ELEVEN

The Improvement Business Coalesces

People had always maintained their homes, but home improvement became a recognized industry only in the early 1950s. It got the attention of retailers, advertisers, consumer magazines, and, through the media, a wider public. Although contractors and tradesmen had a large piece of the business, a substantial and growing amount of the work was now done by home owners themselves. In so doing, they saved money and embodied their commitment to family life. Do-it-yourself, a term popularized between 1952 and 1954, became chic, and then a social expectation. Manufacturers and retailers responded aggressively to this cultural shift, and in so doing fostered it. By 1960, home improvement had become a self-propelling phenomenon.

Improvement through Peace and War and Peace

It is no coincidence that the first serious attempt to measure home improvement came in 1954. Until then, estimates had cobbled together building permit data with the impressions of building suppliers and contractors. But permit data were incomplete, minor repairs and alterations were hard to count, and plenty of work left no paper trail. It was obvious that investments in this area counted for a lot: the U.S. Department of Commerce had calculated it was worth $6.5 billion annually, about half the investment in new construction, but because the accuracy of this figure was doubtful the census bureau tackled the issue in detail. Surveying two thousand home owners in eighty-six places, and following up with field checks, they estimated $8 billion was spent on owner-occupied homes, $4 billion on rental properties, for a total of $12 billion. This meant that work done on the existing housing stock was as important as new construction. This conclusion was consistent with the results of surveys carried out by the NRLDA and the American Lumberman in 1950, which found that in urban areas home improvement accounted for 46–47 percent of the retailer’s trade. Home improvement was big business.1

The term embraced a subtly different mix of possibilities. The census bureau made broad distinctions: “alterations and improvements” made up the largest share (47 percent), followed by “repairs and replacements” (42 percent), with “additions” (11 percent) trailing. The terms speak for themselves and in principle were distinct, though reality blurred lines. A recent survey in Britain indicates that household members do not make such sharp distinctions. When they “repair” or “maintain” they also often “improve.” It helped contractors, retailers, and manufacturers to have a rough idea of the types of construction being done, since they required a different mix of tools, materials, and services, but they knew these were a continuum.2

More important was the trend. The census study underlined how inadequate the existing data were. These suggested that, in 1954, expenditures on additions and alterations accounted for 16.5 percent of total residential construction; including repairs, this suggests a total figure for improvement of barely 25 percent, about half what the census study shows. But the imperfect annual data do indicate the trend. (Figures in parentheses have been adjusted to include repairs, and then doubled.) The share of improvements fell in the second half of the 1940s, reaching a postwar low of 13.4 (c. 38) percent in 1950. It then rose in waves, first peaking at 17.9 (c. 50) percent in 1954, 20.4 (c. 58) percent in 1957, and then 22.6 (c. 64) percent in 1960 (figure 17). Each peak was associated with a lull in new construction. The most significant was triggered by the outbreak of the Korean War on June 25, 1950, which trimmed production. Under Regulation X, the federal government limited funds for building; the cost of materials rose; and war-induced inflation raised interest and mortgage rates, which cut demand. By fall 1953, House and Home, the new self-appointed spokesman for the building industry, was arguing that “good housing for low income families can be provided much faster and cheaper by modernizing and rehabilitating existing homes than by new construction.” And, of course, men who had planned to settle down instead found themselves shipped overseas. In 1952, Mrs. Stefanick told Small Homes Guide that she and her husband had intended to build but that they had postponed their plans when he was called up. Meanwhile, like so many others, they made do with what they had.3

The Korean War affected Canada too. The Canadian government did not join this conflict immediately, and proportionately fewer Canadians fought there, but markets for money and materials were continental. Interest rates and building costs rose, and new construction dipped. As a result, after falling from 19 percent in 1944 to 9 percent in 1950, conversions and additions as a proportion of all new residential construction jumped to 12 percent in 1951 and stayed high for a couple of years. Even more than in America, these data underestimate the scale of improvement activity, including maintenance and repairs as well as the contribution of amateurs. But the subsequent peaks, in 1957 and 1960, and the longer-run trend were much the same. The Korean conflict brought the improvement peak forward, helping to raise its profile.4

A revival of home improvement was inevitable. Predictable stimuli include an increase in household size, especially when the original dwelling is small, and rising incomes. Both considerations were in play by the 1950s. New houses had been getting smaller for a generation. Those built in the 1920s and still standing in 1950 had, on average, 4.8 rooms, not counting the bath. Those from the 1930s had 4.6 rooms; falling to 4.4 between 1940–1944 and just 4.3 from 1945–1949. The typical postwar house had two bedrooms. The nadir was reached in 1949. In the second half of that year almost a third of all new single-family homes contained less than 800 square feet, and one in ten under 700. By 1951, the proportion of such small houses had halved, to 15 percent, and by 1955 had dropped to 7 percent. Responding to the shift, in 1956 the publishers of Small Homes Guide replaced “Small” with “New.” By previous or later standards, houses built in the first postwar decade were very small. As young couples moved in and started families, the need to remodel became pressing.5

Much of this activity was spontaneous. Maxine Livingstone at Parents Magazine gave an example. In suburban Chicago, the Newmans bought an older home that eventually proved too small, and so they modernized and built an addition. Families had always done this sort of thing. The new element was that many families were building or buying new homes that they knew would be insufficient. Parents Magazine featured “expandable homes” on the principle that “half a house is better than none.” Other publications, including Small Homes Guide (“Rags to Riches House—Expands Five Ways”) and Women’s Home Companion (“Small House Grows Up”), offered the same promise. This sort of promotion peaked in 1949, when new houses had never been smaller.6

Expandable homes were possible because cars enabled families to buy larger lots in distant suburbs where single-story dwellings were the norm. It was easy to add a room at the rear, or side. But there was a more familiar type of expansion that involved finishing a space within the existing shell, usually in the attic or basement. In older homes, space might be created when a dirty, coal-burning furnace was converted to oil or gas. In newer two-story homes, such expansions could be planned, as many builders knew. In Youngstown, Pennsylvania, for example, apart from erecting some National Homes “Thrift Houses,” the Cosmopolitan Housing Corporation produced conventional dwellings with unfinished attic space. The best-known, and best-documented, example of a builder who catered to this market was William Levitt. The houses that his company built in three U.S. Levittowns grew larger, rising from 750 square feet in 1947, to 800 in 1949, to 893 in 1953, and by the following year he was selling homes that ranged up to 2,000 square feet. Commonly, he left the “expansion attic” unfinished to keep prices low. As House and Home commented, “Bill Levitt isn’t even trying to guess how his buyers will use the second floor.” By then, Parents Magazine had already discussed the attic job that one family had undertaken in their Levittown Cape Cod. In a groundbreaking study of home improvement, Barbara Kelly has shown that this process—call it refinishing, expansion, or improvement—continued for decades, and began when families moved in. She notes that, as early as 1957, the New York Times reported that there was scarcely an unaltered Levitt house. Improvement was planned from day one and, with or without a wartime economy, would not be long delayed.7

Some builders produced a core house, with undefined potential. Others erected the sort of shell that had become popular during the 1930s, where it was not just the attic or basement that needed work. Buyers saved by delaying the installation of closets and cupboards, interior doors and partitions, and even plumbing. The potential of shells was recognized before the war ended. In March 1945, BSN reported that a Wisconsin dealer was erecting units that the buyer could “finish . . . as he wants over a period of years.” The retailer reckoned to “keep selling him the wallboard for his ceilings and sidings and his inside walls.” One such arrangement was promoted by H. R. Templeton, vice president of Cleveland Trust, and briefly head of the mortgage and savings division of the American Bankers Association. The scheme using Class 3 finance, had housed 500 families by 1950. An advantage of the shell was its flexibility. It attracted attention from Time, which noted that there might be “nothing inside but bare studding,” which also minimized upfront costs. At the other extreme, shells merged into Levitt-style cores. Some companies offered both, and everything in between. In Akron, Ohio, two dealers joined forces to start Skill-Craft Homes Inc., which offered eight versions of a 672 square foot (exterior dimensions) precut. Type A was a “roughed-in house including siding”; type B added interior trim, hardwood floor, and hardware; C added cupboards; D, rough plumbing; E, finished plumbing; F, heating; G, painting; H, spouting; and I, light fixtures. An extra room and porch were available as “accessories.” Precuts appealed to various buyers. In Maryland, the Prince Georges’ Development Corporation of Bladensburg erected them for large, speculative builders, small contractors, and amateurs. Design flexibility was shown by builder F. W. Stockton in Massachusetts. Working with the Beverly Co-operative Bank, he built shells as small as one-bedroom using a design that encouraged extension. Business flexibility was shown by Clarence Thompson, a dealer with four yards in central Illinois, who chaired the Lumber Dealers Research Council. He built conventional houses, usually on contract; marketed Lu-Re-Co preassembled walls to commercial builders; sold “finish-it-yourself” kits to owner-builders; and erected shell houses of various kinds. Precutting allowed many variations.8

