“Photography is a small voice, at best, but sometimes one photograph, or a group of them, can lure our sense of awareness.” —W. Eugene Smith

What next? After the pictures are taken and processed, you need to get them out there so people can see and react. Not everyone feels as you do about protecting nature, but they may be amenable to your message if it is presented well and properly. Let’s look at some ways to reach an audience.

In the previous chapter, I discussed the benefits of working with existing conservation organizations. Many of these have publications, both in print and online, that are an excellent way for showcasing your work and getting your message across. If you’ve been working with representatives of an organization, use these contacts to gain access to the publications.

When submitting digital work, find out the publications’ preferred file formats. Usually, a high-resolution (300dpi) JPEG is needed for print publications. For online use, a lower resolution (72dpi) is the norm. The preferred pixel dimensions may vary, but usually 2000 to 3000 pixels in the longer dimension works for print; smaller files will be needed for online use.

When submitting to a publication, more is not necessarily better. Most editors prefer a tight edit, so don’t submit a lot of similar pictures of the same scene or subject. Obviously, it should be your best-quality work. It’s tough to edit your own work, but it can help to keep the story in mind. Do the pictures reinforce the story of what the place is all about and what the threats are to it? Try to picture yourself as a reader or viewer trying to understand what it’s all about.

Print exhibitions are another good way to share your work—though fewer people might see it and react to your message. A good exhibit can also be expensive to produce and promote. Consider the time involved in making the prints (if you do it yourself) or the expense of having the prints done by a lab. Matting, framing, and hanging the exhibit is an added expense.

On the plus side, you may sell some prints to defray some of your expenses in shooting and creating the exhibit. The sale of prints can be a good way to raise funds for your organization or a national conservation organization.

This exhibition featured photographs of the International League of Conservation Photographers (iLCP) and was sponsored by Fine Print Imaging and displayed at The Collective, a gallery in Fort Collins, CO. The people who frequent such exhibitions tend to be influential and may be of help to your cause.

If you go the exhibition route, I recommend working with local businesses or organizations for sponsorship. If you are a good salesperson, you may convince one of these entities to put up the money for an exhibition by pointing out the good, positive publicity from such sponsorship. It has happened in the past and it continues to be one way of attracting attention to a conservation issue.

Presentations can reach a large number of people over time. Many civic and social organizations are in need of programs for their members—as are camera or photography clubs. Contact them and make yourself available. PowerPoint and other programs make it easy to create effective digital slide presentations. You don’t need to be a great public speaker, but with practice you can become good at it. Here are a few tips.

