TWO

The Foundation of Home Ownership

The firmest foundation for home improvement is home ownership. It is almost always the owner who improves or maintains a house, not the tenant, and owners maintain to higher standards when they also live there. It’s human nature. The landlord thinks of her property as an investment, and maintains it no better than she must, but owner-occupiers have an emotional stake too, and may fret about how they appear to friends and neighbors. They often improve the appearance and livability of their homes, well beyond what makes sense in narrowly economic terms. Then, too, if they invest their own labor they can limit out-of-pocket expenses to bare essentials.

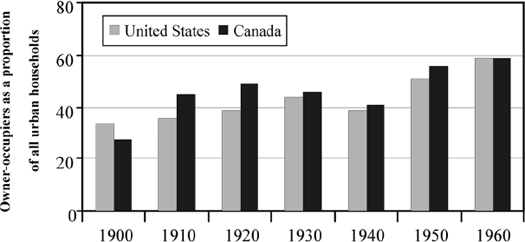

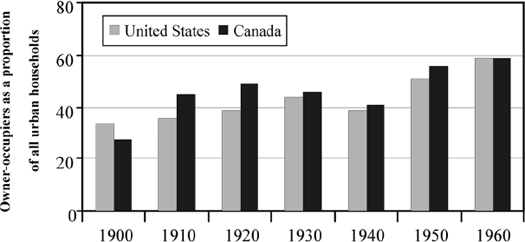

In North America in the first half of the twentieth century, the rise of a home improvement industry depended on home ownership becoming a social norm, and in two senses. First, it became common. In 1900, in the United States only about one-third of all urban households owned their own homes; the proportion in Canada was slightly lower (figure 2). In both countries, the proportion then rose irregularly, reaching about 45 percent by 1930, falling during the Depression, but rebounding to reach 59 percent in both countries by 1960. The rise of owner-occupancy and improvement did not move in lockstep. Things are never that simple: as I will show in chapter 7, the Depression actually gave improvement a boost. But in the long run, the association was strong and the cumulative effect telling.1

The growth of home ownership, and its Depression stumble, reflected trends in the standard of living. But, again, causal influences were not that simple. Today, most North Americans assume that home ownership is desirable, and have bought as soon as, and whenever, they could. This was not always so. To be sure, for decades immigrants and manual workers made huge sacrifices to put down roots in the New World. But for many decades, white-collar workers and professionals were largely indifferent to the matter. Although the fact is not widely appreciated, during the 1910s middle-class attitudes began to change. This shift in attitudes helped sustain the growth in home ownership and, with it, of home improvement.

2. The irregular growth of urban home-ownership in North America, 1900–1960. Owner-occupiers are keener on improvement than landlords or tenants, and so the rise of home improvement depended on the growth of homeownership. Compiled from Censuses of Canada and the United States.

Immigrant Passions: Shacks and Shantytowns

In the early twentieth century, the passion for home ownership and improvement was most apparent among manual workers and immigrants, not the middle class. For immigrants, above all, ownership was a mark of achievement, rescuing tenants from the landlord’s whim and, in an era before pensions and unemployment insurance, insulating workers’ families from the vagaries of the job market and old age. Nothing dramatizes their desire to own, and to improve, property more effectively than the fact that so many were willing to acquire lots and build homes, literally with their own hands. In and around some cities—including Los Angeles, Chicago, Detroit, and Toronto, Ontario—owner-building was very common. In the Toronto area, for example, between one-third and two-fifths of all single-family houses erected during the boom of 1900–1912 were built by owners for their own use, typically with their own hands.2

Toronto’s experience was unusual, but owner-building was everywhere common. Although it was not fashionable as the prime subject of contemporary accounts, it often appeared in asides. The best-known managerial experiment of the era was Frederick Taylor’s development of time and motion research. His classic study, published in 1911, was of the laborer “Schmidt,” the immigrant Henry Noll, whom he timed shoveling coal. Taylor chose him because “I knew he was building a house and that he needed money.” He reported that Noll was “engaged in putting up the walls of a little house . . . in the morning before starting to work and at night after leaving [work],” which makes his feats of shoveling even more prodigious. Another inadvertent account of owner-building was provided a decade later by a student of Ernest Burgess, a leader in the influential Chicago school of urban sociology. This student compiled life histories of young men who lived at the Hyde Park YMCA. One man from St. Paul, Minnesota, described how his parents had bought and improved his childhood home. “My father,” he told the student, “has done much of the building himself” while “my mother deserves much honor as well.” He explained that “she even did labor not customary for a woman to do, but,” he concluded, “it was all for the good of the home.”3

One reason why contemporaries often overlooked owner-building is that it happened in places removed from their experience: alleys, unfashionable suburbs, and small towns. In the late nineteenth century shacks, singly or in small communities, were tucked away on many back alleys. In 1909 Charles Weller, the executive officer of the Associated Charities of Washington, D.C., suggested that, along with tenements, shanties were how low-income families—our “neglected neighbors”—found a home. He commented that “a new crop of shacks will ripen and need to be harvested every year.” The metaphor is revealing: like other reformers, Weller was keen to rid the city of this unwelcome growth. By then, owner-builders were being displaced to the suburbs.4

Indeed workers, including many immigrants, were being pulled into the suburbs in various ways. Manufacturing was moving out, and workers followed to where land was cheap. By the 1920s, professional builders were finding it less profitable to erect workers’ dwellings, but for a time many workers manage to house themselves. In 1926, the planner A. G. Dalzell noted that “shack-towns” fringed most Canadian cities. A year later, an American planner, Jacob Crane, commented that the presence of “shacks” had “greatly agitated many suburban towns.” Unusually, Crane defended the owner-built dwelling on the grounds that it was soon improved. The more conventional view was expressed two years later by Robert Whitten and Thomas Adams. Their national survey of building inspectors had found that the majority of new single-family homes cost less than $4,200 and that in that price range “most houses are built by the owners for their own use.” This might mean that owners became their own general contractors and hired out the work. But “often,” Whitten and Adams claimed, the houses were “temporary in character or only partially completed,” lacking “modern conveniences” such as plumbing, electricity, or street improvements. Like most observers, they assumed that this situation was regrettable.5

In a few areas, suburban owner-built homes were erected by racialized minorities, including Mexicans and African-Americans. Indeed, before World War II a minority of African-Americans made their way into the suburbs in this way. A fine example was documented in 1931, when President Hoover assembled experts for a national housing conference. A subcommittee on Negro housing provided a vivid story from Nashville. An African-American had bought a lot, intending to “put up two little rooms and a shed on the back of the lot and then build the house I wanted in the front as I got the money.” But he bought more lumber than he needed, on credit, and so began building the larger house immediately. He then ran out of money and had to wait six months. He eventually moved his family in before installing windows or doors, though he did soon make a front door. In the end, continuing to improve the house, he claimed that he would not sell it for less than $6,500, though this figure may well have been unrealistic. In the southwest, some fringe areas were first settled by Mexican owner-builders. Although the fact has been largely forgotten, some of Phoenix’s early fringe areas began as Mexican cotton camps.6

But the great majority of owner-builders were whites. In 1920, for example, Kenneth Crone noted that around Montreal “in thousands of instances” the suburban lot owner “builds his house with his own hands, scrappily, with such new and second-hand material as he can pick up when he has a little loose change.” Owner-building was most common in the smaller urban centers of the western and midwestern states. In their classic study of Middletown, U.S.A. (Muncie, Indiana), the Lynds refer to the local “shedtown,” a shack community of destitute families, but most owner-built homes were more substantial while, as Jacob Crane claimed and as the Nashville story illustrates, they were commonly improved. A typical small-town experience was reported in the American Lumberman, the leading trade journal for retail lumber dealers. In 1920, a truck driver in Lombard, Illinois, bought a lot and built a 14’ × 18’ garage. He married, and the couple moved in with his brother for a year in order to save. He divided the garage into two rooms, laid pipes to the street, wired for electricity, and moved in just before his wife gave birth. Inspired by plan books from the local lumber dealer, and with a construction mortgage from the same source, he then began a five-room house on an adjacent lot. The couple completed the ground floor, and moved in just before their second child arrived. Here, for many, was a real alternative to the formal housing market.7