Shells were produced at almost any scale. Towards the modest end of the spectrum, BSN reported that in Lisle, Illinois, a town of 2,500 located twenty-five miles west of Chicago, over a period of two years Hankinson Lumber supplied precut lumber and other material for seventeen shells to a local contractor. The dealer reckoned on supplying additional goods and services to the buyers, who would predictably make immediate improvements. At the other end, the largest operator may have been a truck driver in Florida who bought a shell house in 1946. Recognizing the business potential, he went into business with the builder, whom he bought out in 1948. By 1955, he had grown his business into the James Walter Corporation and was soon offering forty-five styles. At its peak, JWC employed 25,000 and acquired Celotex. From a business standpoint, the shell house clearly had potential.9

Whether as shells, or expandable cores, “customer-finished houses” were built in huge numbers for two decades after 1945. By 1961, in a survey of selected southern and midwestern states, William Shenkel found that shells alone accounted for 8 percent of housing starts. They invited, even compelled, improvement.10

A Nascent Improvement Industry

For a time after 1945, improvement was overshadowed by new construction. The imbalance was dramatized by Eric Hodgins, who in 1946 gave Mr. Blandings the choice of renovating an older home or building anew. The renovation failed, and so building from scratch dominated the story. Even so, publications such as Parents Magazine did run features on renovations and remodeling. Many focused on the challenges posed by homes dating from the 1920s, or before. The same was true of early improvement manuals such as William Crouse’s Home Guide to Repair, Upkeep, and Remodeling (1947), and Reginald Hawkins and C. H. Abbe’s New Houses from Old (1948). In tone, and in their assumption that owners would rely on contractors, these are similar to works published in the early 1930s. But, as soon as the downward share of improvement was reversed, the narrative changed.11

From 1950, trade journals jumped on the bandwagon. In 1951, Arthur Hood announced a quarterly supplement, Home Maintenance and Improvement, for readers of the American Lumberman. By 1954, BSN was relentless on the subject. That spring, it featured Annandale (Virginia) Millwork, which hired two “trouble shooters” to help owners with improvement projects. One had just finished building for himself. The manager claimed that “we sell more materials and make more money on home improvements to 10 homeowners than we do on materials sold to a builder for 50 houses.” The reason was the “the home owner sees the enormous possibilities in making his home more livable.” That fall, BSN surveyed three types of consumer business—home improvement, hobby, and sweat equity (i.e., owner-build)—and concluded that it was the first that had “greatest potential.” It was not simply a question of meeting demand. “More and more,” BSN claimed, “dealers are acquiring the knack of creating desire among their homeowners for the better ‘things’.” And they were the logical agents to take on this sort of marketing job. One survey showed that, when home owners thought about home remodeling, 70 percent turned first to the local retailer. Housing experts also acknowledged the fact. In 1955, Harvey Perloff, director of the planning program at the University of Chicago, offered advice as to how the adjacent Hyde Park–Kenwood neighborhood might take advantage of federal urban renewal funds in order to promote upgrading. He recommended that the community association help establish “well-equipped do-it-yourself stores in the area which would sell lumber, cement, paint and similar items . . . , rent out certain types of equipment and provide instructions.” For the good of the local community, as well as for himself, the local retailer was a useful agent of improvement.12

If retailers were important to home improvers, the reverse also became true. In 1957, BSN featured a “broad editorial program” called Operation Home Improvement. This consolidated what it was already doing, including the publication of hot tips, and underlined the fact the retailers were becoming dependent on this business. The point was soon made explicit. In an authoritative survey, Burnham Kelly suggested that “repair, rehabilitation, and modernization” had become “an extremely large market” and that “for many dealers this . . . provides the bulk of their sales.” His comments were echoed by others, notably Clark Row and Martin Meyerson. By 1962, Meyerson and associates reckoned that for “many suppliers . . . the modernization, maintenance and repair of the 58 million existing dwellings” was bigger business than their part in “the erection of the million or so new ones.” Ideally, the two markets were complementary: indoor improvements were tackled during the winter, when new construction flagged so that the former “helps to keep volume more or less steady.” By the standards of the building industry, home improvement was dependable, and soon had many retailers hooked.13

The same trend happened in Canada, but gathered momentum only after 1956. Lower real incomes probably account for the difference. Significantly, 1957 saw a flurry of activity. In early spring, speaking to the fortieth annual meeting of the Ontario Retail Lumber Dealer’s Association, president Tom Homewood (excellent name!) predicted that new construction might sag but that the improvement business would be “simply fantastic,” with a sales potential double that of new construction. Maclean-Hunter, the leading publisher of consumer and trade magazines, agreed. They launched a new journal for Canadian retailers, Building Supply Dealer, that was modeled on BSN. In the first issue, the editor noted the rapid rise since 1945 of all-purpose building retailers, while early articles emphasized direct selling to consumers for home remodeling.14

In the United States, the most important new trade journal was House and Home, which rapidly established itself as the spokesman for a building industry that was beginning to see real potential in the new market. As its first issue announced in January 1952, H&H was “conceived, written, and edited for professionals” by Henry Luce, publisher of Time and Life. It was an immediate hit. By May, subscriptions hit 100,000. That fall, the journal hosted the first of three round table conferences that were attended by representatives of all building industry groups, including the NRLDA and Producers’ Council. The resulting report, published in October, stated that “we do not believe the construction of cheap new houses is the best . . . answer to the need for better housing for low income families.” It rebutted public housing, an industry bugaboo, and argued that the “FHA should give property owners more help in financing improvement and rehabilitation costs.” It won widespread industry support, as indicated by letters it soon published. These included a response from FHA administrator Foley, who pointed to the successes of the Title I program—13 million loans to date—while conceding that more could be done. The National Association of Home Builders threw its hat into the ring, arguing that citizens and municipalities should promote rehabilitation to stem neighborhood decline, thereby creating “a new face for America.” Under industry pressure, in 1953 President Eisenhower appointed a twenty-three-person advisory committee that included thirteen who had attended one of the round tables. During its deliberations, H&H held its third round table, this time on property rehabilitation. It produced an action program that opened by declaring that “perhaps the most pressing challenge to private enterprise and the profit system in America today is the challenge to conserve and improve the 50 million homes in which we live.”15

Eisenhower’s committee submitted its report in December 1953. Summarizing it, in January 1954, H&H considered that it had “urged only one really sharp change of direction for federal housing.” This involved “rehabilitation and conservation,” now “the big new horizon of the housing market.” Those associated with the building industry threw their weight behind this idea. Notably, in the spring, NAREB established a Build America Better campaign, which soon included contests, run by local real estate boards, for “best improvement.” Eventually, after much wrangling, the Housing Act of 1954 delivered on this promise.16

The 1954 act included several provisions to limit scams, which had become a problem. Two decades earlier, the Title I program had given birth to itinerant entrepreneurs, especially roofers, with dubious business practices. The problem was that the FHA lacked staff. In the San Francisco office, one part-timer monitored contractors in a twenty-one-county area. He shuffled paper. The postwar boom expanded the problem. In spring 1946, BSN deplored the reappearance of high-pressure fly-by-nighters. By the 1950s a Consumer Reports exposé indicated the Title I program was “big enough to attract underworld talent.” Rackets became a scandal and, in fall 1953, the FHA cracked down by requiring new guarantees and paperwork. This did not eliminate the problem, and the 1954 Housing Act tackled it at its source. Henceforth, only approved lenders could make Title I loans, while luxury items such as pools and patios were excluded. More important, instead of insuring 90 percent of each lender’s portfolio the agency now restricted coverage to 90 percent of each loan. This encouraged lenders to exercise due diligence, rather than assume that on the average their funds were adequately covered. This set the program on a sounder footing, but reduced its appeal. Loans and funds insured under Title I declined rapidly from 1954.17

