8. Picture Dynamics: Creating the Strongest Images

“There are no rules for good photographs, there are only good photographs.” —Ansel Adams

Clutter and chaos are the attributes of this photo. There are possibilities in this scene to create something stronger, with more impact.

Our cone of concentration zeros in on a part of the scene that is more unified and aesthetically pleasing.

By moving in closer (or zooming in optically), we can isolate that pleasing part and eliminate the chaotic elements.

I have often envied painters. They can start with a blank canvas and add only those elements needed to create a dynamic image—one that can grab your attention. True, not all paintings do grab your attention (and some are just downright boring), but the freedom of expression is still there for the artist. Photographers, on the other hand, are more limited and must work with the real world, one that contains much visual chaos. And although we can eliminate much of it, not all photographs are dynamic and exciting. Why is that?

Composition is the arrangement of visual elements to create the strongest images. My three important tips for creating the dynamic composition are exploration, isolation, and organization.

Exploration. Explore the aspects of scene or subject before firing away. Is the lighting right? Is there too much contrast? Would softer lighting be better? What about the angle of view—should you choose a high angle or a low angle? What perspective works? Would telephoto lens compression make the background more dramatic or would using a wide angle lens and great depth of field expand the perspective?

It’s true that sometimes we have to work quickly—the light is changing rapidly or the wildlife is moving away. But when time allows, give some thought as to how best to capture that scene or subject. As you gain experience you can often work quickly for the best rendition under changing conditions.

Note the off-center, dynamic placement of the two wildebeests fighting. In addition, the diagonal slope of their backs gives a strong sense of action. The low, off-center placement of the horizon line conveys the spaciousness of the Serengeti Plains. Finally, backlighting and silhouetting the animals made for a more dramatic picture.

Isolation. Get rid of extraneous elements that clutter the composition. Move closer (unless the subject is a grizzly bear or lion) or isolate optically by zooming in. Tighten it up. The most important part of this process is defining your subject or center of interest. At times, that may be difficult.

We might call this the psychology of seeing. Our eyes are constantly moving, looking at various parts of a scene in front of us. Even while looking straight ahead, we are aware of objects in our peripheral vision. But while we may have great peripheral vision, we also have a psychological cone of concentration. We mentally zero in on something that catches our fancy—one leaf in the midst of many others, or a small stream in the clutter of a forest.

Organization. This is what we think of as composition. Where do you place the center of interest? More fundamentally, what is the center of interest? Where do you place a horizon line—centered, high, or low in the picture? What is the impact of such placement?

The term “composition” refers to the arrangement of elements in a picture. I prefer the term “picture dynamics” because creating a strong photograph is a dynamic process. We need to think about how we arrange the various elements in a picture and how those elements interact. As I said above, the painter has almost unlimited freedom to add or subtract visual elements from their picture. For photographers, the process is tougher; we have to deal with the chaos in front of our lenses and decide how to eliminate the more distracting elements and zero in on the important ones.

Let’s consider the various visual elements that comprise any work of art, be it a drawing, a painting, or a photograph. These elements are lines, shapes, forms, textures, patterns, colors, and perspective (or depth). (This last one, perspective, was covered in chapter 5.

