2. Early Conservation Photography

“Conservation photography is as much about what a photographer does with the photo—what that photo is used for after it is taken—as it is about the subject or beauty of the image itself.” —Morgan Heim, conservation photographer

In 1803, the Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of a young America. Although the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804–1806 mapped a portion of it, the region remained largely wild and unknown. For the next few decades, it became the domain of fur trappers and mountain men—some of whom brought back wild tales of a place called Yellowstone where the ground spewed steaming geysers and ferocious grizzly bears roamed. At that time, a few photographic processes had been devised (the Daguerreotype and later tintypes), but these were impractical to use outside a special studio. It wasn’t until the 1850s that the collodion wet-plate process, which could be used more readily in the field, was invented.

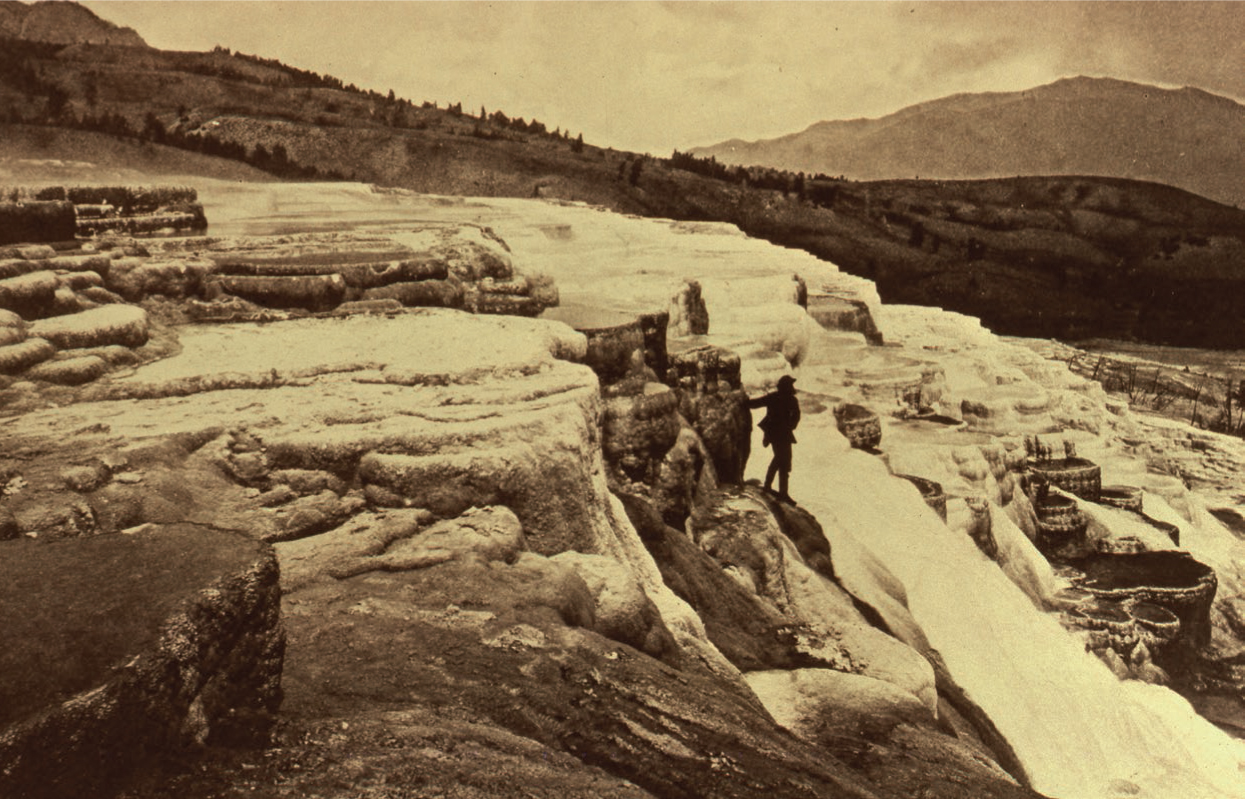

In 1869, William Henry Jackson (an early practitioner of the collodion process) was commissioned by the Union Pacific Railroad to photograph the scenery along the newly completed transcontinental railroad, promoting tourism and travel. Subsequently, his photographs drew the attention of Ferdinand V. Hayden, director of a U.S. government survey charged with documenting the geology, flora, and fauna of the mysterious Yellowstone region. Impressed with Jackson’s work, Hayden invited him to join an expedition in 1870.