Even more importantly, the 1954 act recognized the open-end mortgage. In 1934, Title I financing had been cheaper than the alternatives; expandable homes and shells made it appear anachronistic and expensive. A Levitt home qualified for an FHA mortgage and so did some shells. Both loans were repayable at 5 percent over twenty years. But when the owner finished the interior, the best available rate was 9.6 percent, with repayment over two years. The difference in total monthly costs was considerable. And both were disadvantaged in comparison with the buyer of a larger, finished house, where the livable attic was financed by a mortgage, not a consumer loan. The executive vice president of the NRLDA illustrated the contrast. He estimated that a kitchen job costing $2,000 would add $21.22 to a mortgage that still had ten years to run but $63.80 if financed under Title I. This was arguably an inequity. Inarguably, the demand for home improvements was being inhibited. The prevalence of expandable and shell homes underlined how much business was being lost. And so pressure mounted for add-on mortgages that would allowed property owners to fund improvements by enlarging an existing loan. As one prominent lender put it, the open-end would be “singularly adaptable to the modernization of two-bedroom economy houses built in ’47 and ’48, many of which need repairs or additions.” And it promised to create business, for it would “allow the dealer to clinch a sale to a customer who otherwise would not modernize.”18

Outside the system of FHA insurance, the use of open-ended mortgages had grown rapidly from the late 1940s in response to demand. The amounts involved had risen from about $100 million in 1948 to $500 million in 1953, becoming comparable to sums insured under Title I. The open-end was recommended by magazines such as Small Homes Guide, home owners liked it, and savings and loans offered it, even before the U.S. Savings and Loan League gave its approval in summer 1952. An important step was taken early in 1953, when the Bank of America began to write mortgages with open-end provisions, but only because the Title Insurance and Trust Company insured them. This key development had great potential. As the executive vice president of Glendale (California) Federal Savings and Loan observed, “the open-end may well become the major consumer credit instrument of the next generation” because “it will establish the local mortgage lender as a permanent credit counselor to the small homeowner.” Endorsing this idea, Ernest Loebbecke, executive vice president of Title Insurance and Trust, pointed out that “there are no limitations on what the advances can be made for,” including “personal loans, durable goods, etc.” In effect, it merged various consumer loans and secured them on real estate. After the financial crisis of 2008–2009, we can see that this could open a can of worms, but in 1953 the building industry saw it as a great leap forward.19

House and Home made the open-end mortgage central to its campaign for property improvement. In summer 1952, it began a column on the “modern mortgage,” which corralled support for the savings and loans, the NAHB, the NRLDA, and Johns-Manville, a father of improvement finance. It allayed legal uncertainties by obtaining favorable opinion from previous counsel to the FHA and the HOLC. It argued that “the most frequently cited cause of home mortgage defaults since World War II has been the overextension of burdensome short-term debt,” a small problem that the open-end could address. Most tellingly, it pointed out that it would limit scams, since open-end arrangements would rely on lenders who routinely exercised due diligence. Consumer magazines added their voice, and when the president’s committee endorsed the open-end, H&H opened the champagne. This, it declared, “would have a significant effect on the economy of the nation.”20

In fact the effects of open-end mortgages were more modest. It did not eliminate rackets. A decade later, A. M. Watkins, the author of a manual on home remodeling, still perceived the need to include a cautionary chapter on the subject. Its effect on improvement financing was also limited. In 1963, House Beautiful published a special issue on remodeling that included an article on finance. In it, Miles Colean indicated six options, of which the open-end was only one, and not necessarily the most available. Many lenders still balked. One issue was how to accommodate changes in interest rates: how to add to a 5 percent mortgage when rates had risen to 7 percent? The problem was hardly insuperable, but it was messy and some lenders preferred to avoid it. Even so, Colean indicated that the open-end was probably the ideal, where available, and Watkins agreed.21

One of the least significant effects of the open-end mortgage, at least in the short run, attracted the most attention. The industry hoped that the 1954 act would nurture a larger and more reputable type of entrepreneur. In October, H&H declared that “the new Housing Act aims to underwrite a whole new market for modernisation,” and featured a rehabber and a builder (Fritz Burns) who were fixing up houses for resale. This belief drew inspiration from a civic initiative launched by the City of Baltimore in 1941. A housing bureau had been established in the city’s health department to promote code enforcement, slum clearance, and also rehabilitation. It worked well and attracted praise. In 1953, the city’s code inspector was made head of a new rehabilitation department at the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB). The same year, due to policy differences, several people resigned from the city’s bureau, including James Rouse, the chair, and Guy Hollyday, ex-president of the Mortgage Bankers’ Association, who was soon appointed FHA commissioner. Both Rouse and Hollyday served on Eisenhower’s housing committee, with Rouse chairing the subcommittee on rehabilitation. These Baltimore connections helped shape national policy.22

Indeed, efforts were made to corral municipalities with “big industry,” and to line both up behind the new federal housing program. In November 1954, President Eisenhower endorsed “a new, national, nonpartisan, non-profit organization” to promote neighborhood improvement. The board of the American Council to Improve our Neighborhoods (ACTION) included fifty-three men and women from manufacturing, labor, banking, building, religion, and women’s associations. General Electric, American Radiator, and Sears, Roebuck were prominent. Rouse soon took over as its president, while Albert Cole, HHFA administrator, attended its first meeting. The NRLDA was keen. The Advertising Council agreed to run a public service advertising campaign, which received pro bono cooperation from Young and Rubicam, while newspapers, magazines, and radio stations donated space or airtime. ACTION was soon sponsoring research into the improvement industry and the ways in which municipalities might help out.23

Prompted by its sponsors, ACTION threw its weight behind the goal, chimerical in the 1950s, of speculative rehabilitation. To some observers the idea of rehabilitating homes en masse made sense, and several companies supported it. In 1956, for example, U.S. Gypsum published Operative Remodeling jointly with the NAHB, proclaiming this to be “the new profit frontier for builders” and suggesting that speculative rehabilitation “has begun to step across the threshold of experimentation into the reality of grassroots practice.” A year later, ACTION supported and published William Nash’s Residential Rehabilitation. Private Profits and Public Purposes (1957), the first book-length work on the subject. It was groundbreaking, but its narrow focus limited its relevance. Focusing on speculative ventures in inner cities, it ignored the most typical sorts of improvements: small in scale, initiated by owners for their own benefit, and often carried out by them too. In business and cultural terms, it missed most of the action. In 1960, the authors of a careful survey of the field reported, in a careful understatement, that “the . . . feasibility of planned rehabilitation on a large scale basis has yet to be demonstrated.”24

Federal monies, coupled with the campaigns of NAREB and ACTION, persuaded many cities to act. To qualify for federal funding, each had to develop a “workable program” of urban renewal. In later years, this label became synonymous with slum clearance, but money was available for “conservation,” and cities were expected to identify which neighborhoods qualified for each type of assistance. In anticipation, in 1953 Detroit had initiated a conservation program for fifty-five middle-aged neighborhoods, which together housed a third of the city’s population. The following year, prompted by the Chicago Daily News, Chicago mounted a similar program and experimental scheme. By 1957, the New York Times reported that, in connection with NAREB’s campaign alone, 582 cities were addressing the slum problem by promoting neighborhood conservation.25

By then, manufacturers were vying for leadership of what had become a national movement. In 1955, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce conceived the idea of a promotional campaign named Operation Home Improvement. This brought together 500 businessmen, who spoke for 40 manufacturers in the home equipment field, and 27 from the building trades and financing. Their dual purpose was to promote business and prevent “unnecessary further expansion of the Government’s role in housing.” The group persuaded the HHFA to declare 1956 “Home Improvement Year,” and launched its campaign in January. It produced 25,000 advertising and display kits, and a forty-page handbook for local organizers. These proved to be spectacularly effective: within six months, groups had formed in more than one thousand cities. These comprised lumber dealers, contractors, lenders, and municipal officials. Taking a leaf from NAREB’s book, many planned model demonstration improvement projects, coupled with “considerable publicity.” The original idea had been for an eighteen-month campaign, but by February 1954, the group made the campaign “semi-permanent” and then, in July, established a permanent national council.26