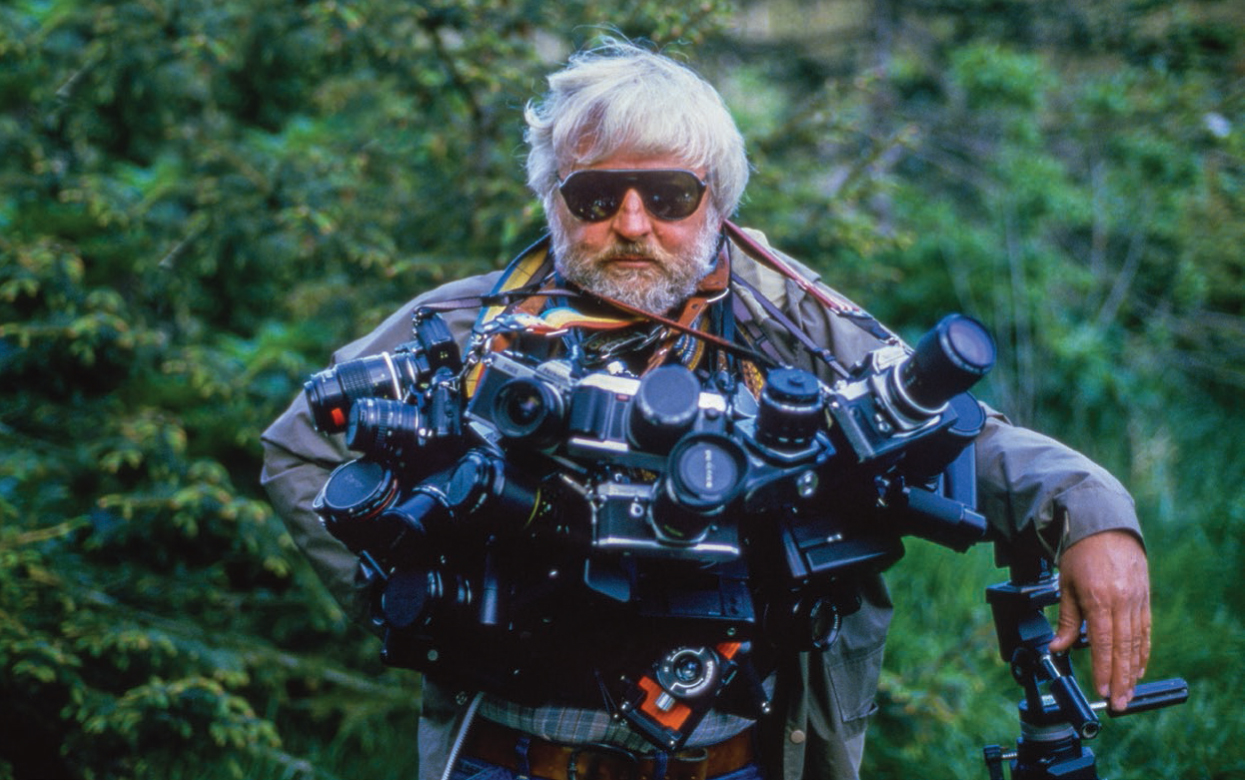

This shot of me with a neck full of borrowed cameras always elicits some laughter. Poking fun at myself helps make audiences receptive to my message.

Keep It Simple. True, the issue you are dealing with may have a lot of complexities, but it’s often not necessary to go into tremendous detail. Hit the high points and use your best images to drive home the beauty of the place you want to save.

Show the Location. Use maps as well as photos. If the place is little known, it’s best to let the audience know where it is—and perhaps even encourage them to visit it. Google Earth is a useful tool for showing the locale. It’s easy to create a slide from a screen capture.