The trip presented substantial challenges. In the more remote areas, transportation was by pack mule. With cameras, wooden tripods, tents, glass plates, and chemicals, Jackson’s equipment weighed over 300 pounds. Actually, Jackson was quite proud that he could pare it down to a mere 300 pounds.

Additionally, the wet-plate process required large glass plates be coated with a light-sensitive emulsion that was prepared fresh for each photograph—something that was not easy under the field conditions that Jackson encountered. The exposure and subsequent development of the negative image then had to be carried out before the moist emulsion dried. Otherwise, the plate lost its sensitivity. In the dry Rocky Mountain air, Jackson had to work quickly.

William Henry Jackson’s equipment consisted of all the chemicals and glass plates used in the wet-plate process. The tent served as a portable darkroom for coating the plates and developing the images. The tent was yellow-lined to filter out light from the blue end of the spectrum, to which the orthochromatic emulsion was primarily sensitive. Photo courtesy of Scotts Bluff National Monument.

Finally, there was the challenge of making each exposure. There were no light meters at the time; exposures were determined by experience. Besides the need to work quickly, the sensitivity of the emulsion was appallingly slow. Based on exposure data I found in Jackson’s autobiography Time Exposure (a very appropriate title, by the way), I roughly calculated the equivalent ISO speed to be just 0.1 to 0.5! On your digital camera, an ISO setting of 100 is 1000 times faster than Jackson’s wet-plate emulsion at 0.1 ISO. “Time exposure” indeed. Jackson wrote that many of his exposures in bright sunlight were on the order of 5 seconds—and much longer if he stopped his lens down for maximum depth of field. You can well imagine how long the exposures were on overcast days.

Jackson returned to the Yellowstone region in 1871 with the Hayden survey and continued his documentation. With him on this trip was the famed artist Thomas Moran. Upon their return east that fall, Jackson learned that Congress was contemplating passage of a bill to make Yellowstone a national park. In late February the following year he went to Washington and it was his photographs, along with Moran’s marvelous paintings, that helped assure passage of the bill by revealing the wonders of Yellowstone to some indifferent congressmen. Yellowstone became the world’s first national park on March 1, 1872—and Jackson, unknowingly, became the second conservation photographer.

Though Jackson’s work is often credited with protecting Yellowstone, Carleton Watkins had been photographing Yosemite Valley more than 10 years before Jackson’s visit there. In fact, Watkins’ photographs of the grandeur of the valley prompted the U.S. Congress to pass legislation in 1864 to protect the valley, along with the adjacent grove of giant sequoias. While Yosemite was not technically a national park at that point (because the protected lands were ceded to California as a state park), we should credit Watkins as being possibly the first conservation photographer.

Among the pioneer photographers, Watkins’ work has been overshadowed by Jackson’s—and only in recent years has the importance of his photos been recognized. Watkins also used the wet-plate collodion process, but his glass plate negatives were a colossal 18×22 inches! He referred to his camera as a “mammoth.”

Sadly, Watkins lost many of his early negatives in a financial crisis (he had to sell his negatives to another photographer who later took credit for them). His remaining life’s work was later destroyed by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fires. All that remained were prints made from those original negatives.

Jackson’s photo of the travertine terraces at Mammoth Hot Springs was among the many images, along with Thomas Moran’s paintings, that convinced Congress to establish Yellowstone National Park in 1872. Moran is the figure in the photo. Public domain photo.

Carleton Watkins photographed Yosemite Valley in the early 1860s, and his photographs were largely responsible for the U.S. Congress to pass legislation protecting Yosemite, though it was initially established as a state park rather than a national park. Public domain photo.

The Impact of Film Photography

The era of the wet-plate process ended in the 1880s with the invention of the dry plate, later perfected and marketed by George Eastman. This eliminated the need for carrying chemicals (and the associated equipment) and made for a more mobile means of travel into remote regions. Through the early 20th century, better films and smaller, easier-to-use cameras brought photography into the hands of more people. Serious documentation continued, and by the middle of the 20th century documentary photography blossomed.