Some lumber dealers had always cooperated with amateurs by erecting what became known as shell houses. These were basic dwellings that owners finished themselves, though the line between “finish” and “improve” was fine. In 1926, the American Lumberman told its readers about W. W. Walls & Co., a retailer in Champaign, Illinois, that also built homes. Sometimes they erected only a frame, leaving the buyer to install plumbing, wiring, and a heating system. It was a matter of what buyers could afford. In Fresno, California, Joe King saw things the same way. At a meeting of large home builders in 1925, King reported how he turned a profit by catering to scores of workers with very modest incomes. He described how he built four-room shells on cedar posts, finishing the exterior only. Inside there was studding but no partitions, or plumbing. Typically, claimed King, the owner would “have a party,” when friends and neighbors would help finish the house. Some party! A canny lumber dealer provided credit, on the condition that buyers purchased all their materials from him.8

King was an operator. He explained how he sold Fresno residents building lots in Florida by going house to house. Even so, he supposed that the cheap methods of construction that worked in balmy Fresno could not be transferred to the midwest. In fact, B. E. Taylor, a real estate speculator, was proving that it could. As Carolyn Loeb has shown, in June 1921 Taylor began to buy up and subdivide land in Brightmoor, beyond Detroit’s city limits. Taylor was willing to sell unimproved lots: after all, he purchased tracts for $1,000 an acre and then proceeded to advertise building lots (ranging from 30’ × 100’ to 34’ × 125’) for the same price. This was good business, and he sold hundreds of lots to workers who then built for themselves. But he was also willing to build and then sell, which he also did by the hundreds. His houses were invariably modest, sometimes in the extreme. Loeb illustrates Taylor’s “model 614”—this was not a segment of the market where romantic imagery mattered—which consisted of a 440-square-foot, four-room frame structure, with no bathroom, balanced on cedar posts. But it did have a small porch and outdoor privy, which is what his customers, who were recent migrants from Appalachia, would have expected.9

In some ways, making a house became easier after 1900. Builders, and suppliers, were willing to meet the amateur halfway. New, cheap, and easily worked materials, including tin roof sheeting, tar paper, and stovepipes, were becoming more readily available. By the 1920s, however, owner-building was going into a period of decline. The evidence is scattered and contradictory. While Robert Whitten and Thomas Adams believed that owner-building was still common in the late 1920s, John Gries saw it very differently. Indeed, speaking about the very cheapest of owner-built dwellings, he claimed that “the construction of shacks or other forms of cheap temporary dwellings has practically ceased.” The truth surely lay in between. In 1932 Ernest Fisher and Raymond Smith surveyed the trend of land subdivision and development around Grand Rapids, Michigan, since 1900. In two of the four “outlying” areas they studied, they found some “shanty town” districts that lacked services. A similar process of building and remodeling was found in a study of exurban Massachusetts. Owner-builders, then, remained active, but by the late 1920s they had been displaced ever further from the city core, into exurban areas beyond the view of many housing experts such as John Gries.10

To the extent that owner-building remained an option, it gave some flexibility to the housing market’s growing reliance on filtering as the mechanism for housing lower-income households. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, builders and investors were still willing to erect homes for low-income, or at least moderate-income, households. By the 1920s, this was no longer true. More and more families were forced to occupy homes built for their social betters, which had become affordable only after they had deteriorated, and perhaps been subdivided. By the late 1930s, this process had come to be known by the term we use today: “filtering.” In the 1920s, there was no recognized term, but the process was becoming familiar. Robert and Helen Lynd offered an early description: “In each new generation,” they observed, “the less well-to-do tend to inherit the aging houses of the group slightly ‘better off.’”11

In the first three decades of the twentieth century, owner-building in urban fringe areas was put onto the defensive by the elaboration and extension of building regulations. The main impetus came from urban fires. Fire regulations inhibited the construction of cheap, flammable housing. In many cities they began to bite in the 1860s. Their introduction, enforcement, and extension varied widely, as did the extent and timing of their effects. In Toronto, for example, a big fire in 1904 persuaded the city to tighten up its regulations. This forced owner-builders to move beyond the city limits while forcing commercial builders to erect dwellings that many workers could not afford. The effect was compounded after 1913 by the city’s decision to pass a law that compelled all property owners to connect to public water and sewer lines, and to install basic sanitary services. The latter requirement was unusual in the U.S., or indeed elsewhere in Canada, but everywhere standards were being raised. It is possible to debate whether regulation was a good thing. Reformers and municipal officials claimed that it eliminated some slums and improved public health. No doubt they were right. At the same time it raised costs. Gail Radford suggests that plumbing and central heating systems—of the sort that B. E. Taylor did not provide—accounted for about one-quarter of housing costs in this period. Such averages disguise the effect on the bottom end of the market. In Toronto in the decade after the 1913 law, the cost of improving dwellings that lacked sanitary services ranged between 17 and 40 percent of the total value of these properties. Regulation reduced the construction of housing for workers by the building industry, and helped increase the significance of the filtering process as the mechanism by which housing was delivered to the poor.12

The introduction of building regulations in cities was one of the main reasons owner-building was displaced into the suburbs, and then beyond. In 1898 a writer in the New England Magazine had noted the fact that fire regulations were confined to cities while “flimsy” and “dangerous” frame construction was permitted, if only by default, in the suburbs. For the next half century well-informed observers continued to explain the presence of suburban or exurban owner-building primarily in the same way. In 1911, for example, a writer for American City, the main journal for city administrators, commented that “some of you will recall points of contact with your city where there is as much need for a strong governmental control as in the crowded conditions of your central city.” As urban growth increasingly spilled beyond city limits, the challenge grew. In 1920 the Senate Committee on Reconstruction and Production highlighted the inadequacy and inconsistency of building codes across the country, especially in suburban areas. On its recommendation, the Bureau of Standards established a Division of Building and Housing, with which a Building Code Committee was formed in May 1921. The following year the committee published guidelines that were designed to promote the standardization of building requirements and their geographical extension into unregulated territory. For a decade the committee, and indeed the whole division, was very active. In 1931 it provided “much of the staff” for the Conference on Home Building and Home Ownership that President Hoover had established in August of 1931 and which met in Washington from December 2 through 5. The following year the committee published revised building guidelines.13 But the Depression took its toll. In 1933 the division was “skeletonized . . . for reasons of economy,” and a year later it was shut down.14

Despite, and then in the absence of, the efforts of the Commerce Department, many suburban and fringe areas remained unregulated, with predictable consequences. In her anatomization of urban slums in the mid-1930s, for example, Edith Wood attributed the existence of the suburban shantytown to the fact that “no building code or health ordinance exists to hamper them.” A Canadian survey found exactly the same thing north of the border, and also targeted the lack of public controls. A decade later Richard Ratcliff deplored “peripheral shack towns” as “one of the most serious menaces to our cities,” and he explained that “building permits are not always required and few housing codes are in force.” Of course many suburbs did introduce regulations, sometimes because of concerns about fire risk and health and often in an attempt to attract affluent buyers by, in effect, excluding the poor. Around Toronto, for example, the first suburb to bring in building regulations was Forest Hill as part of its successful attempt to become an exclusive enclave. Other examples on a larger scale were Scarsdale, New York, and Palos Verdes Estates, in the Los Angeles area. In places like these, building controls were one of several tactics, including large-lot zoning and racial covenants, that served the purpose of social exclusion. The growth of these types of well-regulated suburbs attracted a good deal of attention at the time and formed a significant part of the social geography of emerging metropolitan regions. Their effect was to confine suburban owner-building to unregulated areas and to displace it into the further urban periphery.15

