Southeast of Muscat stretches Sharqiya (“The East”), a generous swathe of sea, sand and mountain, spread across the southeasternmost tip of the Arabian Peninsula. Officially divided into two governorates of roughly equal size, North and South, it’s perhaps the most diverse part of the country, offering a beguiling snapshot of Oman in miniature, from the sand-fringed coastline, through the rugged Eastern Hajar mountains to the rolling dunes of the Sharqiya Sands. Culturally, too, the region retains a distinct appeal. It’s Oman at its most traditional, with a long and proud history of tribal independence – and occasional insurrection against the authority of the sultan in Muscat. The interior of Sharqiya is also one of the few places in Oman where you’ll still see evidence of the country’s traditional Bedu lifestyle, with temporary encampments dotted amid the rolling sands – although the camels of yesteryear have all but been replaced by Toyota pick-up trucks and 4WDs.

In practical terms, Sharqiya divides into three main parts. The first is the coast, with a string of attractions including the historic towns of Quriyat, Qalhat and Sur, and the turtle beach at Ras al Jinz. Running parallel to the coast, the craggy heights of the Eastern Hajar mountains (Al Hajar Ash Sharqi) provide numerous spectacular hiking and off-road-driving possibilities, including the celebrated ravines of Wadi Shab and Wadi Tiwi. On the far side of the Eastern Hajar, the Sharqiya interior boasts a further swathe of rewarding destinations, including the magnificent dunes of the Sharqiya Sands, the slot canyons of Wadi Bani Khalid and a string of interesting towns, notably the personable market centre of Ibra and the staunchly traditional Jalan Bani Bu Ali.

It’s possible to make a satisfying loop through Sharqiya by heading down the coastal highway to Sur and Ras al Jinz, and then returning along the inland route via Ibra – or vice versa – passing the bulk of the region’s major attractions en route.

Brief history

Something of a backwater nowadays, Sharqiya’s rather sleepy present-day atmosphere belies its illustrious past, when its boat-builders, merchants and mariners made the region one of the most commercially vibrant and cosmopolitan in the country. Sharqiya’s prosperity was founded on the sea, with a string of bustling ports and entrepots, most notably Qalhat, whose fame attracted visits by both Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo, as well as Quriyat up the coast. The pivotal moment in Sharqiya’s history was the arrival in 1508 of the Portuguese, who sacked both Qalhat and Quriyat – an event from which neither town ever completely recovered. The demise of Qalhat, however, spurred the growth of nearby Sur, which subsequently became the capital of South Sharqiya, growing wealthy thanks to its dhow-building yards and lucrative trade in arms and slaves. Inland, Ibra – now the capital of North Sharqiya – also became rich for a time thanks to passing trade. Increasing British restrictions on slaving and arms smuggling during the nineteenth century led to a gradual eclipse in the region’s fortunes, however, and during the early twentieth century Sharqiya became a major crucible of rebellion against the sultan in Muscat, usually spearheaded by leaders of the powerful Al Harthy tribe, based in Ibra.

Shutterstock

DESCENDING FROM THE SALMA PLATEAU

Highlights

Wadi Shab and Wadi Tiwi Two of Oman’s most picture-perfect wadis, with palm-fringed ravines running between sheer sandstone cliffs down to the sea.

Wadi Shab and Wadi Tiwi Two of Oman’s most picture-perfect wadis, with palm-fringed ravines running between sheer sandstone cliffs down to the sea.

Jaylah and the Salma Plateau Superb off-road drive across the top of the Eastern Hajar mountains, passing the spectacularly located Bronze Age tombs and towers of Jaylah en route.

Jaylah and the Salma Plateau Superb off-road drive across the top of the Eastern Hajar mountains, passing the spectacularly located Bronze Age tombs and towers of Jaylah en route.

Sur Southern Oman’s most appealing town, with a pretty harbour fringed with watchtowers and the country’s only surviving dhow-building yard.

Sur Southern Oman’s most appealing town, with a pretty harbour fringed with watchtowers and the country’s only surviving dhow-building yard.

Ras al Jinz Arabia’s premier turtle-watching destination.

Ras al Jinz Arabia’s premier turtle-watching destination.

Ibra One of the region’s liveliest and most personable towns, with a colourful souk and a pair of fine old traditional mudbrick villages.

Ibra One of the region’s liveliest and most personable towns, with a colourful souk and a pair of fine old traditional mudbrick villages.

Sharqiya Sands Iconic desert landscape, with towering dunes, roving camels and superb sunsets.

Sharqiya Sands Iconic desert landscape, with towering dunes, roving camels and superb sunsets.

Masirah island Extreme remoteness is only half the charm of this desert island of windswept beaches off Sharqiya’s far southern coast.

Masirah island Extreme remoteness is only half the charm of this desert island of windswept beaches off Sharqiya’s far southern coast.

HIGHLIGHTS ARE MARKED ON THE MAP

As with many of the country’s other leading ports, Sur’s fortunes have been revived since the accession of Sultan Qaboos by the construction of a massive new industrial complex, while the opening of the new dual-carriageway coastal highway in 2008 has further reinvigorated the region’s economy – albeit at the cost of some of the area’s former sleepy, slow-motion charm. Though lagging a few years behind, the interior appears on a similar track, provided a recent boost in the advent of yet another dual-carriageway – the newly-dubbed Sharqiya Expressway, expected to link Ibra to Sur by the end of 2018.

The Muscat–Sur coastal road

The most popular route into Sharqiya follows the smooth Sharqiya coastal highway from Ruwi in Muscat south to Quriyat and Sur, with the Arabian Gulf on one side and the rugged summits of the Eastern Hajar on the other. Although it’s taken a toll on the various natural attractions en route, the highway has provided an undeniable boon to regional development and brought many of the area’s attractions within easy reach. These comprise an interesting blend of the historical and the natural, including the old fort of Quriyat, the ruined city of Qalhat, the scenic dam at Wadi Dayqah, the off-road drive over the Eastern Hajar to Ibra – via the Bronze Age tombs of Jaylah – and, last but certainly not least, two of Oman’s most spectacular wadis: Wadi Shab and Wadi Tiwi.

Quriyat

The first town of any significance south of Muscat, QURIYAT lies some 80km from the capital, a 45-minute drive from Ruwi along a fast and relatively empty new stretch of dual carriageway which weaves between the craggy foothills of the Eastern Hajar. Situated about 7km north of the highway as it swings west to the coast and onwards to Sur, the modest town is huddled around a low-key souk and an old fort, about half a kilometre from the seafront.

Quriyat had the dubious honour of being one of the first towns in Oman to experience the destructive attentions of the Portuguese fleet under Afonso de Albuquerque. Albuquerque’s soldiers attacked the town in August 1508, setting it ablaze and massacring its inhabitants – captives, it is said, had their noses and ears cut off, a popular Portuguese way of discouraging further resistance to their rapacious rule.

Quriyat Fort

Mon–Thurs & Sun 8.30am–2.30pm • Free

Quriyat’s principal attraction is its two-hundred-year-old fort, which sits right in the middle of town, just beyond the souk on your left as you drive in. Following several years of much-needed renovations, it was re-opened to the public in 2013, allowing you to climb to its rooftop for views across to the harbour. It’s not the most memorable of forts, though it’s worth checking out the fine old wooden door at the entrance, flanked by a pair of rusty cannon. Shuttered ground-floor windows ring the building on three sides, suggesting that domesticity, rather than defence, was formerly the principal concern.

The seafront

Continue along the road past the fort and a large mangrove swamp to reach the town’s pretty seafront corniche, at the end of which is the harbour, with boats drawn up on surrounding sands overlooked by a round watchtower sitting proudly just off the headland above.

Wadi Dayqah

Signed 19km off the coastal highway to the south of Quriyat • Daily 8am–10pm • Free

After winding through the rugged, arid mountainscape that encompassed the road from Quriyat, the first glimpse of this vast, shimmering expanse of turquoise water is quite the welcome sight. The reservoir measures some eight kilometres from end to end, supported by Oman’s largest dam – built with the intent of providing 100 million cubic metres of water to the growing populations of Quriyat and Muscat. There’s plenty of parking and a simple café-cum-restaurant beside the large, manicured park that overlooks the water, making a pleasant picnic spot from which to admire the panoramic views and people-watch when the weekend crowds arrive.

The Bimmah Sinkhole

Daily 7.30am–10pm • The exit to the park is signed off the coastal highway 38km south of the Quriyat turn-off (5km south of Dhabab turn-off and 8km north of the Bimmah turn-off); follow the road under the highway and down to the sea, then turn left at the T-junction (signed towards Dhabab and Hawiyat Najm Park) and continue for 1.5km, then left again at the sign to the park

The Bimmah Sinkhole is now enclosed within (and signed as) the Hawiyat Najm Park. Sadly, the sinkhole itself – formerly one of the coast’s most magical beauty spots – has now been utterly defaced in the name of tourism, with an ugly stone wall erected around its rim and concrete steps with bright blue handrails running down inside, which has succeeded in reducing the whole place to the level of suburban naff. If you can ignore all this, the interior of the sinkhole is still rather lovely, with a miniature lake at the bottom, its marvellously clear blue waters populated with shoals of tiny tadpole-like fish, and reflections from the water playing on the layered limestone above.