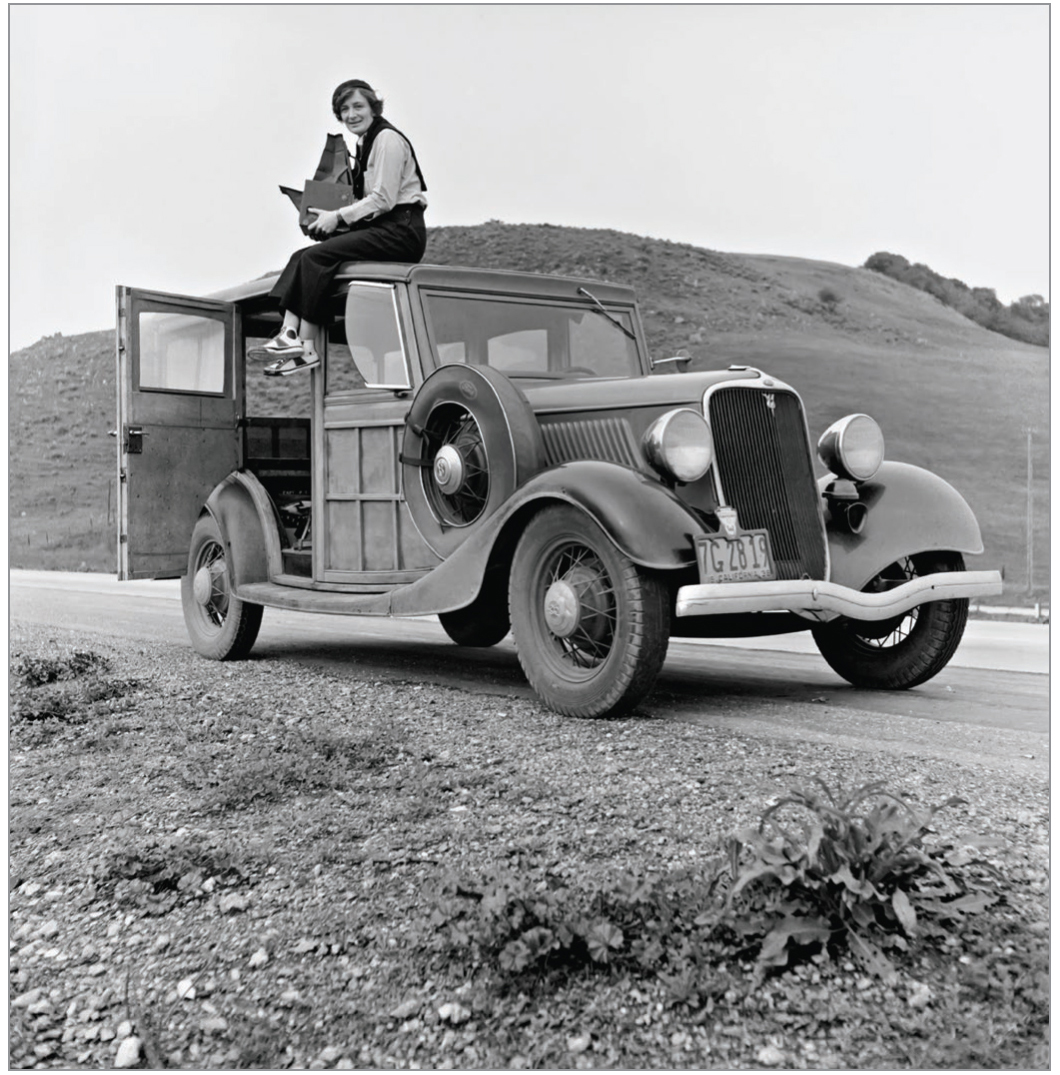

Among the more famous of the FSA photographers was Dorothea Lange. Many of her photos were made using a bulky 4×5-inch Graflex single-lens-reflex camera. Public domain photo.

