Section One

COLLECTING SMITH & WESSON:

SPECIAL CONCERNS AND TRICKS OF THE TRADE

Smith & Wesson may legitimately be characterized as the premier handgun manufacturer of the United States and the world. Its rich history and wide range of products make it a fascinating study for historians and a treasure trove for collectors. It was the first American maker of repeating handguns that fire self-contained metallic cartridges, and continues as the leader in the police, civilian, military, and sporting handgun market today.

Odds are good that any shooting sportsman or general gun enthusiast will have at least one Smith & Wesson around. It would be difficult to find a gun shop anywhere that didn’t have a few S&Ws in the handgun display case. Any time a double-action revolver or semi-auto pistol purchase is planned, it’s likely that a Smith & Wesson product will at least be considered.

Accordingly, we’ve tried to make a book that will be straightforward and useful to the general dealer or gun enthusiast, as well as contain a level of detail useful to the most advanced collector. We’ll start out by discussing a few concepts that you need to grasp in order to “speak S&W.” (Hint: Check out the “Illustrated Glossary” at the end of the book if you run into confusing terminology.)

FRAME SIZES OF REVOLVERS

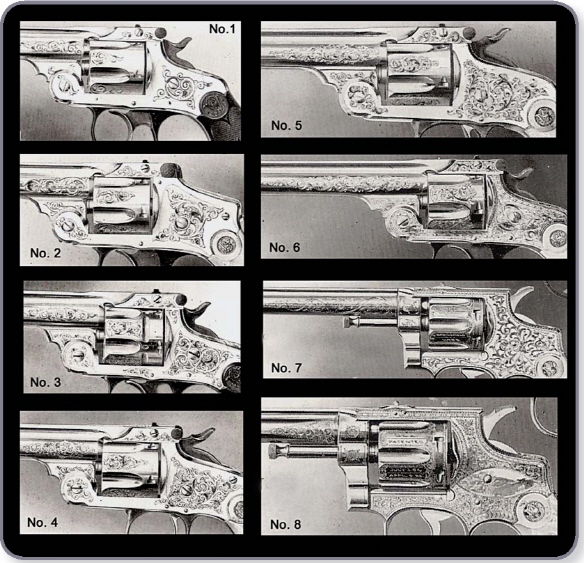

S&W revolvers are often referred to by frame sizes. On the tip-ups and top-breaks, these are numbers. On Hand Ejectors, they are letters.

Frame sizes of Tip-up (rimfire: “rf”) and Top-break (centerfire: “cf”) revolvers.

TIP-BREAK TOP-BREAK

• Model 1 frame – smallest; 7-shot .22 tip-up only

• Model 1-1/2 frame – medium small; 5-shot .32 tip-up or top-break

• Model 2 frame – medium; 6-shot .32 tip-up or 5-shot .38 top-break

• Model 3 frame – large; 6-shot .44 top-break

Frame sizes of Hand Ejectors.

HAND EJECTORS

• M frame – smallest; 7-shot old model Ladysmith only; no longer made.

• I frame – small; 6-shot .32 size; no longer made; has leaf mainspring, replaced by the improved I frame.

• Improved I frame – still a small frame but with a coil mainspring, Usually a 4 screw frame, replaced by the J frame.

• J frame – small; 5-shot .38 size; (6 in .32 caliber) current production; Chiefs Special sized. This frame was enlarged slightly in 1995 to accept the .357 Magnum round, and may be called the “J Magnum” frame. By 1997, all J-frame revolvers were produced on the J Magnum frame.

• K frame – medium; 6-shot .38 size; current production; .38 Military & Police size. Redesigned in 1999.

• L frame – medium-large; compromise between K and N size; current production, redesigned in 1999.

• N frame – large frame; 6-shot .44 size; current production; .44 Magnum size, redesigned in 1999.

• X frame – humongous frame with K-frame grip; recently introduced for the .500 Magnum.

Although the above “J, K, L, N” frame size terminology is generally used by collectors to designate both carbon steel and stainless steel revolver frame sizes, the S&W factory uses a separate set of letters to designate stainless steel frame sizes. In this system, a stainless J-sized frame is an E frame, a stainless K is an F, a stainless L is an H, and a stainless N frame is a G frame. For more information on factory frame designations, see the beginning of the “Numbered Model Revolver” section.

SCREWS: 3, 4, OR 5

S&W collectors often refer to Hand Ejector (HE) revolvers by the number of screws in the frame. From about 1905 to 1955 most Hand Ejectors had five screws – four sideplate screws and a screw in the front of the trigger guard. About 1955, the top sideplate screw was eliminated on most models, and these are referred to as four-screw guns. Around 1961, the trigger guard screw was eliminated, and all subsequent production is known as three-screw. When counting screws, remember that the rear sideplate screw is covered by some types of grips, and don’t overlook the trigger guard screw that enters from the front of the trigger guard. To confuse things further, the earliest Hand Ejectors, 1896 - 1905, had only four screws (pre-five-screw four-screws?), and some models had a sixth screw, a locking screw that held in place the top sideplate screw, found in early alloy frame revolvers.

Screw count on Hand Ejector frame.

PINNED AND RECESSED

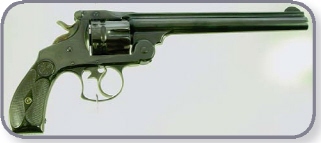

Pinned vs. non-pinned barrel.

Recessed vs. non-recessed cylinder.

This refers to Hand Ejectors made prior to about 1982. Prior to that time, all Hand Ejectors had the barrel fixed to the frame by a pin through the rear of the barrel and the frame and all magnum caliber revolvers had recessed chambers to enclose the rim of the cartridges. Rimfire .22 Long Rifle cylinders have been counterbored since 1935 and continue so to this day. When the Magnum centerfire caliber recessed cylinder was discontinued the overall length of the cylinder was changed to make up for the difference in rim thickness.

GENERATIONS OF SEMI-AUTOS

The centerfire metal frame traditional double action style semi-autos produced from 1954 to date are sometimes referred to by their generation:

First Generation: Made 1954 - 1982. Examples have two-digit model designations, most notably Model 39 and Model 59.

Second Generation: Made 1980 - 1988. Many improvements, some oriented to ensure reliable function with new styles of ammunition developed since introduction of first generation. Examples generally have three-digit model designations.

Third Generation: Made 1988 - date. Many improvements; most obvious on casual inspection are improved ergonomics of a more rounded comfortable grip. Examples usually have a four-digit model designation. (There are two notable exceptions – the “no-frills” variations of these models, which tend to have three digit model designations in the 900s; and the compact Chiefs Special versions of‚ these models which have model designations consisting of “CS” plus the caliber – i.e., “CS-40”.)

Note: Not all S&W semi-autos fit into the generation designations. Examples include the early .32 and .35 pocket semi-autos, .22 semi-autos, the polymer-framed Sigma series introduced in 1994, and the Walther design SW-99 introduced in 1999.

TYPE OF FINISH

As with all gun collectors, S&W enthusiasts invariably seek guns with original factory finish.

Generally, but not always, a blued top-break revolver will bring a bit more than a nickel gun in comparable condition. There are at least three reasons: First, for most of the 19th-century nickel was a more popular finish and in most, but not all, models was a more common finish than blue. Secondly, nickel finish is more durable than blue, so a higher proportion of surviving nickel guns will show more finish than their blued counterparts. Finally, a nickel gun that has lost a good portion of its finish can have a dark and bright mottled appearance that many collectors dislike, while a blue gun tends to have a more blended appearance to its color as it loses its finish.

As we move into the Hand Ejectors, single-shots, and semiautomatics, the situation tends to be reversed. In most, but not all, of the later models, blue was much more common than nickel and there was an additional charge for nickel plating.

Over the past two decades, stainless steel has become the overwhelming choice of revolver buyers, to the extent that some blued carbon steel models have been discontinued in favor of their stainless steel counterparts. On a S&W purchased for actual use, stainless models nearly always bring more than their blued or nickeled counterparts. Where a substantial premium is paid for a particular finish, we have tried to note it in the listing of the individual model.

Special finishes will generally bring a premium if factory original. Among tip-ups and top-breaks, silver or gold plating may occasionally be found. Among Hand Ejectors, two-tone nickel and blue finished guns, nicknamed “pintos,” could be special-ordered during certain eras.

Examples of scarce special-order “Pinto” finish.

REFINISHED GUNS

Identifying a refinished gun is very much an inexact art, but can be vitally important when considering paying a hefty premium for an antique or rare variation gun that has a high percentage of original finish. Some things to look for include:

Markings should be crisp. Edges of letters should not show drag marks or blurring. Screw holes should not be dished.

Metal edges should be sharp, not rounded. You may find it easier to check this by running a finger across the edges rather than relying on your eyes.

Inspect the finish carefully for pits or scratches under the finish that were too deep to polish out during refinishing. S&W factory polishing was nearly always excellent, with no discernable scratches or dings left on the gun before the original finish was applied. Blemishes underneath the finish suggest a refinished gun. Don’t rush – spend some time with a magnifying glass.