Fins

South from the Bimmah Sinkhole, it’s possible to drive along the old coastal road (tarmacked hereabouts) which runs close to the sea through Bimmah village and on to the village of FINS, 18km further on, where the tarmac ends – a pleasant change of pace and scenery from the coastal highway. There’s a turn-off back to the highway a couple kilometres past Bimmah (10km along the road), and another one at Fins. Fins itself is flanked by an attractive string of white-sand beaches including the popular “White Beach”, 5km south of the village, although the whole place attracts a steady stream of visitors, particularly at weekends.

Wadi Shab

The closest access road to the wadi lies about 600m to the north, with exits off the highway serving both directions; alternatively, approaching from Wadi Tiwi you can continue 3km north along the coast road • Boats to the trailhead run from the car park every few minutes 7.30am–5pm daily • 1 OR return boat fare

South of the Bimmah Sinkhole lie the dramatic Wadi Shab and Wadi Tiwi, a pair of spectacularly narrow mountain ravines, hemmed in by vertiginous sandstone walls with a verdant ribbon of date plantations and banana palms threading the base of the cliffs. Driving south, Wadi Shab is the first of the two you’ll encounter, and perhaps the most rewarding. There’s no road into the wadi (unlike Wadi Tiwi) – which is a significant part of its charm – though there’s plenty of parking beneath the concrete flyover carrying the coastal highway. Here you’ll find toilets, a simple café and boats that ferry hikers to the trailhead just opposite the pond. Note that no camping or cooking is allowed in the wadi.

After the first kilometre or so of the hike, the gorge narrows and a small footpath runs along a rock ledge just above the wadi floor, choked with huge boulders. Another kilometre or so up the valley, past further plantations and the faint ruins of old villages, the valley bends back to the left, where you’ll soon reach some inviting rock pools that make a refreshing spot for a swim. About a couple of hundred metres along the water is a narrow passage beneath the rock (when water levels are high you’ll have to hold your breath for a few metres to pass through) that opens up to a dreamy little cavern. Doubling back to where the pools begin, you can follow the rough trail along the right side of the canyon to reach deeper into the wadi, though be sure to arrive back at the trailhead in time for the last boat back to the car park. Understandably, the wadi’s popularity with local and foreign tourists means that you’re highly unlikely to have the place to yourself.

Well-signed off the coastal highway about 1km south of Tiwi (with exits serving both directions); the road wraps around to pass beneath the flyover, and is just about doable in a 2WD, assuming it hasn’t been raining

A couple of kilometres south of Wadi Shab lies the almost identical Wadi Tiwi, another deep and narrow gorge carved out of the mountains, running between towering cliffs right down to the sea. It’s less unspoiled than Wadi Shab, thanks to the presence of a road through the ravine (although, as at Wadi Shab, the dramatic scenery at the entrance has been marred by the construction of a large flyover), although it compensates with its old traditional villages, surrounded by lush plantations of date, banana and mango, and criss-crossed with a network of gurgling aflaj.

The paved road into the wadi starts off by tracing the valley floor for about 3km until reaching the first village of note. Here, the track narrows dramatically, squeezing its way between old houses and high stone walls. The road continues to wind along another 7km between plantations and past the rock pools which collect between the huge boulders below, becoming increasingly rough and steep – though mostly paved – before finally coming to an end at the village of Mibam. It’s a spectacular, if nerve-jangling, drive. From here, it’s a ten-minute scramble down to the wadi along a steep path through the date farms to reach a waterfall and a stunning set of pools. Mibam is also the launching point for the popular two-day hike over the mountains to reach Wadi Bani Khalid.

Jaylah and around

At the turn-off for Fins, brown signs point inland to the ancient tombs of Jaylah (or Gaylah) and the village of Qurun. This is one of the most memorable drives in Sharqiya, a spectacular off-road traverse of the barren uplands at the top of the Eastern Hajar with a cluster of wonderfully atmospheric Bronze Age beehive tombs en route. The track also offers a convenient short cut from the coast to Ibra, although it’s probably no quicker than taking the main road through Sur. The route comprises about 50km of generally good graded track, but there are some pretty rough, and sometimes extremely steep, sections here and there – 4WD is essential, as are strong nerves if you’re driving yourself.

Salma Plateau and Qurun

The route begins by switchbacking vertiginously up the flanks of the Eastern Hajar, a breathless thirty-minute drive with increasingly spectacular views down to the coast below. At the top, you reach the sere Salma Plateau at the summit of the Eastern Hajar: a rolling expanse of gravel plain, dotted with only the sparsest of vegetation. There’s virtually no sign of human habitation until you reach tiny Qurun, one of the loneliest villages in Oman – little more than a haphazard cluster of houses tucked away in the lee of cliff, and feeling an awfully long way from anywhere.

The tombs and towers

Past Qurun, keep left, navigating a boulder-strewn section of wadi bed for a few hundred metres, after which the track resumes, becoming increasingly rough. About 7km west of Qurun you reach an unsigned T-junction. Turn right here for Ibra, or left to reach the first of a marvellous collection of Bronze Age tombs and towers which dot the surrounding uplands.

The most notable structure here is a single large tower, restored to a height of around 10m (you’ll already have seen it up above on your left as you approach the T-junction), while the remains of six beehive tombs, which have survived in varying stages of completion, sit in a line along the very edge of the precipitous ridge beyond. The tombs are perfect examples of their type, crafted from finely cut stones, each with a small opening at the base, although it’s the marvellously wild and remote location which really captures the imagination – a perfect example of the ancient Omani predilection for constructing funerary monuments in the highest, wildest and most remote places.

Hidden away in the depths of the Eastern Hajar around 8km north of Qurun village lies the celebrated Majlis al Jinn (“Meeting place of the Jinn”), one of Oman’s most spectacular and challenging destinations for adventurous speleologists. The Majlis is one of the world’s largest cave-chambers, some 120m high – larger than the great pyramid of Cheops. Entrance to the cave is via three vertical sinkholes, involving a free descent of between 118m and 158m and including the sinkhole popularly known as “Cheryl’s Drop”, after the daring lady who first tackled the descent. Unfortunately, the cave has been closed since 2008, when the government, inspired by the success of Al Hoota Cave, announced plans to develop the cave as a major tourist attraction. A likely reopening date has yet to be announced.

Turning right at the T-junction and continuing towards Ibra you’ll see more tombs scattered about the mountainside to the right of the road. After another 3km you reach a second cluster of monuments spread out on either side of the road, including ten or so beehive tombs and a trio of well-preserved towers – perhaps even finer than the first group, although the location is less spectacular.

Wadi Nam

A series of isolated and ramshackle villages dot the bewildering network of tracks which crisscross the plateau, tucked away in hollows among the mountains. A few kilometres beyond the second group of tombs you reach another unsigned T-junction. Turn right here for Ibra, descending steeply down a poorly maintained track to Wadi Nam, a dramatic little valley hemmed in by sheer black-earth walls. From here, it’s a straightforward, if bumpy, ride down the wadi to the village of Al Shariq, where the tarmac resumes and leads to Ibra, some 50km further on.

Qalhat

The ancient city of QALHAT was, up until the sixteenth century, one of the most important on the Omani coast – “A sort of medieval Dubai” as travel writer Tim Mackintosh-Smith described it in his Travels with a Tangerine. Qalhat’s importance derived from its status as the second city of the Kingdom of Hormuz, serving as a major commercial hub in the Indian Ocean trade routes. The fame of the city attracted visitors including both Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta. Despite its prosperity, the city suffered from certain strategic weaknesses. A falaj system provided a reliable source of water, but there was almost no agricultural land available and all food had to be imported by land or sea. Qalhat’s already tenuous foothold on the Omani coast was further undermined by a serious earthquake at the end of the fourteenth century, while just over a hundred years later, in 1508, the newly arrived Portuguese delivered the coup de grace, sacking the city, massacring its inhabitants and setting its buildings and large fleet of boats on fire, an event from which Qalhat never recovered.

The ruins

The site was officially closed at the time of writing, although there’s nothing to stop you walking up for a look

The ruins of the city, originally triangular in plan, cover an area of over sixty acres, although it’s difficult to make much sense of the confusing wreckage of assorted walls and towers scattered over a rocky headland and along the adjacent wadi. The only notable surviving structure is the Mausoleum of Bibi Maryam, a quaint little cuboid building enshrining the remains of the saintly Bibi Maryam who, according to Ibn Battuta, had ruled the city until a few years before his visit in 1330. The colourful tiles which covered the walls right up until the nineteenth century have now vanished, and the dome has also collapsed, though the remains of the delicately moulded arches and doorways have somehow survived the years.