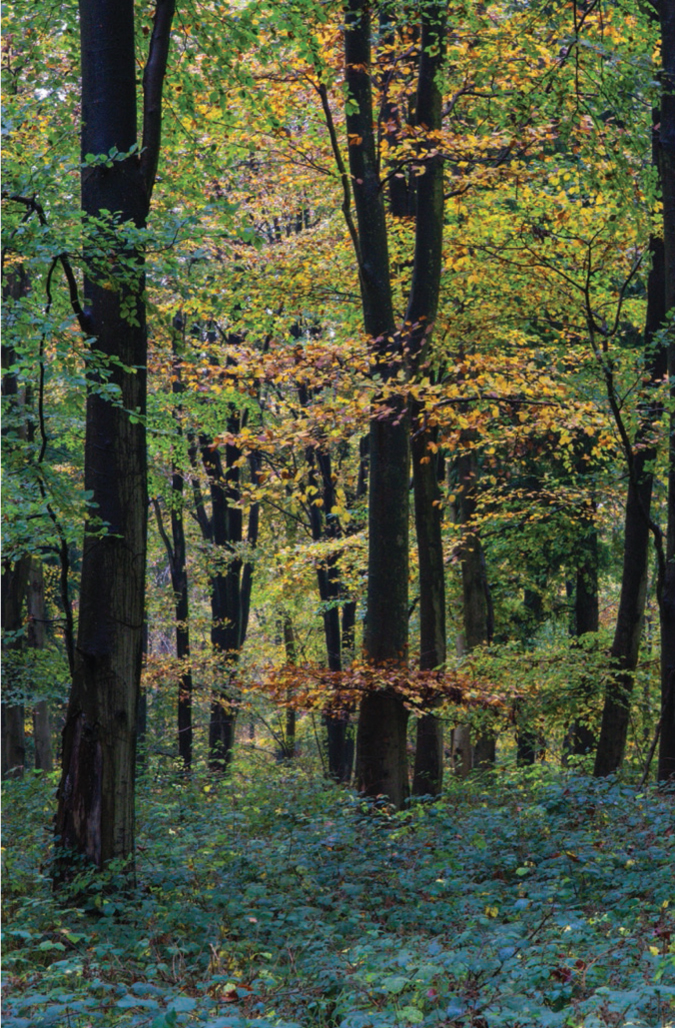

Shooting as a horizontal gives a repeating pattern of vertical lines in this English forest.

However, shooting as a vertical give strong emphasis to the tallness of the trees. Both pictures document a pleasant piece of nature.

Lines. Lines are everywhere in our world—straight lines, curved lines, and implied lines (a series of objects aligned in certain ways have the properties of real lines). Vertical lines tend to create a sense of height, or perhaps grandeur. A forest of trees with strong vertical lines does enhance that feeling.

Horizontal lines impart a sense of stability, tranquility, and earthiness. Horizon lines generally have these attributes, as seen in the wildebeest image to the right. That horizontal line feels solid and earthy and certainly stable, with all those animals trampling on it. Note that the placement of the horizon line low in the photo gives a sense of openness and spaciousness, which is exactly the feeling you would expect in the Serengeti Plains. Even though water does not have the solidity of land beneath our feet, there is a sense of tranquility in the photo of a schooner at sea (bottom right). The strong horizontal line conveys just that sense.

In contrast to the solid feeling of horizontal and vertical lines, diagonal lines feel unstable and dynamic. If you want to convey action, emphasize the diagonal lines in the photo. My fighting wildebeests (facing page) illustrate that point with the diagonal slant of their backs, legs, and tails. And look at the dynamics of this photo (top left) of trees in the Falkland Islands. You can almost feel the howling wind that has tilted these trees into a permanent lean.

Placing the horizon line low in the picture creates a strong sense of spaciousness and vastness, just what you would expect in Serengeti National Park with its wildebeests.

Again, the low horizon line emphasizes the vastness of the sea in this shot of a schooner in the Caribbean.

It’s not hard to tell the direction of prevailing winds here in the Falkland Islands. Those diagonal lines create a dynamic feeling of howling wind.

There’s obviously some adrenaline pumping action among these waves in Wild Sheep Rapid on the Snake River in Hells Canyon, but it is diminished somewhat by the placement of the raft in the center of the picture.

Placing the raft off center and catching it in a more diagonal position creates more dynamic action visually.

For a sense of action or movement, look for the timing and position of your subject(s). In the two photographs (left), we see rafters running one of the rapids on the Snake River in Hells Canyon. Notice how the diagonal position of the raft in the second picture conveys a stronger sense of action and movement. In addition, the raft in the first picture is very close to the center of the picture, a static arrangement. In the second, the raft is composed off-center, a more dynamic arrangement that enhances the feeling of action.