The Indifferent Middle Class

As a strategy for acquiring a home, owner-building was largely confined to workers and immigrants, but many writers have suggested that the desire to own was felt by everyone.16 In 1968, for example, the Kerner Commission claimed that “the ambition to own one’s own home is shared by virtually all Americans,” adding an endorsement: “we believe it is in the interests of the nation to permit all who share such a goal to realize it.” The merits of ownership have often been asserted in ways that brook no dissent. Thus Walt Whitman in the 1840s: “A man is not a whole or complete man unless he owns a house and the ground it stands on.” Or Herbert Hoover, as commerce secretary in 1923: “The love of home”—and Hoover means to include the desire to own—“is one of the finest instincts and the greatest inspirations of our people.” Or the expert conference on the subject that Hoover convened after becoming president: home ownership is an American “birthright.” By stringing together such quotations we can create the impression that the urge to own is ubiquitous and immutable. In this manner Constance Perin, in an anthropological study undertaken in the 1970s, suggests that the high social value her respondents gave to property ownership merely continued a tradition.17

Even skeptics, such as those who have promoted the idea of public housing, have been drawn into the boosterish mindset. When the U.S. Housing Authority was established in the late 1930s, President Roosevelt appointed Nathan Straus as its administrator. Appropriately, Straus believed in public housing and, more generally, in a rental sector that met the needs of Americans who could not afford to buy a home or who were so mobile that renting made more sense. Nonetheless, he believed that “throughout the ages man has dreamed of a roof, four walls, and a plot of ground that he could call his very own.” Straus, and generations of policy makers and housing administrators, assumed that home ownership was the prevailing ideal, even if reality called for compromise. For this reason, introducing a recent collection of papers on the history of federal housing policy, John Bauman can speak of “the nation’s historical commitment to the sanctity of private property and the goal of homeownership.” Since the 1930s, the federal government has indeed assumed the desire and defended the “birthright” of every American to own their own home.18

In fact, as Richard Dennis has put it, “there was nothing ‘natural’ about home ownership.” It has been desired in different degrees, for varied reasons, by diverse groups. Historians agree that the desire to own property was stronger among workers, and strongest of all among immigrants. Contemporaries knew, and indeed documented, this fact. In the early 1930s, for example, a large survey of people who were employed on federal work projects in Philadelphia found striking differences. Among this admittedly atypical group of households, 25 percent owned (or were buying) their own homes, but the percentage was higher among foreign-born whites (36 percent) than among the native-born (12 percent), and negligible among African-Americans (2 percent). Immigrants valued ownership more, and in a particular way: as security, and as a supplemental source of income.19

The flip side was that ownership aspirations were weaker among white-collar workers. Speaking about the late nineteenth century, Michael Katz and his associates have claimed that middle-class women aspired to be managers, not homemakers: having servants was more important than owning the home. The silences in household management books, which were directed at middle-class women, support this view. Their authors ignore issues associated with property ownership: maintenance, repairs, home improvement, or the merits of owning versus renting. This is notably true of Beecher and Stowe’s influential The American Woman’s Home (1870). To a modern reader, such silences are astonishing. But if we look across the Atlantic we should not be surprised. In Britain, the middle classes did not care much about owning their home. In his study of Cardiff, for example, Martin Daunton comments that “so far as the well-off were concerned, home ownership was not considered socially necessary, the general attitude being that house purchase for self-occupation was merely another investment and not of any pressing importance.” Richard Dennis has observed that, in London, suburban guides spoke of rents, not prices, and that for the middle class “place mattered more than tenure.” As a result, only about 10 percent of urban households in England and Wales owned their own homes, fewer in Scotland. In nineteenth-century Britain, workers could not afford to buy while the middle class did not particularly care to. In North America, workers had better prospects of ownership, but middle-class attitudes to property paralleled, where they did not follow, British precedent.20

By the early twentieth century, assumptions were changing. Housing tenure was becoming a question, though ownership was still not necessarily the answer. North American advice manuals began to raise the issue, in a neutral way. In The Modern Household (1912), Marion Talbot and Sophonisba Breckenridge expressed a studied neutrality about the merits of owning versus renting, or for that matter of houses versus apartments. An owned house, they note, may have some advantages but it brings “uncertain costs of operating” and a “greater amount of servicing.”21 Indeed, by the 1910s many writers were prepared to make bolder, less balanced, claims. These have to be parsed carefully. In Successful Houses and How to Build Them (1912), Charles White reeled off a list of advantages to property ownership, including control, security, status, promotion of thrift, better maintenance, and citizenship. But he was preaching to the converted: those who purchased his book would already have been more than half convinced that building and owning was a good idea. Moreover, White’s reasoning is very different from what we would expect today. He speaks of the possibility of building houses in order to rent them out. He was also undecided about whether home ownership was a good investment. Indeed, in a book published two years later by the Ladies Home Journal, he conceded that “$3,000 invested in business might yield more profit in dollars and cents than the same sum invested in a home.” His immediate point was that the best reasons for owning were nonmonetary. The larger implication is that, for the middle class, the logic of ownership was still not compelling. And so, as late as 1915, Edward Devine could sketch a “normal” middle-class home life and still make no mention of owning property.22

In fact, according to Margaret Marsh, even by World War I “home ownership did not appear to be of primary interest” to the middle class. Reformers fretted about the moral and physical threats posed by poor sanitation, overcrowding, and the taking-in of lodgers, but expressed only moderate interest in working-class home ownership. This created tensions. In Chicago, settlement workers pushed for higher building standards but they ran up against what Jane Addams called “sordid and ignorant” immigrant landlords who subdivided their properties to supplement meager incomes. In Toronto, reformers deplored the suburban shacks that immigrants built. In both cities, they believed that workers should not sacrifice health and privacy on the altar of property ownership.23

For themselves, the middle class cared about signaling social status but not, before 1914, about owner-occupation. In Philadelphia, the “city of homes,” Marsh found only middling rates of home ownership among families that could easily have afforded to buy. She cites Americus Under-down, scion of a prosperous haberdashery concern, who did indeed own a house in the district of Haddonfield. But he rented it out, while occupying a similar, rental property in the same area. The same patterns existed in Wissahickon Heights and Chestnut Hill. In Chicago, Margaret Garb has detected an “indifference” of the middle class to home ownership, which is why prosperous suburbs such as Union Park could contain large numbers of tenants intermingled with owners, while LeeAnn Lands has found the same pattern in Atlanta. Speaking of the middle class, she judges that “buying was simply not that important to most families.” The corollary was that the level of home ownership was no guide to neighborhood quality. She concludes, “Americans needed to be persuaded of the ‘value’ of homeownership and the single family home.”24 No group knew this better than builders, brokers, and indeed anyone associated with the real estate business. That is why, between about 1914 and the Depression, they launched a series of campaigns to promote home ownership as a social norm.

Buy Your Own Home. Please!

