunately, for the counters, we only have a census at regular fixed intervals to verify the numbers (see Chapter One). By comparing the censuses over time, we measure the change in the size of the population. New population additions are made up of those born and new immigrants, both of which can be counted by the census. There are only two exits. The first is death, which we can also count from death registration records. The other is emigration which becomes the residual, balancing number. Of course, we have to account for those who are born and new immigrants who have been registered between the censuses in one country and then either die or migrate to another country.

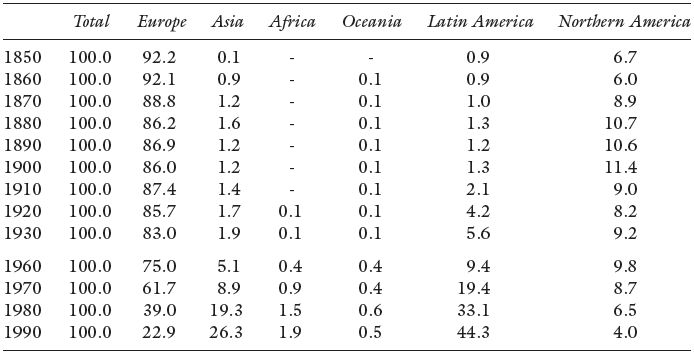

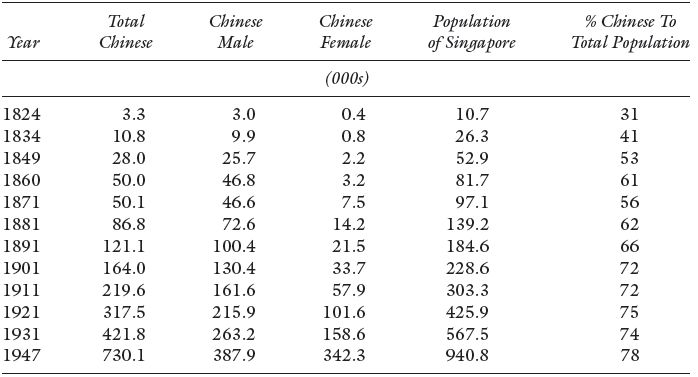

Table 5.1 Region of Birth of the Foreign-Born Population of the United States: by Percentage, 1850 to 1930 and 1960 to 1990.

Source: US Bureau of the Census (1999) The Foreign-Born Population of the United States, Table 2, Internet Release, 9 March 1999.

Every emigrant should be an immigrant somewhere. Unfortunately for the historians, there was not a systematic way in which immigrants were recorded. For instance, if we try to account for the substantial emigration from Canada by looking at the immigrant counts in the US (we know that overwhelmingly Canadians migrated to the US prior to 1945), the numbers are not even close. A Canadian may have been born in the UK, carried to Canada by its immigrant parents, spent almost their entire life in Canada, and then as an adult emigrated to the US. When that person entered the US, he or she was recorded as an immigrant from Britain because of their place of birth. Each country had its own standards and thus immigrants were recorded by some as: from their place of birth, last country of residence, last country of permanent residence, or citizenship. So the historical US records of immigrants will only note those who were Canadian-born and not our imagined British-born Canadian emigrant. Modern records are more complete (see Table 5.1).

The flow of immigrants on a year-to-year basis contributed to the stock of immigrants measured in the censuses. Thus countries have a stock of immigrants that reflects the cumulative inflow of past immigration, net of deaths and departures. The stock is defined to include anyone living, no matter what their current citizenship, who once had been an immigrant. Thus, the Canadian and Australian immigrant stocks are dominated by the British and Western Europeans, despite the fact that most of their immigrants in recent years are of Asian and South Asian origin. It takes time for the stock to adjust, but it will do so more rapidly in the near future as the British immigrant stock is an elderly one. Until recently (the 1980s) the same was true of the US where the stock of immigrants was largely of European origin. However, the flow of immigrants to the United States has recently been dominated by Latin Americans and Asians, and is of such numbers, that it has overwhelmed the stock resulting from the immediate post-1945 immigration boom which was largely European.8

5.3 Migration of the Unfree

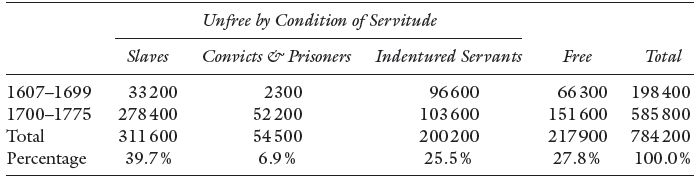

During the US colonial period (1607–1775) there were over three-quarters of a million immigrants. A full 72.2 % of these immigrants came in some form of bondage – see Table 5.2. Black slaves from Africa were by far the most numerous, but there were also convicts, prisoners and indentured servants mostly from Britain. The free voluntary immigrants to Colonial America accounted for only slightly more than a quarter of the total in the years leading up to the American Revolution.9 But North America (including the Caribbean) was far from the only destination of the unfree: South America accounted for the largest number of transported African black slaves leaving an indelible imprint on the population. Prisoners and convicts were also shipped to Australia, but at a different time.

A. Slaves

In pre-modern history slavery was a relative common condition. Most ancient peoples kept slaves. Slavery could be a perpetual condition and inherited by children or it could be limited to the lifetime of the individual. The Persians, Greeks and Romans typically enslaved those whom they conquered. These were not necessarily different people, just enemies. The original purpose of slavery was to remove a population from its home (and source of income) so that it could not take up the conflict again. However, slaves also provided labor that did not require the payment of wages, but it was not costless. Classicists insist that slaves were a consequence of war, not a cause of it. While this may be true, the ratio of slaves to freemen in ancient Athens was at least 2 to 1 and maybe as much as 3 to 1. This suggests that replenishment of the stock of slaves was necessary from time to time to maintain it at existing levels. As the conquests became more distant from the homeland, the enslaved were naturally more distinct in terms of customs, languages and religions and could be regarded as inferior. Therefore, in the eyes of the enslavers, their condition was justified. The Romans shipped large quantities of slaves from the periphery of their empire to Italy to work the stone and salt quarries and row in the galleys (ships). But, the Romans also employed slaves as domestic servants and, on occasion, in highly responsible positions. Greek slaves were particularly prized.10 As empires expanded more and more, slaves were transported long distances and became an important element of the human migratory stream.

Table 5.2 Immigration into the US during the Colonial Period by Legal Status and Condition of Servitude.

Source: Adapted from Fogelman (1998), Table 1.

NB: rounded to the nearest 100.

Includes political exiles and kidnap victims as prisoners.