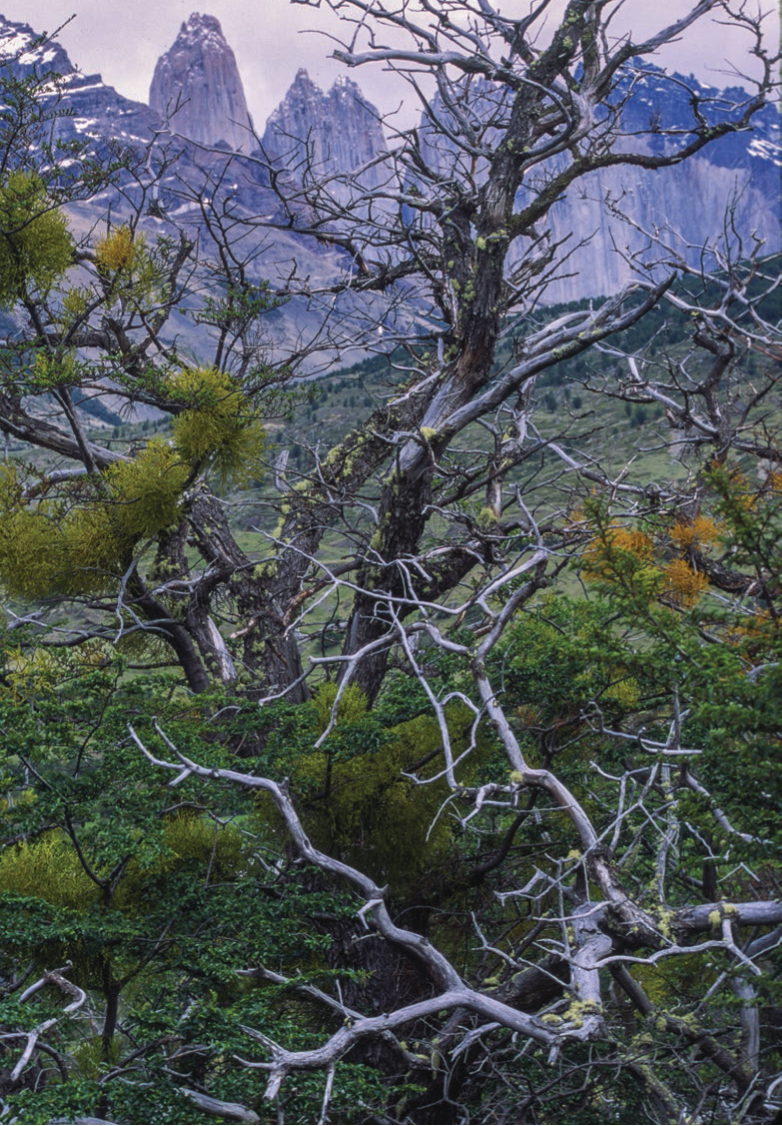

Intersecting or zig-zagging lines can be chaotic and create tension—perhaps even a feeling of uneasiness. In Chilean Patagonia, I photographed these bare jagged branches (facing page, top) because this forest did not have that peaceful or restful feeling of other forests I’ve visited. I suppose the bare branches and the jaggedness of them is due to the infamous Patagonian winds that rake the land here.

These jagged lines create a feeling of tension, reinforced by the darkening sky of an approaching storm over the peaks of Torres del Paine in Patagonia, Chile.

The receding lines, enhanced by using a 20mm ultra-wide lens at ground level looking upward, give a feeling of tallness.

We can also use lines to enhance certain physical attributes of the scene or subject, like tallness or height. This photo (top right) of giant Sequoia trees was made with a 20mm ultra-wide lens pointed straight up from ground level. The convergence of the lines gives a strong sense of tallness.

The next photos (below) present a similar use of converging lines to create a sense of depth—again with the use of an ultra-wide lens placed close to the ground to emphasize those ripple patterns. Notice how the sense of depth is lessened in the horizontal version of this image.

Converging and receding lines add depth to this photo, shot with a 20mm ultra-wide lens very close to the ground. Choosing a vertical orientation emphasizes the effect because it limits side-to-side viewing and forces the viewer to look into the picture from the foreground to the background.

Notice how the sense of depth is lessened by choosing a horizontal orientation and allowing more side-to-side viewing.

Even though it’s very soft lighting, the subtle shading in the rocks gives them a feeling of roundness and form. This was on the wild Salmon River in the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness Area in Idaho.

The near-sunset light gave strong sidelighting to these dunes in Death Valley, enhancing the texture of the ripples and sand.

Low-angle sunlight brought out the texture of this dried mud next to the sand dunes in Death Valley.

Shapes and Forms. From childhood on we acquire a memory bank of recognizable shapes—circles, squares, and triangles, plus certain irregular shapes such as airplanes or birds in flight, trees, and more. Even when seeing them in silhouette we instantly know what they are. A painting or a photograph is a two-dimensional rendition of a scene or subject, made up of various interacting shapes. To give a sense of three dimensions, we must give form to those shapes. Light and shading is the way we do that. Sometimes it’s subtle, as in the top left picture.

Texture. Texture represents the tactile quality of surfaces. It can vary from smooth to rough, and oblique lighting is important to bring out these qualities. Texture can also add dimension to a picture. Note how the dried mud in the photo to the left gives a sense of three dimensions.

Color. Color is one of the strongest elements in picture dynamics because we react to color in very emotional ways. We can look at a photograph of a campfire and almost feel its warmth in the dancing red, orange, and yellow flames. At the other extreme, the subtle blue of a winter scene conveys coldness. Our vocabulary reflects the ways that certain colors affect us—“seeing red” as an indication of anger or having “the blues” to denote sadness. The impact of color can be subtle, but it can have strong impact on the success of a picture. Let’s look at the spectrum of color and see what psychological implications there may be in photographic compositions.