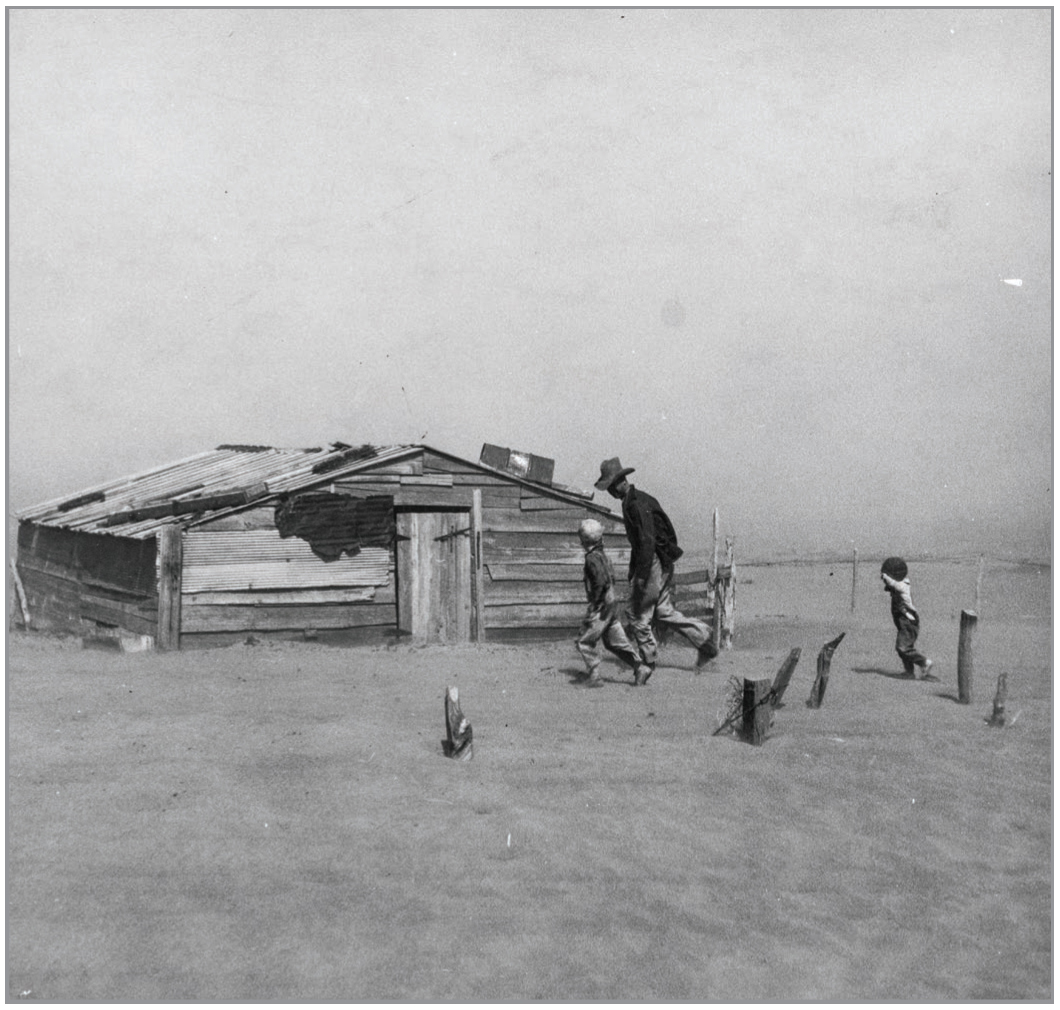

Arthur Rothstein was one of the FSA photographers. His best-known photo was this one made in a dust storm in Oklahoma. Public domain photo.

