FIVE

The Birth of the Home Improvement Store

By the 1920s, retail yards were being torn between loyalty to the lumber trade and the growing incentives to go after a new consumer business, to remained specialized or to diversify. This tension was expressed at annual meetings as a conflict between sentiment and self-interest. It was never that simple. Loyalty was based on business ties and expressed common interests. But the lumber trade had long been a house divided, and the divisions grew. After 1905, when a new group of lumbermen developed a new business model, the very conception of the lumber retailer was transformed, laying the basis for the emergence of a more diversified retailer of building supplies who could cater to a home improvement business.

A House Divided Against Itself

Retailers occupy a fragile place in the distribution chain. As middlemen, they can appear less essential than producers, and they are the first target for complaints about prices. When manufacturers try to sell directly to consumers they are guaranteed a sympathetic hearing. This has not prevented retailers from resisting direct sales, but such resistance has been deplored and sometimes challenged in the courts. The lumber trade, circa 1900, is a case in point. By the early 1900s, prosecutions under the Sherman Act had created a negative public image of “the Lumber Trust.” Despite the label, this was not monolithic. Legal action was taken against manufacturers for price fixing, but many court cases charged retailers with collaborating against manufacturers who sold direct. Then too, as Butler noted in 1917, retailers and manufacturers sometimes put their heads together to retaliate against unscrupulous wholesalers. In sum, it was common for branches of the lumber industry to be at each others’ throats.1

Retailers perceived that direct selling, whether by wholesalers or manufacturers, was the greatest threat to their livelihood. Indeed, it was this concern that first drove them to create associations. The first was formed in Iowa on June 8, 1876, to target wholesalers who sold to consumers at the same price as to dealers. In 1877, the Northwestern Lumberman helped establish a larger association that fined Chicago wholesalers for selling direct, boycotting those who refused to pay. As William Cronon has pointed out, once wholesalers complied the association faded away. Looking back in 1915, H. C. Searce, secretary of the Retail Lumbermen’s Association of Illinois, generalized. “The original and almost sole purpose of the retail trade association was to protect its members against the sale of lumber direct to the consumer.” He was unapologetic. “Big stick methods were used, and justifiably so.” The boycott was the biggest stick, backed by the black list. In an early use of the Sherman Act, for example, the Northwestern Lumber men’s Association was charged with this tactic in 1892. Occasionally, dealers boycotted contractors who bought direct, and in 1894 the Nebraska Lumber Dealer’s Association was found guilty on this count. When, twenty years later, a federal district court found against yet another association, the New York Times reported that “the court . . . noted the friction which always existed between the wholesalers and the retailers” as one or other were accused of “invading its special field.”2

Such jousting abated during the 1920s, but resumed during the Depression. The federally sponsored Lumber Code had been strongly endorsed by the whole industry in 1933, but its influence was short-lived. A survey for the National Recovery Administration in 1936 spoke of disorganization and gloom. The author recounted a succession of failed attempts to introduce production controls from 1928 onwards. In that year alone, efforts included the formation of a Committee of Fifteen, an abortive alliance with producers of oil and coal, a privately sponsored idea of a Director of Production, a Holding Company and—a federal suggestion—a Timber Conservation Board. The latter was approved in 1930 when the Compton Plan, promulgated by the president of the NLMA, also flopped. In 1931, the Southern Pine Curtailment Plan and the Wisconsin Stabilization Agreement helped stall a decline in prices, but this was temporary.3

The Lumber Code of 1933 fared little better. Business was way down, and the whole trade was again riven by “warring trade organizations.” Wholesalers had retaliated against retailers who bought direct from the mills, and this triggered “the bitterest kind of competition.” Such battles, Stone concluded, “played a large part in breaking down Code prices and the Code [itself].” The Middle Atlantic Lumbermen’s Association set up a purchasing corporation to circumvent wholesalers and browbeat manufacturers. Intense opposition forced them to back down. And so it went on. In 1947, Nelson Brown observed that retailers “generally have refused” to buy from wholesalers or mills that sold directly to the consumer, except for railroads and large industries. Behind this neutral statement lay an armory of tactical weapons, an ebb and flow of strategic battles, a whole history of mistrust. Wilson Compton and others liked to speak about the lumber trade as an extended family. Perhaps. After all, families can be dysfunctional; members squabble, stop talking to each other, and may eventually walk out. What prompted dealers to think seriously about leaving the lumber family was the emergence of mail-order competition.4

Mail-Order Competition

After 1905, a growing number of companies caught on to the idea of selling building materials from catalogs they distributed by mail. The timing was not coincidental. As Daniel Boorstin has noted, mail-order operations in general were boosted by the introduction of Rural Free Delivery, which enabled retailers to distribute catalogs inexpensively to millions of households. The main rural routes were established by 1906. This coincided with a boom in building after the depression of the 1890s, and also with a surge of antitrust action against manufacturers. Here was a new business opportunity, and a mail-order business for building supplies was soon growing rapidly.5

Urban and architectural historians have written about the mail-order housing business.6 They have rightly emphasized the effectiveness of the mail-order companies, notably Sears, Roebuck, in marketing house kits. These were more or less complete packages of materials, that could be assembled on site. But historians have downplayed the fact that the first companies to enter this market, notably Aladdin, emerged from the lumber trade. These upstarts were sophisticated wholesaler/manufacturers, shipping direct to the consumer. More significantly, previous writers have neglected the effect of the mail-order business on the organization of the existing building industry, including the retailer. In the long run, this was the effect that mattered most. For a time, many consumers were indeed drawn to the kit. By 1930, about 350,000–400,000 packages had been shipped across the United States and Canada.7 But only a minority of mail-order companies survived the Depression, and even those failed to prosper. Their enduring significance lies in their effect upon other retailers of building supplies. Here, the catalogs are revealing, for they indicate how companies tried to insert themselves into local building industries.8 The trade press then shows when and how those local businesses responded.

The first mail-order operations sold lumber and competed on price. Gordon-Van Tine, of Davenport, Iowa, one of the larger concerns, entitled its promotional material Our Price Demolishing Lumber List: Lumber at Rock Bottom, Mill-to-You Figures. This was the direct-sale competition that retailers detested. Price lists became catalogs, and the trade press damned their distributors as “catalog houses.”9 But dealers sometimes found it hard to decide which of these were acceptable. Vertical integration blurred the line between manufacturer, wholesaler, and retailer. Any might publish a catalog, and if it respected established channels of trade then it was acceptable. The hard part was knowing. In 1914, for example, the Mississippi Valley Lumberman (MVL) confirmed that a “newly organized” company with “somewhat sensational” advertisements was a bona fide wholesaler committed to using retailers. A correspondent claimed that another company, Doty Lumber and Shingle, had either sold to Gordon-Van Tine, by then a kit distributor, or sold by mail themselves. Lines were drawn, and policed.10

Price was the strength of the catalog house, and its weakness. Bennett, of Tonawanda, New York, declared “we undersell,” so that “you buy at wholesale prices.” Competition was fierce, margins narrow, and temptations to cheat were strong. Doty Lumber wrote to dealers, offering not to sell to customers in each yard’s territory, if the dealer agreed to purchase a carload of lumber: blackmail. The railcar unit mattered, since shipping rates were higher for smaller quantities. They were also higher for millwork than common stock. A large catalog company, Hewitt-Lea-Funck of Seattle, was found guilty of mixing grades in its cars, and it was also accused of shipping inferior goods. It was hard to make this charge stick, since lumber grading was not standardized and varied by species. Still, Gordon-Van Tine was found guilty of shipping oak veneer instead of the real thing. Some companies, like Gordon-Van Tine, cleaned up their act. Other companies, such as the Central Mill and Lumber, of Colville, Washington, could not survive without scams.11 The competition for, and with, mail-order lumber was ugly.