ARRIVAL AND DEPARTURE QALHAT

By car Exit the coastal highway at the brown sign for “Ancient City of Qalhat” and then continue west until you reach the coast road; from here, head south (right) for around 2km, wrapping around to face the highway, about 300m before which you’ll see a brown sign for “Madinat Qalhat”, pointing across the wadi bed to the east: follow this dirt track (passable in a 2WD) as it passes through small palm grove, past which you’ll see ruins up on a hillock to your left. Park along here and walk up to the mausoleum.

Far and away the most appealing town in Sharqiya, SUR enjoys one of the eastern coast’s prettiest locations, with the old part of town sitting on what is almost a miniature island, surrounded by a tranquil lagoon and offering views of mingled water and land in every direction. Sur is also one of the most historic settlements in the south, formerly a bustling port and trading centre whose maritime traditions live on in the intriguing dhow-building yard, the only surviving one of its kind in Oman. Further reminders of Sur’s illustrious past are provided by the trio of forts and string of watchtowers that encircle the town and harbour.

Sur’s attractions are quite spread out. The small but lively town centre and souk – a colourful tangle of brightly illuminated shops and cafés – lies at the western end of the island, from where the breezy seafront corniche runs down the coast for 1km or so to reach the old harbour, home to Sur’s dhow-building yard and a trio of watchtowers, beyond which lies the pretty village of Ayjah.

Brief history

The easternmost major settlement in Oman, Sur has always looked to the sea. Following the demise of Qalhat in 1508, the town developed as the region’s most important port, shipping goods to and from India and East Africa, and also established itself as the country’s most important ship-building centre, vestiges of which remain. A succession of reverses during the nineteenth century eroded the town’s fortunes, including the arrival of European steam-ships in the Indian Ocean, the British prohibition of slavery, the split with Zanzibar and the rise of the port of Muscat. Recent years have seen a modest revival in the town’s fortunes thanks to the opening of the massive OLNG natural gas plant just up the coast.

The harbour

The prettiest part of town – and the obvious place to start a visit – is around the harbour at the southern end of the seafront corniche opposite the contiguous village of Ayjah. Three watchtowers on successively higher rock outcrops sit above the harbour, overlooking the suspension bridge connecting Sur and Ayjah and the restored lighthouse nearby, backed by an attractive sprawl of low white houses – one of southern Oman’s prettiest views.

The dhow-building yard

Just past the suspension bridge is Sur’s dhow-building yard, all that remains of the town’s once flourishing boat-building trade and the only surviving dhow yard in Oman. There are usually a couple of boats under construction here, while the carcasses of further old dhows can be seen further along the beach, awaiting restoration or recycling. Visitors are welcome to look around and watch the (now exclusively Indian) workforce chiselling, hammering, sawing and planing.

Fatah al Khair

Continuing south past the dhow yard, the road runs along the edge of the lagoon to where the old Fatah al Khair (“The Triumph of Good,” roughly translated), an elegant ocean-going ghanjah, stands propped up next to the road on the waterfront as a monument to the city’s maritime heritage. In 1993, when it was discovered to be the last-surviving vessel of its kind, the local government bought the vessel from its erstwhile Yemeni owner, bringing it to rest not far from the spot where its keel was laid in 1951. Plans to open a maritime museum in the adjacent building have yet to bear fruit.

Ayjah

Across the suspension bridge just east of Sur is the neat little village of AYJAH (also spelled Aygah), spread out along the headland bounding the western side of the harbour. Driving into the village, follow the brown sign pointing left towards the neat little Al Ayjah Fort (also known as Al Hamooda Fort; Mon–Thurs & Sun 8.30am–2.30pm; 500bz) – itself of little interest – and continue until you reach the picturesque waterfront. The village is one of the prettiest in Sharqiya: a low-lying huddle of simple old whitewashed waterside houses interspersed with more chintzy modern villas – many sport porticoes supported by the village’s unique style of pillars topped with goblet-shaped capitals. It’s worth tracing all the way around the harbour to the modern lighthouse, with fine sea views, plus a surprising number of goats.

Oman was formerly famous for the excellence of its boats and the skills of its sailors, whose maritime expertise – backed up by a detailed understanding of the workings of the local monsoon (a word derived from the Arabic mawsim, meaning “season”) – laid the basis for the country’s far-reaching commercial network, and for its string of colonies in East Africa. Boats were formerly built at centres all along the coast, though only the one at Sur now survives – offering a fascinating glimpse into an almost vanished artisanal tradition.

The word dhow is generally used to describe all traditional wooden-hulled Arabian boats, although locals distinguish between a wide range of vessels of different sizes and styles. The traditional Arabian dhow – such as the large, ocean-going boom – was curved at both ends, while other types – such as the sambuq and ghanjah – boasted a high, square stern, apparently inspired by the design of Portuguese galleons. Traditional dhows were driven by enormous triangular lateen sails (a design which allowed them to sail much closer to the wind than European vessels), although these have now been replaced by conventional engines. Another peculiarity of the traditional dhow was its so-called stitched construction – planks, usually of teak, were literally sewn together using coconut rope, although nails were increasingly used after European ships began to visit the region.

For a fascinating insight into traditional Omani boat-building, seafaring and navigation, read Tim Severin’s entertaining The Sindbad Voyage; Severin’s specially commissioned dhow – the Sohar – was built in Sur and now sits in the middle of a roundabout in Muscat.

As Sineslah Castle

3km west of town centre • Mon–Thurs, Sat & Sun 7.30am–6pm, Fri 8–11am • 500bz

The more worthwhile of Sur’s restored forts lie towards the western side of town. As Sineslah Castle (also spelled Sunaysilah) sits in a commanding position on a hill just to the right (north) of the main road out of town – drive right up through the compound the gates to reach the car park. There’s not much inside apart from a neat little mosque, a Qur’an school and a surprisingly civilized prison – unusually for an Omani dungeon, it even has windows. Steps climb up to the eastern and western towers, from where a walkway stretches around the parapet offering fine views over the white sprawl of Sur below, spiked with dozens of minarets and the occasional watchtower.

Bilad Sur Fort

6km west of town centre • Mon–Thurs & Sun 8.30am–2.30pm • 500bz

The over-restored Bilad Sur Fort stands 3km further down the road from As Sineslah Castle. It’s almost twice the size, though much of it is taken up by the broad gravel courtyard. The most notable feature is the pair of unusually shaped, two-tier towers rising from the eastern walls.

ARRIVAL AND GETTING AROUND SUR

By car Sur is about a 2hr drive from Muscat along Highway 17, and about the same from Ibra along Highway 23.

By bus/microbus Buses and microbuses depart from the bus station in the centre of the souk. Mwasalat (![]() 25540019,

25540019, ![]() mwasalat.om) runs three daily buses to Azaiba in Muscat (3hr 50min–4hr 50min; departing 6am, 6.45am and 2.30pm) and two to Ibra (2hr 10min; departing 6am and 2.30pm).

mwasalat.om) runs three daily buses to Azaiba in Muscat (3hr 50min–4hr 50min; departing 6am, 6.45am and 2.30pm) and two to Ibra (2hr 10min; departing 6am and 2.30pm).

By taxi A taxi to almost anywhere in Sur should cost no more than 300bz.

Sur Beach Holiday Resort 3km northwest of the town centre on the road to Qalhat ![]() 2554 2031,

2554 2031, ![]() surbhtl@omantel.om; map. This old-fashioned three-star resort looks like it’s stuck in the 1970s, but compensates with a reasonable spread of facilities and a helpful and welcoming atmosphere. Accommodation is in a mix of cosy, old-fashioned rooms (some with sea views and balconies) or in two-storey villas (sleeping two), with living room and small kitchen, plus more modern and stylish furnishings. There’s a stretch of slightly stony beach and a rather drab little pool, while facilities include an in-house international restaurant (7 OR for the dinner buffet), sports pub, Arabian live-music bar, gym and tennis court. Doubles 55 OR, villas 85 OR

surbhtl@omantel.om; map. This old-fashioned three-star resort looks like it’s stuck in the 1970s, but compensates with a reasonable spread of facilities and a helpful and welcoming atmosphere. Accommodation is in a mix of cosy, old-fashioned rooms (some with sea views and balconies) or in two-storey villas (sleeping two), with living room and small kitchen, plus more modern and stylish furnishings. There’s a stretch of slightly stony beach and a rather drab little pool, while facilities include an in-house international restaurant (7 OR for the dinner buffet), sports pub, Arabian live-music bar, gym and tennis court. Doubles 55 OR, villas 85 OR

Sur Grand Hotel About 4.5km northwest of the town centre on the road to Qalhat ![]() 2524 0000,