From the 9th to the 18th century, for instance, people were rounded up in the Caucuses and Eastern Black Sea regions and sold into slavery. They were then marched to various points of the Islamic empire. Known for their fighting ability, the captives were compulsorily converted to Islam and mustered into the armies of the caliphs. Clearly an incentive was needed and that was a promise of freedom (manumission) at the end of their period of service. The Mamluks, as they were known, became a formidable fighting force sometimes supplementing armies of non-slaves and sometimes being the entire fighting force. Originally mustered by the Assabid Caliphs of Turkey, they frequently assumed local power themselves after the caliphate collapsed in various regions as far flung as western India to Egypt. In Egypt, the Mamluks became the ruling elite in the 13th century and held power for 300 years in Cairo, all the while continuing to purchase more Mamluks (in the tens of thousands) for their armed forces.11 The Mamluks were renowned for the defeat of the Mongol armies in 1260 – clearly they were slaves of a different sort.

Yet there is nothing in the sad history of the institution of slavery to compare to the massive movement of black slaves from Africa to the Americas. Where it existed in the new world, it was generally profitable and an economically viable institution.12 Slaves were principally used as manual labor in the tobacco, rice, sugar and cotton plantations of the West Indies, South America and what became the US. As such slavery existed until the middle of the 19th century. However, the trade in slaves, as distinct from their ownership and use, was made illegal in the early part of the century due in great measure to the highly charged campaigns of the English reformer William Wilberforce. These campaigns aroused public indignation on both sides of the Atlantic. As a result, Britain passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act in 1807 although slavery itself was not made illegal in Britain and its Empire until 1833. In the year following the British 1807 act the United States legislated:

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That from and after the first day of January, one thousand eight hundred and eight, it shall not be lawful to import or bring into the United States or the territories thereof from any foreign kingdom, place, or country, any negro, mulatto, or person of colour, with intent to hold, sell, or dispose of such negro, mulatto, or person of colour, as a slave, or to be held to service or labour. [original spelling].

[Public Statutes … of the United States of America, Statute II, Chap.XXII, 2 March 1808.]

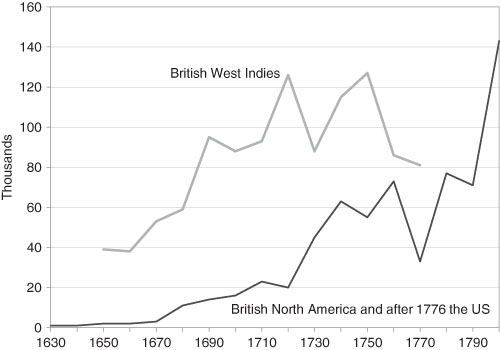

But, only the end of its Civil War in 1865 brought an end to black slavery in the US.13 Spain and Portugal finally agreed in 1815 to the abolition of the slave trade within five years. France temporarily outlawed slavery at the time of its Revolution, but slavery was reinstated and lasted there until 1848. Likewise, Holland did not ban the holding of slaves until the 1840s. It has been estimated that altogether approximately 9.5 million individuals were transported as slaves from Africa to the Americas from the 17th to the early 19th centuries.14 Most slaves were destined for the West Indies and Brazil. A minority went to the other South American countries, and only about 10 % of those were landed in the British North American colonies (as distinct from the British West Indies) and later the US (see Figure 5.2). The journey to the Americas from Africa has been the subject of much historical inquiry just as it was a highlight of the Wilberforce abolitionist campaigns: the wretched conditions of transport by sea, the over-crowding and unsanitary conditions. While the abolitionists of the day evoked tearful sympathy describing these conditions, the voyage characteristics were actually fairly similar to those experienced by the crews and fare-paying passengers. Of course the slaves suffered indignities that the fare-payers did not: the degrading human bondage and rape of female slaves. But, there were actual incentives for the slavers to keep the slaves alive and healthy as the value of the slave was realized at the end of the voyage. The carrier with fare-paying passengers had no such incentive which, at the margin, might reduce mortality on the voyage. Certainly, the Middle Passage, as the various mid-latitude trans-Atlantic sailing routes from Africa to the Americas were collectively known, never produced the high rates of mortality experienced in the North Atlantic during the Irish Famine years of the late 1840s (see later).

Figure 5.2 Import of Black Slaves to the British West Indies, British North America and the US, 1630–1800.

Source: data from Carter (2006), US Historical Statistics, Table Ad3–15.

Note: British North America includes only the British Colonies that became the US.

In general, the mortality of slaves on the Middle Passage declined from the high figures in the 17th century at about the same rate as the deaths of immigrants on the North Atlantic – from about 16 % in the late 17th and early 18th centuries to rates about 7.7 %.15 A large part of this decline was due to the decreased length of voyages, the increased efficiency of vessels and the scale economies of slave gathering – the latter made voyages shorter as ships no longer undertook coastal cruises to pick up slaves at the various way points. Some routes on the Middle Passage continued to be more dangerous in large measure because of their long voyages. By only measuring the mortality on the voyages we overlook the long period of captivity before the trans-Atlantic shipment.16 We conjecture, in the absence of quantifiable evidence, the mortality in this period was high. If the deaths before leaving Africa were equal to those on the voyages, the slave migration in total probably killed one able bodied male for every three enslaved. The toll may have been higher among women and children.

B. Convicts and Indentured Servants

Apart from slavery there were other forms of migrant bondage, although not ones that usually resulted in a permanent alienation. From time to time in the 17th century prisoners and convicts were sent from Britain to the British North American Colonies (later to Australia). The object was simple: remove the most troublesome of British society, a classic push force. James Butler, a late-Victorian historian, noted that many of these were political prisoners including those captured in the English Civil War, Cromwell’s Wars against the Scots and the Irish, and the various uprisings of the period.17 However, in 1718, in the aftermath of the Jacobite Rising of 1715, the policy of shipping undesirables to the colonies became systematic in English law; the passing of the Transportation Act permitted such a sentence.18 Most of those transported were serious felons having committed more than one offence. A significant minority was guilty of capital crimes such as counterfeiting, kidnapping, highway robbery, manslaughter and murder. There were about 160 crimes punishable by death, but an individual might be allowed to live on condition they transported themselves out of England. Capital crimes, when leniency was exercised or a pardon from the death sentence was granted, were typically punishable by a seven-year, a 14-year or, on occasion, a life sentence. The labor service of the convicts and prisoners were auctioned off in the colonial markets. Since convict laborers could return to Britain at the conclusion of their sentence, and runaway convicts often made it back as well, it is uncertain how exactly they added to the population. Most who had served their sentences probably stayed in the colonies, albeit in a different area than their penal service. Because of the social odium, they sought out the anonymity of the frontier or the growing towns. Once their sentences were complete, the ex-convicts were no more likely to be guilty of offences than the general population.19 Although most colonies received shipments of prisoners (and there were objections to them in several colonies), the favored destination was the tobacco-growing areas, particularly Maryland, Virginia and the Carolinas.