Until the 1920s, mail-order shipments were confined to rail transportation, and buyers had to arrange carriage from the rail depot to building site. Rosemary Thornton, who has undertaken fieldwork on Sears, Roebuck houses, suggests that few were erected more than two miles from a railroad. More generally, mail-order companies never accounted for more than 5 percent of the lumber sold to customers, even in the Midwest.12 But their presence became a leading topic at association meetings, and by 1914 an obsession of the trade press.

The threat was real. Catalog companies threatened to shave the dealers’ narrow margins, or eliminate them entirely. As late as 1914, the main threat was still cheap lumber. In that year, the MVL listed the major catalog houses. Of seventeen listed, only four produced kits. Of these only one, Gordon-Van Tine, had graduated from selling wholesale lumber; another, the Chicago House Wrecking Co., had begun by selling used materials from the Chicago World’s Fair; only the remaining two, Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward, had entered the kit business from outside the lumber trade. (Though even Richard Sears’ first retail operation, begun when he was employed as a station agent, involved the sale of lumber and coal.) Significantly, the MVL mentioned these two companies only because they sold lumber. Other kit companies, including Aladdin, were ignored.13

The Kit Companies, 1905–1929

By 1914, the mail-order threat to the local retailer was changing. In 1900, the Hodgson Company had begun shipping garages; in 1905, it opened a factory to produce summer cottages and houses. The following year, Gordon-Van Tine was selling house plans along with lumber, and the Sovereign brothers started Aladdin. In 1908, a contractor and a lumberman teamed up to start Pacific Ready-Cut in Los Angeles; the building materials department at Sears, Roebuck, published its first catalog and soon Sears offered its first complete bill of materials for a house. By then, according to Platt Walker, editor of the MVL, the kit producers were having an impact. In 1910, Montgomery Ward and Gordon-Van Tine began offering “ready-cuts,” i.e., kits, and next year Sears opened a mill in Cairo, Illinois, and created a modern homes department that offered credit—a first. These initiatives raised their operations to a new level.14 Before the United States entered World War I, other companies entered the fray: large concerns like Harris Brothers in 1912, Lewis Manufacturing in 1914, and the International Mill and Timber Company (a.k.a. Sterling) in 1915, as well as smaller aspirants such as Tacoma’s Local Lumber Company, which in 1914 opened an “eastern sales office” in Mitchell, North Dakota, to sell “complete house and barn bills.”15 Business picked up: in 1914, MVL reported that mail-order companies were “more persistent and active . . . during the last twelve months than ever before.” Trade journals began to distinguish “regular” mail-order competition from the newer “ready made houses.”16

Production of kits was taking off. The only available sales data pertain to Aladdin, the largest operator until the 1920s, and its experience is indicative. In 1914, its annual sales exceeded 1,000 units; by 1916 they reached 2,500 and in 1917 peaked at 3,200. In 1918, supplying the U.S. government and industrialists, for company towns, Aladdin shipped the materials for about 2.4 percent of all new homes across the United States. Kit companies were beginning to make inroads into the business of local retailers. In 1918, when Shaw surveyed dealers across North America, he devoted a whole section to the topic “how to keep your trade at home.”17

For a time, the kit companies gained strength. Most boosted sales by offering a new service, credit. Quotations now came with a cash discount, usually 2 percent.18 Buyers could send a deposit of 10–25 percent and pay the balance on delivery, or arrange for a letter of deposit with a local bank, which guaranteed the vendor of sufficient funds while allowing the buyer a few days to inspect materials when they arrived. Sears, Roebuck, Pacific Homes, and Harris allowed buyers to make progress payments as the house went up—a construction mortgage. Finally, as the pièce de résistance, was the full easy-payment plan. Sears had discontinued this in 1911–1913, but in 1915 it was adopted by International Mill, which required 60 percent down and repayment over two years. By 1920, Sears offered a more generous plan which was extended to 100 months, and in 1928 further still.19 It then offered cash-back funds to pay for construction so that, in effect, down payments were reduced to 35 percent, then 25 percent and, for those who dispensed with contractors and built their own homes, virtually to zero. Boosted by financing, kit sales boomed again. Aladdin’s stagnated in the early 1920s before surging to peak at 3,400 in 1926. Sears’ peaked later, 1926–1928, when the company might have shipped 4,500 kits a year, or about 1.3 percent of all housing starts. Among the major catalog houses, only Pacific Homes and Montgomery Ward in the United States, and the Canadian department store Eaton’s, failed to joined the credit bandwagon, boasting that “cash on the barrelhead” saved customers money. Pacific, which offered construction finance, managed well: its sales picked up in 1921 and peaked at 4,000 in 1925.20 But the cash requirement surely limited sales at Eaton’s and Montgomery Ward.

Kit manufacturers came in all sizes. One was continental. By 1919, Aladdin opened a sales office in Toronto, and operated nine mills across the continent, three in Canada. It soon listed customers in forty-seven states—and in Australia, England, Liberia, Tahiti, and Switzerland. This inspired its claim that “The Sun Never Sets on Aladdin Houses.”21 Although it eventually surpassed Aladdin, with sales of 34,000 by 1926 and perhaps 70,000 houses by 1933, Sears confined itself to the United States, where it sold nationwide. So did Montgomery Ward, Pacific Homes, and Gordon-Van Tine. Pacific claimed sales in Alaska, Hawaii, South America, and England, while Gordon-Van Tine published a testimonial from Guantanamo, Cuba.22

Other companies never quite reached a national market. Pacific Ready-Cut, featured in Buster Keaton’s silent comedy One Week (1920), extended its reach throughout the southwest, and into some eastern states; in Canada Eaton’s, which sold kits from 1911 and published a catalog in 1912, was headquartered in Toronto but shipped lumber from the west coast. It had few customers east of Ontario. The U.S. midwest was the ideal base. Apart from Aladdin, two companies in Bay City, Michigan, reached for a national market: Sterling and Lewis. Their best sales were regional and, for Lewis, on the east coast: its prices included free shipment within the midwest and the Atlantic states from North Carolina up.23 A regional focus was clearer for Harris (Chicago), Bennett’s (Tonawanda, New York), and Hallidays (Hamilton, Ontario). Bennett’s testimonials came mostly from upstate New York and Pennsylvania, while Hallidays sold in southern Ontario, with a sprinkling eastwards. Other companies, such as Bossert, Evansville Planing Mill, Tumwater Lumber, and National Mill (in spite of its name), were never more than subregional. In 1927, Evansville Planing, of Indiana, claimed to offer eighty-two types of “standardized homes” for shipment to “all parts of the country,” but there is no evidence that it came close to that goal.24 Like Evansville, many kit manufacturers depended more on word-of-mouth and local advertising than on mail-order business. They blurred with the local dealer.