Compare the color, luster, and polish of the finish to known original examples.

Get enough light. Outdoor sunlight is great, but not always practical. The very powerful pocket flashlights, such as those offered by Sure-Fire, are great for closely inspecting blued finish. Gun shows tend to be held in venues with notoriously poor lighting – “sellers’ light.” A flashlight can be a great help.

Does the finish show appropriate signs of aging? Older blued guns in particular tend to slowly turn “plum,” a flat purplish-brown color that seems to emerge from underneath the brighter factory bluing. Under very strong light, this will often be discernable on old original blued guns, while more recently reblued guns may tend to show a more solid blue, with less depth. Nickel finishes, on the other hand, occasionally will turn milky. Although generally bright original nickel finish would be preferred to milky nickel, the milky effect is reportedly difficult to duplicate with artificial aging methods, and may lend some assurance that the plating is old (remembering that old doesn’t always mean original).

Is the finish correct in the markings? Generally, factory applied markings (or factory engraving for that matter) would be applied before the final finish. Accordingly, there should be original finish in these markings. Conversely, markings applied after the gun left the factory would generally be cut or stamped through the original finish.

Many cold-blue touch-up formulas have a distinctive odor that tends to linger on the gun. Don’t be shy about giving a gun the old sniff test.

Is other wear to the gun consistent with the remaining finish? A heavily-shot bore, worn action, or eroded grips should raise questions about the originality of an otherwise “minty” finish.

Check the heads of studs and pins that protrude through the frame to see if they have been polished flat or are rounded as originally made. This is an obvious clue. For example, the stud that receives the center sideplate screw on top-break revolvers is difficult to remove and is often left in the frame and polished flat when the gun is refinished. On a gun with original finish, or on most factory refinished guns, the end of this stud will be rounded and protrude slightly above the surface of the frame. Likewise, the pin that holds the front sight is sometimes left in place and polished flat during a non-factory refinish.

Look at the finish of parts that originally had a finish contrasting with the rest of the gun. For example, most pre-stainless guns had a color case-hardened trigger and hammer. Top-break revolvers often had contrasting trigger-guards – blued on a nickel gun or case-hardened on a blued gun. Latches on nickel top-breaks were often originally blued. A gun on which all parts are blued or nickel should be looked at closely for other signs of refinish.

On most blued top-breaks, it is commonly believed that the muzzle and the tops of the frame posts on either side of the latch should be polished white, and bluing on these areas suggests reblue.

Never say never. There may be exceptions to any rule.

A CONTRARIAN CAVEAT ON HIGH CONDITION GUNS

Most experts recommend buying the highest condition guns one can afford, and certainly mint guns are those that tend to bring the record prices. (Coincidentally, many of the experts are in the business of selling guns. Hmmmmm.) It is our opinion that there are restoration artists who can restore a gun so as to fool even the most expert observer. As the dollar amount realized for the highest condition guns continues to outstrip the cost of such restoration, you can’t help but wonder if at some point the market for the highest condition items will sound a retreat due to concern over this practice.

We like guns that show honest use consistent with their history. We are not entirely comfortable paying double price on an antique gun for those last few percentages of original finish. We are quite possibly in the minority in these opinions.

FACTORY REFINISH

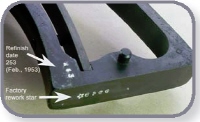

Any refinishing will generally diminish the value of a gun as compared to one with comparable original finish. However, among S&W collectors, a gun that has been refinished at the factory will bring a price somewhere between original finish and a non-factory refinish. The factory no longer refinishes older guns. Most factory refinished guns are marked in some manner to indicate the rework. Check for markings on the butt, on the rear face of the cylinder (including under the ejector star), on the bottom of the barrel, and on the grip frame under the grip panels. Markings believed to suggest a possible factory refinish include:

• Five-pointed star on the butt: Probably the best-known rework marking, this indicates the gun was returned to the factory for rework. However, the work may have been a repair other than refinishing. Use of the star declined in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

• Date on grip frame under grip panels: A three- or four-digit number indicates month and year of refinish (for example 954 would be September 1954); often found in conjunction with other markings.

• A diamond with the letter B or N (blue or nickel) or S (standard, i.e., blue): Sometimes seen as a star with an N. Sometimes marked on the rear face of the cylinder, including occasionally underneath the ejector itself. Usage of this marking believed to have followed the star on the butt. It has been suggested that a diamond refinish mark may sometimes indicates a major part replacement, such as barrel, cylinder, or frame.

Typical factory refinish marks.

• B, N or S inside of a rectangle: Usage believed to have followed diamond marking. Sometimes noted as R-S or R-N (believed to stand for refinish-standard or refinish-nickel) on the grip frame under the grip panel.

Bear in mind that some of the above markings – particularly the star by the serial number – may indicate a return to the factory for some work other than refinishing. Also note that just as original-appearing factory markings can be stamped on a gun undergoing refinish or restoration by someone other than the factory, there is nothing (other than his conscience) which would prevent someone other than the factory who had refinished the gun from applying factory-style refinish markings.

In recent years, S&W has not marked factory refinished guns in any way. For many years they have declined to refinish older and antique models.

RARE BARREL LENGTHS

Rare barrel lengths will bring premiums when confirmed by factory letter.

Cataloged barrel lengths are nominal measurements only. Actual barrel measurement may vary as much as 1/8” from that listed. Revolver barrel length is measured from the front of the cylinder to the tip of the muzzle. Semi-auto barrel length is measured from the breech face to the tip of the muzzle.

Before paying a substantial premium for an unusual barrel length, inspect it carefully for signs of being cut, stretched, or replaced.

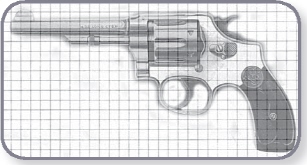

Measuring barrel lengths.

In most cases, markings on a barrel, such as S&W name and address and patent dates, are centered on the barrel in relationship to the barrel length. For example, the markings on the top of an original rare 6” American barrel will end closer to the breech end than they would on a standard 8” barrel.

Some shorter than standard barrels will have special markings in special locations, such as on the side of the barrel rather than on the top of the rib, due to lack of space for the full standard markings in the usual location.

Check to see that the barrel is both original to the gun in question (see section on matching serial numbers) and of the correct model. Many models will interchange barrels. For example, one of the authors has purchased on two different occasions what he thought was a rare 4” barreled New Model #3 only to discover the barrel was actually a common 4” barrel for the .44 DA. These would have been easy enough to detect by the lack of serial number or by the different patent dates, if only he had been a little smarter and a little slower to reach for his wallet. It is certainly possible that the factory used interchangeable model barrels rather than discard excess parts, but incorrect barrel markings will raise a red flag of caution for the careful buyer.

Look at the muzzle to see if its properly crowned, including the slight recess usually found on a barrel rib. Check the attachment and configuration of the front sight to be sure it’s factory type. Look at the finish of the barrel to see if it is consistent with the rest of the gun.

There is a restoration practice called “stretching” the barrel that has been used to restore cut barrels to their original length. Tip-offs for older stretched barrels include failure of rifling groves inside the barrel to line up perfectly and missing barrel markings. However, newer procedures consisting of relining the barrel interior and remarking the exterior are reportedly virtually undetectable to the naked eye. The problem of “messed with” barrels is not a new one. Consider this 1901 report from the Springfield Republican: “Four employees of Smith & Wesson’s shops, who were employed in boring barrels, were discharged on Thursday. It was found that when they had made a mistake and bored the barrels larger than they should be, they used a process to shrink them. This prevented their having to pay for the barrels as spoiled stock, but it turned out a bad barrel, as the bores were left at the right size at their ends, but too large in the center.”

Other Barrel Concerns: Guns which have been fired with an obstructed bore will sometime bulge the barrel. This may sometimes be visually observed as a high bright ring on the barrel or as a dark circle in the bore. Sliding the length of the barrel between thumb and forefinger will sometimes allow you to tactilely detect subtle bulges that are missed by visual inspection. Also check the rear of the barrel on revolvers for cracked or split forcing cones (often a problem on the tiny .22 Ladysmiths). Either a bulge or bad forcing cone will reduce the value of a revolver.

OTHER MODIFICATIONS AND UNUSUAL CONFIGURATIONS

The general rule is that any modification from the original configuration of the gun will adversely affect value. However, this is less true in some areas than in others.

Post-factory markings that confirm a known particular historical usage of a gun have always been an exception, and in many cases add to the value.

While condition collectors may have no interest in such items, collectors interested in the Old West may not object as strongly today as in the past to period of use modifications such as bobbed barrels or removed trigger guard spurs. A few years ago, the popular sport of cowboy action shooting, where participants assume Old West personae and compete with period firearms, had the effect of increasing the value of the S&W top-breaks in medium condition grades and provided a ready market for period altered guns that are otherwise mechanically sound. Perhaps regrettable is that many of the guns used in cowboy action shooting are refinished by their owners, which should further boost the value of original finish remaining on old S&Ws in the future.

