“The quicker we humans learn that saving open space and wildlife is critical to our welfare and quality of life, maybe we’ll start thinking of doing something about it.” —Jim Fowler

For a conservation photographer, perhaps one of the most important factors in photographing wildlife is relating animals to habitat. This is important if you are involved in protecting a particular ecosystem threatened with destruction. Resident wildlife there is dependent on that ecosystem. It becomes a challenge, then, to portray this relationship in a meaningful way. A series of photos might do it: close shots of various animals, habitat photos of the region. A single photo, done well, can have significant impact.

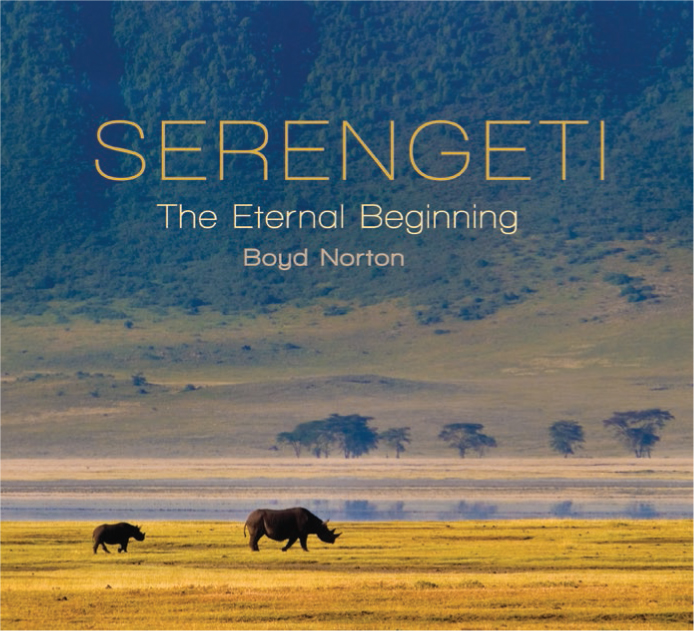

Why did we choose this picture for the cover of my book? Rhinos are near extinction in the wild. This photo imparts a sense of solitude against a vast landscape. It asks, “Are these the last two rhinos left on earth?”

We are always attracted to what might be called the charismatic megafauna, the large animals in a particular habitat: moose, elk, deer, grizzly bears, bighorn sheep, elephants, lions, etc. These are important, but don’t overlook the small critters. In many ways, these are more challenging but equally significant.

A good example is the pika, a small rabbit-like mammal living above timberline in the high mountain country of the West. Pikas have been likened to canaries in a coal mine, warning us of the dangers of global warming. How? Pikas are adapted to very cold temperatures. Rather than spend a winter in hibernation, they harvest and store tundra grasses in rock shelters under deep snow and pass away the frigid season wide awake, happily feeding. Warming temperature, diminishing snowfall, and fewer grasses in the high mountains are forcing pikas to even higher elevations. But when they’ve reached the tops of the peaks, there isn’t anywhere else to go. This is but one conservation story to be told.

The large species (here, a moose and calf in Alaska’s Kenai National Wildlife refuge) are always fun to portray—but don’t forget the smaller critters. All of them, large and small, have niches in the ecosystem.

The American pika is a small lagomorph (rabbit family) that lives in cold, high-elevation habitats. The species has been likened to the canary in a coal mine, in this case being adversely affected by global warming. Pikas have disappeared from more than a third of their previously known habitat in Nevada and Oregon. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is considering classifying them as an endangered species. This one was photographed near the 14,000 foot summit of Mt. Evans in Colorado.

Elk in the road in front of my home in Colorado’s Front Range. This is indicative of certain species adapted to humans in their environment. Elk are so common that no one pays much attention to them—until they eat the flowers or vegetables in your garden.

Undisturbed landscapes have at least two attributes important to most people: beauty and wildlife. There are other things of importance as well (such as watershed protection, recreation value, and air quality), but for many people unspoiled nature is wild animals and scenic splendor. Polls have shown that wildlife viewing is one of the top aims for national park visitors.

As a photographer, you’ll probably find it easier to document the aesthetic features of the place. Wildlife takes a little more time and patience. If the area you are documenting is near your home, you are probably familiar with the wildlife there. If it’s a place in a distant region, then research is important. A simple online search can bring up a wealth of information. In fact, you may be surprised to learn about threatened species even in the habitat you are familiar with.