Although kits had their greatest impact in the midwest, they were sold all over the country. They found their way into the suburbs of major cities from coast to coast, but most ended up in smaller urban centers. This was typical of the mail-order business in general. Company records have apparently not survived but published testimonials suggests their geography. In 1924, the Bennett Lumber Co. published eighteen, all from places like Six Mile Run (Pennsylvania) or Seneca Falls (New York). In 1923, Gordon-Van Tine published a page of forty-eight testimonials, forty-six of which were given a home town. One was large (Philadelphia), and two mid-sized (Indianapolis, Rochester), but the rest were small towns scattered across the eastern and midwestern states, from Hooker (Oklahoma) to Minden (Nebraska), and from Barre (Massachusetts) to Eureka (Utah), but with a bias to Gordon-Van Tine’s home state, Iowa (Davenport, Grinnell, Mason City, Grand Junction, Riverside, Exira) or to neighboring Illinois (Caseyville, Illiopolis, La Salle, Roseville, Springfield). A similar pattern was apparent in Canada. There, from Hamilton Ontario, Halliday sold to buyers in a few small cities (Hamilton, Guelph, Windsor) and a myriad small towns, from Ancaster and Arden, through Oshawa and Orillia, to Willowdale and Woodstock.25

In 1925, Aladdin trumped everyone, publishing a list of over a thousand customers, organized by state. This was probably not a geographically representative sample: the company wanted to name as many states and places as possible. But a predictable pattern emerged. Among the customers in Ohio, for example, none were in Cleveland, and only one in a Cleveland suburb (Bay Village); one was in the state capital, Columbus. The rest were in towns like Lancaster, Mansfield, Steubenville, Pleasantville and—a real concentration here—Zanesville, with nine listings. Perhaps the word had gotten around, or Aladdin had converted a local contractor. Either way, in Ohio as elsewhere, the small-town bias was overwhelming.

Selling the Consumer

Marketing kits was different from catalog lumber. The customer was a consumer, not a contractor, and clever advertising was necessary. At first, manufacturers targeted the rural market and advertised in magazines like Wallace’s Farmer. In some regions, this was big business, nowhere more so than on the Canadian prairies, which lacked local lumber and where settlement was rapid after 1900. B. C. Mills, the main kit company on the Canadian west coast, offered farm plans and made an excellent business out of them. The only large company with a distinctive business model was Hodgson, which used bolted-panel technology; which targeted niche markets for cottages, play and guest houses, camp equipment, and cabanas; which did not emphasize price; and which was able to boast affluent customers who included Mrs. Andrew Carnegie, Marshall Field, and Ellery Sedgwick, editor of Atlantic Monthly.26

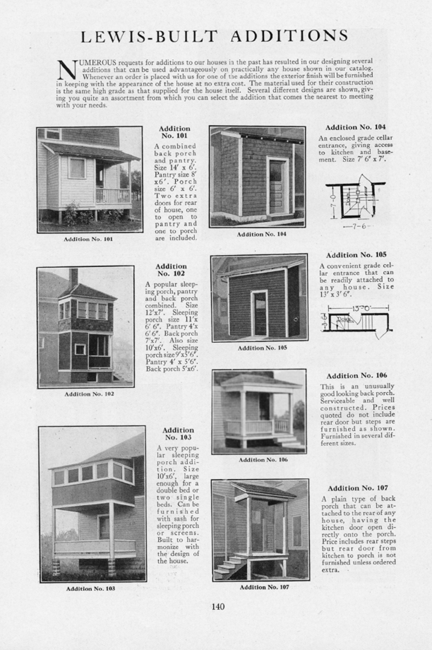

As business took off, however, most companies shifted their focus to the market for urban middle-class homes. Aladdin was a pioneer since Otto Sovereign, one of the founders, had a background in advertising. On April 5, 1909, Aladdin bought its first national advertising, half an inch in Collier’s, the Saturday Evening Post, and some Sunday magazines. Six years later Curtis, a pioneer of market research and publisher of the Post, used Aladdin to illustrate the power of advertising by itself placing a full-page advertisement in the Philadelphia Public Ledger. It spoke of “the business romance of a $1,500,000 industry which nine years ago did not exist,” implying that advertising had made it possible. By the 1920s, kits were firmly middle class. Pacific Ready-Cut, for example, which had begun by manufacturing one- and two-bedroom bungalows, moved up-market while Aladdin, and Sears, Roebuck played up the status of owning one of their homes, and so helped define a new middle-class norm. As expectations rose, some companies catered to a growing preference for minor additions (figure 11).27

Catalogs—those “silent salesmen”—were crucial. Daniel Boorstin has described these “farmers’ bibles” as “the first characteristically American kind of book.” His observations apply equally to the specialized catalogs that sold homes; at least five have been reprinted as Americana.28 Their rhetoric was florid, but practical. What made them effective was that, through artists’ sketches and photographs, they created vivid impressions of what houses looked like, while ground plans enabled buyers to imagine daily living. As a onetime kit salesman warned lumber dealers in 1931, the catalog “creates and suggests sales that you as merchants hesitate to put over.” It fed what was important not just for “woman-nature but human nature.” Although passive—the catalog sat on the coffee table, kitchen counter, or bookshelf—it was all the more effective, especially for women. Wives cared about, and were intimately involved in, the decision to buy a home. As retailers knew, they liked to shop before they bought: comparison, reflection, and multiple trips to the store were part of the process.29 The more valuable the sale, the more this was true, and no purchase was bigger than a house. A salesman with a quota, or accustomed to contractor customers, might hustle a woman—or a male home buyer, too—out of a sale. As one commentator noted in 1919, catalogs allowed the consumer “to slowly mak[e] up his mind . . . without being embarrassed by the presence and conduct of a salesman.” A book was always available to be picked up, set down, forgotten, but then revisited at the right moment. And to make sure that potential buyers did not forget, the mail-order companies kept track of who had requested a catalog, and then who had ordered. If the customer did not place an order, the company sent a reminder.30 It was an effective system.

Mail-order companies appealed explicitly to women. The major ones set up service departments. These designed houses, and also adapted plans (within reason) to suit buyers. Several gave advice on interiors, women’s special domain. In 1921 Aladdin offered a “Department of Service” for “the planning and arrangement of artistic exterior and interior effects”; Bennett organized a free interior decorating service to suggest color schemes, furnishings, and kitchen layouts; International Mill claimed to employ two women advisors and a home decorator who planned “from the woman’s viewpoint,” which meant “adding comforts and conveniences” and “perfecting the room arrangements” as well as “lessening the number of steps that the housewife must take each day in her work.” Sears simply claimed that their woman adviser “understands the requirements of the housewife.”31 Couples, not contractors, were the new target.

11. Kit additions. Only a couple of the larger kit manufacturers marketed additions: in the 1920s, home improvement was still a minor market. Source: Lewis Manufacturing Company, Homes of Character (Bay City, Mich.: Lewis Manufacturing Company, 1920).

Negotiating with Local Building Interests

While they addressed consumers, kit companies cared how the local building industry would respond. Like wholesalers of lumber, their main pitch was based on price, but the issue was never that simple. The first and most straightforward argument pointed to the efficiency of their large mill and commercial operations. Bennett’s catalog spoke of “gigantic, powerful machinery,” bulk buying, and “economy in drafting”; Gordon-Van Tine reproduced a picture of its “big gang trimmer” and boasted about its “door morticing machine”; Pacific kicked off its catalog with an illustration of a rafter saw that “does the work of 20 carpenters”; Sears, Roebuck displayed its seventeen-acre sash and door factory, the office of its Modern Homes Division, its window, door, and molding warehouses, and other mills in Illinois and New Jersey. Aladdin argued that its “rapid, automatic machinery” could do the work of a hundred carpenters, “and you get the benefit of this savings.”32 This sort of argument made sense to consumers, especially from the late 1910s. Skyscrapers, with vaguely analogous technology, expressed modernity, and Ford was demonstrating how effective mass production could be in bringing down costs, and prices.