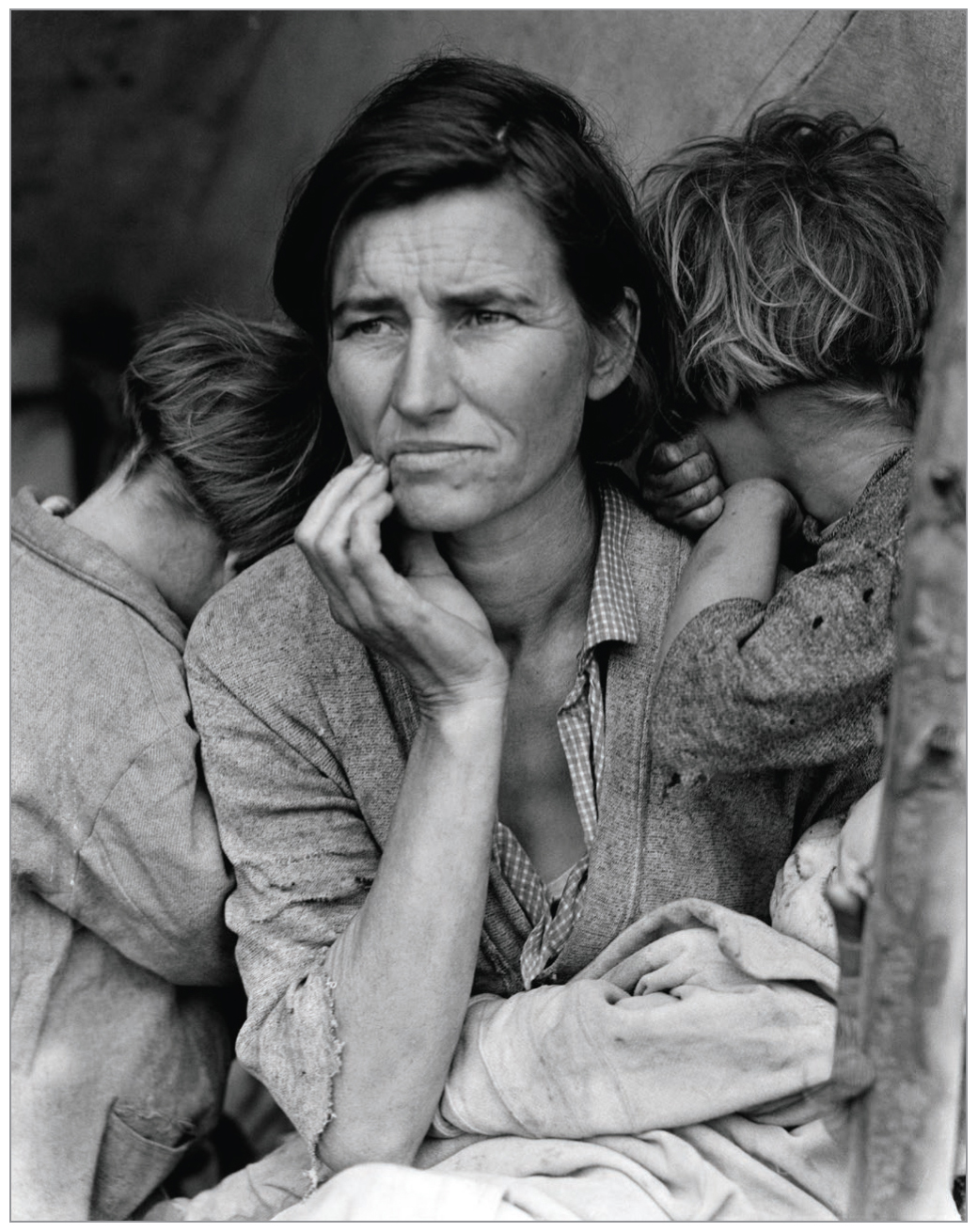

Perhaps the most iconic photo of the FSA program was Dorothea Lange’s picture of a migrant mother in the heart of the Great Depression years. Public domain photo.

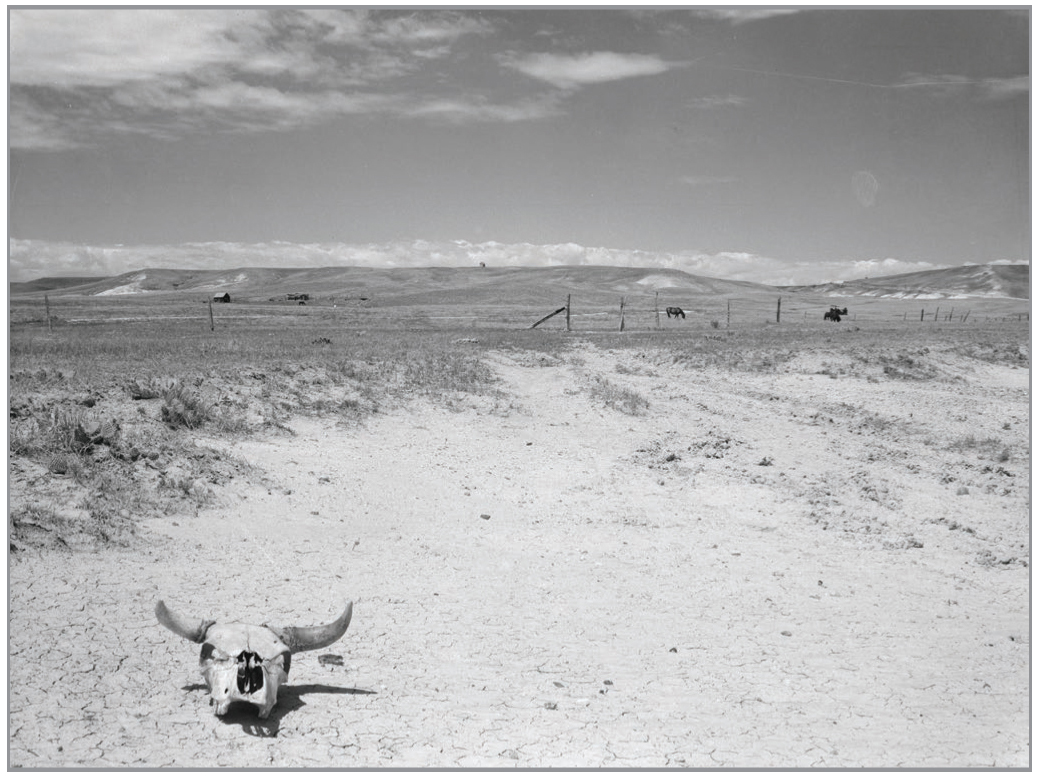

Arthur Rothstein documented the combined ravages of overgrazing and drought in South Dakota. Public domain photo.