Janet Hutchison has suggested that World War I marked “a major change in housing policy for the state,” one that “provided a touchstone for the 1920s housing programs.” She understates the point: until the 1910s, there was no federal policy with respect to housing. Then, a policy emerged out of campaigns for home ownership that brought real estate interests and the state together in an unprecedented way.25

The first initiative was taken by real estate brokers, or realtors, as those associated with the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB) styled themselves in 1916 in their efforts to present themselves as professionals. The first local campaign may have dated from 1914, and by 1917 a campaign in Rochester, New York, gained national attention and was inspiring imitators. By 1918, the New York Times spoke of a “movement” of “considerable proportions” in the western states that “had even reached New York.” The key initiative was organized by Paul Murphy in Portland, Oregon, becoming the template for an Own Your Own Home (OYOH) movement. Murphy had helped develop “one of the finest subdivisions” in the Portland area. Under his guidance, and the chairmanship of the mayor, those associated with the local building industry, including brokers, lumbermen, furniture dealers, organized labor, and public service corporations, combined to mount a vigorous campaign. They built and equipped a model bungalow where a chosen couple exchanged marriage vows after hearing a sermon on the “merits of the ‘Own Your Own Home’ Movement.”26

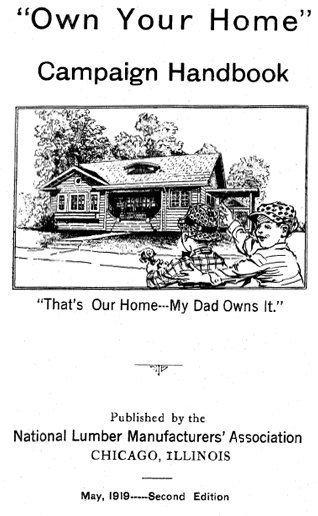

In 1918, the initiative shifted to the federal government. The War Industries Board designated house building as nonessential; promotional efforts were suspended. Exceptions were made for industrial centers with munitions factories and shipyards, where some housing was built by a new, but short-lived, federal agency, the U.S. Housing Corporation. In addition, realtors helped the USHC set up a Real Estate Division to make loans for the private construction of houses for war workers. Not surprisingly, the USHC “cooperated” in the OYOH campaigns of 1917. At war’s end, federal involvement grew. On January 1, 1919, the Labor Department adopted and reorganized the movement at a national level. Murphy was brought to Washington as a dollar-a-year man to run it. Working with NAREB, he used the Portland plan as a model. He supervised the preparation of promotional materials, including a manual that suggested how to enlist the support of church, labor, and women’s organizations. He coordinated a new wave of local campaigns. The National Lumber Manufacturers Association vigorously encouraged local lumber dealers to become involved (Figure 3). As Jeffrey Hornstein notes, Philadelphia, under the leadership of realtors, was one of the earliest cities to mobilize. By March, twenty cities had signed up, and within a month the Washington Post reported that “virtually every large city already has initiated an ‘own your own home’ movement in the most enthusiastic manner.” These were led, variously, by the local real estate board (Milwaukee), the chamber of commerce (Chicago), the board of trade (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), and the local builders’ exchange (Toledo, Ohio). In May, the Department of Labor was joined by Agriculture, Commerce, Interior, and Treasury in promoting savings and thrift with “one objective—an ‘own your own home’ campaign.” In June it submitted what the Times reported as an “own your own home bill.” (The ill-fated Calder-Nolan Bill, ardently supported by NAREB, would have established a home loan bank.) By then, the campaign had been picked up by reformers associated with the National Housing Association, and over a hundred cities were on board. At a time when construction costs were rising rapidly, the main problem was that of securing affordable finance—Murphy received many complaints on the subject. Here, too, his office acted as a guide and information exchange.27

3. Own your own home. The lumber industry threw its weight behind national and local campaigns to promote home ownership after 1918. This copy of the campaign handbook was donated to his university library by Harvard professor James Ford, who played a significant role in promoting better homes during the 1920s. Source: National Lumber Manufacturers Association, “Own Your Own Home”: Campaign Handbook (Chicago: National Lumber Manufacturers Association, 1919.)

With help from realtors and local chambers of commerce, the Department of Labor also helped establish that modern marketing staple, the home show.28 Other industries had already begun to mount daylong or weeklong events. In January 1900, the first automobile show was held in Madison Square Garden; it became a fixture. In 1919, the Times reported plans for “a new kind of exposition.” Including displays by building and loans, it was “only a part of the greater work which is just being started by the New York Own-Your-Own-Home Committee.” The timing—September 6–13, towards the end of the building season—was less than ideal. Grander, and better-attended, next year’s was sensibly held in February. Led by Wilson Compton, head of the National Lumber Manufacturers Association, and by representatives of dealers and wholesalers, lumber interests alone secured 2,370 square feet of space. Model homes were built, while lectures were offered on domestic science and home finance. Thousands lined up to get in, while a reporter declared that “never before in the history of the United States has there been such an interest in homeowership.” He was probably right; certainly, home shows became the norm. In 1923, the organization of New York’s fifth annual show was taken over by local real estate boards, who never looked back. The idea was being adopted even “by the oldest and most conservative Real Estate Boards in the country.” They were encouraged by NAREB, which had received the baton from the Department of Labor for directing the entire OYOH campaign. By 1923, NAREB ran a large, slick operation. That fall, representatives from forty-seven national building industry groups assembled for a two-day meeting at its Chicago headquarters. Expositions or shows—the terms were used interchangeably—now went on the road, on a tight schedule within five regional circuits. NAREB established an advisory service for places not on the itinerary: for consistency and to maintain standards, expositions were licensed.29

For several years, the OYOH campaign coexisted with efforts to promote thrift. When S. W. Straus formed the American Society for Thrift in 1913, he made no mention of housing. By March 1919, however, he had come to see home ownership as the society’s main purpose. Noting the success of the government’s Liberty Bonds, he argued that in peacetime “no object could be more worthy of the practices of economy than one’s own home.” The federal government agreed. In October 1919, the Treasury designated the first National Thrift Week, beginning January 17, 1920. Business organizations, including those of bankers, building and loans, and construction industries, drew up a “ten commandments for household finance.” The sixth was “own your own home eventually,” and the group designated Tuesday, January 20, as “Own Your Own Home Day.”30

At this point the YMCA became involved. Real estate was a commercial field in which the organization had provided instruction for years; NAREB itself was formed in 1908 in a Chicago YMCA hall. Once Thrift Week was announced, the Y began planning a national campaign to reflect its general concern for the “physical, mental, spiritual and social development of mankind” and its specific support for home ownership. By mid-November 1919, its promotional plan had been “approved by the construction industries of the country” and entailed “vast publicity.” Soon, the Y was taking the lead. By January 1920, media reports suggested that Thrift Week was being “sponsored” by the National Thrift Committee of the International Committee of the YMCA. For several years, the organization took charge of the marketing of Thrift Week and worked with real estate interests to promote home ownership.31

The YMCA gave credibility to a campaign that from the early 1920s was largely run by NAREB and that might otherwise have appeared self-serving. Jeffrey Hornstein has observed that realtors claimed to carry a “special moral burden” in promoting home ownership, but this could appear disingenuous. And so when they backed the first Thrift Week Own Your Own Home Day, NAREB emphasized this was not part of a sales campaign. The National Lumber Manufacturers Association took the same approach in the handbook it published in 1919. It suggested that local campaigns should be placed under the auspices of the chamber of commerce and aim for “civic betterment” rather than implying “a purely commercial” purpose.32 Locally, real estate interests used civic groups to give legitimacy to OYOH campaigns; at the national level, the YMCA filled a similar role.

