NINE

Mr. and Mrs. Builder

In spring 1948, a young family man from Manhattan decided to make a place for himself in the country. He found the ideal wooded site and framed a cabin. It was, he recalled, a rewarding experience. “When I closed in the roof it was a miracle,” he declared, “as though I had mastered the rain and cooled the sun.” He could have afforded a carpenter, but “for reasons I still do not understand it had to be my own hands that gave it form, on this ground, with a floor that I had made.” Then and there, while “the bag of nails were still stashed in a corner with my tools,” Arthur Miller began writing act 1 of Death of a Salesman.1

In Salesman, Miller told the story of a man, Willy Loman, who makes a living in sales, but who finds fulfillment tinkering with tools. As Biff, Willy’s son, declares wistfully, “There were a lot of nice days. When he’d come home from a trip; or on Sundays, making the stoop; finishing the cellar; putting on the new porch, when he built the extra bathroom; and put up the garage.” Speaking to Willy’s old friend, Biff concludes: “You know something, Charley, there’s more of him in that front stoop than in all the sales he ever made.” Charley agrees: “Yeah. He was a happy man with a batch of cement.” Willy knew it. He had already boasted that “all the cement, the lumber, the reconstruction I put in this house. There ain’t a crack to be found in it any more.” And this domestic labor was part of Willy’s vision for the future: “we’re gonna get a little place in the country, and I’ll raise some vegetables, a couple of chickens.” Once there, since “I got so many fine tools, all I’d need would be a little lumber and,” hopefully, “some peace of mind.” For Willy this was a social statement. “A man who can’t handle tools,” he insisted, “is not a man.”2

With less skill but greater effect than Arthur Miller, another writer had already expressed strong views on the man’s role in making and maintaining a home. Paul Corey grew up on an Iowa farm, and during the Depression built two homes in succession in rural Putnam County, New York State. He aligned himself with a homestead movement, which he refurbished for the postwar veteran. In Buy an Acre (1944), Corey told veterans that soon “the country around about our cities for a radius of from fifty to one hundred miles will become the New Frontier of America.” There, he predicted, “ten million tiny homesteads will spring up within commuting distance of factory and business.” On one-acre lots these would not support self-sufficient living. Instead, this “Second Frontier” would be “the average family’s way out of our looming postwar difficulties.” For Corey, this option was to be welcomed by the average American, “working at some routine job in order to enjoy your home and living.” For such men, “your real job is your home,” and this meant more than just buying a place and enjoying it. As Corey put it, in a detailed account published two years later, “If you haven’t that basic desire in life—the desire to build your own home, then there’s something wrong with you.” Here, again, was an assertion of masculine pride and resourcefulness.3

Arthur Miller and Paul Corey were articulating a new outlook. In part, it had anti-urban roots, of the kind articulated contemporaneously by Conrad Meinicke in Your Cabin in the Woods (1945). It also appealed to an American tradition of self-reliance, which had recently been reinforced by the Depression experience of self-provisioning. It had a strong individualistic element. For Corey, this meant flouting convention. Don’t be deterred by those who look down their noses at you for building from scratch, he insisted. Ignore “the good lady [who] always won the first prize at the local flower show” and who views “your little shack . . . as a monstrous blot on the landscape.” He was not conjuring a straw woman. From the better side of the tracks, the fumbling of builders like Corey raised concerns. In 1946, Eric Hodgins wrote a story, soon celebrated in film, about Mr. Blandings, a Madison Avenue executive who had a house built in exurban New York, with the benefit of contractor and architect. At one point, Mrs. Blandings becomes distressed when she discovers that a stonemason neighbor is building a “horrid, nasty little house with two rooms and a porch” just half a mile away, a “beastly little bungalow” with a “tarpaper roof” where his wife keeps goats. “I could simply weep,” she exclaims. Corey himself had dealt with neighbors like the Blandingses, and reports with a growl, “I brooded over their attitude for months—like hell I did.”4

Miller made Willy Loman, who so much wanted to be liked, embody a gentler and more urban version of the can-do spirit. His was not so much a rejection of the urban way of life as a coming to terms with it: being handy showed that the man had not been completely tamed. In the postwar suburbs, this more than anything became the dominant structure of feeling. In his collective biography of a postwar Jewish family, Donald Katz speaks about the way his father moved from the Bronx to buy a home on Long Island in 1952, where he immediately set about improving it. Soon, prospective buyers visiting the area stopped by: they “were regularly brought . . . to see what a homeowner could do with old-fashioned, all-American knowhow and the will to personalize a simple, straightforward structure through the agency of his own hands.” As an almost mandatory gesture of masculinity, being handy was not uniquely American. Speaking about Canada in the same period, Ian Brown has commented that “the shame of not being handy was a secret plague.”5 It was becoming an expectation that the suburban father should be able to prove himself by building, or at least improving, his home. Coupled with the housing shortage to which Corey referred, and encouraged by the media and building suppliers, this view informed an unprecedented boom in owner-building after 1945. In turn, it enabled a wave of do-it-yourself to lead the emergence of the modern home improvement phenomenon.

The Housing Shortage

Paul Corey’s vision of a “Second Frontier” at the exurban fringe was prescient. By 1949, a third of all new houses, and a quarter of all dwellings of any kind, were being built by owners for their own use, often well beyond city limits. This boom varied from place to place, of course, and by region. The incidence of owner-building ranged from lows of 3 percent of new single-family homes around Dallas and Washington, D.C., and 8 percent in New York, to much higher levels around Pittsburgh (21 percent), Boston (24 percent), and Seattle (29 percent). It was twice as common in the west as in the south; three times more prevalent in nonmetropolitan (62 percent) than in metro areas (19 percent). Around Peoria it reached about 70 percent; in rural North Carolina perhaps 96 percent. No city, town, or suburb, and certainly no unincorporated district, was unaffected. The amateur builder was a national phenomenon.6

Indeed, the amateur boom was international. In Canada, contemporaries spoke of whole suburbs being developed by amateurs after 1945, including much of Montreal’s south shore and several suburbs to the northwest and northeast of Toronto. One writer claimed that all “owners of moderately-priced homes are essentially do-it-yourselfers.” Oral history interviews show that homesteading was happening from coast to coast, in clustered developments and scattered locations. Australian media and statistics show that, Down Under, thousand of Corey-style “battlers” created the same trend. There, the proportion of new homes that were owner-built rose from the late 1940s, peaking at about two-fifths in 1954.7

Hardly anyone saw the amateur boom coming, least of all those who were soon to make it. In late 1944 and early 1945, Architectural Forum carried out a national survey of American 8,052 men and women, the sample being weighted for “geographical, economic and cultural factors.” Over two-thirds of respondents reckoned that owning was better than renting, and of those deemed “good prospects” of becoming owners, two-thirds expected to build a custom house rather than to buy. Asked what they would do if rising costs made this impossible, most said they would lower their expectations, wait, borrow more, save more, or give up. None mentioned the possibility of building their own.8

Experts shared that mindset. During the 1920s, community builders had taken a growing share of the new home market, and from 1934, the federal government had encouraged them. Even so, most observers assumed that building on contract would remain significant. When building revived in the late 1930s, Better Homes and Gardens offered New Ideas for Building Your Home, while Frazier Peters advised prospective owners who planned to hire a contractor how they might manage Without Benefit of Architect (1937). After World War II, a series of guides offered similar advice. In 1945, a group of architects weighed whether it was better to build or buy (you can predict their preference). In 1946, Elizabeth Mock addressed those who had chosen to build; Howard Morris advised how they might do it better; and Harold Group offered a selection of options based on plans distributed by a House-of-the-Month Club. None suggested that prospective home owners might build their own, though Johnstone and associates did comment that “the great majority of contractors” are “skilled craftsmen who derive a sincere pleasure from doing work of good quality,” arguably damning with faint praise. By 1947, however, the owner-build option could not be ignored. Together with Douglas Tuomey, Kenneth Duncan, associate editor of the Savings Bank Journal, tackled it head on in a Primer for Home Builders. “The purpose of this book is not to teach the homeseeker how to build his own house with his own hands,” they cautioned, because “trades must be learned the hard way—by experience.”9