Eye of the beholder – unusual period non-factory alterations interest some collectors, turn off others. Top to bottom: New Model #3 converted to .22 single shot; modified sights, hammer & carved ivory grips on New Model #3; Russian Model with a .22 single shot barrel added on top of the .44 revolver barrel. Supica photo.

Factory errors do occur, and will bring a premium from interested collectors. However, they can also be the product of after-factory gunsmithing or fakery. The buyer should proceed with caution.

MATCHING SERIAL NUMBERS

To bring full price, serial numbers and assembly numbers on a S&W should match:

Early production revolvers used assembly numbers to designate which parts went with which gun. On these, the serial number was marked on the butt and the right grip panel, but a separate assembly number, usually one to four characters (usually either numerals or numerals combined with letters or special characters such as “&”), was marked on the grip frame under the grip panels and on the various major parts – usually cylinder and barrel on tip-ups and cylinder, barrel, and latch on top-breaks. The barrel number on top-breaks can be tricky to find – it is usually marked in the small flat just to the right of the latch (lifting the latch while the gun is open makes it easier to see).

In the 1870s the assembly number system was replaced by using the gun’s serial number on the major component parts.

On Hand Ejectors through the late 1950s, the serial number is stamped on the frame, barrel flat, cylinder face, yoke (crane), behind the extractor star, and right grip panel, in addition to on the butt.

After about 1960, revolvers had assembly numbers stamped on the frame, sideplate, yoke, and sometimes on the cylinder under the extractor and on some small parts. After about 1988, only the frame and sideplate are marked with assembly numbers.

The effect of a mismatched number on price is variable. Probably of least concern are situations where it appears there is a transposition error in numbers. An example would be where all parts except the cylinder are marked 4567 but the cylinder is marked 4576, although admittedly this is not common. Mismatched grips are not usually a major concern unless the grips are incorrect for the model, such as the occurrence of civilian grips on a military model that should have cartouches. On top-breaks, generally a mismatched latch is of less concern than other major parts. A mismatched top-break cylinder may be somewhat acceptable, especially if it is from a close serial number or from another gun in the same known usage (for example, many Japanese military New Model #3s are found with mismatched cylinders from other Japanese military guns).

However, where a barrel and frame don’t match, or none of the parts match, there will generally be a major impact on collector value. This is especially true when guns appear to be partially a rare model or configuration and partially a common type.

SMITH & WESSON STOCKS (GRIPS)

By James G. King II (Jim King)

Smith & Wesson called them stocks. Their catalogs persistently and specifically used the term stocks instead of grips. The reasons are not known, but a guess might suppose a company desire to be technically correct and to further the Smith & Wesson image of outstanding quality. Judging from their consistency in calling them stocks for over a century, it seems clear the distinction must have been important to S&W. With respect for S&W’s century of consistency, in this chapter we will generally continue S&W’s practice of calling them stocks.

It is important to keep in mind that dates mentioned in this chapter are not set in stone, but are approximate times of transition. Production changes were not necessarily immediate or absolute. There are overlaps, fluctuations back and forth between processes, frugal use of existing parts, special orders, and shipping dates that are not necessarily correlated to dates of manufacture. Almost all dates and time periods regarding S&W production are general guides and subject to variations and exceptions. The development and evolution of stocks is subject to similar uncertainties. Dates and time periods mentioned are approximate and based on observations, literature referenced, and factory literature.

While everything printed in this chapter is believed to be accurate, there are probably errors and inaccuracies. The scarcity of published information on S&W stocks leaves much to observation and analysis. It is hoped this chapter will be of assistance to S&W collectors and will contribute to expanding the body of knowledge about S&W stocks.

S&W STOCKS BY FIREARM TYPE

The following will provide a general understanding of the stocks found on most S&W firearms. It is a general outline only. There will be many variances.

Tip-Ups

Standard stocks on all tip-up models were smooth rosewood.

S&W Tip-Up Stocks. Left to Right: Model One 1st and 2nd Issues, Square Butt; Model One 3rd Issue, Round Butt; Model Two Old Army, Square Butt; and Model One-and-a-Half 2nd Issue, Round. All photos in the grips section by Jim King.

Top-Breaks

S&W small and medium frame top-break stocks. Top Row, Left to Right: Black Hard Rubber, .38 Single Action First Model Baby Russian, with S&W block logo; and, Red Mottled Hard Rubber, .38 Double Action Second Model. Bottom Row, Left to Right: Black Hard Rubber, .32 Single Action, without S&W logo; Red Mottled Hard Rubber, .32 Single Action, with S&W block logo; Black Hard Rubber, .32 Single Action, with intertwined S&W logo; Black Hard Rubber, Floral Pattern,.32 Double Action; and Black Hard Rubber, .32 Safety Hammerless.

S&W large frame top-break stocks. Top Row: Red Mottled Hard Rubber, .44 Double Action. Bottom Row, Left to Right: Plain Walnut, American, Square Butt; Plain Walnut, Russian, Round Butt; Black Hard Rubber, New Model Number Three, Round Butt; and, Checkered Walnut, New Model Number Three, Round Butt.

Smooth walnut stocks were standard on the American, Russian, and Schofield models.

Hard rubber stocks were introduced in the late 1870s and eventually became standard on the top-break revolvers. They are the most common style of stocks on the New Model Number Three and .44 DA based models, with checkered or smooth (scarce) wooden stocks also available. Optional detachable shoulder stocks made of walnut were available on special order for the Americans, Russians, and New Model Number Three large frame topbreaks, with metal buttplate on the American &Russian shoulder stocks, and hard rubber buttplate on those for the New Model Number Three. Hard rubber stocks were fitted to nickel plated .38 Single Action First Model Baby Russians, but most of the scarce blued guns were fitted with walnut stocks.

Most hard rubber stocks had molded checkering with the familiar intertwined S&W logo in the stock circle at the top of the panels. Some exceptions were the early .32 centerfire single action stocks which first had no logo, followed be a block letter logo, and finally the intertwined S&W logo. Another exception was the Baby Russian, whose stocks had a block letter S&W logo in the stock circles.

Unusual hard rubber stock variations, worth a premium, include the rather striking red mottled stocks. This red/black combination was standard on the .320 Revolving Rifles (1879 - 1887), both for stocks and forearms, although for some unexplained reason, the forearms always seem to be more brightly colored than the stocks. Red mottled stocks may also be found on all frame sizes produced in the era from about 1879 to about 1882. Blue and green mottled variations have been reported.

An entirely different variation of hard rubber stocks, quite scarce, is found on some .32 Double Action Second Models. Called the floral, peacock, or wild turkey stocks, these have a molded floral pattern rather than checkering, with a bird that could be either a turkey or peacock lurking in the design.

Single Shots

S&W Single Shot Stocks. Left to Right: Black Hard Rubber Target Stocks; Walnut Target Stocks, with gold medallions; and, Plain Walnut Straightline.

The First Model Single Shot (Model of 1891) pistols and combinations sets were typically fitted with hard rubber target stocks on their round butt frames. Plain and checkered walnut and fancy stocks of ivory and pearl were available on order. The Second Model .22 Single Shot had hard rubber target stocks as standard. The Third Model .22 Single Shot introduced in 1909 was typically fitted with checkered walnut target stocks, initially with gold plated medallions, but after about 1917 - 1920, without medallions. The Fourth Model .22 Single Shot (Straight Line) had plain walnut panels with gold plated brass medallions.

Early Hand Ejectors (1896 - 1950)

S&W Small Frame Hand Ejector Stocks. Top Row, Left to Right: Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, Regulation Police Extension Stocks, Pre-World War II (pre-war); and, Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, Regulation Police Extension Stocks, Post-World War II (post-war). Note variation in checking patterns. Bottom Row, Left to Right: Black Hard Rubber, Ladysmith 1st and 2nd Models, Round Butt; Plain Rosewood, 3rd Model Ladysmith, Square Butt; Black Hard Rubber, .32 Hand Ejector, Round Butt; Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, I Frame, Round Butt, pre-war; and, Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, I Frame, Round Butt, post-war.

S&W K Frame Hand Ejector Stocks. Although not pictured, N Frame stocks demonstrate the same variations, with the exceptions that hard rubber was not used and round butt frames were not available on production N Frames. Top Row, Left to Right: Black Hard Rubber, Round Butt, used 1899 to about 1940; Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, Round Butt, with silver medallions, post-war, used 1946 to about 1950. Bottom Row, Left to Right: Walnut, Square Butt, flattened top without medallions, used about 1904 to about 1910; Walnut, Square Butt, with recessed gold medallions, used about 1910 to about 1920; Walnut, Square Butt, round top without medallions, used about 1920 to about 1929; and, Walnut, Square Butt, with flush silver medallions, used about 1929 to about 1941.