Legitimacy was also provided by women’s organizations and, again, the federal government. Women had a greater stake in their homes than their menfolk. They spent more time there, were usually responsible for household management, and thus had greater interest in how homes looked and functioned. For some years, such interest had been fueled by campaigns for domestic efficiency. It is not unexpected, then, that women became involved in local home ownership campaigns from the beginning, individually and through groups and committees. Not surprisingly, in 1922 Marie Meloney, editor of a popular women’s magazine, The Delineator, asked the Commerce Department to sponsor her new housing program, the Better Homes in America Movement. Meloney’s debt to OYOH campaigns is obvious. According to Janet Hutchison, she was inspired by a home exhibit in Ohio. The methods she advocated, including the formation of local Better Homes committees, the designation of Better Homes weeks, and construction of model homes, were analogous to those pioneered by Paul Murphy and later refined by NAREB. And although her vision was one of “women’s activities, community service, and home economics education,” the line between these endeavors and commercialism was always blurred. An advertising agency distributed publicity. Locally, Better Homes Weeks drew support not only from women’s groups but also, inevitably, from businesses with stakes in building, selling, financing, or furnishing the home.33

Hoover supported Meloney’s new organization. He agreed to become its president, and instructed his department’s Building and Housing Division to cooperate. In 1923, BHA was incorporated as an educational foundation; James Ford, a professor of social ethics, was brought from Harvard to run it. A new headquarters was opened, a block from the White House. In 1922, the first Better Homes Week proved a “huge success.” That year, more than 500 local committees were formed and many built demonstration homes; the number doubled in 1923, tripled by 1926, and in 1930 as many as 7,279 were active. Meloney’s campaign was endorsed by twenty-eight state governors, leading federal officials including the secretary of labor, and of course the president. Reaching into so many communities, and often attracting strong local support, it acquired a high profile.34

There was, then, an unprecedented amount of activity directed at the promotion of home ownership from the mid-1910s onwards. It went under different labels. It engaged, and overlapped with, organizations that also endorsed thrift, moral uplift, and home economics. It inspired promotional days and weeks, at both the local and the federal levels. At different times, it brought together federal departments (Labor, Commerce), nonprofits (the YMCA, Better Homes in America), and business groups with a stake in real estate (realtors) and the local economy (chambers of commerce). For the first time, then, it becomes possible to speak of home ownership as a national goal, although never debated or articulated as such by Congress. It is difficult to disentangle the separate impact of these agents and forces. The significant fact is that, while the labels and details varied, they perceived a common purpose. As Jeffrey Hornstein has put it, they believed that “the dominant notion of ‘home’ in America [had become] a detached, single-family dwelling, which became a home not merely by virtue of habitation or character but by virtue of ownership.”35 But what, exactly, was at stake here?

The Stakes in Home Ownership

As they warmed to the theme, boosters compiled a long list of reasons why families, especially, should buy if they could. Eventually, they naturalized home ownership, making it appear to be a situation that was then, had always been, and forever would be ideal. But while some arguments had become familiar by the 1910s, others were quite new.

Among the more familiar claims on Charles White’s list was the issue of short- and long-term security. The owner, he observed, is “not obliged to move from pillar to post at the will of his landlord” while mortgage debts, which “keep him toiling, grinding, to provide payments for his house,” will promote the sort of thrift that will provide an income in old age. After 1918, boosters such as Coleman Woodbury, Hazel Kyrk, and Herbert Hoover, as well as cautious commentators such as Benjamen Andrews, repeated such arguments. But, evenhandedly, they also expressed doubts about whether, even in the long run, owning was cheaper than renting. If they raised the issue of capital gains, as Hazel Kyrk did in 1929, they remained agnostic. The traditional case for home ownership was not a slam dunk.36

From the mid-1910s, new themes were emphasized or introduced. One issue—control over one’s lived environment—became more prominent, and was cast in a new light. In 1914, White spoke of an “inherent desire . . . to be one’s own lord and master” and argued that the home owner was not “constrained to adjust his mode of life to the pattern of a rented house.” By the 1920s, freedom was framed more positively as the opportunity to make improvements. As Hazel Kyrk noted, “All members of the family, young and old, strong and feeble, may use their ‘spare’ time in the upkeep and improvement of the home.” This could involve painting and making repairs as well as, “if skilful,” projects like adding a porch or window, laying a walkway, or building a garage, the latter being preferred by owners of older homes. Such efforts had an economic aspect, “augmenting the real income of the family in ways that otherwise would not be open to it.” They also had a moral purpose, since “home ownership offers ways by which men and boys especially can make themselves useful when they would otherwise be idle.” We see here a tangible glimpse of the companionate marriage that was emerging in this period, where women’s place in the kitchen was now being complemented by the man’s place on the ladder or, soon, in a home workshop. And they also had psychological and expressive qualities. “One of the motives for home ownership,” Kyrk claimed, is that “the family may build or rebuild something according to its own ideas.” More was involved than mere freedom from constraint; she suggests there is an “enjoyment that comes with a continuing pre-occupation of this sort.” This is surely what Herbert Hoover had in mind when he declared that “a family that owns its own home, takes pride in it, maintains it better, gets more pleasure out of it . . . The home owner has a constructive aim in life . . . [and] spends his leisure time more profitably . . .” Home ownership had always meant freedom from; by the 1920s more people reckoned that it also offered an opportunity to.37

The wholly new element to the postwar rhetoric is that it speaks of citizenship and civic advantages. Some had long been apparent. Notably, as Charles White pointed out, “owners usually take better care of their own property than renters do of the landlords’,” or than absentee landlords do of investment property. Hoover, among many others, alluded to this. But soon swamping such considerations were the political implications. From 1918, a growing chorus of voices suggested that home ownership provided a bulwark against the Bolshevik tide. Hoover framed it this way: “[Home owners] have an interest in the advancement of a social system that permits the individual to store up the fruits of his labor.” This was a response to the waves of radicalism and labor unrest that had washed over Russia, Europe, and North America between 1917 and 1920. Since radicalism was often based in immigrant communities, it awakened nativist sentiment. It is likely that, as Regina Blaszczyk has suggested, “nativists came to see ‘home sweet home’ as a proving ground where the unwashed immigrant masses might learn to became more like them.” The irony is that immigrants were already persuaded of the merits of owning property. It was the middle class that needed reeducating.38

With political tensions running high, owning a home swiftly became a duty, “moral, civic, and political.” Charles McGovern has argued that, in the early twentieth century, advertisers embraced a “cultural nationalism . . . asserting that their products were central to a specifically American mode of living.” The most significant arena within which this shift occurred—and very rapidly, too—was the housing market. As LeeAnn Lands puts it, in 1918–1919 the slogan became “Be a Patriot, Buy a Home,” a new emphasis on Americanism that, in its whiteness, implicitly excluded African-Americans. George Reynolds, president of the Continental and Commercial National Bank of Chicago, declared that buying a home was a “patriotic duty,” not just to help create jobs for returning soldiers but to express “citizenship.” S. W. Straus saw it as a “bulwark against the encroachments of bolshevism” on the domestic front, and as part of “a nation-building process.” As the radical threat abated and immigration controls took effect, the tone moderated, but it left a residue. Marina Moskowitz has shown how a middle-class standard of living emerged between the 1890s and the 1920s. By then, she suggests, “the maintenance and improvement of domestic property became one of the bonds of middle class communities.” “Bonds” maintain community, but they also constrain and, potentially, exclude. Families were increasingly expected not only to buy homes but to use them in particular ways. If home ownership had emerged as a new “ideal cultural aspiration” the implication was that those who fell short had failed, while those who rejected it became deviant.39 In sum, there was a new “odor of political sanctimoniousness” on the subject.40 Home ownership was ceasing to be a plausible choice for the middle class and becoming a social expectation.

What caused this shift? Margaret Marsh has suggested that booster rhetoric, and associated campaigns, amounted to “popular manipulation.” In fact, however, from the very beginning the campaigns were enormously popular. At first the defensive element was dominant, binding together patriotism, nativism, and an invocation of private property against a new Bolshevik threat. By the mid-1920s, a more positive outlook emphasized new possibilities, including the opportunity to shape one’s living space. The ownership campaigns of the 1920s gave coherence to a change in attitudes among the middle class. In that sense, they had an impact. But they also expressed that change, and were sustained by it. A social movement was producing a new ideology of home ownership.

