Linguistics has familiarized us with concepts like “minimum vocalism” and “minimum consonantism” which refer to systems of oppositions between phonemes of so elementary a nature that every known or unknown language supposes them; they are in fact also the first oppositions to appear in the child’s language, and the last to disappear in the speech of people affected by certain forms of aphasia.

The two concepts are moreover not really distinct, since, according to linguists, for every language the fundamental opposition is that between consonant and vowel. The subsequent distinctions among vowels and among consonants result from the application to these derived areas of such contrasts as compact and diffuse, open and closed, acute and grave.

Hence, in all the languages of the world, complex systems of oppositions among phonemes do nothing but elaborate in multiple directions a simpler system common to them all: the contrast between consonant and vowel which, by the workings of a double opposition between compact and diffuse, acute and grave, produces on the one hand what has been called the “vowel triangle”:1

a

u i

and on the other hand the “consonant triangle”:

k

p t

It would seem that the methodological principle which inspires such distinctions is transposable to other domains, notably that of cooking which, it has never been suf- ficiently emphasized, is with language a truly universal form of human activity: if there is no society without a language, nor is there any which does not cook in some manner at least some of its food.

We will start from the hypothesis that this activity supposes a system which is located—according to very difficult modalities in function of the particular cultures one wants to consider—within a triangular semantic field whose three points correspond respectively to the categories of the raw, the cooked and the rotted. It is clear that in respect to cooking the raw constitutes the unmarked pole, while the other two poles are strongly marked, but in different directions: indeed, the cooked is a cultural transformation of the raw, whereas the rotted is a natural transformation. Underlying our original triangle, there is hence a double opposition between elaborated/unelaborated on the one hand, and culture/nature on the other.

No doubt these notions constitute empty forms: they teach us nothing about the cooking of any specific society, since only observation can tell us what each one means by “raw,” “cooked” and “rotted,” and we can suppose that it will not be the same for all. Italian cuisine has recently taught us to eat crudités rawer than any in traditional French cooking, thereby determining an enlargement of the category of the raw. And we know from some incidents that followed the Allied landings in 1944 that American soldiers conceived the category of the rotted in more extended fashion than we, since the odor given off by Norman cheese dairies seemed to them the smell of corpses, and occasionally prompted them to destroy the dairies.

Consequently, the culinary triangle delimits a semantic field, but from the outside. This is moreover true of the linguistic triangles as well, since there are no phonemes a, i, u (or k, p, t) in general, and these ideal positions must be occupied, in each language, by the particular phonemes whose distinctive natures are closest to those for which we first gave a symbolic representation: thus we have a sort of concrete triangle inscribed within the abstract triangle. In any cuisine, nothing is simply cooked, but must be cooked in one fashion or another. Nor is there any condition of pure rawness: only certain foods can really be eaten raw, and then only if they have been selected, washed, pared or cut, or even seasoned. Rotting, too, is only allowed to take place in certain specific ways, either spontaneous or controlled.

Let us now consider, for those cuisines whose categories are relatively well-known, the different modes of cooking. There are certainly two principal modes, attested in innumerable societies by myths and rites which emphasize their contrast: the roasted and the boiled. In what does their difference consist? Roasted food is directly exposed to the fire; with the fire it realizes an unmediated conjunction, whereas boiled food is doubly mediated, by the water in which it is immersed, and by the receptacle that holds both water and food.

On two grounds, then, one can say that the roasted is on the side of nature, the boiled on the side of culture: literally, because boiling requires the use of a receptacle, a cultural object; symbolically, in as much as culture is a mediation of the relations between man and the world, and boiling demands a mediation (by water) of the relation between food and fire which is absent in roasting.

The natives of New Caledonia feel this contrast with particular vividness: “Formerly,” relates M. J. Barrau, “they only grilled and roasted, they only ‘burned’ as the natives now say... The use of a pot and the consumption of boiled tubers are looked upon with pride... as a proof of... civilization.”