S&W K Frame Hand Ejector Stocks, Inside Panel View. Although not pictured, N Frame stocks demonstrate the same variations, with the exceptions that hard rubber was not used and round butt frames were not available on production N Frames. Top: Walnut, Round Butt, with concavely rounded silver medallion, post-war. Left to Right: Black Hard Rubber, Round Butt; Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, Square Butt, with gold medallion; Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, Square Butt, no medallion; and, Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, Square Butt, with flush silver medallion.

Hard rubber was also the standard stock material used on early I-frame round butt Hand Ejectors from 1896 until about 1940, although checkered walnut also came into common use in the 1930s and was the standard on the .22/32 Kit Guns. Hard rubber was also used for oversized target stocks for the I frames, but was generally replaced by checkered walnut after about 1920. The Regulation Police style “stepped” grip frame was almost always fitted with checkered walnut extension stocks.

While hard rubber was the early standard on round butt K frames, checkered walnut stocks were also fitted. The square butt K frames introduced about 1904 and the N frames introduced about 1907 were fitted with checkered walnut stocks as the standard.

Hand Ejector stocks evolved through a series of progressions that produced numerous variations in stock circles, medallions, checkering patterns, stock circle inserts, screws and escutcheons, and general configurations. The following will describe the major changes.

Until about 1910 wood stocks had a flattened or slightly convex area at the top of the stock panels in an area called the stock circle. Around 1910, (earlier for I frames, later for N frames) recessed, gold plated brass medallions bearing the intertwined S&W logo were added to Hand Ejector stocks. A small medallion, about four tenths of an inch in diameter, was used on I frame stocks. A larger medallion, about a half-inch in diameter was used on K and N frame stocks.

When WWI interrupted commercial production, the 1917 Army revolvers were fitted with plain walnut stocks without medallions, the earliest ones having the flattened tops and later ones having plain concavely rounded stock circles. Beginning in 1917 (with overlap to perhaps 1920), the medallions were eliminated and the stock circles became plain and concavely rounded, like the later version of 1917 Army stocks.

About 1929, flush chrome plated brass medallions bearing the S&W intertwined logo began to appear in the stock circles. The small medallions, about four tenths of an inch in diameter, were used on both I and K frame stocks. The large medallions, about a half-inch in diameter, were used in the N-frame stocks, although some K-frame stocks also used them.

In 1932 the Wesson Grip Adapter was introduced for N frames, with the K frame version becoming available in 1934. The adapter consisted of two blued steel plates which fit between the stock panels and the grip frame, secured by an extra long stock screw provided with the adapter. The plates had forward extensions which held a rubber filler piece between them with a screw so that it filled the area below the frame between the trigger guard and the grip frame. The filler piece positioned the shooting hand lower on the grip frame so that the trigger finger was more in line with the trigger, and it provided a surface for supporting some of the revolver’s weight on the middle finger. The filler piece had been promoted by Walter Roper as an aid to target shooting and was usually incorporated into his custom stock designs, later to become a standard design component of virtually all target stocks for revolvers.

Another type of grip adapter consists of a metallic or synthetic rubber filler piece that extends downward along the front strap to provide a larger, more comfortable grip for most shooters. This type of grip adapter is secured to the front strap by a thin metal strip bent around the strap. When the stocks are installed over the metal strip, they generally do not fit snugly due to the thickness of the strip. For this reason, it is fairly common to encounter stocks that have been altered by removing enough wood from each panel to allow them to fit snugly over the strip. This type of adapter became available around WWII and was made by Pachmayr and others. S&W produced its own version in about the 1950s. They were used on many, if not most, police revolvers prior to the popularity of replacement rubber grips such as Pachmayr’s.

S&W K Frame Magna Stocks. Top: Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, Round Butt, post-war, used about 1950 to about 1967. Bottom Row, Left to Right: Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, Square Butt, prewar, used about 1936 to about 1946; Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, Square Butt, post-war, used 1946 to about 1952, Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, Square Butt, post-war, used about 1953 to about 1967; Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, Square Butt, Plain Clothes, post-war, used 1952 to about 1967; Checkered Walnut, Square Butt, used about 1967 to about 2000.

S&W K Frame Magna Stocks, Inside Panel View. Counterclockwise from screwdriver tip: Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, Square Butt, pre-war, with unmarked in-the-white machined steel stock circle insert, reported to be early production; Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, Square Butt, pre-war, in-the-white machined steel stock circle insert stamped with patent marking, reported to be later production; Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, Square Butt, with blued machined steel stock circle insert, very early postwar, used 1946; Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, Square Butt, with blued stamped steel stock circle insert riveted by concavely round medallions, early post-war, used 1946; Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, Square Butt, with blued stamped steel stock circle insert, without relief hole for domed-head rear sideplate screw (which was replaced by a flat-head screw), post-war, used about 1946 to 1973; Checkered Walnut, Square Butt, with stamped stainless steel stock circle insert, used about 1970 to about the early 1990s.

In 1935 Magna style stocks were introduced as an option for the .357 Registered Magnum and other N frames. In 1936, Magna stocks became available for the K frames. Magna stocks cover the grip frame like standard stocks, leaving front and rear straps exposed, but have a “horn” on each panel that comes up on the side of the frame along the backstrap, providing a wider surface to spread the force of recoil at the web of the hand between thumb and forefinger. After WWII, Magna stocks became the standard for Hand Ejectors.

During WWII, the Victory Model stocks were plain walnut without medallions, and concavely rounded plain stock circles. The stock screw thread was changed to a standard thread about 1944 during wartime production. The earliest .38 M&Ps shipped after WWII were fitted with leftover plain walnut Victory stocks fitted with pre-WWII style flush chrome plated medallions.

Beginning in 1946, several significant changes to stock design were introduced, made possible by new machinery at the factory. The chrome plated silver medallions were changed from flush to having a rounded surface to match the contour of the stock wood. The checkering was modified from the prewar standard 16 lines per inch to 14 lines per inch, with rounded instead of sharp corners and a different border for the checkered area. The stock circle insert was changed from a machined steel disk to a stamped, cup-shaped, blued steel disk.

From the beginning of the use of checkering on S&W stocks, including the hard rubber stocks, a diamond-shaped area around the escutcheon and escutcheon nut was uncheckered. Stocks having this checkering pattern are often called “diamond checkered stocks” or “diamond stocks.” This nomenclature is somewhat awkward and causes confusion because every point in the checkering is diamond-shaped due to the angled lines cut by the checkering process, causing many to believe that all checkered S&W stocks are diamond “something.” The term “diamond center” is also used and seems likely to be the most clearly descriptive of the names. The diamond center description will be utilized in this chapter. The diamond center checkering pattern was eliminated about 1967-1968.

Modern Hand Ejectors (1950 to Date)

By about 1950, Magna stocks were standard on all Hand Ejectors. Perhaps due to a worldwide shortage of precious metals following WWII and continuing into the Korean War (or Conflict, depending on how the political hairs are split), the chrome plated brass medallions were replaced with molded silvery-gray plastic medallions complete with intertwined S&W logo. Plastic medallions were used until about 1952 when they were replaced with steel medallions. By about 1953, the use of plated brass medallions had resumed. In 1952, the Plain Clothes (PC) style square butt Magna stocks were developed with a rounded bottom and more rounded front shoulder on the horn. The slimmer, more rounded shoulder on the front of the horn would soon become the standard, replacing the sharp shoulder configuration of the horn which had been used since the introduction of Magna stocks.

About 1967 - 1968 the uncheckered diamond center around the escutcheon and nut were eliminated on all checkered wood stocks. About 1973 the escutcheon and nut that had been used since introduction of hard rubber stocks in the late 1870s were changed. The hollow-round, silver-colored style which was installed with the edges flush with the stock surface was replaced with a flat, recessed, brass style which would be used until S&W’s factory wood stocks were discontinued in the 1990s. About this same time, the stock circle insert was changed from blued steel to stainless steel as standard for all revolver stocks, although the stainless steel version had been in use on stocks for stainless steel guns since the early 1960s.

S&W Plain Target Stocks. Left to Right: Early Smooth Rosewood “Coke Bottle,” Square Butt, without extractor relief cut, used early 1950s; Smooth Goncalo alves, Square Butt, with extractor relief cut, used about 1967 to about 1980; Smooth Rosewood, Square Butt, with speed loader cut, without stock circle insert, used about 1970s to early 1990s.

S&W Diamond Center Checkered Target Stocks. Left to Right: Early Diamond Center Checkered Walnut, Square Butt, without extractor relief cutout, used early 1950s; Diamond Center Checkered Goncalo Alves “Coke Bottle,” Square Butt, with extractor relief cut, used about 1955 to about 1968; Diamond Center Checkered Goncalo alves, Square Butt, with extractor relief cut, used about mid-1950s to about 1967.