An Emerging Consensus

Advice manuals show that the new ideology change did not emerge overnight. By the 1920s, these publications usually addressed the issue of home ownership, showing that the subject was now widely perceived to be important. But most remained neutral on the subject. This was even true of Christine Frederick, now known as a booster of suburban consumption. In 1923, she acknowledged that “whether to rent or own is a big question” and insisted that the answer is “to be only determined by the individual family, the location and the profession and permanency of the work of the father.” This almost defines noncommittal. Four years later, Benjamen Andrews offered a similar, if even more vague, opinion: “Modern conditions . . . make a wise individual decision between renting and owning difficult.” Five years on, an early Depression text betrayed only a slight preference. Home ownership, the academic authors suggest, can offer “stability and a sense of pride”; thus, it is “worth careful consideration”; even so, any decision should reflect “sound reasoning rather than mere prejudice.” Such phrasing implies that popular opinion had run ahead of what sober professors would advise. Own Your Own Home may have tapped a powerful new wave of sentiment, but it had not yet become a social consensus.41

Still, the appearance of a small, first wave of manuals on house building does indicate the ramifications of this change in attitudes for the practice of home improvement. These manuals domesticated the persistent strain of anti-urban, agrarian opinion in Canada and United States. After 1900, this outlook was articulated by several writers. In Three Acres and Liberty (1907) and A Little Land and a Living (1908), Bolton Hall argued that urbanites could become self-sufficient by moving to subsistence homesteads that they built for themselves. He showed several examples. William Smythe articulated a more moderate version of this idea. In 1908, he launched a “Little Landers” movement that produced “garden cities” near San Diego, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Palo Alto. He envisioned a “Home-in-a-Garden,” an owned property with a small garden lot that, as he later wrote in City Homes on Country Lanes, would “get[] the rural savor into city life.” He assumed homesteaders would have only a “small outside income.” Articulating a similar vision, John McMahon spelled out its implications for house building. In 1914, with his wife and daughter, he moved from New York City and built a house in the commuter fringe, where they raised chickens, fruits, and vegetables. He described the process of using scavenged materials in The House That Junk Built (1915). In truth it was solid enough. Aiming at fireproof construction, and inspired by his neighbor, Thomas Edison, McMahon used concrete blocks, steel girders, and floor beams gleaned from a nearby bridge that was being rebuilt. His photographs reveal that the result was not an aesthetic triumph, but he saved money, got the house he wanted, and was able to own it. Two years later he published a manual for others who wished to achieve Success in the Suburbs by owner-building, a process that he argued had been made much easier by the development of new materials and tools, such as the hand drill and tool grinder; and by the sale of kit houses. Hall, Smythe, and McMahon spoke to the urban middle class—McMahon himself had an unspecified office job—and so did writers such as F. J. De Luce in Country Life in America, who were writing about the rewards of erecting summer homes and cottages. Such activities were not mainstream, but they are the earliest indicators of a change in middle-class attitudes toward do-it-yourself.42

The possibility of a do-it-yourself house, however, was far from a mainstream interest in the 1910s and 1920s. To be sure, there was much middle-class interest in house building, especially as the war ended. One type of publication, the catalog of kit homes that could be ordered by mail, had already made a mark. By 1920 these were complemented by a national plan catalog, produced by Standard Homes of Washington, D.C. What was most novel after 1918 were the consumer magazines. In 1917/1918, The House Beautiful ran ten articles that followed the building of a house, but owner-building was not entertained: “Of course,” the author notes, “Miss Reader’s Service had made her arrangements with a good contractor.” Then, in 1922, the architect Ernest Flagg published Small Houses in an effort “to improve the design and construction of small houses while reducing their cost.” It was not directed at the general reader, but when Harold Cory interviewed Flagg for Collier’s, he was inundated with a “flood of letters” from readers asking “Can I do it too?” Cory tested Flagg’s ideas by building his own home, a process described in a series of articles and then in Build a Home—Save a Third (1924). The savings came from better design; Cory himself supervised construction, but without doing “a lick of work.” In this, he was far more typical than John McMahon. Other book-length guides for the middle class were being published for “anyone planning to build.” As early as 1914, William Arthur had published The Home Builder’s Guide, which pointed out that “there are several dangers in an owner doing the work himself.” A decade later, Gilbert Murtagh’s Small Houses covered “moderate cost” homes, by which he meant those in the $5,000–$20,000 range. Even $5,000 would have bought a solid house in a respectable neighborhood. Such guides addressed the growing interest in home ownership on the part of the American middle class, on the assumption that “building a home” meant hiring a contractor.43

We can parse rhetoric. Better, we can observe what people did. To some extent we can do this for the prewar era: Olivier Zunz has shown that in early twentieth-century Detroit, for example, workers were almost as likely to own their own homes as were professionals. Since their incomes were much lower, we may infer that their ownership aspirations were relatively strong. How relative is relative, and when did this change? Evidence for Canada in 1931 and the U.S. in 1940 indicates that change did not happen overnight. A Canadian study examined the relationship between urban ownership levels and family incomes for men employed in twenty of the most common working-class and middle-class occupations in 1931. Not surprisingly, the families of men in higher-income occupations were more likely to own their own homes, but the correlation was far from perfect. Moreover, there was a systematic class difference. Those in white-collar occupations, notably accountants, professional engineers, and salesmen, had ownership rates that were lower than one would expect, given their income. Those in blue-collar occupations, including policemen, tailors, carpenters, and printers, were more likely to own homes that their income would suggest.44

Relatively low ownership levels among white-collar workers was also apparent for the urban United States in 1940. The U.S. data show ownership rates for income categories within each occupation group, making it possible, for example, to compare ownership rates for professionals and semiskilled workers with the same incomes. Within the $1,500–$1,999 family income range, which straddled the average, ownership rates were higher among those in blue-collar occupation groups, whether skilled (36 percent), semiskilled (28 percent), or unskilled (31 percent), than among most white-collar groups, including professionals (21 percent) and clerical workers (25 percent). Income is not the only factor that influences whether a family can afford to buy, but it is important. If large groups of people with similar incomes differed in their ownership of property, we must infer that aspirations varied too. Evidently, class differences in ownership preferences did persist until at least World War II.45

Indeed, for a while, it was not clear in which direction attitudes were moving. The 1920s saw a surge in apartment building. Some contemporaries speculated that this revealed a shift in popular preferences away from the single-family dwelling, and home ownership too. This was an issue picked up by Richard Ely, the leading real estate economist of the day and director of the Institute for Economic Research, and also by NAREB. In the late 1920s, Ely’s institute sponsored research by Coleman Woodbury into recent building trends. Woodbury documented the apartment boom and, through interviews, explored attitudes towards home ownership. Writing in 1931, he claimed to have found that many people “still” wished to own their own home, implying that costs and building regulations stood in their way. That same year he and a coauthor found more cause for disquiet. “There is little special prestige attached to the ownership of a single-family home,” they declared. Instead, middle-class families were drawn to the better amenities of modern apartment buildings. Women found the housekeeping easier, while men could golf and spend time “motoring.” From their point of view, the trend in attitudes was flowing in the wrong direction. “In late years,” they suggest, “it has become doubtful if the ownership of a home is really the goal of as many people as it was in the past.” Instead, they endorse “the common opinion that the funds formerly set aside for the purchase of a house and lot are now absorbed by installment payments” on other goods, including cars and radios. Worse, this might be part of a larger, almost inevitable, trend. They cited the New York Times as authority for the claim that multifamily dwellings were “the final break with the rural tradition, the last step in urbanization.” The clincher appeared to be that, as another study funded by the institute found, apartments were spreading into suburbs like Evanston, Illinois.46 It is doubtful that most contemporaries would have followed this argument to its conclusion, but many did believe that the apartment boom expressed a new middle-class taste.