This photo was shot on film, later scanned. The slight blueness was not removed because I wanted this picture to convey the cold feeling.

Blue is often described as a receding color because distant scenes tend to have a blue haze.

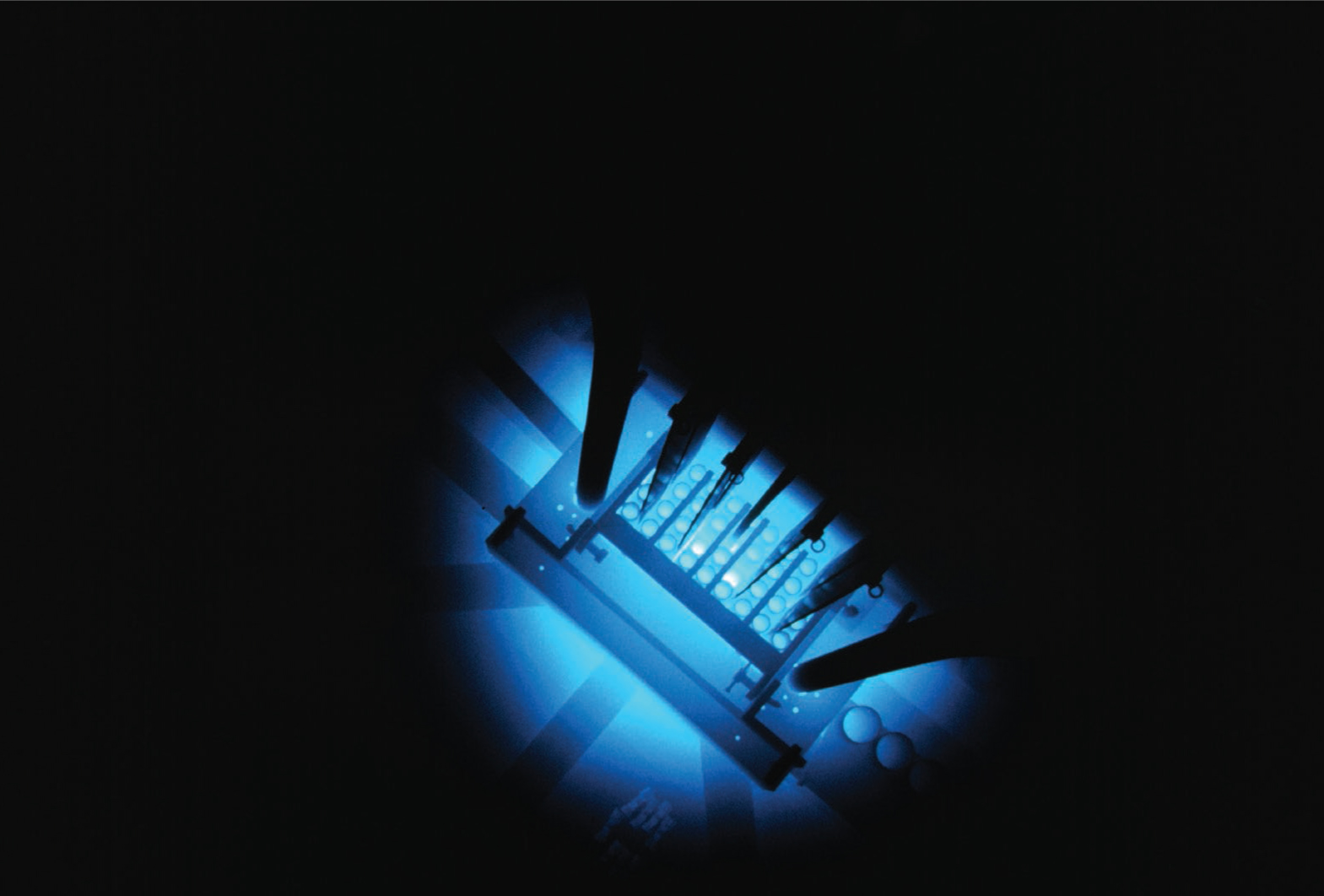

Blue may also be quiet—or quietly ominous, as in the glow of radiation in a nuclear reactor at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico.

As mentioned above, blue is associated with coolness or coldness, as in my images of icebergs floating beneath the face of an Antarctic glacier (top right). Blue is also the color of distant objects, and is thus often referred to as a receding color. To me, blue also seems a quiet color. Blue whispers; blue is tranquil. However, it may also convey something quietly ominous as in the photo I made of the glow of radiation in a nuclear reactor at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico (bottom right).

Green feels cool and conveys a sense of peacefulness, as in this English forest. The blue flowers also impart a small amount of coolness.