The building trade press agreed, though most writers reckoned that owner-builders expanded the market for homes rather than competing with professionals. In the Home Builders Monthly, James Pearson inveighed against publishers who were beginning to encourage owner-builders. Lenders, he pointed out, looked skeptically at the amateur, adding that “skilled builders know what types of materials to buy. Amateurs do not.” Amateurs would pay more for materials because they buy in small quantities; they lack experience in scheduling tasks and coordinating orders for materials; those employing subcontractors do not know how to handle bids. All in all, Pearson concluded, owner-building was a bad idea. The National Association of Home Builders had already made the same case, as was widely reported in both Canada and the United States. But early on, the trade journals of retail suppliers took a different line. By June 1946, the American Lumberman had detected the nascent boom in owner-building and urged “alert” dealers to support it, a view it soon repeated. Dealers were the one group that had little stake in who built, as long as building got done.10

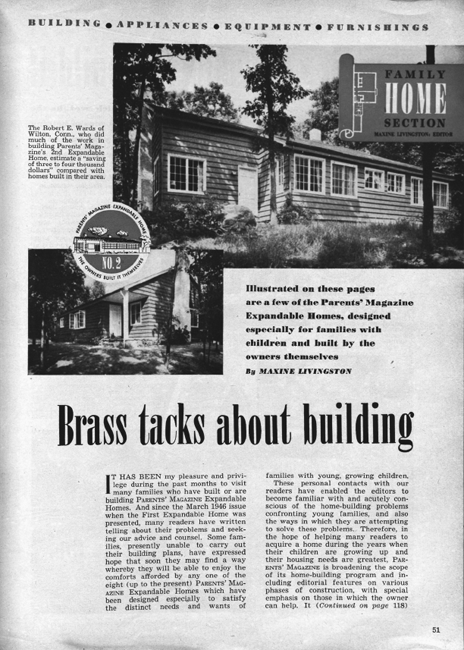

Consumer publications such as Parents Magazine were also slow to see the amateur boom. Founded in 1926 with Rockefeller Foundation money, PM thrived, and by 1950 boasted a circulation of about a million, probably better-educated men and women. It had an educational mandate that included housing since the editor, Clara Littledale, believed this “affected children,” the ultimate concern. For those reasons, PM provides a litmus test of middle-class attitudes. Looking ahead to war’s end, in January 1945 it urged readers with “enough money” to “plan now” to hire an architect and build a home. As costs rose, a survey soon showed that readers were willing to make compromises, and PM commissioned and published designs for a series of “expandable homes” to be built in stages as finances and family size might dictate. For three more years, the editors assumed that interested readers would hire contractors. By 1949, this had become untenable (figure 34). Readers’ letters and editorial inquiries to those who had built one of the expandable homes made PM ”acutely conscious” of the problems home builders faced. In February it told about one family that had built, almost from scratch, its Second Expandable Home, including the wife’s comment that “it is simply beyond my literary ability to describe the heartaches and headaches that accompanied the fun during almost two years of building.” Here was a grudging concession to market trends. Then, in April it “broadened the scope of its home-building program” to include material on house construction as well as design, “with special emphasis on those [activities] in which the owner can help.” It appointed William Scheik, head of the Small Homes Council at the University of Illinois, as technical adviser. They felt their way carefully “Within a three-mile radius of my house I have seen four amateur-built homes that are monuments to failure,” one writer declared in the April issue, while Scheik himself expressed caution. But by the fall, the magazine ran a more upbeat article that estimated cost savings from owner-construction of its featured Ninth Expandable Home. Over the next few years, it reported how resourceful readers handled the challenges of building their own homes.11

34. Consumer magazines learn to cater to owner-builders. It took months, and sometimes years, for magazine editors to recognize the magnitude of the amateur building boom. Source: Parents’ Magazine 24, no. 4 (April 1949): 51.

Others, supposedly better-attuned to housing trends, were equally taken by surprise. Disregarding market realities, in 1947 the Housing and Home Finance Agency had tried to help prospective home owners by distributing Planning Expansible Houses. Absurdly, it assumed that readers would hire an “experienced and competent architect.” Small Homes Guide was little better. Still edited by Wadsworth Wood, SHG was directed at those who wanted an affordable small home. Like most other observers, Wood assumed that this would mean mass production. Alternatively, recognizing that some prospective owners would want to build, he supposed they would hire a contractor. He also broached the possibility of hiring an architect, and mused that “your lumber dealer may act as contractor for the whole job.” By 1949, however, such experts were beginning to wake up. Kenneth Duncan changed his tune. In 1949, he wrote an upbeat commentary for bankers about the “surprisingly large number” of owner-builders, conceding that the subject might still occasion “some lifting of the eyebrows among those whose experience is mostly with cities and metropolitan areas.” At SHG, the letters column and a reader survey begun in 1948 forced Wood to change his tune. The survey showed that 55 percent of readers who had recently acquired a home had done at least some of their own work. (A later survey by Popular Mechanics reported that among that journal’s readers, 57 percent planned to do “most” of the work themselves.) In 1949, Wood launched a competition for stories of successful amateurs, and ran articles that offered tips. Late that year, a second survey revealed that 72 percent of buyers were now investing sweat equity, a finding reported by many local newspapers. Although government agencies still managed to ignore or downplay the owner-builder boom, consumer and trade magazines had finally woken up.12

If Corey’s prediction about homesteading was prescient, his comments about a looming housing shortage were common sense. For fifteen years, new construction had fallen behind the growth of housing need. During World War II, federal restrictions on materials had handcuffed the building industry. From 1940 and 1945 the GNP, and total personal incomes, had more than doubled, but the share going to residential construction had fallen from 3.2 percent to 0.6 percent. People had jobs, but nowhere to live.

When veterans came home, the problem ballooned (figure 35).13 Governments geared up to deal with the problem. In Toronto, for example, the city established a reconstruction council to assess the problem and recommend solutions. It showed that the housing backlog had been growing since 1931. Since then, about 8,050 dwelling units had been constructed and another 5,281 were created through conversions, but these were barely adequate for families. In every year from 1931 to 1945, marriages had exceeded new homes built, sometimes by a factor of six. The ultimate measure of hardship and, recalling what had happened after World War I, potential unrest was the situation of veterans. In March 1946, the council surveyed five thousand army veterans who had been discharged locally. A third were already married, and of these a large minority needed a home. One-fifth of the wives were living with parents, while some lived with other families or in rented rooms. The problem grew. In Peoria in early 1947, a quarter of unmarried veterans were living in rooms or doubled up, and a fifth of married veterans were in accommodation that lacked some basic plumbing facilities. Later that year, a national census found that this situation was typical. Fully 27 percent of married veterans were doubled up, more in New England and the Middle Atlantic states, fewer in the West. And, of course, many single men were aiming to find a wife and start a family as soon as they could.14