Perhaps the timing of the OHI campaign was lucky, or perhaps the combined involvement of national manufacturers, together with local dealers and contractors, tipped the balance. Either way, 1956 was the year when a coherent, self-conscious home improvement industry was born. As a Times reporter observed about a group of Long Island improvement contractors that formed in that year, local industry groups were now doing “what many other business and professional associations have done when they realized that theirs was a major field of endeavor.” Having realized the improvement business was large, permanent, and distinctive, they had organized. It happened everywhere. Taking stock of the campaign’s first year, in February 1957, the national group met at the first National Improvement Congress in Tucson, Arizona. A reporter detected two main themes. First, that the “remodeling industry” had become a permanent and “independent entity,” one that was “not to be confused with ‘a substitute when new building drops off.’” Second, that “home betterment” was not just “a matter of property maintenance or a salvage operation[] to rescue aging houses from complete deterioration.” Repairs and, in specific neighborhoods, conservation were part of the picture, but improvement was a ubiquitous, and more ambitious, social practice. Many within the industry were pleasantly surprised to discover this. Those who organized the OHI campaign had not anticipated its success. In a sometimes fumbling way, a home improvement industry had finally been born.27

The Age of Do-It-Yourself

Paradoxically, the new home improvement industry depended on do-it-yourself. There is no way of knowing what proportion of improvement jobs in the 1940s and 1950s were being carried out by owners themselves, but surveys indicate it was substantial. In 1952, Popular Homecraft Magazine reported that among those readers who were undertaking home improvements, 85 percent did their own work. But what did this mean? That 85 percent were doing all of their own work, or just some? If just some, how much? And how typical were the magazine’s readers of home owners, or households, in general? A larger and more representative survey by the Georgia-Pacific Plywood Co. found that, depending on household income, 62–73 percent “are engaging in build-it-themselves additions or improvements.” But again, were these families doing all the work themselves? Surely not. Recent studies show that improvement jobs routinely combine paid with amateur labor. Perhaps the best we can do is echo Clark Row, who, from a close study of retailers in the early 1960s, concluded that do-it-yourself accounted for “probably over half” of all home improvement work.28

In any event, observers assumed that do-it-yourself was common, shells being a case in point. When Time discussed the subject in 1952, it entitled its article “Finish It Yourself.” In principle, of course, “finishing” could involve the use of hired labor, and occasionally this option was mentioned. In 1948, for example, BSN reported that Ham Lumber of Bradford, Massachusetts, was erecting shells that owners could finish themselves or employ contract labor. But most reports in the trade press show that the trade expected that owners would do most of the work themselves. Why else would the Johnson-Campbell Lumber Company of Fort Worth, Texas, emphasize that their two subdivisions of shell homes lay beyond city limits, where regulations did not mandate the use of accredited plumbers or electricians? Or why would an article on United Lumber of Cleveland in 1951 show Marion Potts finishing her shell home—moreover, one she had built herself? Or why would a Detroit shell builder give away a De Walt power saw to each buyer? Sometimes, as with Walker Brothers of Longview, Texas, the builders of shells reported that customers did their own finishing. Mostly they found it unnecessary. In the early 1960s, when William Shenkel carried out the first national survey of shells, he entitled his report to the HHFA “The Unfinished but Habitable Home.” When he published his results, however, he proclaimed the subject as “Self-Help Housing in the United States.”29

Do-it-yourself improvement was an extension of owner-building. For some individuals, such as Marion Potts, it was the next stage in the building process. In the aggregate, too, it gathered momentum as owner-building waned. Given that the two phenomena were so intimately related—requiring the same materials, tools, and skills; being undertaken by many of the same people; and being applied to many of the same structures—it is remarkable how consistently they have been treated as separate. Those, including myself in earlier work, who have written about owner-building have ignored improvement. Conversely, Carolyn Goldstein and Stephen Gelber, historians of do-it-yourself, have ignored the postwar boom in owner-building. They exaggerate a distinction that contemporaries made. Building suppliers and the trade press knew that amateur builders and improvers were, often literally, the same people. But the wider media ignored that fact. That is why it is important to trace not only the growth of amateur home improvement but also its social construction as do-it-yourself.30

The emergence of do-it-yourself had just happened. Since the 1920s, a growing number of property owners had been doing their own home repairs and maintenance. Such activity had always been most common among blue-collar workers, but its increase was fastest among the middle class. It was this group that, from the 1920s, had learned to value home ownership and then, during the Depression, found it necessary to do their own home repairs. Such work had been done mostly by the men, but the war compelled many women to learn repair skills too. By 1945, most Americans had come to assume that amateur improvement went with the territory of being a home owner.

Building suppliers had learned how to cater to this business, and continued to do so as it grew. One guesstimate claimed that lumberyard sales to home owners for all purposes increased 260 percent between 1939 and 1948. Trade journals continued to encourage the business. In 1947, for example, an American Lumberman survey alerted retailers to the fact that home owners were doing their own decorating and, in 1948, BSN featured a House Doctor service started by Restrick Lumber of Detroit to advise owners on improvement jobs. By 1950, such services were becoming common. In Chicago, for example, Edward Hines sponsored a weekly half-hour show on do-it-yourself. Running on Friday evenings, in preparation for the weekend, it claimed an audience of a quarter-million. By the following year, according to a later analysis in Printer’s Ink, do-it-yourself had become sufficiently large and coherent to be a “conscious market.” It went from strength to strength. By 1952, Dolan’s in Sacramento reckoned that for every 1,000 kits they sold, at least 3,000 materials orders came in for remodeling jobs. That fall, American Lumberman assembled a DIY advertising package for its retailer subscribers and enthused that “everything indicates that the do-it-yourself trend will increase indefinitely.” The next year brought proof. “Everywhere you go,” BSN declared in January 1953, “businessmen are talking about the amazing increase in do-it-yourself marketing.” Two years later, noting that do-it-yourself had grown by “leaps and bounds,” the NRLDA concluded that “it looks like a permanent business.” Home handymen had tracked the boom in home improvement after 1950—not surprisingly, since they had helped sustain it.31

Handy Men and Women

In fact do-it-yourselfers led the boom. They were driven by a slightly different mix of motives than homesteaders, for whom cost considerations were dominant. Only one published study considered what drove the amateur improver in the 1950s. Viron Hukill found that their main, if ill-defined, goal was “to add to the utility, worth and enjoyment of home.” Monetary considerations—including the attempt to avoid the high cost of building labor and to reduce the cost of living—mattered, but did not rank at the top.32

But were the same mix of motives present in all handymen? Arguably not. Writing in 1958, Albert Roland suggested that there were three types of handymen, distinguished more by purpose than income. The first and least common was the craftsman-hobbyist, the mainstay of local home workshop guilds in the 1930s. The second was the traditional handyman, typically a worker with a limited income, imbued with the “virtues of thrift and economic self-reliance.” Third was a newer and more affluent breed, who was not so much trying to save money as to stretch what he had as far it could go in order to “enhance living comfort and the looks of the home.” If the second type had to work on his home, the third chose to do so, a distinction recently made again by Colin Williams in his work on DIY in Britain. But Roland’s argument went further. Those driven by thrift could have afforded tradesmen if they had been willing to go into debt; conversely, those who chose to work on their homes did so because it was the only way “to upgrade their living standards” in a “consumption-oriented culture.” The difference, for Roland, was that they were aiming at luxury, not basic needs. Of course, what counted as a luxury in the 1950s—a bedroom for every family member! a second bathroom!—soon became an American norm. From that point of view, all do-it-yourselfers were simply trying to improve their standard of living. But for his time, Roland made the useful point that different people had different expectations but that both now saw do-it-yourself as a way of improving their living standards. This was new.33

Roland assumed that handymen treated do-it-yourself as a means to an end. What neither he nor Hukill discussed was the possibility that some men found the work intrinsically rewarding. Others, however, were convinced this was so. Some reckoned that the white-collar prejudice against manual labor was waning. A number, including Betty Pepis in the New York Times, attributed this to the war, when men from diverse backgrounds learned to enjoy physical labor. Others, including a writer in Harper’s (perhaps Frederick Allen, the editor) suggested that growing affluence and shorter work weeks were key. Distanced from an industrial past in a secure suburban prosperity, the modern white-collar worker felt free to labor, and enjoyed the leisure to do so. Home improvement then became a useful hobby. Indeed, Phil Creden, the advertising director for Edward Hines Lumber, suggested that by 1953 it had even “become smart to be handy.”34