To test this, I entered in Google Search “wildlife in front range of Colorado.” Now I’ve lived in Colorado’s Front Range for nearly fifty years and I’m familiar with much of the wildlife because I often see mule deer, elk, and foxes right outside my office window. Neighbors have seen mountain lions, bobcats, black bears, and even a wayward moose. Not far from home, on Mt. Evans, I have photographed mountain goats, bighorn sheep, and smaller species such as marmots and pikas. But I had never heard of a Preble’s meadow jumping mouse.

“Undisturbed landscapes have at least two attributes important to most people: beauty and wildlife.”

It happens that this species is listed as threatened on the Endangered Species list and is found only in Front Range habitat in Colorado and southern Wyoming. It may also be an indicator species reflecting the water quality in the region because its preferred habitat is alongside pure, healthy streams lined with grasses it uses for food and cover. So, you see, research can bring a lot of information to your attention and give you ammunition in your battle.

Both universities and government agencies often have research data on various species. Spend time online looking at research projects. What species are protected? Do they need protecting? Are they in the process of being protected? Does anyone know about them? As you answer these questions, you’ll learn which research groups are working with your subject matter. Not only can they help you get the inside action on an issue, but they can be an outlet for some of your photos over time. It is not unusual for conservation photographers to become citizen scientists.

Behavior is important as it relates to habitat. Some animals need lots of space. Perhaps the best example is the migration of wildebeest, zebras, and other herbivores in the Serengeti and other ecosystems in Africa. Food and water are the driving force behind this migration. This creates the behavior pattern for moving on.

Many people are not aware of it, but we also have significant wildlife migrations here in North America. These migrations include deer, elk, bison, and hibernating snakes (including rattlesnakes in the Northeast). But perhaps the least known has been the migration of pronghorn “antelope” (they are not a true antelope but a distinct species). Having been hunted for centuries, they are notoriously shy animals, and documentation of their movements has been very difficult. However, recent technical developments have enabled photo documentation through the use of camera “traps”—remote, self-triggered cameras.

Massive herds of wildebeest and zebras migrate across the Serengeti in a never-ending search for water and fresh grasses. Anything that blocks the migration has enormous impact on the whole food chain.

This lone lioness, looking for her next meal across an empty landscape, symbolizes the plight of predators at the top of the food chain should the migratory herbivores disappear. The loss of keystone species can unravel a whole ecosystem.

Joe Riis has become an expert on placing camera “traps” to capture shy wildlife. His documentation of the pronghorn migration from Jackson Hole, WY, to the upper Green River wintering ground has been featured in National Geographic and other major magazines. Photo credit: Joe Riis.

Joe Riis also documents the perils facing pronghorn migration: crossing a highway used by big trucks associated with the massive oil drilling activity in the region. Photo credit: Joe Riis.

One of the best-known experts in using this technology is Joe Riis. Joe was trained as a wildlife biologist. He is now a full-time photographer and an associate Fellow of the International League of Conservation Photographers. “I’m a South Dakotan, a lover of wild places, and an adventurer in search of wildlife stories that inspire people to leave room for wildlife to roam,” says Joe. “I strive to blend science and field biology with photography and environmental conservation.”

When Joe began his pronghorn project, he recognized the difficulty involved. “Because of predators and hunting you can’t get close to them. I’m not a gear guy, but I realized that camera traps were the only way to document their movements.”

Knowing where to place a remote camera is tricky. Joe Riis’ background as a wildlife biologist helped, as did working with other researchers studying the pronghorn migration. These animals are so shy that it would be impossible to get this photograph if you were sitting there with a camera. The pronghorn would be long gone. Photo credit: Joe Riis.

A commercial camera “trap” in a weatherproof housing, capable of recording VGA digital video and 8MP still images in bursts up to 6 photos. Its infrared LED illuminates up to 50 feet.

The pronghorn migrate in the fall from Jackson Hole to the Green River Basin wintering ground, covering about 120 miles. During the move, they must negotiate fences (they don’t jump but have to crawl under them, if possible), a major highway, oil drilling rigs, and a swim across the Green River. In the spring, they reverse the migration. For the most part they are in remote, wild country where Joe set up to document.

There are commercial camera traps available, but these (for the most part) have fixed lenses and lower resolutions than DSLRs. Joe needed to use regular DSLRs. In addition to the animal shots, he felt it was necessary to record the background environment and show the habitat. For this, he employed Nikon 7100 cameras with 10–24mm zoom lenses, Trailmaster 1550 infrared motion-sensing triggers, and Nikon flash units—all in special-built weatherproof housings. Some of the camera housings were designed and built by the National Geographic Society. Other units used on Joe’s project utilized P&S still cameras and GoPro cameras.

