“It matters little how much equipment we use; it matters much that we be masters of all we do use.” —Sam Abell, National Geographic photographer

What do you need to become a conservation photographer? Not much, it turns out. Your cell phone will do. Or a point-and-shoot camera. The main objective is to create images of and about your environment that have significant impact and tell a story. It might be a case of recording a pollution problem—a stream, river, or lake where toxic pollutants are being dumped. Perhaps there’s a beautiful park or open space near you that you wish to record and share with others.

Smartphones. Sometimes simpler is better. We all carry smartphones nowadays, and some of the built-in cameras have multi-megapixel sensors that are capable of recording images and video of good quality. The advantage? The smartphone is light and portable and always within reach—whereas we may not always carry around a bulky digital single-lens-reflex camera (DSLR). Almost every night on the evening news we now see photos and videos taken with smartphones.

Point and Shoot. The next step up is a point-and-shoot (P&S) camera. These range from simple cameras that are often smaller than your smartphone to sophisticated models that look like scaled-down DSLRs. The latter are less likely to fit in a pocket or purse and therefore less likely to be carried wherever you go. The advantages of P&S cameras over smartphones are that many have zoom lenses with a much wider range and higher-resolution sensors. Depending on how you plan to use the pictures, the higher resolution and greater optical versatility can be important. Moreover, some models are water- and weatherproof, so they will serve well under conditions to which you would not want to expose your DSLR. Some P&S cameras can even be used underwater.

There are some drawbacks to using smartphones and P&S cameras. Most record images only in the compressed JPEG format, which may reduce their ability to be blown up as very large prints or cropped tightly for better composition or subject emphasis. JPEGs also suffer from a loss of quality each time the file is opened and re-saved. On the flip side, however, JPEG images are instantly usable on websites and transmitted electronically without any time-consuming processing. For better results, look for a P&S model that will capture in RAW format, which is much better for high-quality work—or a model that saves the files in TIFF format, which does not lose quality when the file is opened and re-saved.

This photo was made in the early 1970s for the EPA project DOCUMERICA. Citizens of Alexandria, VA, were warned to avoid all contact with the polluted Potomac River, a serious health hazard at the time. The photographer, Erik Calonius, used a professional single lens reflex camera. Today, this photo could easily be made using a smartphone. Public domain photo.

Even if you use a DSLR for most of your photography, P&S cameras have many advantages. They are small enough to be with you at all times. Many have excellent lenses and sensors—and some models are water- and weatherproof.