A second line of argument was that, as Gordon-Van Tine put it, “by selling . . . direct to the user” the company “eliminat[ed] middlemen’s profits,” which meant the local retailer’s cut. This was an old argument, one that had sustained Granger sentiment in the 1870s. It had a point. Although lumberyards operated on slimmer profit margins than most retailers, their markup accounted for a quarter of the price to the consumer. As Aladdin noted, this “would typically add several hundred dollar profits to the goods you buy.” Of course, the price argument ignored the services that dealers provided, including credit, advice, storage, and just-in-time delivery to the building site, but at face value it sounded persuasive.33

Into the early 1920s, the kit companies’ case against middlemen could tap popular resentment against the lumber trade. The manufacturers who colluded to maintain prices, and the dealers who insisted that all lumber pass through their hands, had tarnished their industry’s public image. Arguably, it was the resultant “climate of suspicion and hostility” among farmers that gave mail-order companies their initial opportunity.34 That overstates the point, but popular sentiment did matter. The Lumber Trust was a sitting target. Mail-order companies encouraged the federal antitrust campaign and mobilized prejudices by enabling consumers make an end run around the trust’s local agents.

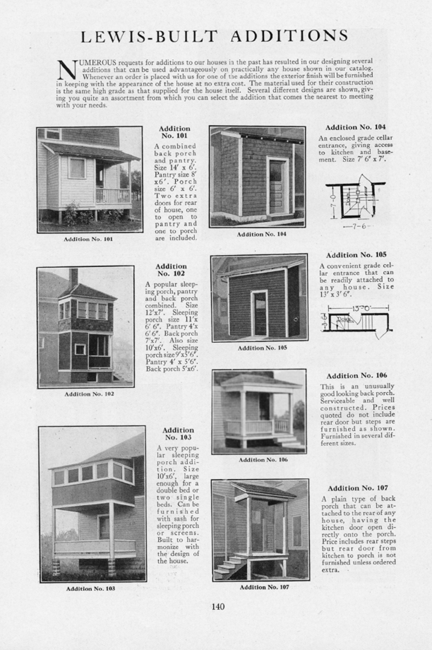

The moral argument against dealers was complicated, however, because local retailers could represent the mail-order companies themselves as bullies. Between 1905 and the early 1920s, small-town retailers mounted “trade-at-home” campaigns against mail-order concerns that employed no local people and paid no local taxes. In 1907, a new Home Trade League, based in the Monadnock Building in Chicago, claimed to speak for half a million midwestern retailers who “are fighting for their lives.” Such campaigning plateaued in the 1910s, when lumber dealers led many local campaigns. In 1917, for example, all dealers in Springfield, Illinois, joined the merchant’s association in a “brisk advertising campaign to promote the ‘trade-at-home’ idea.” One, Millrose Lumber, bought an advertisement listing “ten reasons why we should buy in Springfield” (figure 12). Wayne Fuller, the historian of Rural Free Delivery, has suggested that farmers remained skeptical of trade-at-home rhetoric: they liked catalogs for the choices they offered. But a significant current of support persisted. In 1919, for example, Butterick, publisher of The Delineator magazine and early sponsor of Better Homes in America, agreed not to take advertisements from mail-order concerns.35

Kit companies realized that they had to respond to trade-at-home arguments. Aladdin told its customers “when your dealer says ‘Don’t buy your lumber out of town,’ ask him where he buys the lumber he wants to sell you.” International Mill was emphatic: “The retail lumber man’s position is truly ridiculous. ‘Don’t buy lumber by mail,’ is his daily cry. But let him get short of ship-lap, shingles or lath or anything else and what does he do? He sits down in his office tonight, and orders a carload by mail. He does the very thing he tells you NOT to do.”36 This argument looked reasonable, but it ignored the services that dealers could provide, and the issue of local employment and taxes. At most, it made buyers feel more comfortable about sending their business out of town.

The kit companies pitched a third, and very important, argument about housing costs, but it had to be advanced cautiously. With the partial exception of the Canadian companies, Eaton’s and Hallidays, the companies shipped their lumber precut. Their catalogs pointed out that this saved the customer both materials and site labor: wastage was reduced and carpenters would spend less time measuring and trimming. Gordon-Van Tine claimed its kits reduced wastage by 17 percent, and Aladdin upped this to “at least 18 percent”; Gordon-Van Tine claimed reduced labor costs of 30 percent, Aladdin of 30–40 percent, and Montgomery Ward of 33–50 percent, while Sears, Roebuck reckoned that a scientific comparison (shown in a sequence of photographs) yielded a time saving for its Honor Bilt system of 40 percent. These claims were self-serving, but the kit companies had a point and customers knew it. In 1919, to industrial clients of “The Rodney,” a basic model, Aladdin stated that “a crew of twenty men should erect ten of these houses per week,” and added “they need not be skilled laborers.”37

12. Getting defensive. Because of their size, lumber dealers often led the local “trade-at-home campaigns” that merchants organized in many smaller urban centers during the 1910s in an attempt to repel mail-order competition. Source: A. W. Shaw, A Report on the Profitable Management of a Retail Lumber Business (Chicago: Shaw, 1918).

A customer could go one better by using the “simple, plain instructions and detailed blueprints of erection” that came with each package and literally build his own home. All of the major companies proclaimed this possibility, typically in association with the cheapest kits.38 This was an obvious way to extend their market downwards. In its regular catalog for 1919, for example, Aladdin claimed that “most owners of The Rodney did all the work themselves,” noting that two men could erect it in two days, while reporting that a satisfied buyer from Michigan had declared, “If a man is not a carpenter and wants to build his own house this is the only way.” The company’s Canadian catalog said the same thing, noting that a teacher from Bridgeburg, Ontario, had put up an Aladdin home by himself “with the help of one or two school boys on holidays.” Also in Canada, Hallidays included testimonials such as “my dad and I did most of the work on our house,” saving labor and $500 on materials. For a time, Gordon-Van Tine made a special appeal to “handymen.” In 1915, its building material catalog urged customers to “make your own window screens,” told them “how to lay, finish and keep a hardwood floor,” and claimed that “anyone can apply” their Mission Art Stain Finishes or their Kalsomine, an interior finish akin to paint. Illustrations showed housewives applying varnish and bath tub enamels.39

The owner-build option did away with the contractor. Even the conventionally erected kits threatened contractor’s and tradesmen’s incomes by reducing the hours needed to build a house and by undermining skills, which meant wages. This could be a problem, because kit companies and most buyers depended on contractors. Numerous and mobile, contractors were not in a good position to bargain: a skilled carpenter might decline a kit job, but another, less skilled or more desperate, could take his place. Even so, contractor refusals were a problem, especially in the 1910s. In response, Pacific Ready-Cut offered a construction service within the Los Angeles area. Buyers could take the free services of one of Pacific’s construction foreman, as long as he paid “carfare, room and board,” or they could pay extra for a house erected by one of the company’s own crews. Hodgson Company offered a similar service in the 1930s, offering to send a foreman to hire and train local laborers to bolt together the company’s panels. This complete building service was doubtless attractive to Hodgson’s customers, who were more affluent, but it was a marketing technique that most companies could not afford. Perhaps more significantly, because aspiring home owners viewed him as a source of advice, the contractor was in a good position to discourage kit sales, for example by badmouthing the quality of their lumber. The kit companies needed to keep contractors on their side.40