S&W Checkered Target Stocks. Left to Right: Goncalo alves Checkered Target Stocks with extractor relief cut, dated 1978; Goncalo alves Checkered Target Stocks, with speed loader cut, dated 1981; and, Resin Impregnated Laminated Birch Checkered Target Stocks, with speed loader cut, from the early 1990s. Note the distance separating the medallions from the checkered panels. The close spacing on the right panel is typical of late stocks made without stock circle inserts.

Target stocks that covered the front strap and extended up over the gun’s frame between the trigger guard and knuckle were introduced for the K frames in 1950, followed be the N frames by 1952, and apparently a little later for the J frames. The earliest target stocks did not have a relief cut at the top of the left panel behind the cylinder. Their full contour made extraction of spent cartridges somewhat difficult, with used stocks often wearing dents from the cartridge rims in this area. By the mid to late 1950s, an extractor relief cut had been added to the left panel to solve this difficulty. By the mid 1970s (early 1980s for N frames) a larger speed loader cut was incorporated to allow speed loader use with target stocks. The changes in checkering pattern, escutcheons, nuts, and stock circle inserts on target stocks paralleled the Magna stock changes outlined above. In the 1980s, the stock circle inserts were eliminated entirely and replaced with a rounded boss in the wood which fit against the gun’s frame. On this style of target stock, the medallions were secured by riveting the end of the post against the stock wood.

One variation of target stocks draws special interest from collectors. “Coke bottle stocks” were introduced for K and N frame target revolvers in the mid 1950s. These very desirable stocks were made in both plain and diamond center checkered versions. (Checkered versions are scarce in K frame. Beware of altered N frame stocks represented as original K frame.) Rosewood is the most common material, but Goncalo Alves and to a lesser extent, walnut, were also used. The diamond center checkered version was standard on early .44 Magnums and is fairly common on early Model 57s, but could be ordered on other models, or purchased as an accessory. The Coke bottle name reportedly comes from the shape of the stocks when viewed from the rear. The resemblance to a Coke bottle requires some imagination, but there is a little swell in the middle around the screw and a little flare at the butt. On early examples, the filler piece is generally larger than on most other target stocks, giving them a distinct shape. On the more common diamond center checkered version, the checkered area is larger than on other S&W target stocks, providing a distinct appearance. With their unique shapes and beautiful woods, the Coke bottle target stocks are perhaps the most visually striking of all S&W wood stocks.

The J-frame revolvers are the smaller, lighter frame size which is often chosen for everyday and concealed carry. Since size matters, the J-frame revolvers have usually been offered with tiny wood “splinter” or “sliver” stocks so as to minimize their size. The Centennial and Bodyguard models have special Magna stocks called “high horn” stocks with enlarged horns that come up higher on the sides of the frame. Custom stock maker Craig Spegel developed a custom boot grip designed to provide a larger, more secure gripping surface without substantially increasing the gun’s bulk. Variations of boot grips by Hogue, Eagle, Uncle Mike’s, Ace Grip Co., Altamont Grips, and others have been used as standard on modern S&W revolvers, especially short-barrel J frames.

By about 1975 Goncalo Alves became the standard wood for oversized target stocks for all frame sizes. Target stocks also became standard on many large frame guns. Traditional wood stocks were largely discontinued in favor of synthetic and laminated wood stocks in the 1990s.

The round butt configuration for revolvers has proven popular due to versatility related to its smaller nominal size. While it readily fits the smaller hand, a change of grips can adjust the grip size to custom fit a larger hand, or convert it to square butt grip configuration. Accordingly, S&W has phased out square butt guns in favor of a product line featuring all round butt revolvers.

There is an interesting cycle here which has repeated twice over 150 years of revolver production. All the earliest tip-ups had square butt grip frames, but by 1868, all except the No. 2 Old Army had been changed to round butt. Americans, 1st Model Russians, and Schofields had square butts, but their successors, the New Model Number Threes, had round butts. The round butt was standard on all S&Ws by 1878. By 1891, hard rubber extension stocks had become available for the single shots and combination sets to convert the round butt to square butt configuration for target shooting. With the introduction of the square butt on the .38 and .32/20 M&P Models of 1902, First Change in 1904 (the square butt configuration was called the Model of 1905 by S&W to distinguish it from the earlier round butt configuration), the square butt began to make a comeback. With the ever-present possible exception of a special order, all N frames since 1907 were square butt. In 1917, the Regulation Police stepped grip frame and extension stocks were introduced to provide a square butt configuration for certain I frames. By WWII, square butts dominated the K frames and round butts were scarce except on the small frame revolvers. After WWII, round butt guns continued in production, but were vastly outnumbered by square butts. Recently, after nearly 100 years of producing mostly square butt revolvers, S&W has again reverted back to round butt as the standard, with the square butt configuration available by installing conversion stocks when desired.

Semi-Auto Pistols

S&W Automatic Pistol Stocks. Left to Right: Walnut Checkered Panel for Model 39; Rosewood Plain Panel for Model 39; Rosewood Checkered Panel for Model 39; and, Walnut Checkered Panel for Model 41.

S&W Automatic Pistol Stocks. Left to Right: Xenoy Wraparound Grip used on 2nd and 3rd Generation Pistols; Red Nylon Panel for Model 46; High Impact Plastic Panel for Model 845; and, Synthetic Wood Panel for Model 422.

Beginning with the .35 Semi-Automatic Pistol in 1913 and continuing with the .32 Semi Auto, the Models 39, 41, 46, and 52, S&W fitted its semi-auto pistols with walnut (and occasionally fancy wood) stock panels. Beginning with the Model 59 in 1971, the trend has been toward more durable synthetic materials. There have been exceptions, as wood panels were tried on some second-generation guns, but the very thin wood panels tended to split under recoil. Third-generation centerfire semi-autos are made exclusively with one-piece wraparound synthetic Xenoy grips, which play a large part in their improved handling characteristics. For most third generation models, replacement Xenoy grips can be had from S&W with either straight or curved backstraps to fit the shooter’s preference. Some recent variations include various inserts which can be changed to adjust the size of the curved backstrap.

Long Guns

The stocks and forearm of the .320 Revolving Rifle were red mottled rubber while the detachable buttstock was walnut with a hard rubber butt plate bearing the S&W logo, and blued or nickel plated steel attachment hardware with a mounting point for the tang sight. Sporting Rifles were typically fitted with American walnut stocks. S&W shotguns were usually fitted with American walnut stocks on sporting models, and wood or synthetic stocks on law enforcement versions.

FACTORY STOCK NUMBERING

From the beginning of commercial production and continuing up to the mid to late 1970s, S&W stocks were “numbered” to the gun to which they were originally fitted. The gun’s serial number was marked on the inside of the right stock panel (the one on the right when the gun is upright with the muzzle pointing straight away). The serial number marking did not include any prefix, which could be a letter or numbers and a letter, except for some Victory Model stocks which did include the letter prefix.

From the Model 1, beginning in 1857, wooden stocks were usually marked by individually stamping the digits of the serial number. Black hard rubber stocks were introduced on the Model 1-1/2 Centerfire in about 1878 and received the same stamping treatment. Sometime before 1900, the stamping method of marking was replaced with pencil numbering on wood stocks and scratched numbering on hard rubber stocks. About the time when silver medallions were added to wooden stocks around 1929, stamping again became the standard method of numbering stocks to guns. Around the mid-1960s, the stamping was changed from individually stamped digits to a straight line stamping near the bottom of the right panel. The practice of numbering stocks was discontinued in the mid to late1970s when production methods developed tolerances sufficiently close to allow stock installation on guns without individual fitting.

CONDITION AND PRICE GUIDELINES FOR S&W STOCKS

Evaluating Condition of S&W Stocks

To effectively use the price guide for stocks, it is important to understand the definitions of the terms used to describe condition. The following condition grades are based on the amount of wear and damage, factory defects, and the presence of repairs or alterations. The condition grades presented here have been developed for stocks suitable for collector grade guns, where condition is usually important. These terms are specifically developed for use in grading S&W stocks and do not apply to guns or other items.

NEW: New stocks are in the same condition as when they left the factory. Other equivalent terms are Mint, Perfect, or 100%. This means no scratches or rubs on the finish, no dents on sharp edges or anywhere else, no damage to sharp corners or the tips of the horns, no distortion to the grip pin holes from installation on a gun, no broken points on checkering, and no damage to the screw head. This also means no factory defects, which are not uncommon on S&W stocks.

EXCELLENT: Excellent means nearly new, except with no more than two minor defects or spots of damage. Minor defects and spots of damage are: scratches no more than one half inch in length on the surface of, but not through, the finish; rubs or very minor surface abrasions on the finish not more than one quarter inch in the longest dimension; small dents less than one eighth inch in the longest dimension which are not obvious, but apparent on close examination; no more than two broken points in any one location in the checkering; tiny splinters of wood no more than three sixteenths inch in the longest dimension missing on any sharp corner or sharp edge; no more than one small factory defect such as uneven sanding, tiny chip removed prior to finishing, medallion not seated perfectly flush, medallion slightly rotated, or stock circle insert poorly riveted; or, grip pin holes slightly enlarged from installation on a gun. Excellent grips are not perfect, but it takes close examination to see the defects. Excellent condition grips are good enough to put on a 99% gun.