With the Revolution the transportation of convicts to the US came to an end. However, the role of recipient was quickly taken up by Australian penal colonies, Botany Bay and Van Dieman’s Land. They were different from those of America in that they were established in a land with very few free immigrants in the early settlement period – and many of those were government officials who did not remain. The result was the transported prisoners contributed more to the growth of the Australian population than prisoners had to that of the US. In the 1820s more than half the Australians were prisoners-bondsmen. Even by 1841 over 20 % still were in bondage – new shipments and those serving out their terms.20 This does not include those who completed their sentences and remained in Australia.21 Nor does it include the children of the original prisoners, and their further progeny. Perhaps the large number (and proportion) of the population that originate from convict labor accounts for the Australian retrospective pride in these tough antecedents.

Unlike the case of the North American colonies where there was a ready demand for labor as household servants and agricultural workers, there was no such exuberant demand in Australia. Wasn’t the transportation of prisoners halfway around the world not a rather expensive way of getting rid of the troublesome elements, especially if there was little existing demand for their services? With the loss of the Thirteen Colonies there were few alternative places to send convicts that were relatively secure. Plus, there was another motive. Britain was in the throes of rebuilding its empire, and peopling the continent with British folk, albeit the more desperate ones, was part of the strategy.

Indentured servitude was the device developed to increase the migration of white European workers to the labor-short North American colonies. Almost as many people arrived in the colonies as indentured labor as arrived as free citizens. Researchers have documented how well-organized the markets were for indentured servants.22 An individual would contract with a ship captain or merchant to work for a specified number of years (usually between four and seven) in return for transportation across the Atlantic plus specified payments (usually food, clothing, housing, or perhaps some education or training in a craft or skill). Also specified was an amount of money or land to be paid when the contract was successfully completed, largely to help assure that the contract would be successfully completed. There was a good deal of bargaining between potential servants and those contracting with them. The holder of the contract in England paid the cost of the trip. When the ship arrived in North America, the contracts (and the people) were sold, usually onboard the ship. The purchase price, which depended upon the servant’s age, sex, and skills, was equal to the realized cost plus about a 50 % markup.

When the colonies adjoining Chesapeake Bay first discovered that crops were most profitably grown under a plantation system, the demand for indentured servants soared. A sample of over 20 000 indentures taken from surviving ship records suggests the majority chose to go to the Chesapeake. These individuals were predominantly young males in their late teens and early 20s who were farmers, artisans, (unskilled) laborers, and domestic servants.

For example, Walter Gibson, a ship’s master and merchant of Glasgow, published a broadsheet in 1683 in which fares for the voyage to Carolina were listed at £5 per adult. Once settlers had reached the colony each was eligible to apply for 70 acres of land from the colonial government for a fee of one penny per acre. There were terms, not onerous, that had to be fulfilled. But there was another pitch in this advertisement:

To such as are desireous to Transport themselves to the said colony of Carolina, and are not able to pay their Passage; If they be Tradesmen, who have past their Appentiship in any Handy-craft; The said Walter Gibson is content to Transport them on his own Charges, they obliging themselves to Serve him three years, during which time he will furnish them sufficiently with Meat, Cloaths and other necessaries. At the issue of the time of their Service, they are to have settled upon them and their Heirs from the Government, each of them fifty Aikers of Ground, they paying one Penny Sterling per Aiker yearly … [Original spelling retained.]

Gibson (1683), Proposals, 1.

Each person in the family, including servants, was eligible to receive the same land allowance. Folk without a trade had to serve Gibson for four years and settlers under 18 had to fulfill a service period of five years but were able to apply for the same land allocation on the same terms.23 Indenture contracts had status in courts of law, and servants could appeal to the courts for violations of their rights.24 Once the indenture was completed, the former servant was a member of the free population; children born of indentured servants during servitude were born free.

A related group was known as redemptioners. Most came from Germany and had a slightly different status than the English indentured servants. While English servants usually came over alone, the Germans came in families, bringing their own supplies and movable property with them.25 The ship captains that brought them generally allowed them time to arrange payment for their passage after arrival.

The rather abrupt shift from reliance on white servants to black slaves at the turn of the 18th century was attributed to the wars of King William III and, especially, those of the reign of Queen Anne. These wars reduced the supply of prime-aged males, which in turn reduced contract lengths, thereby increasing the effective price.26 With the return of peace, the market for indentured servants revived, but not to its previous numbers. On average, black slaves cost more than white servants because their “contract” to the buyer was for a longer time period. Thus, slaves tended to be more profitable to those involved in their transport and initial sale.

European immigrants wanted land for themselves, and there was unlikely to be a sufficient supply of indentured servants to meet the labor demand in the South. Although Virginia and Maryland were major destinations for indentured servants in the 17th century, by the 18th century, when potential servants had more choice, they chose to avoid the Southern colonies. Why this was true is not entirely clear. Most 18th-century white immigrants went to Pennsylvania where land was readily available and the institutions were liberal. But the same could be said of Virginia. The temperature-humidity mix of the middle colonies was as oppressive as that of the southern ones. Jefferson’s comment that, “In a warm climate, no man will labor for himself who can make another labor for him,” is just as true for residents of other climates.27 The fact that the South has warmer winters than the North should have made it attractive to Europeans. Further, if wages were high enough, they could “make” others labor.

Near the end of the 18th century, white servitude was declining in competition with wage labor. In the free market, white skilled workers were able to negotiate wages that were higher than the comparable real income derived from a contract of indenture. The rising demand for labor drove up the price of non-free white labor compared to that of black slaves leading to a decline in servitude. Nonetheless, in 1787, when the US Constitution was being written, white servitude still had to be taken into account, and it lingered on. A study of German redemptioners concludes the end came about 1820.28 Only 18 indentured servants arrived in 1820 and only 19 in total during the following 10 years. Most of these were children.