2524 0000, ![]() surgrandhotel.com; map. Standing in isolation about a kilometre beyond the town’s western edge, though just a few hundred metres from the beach, this airy new hotel offers wonderful views over the sea and towards the mountains from its well-appointed, modern rooms with balconies. There’s also a wellness centre offering complimentary morning yoga and a good international restaurant downstairs (dinner buffet 7 OR), though perhaps the star attraction is the pleasant rooftop pool and terrace. 35 OR

surgrandhotel.com; map. Standing in isolation about a kilometre beyond the town’s western edge, though just a few hundred metres from the beach, this airy new hotel offers wonderful views over the sea and towards the mountains from its well-appointed, modern rooms with balconies. There’s also a wellness centre offering complimentary morning yoga and a good international restaurant downstairs (dinner buffet 7 OR), though perhaps the star attraction is the pleasant rooftop pool and terrace. 35 OR

Sur Hotel ![]() 2554 0090,

2554 0090, ![]() surhotel.net; map. In a convenient location right in the middle of the souk – although inevitably not the quietest place in town – with simple but perfectly clean and comfortable rooms, helpful, knowledgeable staff and reasonable value at the price. 12 OR

surhotel.net; map. In a convenient location right in the middle of the souk – although inevitably not the quietest place in town – with simple but perfectly clean and comfortable rooms, helpful, knowledgeable staff and reasonable value at the price. 12 OR

Sur Plaza Hotel Around 4km inland from the centre ![]() 2554 3777,

2554 3777, ![]() omanhotels.com/surplaza; map p179. The town’s most upmarket option, with pleasant public areas arranged around a central atrium, although rooms themselves are looking a little drab and tired. Facilities include Oysters Restaurant. There’s also a medium-sized pool with basic sun terrace and loungers, plus gym, business centre and a car rental office. 47 OR

omanhotels.com/surplaza; map p179. The town’s most upmarket option, with pleasant public areas arranged around a central atrium, although rooms themselves are looking a little drab and tired. Facilities include Oysters Restaurant. There’s also a medium-sized pool with basic sun terrace and loungers, plus gym, business centre and a car rental office. 47 OR

Zaki Hotel Apartments 1km west of the centre ![]() 2554 5924,

2554 5924, ![]() zakihotelapartment.com; map p179. Spotless new hotel apartments recently opened by the same friendly and enterprising family that runs the restaurant of the same name next door. Each comes with a kitchen, and the most spacious apartments sleep four (45 OR). A breakfast buffet is served in the upstairs restaurant, while downstairs beside the reception is Sur’s brightest little cafe (open 24hr). Unfortunately for light sleepers, there’s a large mosque just across the street – best to avoid the apartments facing north. 35 OR

zakihotelapartment.com; map p179. Spotless new hotel apartments recently opened by the same friendly and enterprising family that runs the restaurant of the same name next door. Each comes with a kitchen, and the most spacious apartments sleep four (45 OR). A breakfast buffet is served in the upstairs restaurant, while downstairs beside the reception is Sur’s brightest little cafe (open 24hr). Unfortunately for light sleepers, there’s a large mosque just across the street – best to avoid the apartments facing north. 35 OR

EATING

There’s not much in the way of culinary diversion in Sur, and only a pair of licensed venues: Oysters at the Sur Plaza Hotel and Cheers Bar, a smoky sports bar attached to the Sur Holiday Beach Resort.

Oysters Restaurant Sur Plaza Hotel ![]() 2554 3777; map. Facing the pool of Sur’s top hotel, this is the most upmarket restaurant in town (and the only one that’s licensed), with a wide-ranging international menu and nightly buffet (8 OR) that features Indian, Chinese and Italian cuisines. Daily 6am–11.30pm.

2554 3777; map. Facing the pool of Sur’s top hotel, this is the most upmarket restaurant in town (and the only one that’s licensed), with a wide-ranging international menu and nightly buffet (8 OR) that features Indian, Chinese and Italian cuisines. Daily 6am–11.30pm.

Sahari Restaurant Next to the Al Ayjah Plaza Hotel ![]() 2554 1423; map. The restaurant and its spacious outdoor terrace boast a fine location overlooking the lagoon, offering a mishmash menu of seafood, Indian and Arabian cuisines (mains 1.5–7 OR), as well as greasy fatayir (from 1 OR), pizzas (from 2 OR) and desserts. Daily 8.30am–1am.

2554 1423; map. The restaurant and its spacious outdoor terrace boast a fine location overlooking the lagoon, offering a mishmash menu of seafood, Indian and Arabian cuisines (mains 1.5–7 OR), as well as greasy fatayir (from 1 OR), pizzas (from 2 OR) and desserts. Daily 8.30am–1am.

Sur Sea Restaurant Town centre, just west of Sur Hotel ![]() 9212 6096; map. The best of the many café-cum-restaurants scattered around the souk, serving up reasonable, well-priced food in a lively streetside seating – a great place for people-watching. The menu features the usual mix of quasi-Indian dishes and shwarmas (from 0.3 OR), plus some worthy seafood options (jumbo prawns 4 OR). Daily 7.30am–3am.

9212 6096; map. The best of the many café-cum-restaurants scattered around the souk, serving up reasonable, well-priced food in a lively streetside seating – a great place for people-watching. The menu features the usual mix of quasi-Indian dishes and shwarmas (from 0.3 OR), plus some worthy seafood options (jumbo prawns 4 OR). Daily 7.30am–3am.

Zaki 1km west of the centre, just behind Zaki Hotel Apartments ![]() 2554 4249; map. Popular, family-run place serving up some of Sur’s top South Asian cuisine (chicken masala 1.2 OR) along with excellent seafood (grilled fish from 2.5 OR). The large, adjacent mosque ensures that it’s particularly packed on Friday afternoons. Free delivery. Daily 6am–1am.

2554 4249; map. Popular, family-run place serving up some of Sur’s top South Asian cuisine (chicken masala 1.2 OR) along with excellent seafood (grilled fish from 2.5 OR). The large, adjacent mosque ensures that it’s particularly packed on Friday afternoons. Free delivery. Daily 6am–1am.

DIRECTORY SUR

Banks and money There are numerous banks with ATMS along the main road and particularly within the souk.

Health There are several pharmacies along the main road into town and through the souk, including Ibn Sina (daily 8am–1pm & 4–10pm), 100m north of the Sur Hotel.

The eastern coast of Sharqiya ends with a watery flourish at the little village of RAS AL HADD, sitting at the far southeastern corner of the country, overlooking the point where the waters of the Arabian Gulf merge with the Indian Ocean. The village’s main attraction is as a convenient base from which to explore the turtle beach at Ras al Jinz, although it’s well worth a visit in its own right thanks to its pleasantly sleepy, somewhat end-of-world feeling, and impressive old fort, backed by a pair of extensive lagoons.

Ras al Hadd fort

Mon–Thurs & Sun 8.30am–2.30pm • Free

The main sight hereabouts is the sprawling fort, close to the sandy shore, looking (along with the rather grand mosque next door) incongruously oversized compared to the tiny buildings of the rustic village that surrounds it. Most of the interior consists of a huge empty courtyard, with a walkway stretching the length of the parapet and a large round tower at either end, each with a neat little toilet projecting from its topmost level.

ACCOMMODATION RAS AL HADD

Turtle Beach Resort 3km east of town ![]() 9900 7709,

9900 7709, ![]() tbroman.com. This old resort was recently given a new lease of life upon moving across the lagoon to a new location. Accommodation is in traditionally furnished chalets with tented roofs and patios shaded with palm fronds. All are en suite and equipped with a/c and flat-screen TVs. There’s a licensed restaurant on-site, and perhaps best of all, it’s set right beside a pretty cove. To reach the resort, head straight north through the roundabout at the entrance to the village, past the Al Maha petrol station, and follow this road to the end (about 5km), just beyond Ras al Hadd Holiday Resort. Half board costs an extra 2.5 OR per person. 60 OR

tbroman.com. This old resort was recently given a new lease of life upon moving across the lagoon to a new location. Accommodation is in traditionally furnished chalets with tented roofs and patios shaded with palm fronds. All are en suite and equipped with a/c and flat-screen TVs. There’s a licensed restaurant on-site, and perhaps best of all, it’s set right beside a pretty cove. To reach the resort, head straight north through the roundabout at the entrance to the village, past the Al Maha petrol station, and follow this road to the end (about 5km), just beyond Ras al Hadd Holiday Resort. Half board costs an extra 2.5 OR per person. 60 OR

Ras al Jinz and the southern coast

Some 17km onwards from Ras al Hadd – at the easternmost point of the Arabian peninsula – is RAS AL JINZ, home to Oman’s most important turtle-nesting beach, visited by thousands of magnificent green turtles every year, hauling themselves up out of the sea to lay their eggs in the sand. This is perhaps the finest natural spectacle anywhere in Oman (even if, ironically, you can’t actually see very much after dark) – a magical glimpse into a natural cycle which has been in existence for the best part of two hundred million years.