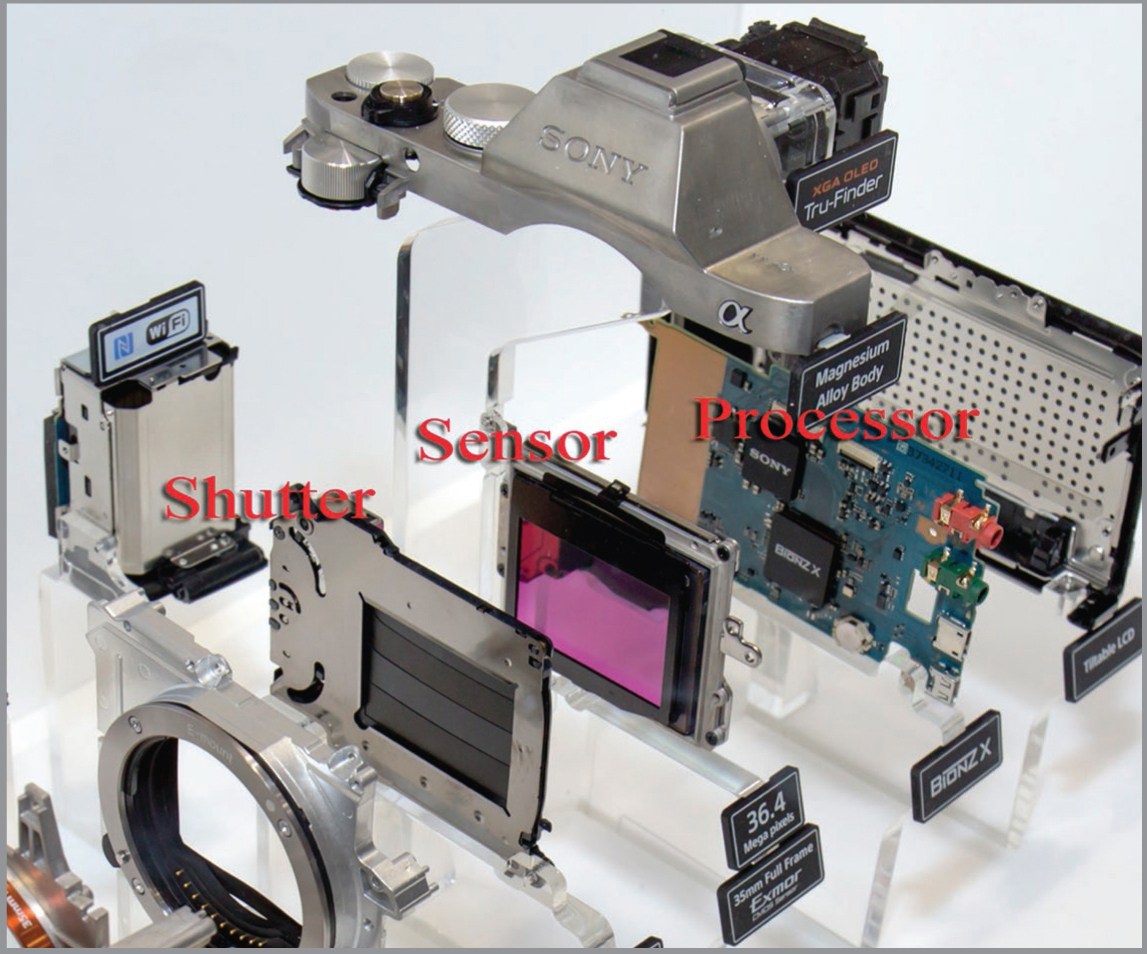

Exploded view of the Sony Alpha 7r 36-megapixel camera showing the full-frame sensor in relation to the shutter and processor. Photo credit: Morio.

This illustrates the 1.6x crop factor for an APS-C sized sensor, as used in some of my Canon DSLRs. The red area denotes the equivalent crop of the scene taken from the same place with the same lens. In other words, a 100mm lens will appear to be equivalent to a 160mm lens on certain Canon cameras with an APS-C sized sensor. The Nikon DX format is somewhat less of a crop at 1.5x.

An additional drawback to using smartphones and P&S cameras is the tendency to take snapshots rather than a more studied approach to the scene or subject. That can be overcome by taking more time and care, but using a DSLR does tend to make for a more careful and methodical approach.

DSLRs. The two primary advantages to DSLRs are higher-resolution sensors and the flexibility of high-quality interchangeable lenses. The disadvantage is the weight and bulk of all the equipment, though this should not be much of a deterrent as you get more serious about your work or embark on a long-range project. (As a side note, current high-end mirrorless cameras offer many of the same advantages as DSLRs and are much lighter.)

For highest-quality documentary work in conservation, a DSLR is vital. Most, if not all, DSLRs can give you the option of storing the images in RAW format, which stores more of the digital information recorded by the sensor, thus allowing you to create final images with greater detail, color, and tonal range. Most DSLRs also allow you to shoot and store a JPEG image simultaneously along with the RAW file, should you have need for an instantly usable image. I do not use this approach because it reduces the number of RAW images I can store on a memory card. If I need a JPEG, I create one in Lightroom on my laptop. Virtually all DSLRs also allow you to shoot HD video—and some allow shooting 4K HD video for even higher quality. More about this in chapter 14.

Sensor Types. Don’t be confused by the alphabet soup of CCD (charge coupled device) and CMOS (complementary metal oxide semiconductor). They each transform light into electrons that are gathered and stored as digital data that is then processed to create an image file. Which is better? In my opinion it doesn’t matter; there is little difference between the two from the standpoint of final image quality. Both types have been improved over the years and the improvements will continue.

Sensor Sizes. A more important consideration is sensor size. Yes, size does matter—although, as I’ll point out in a moment, smaller can be beneficial.

First, there are cameras with “full frame” sensors. This means that the sensor is the same size as a frame of 35mm film (24×36mm or 0.945×1.42 inches). Then, there are cameras with APS-C (or, in Nikon terminology, DX) sensors that are about ⅔ the size of a full frame. From the standpoint of quality images, is there a difference? Yes, but not as much as you might think.

If you have need for making really large prints—greater than 16×20 inches—then a full-frame camera of 20MP or greater will help you achieve the best quality. This will be especially true if you do much cropping. If your needs are more modest in terms of print size, or if you print pretty much without cropping, then a smaller APS sized sensor will be suitable and can yield excellent-quality images for publication and presentations. Bear in mind that, with a few exceptions, full-frame camera bodies tend to be larger and heavier. The exceptions are mirrorless cameras, such as the Sony A7 series, which are not only full frame but also surprisingly light and small.

The Sony A7r delivers a 36MP image. As of this writing, Canon has announced their new Canon 5DS and 5DSR 50MP cameras. Nikon also has a 36MP model D810. For most publication and print usage, these large megapixel cameras may seem to be overkill. Does anyone need a 36MP or 50MP camera for conservation photography? I never thought so until I used the Sony Alpha 7r on a recent trip to Serengeti National Park, where I have been documenting parts of the ecosystem for more than 30 years.