Perhaps the greatest documentary photography project of all time in this nation was started by the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in the 1930s. It recorded the disastrous effects of drought and economic depression of that decade. This was not a conservation photography program. Rather, it was intended to document the human condition and the poverty brought on by the depression. However, much of the work did include the environmental damage of the dust bowl and other regions ravaged by drought. In addition, many of the photographs depicted landscapes in various parts of the country that today serve as points of comparison for environmental changes.

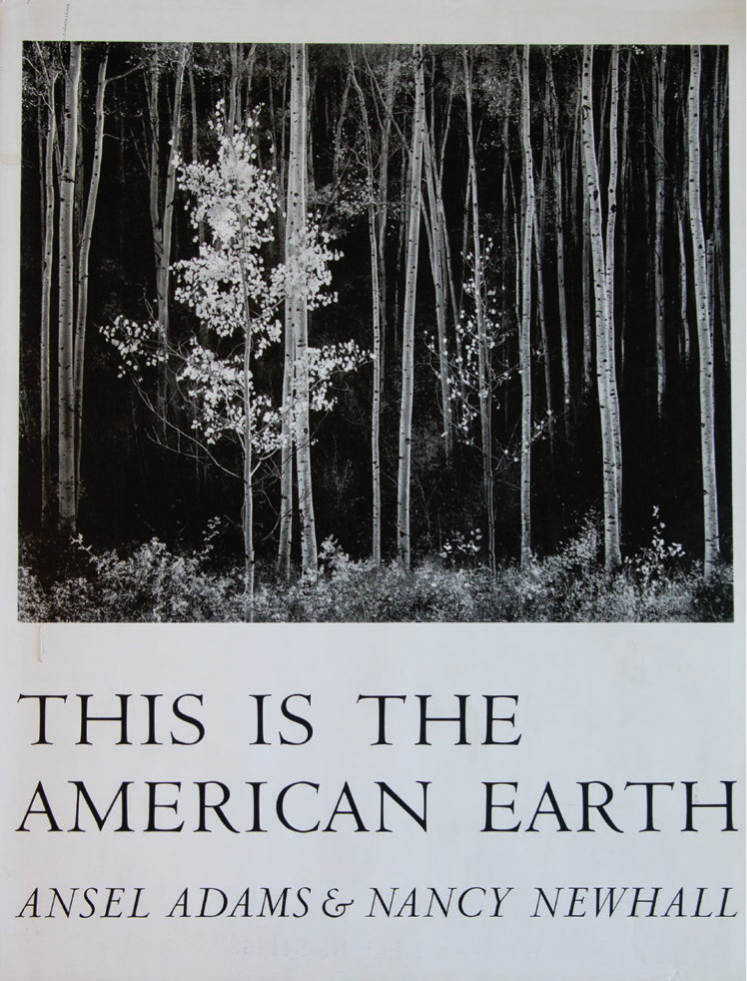

One of the first Sierra Club Exhibit Format books featured Ansel Adams’ exquisite black & white photographs. Courtesy of the Sierra Club.