35. The postwar housing shortage. Source: Bill Mauldin, Back Home, 1947.

The Canadian and U.S. governments helped to revive the building industry, though building materials were scarce. Wartime restrictions had limited the use of materials for private homes. The result was a thriving black market. As Building Supply News reported in May 1946, many retailers and their customers believed that this favored large builders, who had influence and who could afford higher prices. That month, the U.S. government tried to revive production with a new Veterans Emergency Housing Program. Its director, housing expediter Wilson Wyatt, worked with the FHA to give priority to veterans, but progress was slow. The shortage favored amateurs, who could take time to scrounge used or unwanted materials. In most cases, they did so through informal networks of friends, family, and neighbors, but occasionally they adopted a more systematic approach. In Yakima, Washington, a veterans group made headlines by starting a “swap shop.” Media appeals got people to search basements, garages, and attics, and this enabled some local veterans to start building. Veterans had a special moral claim, but as a Peoria survey found in 1947, they were only a minority of those in need. Recognizing this, on Christmas Eve 1946, VEHP approval was extended to nonveterans, but only those building for their own use: operative (speculative) builders were excepted. The new administrative policy only lasted until May 1947, when the approval system was thrown open, but it had a significant effect. “Building for their own use” included those who hired contractors and also owner-builders. In fall 1946, a third of the veterans with official approvals took this route. After Christmas they were swamped by nonveterans. Between December 24, 1946, and May 30, 1947, almost twice as many nonveterans as veterans obtained permits to owner-build, and subdividers paid heed. In Peoria, The Knolls, a new subdivision, was marketed from March 1947 as an area where nobody now needed federal permission to build. Unwittingly, the federal government had given a short but sharp fillip to the amateur.15

If shortages of materials nurtured the amateur builder, those of tradesmen force-fed him. The building industry had been largely moribund for a decade and a half. Some tradesmen had retired or been killed in the war; others had retrained, and few young men had been recruited. The industry needed labor. In 1946, a regional expediter considered how the labor shortage might be filled, suggesting apprenticeship programs and a public relations campaign. Desperate, he entertained the idea of offering temporary permits (i.e., union cards) to veterans who have “learned sufficient skills in the armed services to be able to help build houses.” Some cities and unions cooperated. In Spokane, Washington, for example, the city allowed veterans to dig their own trenches for sewer and water connections, thereby saving municipal workers, and a mayor’s committee asked contractors to allow veterans to work on their own homes “along with regular construction crews.”16

Shortages translated into higher costs. Everyone associated with house building knew their services were in high demand. Some gouged, and a few sold at cost or volunteered their labor. In 1947, Edwin L. Jones, one of the nation’s largest builders (who helped develop Oak Ridge, Tennessee), donated his company’s services to build fifty homes for veterans in Charlotte, North Carolina. But most builders welcomed the opportunity to earn a better living, and so costs rose. In 1946, Howard Morris had urged his readers to build. Two years later he changed his tune. To a second, and largely unrevised, edition of his advice manual he added a footnote. “As this Guide goes to press,” he warned, “home building costs have . . . risen more than 85% above prewar costs.” As a result, “economists are . . . urging prospective home owners not to build or buy a house during this period of inflation.” It is a rare author who tells his reader, in effect, to set aside his book. More effectively than any statistic, Morris’s warning dramatizes the effect of cost inflation on house building after 1945.17

Morris ignored the sweat equity option, but others did not. In 1944, Paul Corey had claimed that savings could amount to 50–66 percent of total costs of construction. His estimate was generous. An analysis by the National Housing Agency found that site labor and contractor’s overheads accounted for 48 percent of the costs of the average small house, 45 percent counting site improvements, and 42 percent including the cost of land. It was a tall order for an amateur to do everything, but Corey was right to claim that the payoff was substantial. Five years later, when the amateur boom was peaking, those involved assumed that the desire to reduce costs was the main motive. When Time finally caught up with the trend in 1952, it agreed. Directly and indirectly, postwar shortages had given a boost to the amateur builder. Indeed, for many, they had left little alternative.18

The Promotion of Owner-Building

Once they had caught on to the amateur’s market, the media aided and abetted it. Parents Magazine and Small Homes Guide were two of a dozen or more magazines that gave assistance in the form of plans and advice. Plan companies, newspapers, and publishers did the same. Collectively, they reassured consumers that, after all, building a home was no big deal.

Plan services continued to offer basic help, though sometimes with a novel twist. A widening range of organizations, including the Southern Pine Association; magazines such as Small Homes Guide, Parents Magazine, and Successful Farming (originally a sister to Better Homes and Gardens); and specialized companies such as Standard Homes sold plans at very low prices. Standard had produced catalogs since the 1920s. After 1945, it produced a revised version of its Better Homes at Low Cost (1946), a booklet on Homes You Can Build Yourself (1949), and then a more substantial Standard Construction Details for Home Builders (1950), which contained isometric drawings together with estimating charts and tables. This was a consumer-friendly version of the technical manuals, such as Audel’s Carpenter and Builder’s Guide (1939), that professionals used. Construction Details included no text, but drawings showed consumers what to do, with estimating guidelines to help them bargain with local suppliers. The 1950 edition claimed that “more than a million live in homes constructed from our standardized plans,” which implied 200,000 houses. It is impossible to know what proportion of these were built by amateurs; perhaps half. In newspaper advertising, Standard claimed that “energetic men everywhere are now building this way.” Another, more novel approach was not strictly a plan at all. In 1936, Mr. Brann, a hobbyist in Pleasantville, New York, realized that one way to help amateurs make household items was to provide full-scale paper templates. His company, Easi-Bild Patterns, was soon doing a booming business, and during the building boom branched out into whole house templates. These were distributed in various ways, one being through “thousands of retail lumber dealers.” They became a phenomenon. As early as 1947, Brann drew the attention of the Washington Post, which reported his conviction that “anyone can build a house.” By 1950, several customers were featured in Readers Digest and the Ladies Home Journal. Two years later, Time reported that Easi-Bild had sold 250,000 house plans since 1945, of which Brann reckoned that 70,000 had been built. Nothing about house building is idiot-proof, but Brann had taken plan-making one step closer to that ideal.19

Magazines offered a different mixture of information, encouragement, and advice. At one end of a complex spectrum defined by class and gender, upmarket women’s magazines featured glossy photographs and plans. In 1950, for example, the Ladies Home Journal ran a series of three articles to show that “you can build your own home for half the price.” Its architectural editor emphasized he was promoting not the “minimum” but the “‘maximum house’ designed to be built for minimum money.” The third article reported that Jack and Virginia had erected a 1,400-square-foot home, now worth $18,000, for an outlay of $9,089.13”—plus 700 hours of work. Soon, Better Homes and Gardens also began to run features on amateurs, ranging from those who tackled funky garage remodelings in town and country to the case of Bill and Roma Maschal, who had not planned to build their own home but had been compelled to do so by the labor shortage. They took three years, during which time they “gave up on social activities.”20

Middlebrow magazines with a wider readership offered similar stories of more mundane projects. As early as 1945, American Home told about resourceful building by four “pioneers,” and soon House Beautiful, under the direction of Elizabeth Gordon, assembled a special issue about owner-building that included a report on Peoria, Illinois. In 1949, American Magazine recounted how a factory foreman had built a modest home; the next year, under the heading “Build a House in Your Spare Time? Why Not?,” Readers Digest explained how an immigrant factory worker with no construction skills had erected a two-bedroom house in New Jersey. Going one better, Americas recounted how all sorts of people had built for themselves, including an editor, a whisky salesman, a novelist, and, remarkably, blind Ernie Price from Terre Haute, Indiana, who managed with a little help from his friends.21

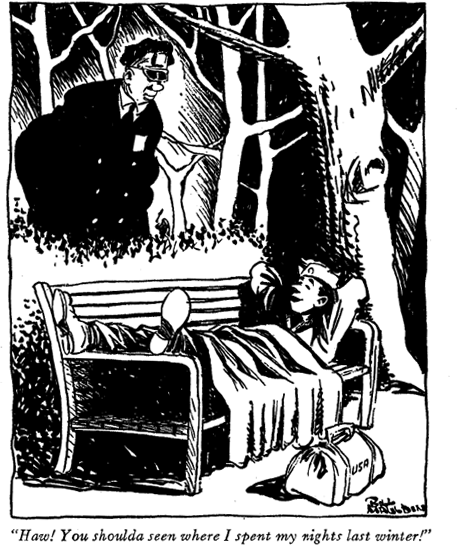

And then there were a few magazines, read mostly by men, that offered plans, stories, and reassurance, mixed with practical advice about financing and construction. In June 1953, for example, Popular Science Monthly explained how many amateurs had been helped by a Cleveland Savings and Loan. But what men most needed was information about how to build. Popular Mechanics was the go-to source (figure 36). Specific topics were addressed in articles, but building a home also called for strategic decisions, about sites, designs, materials, and framing methods (figure 37). This called for a book; eventually, Popular Mechanics published four. Three featured specific methods of construction: wood frame, concrete block and, as more dealers and manufacturers began to sell prefabricated kits, the precut house. A fourth focused on the most popular house style, the ranch.22