Concurrently, US judges began to refuse to imprison people for debt. If the indenture contract was not enforceable, it lost value. Negotiated wage contracts were more efficient, and any break by the employee before the contract expired released the employer from the obligation to pay wages.29 The other obligations of indenture (e.g., room, board, clothing, medicine, education in a trade, and payment at the end) did not apply to wage labor. However, as indentures disappeared, turnover costs increased, especially for employers who required more labor than their families could supply. When the cost of searching for workers and the cost of going without labor during a critical period was high, employers (i.e., Southern plantation owners) were attracted to slavery to mitigate these costs.30

C. Child Migrants

There were other forms of near bondage in immigration history, although few were as touching as the case of the “home children.” Beginning in the third quarter of the 19th century, there was a philanthropically inspired and managed movement of children from Britain to the “white” colonies and dominions. The home children were orphans, abandoned children, and other impoverished youngsters from Britain. Under the supervision of guardians, they were collected from the orphanages and shipped to Australia, New Zealand and Canada. The children were often referred to as “Barnado Children” after the principal charity active in securing better lives for the youngsters. It was classic Victorian “do-goodism.” The scheme continued in operation into the 1930s (we have abundant details from the shipping records.)31 For the most part, these children were sent to the farming districts of older settlement, those districts where the fertility rates were low because of the aging population – as seen in Chapter Four. In total, somewhat over 100 000 children were shipped from Britain to Canada under this scheme. Some of these children did indeed enjoy better lives. They were given some education, tutored in farm and domestic skills, and were more or less adopted into the family to which they were sent. Others were sent to farms where they were treated as chattel labor under brutal conditions. It was, at best, a scheme with mixed human results. Surprisingly, a similar scheme between Britain and Australia was instituted after the Second World War and lasted until 1967. It too had very mixed results.

5.4 The Atlantic: Waves of Immigration

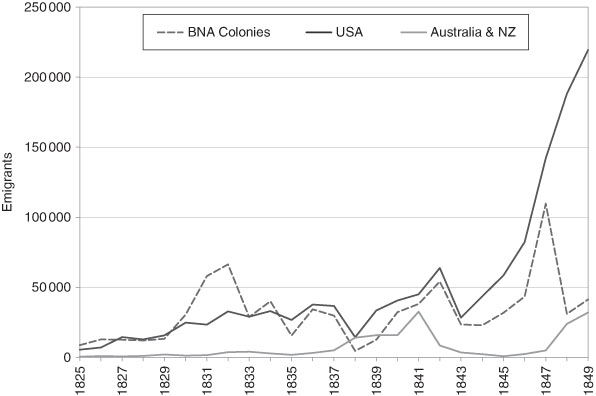

The years between the American Revolution in 1776 and the defeat of Napoleon in 1814 were ones of turmoil in the international trading economy and the small, but steady, flow of trans-Atlantic migrants was similarly interrupted. With the restoration of peace in the early 19th century the trans-Atlantic component of international migration grew to such unprecedented heights that economic historians have labeled it the “age of mass international migration.” Between 1815 and World War I approximately 55 to 60 million moved from Europe to North and South America.32 The flow of immigrants into North America in the decade after 1815 was initially much the same in character as in the 18th century: they came mainly from England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland with a sprinkling from Germany. But the volume was different, higher. Depression in British agriculture, demobilization of the armed forces, the re-alignment of British industry to peacetime conditions, and growing urban unemployment caused massive dislocation. While the fall in the cost of passage played a role in making emigration from Britain more attractive than earlier, it was the capacity that the ships now offered that made mass movement possible. Between 1825 and 1850 more than 2.25 million British emigrants left for the British North American colonies and the US – see Figures 5.3 and 5.4. These included the many Irish who left what was then Great Britain and Ireland (see Diasporas later in this chapter).

Immigrants Arriving at Ellis Island for Processing

Much of the great flood of pre-1914 Migration to the United States entered through the Ellis Island Immigration Station.

Source: Detroit Publishing Company Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division Washington.

Figure 5.3 Annual Emigration of the British by Destination, 1825–1849.

Source: Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioners data from The Illustrated London News, Saturday July 6th 1850.

BNA Colonies: Upper Canada, Lower Canada, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland, and the British West Indies.

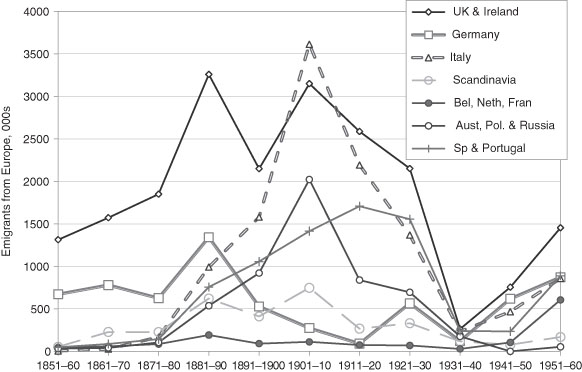

The emigration from Europe to the “New World” had its distinct ethnic characteristics. In the years before the US Civil War the sources of immigration expanded to include a large flow of Germans whose instincts to enter the migratory stream were heightened by the unsuccessful Revolution of 1848 and its chaotic aftermath. At about the mid-century mark, the now substantial flow accelerated. The Germans were followed by the Scandinavians. As the century wore on the western Europeans were joined by, first, the southern and then the eastern Europeans. By the beginning of the First World War, the majority of immigrants were non-English speaking. The broad features of this migration were shared with British North America (Canada) but with different timing. The Spanish and Portuguese also entered into the trans-Atlantic migration, but they went principally to South America (Argentina, Chile, Brazil and Uruguay). Spanish emigrants in particular rejected the lure of the US, but, drawn by culture and language, they preferred the Latin south (98 % of all emigrants prior to 1914).33 But many Italians and British also added to this flow, especially that to Argentina and Chile. The Italians had specific geographic preferences that changed quite dramatically about 1900. From 1876 to 1900 for every Italian who went to North America more than two found a home in South America. From the turn of the century to the First World War, however, the flows changed destinations with 2.4 Italian immigrants now going to North America for every one going to South America.34 This changing flow mirrors the changing pace of economic growth in the respective hemispheres.

Figure 5.4 Emigration from Europe by Decade, 1851–1960.

Source: Mitchell (1998) International Historical Statistics: Europe, 129 – see General Sources.

Notes: Figure refers to emigration to countries outside of Europe. Scandinavia is: Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Germany after 1941 includes only West Germany. Netherlands excludes emigration to the Dutch Overseas Colonies. The UK figures date from 1853 and until 1870 excludes the direct emigration from Irish ports. Some of the data that overlap World War II are truncated.

Immigration to “lands of new settlement” before 1914 has often been viewed by historians as happening in distinct waves, most importantly by Brinley Thomas and Arthur Lewis.35 Since these waves can be characterized by the new groups entering the migratory stream, sometimes as a majority, they raise a critical question: why do they become trans-Atlantic migrants in numbers at a particular period or date? The answer, anticipated earlier in this chapter, is that the historical process is dependent on dislocation in the home country. In some cases, the dislocation was caused by calamity. Most usually, however, it came about because of newfound economic strength in the home country, albeit modest. If the home economy is a traditional one with little change in the structure of employment, by industry, only a few individuals, at the margin, will become migrants. When, however, the home country begins to industrialize, there is an internal reorganization of labor markets in response. Labor moves from the traditional economic activity to the expanding sector. Attracted by higher wages reflecting a higher marginal product of labor, the workers must relocate within the country to take advantage of the higher income possibilities, rural-urban and inter-regional migration. There is a long-standing debate among economic historians about whether emigration and internal migration are positively or negatively related. The evidence largely supports the positive relationship.