A text of Aristotle, cited by Salomon Reinach (Cultes, Mythes, Religions, V, p. 63), indicates that the Greeks also thought that “in ancient times, men roasted everything.” Behind the opposition between roasted and boiled, then, we do in fact find, as we postulated at the outset, the opposition between nature and culture. It remains to discover the other fundamental opposition which we put forth: that between elaborated and unelaborated.

In this respect, observation establishes a double affinity: the roasted with the raw, that is to say the unelaborated, and the boiled with the rotted, which is one of the two modes of the elaborated. The affinity of the roasted with the raw comes from the fact that it is never uniformly cooked, whether this be on all sides, or on the outside and the inside. A myth of the Wyandot Indians well evokes what might be called the paradox of the roasted: the Creator struck fire, and ordered the first man to skewer a piece of meat on a stick and roast it. But man was so ignorant that he left the meat on the fire until it was black on one side, and still raw on the other... Similarly, the Poconachi of Mexico interpret the roasted as a compromise between the raw and the burned. After the universal fire, they relate, that which had not been burned became white, that which had been burned turned black, and what had only been singed turned red. This explanation accounts for the various colors of corn and beans. In British Guiana, the Waiwai sorcerer must respect two taboos, one directed at roast meat, the other red paint, and this again puts the roasted on the side of blood and the raw.

If boiling is superior to roasting, notes Aristotle, it is because it takes away the rawness of meat, “roast meats being rawer and drier than boiled meats” (quoted by Reinach, loc. cit.).

As for the boiled, its affinity with the rotted is attested in numerous European languages by such locutions as pot pourri, olla podrida, denoting different sorts of meat seasoned and cooked together with vegetables; and in German, zu Brei zerkochetes Fleisch, “meat rotted from cooking.” American Indian languages emphasize the same affinity, and it is significant that this should be so especially in those tribes that show a strong taste for gamey meat, to the point of preferring, for example, the flesh of a dead animal whose carcass has been washed down by the stream to that of a freshly killed buffalo. In the Dakota language, the same stem connotes putrefaction and the fact of boiling pieces of meat together with some additive.

These distinctions are far from exhausting the richness and complexity of the contrast between roasted and boiled. The boiled is cooked within a receptacle, while the roasted is cooked from without: the former thus evokes the concave, the latter the convex. Also the boiled can most often be ascribed to what might be called an “endo-cuisine,” prepared for domestic use, destined to a small closed group, while the roasted belongs to “exo-cuisine,” that which one offers to guests. Formerly in France, boiled chicken was for the family meal, while roasted meat was for the banquet (and marked its culminating point, served as it was after the boiled meats and vegetables of the first course, and accompanied by “extraordinary fruits” such as melons, oranges, olives and capers).

The same opposition is found, differently formulated, in exotic societies. The extremely primitive Guayaki of Paraguay roast all their game, except when they prepare the meat destined for the rites which determine the name of a new child: this meat must be boiled. The Caingang of Brazil prohibit boiled meat for the widow and widower, and also for anyone who has murdered an enemy. In all these cases, prescription of the boiled accompanies a tightening, prescription of the roasted a loosening of familial or social ties.

Following this line of argument, one could infer that cannibalism (which by definition is an endo-cuisine in respect to the human race) ordinarily employs boiling rather than roasting, and that the cases where bodies are roasted—cases vouched for by ethnographic literature—must be more frequent in exo-cannibalism (eating the body of an enemy) than in endo-cannibalism (eating a relative). It would be interesting to carry out statistical research on this point.

Sometimes, too, as is often the case in America, and doubtless elsewhere, the roasted and the boiled will have respective affinities with life in the bush (outside the village community) and sedentary life (inside the village). From this comes a subsidiary association of the roasted with men, the boiled with women. This is notably the case with the Trumai, the Yagua and the Jivaro of South America, and with the Ingalik of Alaska. Or else the relation is reversed: the Assiniboin, on the northern plains of North America, reserve the preparation of boiled food for men engaged in a war expedition, while the women in the villages never use receptacles, and only roast their meat. There are some indications that in certain Eastern European countries one can find the same inversion of affinities between roasted and boiled and feminine and masculine.