This young Thomson’s gazelle in Serengeti National Park is being tended to by the mother. Even with a 200mm telephoto lens on the Sony Alpha 7r, I could not approach too closely for fear of frightening them off (top). But the amazing resolution of this sensor allowed me to crop in tightly for a more detailed look at Mama licking her youngster (bottom).

Since these large images can be cropped or zoomed in to reveal more detail within small areas of the image frame, they allow you to produce long-range documentations that are very useful for tracking changes in, say, vegetation or melting glaciers over time. This capability was never possible with film, with which you had to use longer focal lengths to isolate different parts of a larger scene (or move in closer to these parts with smaller focal lengths). Wildlife researchers can also benefit by using these high-resolution cameras to document the health of certain species without invading their space.

There was a time when fixed focal length lenses optically outperformed zoom lenses. That’s no longer true; zoom lenses today are so good that there is no reason not to use them. By careful choice, you can reduce the amount of equipment you carry in the field.

If you use a camera with an APS sized sensor there is a crop factor that you need to be aware of. Two of my camera bodies have a 1.6x crop factor, meaning that a 100mm focal length creates an image equivalent to a 160mm lens on a full-frame sensor. That crop factor is nice when using telephotos or telephoto zoom lenses for wildlife. My 100–400mm zoom lens becomes the equivalent of a 160–640mm full-frame lens.

However, that crop factor is a disadvantage when using wide or ultra-wide lenses. For example, if you use your favorite 20mm ultra-wide angle lens on an APS sensor camera, the crop factor of 1.6x will make it the equivalent of a 32mm lens—not so ultra-wide. To overcome this drawback, many manufacturers have special wide angle lenses designed for APS sensors. (These special lenses cannot be used on full-frame cameras as vignetting results.) For my system, I have a special 10–22mm zoom that gives me the equivalent (with crop factor) of a 16–35mm lens full frame. The 16mm focal length is nice for achieving certain ultra-wide effects (more about that later).

With elephant poaching reaching crisis proportions across Africa, maintaining the health of existing populations is important. Keeping a good distance (top) and using a 70-200mm zoom with the Sony Alpha 7r allowed for cropping (bottom) to examine the baby without disturbance.

In a later chapter, I’ll discuss the important uses of various lens focal lengths for achieving impact. For now, I’ll point out that my basic outfit consists of two DSLR camera bodies (both with APS-C sensors) and three lenses: a 10–22mm zoom, a 24–105mm zoom, and a 100–400mm zoom. As you can see, this gives me an enormous range of focal length, and I use all three lenses often.

The GoPro is a tiny gem capable of capturing video and still photos of excellent quality.

Having precise GPS coordinates can be extremely valuable in conservation photography. As seen here, external units (for those cameras without built-in GPS) can be mounted to the flash hotshoe.

Even though I don’t jump out of perfectly good airplanes, I carry a GoPro. It is a high-quality camera giving 12MP still photos and 1080p HD video. It is my all-weather and underwater camera of choice. For traveling light, it can’t be beat. A GoPro app available for iOS, Android, and Windows smartphones also provides a live view via WiFi and allows for full remote operation of the camera.

For a large amount of documentary and conservation photography, I consider a GPS–capable camera vital. From DSLRs and P&S to smartphones, many cameras have built-in GPS units that record your coordinates directly into the metadata for each image. This information can be of immense importance later. This location data becomes vital if you want to record changes to landscapes or vegetation or river channel flows or glaciers melting over long periods of time.

If GPS isn’t built into your DSLR, most major camera manufacturers have add-on units. I have one such unit for one of my Canon camera bodies. The only drawback is that it plugs into the hot shoe atop the camera, making it a bit vulnerable to being knocked or broken off. Absent such a unit, you can shoot with your DSLR, then take a quick shot on a GPS-enabled smartphone or P&S to record the locale. That GPS data can later be added to the DSLR’s image metadata in Lightroom or Photoshop.

The main objective here is to use your equipment effectively to create images with impact. Even your smartphone should be considered a part of your arsenal because you may not always be traveling with all your sophisticated equipment. For times when you need to work quickly, a P&S camera may be the best choice. Sometimes, the size and bulk of a DSLR and big lenses may attract attention when you don’t need it. In other words, keep it simple and effective when possible.

Even the simplest P&S cameras have evolved into sophisticated image recorders, with many outstanding features. And on today’s DSLRs, there are a bewildering number of features. I often joke in my lectures and workshops that I used to run nuclear reactors that were less complicated than my DSLR. But, seriously, all these features are designed to give us a great array of creative options. Familiarize yourself with many (if not most) of the features and learn how to use them. This is especially important when you are working in the field and need, for example, to switch your camera quickly from single shot mode to continuous shooting to capture rapidly changing action.