The companies addressed contractors through advertisements in trade journals such as American Carpenter and Builder, or through asides in the catalogs themselves. Their best argument was that kits made home buying more affordable, and so increased business. This would counterbalance the reduction in man hours per house. As International Mill pointed out in 1915, precutting raised the number of houses a carpenter could frame in a building season, from five to perhaps fifteen, the net effect being “almost as much benefit to you as to the general public.” Harris pitched bulk sales and, in a “page to the Carpenter,” it argued that their mills had done the “uninteresting” work, so that site labor could be carried out with “greater speed and pleasure.” Sears, Roebuck also targeted contractors. In 1913, it pointed out that by buying kits, contractors could erect several standardized homes, thereby raising efficiency and savings costs. It also included testimonials, and by the mid-1920s featured a page that reported “what contractors think of our Honor Bilt Ready Cut System”41. No surprises: builders reckoned that the materials were top-quality and that precutting saved time. The question, of course, was whether contractors would actually be able to find additional work to occupy the time saved by assembling a kit.

The kit companies tried other methods of persuasion. The simplest was to pay the contractors. Until the mid-1910s, companies recruited contractors as salesmen. Gordon-Van Tine offered 5 percent commissions for productive leads; other companies followed suit, and some reports suggest that “scalpers” gave kickbacks as high as 10 percent. Such incentives did double duty: they generated business and guaranteed contractor cooperation. But they cut into profits and were risky since they risked alienating buyers.42An alternative strategy was apparently used only by Sears, Roebuck. One difficulty the mail-order companies faced was their lack of local connections. In 1916, Sears had opened a local roofing office and in 1919 this idea was expanded to become the first sales office. The company then opened a succession in major urban centers—eleven by 1925, and forty-eight by 1930, by which time it employed 350 salesmen.43 All were east of the Mississippi, and many were in smaller urban centers such as Peoria (Illinois), Zanesville (Ohio), and even Peeksville (New York). Their purpose was to attract and serve buyers, but they also helped develop and cement ties with contractors. As early as 1927, “personal solicitation” by the eighteen to twenty employees who were based at its branches was generating most of the company’s business. Presumably, these employees spoke with tradesmen as well as potential buyers. Out-of-town contractors could visit the nearest Sears sales center when making a shopping trip or attending a trade convention. By 1930, Sears was offering to supervise construction of some of the homes it sold, presumably using local contractors.44

The one local building agent that kit companies ignored was the architect. They touted their architectural and design services and plausibly claimed, as Lewis Manufacturing did, that their services produced better plans than the average contractor could “from a plan of his own making.” Indeed they suggested that, because of their scale of operations, each functioned as a “clearing house of building ideas.” But none compared their designs with those of architects. They might not have won such a comparison, but that was beside the point. With few exceptions, those who bought kits were not in the market for the services of an architect. The kit companies knew who had to be placated and who could safely be ignored.45

Dealers React

In the kit manufacturer the dealers had discovered a new threat. They responded in two ways. Negatively, they attacked them in every way they could; positively, they reorganized to meet them on their own terms. They were always willing to consider either option, but the balance was to shift in 1914.

The lumber retailers’ first instinct was to lash out. They had joined forces before to attack companies that sold direct, so why not again? Since the kit companies appealed directly to consumers, the retailers needed a new approach. One method was to persuade customers to join a boycott by exploiting trade-at-home sentiment. The trade press eagerly reported such activity. In 1914, for example, the Western Retail Lumberman reprinted one woman’s letter that read, in part, “I do not know of any merchants in the small towns of Kansas who are making unreasonable amounts of money . . . Montgomery Ward on the other hand is a multimillionaire.” She concluded: “Who are getting the big profits?”46 Such anecdotes gave dealers ammunition to used on skeptical customers.

When all else failed, dealers could harass and calumnize. A favored method was spamming: inundating a kit company with requests for detailed specifications on the bill of goods that would be shipped for a particular order. In 1912, American Lumberman announced a competition for ideas about how to meet the mail-order competition. Declaring it would not consider “espionage, bribery or . . . surreptitious methods,” it nevertheless allowed the use of fictitious names to prevent reprisals. With heavy wit, the trade press referred to mail-order companies generically as Montgomery Sawbuck—because they chiseled! Even in print, language became heated. One concern was damned for its “contemptible and dishonorable” advertising, and for a supposed tactic of plying customers with alcoholic drinks.47

Lumber concerns also tried industrial espionage. The polite version was to gather information about how mail-order companies operated. Some retailers collected catalogs. Trade journals advised others to check the package of materials that arrived at the depot. Freight rates varied with the grade of lumber, and dealers knew that some companies included millwork in shipments of common stock.48 Beyond this, trade associations paid investigators to track down the mail-order companies’ suppliers so that they could be boycotted.

The mail-order companies responded by pushing federal authorities to take the dealers’ associations to court. In 1911, fourteen association secretaries were charged with exercising a “trust of power” by maintaining a blacklist in order “to put a complete stop to the direct sale of lumber by wholesalers to consumers.” Their Lumber Secretaries’ Bureau of Information maintained a blacklist that included the names of more than a hundred “mail-order houses and wholesalers from Pennsylvania to the Pacific coast.” Another suit followed, against Michigan dealers who had “most specifically opposed” the mail-order companies. Another suit included “sensational charges” against the “Lumber Trust” that “dominates the lumber trade of at least twenty states by maintaining a spy system, blacklists, divisions of territory, and other alleged illegal methods” via a “central agency in Chicago,” the Bureau of Information.49 Some suits were dropped, but the Lumber Secretaries, together with the Mississippi Valley Lumberman, were found guilty. In the end, the most significant case concerned the Eastern States Lumber Dealers Association, also for a blacklist. This became a landmark when charges were upheld by the Supreme Court in June 1914.50 Blacklists had been blacklisted.

The lumber industry was also losing in the court of public opinion. Gordon-Van Tine’s building catalog included a customer’s letter from Peavey (Id.), which reported that a local retailer had claimed that “the lumber trust or association, or some sort of combination” had put Gordon-Van Tine out of business. “I do hope not,” the correspondent grumbled, “lumber dealers have a great graft in this new country.” In April 1914, the Department of Commerce published a major report on the lumber trade. The findings were damning: the commissioner of corporations, Joseph E. Davies, commented that the trade’s “activities in fixing prices and in restricting output have profited the lumbermen at the expense of the consumer.” The findings were directed at manufacturers and wholesalers, but in September 1914 yet another suit was brought against dealers, this time the Northwestern Lumbermen’s Association and the MVL. The MVL itself noted that politicians and mail-order companies had created a “public sentiment . . . against those identified with the lumber industry.”51

Something had to change. The first to acknowledge this was Platt B. Walker. Walker was secretary of the Western Retail Lumbermen’s Association and one of those charged in 1911. Early in 1915, as editor of the Western Retail Lumberman, he noted that mail-order companies had mobilized “public sentiment,” but then turned to the question as to what dealers should now do. He argued that the best answer was to “give the customer the option of buying the same material on the same terms and conditions offered by the commercial pirates.”52 A decade earlier, this call would simply have meant a renewed commitment to keep prices low. In the emerging kit era, it meant much more.