Coleman Woodbury’s concerns, and perhaps some of the rhetoric of campaigns sponsored by NAREB and Hoover’s Commerce Department, were a defensive response to the apartment boom. But most home boosters believed the tide of history was running in their direction. Popular support for Better Homes in America suggests that they had good reason. This, at any rate, is the opinion of a number of historians. Marsh, for example, claims to have detected a “dramatic shift to a preference for home ownership” between the 1900s and the 1920s.47 Is it possible to reconcile such contradictory perceptions of the state of middle-class taste and, if so, how? Some reconciliation is possible. The most celebrated sociological study of the interwar years was Middletown, Robert and Helen Lynd’s comprehensive survey of Muncie, Indiana. The Lynds had much to say about housing, some of which is more revealing than they perhaps realized. Like Constance Perin in the 1970s, they found in 1920s Muncie “a deep-rooted sentiment . . . that homeownership is a mark of independence, of respectability.” But it is clear that, even if deep-seated, this was new. Elsewhere, they contrast the 1920s with the 1890s. In the earlier decade, they observe, “building houses to rent was a regular and lucrative type of investment,” but a generation later at least 90 percent of new single-family dwellings were being built for owner-occupancy. This is close to the figure that Lloyd Rodwin has estimated for 1920s Boston. Some of the rental properties built before World War I were for workers; most were occupied by the middle class who, like Americus Underdown, were content to rent. But then the demand for new rental houses collapsed, and so when Hazel Kyrk suggested why a family might wish to buy, her most telling comment was pure pragmatism. “In many communities,” she noted, “one must buy a house in order to secure play space for children, a good environment and a properly equipped dwelling.” In the 1920s suburbs, renting was not an option.48

Commentators like Coleman Woodbury had misinterpreted and overreacted. They were confused because two related things were changing, but on different schedules. First, a long-term shift towards the production of single-family homes was happening, but at first it was disguised by a temporary boom in apartment building. When this boom died with the onset of the Depression, the single-family dwelling trend asserted itself, quietly at first and then overwhelmingly after 1945. A second change happened more suddenly: from 1918, with local and minor exceptions, any new single-family dwelling was destined for owner-occupation, most probably by the middle class. Building workers’ homes was now unprofitable, while a new middle-class demand was firming up.

Looking back, we can see that the middle-class preference for home ownership had solidified by 1945. Significantly, this year saw publication of the first tract against home ownership, which asked “Is it sound?” Writer John Dean probed the supposed advantages of home ownership in turn, and highlighted its downsides. Sometimes his tone was almost shrill, indicating that he was battling an emerging consensus that was becoming hegemonic. This was made explicit in Robert Lynd’s foreword. Lynd deplored the fact that impartial advice was now unavailable. Instead, when the potential home buyer asks “ought we to buy?” he “receives in the main only one answer from every side: ‘Sure! It’s the American way.” Lynd also points out that families now had little choice about whether, or what, to buy. He speaks of the “coercions” of a development industry that was producing a suburban monoculture. The potential lack of choice that had troubled Hazel Kyrk in 1931 had become a reality. The timing of Dean’s book, then, was telling. In 1918, many Americans needed to be persuaded to buy homes. By 1945, homes sold themselves.49

The New Stakes in Home Improvement

By the early 1920s, the North American housing market was becoming recognizably modern. Hardly any housing was being built for the bottom third of the population, while the middle classes were busy committing themselves to home ownership. It was on this foundation that home improvement, as a social practice and as an industry, built itself. From the beginning, improvement created a dilemma: it sounded like a good idea, but it slowed the rate at which housing filtered down to the poor. A few observers saw the dilemma. For example, as the Depression was beginning to bite, Blanche Halbert acknowledged that “with costs as they now are families of low-income groups must necessarily live in the cast-off houses of families with more money.”50 But she could not approve the idea that middle-class households should let their homes deteriorate, and then move on, for this contradicted her view that owners should care for their homes, and indeed work to improve them. For Halbert, as for the growing middle class, when home ownership became a social norm so did home improvement.

The direct evidence on home improvement trends after 1918 is inconclusive. Charles White and Herbert Hoover assumed that home owners maintained their properties better than landlords, and they were surely correct. Owners have reason to care more about their homes, and gardens too. Gries and Ford reported research that showed home owners maintained their gardens better. Although some believed otherwise, this had little to do with race or ethnicity. In 1927 a survey of African-Americans in Richmond, Virginia, found that 69 percent of home owners but only 21 percent of tenants had “well-kept flowers and shrubbery.”51 When ownership rates rose, as they did during the 1920s, we might expect that expenditures on improvements would increase in tandem. There were the financial, moral, and psychological considerations to which Hazel Kyrk referred, including the desire to shape one’s living space. But, as newer subdivisions came to consist largely of home owners, peer pressure also played a part. As a consensus emerged about home ownership, norms of maintenance and improvement also rose.52

The probable upward trend in improvement cannot be demonstrated, however, with the available statistics, which are based on building permits, household expenditures, and/or income data. Many improvements were undertaken by owners themselves and were unrecorded; where tradesmen were employed, payments were often made under the table; either way, especially with interior work, jobs were completed without benefit of building inspector. As the Bureau of Labor Statistics commented in 1922, even where permits were required, “considerable building is done without permits because of laxity in inspection and in permit enforcement.” In some cities, in many lower-income suburbs, and throughout unincorporated areas, permits for improvement were not required. And so the available annual data on “additions, alterations and repairs” understate their significance. In the 1950s, studies in the United States and Canada indicated that available data underreported actual improvement expenditures by a factor of up to three.53 Who knows whether exactly the same ratio applied in earlier years. Regardless, when, as in 1921, permit data suggested that repairs and improvements accounted for 23 percent of residential construction, we may safely conclude that the real figure was a good deal higher. Fortunately, even imperfect data show annual fluctuations that carry meaning. The level in 1921 was a temporary high, coinciding with a dip in new construction. This improvement business still attracted only temporary interest from the trade. As the American Lumberman commented, remodeling jobs were a “fiddling” business that many contractors and dealers welcomed only when business was slack. The share of repairs and improvements declined during the construction boom of the 1920s, bottoming at 9 percent in 1925, but then reviving to reach 20 percent by 1929 (figure 4). A slightly later inflection point was apparent in Canada. It is hard to read anything into these fluctuations, except that they mirrored fluctuations in new construction. They do not reveal any obvious trend in home improvement.54

Do-It-Yourself

And yet, other sources suggest that something was happening. The available statistics overlook the modest repairs that owners were most likely to do themselves. This matters because women and men were showing some interest in what we would now call do-it-yourself (DIY). This slippery term, which refers to a type of activity, a particular context, and a mix of purposes, has been central to the growth of home improvement in the twentieth century. Clearly, it involves household members doing work that they could otherwise purchase as a service. “Could” is the key word. Settlers on the western plains built, decorated, and maintained their own homes but we would not normally say they engaged in DIY: they had no choice. The same was arguably true for immigrants who built and repaired their own homes in unplanned suburbs. At the suburban frontier, tradesmen were available, but immigrants could not afford to employ them. In practice, the market alternative did not exist, though barter and cooperation might substitute. Doing things for oneself was the norm; no special term was required.

4. The trend in home improvement in the United States, 1921–43. The available data consistently underestimate the magnitude of improvement expenditures, but usefully reveal trends. U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce, Statistical Abstract of the United States (Washington, D.C.: USGPO, 1936), table 830.