Visits begin at the smart, modern visitor centre, where you’ll be assigned a group and wait for a guide to scan the beach. In the meantime, you can peruse the small but informative museum (daily 9am–9pm; 2 OR), documenting the life cycle of the turtles. Towards the end there’s a tank sometimes containing tiny newborn turtles that were lost on their way to the sea that day. They are then taken back to the beach after sunset, when the cover of darkness allows them safer passage to sea.

When your guide gives the green light, you’ll walk across the sands in the darkness to the edge of the waves, from where you’ll see the ghostly silhouettes of perhaps a dozen or more green turtles emerging slowly from the surf and then heaving themselves laboriously up the beach – a Herculean trial of strength for these enormously heavy creatures. Half an hour later, having found a suitably sheltered location, the turtles begin digging themselves carefully into the beach, scooping out clouds of sand with their flippers to create a sizeable hole in which they then proceed to lay their eggs.

RAS AL JINZ: WHEN TO VISIT

The best time to see turtles laying their eggs is from June to August, when anything up to a hundred may arrive on the beach each night (although you’re pretty much guaranteed to see at least one or two come to lay their eggs on any night of the year). Nesting turtles prefer dark nights rather than those when the moon is full.

The whole scene is particularly magical at daybreak, as the sun rises, revealing the beautiful, cliff-fringed beach dotted with the great humped outlines of departing turtles, leaving great plough-tracks in their wake as they make their way slowly back down the beach before disappearing, exhausted, into the waves.

ARRIVAL AND TOURS RAS AL JINZ

By car Ras al Jinz is 45km (a 40min drive) southeast of Sur, and about 80km (1hr 10min) north of Al Ashkharah.

By taxi Most hotels in Sur can arrange round-trip transport for around 20–25 OR per person.

Tours Tours to the 3km-long beach (part of a larger 45km protected zone) are strictly controlled, with a maximum of 200 visitors per evening and another 100 visitors per morning session. Unfortunately, demand for outstrips supply, and bookings either by phone or email are essential; three weeks or more in advance is recommended since spaces usually get booked up early, even for early-morning tours and in the height of summer – you won’t be charged if there are no turtles nesting at the time of your visit. Tours depart from the visitor centre (![]() 9655 0606,

9655 0606, ![]() rasaljinz-turtlereserve.com) at 9pm and 4am, last around 1hr–1hr 30min and cost 7 OR. No torches or photography (even without flash) are allowed on night tours, while photography is allowed on morning tours only after sunrise.

rasaljinz-turtlereserve.com) at 9pm and 4am, last around 1hr–1hr 30min and cost 7 OR. No torches or photography (even without flash) are allowed on night tours, while photography is allowed on morning tours only after sunrise.

ACCOMMODATION

Al Naseem Camp 4km inland from the visitor centre, next to the road ![]() 9200 9427,

9200 9427, ![]() desertdiscovery.com/al-naseem-camp.html. A cheaper but less pleasant alternative to staying at the visitor centre, with accommodation in a compound of a/c palm-thatch huts and cabins, with no furniture apart from beds; all share rudimentary shower and toilet facilities. Rates include half board. Per person 25 OR

desertdiscovery.com/al-naseem-camp.html. A cheaper but less pleasant alternative to staying at the visitor centre, with accommodation in a compound of a/c palm-thatch huts and cabins, with no furniture apart from beds; all share rudimentary shower and toilet facilities. Rates include half board. Per person 25 OR

Ras al Jinz Turtle Reserve Visitor centre ![]() 9655 0606,

9655 0606, ![]() rasaljinz-turtlereserve.com. The most convenient way to see the turtles is to say at the reserve itself. The visitor centre houses seventeen comfortable modern rooms, while a couple of minutes’ walk down a cul-de-sac are twelve air-conditioned “eco-tents,” by far the most luxurious option around. Rates include breakfast while the dinner buffet costs 8 OR, and your room key functions as your ticket to the museum and both evening and morning tours. Doubles 92 OR, tents 125 OR

rasaljinz-turtlereserve.com. The most convenient way to see the turtles is to say at the reserve itself. The visitor centre houses seventeen comfortable modern rooms, while a couple of minutes’ walk down a cul-de-sac are twelve air-conditioned “eco-tents,” by far the most luxurious option around. Rates include breakfast while the dinner buffet costs 8 OR, and your room key functions as your ticket to the museum and both evening and morning tours. Doubles 92 OR, tents 125 OR

Asaylah and around

South of Ras al Jinz it’s a pleasant drive along the coast through a string of small, ramshackle villages. The landscape beyond Asaylah is particularly beautiful, with an unusual combination of mountain and desert, as the craggy limestone outcrops at the far southern end of the Eastern Hajar merge with the outlying dunes (some of them surprisingly large) of the Sharqiya Sands.

Al Ashkharah to Shana

A short drive beyond Asaylah and some 90km from Ras al Jinz, AL ASHKHARAH is the largest settlement along this stretch of coast, although not really much more than a tumbledown little fishing town with low ochre-coloured houses straggling along a wide stretch of beach.

There’s a choice of routes from Al Ashkharah: either northwest along Highway 35 to Jalan Bani Bu Ali and on to Ibra, or south along the scenic coastal road to Shana, the departure point for ferries to Masirah, a journey of some 180km. The drive to Shana takes 1hr 30min–2hr along the fast single-carriageway road; there are several petrol stations along the way, but they don’t always have fuel – best to fill up before leaving Al Ashkharah. It’s a fine drive, with pleasant coastal scenery including a stretch of large rolling dunes beyond Khuwaymah (and with brief, distant glimpses of the high dunes of the Sharqiya Sands rising further inland). The region is totally uninhabited apart from the ramshackle Bedu camps you’ll see pitched alongside the road, from which children may occasionally emerge to chuck stones at passing traffic.

ACCOMMODATION AL ASHKHARAH TO SHANA

Al Ashkhara Beach Resort 16km south of Al Ashkhara ![]() 9408 2424,

9408 2424, ![]() ashkhara.com. All alone facing a pretty stretch of white sand, with spacious, comfortable rooms and suites with private, trellis-roof terraces, some of which overlook the sea. It’s a popular weekend getaway spot for families from Muscat, who take advantage of the pool, the playground and the activities on offer – jetskiing, fishing, horseback riding – while ensuring that the on-site restaurant stays open. At other times, however, it can be as quiet and lonely as its desolate surrounds. No wi-fi. 30 OR

ashkhara.com. All alone facing a pretty stretch of white sand, with spacious, comfortable rooms and suites with private, trellis-roof terraces, some of which overlook the sea. It’s a popular weekend getaway spot for families from Muscat, who take advantage of the pool, the playground and the activities on offer – jetskiing, fishing, horseback riding – while ensuring that the on-site restaurant stays open. At other times, however, it can be as quiet and lonely as its desolate surrounds. No wi-fi. 30 OR

Al Ashkhara Hotel On the west side of the main road through Al Ashkhara, about 100m south of the Shell station. This run-down one-star has seen better days (probably in around 1950) but is tolerably clean and will do for a night if you get stuck. The central location means there are loads of (nearly identical) restaurants around – the Golden Beach Restaurant and Coffee House next door does good set dinners. 12 OR

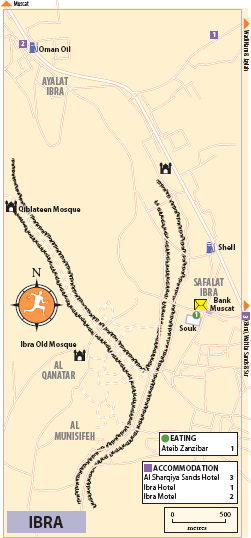

The principal town of inland Sharqiya, IBRA grew rich thanks to its location on the major trade route between Muscat, Sur and Zanzibar. Evidence of the wealth accumulated by the town’s former notables can be seen in the magnificent old mudbrick mansions of Al Munisifeh, while the dozen or so watchtowers – standing guard on the jagged hilltops overlooking the approaches to town – remind of Ibra’s one-time strategic importance. The town is also the home of the redoubtable Al Harthy tribe, whose repeated rebellions against the sultans of Muscat were such a feature of early twentieth-century Omani history.

Modern Ibra has regained a good share of its historical importance. It’s home to a technical college, a university, a large regional hospital and its very own Lulu Hypermarket, while the expansion of the new expressway promises to bring the rest of the country even closer.