A New Public Face, 1914–1929

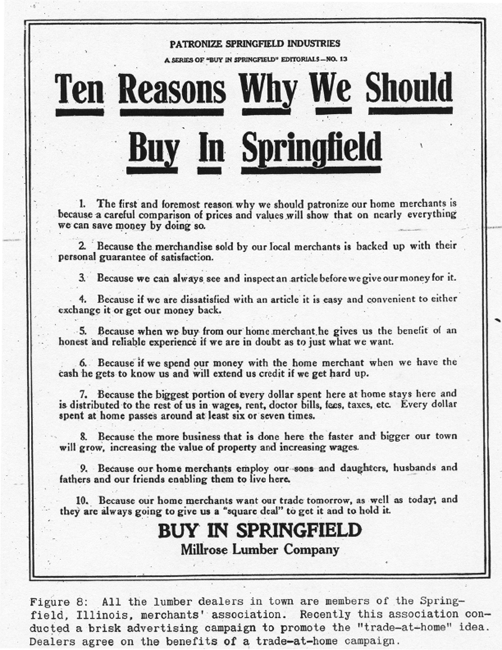

Platt Walker, and soon other trade leaders, concluded that dealers could thrive only if they adopted “modern merchandising methods.” This meant changing what they offered, and how they offered it. Informing everything had to be a new commitment to identify, and meet the needs of, the consumer.53 It followed that associations and trade journals should promote a reorientation of the dealer’s operations. To some extent, they already had. In May 1914, C. H. Ketridge, the veteran lumberman who wrote the MVL’s “Realm of the Retailer” column, noted that lately associations had begun to offer their members more services. These included advertising ideas, legal advice (notably about mechanics liens, a constant aggravation), and in general the application of “scientific principles of business.” Because of the Supreme Court’s decision in June, the pace of change quickened greatly from 1914. Because they had had their knuckles so publicly rapped, the MVL and Platt Walker became lead advocates of the new thinking. In September 1914, the MVL reported that Walker was now arguing that his association must turn away from “protection” and instead “furnish[] each . . . member those legal associational and industrial services which . . . will enable him to conduct his business first, to the benefit of the consumer and, second, to produce a greater net revenue for the business.” The implication was that dealers should think of themselves as retailers first, and lumbermen second. By the end of the year, Walker had redefined his readership: his journal’s masthead now addressed “Professional Retail Building Material Merchants,” while, for the Western Retail Lumberman, A. L. Porter fashioned a prescient image of the future, the diversified retailer (figure 13). Little did he know how far in the future his ideal would be realized.54

13. The vision. Framed by the ideas of A. L. Porter, this artist’s image of the ideal, diversified, and consumer-oriented retailer, would not be widely realized until after 1945. Source: Western Retail Lumberman 4, no. 10 (December 16, 1915): 8–9.

Soon, all-purpose retailers were able to subscribe to a new journal, Building Supply News. This was launched in 1917 by Harold Rosenberg, inevitably in the Midwest (specifically Chicago). Rosenberg declared BSN to be “a vigorous champion of the interests of the building material dealer-distributor.” He was willing to offend, and lose the advertising of, some manufacturers, and forty years later he claimed that for this he was at first “ridiculed” by Elmer Hole, then editor of the American Lumberman. There may be an element of myth-making here, but a midwestern dealer agreed that Rosenberg had indeed created a trade journal for a new type of retailer. BSN could not cater to the new breed, for these hardly existed, but instead worked to bring it into existence. Every issue featured a retailer who was adopting progressive practices. Judging from those it selected, its readership—or intended readership—included some hardware stores as well as lumberyards. In 1927, for example, it featured the Scarsdale Supply Co., a hardware store that was so diversified that it was almost a department store. Located on a main street, it contained “every conceivable article,” including paints, furnishings, appliances, radios, and even toys, as well as hard-core building supplies, these being located in eleven departments distributed across 4,500 square feet of space. BSN also claimed to express the interests of “the consumer where they conflicted with those of readers,” though this was rhetorical since, in Rosenberg’s view, those interests were synonymous: retailers should stock and do whatever was profitable, that is, whatever the consumer was willing to pay for. The idea of the all-purpose building supply retailer, local but modern, now had an effective champion.55

It was also the competition from kit companies that prompted dealers to form their first national organization. In 1911, the WRL reported that a group of retailers were forming a national body, but nothing came of this. It was five years later that several big-city dealers established the National Retail Lumber Dealers Association. Its role was positive. It promoted communication among the regional groups, and enabled dealers to influence public opinion. By the 1930s, it was affecting federal policy. Indeed, a past president, Norman Mason, was made administrator of the Federal Housing Administration. Even in the short run, it had an effect. By 1923, according to Nelson Brown, it had become “one of the most influential and progressive of the national organizations in this country.” It lobbied the regional and national associations of manufacturers to promote the better marketing of lumber, and threw its weight behind the nationwide Own Your Own Home campaign. As a result, dealers became and remained better organized than manufacturers or their contractor customers. In 1940, there were thirty-six organizations of retailers. Of these, 83 percent (30) could claim membership rates of 40 percent or better. This may not sound impressive, but it was better than the organizations of building suppliers, among whom only 64 percent (77 of 121) achieved the 40 percent membership threshold, and far better than contractors, among whom the equivalent proportion was only 25 percent (3 of 12). In an ill-organized industry, dealers were the interest group that spoke with the most coherent voice.56

A new national organization was helpful, but above all the kit competition had to be met at the local level. The new retailer would have to present himself better, and more often, to the public. In 1914, Ketridge argued that the kit companies’ growth depended on smart advertising. This became the standard view. In 1931, Charles Fish, an ex-salesman for a mail-order company, recalled an experience that he viewed as symbolic. He had called on a potential customer only to discover that the local lumber dealer had preceded him by a few minutes. The farmer would not let the dealer across the threshold, but when he learned who Fish represented he waved him in. Advertising opened doors, and lumber dealers were sometimes coerced into discovering its power. When a Seattle-based concern began advertising in local newspapers, one editor approached the local retailer with the proposition that he would refuse to take the mail-order company’s check if the dealer promised to buy space instead.57 This quid pro quo was probably agreed in other places too, but it was not usually necessary. The trade press debated whether advertising was more important for city yards, which had many nearby competitors, or for small town dealers, who enjoyed a local monopoly but who made a higher proportion of their sales to consumers.58 But they agreed that dealers should advertise more, because they were tucked away near freight yards and away from street traffic.59

Dealers began to get the message. In 1918, Shaw’s survey found a new commitment to advertising. He cited Thompson Yards, which had started a “snappy little house organ” named “Upper Cuts,” which aimed at “Making the Fir Fly.” For the next decade, when they spoke about how to meet the mail-order threat, as A. D. F. Campbell (Arnprior, Ontario) did at the Ontario Retail Lumberman’s Association annual meetings in Toronto in 1927, dealers put better advertising at the top of the list.60 By then, the point was taken for granted. Fred Ludwig told his Yale audience that, given the lack of national advertising of lumber, dealers must invest 1½–2½ percent of annual sales in local promotion.61 The norm was probably one-fifth that amount.

