12. Working with Organizations (Or Creating Your Own)

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed it’s the only thing that ever has.” —Margaret Mead

So far, I’ve covered some of the nuts and bolts of creating strong photographs. Now, let’s concentrate on the nuts and bolts of serious involvement in the conservation part. This has to do with working with conservation organizations or possibly creating your own organization.

The Sierra Club has 64 chapters throughout the country. The National Audubon Society has nearly 500 local chapters or affiliates in various regions and states. Becoming a member of one or more of these organizations can be a great aid in your conservation work. In fact, it would be well worth your time and expense to join and support as many of these organizations as you can.

Most have print and online publications that keep you apprised of current conservation issues. These publications can be a very effective way of displaying your work and alerting others to your conservation issues. More importantly, if you are involved in your own conservation battle, the members and staff of these organizations can provide vital advice and support. And finally, having the backing of a large, national organization for your fight gives you greater credibility. You can also benefit from the experience and expertise of their members. For example, members and staff of the Sierra Club can give you good legal insight, help draft protective legislation, and offer advice on getting representatives to introduce the bill.

The downside to having your battle associated with a large national organization is that there may not be a local chapter or affiliate near you to work with. Working with the national office of these organizations can be time consuming. As you can well imagine, the Sierra Club, Wilderness Society, and other big groups have a lot of large issues to deal with, and your own issue may not be of very high priority for their staff.

There are some advantages to organizing a separate organization for a specific battle. First and foremost is name recognition. The place you are working to preserve should be in the name. This can help attract local and regional attention. Having your own organization does not preclude working with the big, national conservation organizations—in fact, it helps to do so because it shows that your cause is attracting both local and regional concern. Plus, you get the benefit of the national organization’s expertise.

Hells Canyon Preservation Council. When fighting to stop the dam in Hells Canyon, we founded the Hells Canyon Preservation Council (HCPC). “We,” it turns out, were only eight people. Here’s how eight people stopped a project that was close to starting—and went on to get legislative protection through Congress.

In 1967, I was president of the Idaho Alpine Club. An invited speaker for our monthly programs gave a presentation on Hells Canyon, a little-known place on the border of Idaho and Oregon. Few of us knew at the time that it is the deepest gorge in America—almost 2000 feet deeper than the Grand Canyon. The program was a real eye opener. We discovered that this magnificent place was about to be destroyed by the proposed High Mountain Sheep dam, a dam nearly as large as that in Glen Canyon.

One of my first photos of Hells Canyon.

At this time, the Sierra Club was fighting to stop construction of two large dams in the Grand Canyon. That battle had caught the attention of the American public. Maybe we had a chance to save Hells Canyon if we could get the word out. But how?

A letter from radio and television star Arthur Godfrey accepting an invitation to visit Hells Canyon. On subsequent radio shows he gave glowing accounts of his visit, the awesome beauty of the canyon, and the need to save it. It brought national attention to the battle we were fighting to save this little-known place.

Graffiti left by the would-be dam builders. The initials stand for High Mountain Sheep (name of the proposed dam) and Pacific Northwest Power company.

Shortly after forming HCPC, we contacted the Sierra Club’s Pacific Northwest representative, Brock Evans. Brock, a recent law school graduate, jumped into our battle right away by filing an intervention on our behalf with the Federal Power Commission, which was set to rule on the power company’s license to build the dam. Our formal intervention was intended to build a strong case for not building it. We soon began conducting a number of “show me” trips to get members of the press involved. At first it was local and regional reporters; later, we were able to get a writer from the New York Times and from Life magazine.

At this time, one of the most popular television and radio entertainers was Arthur Godfrey. He had daily radio programs and a weekly television show. On a whim, I wrote a letter to Godfrey and invited him on one of our “show me” trips. I never expected a response, let alone an acceptance—but a month later, I received a letter from him saying he would be delighted to visit Hells Canyon. Godfrey’s account of the trip reached a large national audience, and he returned the following year with then Secretary of the Interior Wally Hickel. This trip also resulted in widespread publicity for our cause.

In the fall of 1969, I went to New York to visit the office of Audubon magazine, which was scheduled to publish my article and photo essay on Hells Canyon in their January 1970 issue. At that time, Audubon was an award-winning magazine noted for its quality writing and superb reproduction of photographs. I was thrilled with getting my work published there.

My visit coincided with the arrival of the page proofs from the printer for the January issue. I gathered several copies of the pages of my photos and hopped a plane to Washington, DC, where Brock Evans had arranged a visit to the office of the newly elected junior senator from Oregon, Bob Packwood. We sat in his office and I laid the pages of the article on his desk. He turned the pages slowly, studying all the photos. When he finished he looked up and said, “Holy smoke. Is this in my state?”

Boyd Norton rowing Pete Seeger on a 1972 raft trip in Hells Canyon. Seeger wrote a song about the canyon while there. Photo credit: Larry Williams.

