Valuation is a word that means a great deal to chef Linton Hopkins. He brings it up when I first meet him at a table at his Restaurant Eugene. “Compromise is dangerous,” he tells me. “You can’t turn a blind eye to things; it’s all about valuation.” When we part ways a few hours later, he calls after me: “Don’t forget. Valuation.” (My interpretation: it’s all about knowing what things are worth.)

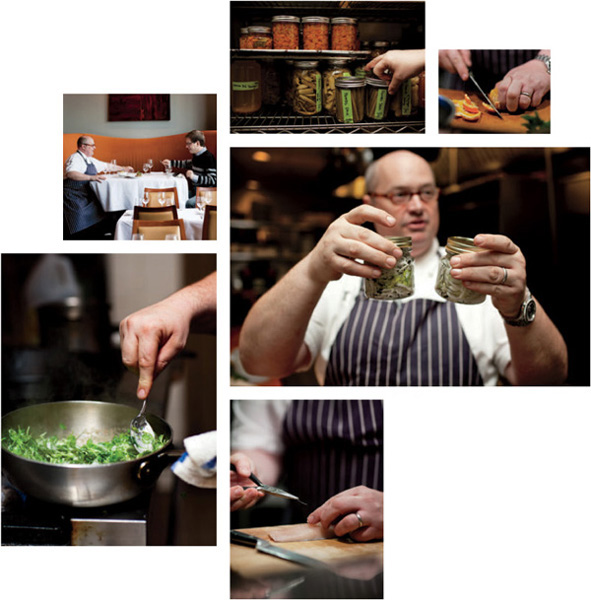

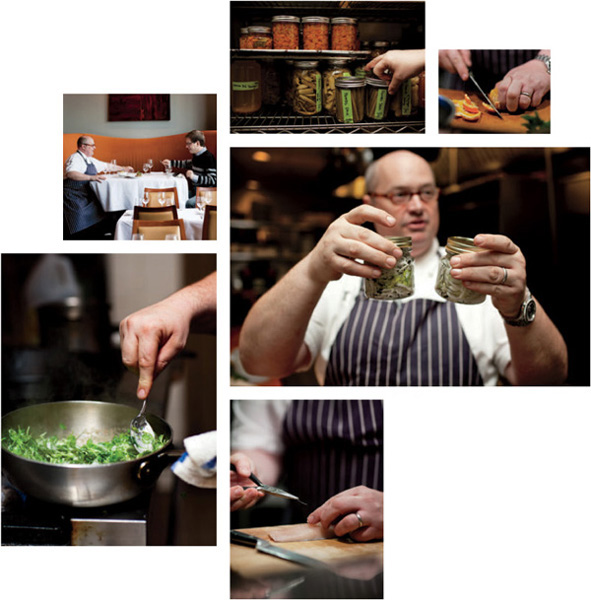

Hopkins, a round, bespectacled Southerner, is like a cross between a friendly Southern farmer and a formidable French chef. As if to confirm that latter half of his persona, he tells me that early in his career, he would have sous-chefs measure his cuts. “A julienne means one eighth of an inch by one eighth of an inch by two inches.”

The friendly-Southern-farmer part of his persona comes through in the way he holds forth on a variety of topics, including restaurant cooking versus home cooking (“At home, you have to clean everything yourself”), pickling (“I’m a big believer in preservation; I want to open a restaurant with zero refrigeration”), and taking pride in his profession (“This is a real guild; there’s a code of honor and respect”).

But it’s the subject of valuation that gets him the most worked up. “You can put lime juice and hot sauce on something crunchy and say ‘that’s good,’” he explains, “but that’s not enough.”

Learning how to value food properly requires a certain amount of discrimination. You have to notice the difference between a red radish from the supermarket and a Spanish black radish straight from the farm; you have to feel the difference between a conventional yellow onion dusty in its supermarket bin and a fresh Vidalia onion so sweet, says Hopkins, “My daughter eats them like apples, straight from the ground.”

With those two farm-fresh ingredients—the radishes and the onions—Hopkins illustrates the way that he values good food, pickling them to preserve them. “In the South,” he says, “it’s all about pickles.”

Hopkins approaches pickling with a casual enthusiasm that’s infectious. “You just sort of wing it,” he says.

On his shelves, he has kumquats pickled with garlic and chilies, and pickled fennel stalks (“They make great straws for bloody Marys”). Later, he’ll use his pickled garlic and pickled banana peppers to prepare a vibrant dish of greens. He’ll also make a seared trout with a watercress puree that doesn’t have pickles in it, but that gets a hit of acid from an orange and a lemon.

It’s valuation, though, that underscores everything that happens in Hopkins’s kitchen. At one point he opens the lid of his garbage can and asks, “What have I thrown away?” He peers inside. “The stems from those leeks.” He pauses and reflects, “I could’ve put them in a stock. I could’ve made a leek broth.”

The fact that Hopkins can muster such pathos over wasted leek greens reveals the purity of his mission, the sincerity behind his ethos—an ethos built around a simple word, but a word that matters: valuation.

“Recipes no more make a good cook than sermons make a saint.”

Makes one 8-ounce jar of pickles

This is just one example of the many things you can do if you start pickling the produce you find at the farmer’s market. Because black radishes and Vidalias were in season when I met with Hopkins, this is what we cooked together, but you don’t need to follow this recipe precisely. The important part is the ratio of vinegar to sugar to water; memorize this and you can pickle all kinds of things, from kumquats to fennel stems. This recipe is wonderful with fish or pork or, even better, mixed with mayo and spread on a sandwich. Once you start pickling, the possibilities are endless.