The idea for the first book came from James Ward, craftsman editor of the journal. The editors decided that, to demonstrate that “any man of ordinary mechanical aptitude” could build a house, they would have to find and teach such a novice, and report the results. They did not yet have the courage of their convictions. They picked Jacques Brownson, a twenty-three-year-old veteran and carpenter’s apprentice who had already bossed “a gang of coolies” on a wartime construction project. Brownson started work at a site thirty-eight miles west of Chicago on May 26, 1946, and completed the basic house by November 20. He received advice, together with some assistance from his wife (who did the painting), from an “inexperienced helper,” and from friends who helped dig the basement, but he finished the project mostly by himself in a single building season. The results, including an estimate that the whole job would have taken two men 2,000 hours, were written up and published in 1947. Readers responded enthusiastically, and the magazine soon produced similar accounts of a concrete-block and then a ranch house. By the time it described the assembly of a precut, it was persuaded that anyone could do the job. Richard Dempewolff, a staff writer with no special manual skills, built the house and wrote a first-person account. His precut needed 1,650 hours of work, including 500 carried out by professionals.23

36. An advice manual for owner-builders, 1947. Popular Mechanics published four such manuals in the late 1940s and early 1950s, leading the pack of publishers.

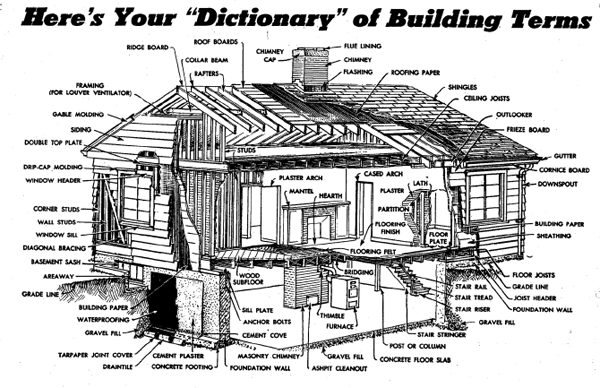

37. An illustrated building dictionary. Amateur builders needed to know how to talk to building suppliers and subcontracting tradesmen. Source: Popular Mechanics, Three Low-Cost Homes You Can Build Yourself (Chicago: Popular Mechanics, 1954).

Paul Corey and Popular Mechanics led the way in offering how-to manuals. While emergency restrictions were still in force, books were published on the use of adobe and rammed earth. Then, copying his coauthor Kenneth Duncan, Douglas Tuomey renounced his earlier reservations and offered his own tips on How to Build Your Own House (1949). In 1950, Publisher’s Weekly began a catalog of “How-To-Do-It” books, and the following year such manuals occupied three of the top five places on the nonfiction best-seller list, the fifth-ranked being the Handyman’s Book, published by Better Homes and Gardens. A widening range of improvement needs were being satisfied. As a variant on concrete blocks, Frazier Peters urged readers to Pour Yourself a House (1949); giving step-by-step guidance, and since there is no copyright on book titles, in How to Build Your Own House (1950) Hugh Laidman told readers what to do, weekend-by-weekend; for the ambitious, Lee Frankl led readers step-by-step in erecting The Masonry House (1950); for students, Deane Carter and Keith Hinchcliff offered a dispassionate guide to Family Housing (1949); and, for those who needed motivating, Paul Corey produced Homemade Houses, which mixed tips with dozens of inspirational examples. Most successful of all was Hubbard Cobb. By 1949, Cobb had become editor of American Home, was the “famous radio handyman” on a syndicated show that broadcast on Saturdays at 2:15 p.m. (a good time to catch a male audience), and wrote an advice column that appeared in Canadian as well as U.S. newspapers. In 1948, he had published a general work for handymen that had sold 500,000 copies and in 1950 he produced a specialized guide, Your Dream Home: How to Build it For Less than $3500, based on two years’ research. He then edited an Amateur Builder’s Handbook, with “over 1001 picturized new ideas” that “show how to save hundreds of dollars in home building and repair.” These books were crammed with practical tips, and dispensed with exhortations. The opening sentence of Cobb’s Handbook read in full: “The silt test is used to detect the presence of too much extremely fine material.” He was preaching to the converted.24

Newspapers performed a different function, operating as a clearing house for insights, tips, and motivational reports, as well as key local information. The Peoria Journal-Transcript, Peoria’s leading daily, was typical. In the late 1940s, it published general news about the owner-building boom: tales of pioneers working collectively or individually in Ypsilanti, Atlanta, Oklahoma, or rural Alabama, the latter being a scheme for African-Americans run by the Tuskegee Institute. The PJT included advertising for the Standard Homes catalog; notices for how-to manuals such as Douglas Tuomey’s; notices about how to get free building information from Scheik’s Small Homes Council. It summarized the talk that Scheik gave at a local Home Planners Institute meeting sponsored by local dealers and lenders, and published a myriad other reports and tips. In 1945, it began a column about building and repairs, and noted changes in the priority system for veterans. In 1946, it alerted readers to a new Apprentice Training School for veterans, along with an open house. In 1948, it noted that Central Illinois Light Co. was running demonstrations on home wiring and then, in 1949, that a free library for home planners was opening to coincide with the second annual postwar home show. The latter included “live” studies of home construction, including carpentry, roofing, brick laying, plastering, and sheet metal work. And of course it included advertising from realtors, subdividers, lumber dealers, and lenders, all of which was essential to the amateur builder. Among advertisers, Wahlfeld Lumber and First Federal Savings and Loan were again at the forefront, but others reinforced the message. The subdivider of Beverly Farms tried to pique interest with the blunt question “Are You a Handy Man?,” while in September 1945 Brown Brothers reminded readers that wartime priorities would soon be relaxed. Citizens Real Estate Co. pointed out that in their subdivision at Ravinwood Farm, buyers could hire contractors or build their own. In nearby towns, such as Pekin, other lumber dealers, notably Reinhardt, also developed service packages for amateurs (figure 38). And on and on; the examples could be multiplied scores, indeed hundreds, of times over.25

38. A dealer-assisted owner-built home, Pekin, Illinois. In Pekin, for some years after 1945, Reinhard lumber provided a complete package of materials and services to amateur builders. Photo: author.

Unusually, the Journal-Transcript could report national coverage of local events. In 1948, the Institute of Life Insurance chose a Peoria family for “making the most of their opportunities and . . . getting ahead.” This was reported in 375 papers nationwide. The Journal-Transcript noted that the Hintons, who had both come from “broken homes,” had earned this honor in part because they had “built their own home with their own hands.” Local readers might have wondered how this made the Hintons exceptional. In most other cities, newspapers could not have stirred amateurs’ pride in the same way, but they routinely blended general reports with local news and advertising in a manner than encouraged owner-building. In Toronto, for example, a leading daily began a Homecraft page in 1950, and two years later estimated that 20,000 Toronto families had built their own homes since 1945. This was educated guesswork, and probably understated the trend. But here, as everywhere, newspapers were key facilitators and boosters of the amateur boom.26