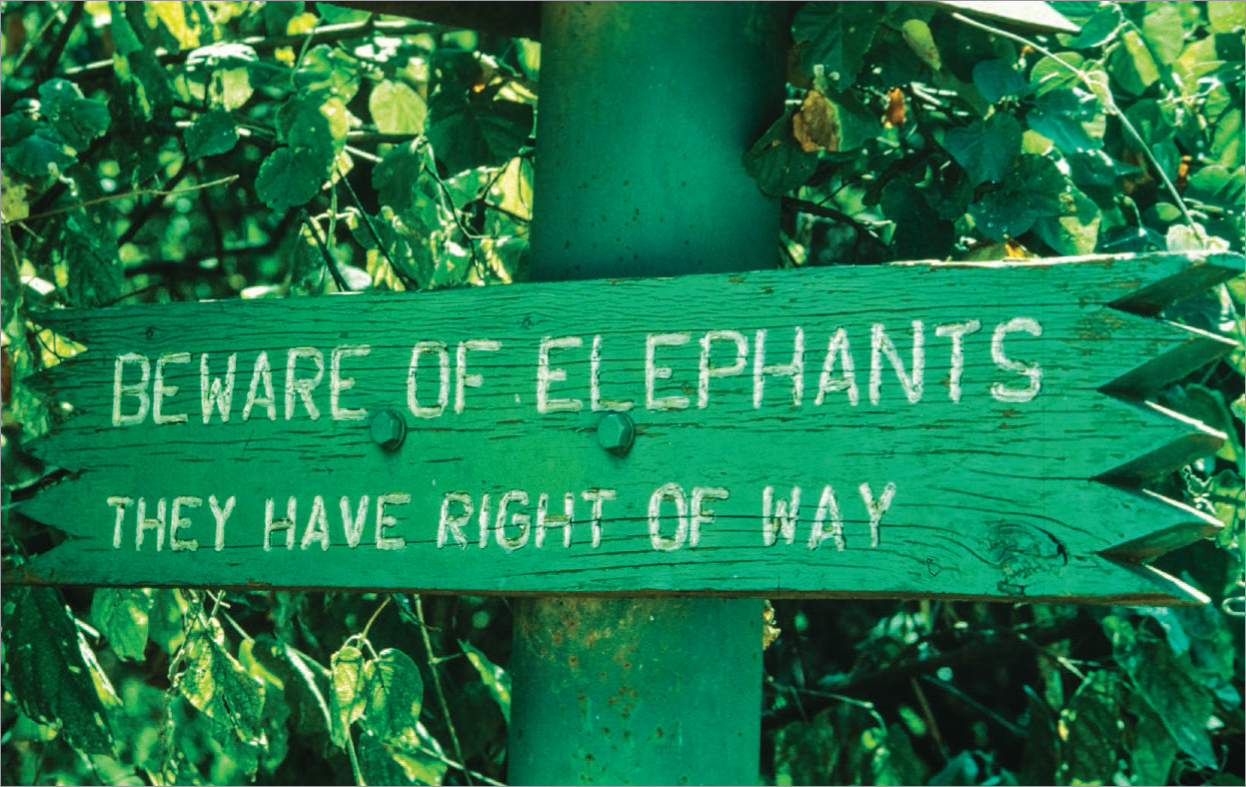

Depending upon how much time I have for my program, I sometimes start with a series of about a dozen silly signs I have photographed over the years. It not only warms up the audience, but it conveys a message that you are not embarking on a dreary presentation.

Don’t Rely on the Internet. Don’t rely on using the Internet for parts of your presentation. First of all, you can never be sure of good Internet connectivity where you’ll be presenting. Moreover, if you have to stop your presentation in order to connect and find the material you want to show from a website, it will really slow down your show.

Use Humor. Over many years of doing presentations, some at big international gatherings, I’ve learned that small doses of humor help keep your audience with you. As an audience warm-up I sometimes poke fun at myself and my profession, using a silly photo I made years ago with some borrowed cameras (top left). I’m always on the lookout for additional humorous photos, and I have a file of silly signs I use to warm up audiences. Two audience favorites are shown below.

Keep Your Cool. In presentations on conservation issues, there is always a danger of becoming too strident and losing the support of your audience. Saving wild places is an emotional issue but it’s best not to let your passion over the issue turn off an audience. I find it to be effective if I maintain a low-key tone to my presentations and let my photographs carry the message.

Add Video Clips. In addition to still photos in presentations, I use an occasional video clip to liven up the presentation. Be careful that you don’t make the videos too long; use them for short interludes between slides—no longer than 10 to 12 seconds, unless the subject matter is really compelling.

Finesse Your Timing. Giving effective presentations is an art form and you should practice making your programs entertaining and informative. You also need to be flexible in timing your program. Some events have strict rules on the length of presentations, so you need to be able to add or subtract material to adhere to those rules. Even when there is some flexibility in the program length, keep in mind that more is not necessarily better. Unless you are an experienced entertainer, it is hard to keep an audience interested when your program exceeds 30 or 40 minutes in length. In addition, I always plan my programs to allow time for questions and audience interaction afterward. This Q&A period helps to engage the audience—and often you will find strong supporters of your cause.