The existence of these inverted systems naturally poses a problem, and leads one to think that the axes of opposition are still more numerous than one suspected, and that the peoples where these inversions exist refer to axes different from those we at first singled out. For example, boiling conserves entirely the meat and its juices, whereas roasting is accompanied by destruction and loss. One connotes economy, the other prodigality; the former is plebeian, the latter aristocratic. This aspect takes on primary importance in societies which prescribe differences of status among individuals or groups. In the ancient Maori, says Prytz-Johansen, a noble could himself roast his food, but he avoided all contact with the steaming oven, which was left to the slaves and women of low birth. Thus, when pots and pans were introduced by the whites, they seemed infected utensils; a striking inversion of the attitude which we remarked in the New Caledonians.

These differences in appraisal of the boiled and the roasted, dependent on the democratic or aristocratic perspective of the group, can also be found in the Western tradition. The democratic Encyclopedia of Diderot and d’Alembert goes in for a veritable apology of the boiled: “Boiled meat is one of the most succulent and nourishing foods known to man... One could say that boiled meat is to other dishes as bread is to other kinds of nourishment” (Article “Bouilli”). A half-century later, the dandy Brillat- Savarin will take precisely the opposite view: “We professors never eat boiled meat out of respect for principle, and because we have pronounced ex cathedra this incontestable truth: boiled meat is flesh without its juice... This truth is beginning to become accepted, and boiled meat has disappeared in truly elegant dinners; it has been replaced by a roast filet, a turbot, or a matelote” (Physiologie du goût, VI, 2).

Therefore if the Czechs see in boiled meat a man’s nourishment, it is perhaps because their traditional society was of a much more democratic character than that of their Slavonic and Polish neighbors. One could interpret in the same manner distinctions made—respectively by the Greeks, and the Romans and the Hebrews—on the basis of attitudes toward roasted and boiled, distinctions which have been noted by M. Piganiol in a recent article (“Le rôti et le bouilli,” A Pedro Bosch-Gimpera, Mexico City, 1963).

Other societies make use of the same opposition in a completely different direction. Because boiling takes place without loss of substance, and within a complete enclosure, it is eminently apt to symbolize cosmic totality. In Guiana as well as in the Great Lakes region, it is thought that if the pot where game is boiling were to overflow even a little bit, all the animals of the species being cooked would migrate, and the hunter would catch nothing more. The boiled is life, the roasted death. Does not world folklore offer innumerable examples of the cauldron of immortality? But there has never been a spit of immortality. A Cree Indian rite admirably expresses this character of cosmic totality ascribed to boiled food. According to them, the first man was commanded by the Creator to boil the first berries gathered each season. The cup containing the berries was first presented to the sun, that it might fulfill its office and ripen the berries; then the cup was lifted to the thunder, whence rain is expected; finally the cup was lowered toward the earth, in prayer that it bring forth its fruits.

Hence we rejoin the symbolism of the most distant Indo-European past, as it has been reconstructed by Georges Dumézil: “To Mitra belongs that which breaks of itself, that which is cooked in steam, that which is well sacrificed, milk... and to Varuna that which is cut with the axe, that which is snatched from the fire, that which is ill-sacrificed, the intoxicating soma” (Les dieux des Germains, p. 60). It is not a little surprising—but highly significant—to find intact in genial mid-nineteenth-century philosophers of cuisine a consciousness of the same contrast between knowledge and inspiration, serenity and violence, measure and lack of measure, still symbolized by the opposition of the boiled and the roasted: “One becomes a cook but one is born a roaster” (Brillat-Savarin); “Roasting is at the same time nothing, and an immensity” (Marquis de Cussy).

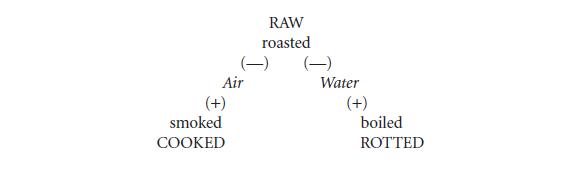

Within the basic culinary triangle formed by the categories of raw, cooked and rotted, we have, then, inscribed two terms which are situated: one, the roasted, in the vicinity of the raw; the other, the boiled, near the rotted. We are lacking a third term, illustrating the concrete form of cooking showing the greatest affinity to the abstract category of the cooked. This form seems to us to be smoking, which like roasting implies an unmediated operation (without receptacle and without water) but differs from roasting in that it is, like boiling, a slow form of cooking, both uniform and penetrating in depth.