After 1950, the pace of publication fell off. The change was most obvious among the manuals. In $500 . . . and a Home of Your Own (1952), Elsa Andrezen gave a personal account of how she and her husband had built in the vicinity of Washington, D.C., illustrating the process of building in stages (figure 39). She played up the story more than the technical details. George Daniels offered guidance on How to Build or Remodel (1953), Katherine Ford and Thomas Creighton considered Quality Budget Homes (1954), and then Larry Eisinger surveyed How to Build and Contract Your Own Home (1957). In each case, discussion of owner-building was mixed with related commentary, whether on remodeling, cooperatives, or the hiring of contractors. Indeed, by 1954 Ford and Creighton felt free to pooh-pooh the idea. Yes, they said, you may build yourself, “if you are an extremely clever person with infinite time on your hands, if your local building codes permit . . . , if you are willing to put up with some crudenesses . . . , and if you are willing to run the risk that in the long run (due to expensive mistakes) the house may cost you more.” There had always been mixed opinion about the whole idea but, after 1950, the balance had shifted back.27

The tide of amateur building had turned. The high point probably came in spring 1950, since U.S. entry into the Korean war in June meant that many men who had planned to build were called up. Small Homes Guide published a letter from a Mrs. A. J. Stefanick, who explained that when her husband had to go overseas they changed their plans and hired a contractor. The effect of the war was immediate. A running survey of six major metropolitan areas showed that rates of owner-building inched up from 13 percent of new single-family dwellings in the second half of 1949 to 14 percent in May–September 1950, but then dropped to 10 percent by the first quarter of 1951. Nationally, four years later, the incidence of owner-building (14 percent) was less than half its level in 1949. It then fluctuated around that figure for the next two decades.28

39. Building in stages. Large lots made it easy for single-story dwellings to be expanded as family size required, and finances allowed. Sources: Elsa L. Andrezen, $500 . . . and a Home of Your Own (New York: Vantage, 1952).

Attitudes

If circumstances changed, there was also a new can-do attitude. During the Depression many men had tackled house repairs, or more substantial conversions. Then, as Corey said, war compelled them to do “so damned many things which ‘couldn’t be done,’ or which ‘you couldn’t do’ . . . that the building of a house would be a pushover by comparison.” Young women too had been challenged, and Corey evenhandedly addressed them as well: “You dames can build ships and bombers, tanks and cannon, then why in hell can’t you build your own homes from foundation to roof?” Frazier Peters echoed this spirit when he separated Americans into “those who holler for houses and those who go out and get them.” And indeed the war mattered. It was a veteran that Popular Mechanics asked to tackle the magazine’s first building project. More soberly, reporting his institution’s experience in making loans, Thomas Craig observed that “service in the armed forces taught a lot of GI’s to be resourceful.” Inconceivable became possible.29

Some writers claimed that amateur actually welcomed the challenge of building. Perhaps they were right. It is a cliché that after fifteen years of depression and war, young men and women embraced secure domesticity. By the 1950s that may have been true, but it skates over the awkward period of transition, when men adjusted to mundane routines while women had to redirect their energies into their homes. Is it mere coincidence that this transition period saw one of the greatest ever booms in owner-building? Corey reckoned not. He suggested that, after spending time in North Africa, Europe, or the Pacific, veterans would find home life dull, so that “building your own house would be just the sort of occupation to taper off to normal life on.” Just so. More obviously, as many argued, building a home offered challenge and fulfillment: Cobb spoke of “satisfaction,” while Daniels refers to “very real pleasure” to be shared by “every member of the family,” who could enjoy their ability to make a home as they wished.30

The point should not be overstated. These writers had a stake in encouraging people to build. Read carefully, their manuals show that authors knew that a fear of debt weighed at least as heavily as the possible pleasures of building. Reinforced by the Depression, thrift was still valued. Again, Corey put it pithily. Discounting the long-term mortgages promoted by the FHA, he pointedly asked: “Look back into the past. How long have you had a steady uninterrupted income?” Indeed, “How many people do you know who have had an uninterrupted income for as long as twenty-five years?” The alternative was obvious. As George Daniels recognized, the advantage of starting small and building in stages was that you could “pay as you go,” thereby minimizing debt. The owner-builder took this to a logical conclusion. In the end, Corey exclaims, “it’s free and clear of debt. There lies security that can’t be beat.” As lenders soon realized, many families thought this way. By 1949, Kenneth Duncan had learned that, “as a rule,” the average homesteader “dislikes debts and correctly . . . looks upon a mortgage as a debt.” One such was Mrs. Clara Sanders from Elk, Washington. In a letter to Small Homes Guide in 1948, she explained that she and her husband were planning to take ten years to build because they were “determined to pay as we go.” The consequence, of course, was that where amateur building was common, blocks took on a provisional and higgledy-piggledy appearance (figure 40).31

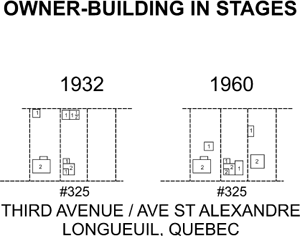

40. The imprint of the owner-builder. Areas where owner-builders were active evolved steadily, and in eccentric ways. Redrawn from Canadian Underwriters’ Association, Insurance Plan of the City of Longueuil, Quebec (Montreal: Canadian Underwriters’ Association, 1932 and 1953, with revisions).

Of course it is still possible to speak with those who built homes at that time. In the summers of 1995 and 1996, a student and I interviewed thirty-four people who had built their homes in Peoria, Illinois, four before the war, and the remainder after. Six had erected two or three dwellings, in sequence. Looking back, all expressed pride, most claimed to have enjoyed at least part of the process, and several insisted on showing us innovative features or excellent work. For example, Mrs. Andrews claims that she and her husband found the building of their home in Peoria Heights in 1947 to be “pure enjoyment and satisfaction.” But when asked why they had chosen to build, almost all referred to their desire to avoid debt, or their lack of choice (figure 41). Even Mrs. Andrews, for example, spoke of “our saving habit” which encouraged them to “pay as we went.” Ed Schlaffer, who started construction in 1951, underlined a more basic fact. Schlaffer was one of several interviewees who took a strong interest in our project. He took it upon himself to make inquiries among friends and neighbors, and reported their consensus that families had built homes because of the housing shortage, and to save money or minimize debt. Enjoyment and pride were pure gravy.32

Thrift and financial caution were even more dominant in Canada. At that time (and to this day), Canadians did not rely as extensively on mortgage debt. Finance was especially scarce in the early postwar years because, until 1954, banks were prohibited from making mortgage loans. To explore their motives, and helped by another student, I interviewed forty-five owner-builders in Hamilton, Ontario. Hamilton is an industrial city, slightly larger than Peoria, located eighty kilometers west of Toronto. Those interviewed expressed great pride in their accomplishment. A large minority emphasized that their main motive was thrift, which not only shaped their method of acquiring a home but their very desire to own. Greg Fishhook, for example, a veteran who bought plans from an American magazine and started building in 1951, insisted that he had never borrowed anything: “That was the way I was brought up.” The Depression taught him that the “only security you have is in your hip pocket.” The Ambridges would have liked to buy—as a drill-press operator at Westinghouse, Bill had no construction skills—but they, too, recoiled from the idea of “buying on time.” As Bill nodded in assent, Vera commented that “we could have sold our souls and bought one of the houses they were peddling” but “I never have liked to owe money.” The Hiscoxes, who built in the neighboring suburb of Burlington in 1952, were just the same. Arthur, too, was a veteran, who returned from Europe with Enid, a war bride. She brought the conviction that “to be in debt was shameful.” Her neighbors had the same opinion. Following the Depression, she was “petrified” of taking on debt and recalls that this was “a common attitude at the time.”33