The challenge was that, unaided, dealers could not match the kit company’s copy. As Ketridge commented, “Many a dealer would change his ads more if he knew how to write them.” Here was where trade associations and journals could help. In 1913, the Northwestern Association established a service department that helped dealers write ads, and other groups did the same, especially in the western and midwestern states, and on both sides of the border. The most creative scheme was launched by W. Wadsworth Wood in 1925, when he founded the Progressive Merchants Bureau in New York City. His bureau offered a consulting service to dealers and associations. Wood persuaded Lumber (Manufacturer and Dealer) to launch an advertising service department through which he offered advice. The unique angle was that dealers were encouraged to submit samples of their advertising for Wood’s critique. His commentaries, polite but penetrating, used these examples to illustrate his pet themes: include human figures in illustrations; emphasize the use, not the product; appeal to emotions; don’t be negative about competitors; do not hint at the negative qualities of any building materials. Stated baldly such generalizations may have sounded abstract, but Wood’s specific suggestions brought them home.62

One point that Wood, and other commentators, emphasized was that dealers should not advertise individual items: lumber, shingles, and mill-work; wallboard, cement, and flashing; pipes, screws, and wire. Still less should they wax eloquent about their grade of shiplap. Did the automobile companies exalt tailpipes and shock absorbers? No: they spoke of convenience, reliability, and speed. Dealers were told to follow suit by promoting the whole house. As Platt Walker declared rather bombastically in 1915, advertise “something in which the customer was INTERESTED . . . A HOUSE.”63 And not just a house, but a home: a safe investment, a place of comfort and security in which to raise a family.

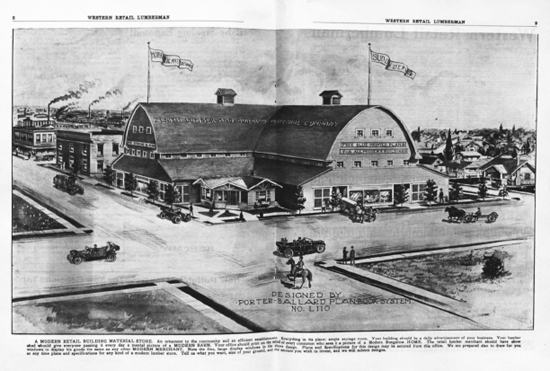

Through their catalogs, mail-order companies had taken the advertising of homes to a high art. Dealers responded, in effect, by offering their own catalogs. At first, this meant carrying plan books. Soon, major trade journals and dealer associations began to offer plan services for their subscribers and members. An early scheme was the Porter-Ballard system, advertised by the Western Retail Lumberman in 1914. Dealers paid $50, which entitled them to receive a set (catalog) from which they could order up to fifty free plans and specifications. They could also use the association’s “trade-pulling advertising.” Within a year, 524 sets and 2,300 plans were sold in twenty-eight states, as well as Canada (and Australia!). The association for western Canadian dealers also ran a plan service.64 By 1919, 10 percent of independent dealers across the continent had signed on for a plan book system. The proportion would have been much higher among the line yards. Where line yards were common, notably western Canada, most dealers had ready access to a plan service by 1915.65

By the mid-1920s, many dealers used some sort of plan service. Some dealer groups, such as the Michigan association, assembled plan books. Alternatively, trade journals featured a house in each issue and invited dealers to purchase the plans for those that appealed. The American Lumberman and Building Supply News both did this. Catalogs were also sold to dealers by manufacturers of millwork or lumber, such as Bilt-Well and Weyerhaeuser, and by regional associations of producers, of which the southern pine was again the most progressive. Some plan services let the dealer to put his own name on the front page.66 A few architects looked askance, but there was little actual competition between them and the dealers. Architects designed fewer than 10 percent of all new homes in this period, and most of these were expensive. Few were troubled by the dealers or the kit companies, who targeted the more substantial middle and lower-middle segments of the market.67

Dealers also tried to rally the local building industry. Some commentators, notably Arthur Hood, argued that to respond to mail-order competition, “all factors of the building industry [should] unite in a community program,” ideally with the dealer at the center. It was easy to get contractors on board since they felt threatened by the kit business and depended on the retailer for credit. Lenders also listened, not least because dealers often sat on their boards of directors, as members of the Mueller family did in Davenport, Ia. Such connections mattered when kit purchases were secured on a banker’s note. Attacking this option, in 1914 the Mississippi Valley Lumberman suggested that each dealer should have “a frank talk with his local banker” to discourage their cooperation with the kit companies. This strategy would not have worked in Davenport, home to Gordon-Van Tine, which doubtless had its own local connections, but elsewhere might have borne fruit. Newspapermen were perhaps the most difficult locals to persuade, depending on local sentiment: unlike the mail-order concerns, dealers were did not spend a lot on advertising.68

Most of all, to push themselves to the fore, dealers would have to present a better face to the public. As the WRL observed in 1915, “Your building should be a daily advertisement of your business.” This meant presenting an attractive facade; cleaning up and covering over the lumber sheds; installing displays; and employing helpful staff. Ideally, displays would be arranged in a purpose-built showroom, with a separate space where customers could sit and consult catalogs. It was a question of meeting the expectations that kit companies had created. In 1927, BSN reported that Montgomery Ward was opening sales centers with “the most modern display rooms it is possible to build.” For dealers to respond, it editorialized, “adequate display rooms are essential. Up-to-date merchandising methods must be adopted.” All the trade journals showed what “progressive” dealers were doing. In 1919, for example, AL discussed the “modern building material store” that William Cameron of Fort Worth, Texas, was currently building. Some argued that dealers should speak of “stores” rather than “yards.” Dealers responded cautiously. Some dolled-up their yard to wow the uncritical customer, but a new showroom was another matter, and relocation was more or less out of the question.69

A cheaper, but still not an easy, stratagem was to retrain or replace staff. This happened first in the line yards. As early as 1915, Platt Walker reported that the general manager of a major western line yard was thinking about replacing his more conservative yard managers, while the auditor at another said that his company was now training young men about the new sales techniques. Change came more slowly in the individually run businesses, whose owners lacked both the skills and the resources to retrain staff and who balked at replacing a family member in the yard. Here again, associations came to their assistance by offering training schools, though few took advantage of this service before the Depression; usually, change happened when a dealer retired.70

Merchandizing: Prices, “Lines,” and the Package

No matter their public face, the basic idea was to offer competitive prices. The trade press claimed that local retailers could compete with mail-order prices, and illustrated the point, although in correspondence dealers sometimes expressed doubts. In 1919, for example, the AL reported that advertising for Simpson Lumber, of Washington, Indiana, compared their prices with those of a mail-order company that had been soliciting in the area.71 Unfortunately, price comparisons were complicated by the diversity of grades and types of lumber, and were trickier still for kits. For consumers, the meaningful comparison was on a bill of materials, which included lumber of varying grades and dimensions, hardware, electrical and plumbing supplies, and perhaps a furnace. No dealer could offer, or price, an exact replica. Local retailers needed to persuade consumers that their charges were reasonable, but prices alone could not be decisive.72

What really mattered was service. The point was made many times.73 It also had many aspects. It should include a plan service that went beyond the catalog so as to help “Mr. Man’s wife decid[e] which house Mr. Man likes best.” It could also include the provision of credit. As Floyd Reynolds of Burr Lumber (Gloversville, New York) commented: “The large mail order houses are offering all sorts of financing for home builders. The dealers will have to meet this.” Those that had close connections with local lenders could do this. Wilson and Greene Lumber in Syracuse, for example, even allowed owners to count sweat equity towards a down payment. But, as noted in the previous chapter, few dealers could do much about the problem, especially for home improvements. By the end of the decade, some concluded that purely local strategies were insufficient. In 1930, Arthur Hood founded a national finance corporation, whose prime goal was to meet the mail-order competition. Unfortunately, the timing was poor and its impact limited. On the credit front, during the 1920s, few dealers could offer much.74