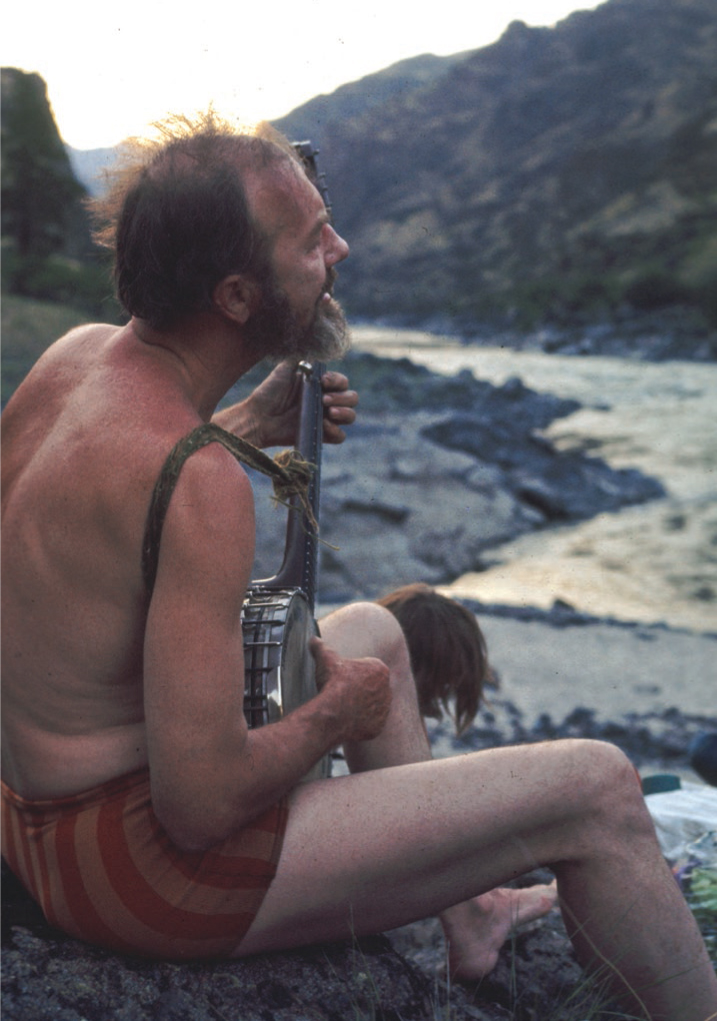

Pete Seeger serenading Hells Canyon at an evening’s camp along the Snake River.

Early-morning sunlight paints golden colors on the steep walls of Hells Canyon.

Packwood went on to introduce our bill to establish a Hells Canyon National Recreation Area and Wilderness. A few of us from the Hells Canyon Preservation Council attended the first Senate hearing on the bill. Arthur Godfrey also testified, which drew a large number of television and press reporters to cover it. The publicity for our battle was growing and Hells Canyon was transformed from a place no one knew into one that was now recognized as one of America’s scenic wonders. However, it took four more years of hearings and deliberations before our bill was passed.

In 1972, I took Pete Seeger on a six-day whitewater raft trip there, and this furthered publicity for saving the canyon and river. In 1974, the CBS News team joined us on another raft trip, this time with Senator Bob Packwood. Finally, on December 31, 1975, the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area bill was passed by Congress and signed into law. The dam was halted and Hells Canyon was saved. It took eight years from the time we started the fight, but it was worth it.

Not every threatened place is famous. But that should not deter you from using every means possible to save your favorite piece of wild land. Do not underestimate the power of your own photography in showing the world the wonders and value of threatened wild lands.

Elk in Maxwell Wildlife Refuge near McPherson, KS. Though small, this reserve offers protection for native species. Local professional photographer Jim Griggs donates his time and photographs to promote the refuge. Income from visitors helps maintain it. Photo credit: Jim Griggs.

Photographer Jim Griggs conducts photo workshops at the Maxwell Wildlife Refuge, providing income that helps maintain this reserve. Photo credit: Jim Griggs.

A small herd of bison is maintained on the refuge. Photo credit: Jim Griggs.

A good example of a little-known place being saved and maintained by photography is the Maxwell Wildlife Refuge near McPherson, KS. Never heard of Maxwell? It’s not as famous as Yellowstone or Serengeti, but this small refuge (2800 acres) is important for protecting a part of some native prairie lands and the wildlife it supports. Descendants of an early settler, Henry Gault Maxwell, deeded this land to the Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks, which created the refuge.

Professional photographer Jim Griggs, who lives nearby, has made it a personal project to maintain Maxwell Refuge and promote its values to the public. He donates his photos to the refuge in order to promote it. In addition, Jim conducts photo workshops here, and the fees from those classes help to maintain the refuge. His role points to a need for many areas that have some degree of protection—but without funding, the land and the wildlife might be degraded over time.

You have to get involved; taking pretty pictures is not enough. Organize to fight a particular battle. Join a conservation organization fighting a battle—or form your own local group. Donate the use of your photographs to groups who can’t afford to pay. Most often, conservation issues involve hearings, some on the local level, some regional, some national. Your photos make you an expert. Testify at these hearings and use your photos to show what should be saved and why. You can make a difference.