Information, too, begins to flow more widely and abundantly. Shaken from their traditional roots in agriculture or low-productivity industries, labor becomes more open to the prospects of international migration. International migration was very often a two- or multi-stage process. So, for example, we find the Italians cast themselves into the international migratory flow just as the Italian economy shows signs of economic reorganization and real income per capita growth in the late-19th century. Thus, the background conditions of the waves of trans-Atlantic migration were the emergence of modern economic growth in the home countries. Waves of immigration, however, cannot go on with the same or growing intensity. It is the home economy “wage effect” that puts on the dampers. Real wages at home reacted to the loss of labor through immigration; they also responded to the continuing change of the structure of the economy in the home country.36 The international migrants expected the real wage differential between the donor and host countries to narrow.37

For potential immigrants, the attractive forces of North and South America in the years before 1914 did not send out steady signals. The frontiers were expanding westward. The frontiers drew in-migrants, both domestic and international. Some responded to the free farm land or its low price. After the US Civil War was over the provision of the Homestead Act (passed in 1862) had effect, and there was a flood of migrants to take advantage of its grants of free land. The US and Canadian railroad (railway) companies actively promoted the land they acquired from their governments.38 The Canadian frontier settlement lagged behind the US expansion by about three decades (and this fact was itself instrumental in the cycles that were generated). However, the gains (economic rents) were not simply in agriculture. They were in mineral industries and in processing the products of agriculture (meat packing, grain milling) and, importantly, shipping. Transport was one of the keys to the westward expansion, a necessity to exploit the frontier gains. The US and Canada built canal systems, the most significant were the Erie Canal and the Welland Canal, in each country respectively. The Erie linked the western regions, of the day, to the main export market in New York. The Welland linked the western Great Lakes to Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River and the Oswego Connector of the Erie. Canal building was replaced in the 1840s and 1850s by railroad (railway) building, and after the US Civil War the rail network became a trans-continental one. The relevant feature, for our purposes, was that canals and railroads were massive undertakings that were by their very nature “lumpy.” They sucked in labor, and other resources, for the construction period and then had little further need of them. On-going labor demand was for the operation of the transport network and farming. But most immigrants did not go to the farm-frontier areas, although many did: they went to the manufacturing and service centers that prospered because of the growth brought about by expansion.

Immigrants tended to be young. This (net) flow of immigrants added to the population of the receiving countries in ages typically associated with family formation and child-bearing. It has, as we have seen, the opposite effect on the immigrant-sending or donor countries. The historical pattern of fertility in those countries receiving immigrants was, in general, higher as a result of the changed age-structure of the population, now biased toward the young. (No country which began to receive the immigrants in the 19th century had yet entered the low birth and low death rate phase of the demographic transition.) Where these immigrants located geographically in the economy also mattered. Naturally, this was determined by the demand for the skills that the laborers supplied. Even within a country, as we have seen, both fertility and mortality were sensitive to location, especially at the level of the most basic distinction of place, rural and urban.39 Thus, in an historical sense, it is not realistic to view the demographic transition separately from the flows of new (net) immigrants.

During their transitions from an agricultural to manufacturing- and service-based industry many economies achieved an extraordinary high level of investment. The high investment rates propelled the transition at a more rapid rate than otherwise possible. Since these investment rates were well beyond the capacity of domestic savings to finance, capital inflows provided the difference. A capital inflow is nothing more than an international transfer of savings and was often linked to another transfer, the transfer of human resources. When these two flows happen together in significant amounts the capital flow is said to be “population-sensitive.” The massive flow of immigrants to the expanding “new” world economies, from the “old” world economies of Europe, in the 19th and early 20th centuries also witnessed an unprecedented flow of capital (savings) in the same direction. Each flow was a response to the higher rewards expected in an economy that was expanding more rapidly than another. Yet human and capital flows are not always found together. Much, it appears, depends on size. Small marginal benefits may be sufficient to attract financial arbitrage and result in an import of capital but insufficiently large to cover the transactions costs of human migration or open the wage differential. So we frequently find that capital flows are not directly “population-sensitive.” Foreign direct investment, for instance, where capital flows are designed to overcome barriers to trade and labor flows, is another example. (Foreign direct investment is investment by firms and usually takes the form of setting up manufacturing plants and distribution facilities.) The (savings) capital flow is actually a substitute for the inhibited labor flow in this instance. In the years before the First World War, international flows of labor and capital often occur together but we should not be surprised when there are exceptions.

The international migrants carried their savings and any movables with them as property when they migrated. The balance of payments name is cash and settlers’ effects. Important as these are to the individuals, however, they contribute only a small percentage to the net capital flow. But from the migrants’ point-of-view, this was a vital flow. The success in establishing themselves on a farm, in housing or in business or a profession often depended on this endowment brought to the new land.

Quantitatively more important from a balance of payments perspective was the transfer of demand into the country whose wage rates induced the immigration. To explain this we must remember that non-tradable goods made up the greatest part of consumption. Housing, school services, medical and educational services can normally only be produced and consumed at the point of residence.40 Young immigrants (remember that youth is their principal demographic characteristic) moved their demand for housing from their home country to their new country. This further spawned a demand for social infrastructure, much of it urban. For instance, even when the western farm sector was expanding most rapidly in North America of the 19th century, the population of the urban areas in the east was expanding even more rapidly. The needed infrastructure included water and sewage systems, roads, urban lighting (both gas and electricity), railroads and urban transport systems and the like. Immigrant-receiving countries were mostly current-account deficit countries in a balance of payments sense. That is, they typically imported more than they exported. The US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Argentina, Chile, and Brazil were all countries with this immigration and balance of payments profile.41 During the Victorian era and up to World War I, they were all exporters of primary produce (grains, cotton, cattle and meat products, other farm produce, timber, minerals, and coffee). These net current account deficits were offset by capital account surpluses – think of this as an export of bits of paper, the paper representing the debt instruments such as bonds – as the overall balance of the international accounts is zero. Thus, when we look at the security placements in the world capital markets, dominated by Britain until 1914, they overwhelmingly represent the social overhead capital projects either directly or indirectly through national, provincial, state and city government debt.42