But why? New social experiences allowed the stigma of labor to wane, but what made do-it-yourself happen? Two explanations were proposed, one appealing to the changing nature of work and the other to men’s changing family role. Both drew on pop psychology, and neither was grounded on much hard evidence; nevertheless, they should not be dismissed. They articulated wideheld beliefs. The first noted that much white-collar work had become bureaucratic and anonymous. The average employee was a cog; at the end of the working day he could not point with pride to anything distinctive that he had accomplished. Many factory workers had the same experience. As Paul Taylor put it, echoing Marx, workers had become alienated from the products of their own labor. They were way stations on an assembly line, or men in gray flannel suits. Then too, neither worker nor employee could choose when or how to work, or which tasks to tackle. Improvement projects were the opposite: an amateur could get tangible rewards from tasks he himself had set. As Taylor and others pointed out, handymen could take pride in their work, they could enjoy a “sense of accomplishment” (Time), “the feeling of creating something useful” (American Lumberman) or, as Hubbard Cobb told readers of his popular guide, “you can enjoy . . . the satisfaction derived from doing a job yourself—and doing it well.” Do-it-yourself was therapeutic, a term that many employed.35

If the modern workplace pushed men to find solace in home improvement, they were also pulled in this direction by the conviction that they could thereby contribute to family life. It was not just a question of saving money and raising living standards. The notion that work around the home had moral worth was not wholly new: improvement manuals published since the late 1920s had alluded to this possibility. But after 1945, it was articulated more forcefully and with greater conviction. In 1947, William Crouse wrote that “one of the joys as well as one of the obligations of being a householder lies in the performance of those services that a house must have to keep it in prime condition.” This still implied that the joys were separate from, and balanced by, responsibilities, but it soon gave way to a heartier endorsement. By 1952, J. E. Ratner, editor of Better Homes and Gardens, commented that “the home itself . . . is more of a hobby [for men] than it used to be.” In the Washington Post, Andrew Lang went so far as to claim that “[male] office workers in a huddle are more likely to be discussing the proper way to mix concrete than the curves of . . . Marilyn Monroe.” Possibly. But there was a point to be made. In The Big Change (1952), Frederick Allen at Harper’s connected the rise of do-it-yourself to a new informality in dress, manners, and, especially, relations between the sexes. One way of expressing this was to say, with H. M. Mueller, that his willingness to tackle odd jobs indicated how “domesticated” the American male had become, and some disapproved of the trend. Novelist John McPartland got a female character to declare that “all this do-it-yourself stuff, that’s like housework for men.” Disparaging the housewife as well as the domesticated man, it accurately expressed the concern, shared by many, that at home as well as at work men were being emasculated.36

But the dominant view of do-it-yourself was that it was acceptable to construction workers and morally good for family members, especially men. The most telling indicator is the fact that it received union support. One reason why some retailers were wary of chasing the consumer market was that they feared alienating their contractor customers (figure 56). To allay their concerns, the trade press often claimed that the two types of business were compatible. In 1952, for example, the American Lumberman argued that amateurs did the small jobs that tradesmen did not want, or took on projects that would not otherwise have happened. Similar arguments were widely expressed, for example in Printer’s Ink. The truth was more complex. Many building tradesmen were indeed concerned. In 1953, for example, the Painting and Decorating Contractors of America, who had been especially hard-hit by the rise of do-it-yourself, urged members to fight the trend by promoting the use of consumer loans. The campaign went local the following year. In Minneapolis, contractors and craftsmen joined a promotional effort to convince home owners that “the men with the professional knowhow can be counted on for superior work.” But in many localities, when the building trades asked industrial unions for their support they were rebuffed. As Ed Townsend reported in the Christian Science Monitor, “their [union] members . . . are enthusiastic ‘do-it-yourself’ devotees.” Support for do-it-yourself, then, crossed class boundaries. Indeed, by the mid-1950s it went beyond mere support. By 1957, being handy was coming to be expected, as David Dempsey suggested in the New York Times Magazine. Looking back, Steven Gelber has put it well: “By the 1950s,” he argued, “being handy had become, like sobriety and fidelity, an expected quality in a good husband.”37

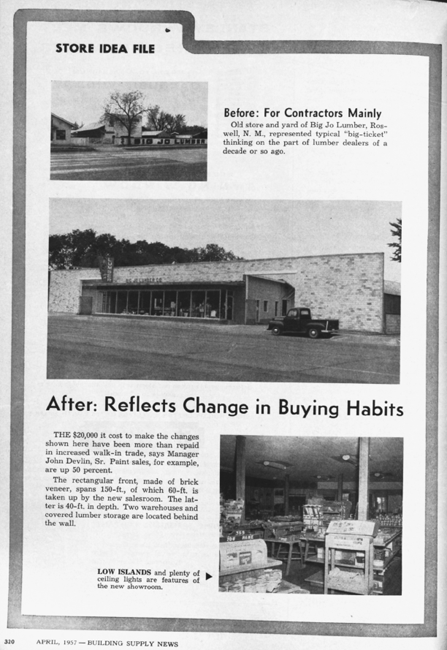

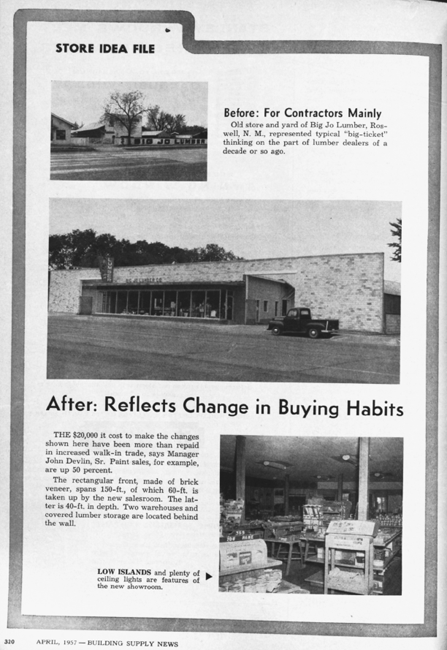

56. Contractors versus consumers. Many lumber dealers went after the new consumer business, but most continued to cater to contractors, often through a side entrance. Source: “Store Idea File,” Building Supply News 92, no. 4 (April 1957): 320.

For a time, the majority bought in to this view. Of course there was the stereotype of the harried husband, who had to be nagged to fix a leaky faucet, let alone remodel the bathroom. This image hovered over Life’s report about how well Don Brann’s Easi-Bild patterns were selling: it seems that 80 percent were bought by women, “partly because they believe their husbands can build something if they can’t afford to buy it.” Was it “can build” or “can be persuaded to build”? As Gelber puts it, capturing the spirit of a half-century of humorous birthday cards, “Handling heavy tools was man’s work; the woman’s job was to tell him what to do.” But there were plenty of men who welcomed domestic projects, especially if they got to choose which ones and if it allowed them to escape into their own workshop. After the early postwar fad for cheap, concrete slab construction, in 1954 Small Homes Guide noted that basements were “coming back,” in part because they accommodated a work bench. Having a workroom became important for many men. In 1964, the National Association of Home Builders hired a consultant to find out what features women wanted in their homes. In focus groups, many said they wanted a basement for their husband “do-it-yourselfer who now had a place for tools and a workshop.” Revealingly, a woman in Cincinnati observed, “I myself, wouldn’t want a basement, but my husband would, because men like to have a work shop and enjoy doing things.” The preference crossed class lines. An affluent woman in Los Angeles commented: “There is nothing better for the do-it-yourselfer. He can keep all his tools down there, and it’s locked. It’s not like a garage.” In many households, it was the man who most vigorously promoted do-it-yourself.38

But not all men joined the party. In 1954, Horace Greeley claimed that “94 percent of men are Mr. Fixits,” but the cliché of the harried husband had a basis in fact, surely more than 6 percent. The klutz had reason to balk. In 1954 alone, DIY’ers reported 600,000 injuries, not all minor. Even for professionals, construction could be risky, and power tools ratcheted up the risks. And there were plenty of men who enjoyed an evening or weekend of rest. As W. P. Patterson, director of the United States Bureau of Apprenticeship, growled in 1954: “It’s getting to the point with the ‘do-it-yourself’ business where you think a guy is a bum if he doesn’t come home after a day’s work and put in another six or eight hours fixing the house.” And perhaps most importantly, there had always been plenty of men, and women too, who were simply not very interested in their homes. Perhaps they had interesting jobs and did not need DIY therapy. Perhaps they looked for recreation and stimulation elsewhere. In 1959, Burnham Kelly reckoned this diverse group would remain large. “It is doubtful,” he suggested, “whether there will ever be a sizable market for housing to which a large amount of owner labor must be added, for the typical buyer wants his house as complete as possible.” It was partly for this reason, he suggested, that the postwar years had seen a growth in the large speculative builder. In the past, prospective owners had engaged contractors because they wanted a say in the design of the home. The modern consumer was content with an off-the-shelf unit. Kelly was overstating the point, but clearly there was a market for homes and improvements that did not involve the owner’s labor (figure 57). In 1964, for example, A. M. Watkins’ manual was explicitly directed at “the owner who wants to do it right—but not do it himself.” He argued that “it’s usually best to stick to your own profession,” and his publisher must have believed that many potential readers would agree. Men, then, were at least as diverse as retailers. Many lumber dealers chased the consumer trade, but not all. So it was with men. Most invested in do-it-yourself, but many found other ways to occupy their time.39