Let us try to determine the place of this new term in our system of opposition. In the technique of smoking, as in that of roasting, nothing is interposed between meat and fire except air. But the difference between the two techniques comes from the fact that in one the layer of air is reduced to a minimum, whereas in the other it is brought to a maximum. To smoke game, the American Indians (in whose culinary system smoking occupies a particularly important place) construct a wooden frame (a buccan) about five feet high, on top of which they place the meat, while underneath they light a very small fire which is kept burning for forty-eight hours or more. Hence for one constant—the presence of a layer of air—we note two differentials which are expressed by the opposition close/distant and rapid/slow. A third differential is created by the absence of a utensil in the case of roasting (any stick doing the work of a spit), since the buccan is a constructed framework, that is, a cultural object.

In this last respect, smoking is related to boiling, which also requires a cultural means, the receptacle. But between these two utensils a remarkable difference appears, or more accurately, is instituted by the culture precisely in order, it seems, to create the opposition, which without such a difference might have remained too ill-defined to take on meaning. Pots and pans are carefully cared for and preserved utensils, which one cleans and puts away after use in order to make them serve their purpose as many times as possible; but the buccan must be destroyed immediately after use, otherwise the animal will avenge itself, and come in turn to smoke the huntsman. Such, at least, is the belief of those same natives of Guiana whose other symmetrical belief we have already noted: that a poorly conducted boiling, during which the cauldron overflowed, would bring the inverse punishment, flight of the quarry, which the huntsman would no longer succeed in overtaking. On the other hand, as we have already indicated, it is clear that the boiled is opposed both to the smoked and the roasted in respect to the presence or absence of water.

But let us come back for a moment to the opposition between a perishable and a durable utensil which we found in Guiana in connection with smoking and boiling. It will allow us to resolve an apparent difficulty in our system, one which doubtless has not escaped the reader. At the start we characterized one of the oppositions between the roasted and the boiled as reflecting that between nature and culture. Later, however, we proposed an affinity between the boiled and the rotted, the latter defined as the elaboration of the raw by natural means. Is it not contradictory that a cultural method should lead to a natural result? To put it in other terms, what, philosophically, will be the value of the invention of pottery (and hence of culture) if the native’s system associates boiling and putrefaction, which is the condition that raw food cannot help but reach spontaneously in the state of nature?

The same type of paradox is implied by the problematics of smoking as formulated by the natives of Guiana. On the one hand, smoking, of all the modes of cooking, comes closest to the abstract category of the cooked; and—since the opposition between raw and cooked is homologous to that between nature and culture—it represents the most “cultural” form of cooking (and also that most esteemed among the natives). And yet, on the other hand, its cultural means, the buccan, is to be immediately destroyed. There is striking parallel to boiling, a method whose cultural means (the receptacles) are preserved, but which is itself assimilated to a sort of process of auto-annihilation, since its definitive result is at least verbally equivalent to that putrefaction which cooking should prevent or retard.

What is the profound sense of this parallelism? In so-called primitive societies, cooking by water and smoking have this in common: one as to its means, the other as to its results, is marked by duration. Cooking by water operates by means of receptacles made of pottery (or of wood with peoples who do not know about pottery, but boil water by immersing hot stones in it): in all cases these receptacles are cared for and repaired, sometimes passed on from generation to generation, and they number among the most durable cultural objects. As for smoking, it gives food that resists spoiling incomparably longer than that cooked by any other method. Everything transpires as if the lasting possession of a cultural acquisition entailed, sometimes in the ritual realm, sometimes in the mythic, a concession made in return to nature: when the result is durable, the means must be precarious, and vice-versa.