Ayalat Ibra (Upper Ibra) – the modern town – is strung out along the main highway, a functional ribbon of banks, petrol stations and cafés. It’s around 3km south of here to the older part of town, Safalat Ibra (Lower Ibra), which is where you’ll find the lively souk, one of the largest in Sharqiya. Just west of here are the crumbling remains of Al Munisifeh and Al Qanatar, featuring some of the region’s finest traditional mudbrick architecture. Ibra also makes a good base for explorations of the nearby Sharqiya Sands, as well as a possible starting point for the magnificent off-road drive to the coast via the tombs of Jaylah.

Ibra souk

600m west of the main highway in Safalat Ibra: take the turning signed Safalat Ibra directly south of the Shell station

The heart of Ibra’s old souk is occupied by a large open-air pavilion mainly given over to the sale of fruit and vegetables. Look out for the small shop in the corner devoted to the (as the sign says) “Sale of Traditional Rifle Maintenance and Fire Arms”, usually busy with a few old-timers bent over antiquated-looking weapons. There are also a few shops selling jewellery and khanjars, while the block immediately beyond the central pavilion is occupied by a string of carpentry shops turning out old-fashioned wooden doors and other traditional wooden items, although the workforce is now exclusively Indian.

Held close to the main souk on Wednesday mornings from around 7am to 11am

Ibra is also home to a celebrated Women’s Souk (Souk al Hareem, or Souk al Arba’aa, meaning “Wednesday souk”). The souk is restricted to female traders and shoppers (in theory at least – the rule is not strictly enforced), with a wide selection of goods ranging from piles of cheap clothes and factory cloth through to traditional cosmetics and textiles; look for examples of the colourful and distinctive local Bedu embroidery which is sewn onto black abbayat or around the ankles of trousers.

Al Munisifeh

To reach the villages, continue south past the souk until the road veers to the left, then turn right, following the brown signs to Al Munisifeh Village, Al Qanatar Village and Al Qablateen Mosque

A couple of kilometres beyond Ibra souk lie the atmospheric old walled villages of Al Munisifeh and Al Qanatar, two of the finest in the region. Approaching by road, you come first to AL MUNISIFEH, surrounded by the remains of its original walls, with gateways at either side linked by a central street. The village comprises an assortment of modern houses interspersed with rather grand old buildings in a mix of mudbrick and stone – their size testifying to the wealth amassed by the village’s merchants during Ibra’s heyday athwart the trade route between Muscat and Zanzibar.

SIGN LANGUAGE, OMAN STYLE

One charmingly old-fashioned aspect of every souk in Oman is the lack of advertising. Visit any market in the country and you’ll see lines of similar little shops all boasting exactly the same, resolutely factual, signs in Arabic, with their English translations below. “Coffee Shop” is probably the most common, closely followed by “Gents Tailoring” (with “Ladies Tailoring” not far behind), while other signs are similarly matter of fact – “Sale & Repairing of Dish & Television” for a TV shop, for instance, or “Sale of Fresh Mutton & Frozen”. The accuracy of English translations is consistently high, and mistakes rare, although when things do go wrong they can do so spectacularly, such as the shop in Ibra souk advertising “Asle of Freah Ghigken” (“Sale of Fresh Chicken”). Occasionally bursts of unintentional linguistic whimsy also catch the eye, notably the local outlet advertising “Sale of Tobacco, Smoke & Derivatives” – a pleasantly fanciful way of saying they sell cigarettes.

The quality of the decorative work on many of the old houses is unusually high – look out for the remains of elaborate plasterwork, and finely carved wooden doorways and window frames. It’s best to park before Munisifeh and follow the road through town, ducking off to explore the old buildings along the way. Virtually all are now uninhabited and partially derelict, although some have been discreetly restored, which has managed to preserve much of their original character while giving the comforting sense (unlike so many other abandoned Omani houses) that they aren’t in danger of collapsing in the next heavy shower.

Al Qanatar

Emerging from Munisifeh along the main street, you’ll wind through the fields for about 300 metres before reaching Al Qanatar, just beyond the remains of the old souk that lie off to the left of the road. Just beyond here, also on the left, a narrow street leads to Al Qanatar’s restored old mudbrick mosque, raised on a platform above street level. As with similar very early mosques elsewhere in the country, such as the Masjid Mazari in Nizwa, there’s no minaret, just a tiny pepperpot dome on one corner. Non-Muslims aren’t allowed to enter to see the fifteen stumpy columns massed inside, strikingly similar to those at the Al Hamooda Mosque in Jalan Bani Bu Ali. Carry on along Al Qanatar’s narrow main street, hemmed in between two-storey mud-brick houses, to find further hints of its former glory, with dozens of more beautifully carved, dilapidated doorways.

Al Qiblateen Mosque

Follow the wadi bed north past Al Qanatar to reach the venerable old Al Qiblateen Mosque (“Mosque of the Two Qiblas”), about ten minutes away on foot. Little more than a stone cube on the hillside, its importance lies in being perhaps the oldest mosques in the country, as evidenced by the small niche in the far left corner, an obvious afterthought in the structure’s design. While this mihrab points roughly towards Mecca, the original one (on the far wall) was apparently built before Muhammad’s injunction to stop praying towards Jerusalem. Dress conservatively when entering, and don’t be fooled by the nearly identical structure about 200 metres south – you can count the niches to be sure.

ACCOMMODATION IBRA AND AROUND

Ibra has a few decent accommodation options; there are also a couple of places further south along the main road to Sur, or you can head to one of the many desert camps within the Sharqiya Sands.

Al Sharqiya Sands Hotel 8km south of Ibra on the west side of Highway 23, just south of the turn-off to Sinaw and Al Mudaybi ![]() 2558 7099,

2558 7099, ![]() sharqiyasands.com; map. A pleasant spot just outside of Ibra, with accommodation in clean though rather tired rooms set around a green courtyard with a decent-sized pool. There’s a good licensed restaurant serving mostly Indian food, a cosy pub and a noisy cabaret hall with nightly dance and music performances next door. 42 OR

sharqiyasands.com; map. A pleasant spot just outside of Ibra, with accommodation in clean though rather tired rooms set around a green courtyard with a decent-sized pool. There’s a good licensed restaurant serving mostly Indian food, a cosy pub and a noisy cabaret hall with nightly dance and music performances next door. 42 OR

Ibra Hotel 500m east of the Wadi Nam roundabout

Ibra Hotel 500m east of the Wadi Nam roundabout ![]() 2557 1873, Eibrahotel@gmail.com; map. This centrally located hotel has clean, simply-furnished rooms lining a bright, open-air central hallway that leads to a big swimming pool out back, beside which is a decent restaurant. In the complex out front, there’s a smoky bar with a pool table and a big, echoing music hall that hosts nightly performances. 30 OR

2557 1873, Eibrahotel@gmail.com; map. This centrally located hotel has clean, simply-furnished rooms lining a bright, open-air central hallway that leads to a big swimming pool out back, beside which is a decent restaurant. In the complex out front, there’s a smoky bar with a pool table and a big, echoing music hall that hosts nightly performances. 30 OR

Ibra Motel 750m west of the Wadi Nam roundabout, behind the Oman Oil petrol station ![]() 2557 1666, Eibramtl@omantel.net.com; map. One of the nicest budget hotels in southern Oman, with smart, spacious and very attractively furnished rooms at bargain prices. 22 OR

2557 1666, Eibramtl@omantel.net.com; map. One of the nicest budget hotels in southern Oman, with smart, spacious and very attractively furnished rooms at bargain prices. 22 OR

Shutterstock

WADI TIWI

Outside of the main hotels, Ibra’s restaurant scene is mostly limited to no-frills coffee shops. For picnic supplies, visit the deli at Lulu Hypermarket. Al Sharqiya Sands Hotel and Ibra Hotel have the city’s only licensed venues.

Ateib Zanzibar Just north of Ibra souk ![]() 9212 6096; map. Cheap and cheery little spot to fill up after wandering the souk, with hot, greasy South Asian-inspired snacks like vegetable, fish and chicken cutlets (100bz) and sambusa (50bz). The menu is in Arabic only, though it’s easy enough to point out what you’d like through the glass partition. Daily 8am–1pm & 4.30–10pm.

9212 6096; map. Cheap and cheery little spot to fill up after wandering the souk, with hot, greasy South Asian-inspired snacks like vegetable, fish and chicken cutlets (100bz) and sambusa (50bz). The menu is in Arabic only, though it’s easy enough to point out what you’d like through the glass partition. Daily 8am–1pm & 4.30–10pm.

Sinaw

Pressed against the far western edge of Northern Sharqiya, about 90km west of Ibra and 80km south of Izki, the town of SINAW makes a worthy diversion from the beaten path running from Ibra to the coast. Its remoteness is certainly part of the charm – other than being a stop on the long inland highway running the length of Sharqiya and on to Duqm and the Al Wusta coast, it’s not quite on the way to anywhere, and thus sees very few foreign visitors. Its lively souk, however, remains one of the most interesting in the entire region.