3 or 4 large black radishes

2 small spring Vidalia onions or an equal amount of cleaned leeks

2 cups distilled white vinegar

1 cup sugar

1 cup water

A pinch of kosher salt

Prepare a jar* by either washing it really well with soap and water and then boiling it, along with the lid, for several minutes or—an easier option—running the jar and lid through the dishwasher. The jar should be warm when you fill it.

To prepare the vegetables, use the julienne blade on a mandoline slicer and create a kind of radish-onion relish or simply slice the radishes and onions very thin into rounds and rings. Whichever method you choose, fill the jar alternating between the radishes and the onions, so you see separate layers of black and green. Pack the layers tightly.

In a pot, combine the vinegar, sugar, water, and salt and taste it for balance. (Does it need more vinegar? More sugar?) Bring to a boil over high heat and then pour over the vegetables in the jar, leaving room at the very top for a vacuum to form. Seal with the lid.

Put the jar right into the refrigerator; as it sits, it will get more and more intense. It won’t be shelf-stable*, though, and will only last a few weeks.

Serves 4

With the bright green cream sauce, the crisp seared trout, and the elegant orange salad on top, this is a restaurant-worthy dish through and through. But don’t be intimidated: it’s doable at home, too. Once you understand the components, you’ll realize how easy it is. The colors will pop, the flavors will meld, and you’ll wonder how something so impressive could be so simple to make.

FOR THE WATERCRESS PUREE

4 tablespoons (½ stick) unsalted butter

1 bay leaf

1 large leek, cleaned and cut into rings

½ cup heavy cream, plus more if necessary Kosher salt

1 head of watercress*, cleaned, roots chopped off

Juice of 1 lemon

FOR THE MANDARIN SALAD

2 small mandarin oranges, cut into supremes

¼ cup whole parsley leaves

¼ cup chopped dill

¼ fennel bulb, cored and thinly sliced

1 radish, thinly sliced

A pinch of salt

FOR THE TROUT

4 trout fillets, skin on, bones removed

Kosher salt

Canola, vegetable, or other neutral oil

To make the watercress puree, melt the butter in a pan along with the bay leaf and when the butter’s thoroughly melted, add the leeks. Cook them gently on medium-low heat for 5 minutes or so.

When the leeks are nice and soft, add the cream and season with salt. Bring the cream to a boil and remove the bay leaf*. Add the watercress and stir to coat. If it’s not coated, add more cream while the pan is still on the boil.

When the watercress has wilted slightly after just a minute or two, add the watercress and most of the liquid to a blender. Carefully blend (cover the hole in the lid with a towel) and adjust the consistency: it should be almost soupy. If it’s not, add more of the remaining liquid. Add the lemon juice, blend one more time, then taste for seasoning. Set aside.

For the mandarin salad, simply toss all the ingredients together in a large bowl, adjust for salt, and set aside.

Finally, run your finger along the length of the trout to check for bones. If you find bones, use pliers or your fingers to remove them carefully.

Season the fish on both sides with salt. Heat 2 cast-iron skillets* on high heat until very hot. Add a splash of oil and then 2 trout fillets per pan, skin side down, and press the fish into the pan with your hands or a spatula.

Cook until the trout is almost completely opaque and the skin is crisp, 3 to 4 minutes. To finish, carefully flip the fish over and cook for a few seconds on the flesh side.

Spoon the watercress puree onto 4 plates*. Top with the trout and then pile the salad over it. Serve immediately.

Serves 4

There’s so much going on in this recipe—four kinds of greens; a porky, bacon-y base; pickled garlic; chilies; and pickled chilies on top—it takes greens from black-and-white to Technicolor. Even though the elements here are specific (the tasso, the pickled banana peppers), they’re all easy to substitute. Or you can just pick and choose the elements you like. Whatever you do, there’s one thing for certain: these greens won’t be boring.

1 bunch of collard greens

1 bunch of mustard greens

1 bunch of kale

1 bunch of greens from spring Vidalias (or, alternatively, scallions)

1 tablespoon peanut oil

½ cup cubed tasso* (see Resources) or pancetta

1 onion, chopped

2 dried red chilies

2 pickled cloves garlic*, chopped

Approximately 1 cup chicken stock (enough to cover the greens)

Kosher salt

Apple cider vinegar

3 pickled banana peppers*, cut into rings

Triple-wash the greens by filling a large bowl or sink with cold water and dunking the greens in, a bunch at a time. Shake under water and then shake out of the water. All the dirt will go to the bottom of the bowl; pour the water down the sink, refill, and repeat the process 2 more times until the greens are super clean. (Nothing ruins dinner more than dirt in your greens.)

Once the greens are clean, remove the stems and give the leaves a rough chop.

In a pan large enough to hold everything, add the peanut oil and the tasso. Raise the heat to medium high and let the fat render. When the tasso is caramelized and deep golden brown, add the onions. Raise the heat a bit: you want to cook the onions aggressively for 3 to 4 minutes.

When the onions are softened, add all of the greens. You should hear a loud sizzle. Add the dried chilies and the pickled garlic. Add enough chicken stock to cover the greens and season with salt and a splash of vinegar.

Bring the mixture to a boil, lower to a simmer, and cook for 15 minutes. There should still be some liquid at the end*.

Taste the greens one last time to adjust for salt and acid. Spoon into serving bowls and top with the pickled banana peppers. Serve immediately.