What dealers could do, and did, was stock a widening range of lines. By the 1920s, led by upstart BSN, trade journals carried stories of dealers in places as diverse as Rockford (Illinois), Birmingham (Alabama), San Antonio, and Chicago who had successfully diversified. They featured claims by prominent dealers, such as Julius Seidel of St. Louis, that “dealers can be department stores in building materials.” This had an effect. As early as 1912, an Alberta line-yard chain claimed that “everything is carried in the building line.” Others followed suit. In 1927, a Long-Bell manual insisted that “managers should use every effort to prevent [the] spread” of mail-order competition by “show[ing] their customers the advantages of trading at home.” These advantages included being able to examine goods before buying, to return unwanted goods (“if in good condition”), make exchanges, or buy additional materials at the same price. To realize these advantages, dealers carried a wide range of materials. A survey found that in Kansas, prime territory for Long-Bell, lumber’s share of total sales had dropped to 65 percent and was falling. This was typical. Speaking at Yale, Ludwig identified the diversification of lines as the main recent trend in the business.75 It did not occur overnight, but change was happening.

Some foresaw the logical outcome. As early as 1919, the AL reported A. L. Porter’s opinion that “a new era of merchandising of all building materials is upon us,” together with his prediction that the consumer would buy all building materials from “one bang-up modern merchandising institution in his town.” By the 1920s, pushed by BSN and the WRL, trade journals promoted the idea of merchandizing, that is, stocking whatever consumers needed. They reported local retailers, from Milton (Oregon) to Chicago and Boston, who were selling “the complete house.” In Carlinville (Illinois), the local yard rose to Sears, Roebuck’s challenge by entering into “all the activities of building homes.” Even—or perhaps especially—where there was an unprecedented cluster of kit homes, a local dealer reorganized to outdo the competition. BSN reported that in San Antonio, Steves and Sons were copying “the cracker people” by selling the package. More to the point, Arthur Hood claimed that “the most successful merchandisers . . . appear to be those who are selling the most complete line.” Others agreed. Before the 1927 retail convention season, AL distributed a questionnaire on thirty-two issues. One asked “is the time coming when [the] retailer must sell the complete home?” Most respondents said yes, some forcefully. In published replies, several mentioned the pressure of mail-order competition. In the 1920s, we can even see the beginnings of the all-purpose building supply store. Not a lumber dealer like Dix, or a hardware store like the Scarsdale Supply Co., that had diversified, but a retailer who destroyed categories. Featured by BSN in 1927, the Smith-Green Co. in Worcester, Massachusetts, was a good example. Described as a “building supply firm,” Smith-Green had a fifty-foot frontage on a main street, with display windows “to catch the feminine interest.” In that spirit, it encouraged “shopping” as well as “purchasing.”76 Kit companies had triggered a slow-motion landslide

Informing all these initiatives—the improved public face, the plan catalogs and services, diversification, and house packages—was the assumption that dealers must target the consumer. Contractors, of course, should not be neglected. In large centers, they were the main customers, but even here some argued that the important person was the owner since, as J. Earl Brightbill said to Virginia dealers, he was “the man who pays the bills.” This shift in focus was the key. As early as 1914, when A. L. Porter revised his thinking about the trade, he altered his journal’s motto—“Help One Another”—by adding “to Help the Consumer Buy.” By the 1920s, the shift was happening. Brightbill claimed that at his yard in Hummelstown (Pennsylvania), between 1925 and 1927, sales to buyers, as opposed to contractors, jumped from 39 percent to 49 percent. This shift was a straw in the wind.77

Among the new customers was a sprinkling of women. In 1919, the American Lumberman claimed that had become a “cliché” to speak of the increase in women customers. But the increase was from a tiny base and did not amount to much. During the 1920s, trade journals reported some retailers who were going out of their way to attract women. In 1927 alone, for example, it noted that Harris Lumber of Loveland, Colorado, had organized a “ladies day,” an open house with special displays, and then how Hines Lumber of El Paso had run a competition for two women’s clubs to see which could get more members to visit the yard. Including a competition for best kitchen plan, Hines stimulated two thousand visits in six weeks, pushing up sales by $100 a day. More permanent yard improvements were necessary to get repeat sales. Speaking to the Southeast Missouri Lumbermen’s Association in 1933, J. G. Good of Swanson Lumber of Doniplan, Missouri, reported a recent conversation with a woman acquaintance. “She said ‘a number of years ago I went with father to a lumber yard but came away disgusted. The office was dingy and dirty, cigar and cigarette stubs lying on the floor, several loafers sitting by the stove, and the air blue with smoke, so I had no desire to go there again.’” But, according to Mr. Good, on a recent visit to a lumber dealer she had been impressed by a “friendly greeting” and by the “large, clean, nicely painted and decorated” office, with its “assortment of different articles for sale.” Generalizing, she supposed that the dingy yard of yesteryear was being replaced by “‘a bright, peppy, cheery successor—the building material store.” Not so fast. For every store like Dix Lumber, Scarsdale Supply, or Smith-Green that attracted a stream of women, there were ten like Harris Lumber of Loveland, or Hines Lumber of El Paso, that for most of the year saw only a steady trickle, and twenty or more who experienced nothing more than a drip . . . drip . . . drip.78

But drips and trickles accumulate. Between 1914 and 1927, the lumber retailer had come far. Dealers were beginning to think positively, and trade journals set the tone. By 1919, the “Realm” columnist in AL conceded that kit companies had “unintentionally forced us into the straight and narrow path of progress more than once,” while Ketridge, writing in the MVL, reckoned that dealers owed them a debt for showing how “aggressiveness” could create business.79 Facetiously, AL’s columnist proposed that the trade should endow them with “a maintenance fund in order that they might continue to teach us.” Ketridge learned to eat his words. When Sears, especially, opened attractive home centers that solicited local business, he found the prospect daunting: “the picture was not pleasant.”80 But there was no reversion to the defensive tactics of the prewar era. The trade press continued to report each kit company initiative—easier financing, model homes, and so forth—but their accounts were (mostly) fair, and came with suggestions as to how dealers should respond, for example by building display rooms, using personal contacts, or working to keep contractors loyal.81

The lumber dealers’ response had become positive, and specific. When American Lumberman polled readers before the 1927 convention season it reported that the 500 dealers who replied ranked mail-order competition twenty-fourth on their list of priorities, higher in some midwestern states, for example Illinois (15th). The kit competition still mattered, but the threat had been broken down into its component parts. Dealers now believed that, apart from perennial questions such as how to hold down costs (1st) and generate sales (5th), the leading issues for discussion included yard appearance (2nd), the handling of women customers (7th), and selling complete homes (12th). These were all issues that mail-order companies had put on the agenda. Instead of damning (or ignoring) the source of their problems, dealers now focused on meeting each challenge. A writer for Printer’s Ink, the leading journal for advertisers, made the point by overstating it. In 1931 he claimed that the kit companies had goaded lumber dealers into “thoroughly modernized and effective merchandising.” Most dealers still did not fit that description, but he was right in identifying the force that had goaded them to rethink their business.82 Retailers were finally beginning to think about the consumer.