Sinaw souk

The souk is in the centre of town; turn left at the big roundabout if approaching from Ibra via Al Mudaybi or from Izki centre

Sinaw is best known for its colourful souk – a rectangle of shops arranged around a large courtyard with an open-sided pavilion in the middle. The souk attracts large numbers of Bedu from the nearby Sharqiya Sands, including local women dressed in vibrantly coloured shawls, patchwork tunics and embroidered anklets, and others, less flamboyant, swathed in black abbayat and face masks. It’s particularly lively on Thursday mornings during the weekly livestock market.

Old Sinaw

Tucked away in the extensive date plantations to the south of the souk lie the atmospheric remains of old Sinaw, comprising a pair of neat little villages nestled among the palms. The first is close behind the souk, while the second lies further into the plantations; both are crammed with fine two- and three-storey mudbrick buildings, some surprisingly well preserved.

Mudayrib

Some 18km south of Ibra, a sign points left off Highway 23 to MUDAYRIB. One of the prettiest villages in Sharqiya, Mudayrib is surrounded by an unusually fine cluster of six watchtowers on the encircling hills, which form a tight protective necklace around the small village below, all beautifully backdropped by the craggy peaks of the Eastern Hajar. The village boasts a number of imposing old fortified houses built, as at Ibra, by merchants who had grown wealthy on the back of trade with Africa. Some of them look almost like miniature forts, with battlemented rooftops, miniature towers and musket slits in the walls.

Al Wasil

About 16km south along the old highway from Mudayrib is the town of AL WASIL, its centre less than a couple of kilometres from the wall of dunes towering to the west – it’s the access point for several camps in the Sharqiya Sands. Signs along the highway direct towards the old castle in the centre of town, partially restored in recent years though not the most interesting of the area’s forts. A few openings in the walls allow you to walk in and explore the interior courtyard, sometimes used to host local events.

Arabia’s most iconic inhabitants, the Bedu (often Anglicized to “Bedouin”) have long been seen – by Westerners at least – as the human face of the desert peninsula. For outsiders, the Bedu have come to personify a rather romanticized ideal of nomadic life amid the sands, with their distinctive lifestyle of ferocious independence, ceaseless tribal feuds and outbursts of legendary hospitality. Some of which is at least partly true.

Scattered across the interior of Oman and other countries around the peninsula, the nomadic Bedu tribes formerly eked out a marginal existence amid one of the world’s most hostile natural environments, surviving in the depths of the desert by a combination of camel-raising, goat-herding and inter-tribal raiding – a lifestyle founded on a complex network of tribal allegiances, intimate knowledge of the local environment and extraordinary levels of physical resilience. Wilfred Thesiger’s Arabian Sands remains essential reading for anyone with even a cursory interest in the region, offering a fascinating glimpse into the Bedu tribes’ unique customs and traditions and a salutary corrective to some of the more flowery received notions of nomadic life.

Not surprisingly, virtually nothing survives of the harsh traditional Bedu existence described by Thesiger. Many Bedu in Oman have adopted settled, sedentary lifestyles, emigrating to the cities and merging with the population at large, while others have reinvented themselves as tour guides, offering modern visitors rewarding insights into the flora, fauna and traditional culture of the Sharqiya Sands. Traditional Bedu culture and customs do, however, linger on in many parts of southern Oman, particularly around the Sands themselves. Local Bedu here still follow a modified form of their traditional pursuits, raising livestock for part of the year before decamping to their plantations around Mintrib to harvest dates during the hot summer months. Bedu families can also often be seen frequenting the souks of Ibra and Sinaw, with the distinctive sight of local Bedu women in traditional face masks and elaborately embroidered shawls, trousers and tunics offering a colourful reminder of the interior’s traditional, if now increasingly threatened, past.

Mintrib

Some 10km south of Al Wasil and about 2km west of the old highway is the little town of MINTRIB (also spelled Mintarib and Minitraib), home to a small, stout castle. The town is an important access point for the Sharqiya Sands, which rise immediately behind. Guides typically wait around in the car park outside the castle, offering tours of the sands (20/30 OR for half-hour/hour-long tours). There’s a handy garage in the middle of town where you can have your tyre pressure reduced before venturing onto the sands.

Mintrib Castle

Main Street • Mon–Thurs & Sun 7.30am–2.30pm • 500bz

Built in in the early seventeenth century and expanded in the late eighteenth by Imam Azzan bin Qais, this newly renovated fort features unusual, slightly inward-sloping walls and a single, undernourished tower rising just a metre or so above the battlements. Centred on a well, the ground-floor courtyard has many of the standard features: a low-entry jail, small mosque, majlis, weapons cache and “murder hole” above the entrance (look up to see the narrow slit through which boiling date syrup was dropped on unwanted visitors). The first floor is more unique, with four thirty-metre vaulted corridors, impressive for having been built entirely without timber and lit in part by rifle slits notched into the outer walls. Climbing to the rooftop affords worthwhile views of the dunes rising behind the date palm oasis to the west.

South of Ibra stretch the magnificent Sharqiya Sands (Ramlat al Sharqiya; also known as the Wahiba Sands) – “a perfect specimen of sand sea”, as they have been described. This is the desert as you’ve always imagined it: a huge, virtually uninhabited swathe of sand, with towering dunes, reaching almost 100m in places, sculpted by the wind into delicately moulded crests and hollows. Tourist resorts apart, there are no permanent settlements in the sands, although some local Bedu still live here in somewhat ramshackle temporary encampments, particularly on the southern fringes of the sands around Al Ashkharah. Otherwise, they remain hauntingly empty, although the endless tracks churned up by cavorting dune-bashers tearing around the sands in their souped-up 4WDs (and, along the main routes, obscene quantities of litter) mean that it’s not quite as unspoiled as you’d expect. As a general rule of thumb, the further into the sands you penetrate, the more dramatic and untouched the landscape becomes.

The dunes themselves follow a surprisingly regular pattern, as a glance at Google Earth makes strikingly clear, running in long lines from north to south – an orderly sequence of so-called “linear” dunes formed by the conflicting winds blowing in from the eastern and southern coasts (and meaning that travelling across the sands from north to south is significantly easier than tackling them from east to west). They are also constantly on the move, shifting inland at an estimated rate of 10m per year.

For many visitors, overnighting amid the Sharqiya Sands at a desert camp is one of Oman’s most memorable experiences – surrounded by the majestic outline of moonlit dunes, and with a twinkling tapestry of stars overhead.

GETTING AROUND THE SHARQIYA SANDS

By car The sands cover a considerable area: some 180km from north to south, and almost 80km from east to west. There are no roads in the Sharqiya Sands. A network of tracks (for which you’ll need 4WD) crisscrosses the sands, although these are sometimes difficult to follow without local knowledge, being notional routes rather than physical tracks – meaning it’s possible to get badly lost if you don’t know what you’re doing. Getting stuck in the desert is also a real possibility, and no laughing matter during the hot summer months; it’s best to travel with at least one other vehicle if you’re venturing away from established routes.

ACCOMMODATION

You don’t get much for your money at any of the extensive string of desert camps dotting the dunes. Even the most basic camps come with a sizeable mark-up, while the nicer spots can cost as much as a plush Muscat five-star hotel. On the plus side, rates include breakfast and dinner, plus free coffee, tea and fruit. Most camps feature accommodation in some kind of pseudo-traditional tent or palm-thatch hut (which may be concrete inside). It’s also worth bearing in mind that you can explore the sands without actually overnighting in them, either by staying in or around Ibra or along the highway further south at Oriental Nights Rest House or Qawafel Al Mamoorh.

Getting to the desert camps You’ll need a 4WD to reach all the desert camps apart from Al Areesh and Al Reem (see below), although all places can arrange to collect you from the main road, albeit often at a considerable price. Desert Nights Camp, Nomadic Desert Camp and Sama Al Wasil Tourism Village are reached from Al Wasil village, 30km south of Ibra; 1000 Nights and Al Raha are reached from Mintrib, 40km south of Ibra; Al Reem is much further south, near Jalan Bani Bu Hassan.

DESERT ECOLOGY IN THE SHARQIYA SANDS

Empty though they may look, the sands support a fascinating desert ecology. A celebrated expedition by the Royal Geographical Society in 1986 discovered 150 species of plant, including the hardy ghaf (Proposis cinera), which plays a major role in stabilizing the dunes, as well as providing firewood and shade. In addition, 200 mammal, bird and reptile species were discovered, ranging from side-winding vipers to desert hares and sand foxes. Most of these creatures are nocturnal, however, so you’re unlikely to see much during the day apart from their tracks.

The principal attraction of a visit here is simply the chance to be out among the dunes, and to spend a night in the desert. All the desert camps lay on various desert activities. Dune-bashing is a popular, if not particularly restful or environmentally friendly, way of exploring the sands; camel or horse rides (sometimes guided by local Bedu) offer a more peaceful alternative – expect to pay about 15 OR per hour. Other activities include sandboarding, trekking and quad-biking.