The overall timing of the capital inflows corresponds to the pace of the domestic restructuring. The faster the transition of the share composition of industry, the higher the rate of investment and the higher the reliance on imported capital (savings). Of course, there is circularity in this reasoning as one feeds on the other. What set these forces in motion were the great opportunities for rents in the “new” economies. By the same argument, it is the diminution of the economic rents that slows down the boom – the lumpiness referred to earlier. Over the course of the boom we find large immigrant flows and population-sensitive capital flows. As many historians have observed the pace of economic development (real GDP growth) in these new immigrant- receiving countries, and particularly the capital imports, has a cyclical quality. Not surprisingly, savings transferred to the expanding economies was at the expense of domestic investment in the home country. So too, was the imbedded human capital that we today call the ‘brain-drain’.43 Particularly after about 1850 when world commodity and capital markets were more integrated, the typical cycle was about 15 to 25 years in duration (the Kuznets Cycle). Kuznets Cycles were unique to the years between the early Victorian age and the outbreak of World War I.44

5.5 Unbalanced Cargoes

Prior to the 19th century, trade on the North Atlantic was carried out in relatively small ships. While there had been some growth in the size of vessels over the course of two centuries, the average 18th century Atlantic trading vessel out of Philadelphia was still less than 200 “measured” tons.45 The exports they carried from North America were largely tobacco, rice, wheat and flour, indigo, dried fish, and naval stores (specialized lumber, rope, tar and pitch, and turpentine). Ships clearing Caribbean ports in Jamaica, Grenada and Antigua tended to be a little larger as they carried goods such as raw sugar, molasses and rum. The goods shipped from Europe westward across the Atlantic were manufactured goods and specialized foodstuffs such as spices and, famously, tea. However, relative to the goods carried later, most eastbound cargoes, tended to be of high value relative to their bulk.

Yet, in the early 19th century, there was a revolution in shipping led by the demand for ships to carry low value, high bulk goods on the eastward voyage across the Atlantic. Once the political troubles between the US and Britain were resolved in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, the US became a major shipper of cotton and wheat. Somewhat earlier, British North America (Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia) became Britain’s woodyard, to use Arthur Lower’s well-worn phrase.46 Shippers responded by becoming more specialized, expanding vessel size, and increasing the number of ships. The average size of a sailing ship landing at the port of Quebec in 1800 was less than 150 registered tons. By 1851 it had risen to over 400 tons.47

The rise of the average capacity of the Atlantic fleet created a problem of unbalanced cargoes. The westbound voyage could not generate a similar volume of high value/low bulk traffic leading to what Harold Innis called the problem of unused capacity.48 He raised the questions – which he answered correctly – what price to charge on the westbound voyage for the space and what would occupy it? The solution was to carry immigrants and price the space using marginal cost principles. The increase in the supply of passenger travel space forced the price (cost to the immigrant) down. Most historians date the beginning of the age of mass trans-Atlantic migration to the immediate post-1815 years, the time when the price of westbound space declined significantly. The lowest quality passage, steerage class, was about £5 (approximately $ 24US) for the westward voyage in 1820s from Liverpool to Philadelphia. While this was about the same nominal fare being charged in 1684, in real terms (relative to the rise in average earnings) it was about one-third.49 Fares on the ships offering the poorest quality of steerage class, the timber ships, charged even less.

But passenger transport also became more practical as ships became larger and more efficient. Voyage times became shorter and more predictable, also contributing to the decline of cost per voyage. By the 1840s the new steam ships appeared. At first, the technology was applied to sailing ships as an auxiliary source of power – see Figure 5.3. Later, with the further enhancement of engine efficiency, exclusively steam-powered ships appeared. They were capable of meeting a relatively rigid time schedule and reaching more ports in Europe. For instance, in 1847 the first regular sailing by direct route to a continental European port, Bremen, was established by the SS Washington out of New York (an auxiliary). The demonstration of the latent passenger demand further spurred the development of specialized, fast ships to transport passengers and the mail. Passenger fares on the packet ships from Liverpool to Philadelphia fell to less than £3 10s by the mid-19th century, and declined further by the end of the century.50 By this time there were regular voyages of steamships devoted to passenger traffic – the precursor of the modern ocean liner. These ships were also capable of filling the hold with other goods such as wheat and cattle on the east-bound voyage.51 The unused capacity problem did not disappear in the bulk trades however, and many immigrants, but now a minority, in the late-19th century still took the trip in the old-style sailing vessels. By the beginning of the 20th century, however, sailing ships as passenger vessels had largely disappeared. The reduction of the barrier of the high fares on the trans-Atlantic passage was one of the many reasons for increased international migration.

The increase in passenger volume led in the early 19th century to the development of a European network of sea shipping routes, opened as feeders to channel passengers to the ports serving the US and Canadian migrant traffic. By mid-century, the growth of railway networks further linked places remote from the sea to the ports. The catchment area of potential migrants expanded enormously as the price of land transport fell. To a contemporary in mid- to late-19th century Europe, it must have seemed that the whole continent was on the move.

5.6 Information and Advertising

Information about costs and benefits of relocating was the key to the decision to become an immigrant or not. It had two dimensions: quantity and quality. Prior to the 19th century this information was typically modest in quantity and of uncertain provenance. It was only slowly transferred from the individuals in the host country to those in sending countries and within the latter area disseminated in an idiosyncratic manner. Furthermore, there is a ubiquity factor: the more people talked about America or Australia or South Africa the more people were open to the idea of emigration to these places. The Chinese who came to the west coast of North America in the 19th century were told stories at home of the “Land of the Golden Mountain” just as the Irish fed themselves on the myths of New York and Boston. Of course, the myth might just be that, a tall story. But it was a story that was widely spread and so came to be believed in some measure. However, for emigration to take place on a systematic basis the information had to pass a quality test of reasonableness and experience. Folk who signed on with Walter Gibson certainly had good information as far as it went. But they may not have fully comprehended the conditions under which they would serve, probably in the tobacco fields of Virginia. Part of the 19th century revolution in the technology of transport was the more rapid spread of information. Facilitated by a greater speed, variety and ease of communication (newspapers, telegraphs, the trans-Atlantic cable and international postal services) this meant a greater reliability about the information both by virtue of timeliness and source. This was particularly vital in reporting about labor market opportunities and the prospects for settlement. Information from distant locations fell in price and improved in quality and both gradually enlarged the catchment area of possible migrants. Alas it was also true that the new communications gave rise to advertising and persuasion some of which was hugely misleading. Thus, some of key elements promoting the international, and internal, mass movement of people came into being. Now, letters could be sent home regularly at low cost in which the personal fate of the past immigrants could be assessed by the potential emigrants. The high time-cost barrier was systematically reduced.