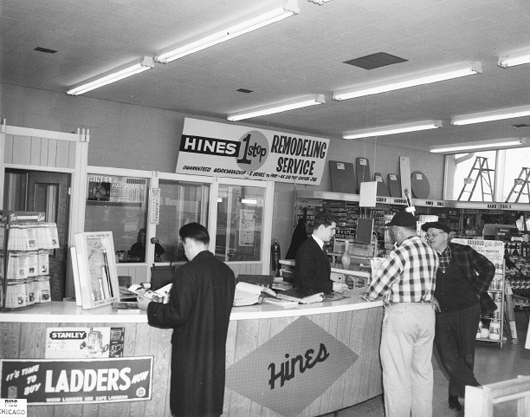

57. A professional improvement service. Dealers were pleased to cater to amateurs, but also to those who simply wanted to sign a check. Source: Edward Hines Lumber Co.

Overall, it is clear that after 1945 the motives for do-it-yourself were strong and growing. Virtually every contemporary discussion assumed that financial considerations were dominant. A good example was Enno Haan, former homecraft and technical editor of Popular Mechanics. His 1954 guide for remodelers listed three developments that had enabled men to become handy—war experience, educational manuals and magazines, and technical assistance from the industry—and two that were pushing them in that direction—a shortage a skilled labor and the cost of the labor that was available. As he put it, “a $75-per-week wage earner cannot afford to hire a $130-per-week professional.” For Haan, these considerations had brought about “a major revolution . . . among American homeowners.”40 And then there were the various intangible shifts in attitudes. None were well-documented, but certain facts seem clear. The stigma associated with manual work was on the decline, at least when undertaken voluntarily at home. There was a growing feeling among men that being handy provided some recompense for a routine jobs. And at least within the white-collar middle class, it was being recognized as a significant contribution to family life. Changing views about do-it-yourself helped shape the postwar home improvement industry.

Whatever the mix of motives, DIY did become increasingly common. Steven Gelber has suggested that, before World War II, less than a third of home owners did their own painting and wallpapering but that by the 1950s the ratio had risen to four in five. He may be correct, with most of the change happening after 1945. Telling information pertains to the period 1948–1952, when surveys showed that the proportion of householders who hung their own wallpaper had jumped from 28 percent to 60 percent. By the latter year, consumers were buying 60 percent of the wallpaper and 75 percent of the paint that retailers sold. Do-it-yourself was not making such rapid inroads into other lines of work. The Small Homes Guide survey of owner-builders found that, even by 1951, barely a third did plumbing, wiring, or glazing. But other indicators also hint at a disproportionate increase in handyman activity. Between 1946 and 1953, sales of power tools, increasingly targeted at the amateur, increased fifteen-fold. The growth of home improvement depended on the labors of a new generation of home owners.41

A Media Phenomenon

Consumer magazines and the general business press took a while to catch on to the trend. The first to do so was Better Homes and Gardens, which published its first Remodeling Ideas guide in 1949. Although the 1951 edition included an example of do-it-yourself, it did not use the phrase (figure 58). It was not until 1952 that Parents Magazine responded to the shift from building to modernizing. That summer, Small Homes Guide ran its first “special features on remodeling,” which focused on the needs of the amateur, and in 1953 it published its first survey of the materials and tools that he, or she, might need. The business press was just as slow. Printer’s Ink ran its first feature on the subject in March 1952, when it noted that “Mr. and Mrs. Fixit have become an important sales objective”; in June, Business Week analyzed the trend for a wider audience. Over the next two years, Ink published a series of articles that boosted and dissected what advertisers now realized was serious business. By 1953 Robert Bond at the Department of Commerce spoke of a distinct “do-it-yourself market,” to my knowledge the first time this phrase was used in print.42

58. Do-it-yourself crossed the boundaries of class and gender. But Better Homes and Gardens spoke to a class of female home owner who might have had second thoughts about heavy labor. Source: “The New Do-It-Yourself Business,” Business Week, June 14, 1952, 70.

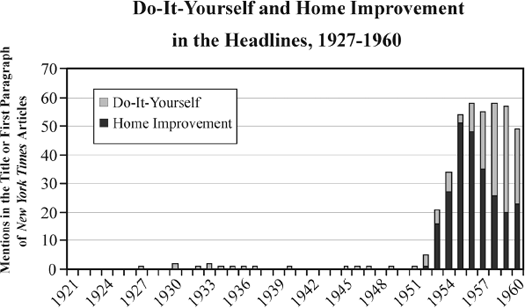

59. Do-it-yourself and home improvement in the headlines, 1927–60. Do-it-yourself took off suddenly in 1953, triggering a home improvement boom that had simmered for decades. Source: New York Times (historic online edition).

It was in 1953 that DIY caught the attention of the mass print media, this being triggered by the first trade show on March 16, 1953. Paradoxically, given the city’s low home ownership rate, and the restricted opportunities for amateur handiwork, this was held in New York. Featuring fifty-five manufacturers, it drew 65,000 visitors. Five months later, a show in Los Angeles ran twice as long and attracted four times as many, and that fall another was held in Chicago.43 Reporting on the New York show for Independent Woman, Lenore Hailparn reckoned it necessary to explain that DIY was “an industry which provides the tools and materials for those who want to do their own home decorating and repairing.” Soon, reporters realized that they could dispense with the gloss. In May, the Washington Post assured readers that the “urge to swing a hammer isn’t a passing fancy”; without explanation, in September, Life offered their portrait of Don Brann as “the do-it-yourself man”; a month later Harper’s Magazine proclaimed that DIY was “now fashionable”; and in December the Christian Science Monitor described how companies were cashing in on the trend. From nowhere, do-it-yourself had become a fad. The first story in the New York Times to mention “do-it-yourself” in the title or first paragraph ran in 1952. There was just one. In 1953, there were seventeen (figure 59).44

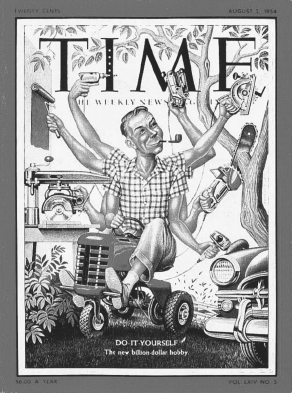

60. Do-it-yourself arrives. Time’s cover for August 2, 1954, set the seal of approval on a fad-cum-social-norm that had arrived on the scene the previous year.

The story was now feeding on itself. In the early 1950s, on the first Sunday of each year, the New York Times ran stories on topics that had “brought the greatest number of inquiries during the past twelve months.” On January 3, 1954, it noted that father’s workbench was replacing the ping-pong table in the basement. “Possibly the most noticeable tendency of the American public,” it commented, “and one developing at an increasing pace, was the intense interest in anything related to the ‘do-it-yourself’ fad.” Except, the writer went on to say, it was “more than a fad . . . America’s latest recreation.” Media coverage was ramped up. Newspapers such as the Christian Science Monitor covered New York’s second DIY show, which was bigger and better than the first; the Times saw fit to print the thoughts about DIY of Paul Collyer, executive vice president of the Northeastern Retail Lumbermen’s Association, when he spoke to regional delegates. By the summer, hardware stores were planning a fall do-it-yourself month, and in August 1954, Time put do-it-yourself on its cover and proclaimed it “the new billion-dollar hobby” (figure 60). It had become mainstream, with 475 newspapers nationwide carrying regular DIY sections by 1957.45

Carolyn Goldstein has commented that DIY happened “seemingly overnight.” “Seeming” is right. In the mass media it happened in the second half of 1953; in consumer magazines and the business press it had happened in 1952; but in the trade press and on the ground it had been happening for some time, arguably as long ago as the Depression years, and as far back as the 1920s if you pushed the argument. As Harold Rosenberg grumbled in August 1954, in response to Time’s cover, BSN had been pushing do-it-yourself for “years before anybody but lumber merchants knew such activity was important.” Like most overnight sensations, do-it-yourself had been years in the making. In only one sense did things happen suddenly, and it was important. Until the fall of 1953, amateurs did not know they were engaged in do-it-yourself. The media did not create the trend, but they fashioned the phenomenon that made a market.46

We may speculate that, after 1953, as home owners learned to think of themselves as handymen, they became more inclined to fill that role. Social expectations come from many sources, but the media are important. After reading a newspaper story that millions of other Americans were improving their standard of living, and that of their loved ones, by finishing basements and building extensions, a man might yawn and turn on the TV. But, equally, the story might firm up his vague resolve to build the closet, or repair the screen door, that his wife had been going on about for several weeks. What we loosely refer to as consumer demand was reinforced, and shaped, by being reflected back upon itself.