When to visit Many places can get noisy at weekends, when locals and expats descend on the region; if possible, visit during the week.

1000 Nights 20km further into the sands beyond Al Raha camp T9944 8158, ![]() 1000nightscamp.com. Set deep in the sands, this camp’s accommodation ranges from pleasantly authentic Bedu-style tents to unabashed glamping. The standard “Arabic” tents are relatively bare, little more than a couple of beds and a shared bathroom; at the next tier are the larger “Sheikh” tents, which come with nice open-air toilets and showers, while the much pricier glass-walled, a/c “Ameer” tents are even bigger, with attractive woven decorations, a couple of pieces of furniture and hot water; or there’s more conventionally comfortable accommodation in the pair of two-storey, a/c “Sand Houses”, built in traditional mudbrick style. Facilities include a small but pretty pool and mudbrick-style sun terrace, a quirky sit-out area in an old dhow, and a lovely (unlicensed) restaurant scattered with colourful cushions. Pick up from Mintrib is 40 OR return. Arabic tent 49 OR, Sheikh tent 76 OR, Ameer Tent 148 OR, Sand House 172 OR

1000nightscamp.com. Set deep in the sands, this camp’s accommodation ranges from pleasantly authentic Bedu-style tents to unabashed glamping. The standard “Arabic” tents are relatively bare, little more than a couple of beds and a shared bathroom; at the next tier are the larger “Sheikh” tents, which come with nice open-air toilets and showers, while the much pricier glass-walled, a/c “Ameer” tents are even bigger, with attractive woven decorations, a couple of pieces of furniture and hot water; or there’s more conventionally comfortable accommodation in the pair of two-storey, a/c “Sand Houses”, built in traditional mudbrick style. Facilities include a small but pretty pool and mudbrick-style sun terrace, a quirky sit-out area in an old dhow, and a lovely (unlicensed) restaurant scattered with colourful cushions. Pick up from Mintrib is 40 OR return. Arabic tent 49 OR, Sheikh tent 76 OR, Ameer Tent 148 OR, Sand House 172 OR

Al Areesh Turn-off from Highway 23 around 27km south of Ibra (7km past Mudayrib turn-off), then 8km into the sands ![]() 9200 9427,

9200 9427, ![]() desertdiscovery.com/al-areesh-desert-camp.html. Built in the lee of the dunes in a rather tame section of desert, this is one of the oldest and drabbest of the main camps, its main selling points being that it’s relatively cheap and accessible by sealed road (apart from the last 750m or so, which should be fine in a 2WD), although this means the scenery is less majestic than at other places further into the dunes. Accommodation is in basic huts and Bedouin tents covered in withered palm fronds, all fitted with electric lighting and shared toilet facilities – alternatively, you can move your bed and sleep outside. Expensive for what you get. Per person 25 OR

desertdiscovery.com/al-areesh-desert-camp.html. Built in the lee of the dunes in a rather tame section of desert, this is one of the oldest and drabbest of the main camps, its main selling points being that it’s relatively cheap and accessible by sealed road (apart from the last 750m or so, which should be fine in a 2WD), although this means the scenery is less majestic than at other places further into the dunes. Accommodation is in basic huts and Bedouin tents covered in withered palm fronds, all fitted with electric lighting and shared toilet facilities – alternatively, you can move your bed and sleep outside. Expensive for what you get. Per person 25 OR

Al Raha 20km along the road past Mintrib Fort ![]() 9700 3222,

9700 3222, ![]() facebook.com/pg/alrahacampoman. Set a considerable distance into the sands in a neat and shady little garden surrounded by towering dunes, Al Raha offers perhaps the best value of the various camps. Accommodation is in rather unappealing concrete rooms (all en suite), some with a/c. There’s a licensed restaurant and free tea and coffee served in the majlis. Round-trip transport for those without 4WD costs 30 OR. 20 OR

facebook.com/pg/alrahacampoman. Set a considerable distance into the sands in a neat and shady little garden surrounded by towering dunes, Al Raha offers perhaps the best value of the various camps. Accommodation is in rather unappealing concrete rooms (all en suite), some with a/c. There’s a licensed restaurant and free tea and coffee served in the majlis. Round-trip transport for those without 4WD costs 30 OR. 20 OR

Al Reem About 3km west of Highway 35, signed about 4km north of Jalan Bani Bu Hassan

Al Reem About 3km west of Highway 35, signed about 4km north of Jalan Bani Bu Hassan ![]() 9174 0009,

9174 0009, ![]() alreem-desertcamp.com. In a wooded area on the edge of the desert near Jalan Bani Bu Hassan, this relatively new desert camp is one of the easiest to access from the road – only the last few minutes requires going off the pavement and over some scrub, which should present no problems for a 2WD. In addition to the basic, simply furnished tents there are options with all the mod cons, from standard rooms to a range of charmingly decorated tent and bungalow suites, including some for families of four (68 OR). Thoughtful, energetic staff provide a warm welcome, good food and occasional entertainment around a bonfire at night. Doubles 50 OR, basic tents 42 OR, tent suites 58 OR

alreem-desertcamp.com. In a wooded area on the edge of the desert near Jalan Bani Bu Hassan, this relatively new desert camp is one of the easiest to access from the road – only the last few minutes requires going off the pavement and over some scrub, which should present no problems for a 2WD. In addition to the basic, simply furnished tents there are options with all the mod cons, from standard rooms to a range of charmingly decorated tent and bungalow suites, including some for families of four (68 OR). Thoughtful, energetic staff provide a warm welcome, good food and occasional entertainment around a bonfire at night. Doubles 50 OR, basic tents 42 OR, tent suites 58 OR

Desert Nights Camp Turn-off from Al Wasil, then 11km into the sands ![]() 9281 8388,

9281 8388, ![]() omanhotels.com/desertnightscamp. Certainly among the most luxurious camps in the Sharqiya Sands, offering a real dash of Arabian style in the desert, although at a hefty price. Accommodation is in a string of individual “units” modelled after traditional Arabian tents, attractively furnished with traditional bric-a-brac and fabrics under a tent-style canvas roof, some of them large enough to sleep four (220 OR); standard rooms are cheaper but not nearly as nice. There’s also an attractive licensed restaurant (with a live oud player nightly) and a nice bar, plus complimentary pick-up from the main road and a sunset ride through the dunes. Doubles 115 OR, tent suites 130 OR

omanhotels.com/desertnightscamp. Certainly among the most luxurious camps in the Sharqiya Sands, offering a real dash of Arabian style in the desert, although at a hefty price. Accommodation is in a string of individual “units” modelled after traditional Arabian tents, attractively furnished with traditional bric-a-brac and fabrics under a tent-style canvas roof, some of them large enough to sleep four (220 OR); standard rooms are cheaper but not nearly as nice. There’s also an attractive licensed restaurant (with a live oud player nightly) and a nice bar, plus complimentary pick-up from the main road and a sunset ride through the dunes. Doubles 115 OR, tent suites 130 OR

Nomadic Desert Camp Turn-off at Al Wasil, then 20km into the sands ![]() 9933 6273,

9933 6273, ![]() nomadicdesertcamp.com. A long-established camp deep in the sands, owned and operated by a local Bedu family and therefore offering a touch of authenticity other places lack. Accommodation is in simple but nicely furnished barasti huts, with shared bathroom only and no electricity, and there’s an attractive majlis-cum-dining area. They also offer complimentary camel rides and round-trip transport from Al Wasil (10 OR per person). Per person 35 OR

nomadicdesertcamp.com. A long-established camp deep in the sands, owned and operated by a local Bedu family and therefore offering a touch of authenticity other places lack. Accommodation is in simple but nicely furnished barasti huts, with shared bathroom only and no electricity, and there’s an attractive majlis-cum-dining area. They also offer complimentary camel rides and round-trip transport from Al Wasil (10 OR per person). Per person 35 OR

Sama Al Wasil Tourism Village Turn-off from Al Wasil, then 15km into the sands ![]() 2449 9309,

2449 9309, ![]() samavillages.com. Newish and well-equipped camp with accommodation in a neat circle of attractive sandstone chalets and tents (all en suite) in traditional Omani style, with pretty little rug-covered verandas. It lacks some of the atmosphere of more traditional tented camps, but compensates with above-average creature comforts, including proper beds, a/c, modern bathrooms, electricity and good food. Chalets 60 OR, tents 64 OR

samavillages.com. Newish and well-equipped camp with accommodation in a neat circle of attractive sandstone chalets and tents (all en suite) in traditional Omani style, with pretty little rug-covered verandas. It lacks some of the atmosphere of more traditional tented camps, but compensates with above-average creature comforts, including proper beds, a/c, modern bathrooms, electricity and good food. Chalets 60 OR, tents 64 OR

Wadi Bani Khalid