The idea of DIY and, with it, the term, emerged after 1900, when urban North Americans began to tackle improvements by themselves instead of hiring tradesmen. That is why Steven Gelber, one of the two writers to explore the history of do-it-yourself, argues that it should be understood as “neo pre-industrial” rather than traditional. The first usage of the term that he found was in an article on home decoration in Suburban Life in 1912. Author Garrett Winslow recommended “do-it-yourself’,” adding “and so wallpaper is out of the question.” Clearly, the practice was still rare and limited, and the term itself did not catch on. Instead, doing one’s own home improvements was referred to in various other ways in consumer publications. Noting the tradition of home crafts in which women, especially, took pride, Gelber notes how they were given a practical cast by Gustav Stickley when he founded The Craftsman in 1901. Carolyn Goldstein has also pointed to the founding of new magazines, notably House Beautiful (1896) and House and Garden (1901), though these emphasized taste over tasks, as did Hooper’s book, Reclaiming the Old House (1913). More practical were Popular Science and Popular Mechanics, founded in 1903, which soon reoriented themselves away from engineering reviews and offered advice to amateurs. Gelber suggests that after 1918 there was a “dramatic” increase in DIY literature. The date is about right. In 1000 Shorter Ways around the House (1916), Mae Croy gave women tips on, among other things, house design and decoration, but only one passing suggestion implied that householders might do things for themselves. (For screens, use thinned paint.) In 1917, John McMahon included a chapter for amateurs on home remodeling in his book on suburban owner-building, while Archie Collins produced The Home Handy Book, a compendium of useful home-maintenance tasks.55

McMahon and Collins were slightly ahead of the curve: it was not until the early 1920s that a significant number of authors and publishers perceived a growing market for improvement manuals. A pioneer work was Allen Churchill and Leonard Wickenden’s The House Owner’s Book. Published and reprinted in 1922, and reprinted again in 1923, it clearly met a need, catering to a new interest that, according to its authors, had been “greatly stimulated” by recent OYOH campaigns. It offered advice on building or buying a home, and also on “how to keep your house in repair.” The authors spoke to those who wished to save money, but also the man who “prefers to run his own house, to tinker about . . . in short to be a real house owner.” The use of “real” is telling in an implied moral judgment that is elsewhere made explicit. The home owner, Churchill and Wickenden claim, is a “member of a neighborhood or community,” as opposed to being a mere “floater.” And the home should be a source of pride, “a hobby.” There is the suggestion from these authors that owning wasn’t quite enough: being handy made the man. As yet, however, this expectation was generally muted.56

The success of The House-Owner’s Book invited competition. In 1923 Amelia Hill brought out Redeeming Old Houses, a specialized work dealing with second homes for families of “moderate means.” Assuming that the “country householder will . . . do much for himself,” she offered tips about tools. The following year brought Lescarboura’s Home Owner’s Handbook, already published serially in Scientific American, and Saylor’s Tinkering with Tools, the first chapter of which was actually entitled ‘Do It Yourself.’ These were followed by Fraser’s Practical Book of Home Repairs (1925); Your House, McMahon’s new offering which assembled pieces already published in Country Life and Popular Science; Wakeling’s Fix it Yourself (1929), most of which had already appeared in Popular Science; Dorothy and Julian Olney’s Home Owner’s Manual (1930); Phelan’s The Care and Repair of the House (1931); Halbert’s Better Homes Manual (1931), and, the most modern-sounding of all, Schaefer’s Handy Man’s Handbook (1931). And so by 1931, in their own guide, John Gries and James Taylor could report that there were “numerous household manuals” on the bookstands.57

None of the household manuals of the 1920s encouraged home owners to be ambitious. Churchill and Wickenden set the tone: “There is no intention of driving the builder, carpenter, plumber or painter out of business,” they insisted, for “the house owner will learn quickly the limit of his capacity.” Phelan distinguished between jobs that “require special knowledge and skills”—which included electrical work—and those that “can be performed by the householder who is handy with tools” and so could effect some repairs and “minor improvements.” The Olneys were blunter: “There is a naturally a limit beyond which the home-owner should not attempt to go in making adjustments and repairs.” Making cupboards and occasional repairs to the plumbing were OK, but not “structural changes.” These authors followed Hazel Kyrk in assuming that their readers’ main concern would be to save money or, perhaps, to handle an emergency. The Olneys comment that “much money can be saved,” while a plumbing job might be “thrust upon us occasionally by dire necessity.” At the same time, however, and again like Kyrk, they concede that necessity did not drive everything. They speak of the “fine sense of satisfaction” and even the “accompanying joy” of work on the home. Collins, as well as Churchill and Wickenden, refer to the “pride” of the owner-hobbyist. Saylor, too, introduced Tinkering with Tools by deploring specialization and by praising the “work hobby.” This helps to explain the paradox, noted by Gelber, that although DIY “produced outcomes with real economic value,” it “might actually cost more in time and money than the product was worth.” Tinkerers and handymen had options; they were middle class; they wanted to save money, certainly, but they were also driven by social and psychological goals. For them, DIY was not just a necessity but a nascent cultural norm.58

The most obvious aspect of DIY—that it involves work on the home—is also the most revealing. It is generally seen as men’s work, although even in the 1920s the stereotyping was incomplete. Writing during the war, when many men were away from home, Collins was careful to make no assumption about whether a “he or she” would be fixing the faucet, replacing the broken window, or wallpapering the living room. After 1918, such neutrality was more typical of female authors. In their Manual of Home Making (1919), Martha van Rensselar and her coauthors advised women to keep a “repair kit” that included hammer and nails, screwdriver and screws. The woman was responsible for acquiring such a kit and, possibly, for using it. In 1923, Amelia Hill assumed that in the family’s second home, left with the children while her husband worked in the city, the wife was likely to be responsible for repairs. Chelsea Fraser would have viewed this with equanimity. In his Practical Book (1925), he claimed that twelve years teaching public school had convinced him that girls and boys were “equally” capable of learning the skills of home repairs, though he allowed that boys were better at heavy work. Not surprisingly, then, in 1931 Gries and Ford observed that woodwork could be refinished “by the house owner himself or some member of his family,” by which they might have meant a son or spouse, though probably not a daughter. Even so, as Gelber comments, the idea of women working on the home was still a “novelty.” Fraser may have supposed that girls could learn the same skills as boys, but a frontispiece shows “father and son painting own home in their leisure hours.” The fixup manuals were for handymen. As the Olneys put it: it was up to “the man of the house” to take “proper care of the home” through “a knowledge of the physical make-up of his abode,” and of how to maintain it.59

The available evidence confirms a clear gender division of labor. In 1900, for example, Miriam Andrews of Hudson, Wisconsin, picked out some new wallpaper that her husband, James, then put up while she went away to stay with her daughter. Reporting this, Joan Seidl comments, “Miriam’s overriding desire was to see the wallpaper up, not necessarily to hang it herself.” A generation later, a national survey of 331 households of professionals and managers painted a fuller picture. It found that in 1927, men did indeed “help” around the home. At a time when most households relied on coal for domestic heating, most men (72 percent) fired the furnace or stove. That apart, their most common domestic commitment was that of repairing and maintaining the home (31 percent), while 10 percent repaired household equipment. Men did participate in some “domestic” work: caring for children (15 percent), and preparing meals (9 percent), but their house cleaning was confined to the basement or garage, stereotypically male spaces. Women worked in the home, while men worked on it.60

Except for domestic servants, the women who worked at home were unwaged while most of the men who worked on the house—that is, building tradesmen—worked for pay. In middle-class households, a growing shortage of servants meant that women did more of their own chores. Ruth Cowan refers to this as the rise of women’s do-it-yourself. This usage is reasonable, since a market alternative existed, but was anachronistic: to this day, DIY refers to work done on the home, and usually by men. This is telling. Even in middle-class households, the idea that the woman might do housework was no novelty. But the emerging interest of men in home repairs and improvement called for recognition. And so the accepted social meaning of do-it-yourself speaks not only of a gender division of labor but also the novelty of men’s engagement with the home.61

Part of the domestication of men involved their taking on domestic activities, such as gardening, that had previously been viewed as women’s preserve. Margaret Marsh argues that such “domestic masculinity” emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Gelber speaks of a second aspect as “masculine domesticity.” It saw men doing work on the home that was stereotyped as male but which husbands now did for their own families instead of hiring another man for pay. Clearly, these aspects were related. Both meant that middle-class men were taking more responsibility for the running of the home. Significantly, although nineteenth- and early twentieth-century manuals on household management had been addressed to women, by 1932 Mildred Wood and her coauthors could claim that “the patriarchal family is passing.” Instead, they spoke of “joint responsibilities.” But if there was some loosening of gender roles, it was largely confined to the middle class, while the rise of masculine domesticity had a distinctive identity. It emerged later because, uniquely, it depended on the new norm of home ownership that had emerged after 1918.62