Strikingly, none of those interviewed in Hamilton or Peoria, or whose stories were reported in the media of the time, spoke of investment. They wanted something useful, and never considered their efforts were financially shrewd. This was typical of home buyers in general. Architectural Forum’s survey found that over a third of potential buyers saw ownership as “more economical” than renting—that is, in the long run it cost less—but none saw it as an investment, even those who were well-off. Another survey, of professionals who bought in Detroit, found that only a minority had considered it an investment; their concern was with savings. In 1946, when Howard Morris enumerated why families should buy, he emphasized the same thing. Some even argued that owners were bound to lose out. In 1945, part of John Dean’s reasoning against home ownership was that “the American family must get used to the idea that the house it buys will not retain its value over a span of time.” Like Corey, who assumed that income was unpredictable, Dean made inferences from recent history. As late as 1953, even George Daniels—obviously a believer in home ownership since he wrote about how to achieve it—echoed Dean. There are many reasons to own, Daniels suggested, but money is not one: “Your house will tend to decline in value as time goes on.” Moreover, since most home owners did not yet pay income tax, the advantage of mortgage debt that Americans now take for granted was not yet relevant. To be sure, by 1945, most Americans and Canadians were committed to the idea acquiring a home. They shared few of the reservations that had persisted into the 1920s. When, speaking to a room full of veterans, Nathan Straus enumerated the disadvantages of buying, his audience could barely muster polite applause. Buyers in general, and amateurs in particular, were driven by immediate needs.34

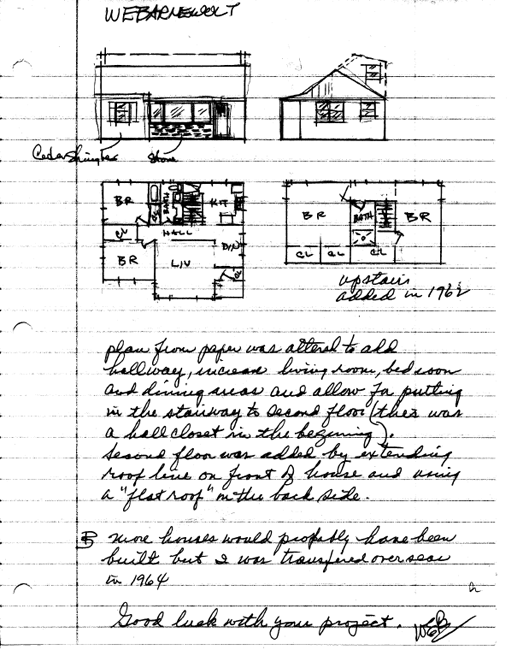

41. Amateurs often adapted published house plans. In Peoria, the Barnevolts built in the 1950s and extended their home in 1962. Source: W. E. Barnevolt, communication with the author. Used by permission.

The Amateurs

Their motives give a clue as to who the amateur builders were. They included anyone who was frustrated by the postwar housing shortage. The worst affected were the young, and those who had postponed home buying (or marriage and children) because of the Depression and the war. In other words, they were men and women with diverse backgrounds and skills.

Once they caught on, the media delighted in claiming that “anyone can build a house.” So did those who catered to the amateur. Corey flaunted the fact that before tackling his first building project he had “never mixed cement or waved a mason’s trowel,” while Popular Mechanics claimed that “anyone who could saw a board, drive a nail and follow simple instructions was quite equal to the task.” They were right. To be sure, construction workers did make up a disproportionate number of homesteaders, 33 percent according to an authoritative study of the Bay Area. A number of the men featured in media accounts, such as those published by Time or House Beautiful, were associated with the building trades—architects were a favorite. Such men had relevant skills, and friends who could help out. Indeed, manual workers of all kinds were probably overrepresented among amateurs. Kenneth Duncan believed so, and, again, published accounts such as those in Readers Digest and Insured Mortgage Portfolio, bore this out. But a large minority had no relevant skills. Better Homes and Gardens featured a family where the husband was “aircraft company executive.” Another article, in Insured Mortgage Portfolio, told of a group of amateurs in Ypsilanti that consisted largely of men in white-collar occupations, including businessmen, professionals, junior executives, and instructors at a local college. And in all of the reported examples, women had no relevant expertise.35

The Peoria interviews fit this pattern. From those interviews that yielded relevant information, ten of twenty-two men had some useful experience. Five, including two electricians, a bricklayer, a carpenter, and a self-taught architect, were in the construction industry. The other five had accumulated skills in different ways. Mr. King and Dan McLeod, for example, both from rural backgrounds, were handymen who had picked up stuff “through necessity” or “trial and error”; Ed Schlaffer was an engineer, and had worked one summer as a laborer on building sites; Mel Schmidt, too, was an engineer, with a friend who took him up in his airplane to get a birds-eye view of the building site (figure 42). The remaining twelve men had no background in building. A number did manual work in local factories, including three machinists, and several had white-collar occupations, including a teacher, an engineer at Caterpillar, and a bookkeeper. Amateurs were not a social cross-section of the population, but they were people with a wide range of occupational skills.36

Some writers claimed that amateurs built better than professionals. In Canada, a lobbyist urged government to harness the homesteader’s energy. “To the consternation of professional builders and unions,” he insisted, “it has . . . been found that quite inexperienced home builders, clerks, bankers, postmen, bakers, with the help of a simple pamphlet of instructions will do a more careful and better job” than the professional, “even if slowly.” Several Hamiltonians took this to heart. Everett Englard, for example, who worked in a tool shop, built three homes for his family between 1952 and the late 1960s. This took almost two decades, but he expressed no regrets. “There was an awful lot of shoddy workmanship,” he explained. The same sentiment was apparent in the United States, as was indicated by evidence gathered by the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs. Under the terms of the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act of 1944 (and a later Veterans’ Rehabilitation Assistance Act of 1952), veterans were offered easy financing. To weigh the impact of this program, in 1956 the committee analyzed the 4,549,098 loans made to date. Their report noted much evidence of poor construction. The authors did not compare amateurs with professionals, but several comments are suggestive. They attributed some failures to ignorance, but many more to corruption, or the builder’s desire to save money by cutting corners. All examples of poor construction referred to speculative builders. Of course, some cases had come to the committee’s attention because of complaints, and amateurs did not complain about themselves. But inspectors and lenders might have blown the whistle on amateurs, yet the report does not mention a single case.37

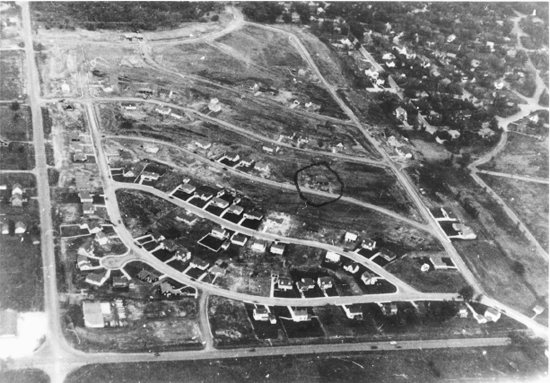

42. Views of the Schmidt home, Peoria, 1947. During construction, Mel Schmidt took the opportunity to photograph his home (circled) from a friend’s small plane. The couple sometimes brought their first child to the building site so that both could work on their home. Source: Schmidt family records. Used by permission.