This ambiguity, which marks similarly, but in different directions, both the smoked and the boiled, is that same ambiguity which we already know to be inherent to the roasted. Burned on one side and raw on the other, or grilled outside, raw within, the roasted incarnates the ambiguity of the raw and the cooked, of nature and culture, which the smoked and the boiled must illustrate in their turn for the structure to be coherent. But what forces them into this pattern is not purely a reason of form: hence the system demonstrates that the art of cooking is not located entirely on the side of culture. Adapting itself to the exigencies of the body, and determined in its modes by the way man’s insertion in nature operates in different parts of the world, placed then between nature and culture, cooking rather represents their necessary articulation. It partakes of both domains, and projects this duality on each of its manifestations.

But it cannot always do so in the same manner. The ambiguity of the roasted is intrinsic, that of the smoked and the boiled extrinsic, since it does not derive from things themselves, but from the way one speaks about them or behaves toward them. For here again a distinction becomes necessary: the quality of naturalness which language confers upon boiled food is purely metaphorical: the “boiled” is not the “spoiled”; it simply resembles it. Inversely, the transfiguration of the smoked into a natural entity does not result from the nonexistence of the buccan, the cultural instrument, but from its voluntary destruction. This transfiguration is thus on the order of metonymy, since it consists in acting as if the effect were really the cause. Consequently, even when the structure is added to or transformed to overcome a disequilibrium, it is only at the price of a new disequilibrium which manifests itself in another domain. To this ineluctable dissymmetry the structure owes its ability to engender myth, which is nothing other than an effort to correct or hide its inherent dissymmetry.

To conclude, let us return to our culinary triangle. Within it we traced another triangle representing recipes, at least the most elementary ones: roasting, boiling and smoking. The smoked and the boiled are opposed as to the nature of the intermediate element between fire and food, which is either air or water. The smoked and the roasted are opposed by the smaller or larger place given to the element air; and the roasted and the boiled by the presence or absence of water. The boundary between nature and culture, which one can imagine as parallel to either the axis of air or the axis of water, puts the roasted and the smoked on the side of nature, the boiled on the side of culture as to means; or, as to results, the smoked on the side of culture, the roasted and the boiled on the side of nature:

The operational value of our diagram would be very restricted did it not lend itself to all the transformations necessary to admit other categories of cooking. In a culinary system where the category of the roasted is divided into roasted and grilled, it is the latter term (connoting the lesser distance of meat from fire) which will be situated at the apex of the recipe triangle, the roasted then being placed, still on the air-axis, halfway between the grilled and the smoked. We may proceed in similar fashion if the culinary system in question makes a distinction between cooking with water and cooking with steam; the latter, where the water is at a distance from the food, will be located halfway between the boiled and the smoked.

A more complex transformation will be necessary to introduce the category of the fried. A tetrahedron will replace the recipe triangle, making it possible to raise a third axis, that of oil, in addition to those of air and water. The grilled will remain at the apex, but in the middle of the edge joining smoked and fried one can place roastedin-the-oven (with the addition of fat), which is opposed to roasted-on-the-spit (without this addition). Similarly, on the edge running from fried to boiled will be braising (in a base of water and fat), opposed to steaming (without fat, and at a distance from the water). The plan can be still further developed, if necessary, by addition of the opposition between animal and vegetable foodstuffs (if they entail differentiating methods of cooking), and by the distinction of vegetable foods into cereals and legumes, since unlike the former (which one can simply grill), the latter cannot be cooked without water or fat, or both (unless one were to let the cereals ferment, which requires water but excluded fire during the process of transformation). Finally, seasonings will take their place in the system according to the combinations permitted or excluded with a given type of food.

After elaborating our diagram so as to integrate all the characteristics of a given culinary system (and no doubt there are other factors of a diachronic rather than a synchronic nature; those concerning the order, the presentation and the gestures of the meal), it will be necessary to seek the most economical manner of orienting it as a grille, so that it can be superposed on other contrasts of a sociological, economic, esthetic or religious nature: men and women, family and society, village and bush, economy and prodigality, nobility and commonality, sacred and profane, etc. Thus we can hope to discover for each specific case how the cooking of a society is a language in which it unconsciously translates its structure—or else resigns itself, still unconsciously, to revealing its contradictions.