Manufacturing the Change

Demand was also molded more actively by those companies that had a stake. The boom in owner-building and do-it-yourself took manufacturers by surprise. This was even true of Delta, which had marketed tools for children in the 1920s and prided itself on being consumer savvy. But they and their competitors soon learned, if only by serendipity. Reynolds Metals provides an interesting example. When its vice president of sales development noticed a carpenter using a crosscut saw on some of his company’s aluminum trim molding he was surprised to learn that this did not damage the saw. He began advertising this fact in a sales campaign directed at home handymen: you don’t even need to buy a new tool to use our product. The boom in owner-building had given companies like Reynolds a heads up, and by the time DIY hit its stride, Printer’s Ink reported that manufacturers had learned to shape the market. They were advertising, certainly, but also designing products and changing methods of distribution to satisfy a new class of buyer.47

At an increasing pace after 1945, manufacturers brought new materials to market, and packaged them in new ways too. Prime examples were the manufacturers of paint and wallpaper. Companies developed resin (1942), and then latex emulsion (1949) paints that dried quickly and were easier to clean up after. Rollers, previously used by professionals, made painting wall surfaces much quicker and were eagerly adopted by amateurs. Pre-pasted wallpaper was introduced in the early 1940s and improved with slow-drying preparations that waited while amateurs fumbled. Some clever innovations did not catch on. Wall-Dec introduced 14” squares of wallpaper that were easier to install, but which flopped, probably because they left too many tell-tale joins. But innovative materials clearly stimulated some of the increase in amateur home decoration in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The manufacturers of plywood, previously sold in unwieldy 4’ × 8’ sheets, brought out smaller “handy panels” that were an instant success. Other companies introduced ranges of linoleum, vinyl, and asphalt floor tiles. David Kennedy, president of Kentile, claimed to have pioneered sales to do-it-yourselfers, and by 1954 reckoned that this business had become “a permanent part of the American economy.” He was right: by 1957, half of all floor tiles were being sold to amateurs. His company felt so sure of the user-friendliness of its product that it advertised to “Mrs. Fixit.” Manufacturers were transferring knowledge from the installer to the product. A paperhanger or tile-setter would once have learned how to quickly spread a thin, even layer of adhesive. Self-adhesive wallpaper and tiles did the same thing. And so Hachmeister, another manufacturer of floor coverings, could boast: “We guarantee your work.”48

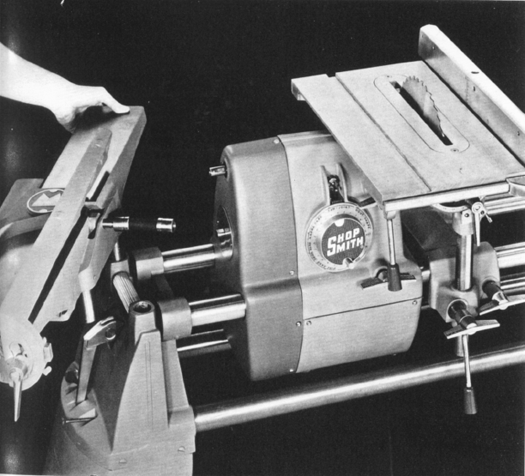

The most influential products designed for the amateur were hand and power tools. The most impressive was the Shopsmith, a multipurpose bench tool. Although expensive, and initially intended for professionals, its early sales were encouraging. The manufacturer, Magna Engineering, adapted it for consumers by “making it look more like a clean, functional home appliance than a gray-iron power tool” (figure 61). It changed speed control labels from rpm’s to “saw,” “rout,” and “drill,” and covered moving parts to make it safer. This allayed the apprehensions of wives, skeptical of the abilities of their ten-thumbed husbands. Within six years, Magna had sold 150,000 units. The Shopsmith was the adaptable workhorse of a home workshop; the Black and Decker drill and a variety of power saws were the more nimble assistants of handyman, from Paul Corey downwards (figure 62). Black and Decker made an unusually early pitch for the consumer, bringing out a line of portable tools in 1946. Their Home-Utility ¼” drill was the first to be designed for consumers. A million were bought within five years, making it the leading symbol of the handyman craze. Stanley were only a step behind. Their tool division, established in 1937, was expanded in 1950 to produce a new line of Handyman tools, including the Steelmaster hammer and Surform shaper. The latter, a company history later declared, was a new product “ideal for Do-It-Yourselfers since it could be used to file, trim and cut a wide variety of materials, including wood, asphalt tiles, brass and even mild steel.” More generally, in 1953, Stanley’s annual report declared that “promotion of our hardware and tools sales has sought to take full advantage of the current ‘Do-It-Yourself’ vogue and the growing importance of the ‘Home Workshop’ idea.”49

61. The do-it-yourselfer’s state-of-the-art. The versatile Shopsmith, adapted for amateurs, became the definitive home workshop tool in the early 1950s. Source: “Power Tools: The Newest Home Appliance,” Industrial Design 1, no. 1 (February 1954): 34; “Do It and You,” Industrial Design 1, no. 4 (August 1954): 88.

Marketing became more sophisticated. An early example was the Formica Company, of Cincinnati. Established in the 1910s, Formica had expertise in producing decorative plastic laminates. Installation in stores and then dwellings was done by professionals. Observing the new consumer market, in 1948 Formica began advertising in home service magazines, such as Small Homes Guide, and when one of its early ads produced 16,000 inquiries the company was “rocked back on its heels.” It developed a new adhesive, sold as Formica Bond Cement, that enabled “anyone with reasonable skill and armed with simple woodworking tools” to install Formica with “an ordinary rolling pin.” Sales soared. Soon the process of product development became seamless. At Stanley, Ken Freedell, general manager of the tools division, played a key role. At his instigation, in 1956 a marketing department was established “to guide the Sales Department,” and changed the company’s game plan. Instead of promoting the products that its engineers had developed, it began to research “what customers wanted” and then told “new-product engineers [to] fill those needs.”50

62. Paul Corey using a power saw in building a Cemesto house. Saws could be used not only on wood but also, as here, on wallboard. Source: Papers of Paul Corey. MsC 585 (Iowa author), Special Collections, University of Iowa Libraries.

Some new products required new methods of distribution. This might involve no more than careful tweaking. Freedell introduced a Profitool display program to its existing network of retailers. It showed hand tools in a standard format that “encourag[ed] browsing and impulse purchases.” In 1962, this was updated to a Uni-Rack display, installed in traveling vans to showcase the product line to the dealer. But sometimes the manufacturer had to rethink its whole distribution system. Having one outlet in each major market made sense when you sold to contractors, but it was inconvenient for consumers. And so, for example, Sherwin-Williams abandoned its network of exclusive dealerships and distributed more widely. This type of switch had to be managed so as not to alienate contractors. When Formica changed to a wider pattern of retail distribution in the late 1940s, it nurtured its image among retailers by advertising in the key trade journals, Flooring, BSN, and American Lumberman. It argued that Formica was a product worth carrying. At the same time, it placated commercial fabricators. The challenge was to retain a group of professionals on whose loyalty the company still depended. It argued that the new do-it-yourself campaign was “directed to a market they cannot serve anyway.” In a rapidly growing market, companies could finesse resistance.51