Green is quiet—as silent as the forest here in a Russian nature reserve in the Siberian Far East.

Yellow and red are lively colors, attracting attention when they predominate.

The vibrancy of yellow and orange make us associate those colors with autumn.

Red screams and attracts attention—and it could also be a warning if you bite into one of these chili peppers.

These Sally Lightfoot crabs in the Galapagos stand out boldly against the black lava rock.

Green is also a cool color, but less so than blue. Of course, we associate green with nature and it lends an air of quietness to a scene where it predominates—as in my image of an English forest (facing page, top left). Green is also silent, as seen in this lush forest in the Russian Far East (facing page, top right), habitat for the world’s last remaining wild Siberian tigers. Incidentally, this exact area is the place where two books (The Tiger by John Valliant and Tigers in the Snow by my old friend Peter Matthiessen) detailed the killing rampage of two Siberian tigers. If these books had been published before I visited this forest, I would have looked over my shoulder more often.

Yellow is a lively color, imparting warmth. There’s nothing subtle about yellow, especially a whole wall of it. This photo (facing page, center left) was made in the Barrio de la Boca district of Buenos Aires, Argentina. Including a red window made for a striking juxtaposition. Both yellow and orange make us think of autumn, like foliage turning and pumpkins at a farmer’s market.

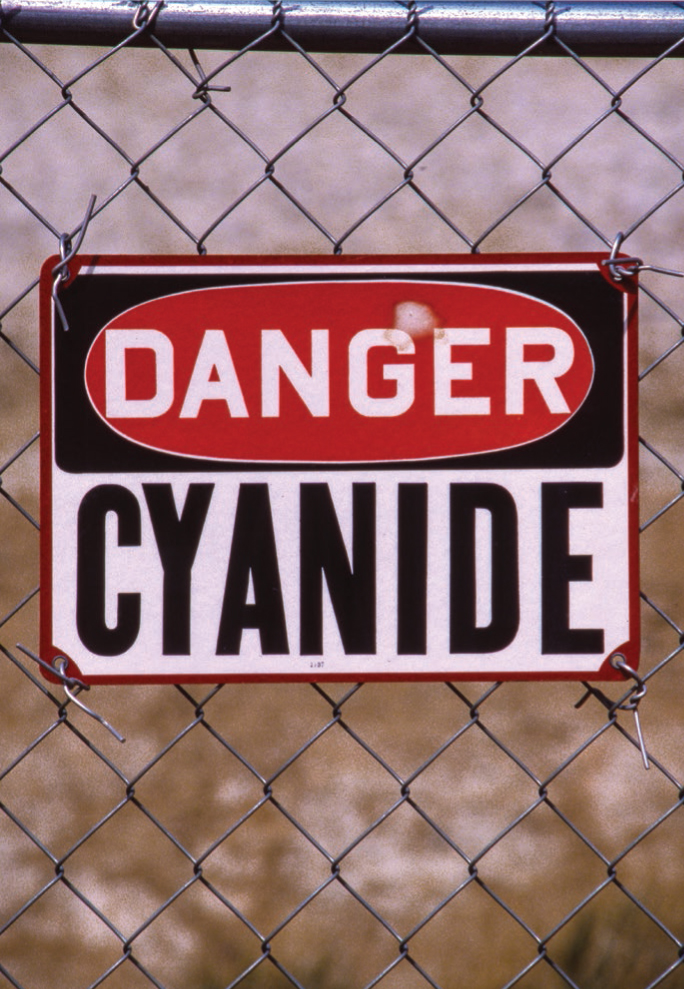

And then there’s red—hot stuff, literally, as in these hot chili peppers in an Ecuadorian market (facing page, bottom left). It’s also hard to miss Sally Lightfoot crabs on the black lava of the Galapagos Islands (facing page, bottom right). And, of course, red means danger. This sign (below) was on the fence surrounding a leaching pond in Colorado. The cyanide leaches gold out of tailing piles from old mines. Even though the pond was lined with heavy neoprene rubber, local citizens are concerned about this poison leaking into ground water.

Patterns. Patterns are useful in making us see things in a different way. The key to capturing a good pattern is in conveying some unity or rhythm. This is illustrated by a pattern I photographed on a fern in a Russian forest; I was looking straight down at it (top right). There is a rhythmic flow of lines and shapes and colors, all leading the eye to that leaf in the bottom center. As shown in the bottom right image, however, patterns may not be so pleasing. Fellow DOCUMERICA photographer Chuck O’Rear documented this rhythmic march of towers and power lines across the desert in the 1970s.

A successful pattern shot is one with pleasing, rhythmic flow of lines and shapes and colors.