GOOD: Good stocks show minor honest wear. Minor honest wear means: tips of diamonds in checkering are flattened by light wear; no more than 10 checkering points broken in any one place with no more that two such damaged areas; noticeable small dents up to one quarter inch in the longest dimension, but no gouges where wood is missing; scratches up to one inch in length may be through the finish, but no patches of finish missing; factory defects which are obvious such as rotated medallions, medallions protruding significantly above the wood surface, minor chips removed before the finish was applied, or badly riveted stock circle inserts; or, minor chips up to one quarter inch in the longest dimension which do not detract from overall good appearance. Good condition stocks include those that would otherwise qualify as excellent except for a repair or refinish which is only apparent on close examination. Good condition stocks are good enough to put on a 90% gun.

FAIR: Fair condition stocks show substantial wear and tear. Signs of substantial wear and tear include: almost all points of checkering are worn smooth on the tips, and areas of checkering no larger than one inch in the longest dimension may be worn smooth; more than six significant scratches through the finish; dents larger than one quarter inch in the longest dimension which are easily noticeable without close examination; patches of finish missing up to one inch in the longest dimension; chips up to three eighths inch in the longest dimension; repairs to escutcheon or nut, grip pin holes, medallions, or stock circle inserts; minor cracks up to one inch in length; obvious, but correctly done refinish; or; very minor sanding of bottom edges to remove small chips or dents. Fair condition stocks may include Good or Excellent condition stocks that are missing parts that can be easily replaced or excellent condition stocks that can be salvaged by a quality refinish. Fair condition stocks are good enough to put on an 80% gun.

POOR: Poor condition stocks are generally not suited for collector interest except as examples of rare variations or to install on rare guns in poor condition. Poor condition means: worn out, badly damaged, or abused; checkering worn off in areas larger than one inch in the longest dimension; obvious chips; deep scratches into the wood; large areas of finish missing; gouges where wood has been removed; altered, carved, or sanded; poorly refinished; or missing parts such as escutcheons, medallions or stock circle inserts. Poor condition stocks are generally not good enough to put on a collectible gun, but may be useful on a working gun or a shooter.

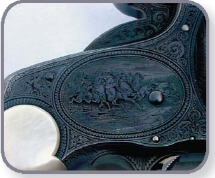

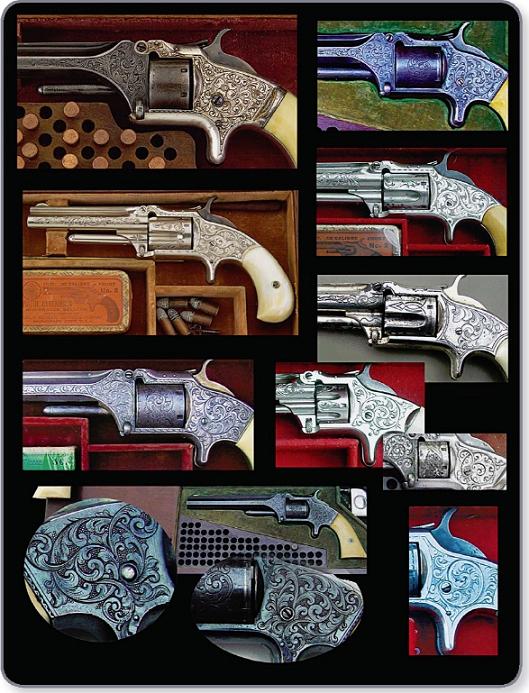

Fancy Stocks

Fancy stocks of pearl, ivory, stag, exotic wood, or other material were available both from the factory on order and from non-factory aftermarket suppliers. Aftermarket suppliers continue to produce fancy stocks today. Beginning about 1893, factory-produced pearl and ivory stocks had small round S&W medallions inlaid, to distinguish them from non-factory stocks. Revolver boxes from this era may be found with a flyer glued on the bottom inside urging buyers to insist on genuine S&W stocks with the medallions. Pearl stocks with gold medallions in excellent condition may be worth $150 to $300 or more depending on model and frame size. Factory pearl stocks without medallions in excellent condition may be worth $50 to $100 depending on frame size.

Period pearl or ivory stocks will usually bring a premium on antique S&Ws. Exceptions would include rare variations that had a unique stock, such as military guns with inspector cartouches on the wooden panels, or a special order gun missing its special order fancy stocks. In the 1800s, pearl was considered the more deluxe and desirable stock material, resulting in more pearl stocks sold than ivory. The result is that ivory stocks are scarcer and will bring higher market prices from collectors today. Genuine S&W fancy stocks are generally worth more than aftermarket stocks.

Pearl and ivory stocks may be found decorated by checkering, inscription, or relief carving. Pearl grips were more difficult to work due to their brittleness and the toxicity or the dust created. To minimize these hazards, pearl was reportedly worked under water in a water bath. Decorated exotic stocks tend to bring an additional premium due to the additional craftsmanship of the decoration. An excellent set of old ivory stocks with high relief carving for a large-frame single-action may be worth $1000 or more by themselves without a gun to wear them.

Aftermarket ivories will usually bring a premium, if genuine ivory and not a modern synthetic imitation (sometimes made with ivory dust imbedded in polymer). Ivory stocks will tend to mellow with age, the grain may become more pronounced and slight crazing or cracking may appear. Pearl may also tend to yellow slightly. The aged appearance of yellowing (and minor cracking on ivory) will generally not detract from value if consistent with the age and condition of the gun, and may actually enhance value by providing a visual appearance that gun and stocks are of the same vintage. An aged appearance can be artificially created, however. See the discussions of pearl and ivory stocks in the stock materials section for information on evaluating authenticity.

Custom Target Stocks. Left to Right: Griffin &Howe Checkered Walnut Custom Target Stocks, with Roper-style checkering pattern; Cloyce Checkered Walnut Custom Target Stocks; and, King Gun Sight Company Checkered Walnut Right Hand Thumbrest Custom Target Stocks.

Custom Target Stocks. Left to Right: Roper Checkered Walnut Custom Target Stocks; Roper Checkered Walnut Custom Target Stocks; and, Lew Sanderson Checkered Walnut Custom Target Stocks.

Custom wooden stocks by noted makers may bring a premium or be collectible on their own. Custom target stocks by Roper, Kearsarge, King Gun Sight Company, and Griffin &Howe attract considerable collector interest. Other custom stocks by lesser-known makers like Herrett, Cloyce, Fitz, and Fuzzy Farrant are not easily identified or well known and fail to draw much notice. Mass production wood stocks by Herrett, Sile, Mustang, Eagle, and others, along with synthetics by Franzite, Jay Scott, Rugged Products, Tyler Tru-Fit, Fitz, and numerous other makers will usually reduce a gun’s value. Whether aftermarket or incorrect era factory replacements will enhance or detract from gun value will depend on the desirability of the stocks on their own, whether they are correct for the period, their condition, and the scarcity and cost of the standard stocks that should have been on the gun.

General Price Guidelines

As a general guideline, a pair of regular production stocks should be worth about ten percent of the value of the gun for which they were produced. However, there are many exceptions.

The most common stocks for guns produced in large quantities will not normally fetch such prices. For example, J and K frame round butt checkered walnut Magnas and K-frame square butt walnut checkered Magnas are quite common and will bring five to seven percent of the value of a common gun in like condition. Synthetic stocks for semi-auto pistols may not draw buyer interest when priced at $10 or less. In contrast, pre-pg014- WWII K and N frame Magnas in excellent condition from the late 1930s may equal or exceed the value of the more common guns of that era.

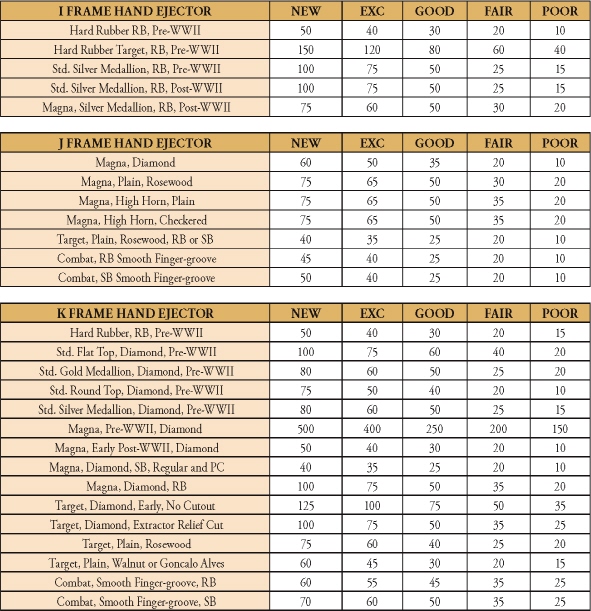

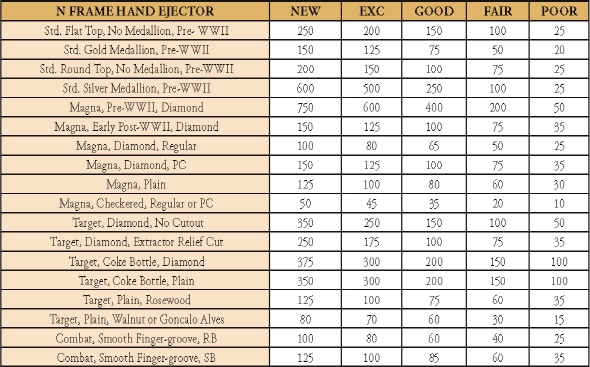

The stock value tables in this section provide estimated values for regular production stocks that exceed the ten percent guideline or have significant collector interest. The tables do not include fancy stocks, stocks for antiques, semi-auto stocks, aftermarket stocks, or common stocks with minimal collector interest whose value is consistent with the ten percent guideline. Values are based on recent sales transactions.