As the housing shortage receded, it is likely that the quality of professional work improved. William Shenkel studied shell houses that were built 1961–1962. He found that the finishing work done by contractors was superior to that of amateurs, especially on interior walls, painting, and flooring. Some owner-built homes were worth less after eighteen months than as mere shells. Shenkel suggests this was largely true in areas where buyers had to rely on installment loans rather than mortgages, and where they were unable to afford quality tools and materials. It seems, then, that those who felt compelled to invest sweat equity did poorer work than those who had some choice. As the quality of professional work improved, it surpassed the efforts of the marginal home owner.38

If amateurs built better than professionals, it was because they cared more and took their time. Corey used several stories in Homemade Houses to make the point. Of one house, built by an unskilled veteran of the merchant marine, he claimed that “there isn’t one out of a thousand contractor-built jobs built today that can equal it.” Another amateur, who had contracted some work, reckoned he could have done better himself. When conceding mistakes, Corey treated them as minor. Darrell Huff was a friend from New York who had moved with the Coreys to the Bay Area in 1946. With no formal training in the field, Huff soon made his name as the author of How to Lie With Statistics (1954), a best-selling textbook. With help from Corey, Huff also taught himself how to build (figures 43 and 44). Corey claimed that, despite “slight waves and irregularities,” Huff’s concrete block wall was basically solid. An especially rich story is contained in the lightly fictionalized autobiography of Antanas Sileika. The son of European immigrants, Sileika grew up in a Toronto suburb in the 1950s. He describes his father building a home, one of several on the street that were going up in stages. Only one family had bought a finished home, a British couple who looked down on everyone else, and especially the Sileikas for living in a basement home. This was ironic since, a generation earlier, a huge wave of British immigrants had transformed Toronto’s suburbs through owner-building. Within a couple of years, of course, Sileika suggests that it was the British couple whose basement developed a crack.39

Again, the Peoria interviews bear out this sort of comparison, the Andrewses being a case in point. Mr. Andrews learned construction from how-to books. He and his wife had moved into the basement as soon as he had laid the concrete block walls, put rafters in place for the subfloor, and covered them with tar paper. Looking back, Mrs. Andrews claimed to know “every screw, nail, and bolt in this house” and declared that the structure was so sound that “if anyone ever wanted to tear it down they would have to dynamite it.” Is the statement true and, if true, is it typical? Who knows. Inevitably, amateurs look back on their labor with pride. Those who agreed to be interviewed must have included a disproportionate number of success stories. The only certain conclusion is that almost anyone could have done a good a job if they had the time and proper materials.40

43. Paul Corey in action, 1951. Paul Corey wrote two manuals for amateurs and inspired thousands, including his friend, the writer Darrell Huff. Source: Darrell Huff, “They Build Their Own,” Americas 3, no. 2 (February 1951).

In fact, few amateurs did everything. Today, major improvement projects usually combine the efforts of contractors and amateurs. The same was true in the early postwar years. In 1946, housing expert Miles Colean told readers of Small Homes Guide that owner-builders usually did from one-third to one-half of all their construction labor. Later surveys confirm this. In 1948, 12 percent of SHG’s readers who had recently acquired a home said they had done all the work, while 55 percent had done some. The best survey was undertaken in the 1960s by the Census Bureau. It found that a fifth of amateurs did everything, while a quarter simply acted as general contractor. About half completed 35–75 percent of the work. In 1951, SHG reported the variations by type. A small majority did their own framing (52 percent) and roofing (56 percent), while more did interior walls (59 percent), finishing (61 percent), and flooring (65 percent). A minority installed heating systems (40 percent), plumbing (32 percent), or wiring and glazing (31 percent). These statistics make sense: amateurs did the least skilled jobs, those where errors mattered least and where building regulations permitted. They are also consistent with the reports of those I interviewed in Peoria, Illinois, and those published at the time. For example, the factory worker whose story was told in Readers Digest did everything except plumbing, heating, and wiring. The Kenetters, in a letter to SHG, say they hired an electrician only because the municipality required them to do so. The factory foreman whose story was told in American Magazine employed an electrician and plumber for the same reason. Amateurs took charge, and did what they could, but most also relied to some extent on the building trades.41

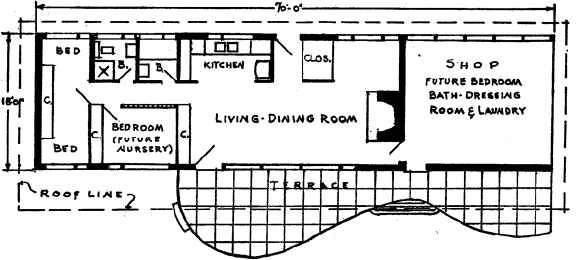

44. The Huff home, c. 1948. Corey used this ground plan of the original Huff home to illustrate how amateurs could build in stages. A future bedroom at first served as the workshop. Source: Paul Corey, Homemade Houses (New York: William Sloane, 1950), 122.

Amateurs also used friends, family, coworkers, neighbors, and indeed anyone they could rope in. A study in rural North Carolina found that almost everyone received help: one-third from relatives, one-fifth from neighbors, and some from tenants. Among relatives, sons (22 percent), brothers (16 percent), and brothers-in-law (13 percent) did something. Many of Paul Corey’s “case histories” from suburbia and exurbia confirm this picture. In Cleveland, for example, Howard and Donna Whittakers were helped by Howard’s brother and father on weekends, Donna’s brother “practically every day for three months,” Donna’s cousin, and also her uncle, who came from Detroit on weekends. Media accounts, however, played down the role of family and friends in urban or suburban settings. This is true of the case studies and letters published in Small Homes Guide and Parents Magazine. The Simoniches, of Belmont, California, seemed unusual for exchanging labor with an acquaintance whom they later helped in turn, and so did the Sileikas in Toronto, Ontario, for relying on friends and on cousin Stan, who was paid in liquor. But my interviews in Peoria and Hamilton confirm that formally and informally traded labor was the norm.42

In Peoria, of the thirty-four households interviewed, sixteen recalled receiving help from extended family and fourteen mentioned friends, neighbors, or coworkers. Extended families often included tradesmen. Virginia Oedewalt recalls that her husband’s cousin, who owned a team of draft horses, helped dig the basement, while another cousin did the wiring. The Harrises received help from Jack’s father, a carpenter, and his brother, an electrician. When family members lacked specific skills, as in the case of the Andrewses and the Barnewolts, they still helped out by digging, carrying, sawing, hammering, or mixing cement. Similarly with friends. Boyd Harris received help in several ways: a friend returned a favor by doing some cement work; neighbors, “curious at first,” gave “volunteer help,” though “as I got going they were not so interested”; he also traded labor with coworkers, who held “roofing parties.” The same happened in Hamilton, Ontario. Mel Colling, for example, got the idea of building by first helping his brother. Glenn Gibson was helped by his father, brother-in-law, and a cousin “who came [to Hamilton] on a weekend and helped me install the subfloor and [later] the roof” (figure 45). Jack Graham went one better. His father pitched in, and he also cooperated with five coworkers at Otis Elevator: “They all worked on one house and then they’d work on the next, and the next.” Cooperation was almost inevitable on blocks such as the Gibsons’, where several were building at the same time, Friendships were both used, and forged. In remoter, exurban settings, such as those chosen by Paul Corey, homesteading was individualistic. In suburban and nearer fringe areas, it built communities as well as houses.43

Cooperation was usually informal. Nobody kept a tally of hours. But sometimes exact agreements covered labor, financing, and materials. Before the war, a few building coops had organized and attracted media attention. Most erected single-family dwellings that, when finished, became privately owned homes; some were inspired by Depression-era homesteaders. The postwar shortage gave them new impetus. In Canada, a prewar cooperative plan, eventually sponsored by the Province of Nova Scotia, was mothballed during the war but revived after 1945 (figure 46). Building coops became active in other provinces, notably Quebec, though only a minority used amateur labor. Building coops took a different course in the United States, where they briefly caught the public eye. In 1947, Newsweek reported that a Detroit vocational training instructor had assembled forty-seven veterans who bought lots just north of the city line and spent ten hours each weekend working on each others’ homes. Reports on the coops appeared in many publications, including Small Homes Guide, House and Garden, Parents Magazine, Christian Science Monitor, Commentary, The Survey, and the New York Times, as well as trade press such as Savings Bank Journal. Accounts of Canadian schemes appeared in comparable media, including Maclean’s, the major news weekly, papers such as the Toronto Star, and even U.S. publications such as Newsweek and Commonweal.44

45. Block party of amateur builders, Hamilton, 1957. On many suburban blocks, cooperation among owner-builders built community too. Source: Glenn Gibson, personal records. Used by permission.