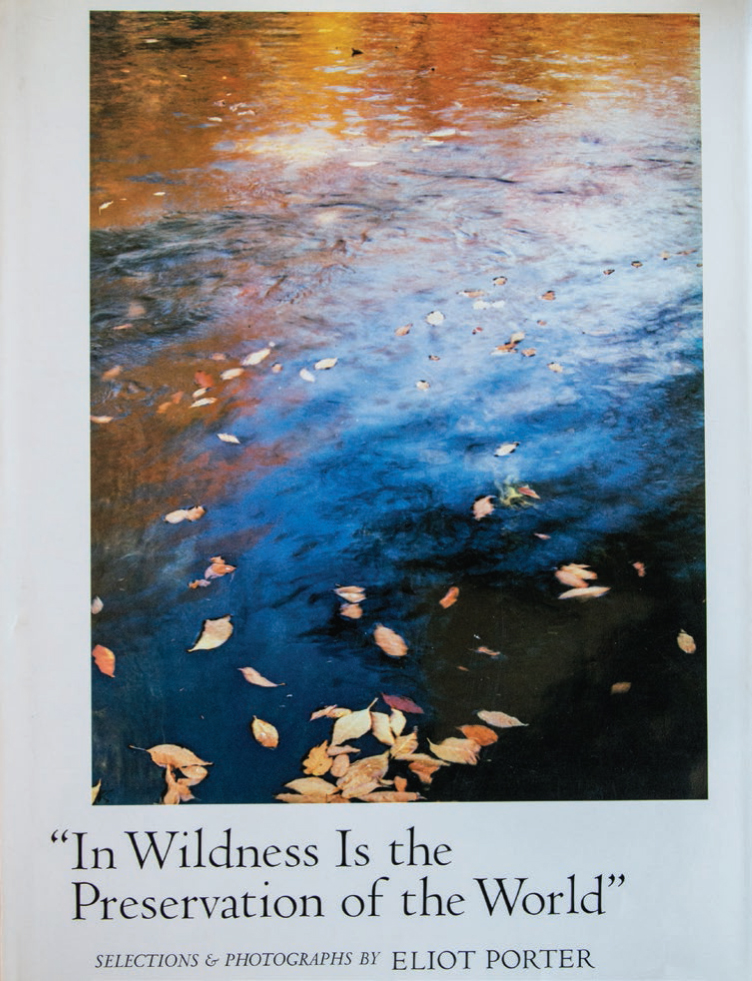

The all-time best seller of the Exhibit Format books was Eliot Porter’s In Wildness Is the Preservation of the World with quotations from Henry David Thoreau. Courtesy of the Sierra Club.

Eleven photographers came to work on this project, many of them achieving fame through their images. Most of the participating photographers worked with cumbersome large format cameras using mostly black & white film. Among the many iconic images, those created by Dorothea Lange and Arthur Rothstein are perhaps the most famous. The FSA visual archive, some 175,000 photos in the Library of Congress, is a vital record that we, as photographers, can learn much from.

Publishing Spreads the Message

Fast forward to 1960 and the era of David Brower, then executive director of the Sierra Club. As a staunch defender of wild lands, Brower recognized the power of photography in shaping public opinion. He launched a publishing program of large, lavishly printed books he called the Exhibit Format series. These books were a grand departure from picture books of the day, in which smaller pages and multiple images on each page helped reduce printing costs.

Brower’s philosophy was that each image should have its own page and space. In addition, he wanted the pages large enough to give the viewer a feeling of experiencing the image as in a museum or exhibition. It was a bold concept and it won wide acceptance—garnering many awards and thrusting Brower and the Sierra Club into the national spotlight. Photographers, of course, loved it. In all, more than twenty Exhibit Format books were published during the decade.

In 1972, under the Environmental Protection Agency, another visionary program was initiated to document and serve as a benchmark of the state of the American environment. The first head of the EPA, William Ruckelshaus, recognized the value of photography in capturing the essence of environmental issues of the time. He wrote, “We are working toward a new environmental ethic in this decade which will bring profound change in how we live, and in how we provide for future generations. It is important that we document that change so future generations will understand our successes and our failures.” Called DOCUMERICA, the project was modeled after the FSA program, and its chief advisor was the famed FSA photographer Arthur Rothstein.

I was selected as one of the fifty photographers to participate in the program. Our task over the next few years was to document the state of the environment in America—the good, the bad, and the ugly. Some DOCUMERICA photographers lived in heavily populated and industrialized regions of the country. Many of them recorded serious air and water pollution problems of the time. Some, like me, lived in a relatively unspoiled region (I had moved to Colorado at this time). We all had our choices of what to photograph. At first, I chose to portray some of the beauty of the Rocky Mountain West. However, as time went by and as I traveled throughout the region, I became aware that places here were experiencing more and more destructive impact from mining, logging, dam building, and industrialization. It then became important for me to document the bad and the ugly.

Having spent so much time as a nature photographer capturing beauty, I found it difficult, at first, to show some of the damaging things being done in the region. What I had to learn was documentary photography—the art of dispassionately and accurately capturing significant events and subjects and everyday life, especially as they related to the environment. I spent a good deal of time studying the work of W. Eugene Smith, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Gordon Parks, Grey Villet, and other greats in the field. And, of course, I studied the FSA photographers to gain insight into this specialty.