In the stock value tables, the word “diamond” is substituted for “diamond center” and indicates checkering around a diamond-shaped uncheckered area around the escutcheon and nut. “Checkered” means checkered without a diamond-shaped uncheckered area around the escutcheon and nut, while “plain” means smooth, without checkering. “RB” means round butt and “SB” means square butt. Other terms and materials are discussed elsewhere in this chapter and in the Illustrated Glossary and Index.

STOCK PRICE GUIDE TABLES

References

Jinks, Roy G., Personal Communication, 2005

Neal, Robert J. and Jinks, Roy G., Smith & Wesson 1857-1945, Revised Edition, R & R Books, Livonia, NY, 1996.

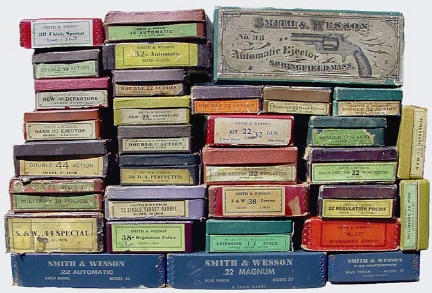

S&W boxes. Old Town Station Dispatch photo.

A BRIEF CHRONOLOGY OF BOXES &ACCESSORIES

by Dave Ballantyne and Dick Burg

Boxes and their contents (cleaning and sight adjustment tools, instruction papers, wrapping, etc.) are not a universally accepted subset of S&W collecting. Some collectors have no interest at all while others see it as an integral and valuable addition to the gun itself. Perhaps part of this is due to the challenge involved, as the survival rate of such ephemera is generally lower, much lower, than that of the guns themselves.

Many of the boxes found with handguns today are not original to the gun. Large numbers of them have been separately collected from online auctions, gun shows or even yard sales and mated to the gun with the specific intention of increasing the guns value or desirability. The authors take no position on boxes but would caution collectors that purchasing a box for $X does not necessarily increase the value of your prized gun by an equal amount. In general, having the truly original box increases the value more.

As with all things relating to collecting firearms, condition and rarity will be the determining factors for pricing boxes. It’s impossible here for us to give definitive prices for all the variations that exist. However rare boxes can fetch enormous prices. In at least one exceptional instance over $4000 was paid to purchase a numbered box in order to reunite it with the original gun. As with any purchase, learn as much as you can about your subject before you buy – check out what similar items sell for on the internet sites, talk to those more knowledgeable on online forums or at gun shows. As a very rough guide we offer the following based on observations of the 2006 market:

• Blue boxes from the 60s/70s should sell for around $20

• Gold boxes vary greatly on the model but in general $50 - $75 is a reasonable for a good condition example. K-22s, .357 Magnums and others are $125 and up

• Labeled two-piece maroon boxes from $50 to many hundreds; very model dependent

• Display or patent boxes from $150 upwards, depending on the model

• Picture boxes (red or blue) generally begin at $300; the sky’s the limit here....

At time of writing S&W has been making firearms for some 154 years. During that time it has used many containers for its products, some of them for many years and some for only a few months. As most collectors know, S&W has always been a frugal and prudent manufacturer and discontinued older parts have often found themselves being utilized when urgently needed on the production line. The same is true of spare boxes.

For example, if S&W had none of the correct boxes in stock they would use what they did have until stock was obtained. In evidence of this there are numerous examples of guns shipped in “unusual” boxes, properly labeled but in the wrong style or color. On other occasions S&W would continue to use up stock long after standards had been altered. As an example of this situation consider the infamous gold boxes with embossed blue model specific lids. These were introduced after WWII and phased into use on a model by model basis from 1946 onwards. They were mostly phased out again from the mid-late 1950s when stocks began to run down. S&W continued to use them for certain slow selling models such as the K-32 until the mid 1960s, long after similar gold boxes for faster selling models had been phased out.

For the reasons stated the authors offer the dates below purely as a timeline guide for the S&W collector, not as “hard” information. There will be variations on a model by model basis and, as with everything else about collecting S&Ws, there are always exceptions to the rules.

IMPORTANT NOTE: Many of the dates given overlap – this is correct and intentional.

BOXES

1852 – 1900: Cases

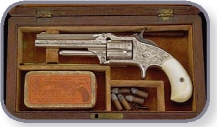

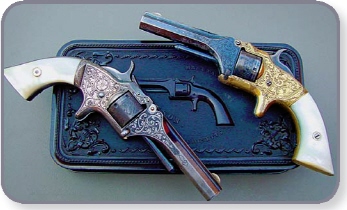

Special permanent cases for the storage of side arms, especially fancy or presentation arms, were popular during the second half of the 19th century. In general these were special order items or were added by the distributor after shipment from the factory.

Gutta percha cases for Model Ones. Photos by Jamie Supica.

Model One 1st and 2nd Issues are sometimes found with “gutta-percha” or shellac type cases and are generally considered to be correct for these models. These types of case are discussed further in the section on Tip-Up Revolvers. Both wooden and leather-covered wooden cases have been found for most tip-up and single action top-break revolvers.

The only wooden case of that period that was actually manufactured by S&W was for the Model 1-1/2 Single Action Centerfire, aka the .32 Single Action. This particular case is tri-sectioned on the interior and has a gold-embossed black “Directions for Use” label glued inside the lid.

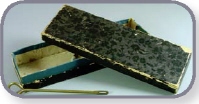

M.W. Robinson style wooden case. Photo courtesy of David Carroll.

Other standard wooden cases were offered by the larger distributors such as M.W. Robinson and have come to be considered as “factory” by collectors. A particular style considered to be an “M.W. Robinson” style case has a hinged wooden lid that fits over a raised wooden inner lip on the bottom portion of the case. The interior is partitioned, with a large area for the gun with a notched brace piece under the barrel, and two smaller compartments, the larger of which is usually sized to fit a box of cartridges. The interior is lined with fabric of various colors. A key to identifying this type of case is to look at the bottom, which was made out of a lower quality “box wood” than the well finished sides & lids. Relined cases can often be identified by the lack of wear & stains on the fabric lining. Double casings are especially prized by collectors, particularly in those rare situations where two different models were cased together (often a holster pistol with a smaller pocket pistol).

AUCTION BLOCK

Double cased pair – No. 2 Army & Model 1-1/2 New Model cased together, “factory wood case… very fine…85% (M.2)…90-93% (M1-1/2)” - $24,150 - Amoskeag, Garbrecht collection, Sept. 2005.

Double cased pair – 1st Model Russian, 98%, with Model 1-1/2, 99%, both ivory stocked, “dealer cased” – $28,750 – same auction.

Wooden cases were especially popular in England and France. While features vary, some characteristics typical of many British casings include oak exterior, often with a brass or other metal oval inlay in the lid for the owner’s monogram; fabric lined partitioned interior; and frequently a dealer’s or arms maker’s paper label on the interior of the lid. Instead of partitioned interiors, “French-fitted” cases have interiors with cutouts exactly fit to the contour of the gun and other accessories.

Special cases were still used well through the turn of the 20th century, observed more often with top-break revolvers than with Hand Ejectors. As time moved on, leather lined exteriors gained in popularity. The factory offered a special casing for its “combination sets,” each set consisting of a 38 SA 3rd Model revolver (Model 1891) with one or more single shot barrels and accessories – usually an extra set of grips, screwdriver and cleaning rod. Two types are known, one with an oak exterior and the other a Moroccan leather exterior. Both were chamois lined. A similar type casing was offered for pairs of single shot pistols. Either is quite rare.

Cleverly made reproductions of period cases have been in circulation for many years. Differentiating between the original and the reproduction is an arcane art mastered by relatively few collectors. Some pretty spectacular and convincing looking “special casings” have been fabricated out of legitimately old jewelry boxes and silverware cases.