A rhythmic pattern not so beautiful, power lines and towers stretching across the desert. This photo was made by a fellow DOCUMERICA photographer Charles O’Rear.

We associate red with danger, as in this sign on a leaching pond in Colorado. Local citizens are concerned about this deadly poison leaking into ground water.

Orientation makes a difference in terms of a photograph’s impact. Think of it this way: a horizontal shot is like looking out a picture window. You can see the sweep of a landscape from side to side and this helps convey a sense of openness and grandeur on a large scale. A vertical photograph is like looking out a narrow window. You look into the landscape, from the foreground to the background. This may make it important to have strong elements in the foreground because you are looking directly into them.

Using a 20mm ultra-wide lens close to the ground I photographed the pitiful attempt of a mining company to reclaim the land that had been strip mined. I wanted to emphasize the sparse blades of non-native grass. I shot this in midday, with direct overhead lighting to emphasize the starkness.

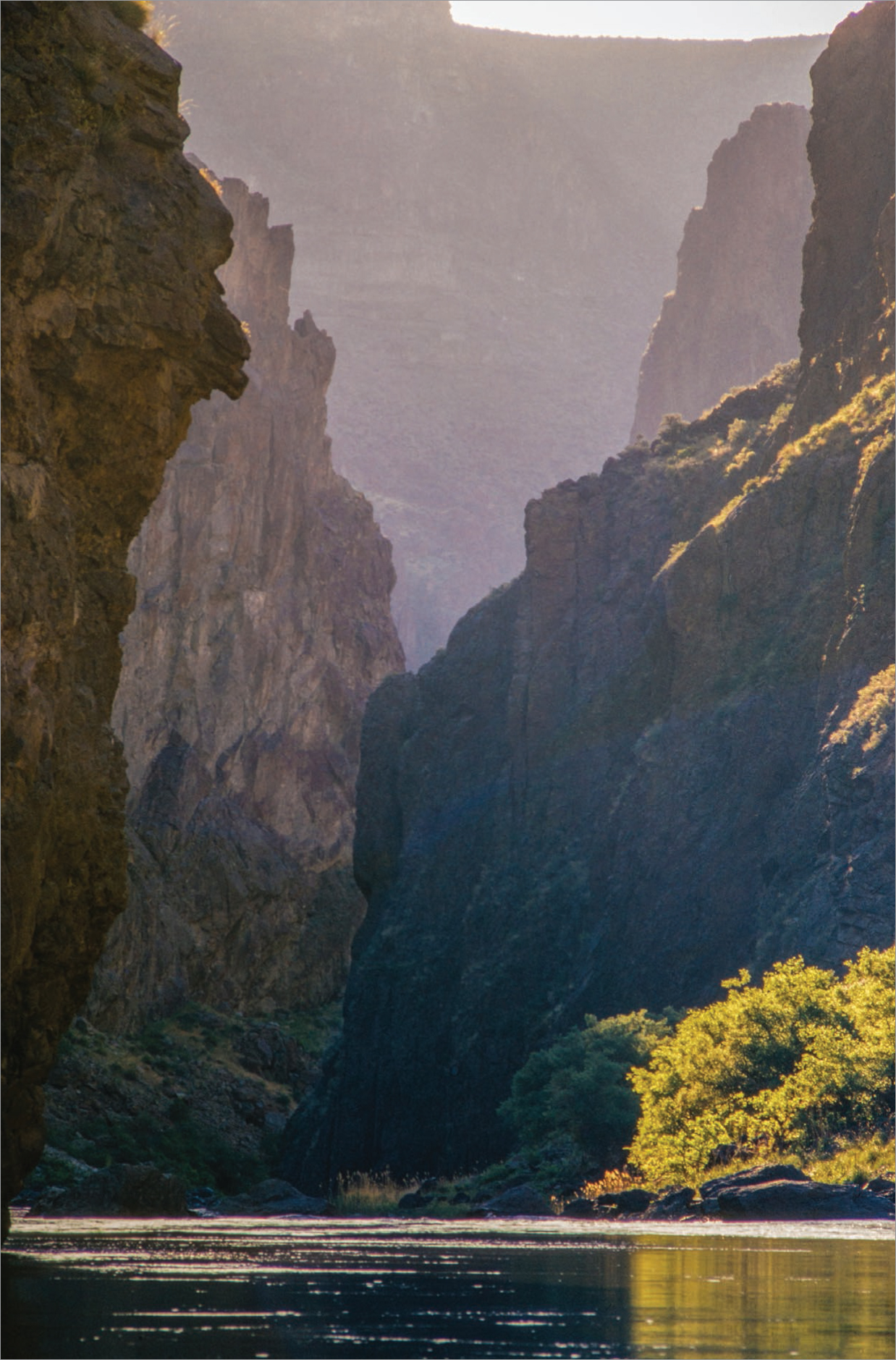

On a whitewater raft trip in the remote Owyhee River in southwest Idaho I made two photos of this spectacular gorge from nearly the same place. The horizontal presentation does not convey the depth and steepness of this gorge as well as the vertical one.