Indeed, one of the best predictors, in an historical sense, of where the immigration would come from was the stock of immigrants already in place, at least, when the flow was increasing. People informed one another, spoke of the benefits, spoke of their difficulties and even conveyed vital labor market information.52 Thanks to the exhaustive research of Simone Wegge into the social networks of German migrants in the mid-19th century, we know more about these processes and how they worked. In predicting, retrospectively, who might enter the migratory streams, family ties were very important, as were the close ties associated with the villages from which they came. Further, she found that the links were acted upon fairly soon after the first family member established themselves in the US, although some family networks operated for at least a decade. The village-family networks lasted much longer.53 The case of immigrants coming from Hesse-Cassel was not unique: “If you come to Boston, I can arrange a job on my worksite.” In addition, successful immigrants remitted cash to their homes which helped to finance (through grants or loans) the next generation of immigrants. These are known, in a balance of payments sense, as “immigrants’ remittances.” This flow of cash was accompanied by an equally vital flow of subtle information, largely immeasurable but much of it of good quality.

Information also came in the form of advertising. Some of this was blatant propaganda of self-seeking opportunists: the land development companies, the railroads with their land grants to sell off and individual employers looking for cheaper labor. But it was not necessarily a zero-sum game; the immigrant gained too. Public policy was also part of this mix as North American, Australian, New Zealand and South African provinces, states and national governments sought out and tried to attract immigrants. So too did South American countries such as Chile, Argentina and Brazil. These governments sponsored speaking tours (often bringing successful immigrants back to their places of origin), held town meetings, and published newspapers and pamphlets devoted to the cause of emigration and why their location was the most-favored.

We also cannot dismiss the effects of dramatic events as advertising. Gold discoveries such as those in California in 1840s, Australia in the 1880s and the Klondike in the 1890s, to name a few, attracted world-wide attention and induced a sudden influx of immigrants: gold rush fever. Ships set out for the west coast of North America, for instance, laden with the hopeful in 1848. But the high expectations were seldom met. The locals got there first. Even then, apart from a fortunate few, the gold rushes never did pay off for the miners/immigrants. Those who benefited were those who provided the services.54 However, the disappointed hopefuls mostly did not return home; they moved on to take up jobs in the rapidly expanding economies of the countries in which they now found themselves (although likely in an impoverished state).

5.7 Remittances: Then and Now

Immigrants’ remittances are money and goods that immigrants send to their countries of origin. For any country, this is a net flow. The payment of such remittances was common throughout the age of mass migration, but their volume increased significantly in the last third of the 19th century when the international transfer of funds became easier and immigrants became wealthier. Gary Magee and Andrew Thompson estimate that, between 1875 and 1913, US immigrants of British origin remitted approximately 16 % of their earnings back to the UK.55 The majority of remitters were motivated by four factors. First, remitters had a sense of obligation to help finance the next round of emigration (usually of other family members). Successive waves of migration were thus self-financing so long as the chain was not broken. Second, there was a desire to provide material support to those who remained at home. Indeed, the “new economics” of labor migration argues that remittances were part of an implicit contract between immigrants and the families they left behind – it was the expected thing to do.56 The decision to migrate was inseparable from the remittance decision for many. For instance, the many ethnic Chinese laborers who went to 19th century North America (and elsewhere) through revolving labor contracts sent a high proportion of their (low) wages home simply to afford a higher standard-of-living for parents, spouses and children in China.57 Many, particularly the Southern European immigrants to North America, came with no such guarantee of employment but were similarly motivated.58 However, there was also a third motivating factor: investing activities, acquiring and maintaining a home in their native country for planned retirement. Last, we must note that as several recent natural disasters reveal, émigrés contribute generously to (welfare) relief efforts in their country of origin.

Today, the World Bank’s reports of remittance flows throughout the world indicate that they have been growing rapidly. As measured in US dollars, migrant remittance inflows increased from $ 2 billion in 1970 to $ 35 billion in 1985 and to $ 132 billion in 2000. The estimate for 2008 is $ 433 billion, and it has been argued that the true amount could be as much as 75 % higher.59 Clearly much of this increase is due to greater diligence in tracking the flow; individual countries are doing a better job of collecting data and more countries are reporting to the World Bank. Because these flows were (and are) much larger than had been recognized previously, the question is raised as to what extent these remittances contribute to economic development in the receiving country? How are the families and friends that receive the monies using this income flow? For one group, the return migrants, the answer is clear: saving in the form of assets – see the next section of this chapter. One answer to this question, however, is clear in the case of Nepal and Malawi: the funds used contribute to the education of the young who receive more schooling than otherwise would be the case.60 Other questions are the subject of debate by development researchers who typically examine the problems of a particular country. But, at this juncture, there are few general lessons to be drawn.

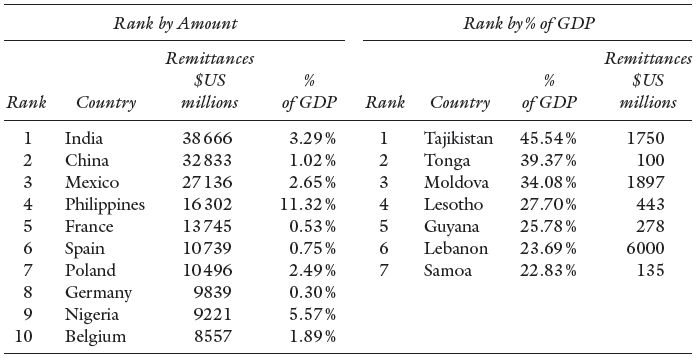

The ten top countries in the World Bank database for 2007 with respect to absolute amount of migrant remittance inflows measured in millions of US dollars are given in Table 5.3.

There are few surprises here; these are generally large countries with a large number of their native-born living elsewhere, but the right hand column has been included to indicate that, with the exception of the Philippines, these large dollar amounts are in reality a small percentage of the country’s GDP. Perhaps a more informative way of looking at the World Bank data is to look at the top ten countries with respect to percentage of the country’s GDP. With the exception of Lebanon, these are all classified as either “low-income” or “lower middle-income” countries. Remittances make a significant contribution to the immigrant-sending countries. While we lack the data to examine this as carefully as might be desired, it seems likely that the motivation and uses of these remittances has not changed much over the centuries. What has changed is the ease with which monies can be moved internationally, and the increase in volume has made this an important element for future study.

Table 5.3 Remittances by Absolute Amount and Rank by Percentage of GDP, 2007.

Source: United Nations (2008) Migration and Remittances Factbook 2008, http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/2009Migration_Chart/ittmig_wallchart09_table.xls.