Wooden cases for special individual guns or for special models have remained available, both through S&W and aftermarket suppliers, to the present day.

Early Two-Piece Cardboard Boxes: 1852 - 1880s

Throughout most of S&W’s history, the majority of guns have been shipped in cardboard boxes.

Early Two Piece Cardboard Boxes: It is believed that the earliest S&Ws were shipped in mottled two-piece blue, green, or black cardboard boxes.

Original boxes for Model One & Model Two. Model Three box (bottom) may be a later than period-of-manufacture factory repair return box. Old Town Station Dispatch photo.

Some original cardboard boxes for the Model 1 and Model 2 have been observed as two-piece, covererd with black texture patterned fabric. Different patterns have been observed on the exterior, and the upper lip of the bottom part of the box is seen lined with light blue paper. Others are observed with various colors of mottled exteriors. It is believed these boxes had neither interior nor exterior labels. They are quite rare, and one in nice condition has been known to sell for thousands of dollars.

Original box for Model One.

It is unknown what boxes were used for the earliest Model Threes. An American has been observed in a two piece unlabeled maroon box, but it is believed that was likely an early factory return box, used to ship the gun back to its owner after an early factory rework, later than the period of manufacture.

Late 1870s - Early 20th Century: Hinged Lid Boxes

The hinged lid cardboard boxes consist of fabric covered cardboard with the lid connected to the box. Many of these boxes survive with fabric tape hinges intact, perhaps surprisingly, although the corners often suffer from insufficient support and are prone to tearing.

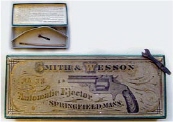

Original Baby Russian box, with combination tool. Old Town Station Dispatch photo.

This appears to have been first used on the 38 SA 1st Model “Baby Russian,” which has the only “picture box” from this era. The green box has a fancy paper label on the lid with a picture of the gun and gold highlight (which fade rapidly), with cardboard partitions on the inside. The 38 SA 2nd Model and the .32 SA had similar green boxes, with the .38 SA having an oval top exterior label. These boxes also probably introduced the interior lid “Directions for Use” informational labels, which continued for a long time in S&W cardboard boxes.

.32 & .38 Double Action and Safety Hammerless boxes. Unattributed photos in the box section are from ArmsBid.com.

From about 1880 S&W began to use a wide variety of colors including black, brown, maroon, mustard, blue, and red. Presumably the colors were originally used to differentiate models in some way but this knowledge has been lost to us over the years, although many theories have been put forward. Many .32 and .38 DAs are observed in brown hinged lid boxes, with many Safety Hammerless models showing up in mustard boxes for .32 cal. and red or maroon for .38. The 3rd Model Single Shot is found in a lavender colored box. Reddish-brown seems to be the most common color for early Hand Ejector hinged lid boxes.

Late Model Three boxes. Supica collection.

The New Model Number Three and .44 DA families of models may be found with these hinged lid boxes. Green has been observed for the New Model No. Three, brown for the .44 DA Models (with an additional “Frontier Model” end label on the lid for that variation), and dark blue for a New Model No. Three Target Model. These boxes are rather scarce, and it would be difficult to draw hard and fast conclusions from the number observed. Oddly, the most commonly found box for the Model 3 family is the green box for the scarce extension shoulder stocks for the New Model No. Three. It seems a stash of these shoulder stocks still in the original boxes turned up several decades ago.

Early hinged-lid Hand Ejector boxes.

Also around 1880 S&W began to use end labels to describe the contents of each box. Initially this was used on the Double Action models. A green label generally designated a blued gun, with nickel guns packed in boxes with orange or white end labels. The serial number is usually marked in pencil or grease pencil on the bottom of the box.

Beginning Late 1920s:

The Patent or Display Box

Patent boxes.

Around the end of the 1920s S&W introduced a new type of hinged box with the hinge attached to the bottom edge of lower portion of the box rather than the top edge. The front edge of the box itself was beveled to allow the box lid to close flush, and the box could be opened displaying the contents and thus the name “Display.” Because the S&W patent for this design is marked inside these boxes, they are sometimes alternatively known as “Patent” boxes. Both names are correct in the authors’ opinion. The serial number of the gun is generally written in grease pencil on the bottom of the box.

Blue picture box.

1933 - 1941 – Blue Picture Box. In early 1933 S&W introduced a blue box with a picture of the model printed on the lid and with model information printed on the sides on the lid. It is believed that these were initially issued for both the 38/44 Heavy Duty and Outdoorsman models. This same style of box was also used for all the pre-WWII .357 Magnum revolvers (both Registered and Non-Registered). The boxes were two-piece and originally very dark blue in color. Over the years much of the color has faded, probably through exposure to sunlight, and many variations of blue coloring are now found. The interiors of the box were red in color. The corners of both bottom and lid were reinforced with matching blue metal strips. From this time on all S&W two-piece boxes had these metal reinforced corners. Production of these boxes ended with S&W’s closure for wartime production in 1941 but there are recorded instances of a few being used to ship firearms immediately after the war ended in 1946 and one as late as 1951. The serial number of the gun is generally written in grease pencil on a piece of white tape stuck on the bottom of the box.

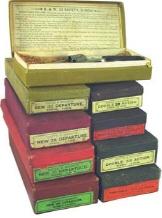

K-22 boxes, including red picture boxes. Photos courtesy of Dick Burg.

1933 - 1941 - Red Picture Boxes: These were introduced for the K-22 series Outdoorsman revolvers, possibly before the blue picture boxes. Identical to their blue counterparts these were two-piece red boxes with the model picture printed on the lid and red metal reinforced corners. The sides and ends of the lid also had the model clearly printed on them. All exterior printing was in black or gold. The interiors were also red. The 2nd Model K-22 is a prized example of this box today. The serial number of the gun is generally written in grease pencil on a piece of white tape stuck on the bottom of the box.

1946 - 1954 – Red Picture Boxes: These were used for I-frame revolvers immediately after WWII. When the J frame was introduced in 1950, in the form of the Chiefs Special model, this too went into a red Picture Box. They follow the same pattern as the other picture boxes but have silver metal corners. The serial number of the gun is generally written in grease pencil on a piece of white tape stuck on the bottom of the box.

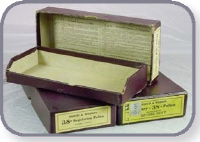

Two-piece Hand Ejector boxes.

Two-piece red kit gun box.

1946 - 1975 – Two-Piece Boxes: Following WWII, S&W adopted one of the most recognized styles of two-piece boxes. Perhaps finding the previously used hinged lids too expensive or too delicate, this style used a rigid detachable lid, which fit over the bottom portion of the box. In addition, both bottom and lid were covered with a tape-like material that provided additional support to the corners of the box. These boxes are often found with post war N frame revolvers, although medium framed guns with longer barrels have also been recorded. Early ones were sometimes maroon in color, sometimes black. Later ones were more often blue. The early maroon or black boxes had nothing printed on them but would be labeled at the factory when shipped with a gun. Many maroon boxes were used immediately after S&W resumed production following WWII in 1946. Most of the larger N-frame revolvers were shipped in these boxes until the late ‘50s, the only exceptions being those models for which gold boxes were specifically manufactured such as the 1950 Army or the .357 Magnum. The later blue boxes were often used in the ‘60s and ‘70s as shipping boxes for guns repaired at the factory or those N-frame guns sent out with wooden presentation cases. The serial number of the gun is generally written in grease pencil on the bottom of the box.

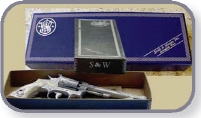

Gold picture boxes. Photos courtesy of Dan Tanko & Old Town Station Dispatch.

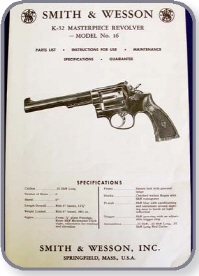

1946 - 1965 – Gold Boxes: These were introduced immediately after WWII for some models and gradually spread across most of the S&W product range. They were phased out again in the mid- and late 1950s but were still used until this date on some models. They are, perhaps, the most readily identifiable and collected S&W box. They had the specific model embossed (not merely printed) onto the box lid. The sides and ends were printed with the S&W logo and model information including the guns finish (blue or nickel) and barrel length. The metal corners of both lid and bottom have been found in blue, silver and gold. We have seen it reported elsewhere that the metal corners are coded to the blue or nickel finish of the gun but this is not correct as we have examples of both blue and nickel finished guns in boxes with all three colors. Some guns which it was not planned, at least initially, to manufacture in large numbers did not have their own gold boxes. Instead S&W merely printed a label and stuck it on the end of a suitable box identifying it. An example of this often seen is a K-38 masterpiece box housing a 4” Combat Masterpiece – the box end was labeled, as it was originally printed “6-INCH BARREL.” For gold boxes the serial number of the gun is generally written in grease pencil on the bottom of the box.

Starburst box. Photo courtesy of Dan Tanko.