Financing was the challenge, and “in response to a Nation-wide demand by veterans groups for information and advice on cooperative and mutual housing enterprises,” the National Housing Agency and the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed how groups might proceed. The UAW-CIO, and other interest groups, pushed the idea. By 1949, a financing manual was published and, after much lobbying, revisions to the National Housing Act made provision for coop financing. Coinciding with the peak of amateur building, this stimulated a mini-boom in cooperative building as well as ownership. But federal support wavered, and even at its peak the quantitative contribution of coops never amounted to much. In 1951, an authoritative survey projected a total of 28,000 units and, after 1952, interest in coops waned even more rapidly than individual owner-building. Informal assistance was common, but formal cooperation was a minority taste. Among those interviewed in Peoria only one family, the Kathuses, had been involved in a building coop, which, typically, had conformed to no stereotype. It was formed by a Catholic priest who was concerned about the shortage of housing for large families. Sixteen families chipped in to buy land along an extended cul-de-sac. Contractors built shells, and families laid floors, finished sidewalks, painted, and landscaped. When the Kathuses moved in, there were already sixteen houses and ninety-six children. Two families eventually had fourteen each; Olga Kathus drew the line at six.45

46. Consultations for a co-operative owner-build project, Nova Scotia, 1939. Organizational advice was offered by Mary Arnold, from the Co-operative League of the United States, headquartered in New York City. Source: Mary Arnold, The Story of Tompkinsville (New York, 1940).

Mrs. Builder

For all the outside help that families received, their success depended on how well husbands and wives worked together. It was usually the woman who ran the household: who purchased and cooked the food; who shopped for other necessities; who tidied and cleaned; and who looked after any children. Most couples were young and wanted a home before having children, and so it was common for women to take on tasks usually reserved for men. These included the buying of materials, a challenge for the retailer. But many already had children and still pitched in.

Occasionally, the media featured a woman who transgressed all stereotypes. American Home reported that, between them, a mother and daughter in Berkeley, California, had erected a small house. The Hamilton Spectator described how a Dutch immigrant had gone one better, building a substantial two-story house by herself. Many women who had done something like this were pleased to tell their story. For example, when Americas published a report on owner-builders, a staff photographer, Frances Adelhardt, alerted her own employer to the fact that she had built a two-room cottage just eighteen months earlier—helped by her father and half a dozen “good Samaritan” staff members. One of Corey’s case histories described a woman with two children who had built a home, in New Milford, Connecticut; he also claimed that Miss Anna Kaiser, sister of the west-coast industrialist, had built no less than three dwellings, in part, with her own hands. Such women were treated as examplars of resourcefulness, but they were obviously exceptional.46

The norm was that men took charge of building. After Don Wharton interviewed seven people for an article in Readers Digest, he wrote only of men. More typically, women were viewed—by themselves, by their husbands, and by reporters—as helpers. Miles Colean, for example, noted in passing that women might have some relevant skills. The most obvious pertained to the beginning and the end of the process: design and decoration. Symptomatically, accounts of the Popular Mechanics house projects refer to wives mostly as painters. Darrell Huff reported that his wife took the same role. Some reports show women being more actively involved. Photographs taken of the Coreys indicate that Paul’s wife helped out on the building site (figure 47). Not surprisingly, Elsa Andrezen’s book told how she did various tasks, including the laying of concrete blocks. More surprisingly, the Ladies Home Journal reported that Virginia Phillips “helped” dig and waterproof the foundation, and then plumb, wire, and paint, both inside and out. Corey tells how the Paveys built with adobe: while Bob earned, Phyllis dried the homemade blocks by turning them, laid the outside and partition walls, together with the fireplace, and then nailed the tongue-and-groove floor while carrying their first child. More commonly, women shopped. It was Phyllis who hunted down nails and sheetrock. Another LHJ story told that “Jack” invested 550 hours of “hard work,” while “Virginia” (not Virginia Phillips) spent 150 hours “running errands and keeping accounts” as well as “shopping for materials and equipment.” In Small Homes Guide, Maxine Livingstone noted that in the Simonich household “Mother acted as purchasing agent,” as well as “third-class helper.” Darrell Huff sent his wife out to buy materials, as did Paul Corey. Shopping for materials extended a role that women already knew, though it required new skills and knowledge. Livingstone reports that in the Mongold family, George worked on the house during his spare house while Nell occupied her free moments “in town searching for items we had listed the night before.” Nell added, “I found myself acquiring a contractor’s vocabulary.” Purchasing agents like Nell Mongold had to learn how to shop for new goods but, equally, lumber dealers had to figure out how to cope with a new type of customer.47

47. The Coreys working on their home. The photograph appears to be candid, although only Paul is dressed practically. Source: Papers of Paul Corey, MsC 585 (Iowa author), Special Collections, University of Iowa Libraries.

That women played an active as well as a supportive role in the building process is confirmed and amplified by those interviewed in Peoria and Hamilton. Support and thrift were taken for granted, as when Millie Wegner carried hot casseroles by bus from the couple’s apartment to the building site, where she met her husband after his day shift. Almost all wives helped select, or draft, a design, none more so than Rosemae Johnson, who had trained in home economics and worked in the Tasting-Test Kitchen of Better Homes and Gardens magazine before she and her husband, Lloyd, moved to Peoria from Des Moines. Lloyd, a self-taught architect, admits that “Rosemae taught me the fine points of room arrangement.” Vera Streits helped her husband design the house they built in Hamilton in 1950: Vilis was a civil engineer, but as a DP from Latvia he had little English, so Vera translated the technical vocabulary in the books she borrowed from the library. “You were my ears and my eyes,” Vilis recalled. About a third of the wives interviewed did substantial construction work, even those with children. In Peoria, recalling how her parents built their house, Marge King recalled that “mother would troop all the [six] kids to the site and work every day,” adding that “she was always working . . . no rest.” Dan Letizia remembers that his wife, “pregnant at the time, helped with nailing 1 × 8 roof sheathing,” while their “nine year old son helped by carrying materials and watching little brother and sister.” In Hamilton, Vera Butterworth recalled “hammering nails in the subfloor while a-hanging on to a kid,” to which her husband added, “and carting cement blocks when you were pregnant.” (“Yes,” Vera agreed, “we were desperate.”) Alec Barrett’s wife helped with “pretty near everything except the shingles—she didn’t like the height.” In each city, two couples switched breadwinner roles. In Peoria, Martha Grouper went out to work while her husband and father took leaves of absence to get a house finished quickly; in Hamilton, Mrs. Millard “went to work part-time to help because we were running out of money.” And at least a quarter of the wives took the major role in buying materials. Floreine Harris’s experience was typical. She drew the plans for their second house, in 1953. Her husband’s brother owned a truck and, as construction proceeded, Floreine used it “to haul supplies from Sheridan Lumber Company in Peoria. Their prices were the most reasonable.” To which she added, “I would take my daughter with me, of course.” All of this confirms Strong-Boag’s claim that on building sites women were “as active in all weathers as their husbands.”48

The details depended on personal circumstances, skills, and values, but the constant theme was teamwork. Universally, women were responsible for housekeeping. Beyond that, few gave much thought to social norms. When Mrs. Millard was asked whether she felt pleasure, pride, or stigma in working on the family home, she simply replied, “I haven’t actually thought about that. It had to be done. He was trying to do everything on his own and he needed help.” This response was typical.49

What men and women did worry about was finance, technical details, and managing the building project, which entailed awkward problems of scheduling, not to mention the letting and supervision of subcontracts. Magazines and manuals could offer encouragement and general guidance, but every project posed unique problems. Amateurs needed specific help, above all from local lenders and suppliers. Paul Corey knew this. In 1944, he advised his readers to talk to “the local lumber dealer, a font of wisdom.” Later, he used Howard Whittaker’s experience as a caution: having dealt with twenty-five different businesses, Whittaker recommended that amateurs “find one place to buy your materials” since “a friendly dealer can show you many ways to save.” Corey also urged amateurs to pay cash to create a good impression, indicating that many retailers were still not reconciled to the consumer trade. Even for those suppliers who evolved during the 1930s, the owner-building boom tested their ability to satisfy the consumer, and on a greatly enlarged scale.50