Manufacturers learned to work more closely with retailers. Of course, they continued to speak directly to consumers through mass advertising. Formica increased its advertising budget fourfold in five years; by 1953 the Douglas Fir Plywood Association was advertising in 1,626 newspapers, in addition to specialized and popular magazines such as Popular Mechanics and Life. But companies also fostered retailers. In 1954, Black and Decker designed a display package that enabled retailers to provide a Do-It-Yourself Headquarters. To sell the idea, company salesmen did “one night stands at dealer meetings in towns coast to coast.” Along with other tool manufacturers, it offered a rental program that included agreement forms and instruction books to accompany displays and promotional material. Three years later, Carr, Adams and Collier, makers of BILT-WELL Woodwork, told dealers that it had developed “a powerful 8 phase integrated merchandising plan designed to substantially increase your sales.” This included national and local (cooperative) advertising, displays, direct mailings, “calculating devices,” a data book, illuminated signs, and a cabinet training program for dealer salesmen. Except for the rental scheme, none of this was original: Johns-Manville had pioneered training and education in the 1930s, and dealer “helps had been around since the 1920s. But now all companies were doing something along these lines. Kaiser Aluminum helped retailers sell the company’s roll-on roofing and flashing with a direct mail program, advertising mats, building plans, a free booklet, and display racks. The Philip Carey Mfg. Co., makers of Carey Spun Rock Wool insulation, offered a “complete sales promotion kit” to “the builder and ‘do-it-yourself’ markets,” which included radio spots as well as the usual paraphernalia. The exceptional had become the norm.52

The most original element in the marketing schemes of manufacturers after 1945 was their willingness to learn from the retailer. Before the war, marketing was top-down. Arthur Hood had assumed that Johns-Manville should guide and instruct its dealers. This made sense, because most dealers were lagging behind consumer demand. But the owner-building boom had changed the dynamic. Being on the front line, retailers had responded to the sweat equity market just as quickly than the manufacturers. In particular, they had grasped the fact that amateurs needed hands-on help. On this matter, for the first time in the irregular ascent of amateur home improvement, retailers showed the way.

House Doctors

In the late 1940s, retailers had learned how to serve the owner-builder. They had diversified, built showrooms, and relocated to well-trafficked streets. When the sweat equity business waned, they used their new facilities to promote the home handyman business. In 1954, BSN offered a now-familiar checklist of “basic tips”: price by the package, or a unit of measurement that consumers would understand, not the board foot; encourage cash-and-carry or a monthly plan, such as Title I, rather than the open account; rent tools, as well as car-top carriers; on large orders, offer a discount for “self-delivery”; but, “first and foremost,” extend your business hours. It went without saying that dealers should advertise. As John Egan, Hoo Hoo’s Grand Snark, observed with lumberman’s humor to the middle-Atlantic dealers in 1954, “doing business without advertising is like winking at a girl in the dark. You know what you’re doing but nobody else does.” It also went without saying that dealers had to be prepared to handle the car as well as the consumer, since “most of business is self pickup on weekends.” This meant ample parking, and Neiman-Reed of Van Nuys, California, was praised for rearranging its yard to accommodate drive-in service. Such companies were large enough to use TV (for its “prestige value”—those were the days!), as well as innovative ways of bringing materials to the consumer’s attention. One employee, for example, “created a lucrative sideline in the form of a mobile demonstration unit for Shopsmith equipment,” deployed on evenings and weekends. These were the sorts of methods that dealers had already adopted to serve the owner-builder.53

Familiar too was the attention lavished on the female customer. Women played an even larger role in home improvements than in owner-building since many of these affected the interior, woman’s domain. Indeed, many projects were devised by the woman of the household. Manufacturers learned to make tools safer, and also more visually appealing, especially when they realized that many were bought by wives as presents. Retailers were even more alert. As Frank Tutt, general manager of Prescott Lumber of Prescott, Arizona, commented in 1950, “Every woman is a good paint prospect.” Not just paint. In 1954, a survey of U.S. Plywood customers found “a large population of husbands and wives together” and “a significant proportion of women alone.” In contrast, “only a minority of men were solely responsible for the buying decisions.” And the woman would spread the word better than the man. As Gates Ferguson, director of promotion and advertising for Celotex, observed in 1954, “If she doesn’t get the kind of service she is entitled to, all the girls know about it before the sun sets that night.” As he put it, “The three fastest methods of communications are still telephone, telegraph, and tella woman.” But that principle had an upside for a store that gave good service.54

And so dealers went further to appeal to women. In Tulsa, Oklahoma, Foster Lumber designed an eighty-foot display room with women in mind, offering instruction in the use of tools so that women could complete jobs their husbands had “promised to do but [had] overlooked.” By 1955, Neiman-Reed was offering what BSN reckoned to be “the first known power tool and woodwork school for women.” Thirty had signed up, and another thirty were on the waiting list for a second class. This was linked to a fashion show staged in a boxcar that demonstrated “what the well-dressed handy-woman will wear.” TV was brought into play. During Gates Ferguson’s illustrated talk in 1955, he challenged the advertising caption “Ladies Do It Yourself.” He suggested that at best it might encourage the wife to get the husband to help fix something. Retailers knew better. Chairman Art Hood noted that in Oklahoma City a new Here’s How daytime TV show was directed exclusively at women. He reported that too many listeners’ letters complained about the service women received in local stores. That may be, but retailers now knew who they had to satisfy in order to succeed in the DIY market.55

By the early 1950s, retailers were becoming involved in publisher tie-ins that indicate that the DIY market was becoming coherent. As they had done for owner-builders, publishers produced manuals for the handyman improver. Popular Mechanics produced a general Handyman’s Guide (1951) and another that offered suggestions for Planning Your Home Workshop (1949) and Getting Started with Power Tools (1957). Family Handyman, begun in 1950, published suggestions about How to Double the Living Space in Your Home (1955) as well as 400 Quick Answers to Home Repair and Improvement Problems (1955). Many other guides were produced. Better Homes and Gardens published two editions of Remodeling Ideas (1949, 1951), Samuel Paul prepared The Complete Book of Home Modernizing (1953) just as DIY was going viral while a laggard, American Builder, suggested How to Remodel Your Home (1958). But the best-seller was BHG’s Handyman’s Book (1951), intended for “the average man who putters around.” (“Handyman projects” could be “a whale of a lot of fun . . . you are your own boss.”) The key feature was that retailers and the publisher developed a joint promotional program. Dealers carried the book and used it to sell materials and packages. In 1953, BSN reported that the manager of Iltis Lumber of Des Moines had noticed that, after buying BHG’s book, many customers would return to buy materials or set up a home workshop. Like other consumer magazines, including Small Homes Guide and Parents Magazine, BHG used its letters page and surveys to learn about its readers. It asked what projects they were doing, and then taught them how to do it. It developed a similarly close relationship with retailers. It produced sales helps, a promotional package that included newspaper mats and banners, and gave notice of upcoming features and advertising so that retailers could arrange tie-in promotions. Dealers and other publishers nurtured a relationship, for example at dealer conventions. These had long been attended by editors of trade journals, but now also by those with consumer magazines. In 1950, for example, Joseph Mason from Good Housekeeping told members of the Mid-Atlantic Lumber Dealers’ Association that he received about 150,000 letters a year about building and improvement, almost all answerable by a dealer. Five years later, advertising manager Lee Adams reassured the same audience that “we at Popular Science feel a close kinship with the building supply dealer”: both were educating DIY’ers. Dealers had learned to cooperate with manufacturers, and now with publishers.56

The BHG tie-in was untypical, but not unique. In 1955, McCall’s launched a promotional campaign that included the distribution of woodworking patterns and contacted retail distributors. In the Pittsburgh area, these included a department store and a hardware store. The idea was that these would run demonstrations, but it turned out that neither was well-equipped. Mark Lumber stepped in, offering to do demos and also supply the other retailers with the packages of wood that customers would need. Such arrangements may not have been the norm, but they were probably common.57

Retailers also developed new ways of cooperating with manufacturers of tools and materials. An especially effective service for owner-builders had been to provide hands-on instruction, and this was a natural for the improvement market too. The reason that Mark Lumber got the McCall’s job was that they had run do-it-yourself classes the previous year. Attendances had reached 400 one evening, 45 percent of whom were women. Similarly, Neiman-Reed employed a high school industrial arts teacher to host its weekly TV show and ran six-week classes on basic home repairs. In 1954, Time enthused about a hardware store that was holding this type of clinic, but lumber dealers had been doing it for years. In Blue Island, Illinois, for example, Mathieu Lumber graduated from owner-builder to handyman classes, and by 1954 Blue Island Lumber was doing the same. Some again employed “field instructors,” “counselors,” or “outside salesmen”—job titles varied. In Iowa City, Schoeneman Lumber started a Handy Andy service, in which an instructor made house visits to show how to do remodeling work. If the owner ran into difficulties, the dealer had a roster of contractors that it could call upon. As Charlottesville (Virginia) Lumber discovered, in combination with in-store classes, such services “paid off handsomely.” By 1954, dealers were reporting “enormous interest” in them.58