In addition, horizontal and vertical orientations have a different sense of scale. For example, if you wish to convey the height or depth of a canyon, the vertical shot can emphasize that. Horizontal photos give more space to allow the eye to sweep side to side, making them well suited to subjects like broad landscapes.

How does knowledge of all these compositional elements help you to portray issues around saving places? Often, the contrast between the spoiled and the unspoiled helps reinforce the need to protect wild lands.

In chapter 6, I showed a photo of two Montana ranchers fighting to save their land from strip mining. I asked the coal company’s office for permission to photograph what they said was reclaimed land (above)—that is, after the mining had taken place, the huge open pits were filled in with overburden that had been removed to get at the coal. Grass was planted on this reclamation plot and watered, almost constantly. The company’s public relations person proudly showed me this “reclaimed” area, pointing out that it might take a few years for the land to return to normal. (I learned later that this land had been mined 20 years earlier and it still looked ugly.) After seeing this image, the obvious question comes to mind: Will this place ever return to productive ranch or farm land?

I placed the horizon low in the image to give a sense of openness of the prairie and farmlands. Montana is called “Big Sky Country,” after all. Photos like this add to the story in a strong way.

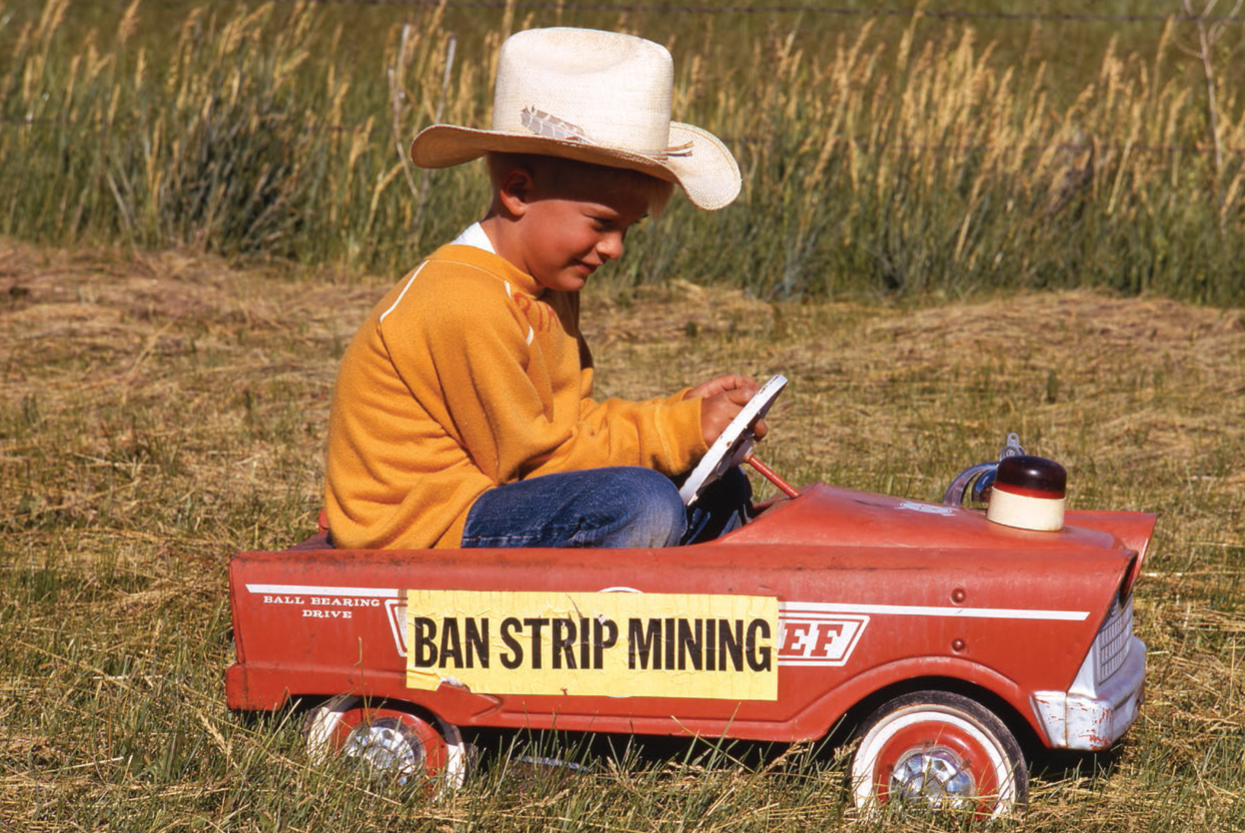

A youngster on one of the ranches plays with his toy car with a bumper sticker expressing feelings about the mining. Part of the story.