Joe had a limited supply of these camera traps, so they had to be placed carefully. To do this, he worked closely with researchers and used their GPS data (gathered from radio-collared pronghorns) to predict the paths that the pronghorns might take. Then, each camera had to be situated to record not only the animal(s) but also their surrounding habitat. Usually, the cameras were set at or near ground level. It remains a chancy process, and a lot of luck is involved. “If I get one or two great shots a year, I feel good,” says Joe.

He did get great shots. Over time, he compiled a remarkable record of pronghorn movement and their terrain and habitat. Many of his photos have been featured in National Geographic and other important publications.

“Wait for me, Mom.” This young polar bear is jumping to join the mother in the waters off Svalbard, Norway. This photo, shot from the deck of a boat, is symbolic of the plight of polar bears today: warming climate is shrinking the arctic ice that polar bears need to successfully hunt seals from. With continued warming, this young polar bear may not survive to adulthood. (400mm, 1/4000 second) Photo credit: Odalys Muñoz Gonzalez.

This lioness drinking from a small stream is not aware of toxic elements that may have leached into the water from a uranium mine on the edge of the Selous Game Reserve in Tanzania. It may not be possible to photograph toxins directly, but using photos like this can point out how wildlife might be affected when they drink poisoned water.

Arctic and Antarctic. We’ve heard in recent years about the melting ice in the Arctic and Antarctic. In the Arctic region, the ice pack is crucial habitat for polar bears. Polar bears use arctic ice to hunt seals, a primary food source. With warming temperatures, the sea ice is melting earlier in the year and this forces the bears to shore before they have built sufficient fat reserves. They cannot hunt seals very well from shore. The top left photo, taken in Svalbard, Norway by my friend Odalys Muñoz Gonzalez, symbolizes so well the plight of polar bears in this warming climate.

Water Habitats. We tend to think of water supplies tainted by chemicals and other contaminants solely in terms of human health hazards, but wildlife is affected as well. Wildlife biologists are fearful of a uranium mine placed in and near the edge of the Selous Game Reserve in southern Tanzania. The Selous game reserve in Africa is so large that controlling elephant poaching has been a problem. The uranium mine can have a serious impact on the whole food chain because the radioactive and toxic waste products can leach into streams flowing into the reserve. Water is a vital component in any ecosystem.

In North America, water quality and pollution are serious issues. In Alaska, as in other places, there is a close link between healthy wildlife populations and water quality. Grizzly bears (also called coastal brown bears) are reliant on healthy salmon migrations, and certain proposed mining operations can produce toxic pollutants that have a serious impact on the salmon population in the stream systems.

Ethics in Wildlife Photography

Photographing animals in the wild can be frustrating and rewarding. In some of our national parks, species such as deer, elk, bison, and (in Alaska) even grizzly bears have become habituated to the presence of humans in their midst. That does not mean they are tame, however. They are still subject to stress from human pressure. When you are photographing wildlife, learn their body language—especially as it applies to reacting to your presence. It can be obvious, in most cases. If the animals appear to be stressed, back off. The welfare of the animal should be paramount.

Salmon migrating upstream in Kamishak Bay, AK. Photo made with Nikonos underwater camera, 35mm focal length.

Any institution that exploits animals solely for profit should not be utilized or supported. There are so-called game farms that keep animals in cages and release them for groups of well-paying photographers. Between shooting sessions, these animals are often kept in tightly confined cages—and, in some cases, under cruel conditions. The species include mountain lions (cougars), bears, bobcats, and even Siberian tigers! Don’t support these traffickers in animal mistreatment.

To recap, here are some key points to consider:

1. Don’t overlook the small critters.

2. Try to relate threats to the habitat with the inhabitants of the place.

3. Keep careful records of where, when, and what the animal is.

4. Include important information in the metadata of the image, including GPS coordinates.

5. Do research on the area you’re documenting. Are there rare or unusual mammals or birds? Threatened or endangered species? Where possible, relate the wildlife to its environment.

6. Contact and work with researchers. They can use your help—and vice versa.

Grizzly bears (coastal brown bears) are reliant on migratory salmon for a primary food source. The salmon, in turn, must have unpolluted waters for spawning. You can’t directly photograph pollution in the water, but you can show wildlife that is dependent on the fish in tho water.