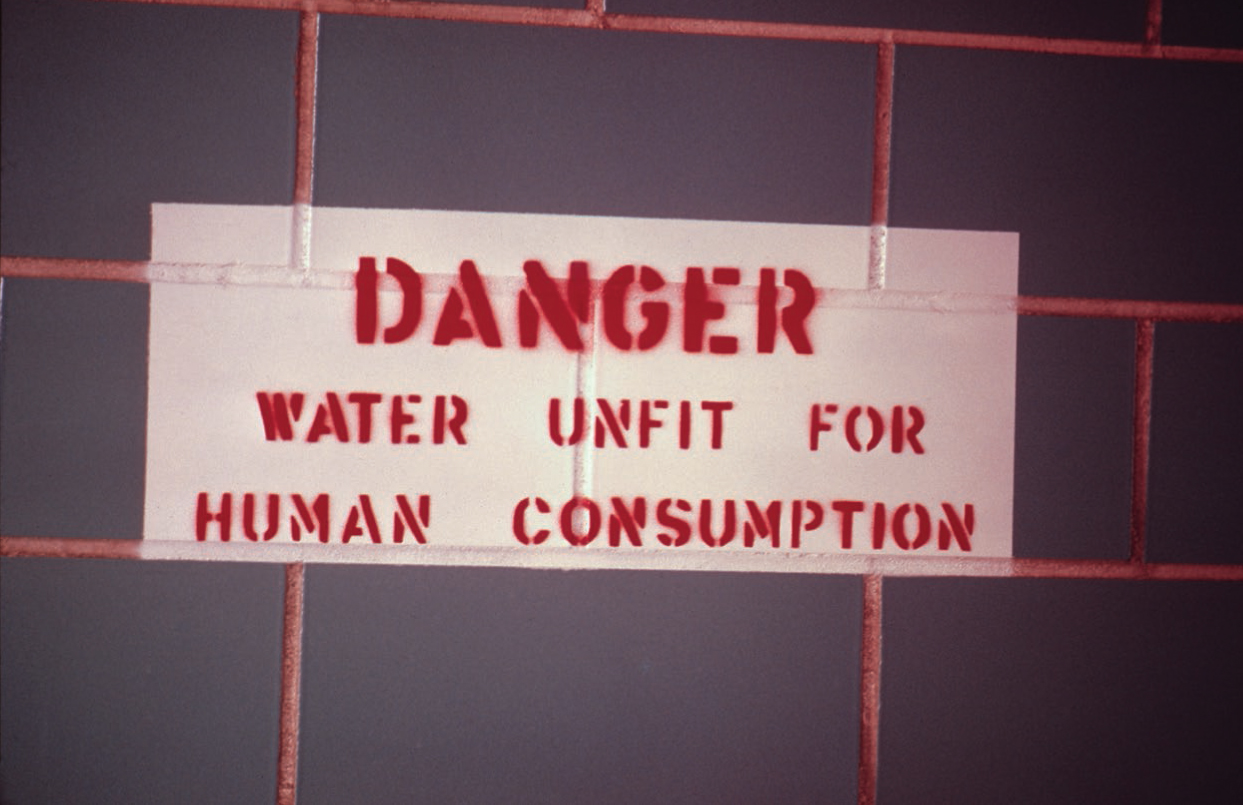

One of my early photos in the DOCUMERICA years was taken in a restroom in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Did photos like this provide incentive for passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972?

In this DOCUMERICA photo, I was struck by the subtle visual message of two forms of energy in the same ranch in Wyoming—one old, one relatively new. Even then, there were serious proposals for utilizing wind energy.

Because Project DOCUMERICA was a government-funded program, all photographs were in public domain and could be used freely by magazines, newspapers, and other entities. As the files grew in size, many of the photos were used to portray growing concerns over environmental degradation. One of my DOCUMERICA photos was published in Time, an aerial photo of a Montana strip mine illustrating the devastation caused by such mines.

Widespread publicity of environmental degradation through DOCUMERICA led to its demise by 1977. Industrial polluters applied lobbying pressure to halt the funding for the program. Today, tens of thousands of DOCUMERICA photos reside in the National Archives (www.archives.org). As a personal assignment, I urge you to peruse the collection and revisit some of the places documented. Your photographs of the conditions today can serve as an important reminder of problems solved or unsolved. The need for continued work is summed up well on the website:

When we look at images of today’s environment, we can see that what troubles the environment in the new millennium is what troubled it in the early 1970s, and DOCUMERICA confirms it. Thousands of images of pollution, strip mining, crowded cities, and land abuse could well be photographs taken in recent times. Though a great deal has been done over the past 30 years to correct problems depicted in the photographs, there is a common consensus that there is so much left to accomplish in the race to save America’s natural resources. The color images from the 1970s show us that Americans must keep lenses sharply focused until environmental solutions are realized. Project DOCUMERICA images serve to inform and inspire Americans as we pursue the green revolution of the new millennium.

Obviously, this was written a while ago—it is now well over 40 years since many of the photos were made. Go forth and continue the documentation. It is still vital and relevant if we are to make changes.