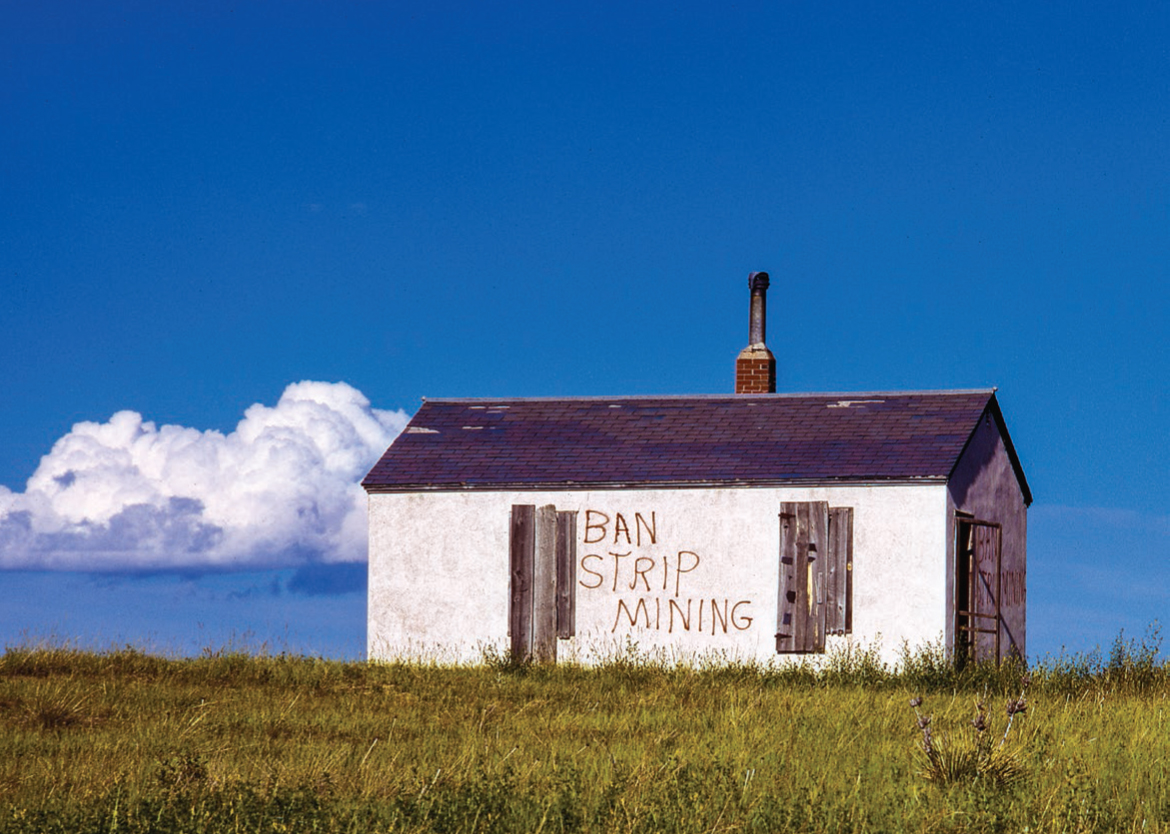

Feelings ran high in this region. Due to a quirk in Montana law, those ranchers did not own the mineral rights beneath their lands. Some ranches had been in families for generations. To portray the feelings, I photographed some graffiti on one of the ranches, as well as the bumper sticker emblazoned on a toy car owned by one of the ranchers’ sons.

Finally, I photographed a coal-fired power plant in Wyoming. I wasn’t satisfied with the first angle and lighting for the photo (see captions below). It seemed too neat and tidy. So I waited until later in the day, near sundown, and made my second shot from the opposite side of the plant. I deliberately made it look more cluttered by including the poles and power lines.

This plant in Wyoming was not far from the area where the ranchers were threatened with loss of their land to coal mining. However, this image didn’t quite have the right quality to help tell the story.

Late afternoon backlighting made the power plant appear more ominous in silhouette. I positioned myself to include the clutter and visual chaos of power lines and poles.