5.8 There and Back Again – Reverse Migrations

We do not know with any certainty where emigrants go (see earlier – Who’s In and Who’s Out).61 Even today it requires a highly focused investigation and plenty of research dollars, and time, to discover the truth of the matter.62 But there are some vital clues and some historical results. In the late 20th century in the United States approximately 30 % of all the foreign-born residents (citizens and legal permanent residents) enter the emigration stream. This has been surprisingly constant for the entire century.63 According to the last full census about one-quarter of a million permanent US residents left the US each year in the decade of the 1990s to take up permanent residence elsewhere. Over 80 % of these emigrants were foreign-born.64 We do not know that they all are true return migrants (returning to their country of origin) but many, probably a majority, are. Similarly, in the United Kingdom in 2006 and 2007, the emigration flow (about 63 % of the immigrant flow) was made up of a slight majority of non-British citizens (51 %) and of the remainder who are British citizens many of which would be foreign-born. (The British do not collect the same data as the US). The institutionalized free movement of labor within the European Union gives a range of flexibility to British migrants and a higher ratio of emigrants to immigrants than the US, an option not available to non-Europeans and, of course, not available to US emigrants. Germany too, whose data more resembles that collected in the US, finds that foreign-born residents are approximately 10 % of the total population, and about 80 % of the outflow, similar to the US.65

Return migration: immigrants to a country who have full-time residence status and who return to their country of origin (for a period of at least one year). They may have host country citizenship. Historically, before the 1920s, countries were more relaxed about citizenship and many immigrants never acquired the citizenship of their new country.

Temporary migrants: immigrants who have limited rights of residence such as “guest workers,” workers on specific term contracts and harvest time agricultural labor. Historically, many individuals did have a right to stay in the host country but chose not to do so either because of their contracts provided passage home or there was active discrimination directed at them. Chinese workers often fell into this group. The Chinese refer to temporary migrants as “swallows.”

Visitors: Some temporary migrants are technically “visitors.” Many such visitors come from northern countries taking up winter residence in warmer climates, such as Spain and Florida; they are often referred to as “snowbirds.”

But we know a little bit more of the recent German return emigration than we do of most others. Return migration was closely associated with remittances, as noted earlier. A close association with the family at home and individual life-cycle planning seem to lie behind this link between return and remittances. The latter suggests that individuals planned to return home although not necessarily at the beginning of their immigration experience. The more highly educated are more prone to return migration than those with low levels of human capital provided the labor markets in the country of origin are relatively open. Those whose actual income was well below that that was reasonably expected, whatever their level of education, were more likely to go home.66 Women tended to carry more of their “being a migrant” advantage home to their labor markets of origin than men.67 The causes of return migration were likely the same in the past as they are today. To be sure, the institutional setting was different, such as the lack of open labor markets in the country of origin, and the costs and penalties higher than they are now. This was a barrier to return.

Nevertheless, immigrants did return home. Even in the 17th century folk were returning to England from the New England colonies. The number can never be known as most left quietly with no records of their movements kept. Of those who left records, the highly educated, puritan zeal to proselytize at home seems to have motivated some to return. Many returned for more prosaic reasons, such as not adapting to the new world and escaping debt.68 And, as mentioned earlier, an unknown but large number of convicts and prisoners returned to Britain. The return of the British immigrants continued and probably reached its height, in both absolute and proportional terms, in the 50 years before the First World War. But the British were not alone.

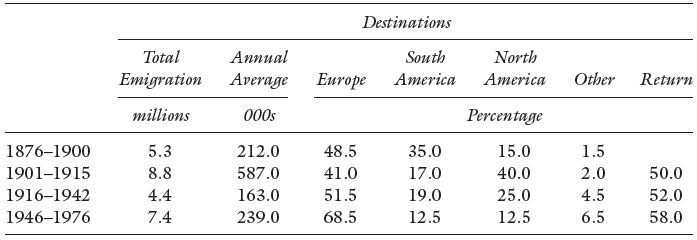

Table 5.4 Italian Emigration by Destination, for Periods, 1876–1976.

Source: data from Bailey (1999) 24.

The years of high Italian immigration to the Americas are highlighted in Table 5.4. In the years 1870–1929, more than 50 % of the immigrants returned home. Italy had one of the highest rates of return migration and unlike the British return was much more dominated by acquisition of home country assets and the life-cycle retirement motives. (Southern Europeans, in general, appear more drawn back to their countries of origin than most.) The author Dino Cinel argues that the remittances associated with the return migration, actual and anticipated, were “one of the most important dynamics in the Italian economy and society during the half-century 1875–1925.”69 It touched so many families and reached a volume that inspired a national debate about how the imported savings could be directed in a macroeconomic sense.

No immigrant group had a higher rate of return migration than the Japanese who entered the US before the Second World War – a staggering 85 % of the 288 thousand immigrants who had arrived since the inception of Japanese immigration in the third quarter of the 19th century. Japanese immigrants, like their Chinese and other East Asian counterparts, had come under increasing anti-oriental prejudice with its origins in the late-19th century. By the period 1913–1925 this reached fever pitch with many states, especially in the west, restricting the ownership of agricultural land by Japanese immigrants.70 Not surprisingly, faced with this xenophobic attitude, the Japanese immigrants and many of their American-born children (Nisei) chose to leave. The exodus drew disproportionately from those connected to agriculture (market gardening) including the large number of farm laborers who made up the ethnic Japanese population of the US. The end result was that the Japanese population who were left in the US was comprised of the successful professionals and therefore was (or looked) essentially “middle class” – which itself has engendered a debate about the success of the Japanese in America.71 There is little question that the majority of Japanese immigrants intended to reside permanently in the US. Circumstances did not permit them to do so.

5.9 Diaspora

The term “diaspora” was first used to describe the removal of the Jews from their biblical homeland during the Babylonian Captivity and their subsequent spread and, often forced, movement throughout the world. In recent years the word has come to be applied to many other distinct ethnic or culturally-defined populations who shared some general characteristics of spread and forced movement. Thus in addition to the Jewish diaspora, we may talk of the African diaspora with its origins in Arab/European/American slavery and include the migrations and settlement of, say Afro-Caribbeans in Britain during the 20th century. Diasporas transcend national boundaries. And, diasporas may be found in the following list (with their initial cause):

- the Acadians, military-political resettlement in the 18th century;

- the Armenians, political repression in the 19th and 20th century;

- the Eritreans, political repression and poverty late-20th and early-21stt centuries;

- the Chinese, forced labor contracts and poverty in the late-19th and early-20th centuries;

- the European gypsies, ethnic discrimination in the 19th and 20th centuries;

- the Highland Scots, agricultural displacement in the 18th and 19th centuries;

- the Indians, forced labor contracts in the 19th and 20th centuries;

- the Irish, recurring famine conditions and poverty in the 19th and early-20th centuries;

- and many others.

What unites the various elements of the list is that there is an event such as a famine or political repression or religious or cultural intolerance that sets the forces of diaspora in motion.

A. The Chinese