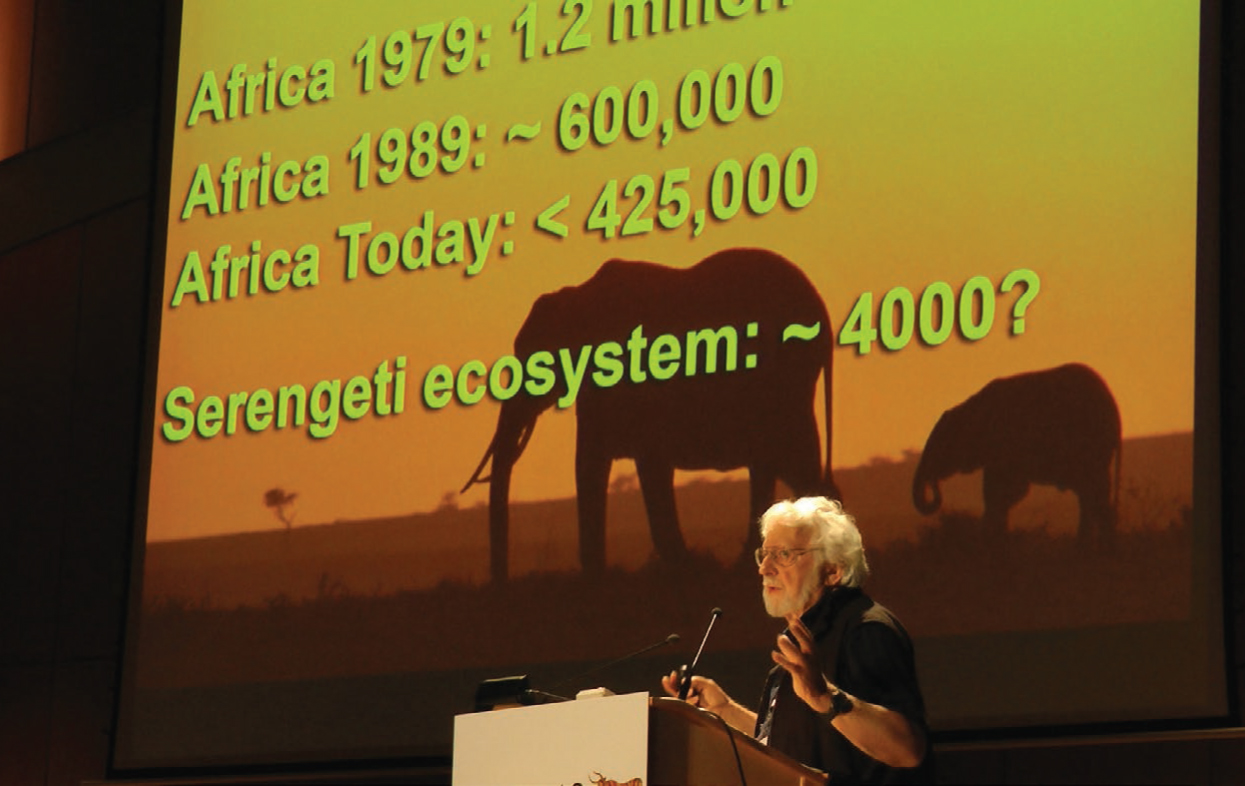

Short programs can be a real challenge. At the 10th World Wilderness Congress in Spain in 2013, the plenary presentations were limited to 15 minutes. I was invited to speak on our battle to save the Serengeti ecosystem and I had to make sure my presentation contained the most important information and could be presented in the allotted time without rushing. My photos were chosen carefully and I got double duty out of some by overlaying important wildlife population information.

Refine Your Visual Aids. Avoid using PowerPoint text slides that are loaded with bulleted stats and hard-to-read information. I can’t think of a better way of losing your audience. If you feel it is necessary to show some facts and figures to help people retain the information, get creative. Use some of your best photos with overlays but keep the information on the overlay to a minimum. One of my most effective statistical slides uses a favorite African lion photo—several lionesses and cubs lined up drinking from a waterhole. The first slide (usually on screen for a few seconds or so) has no information, just the lions drinking. The second has the shocking information about how rapidly Africa is losing its lions. It always elicits a reaction from viewers.

Vary Your Pacing. If you show every slide for exactly 12 seconds or explain a picture for minutes at a time, you will begin to hear the audience snoring. Your presentation is a symphony and you are the conductor. You may begin quietly and slowly build to a climax in the presentation. Some slides may warrant absorption and appreciation for their beauty. Some may be fast paced—a sequence of action shots, for example. Scenes of destruction may be shown at a faster pace than scenes of quiet beauty. Vary your presentation and speech to pull your audience in, both visually and audibly.

I find it effective to overlay some of my photos with statistics rather than using plain PowerPoint backgrounds.

Keep your information slides simple—don’t cram in too much text or they will be hard to read.

Tailor Your Program to Fit the Audience. Obviously, you would not give the same presentation to an older audience as you would to grade-school kids. When I give programs to conservation organizations, I’m careful not to tell them things they already know about an issue. For general audiences, I assume that they are there to learn something from me about this particular issue—but I also recognize that not everyone shares the same passion for my conservation project. So I try to make my program entertaining enough to generate some passion and interest on their part.

In the days of slide projectors, making changes involved a time-consuming process of unloading the slides, adding or rearranging them on a lightbox, then putting them back in the tray in the proper order (and hoping that they weren’t backwards or upside down). Today, it’s all done on a computer screen and it is easy to rearrange or add new material. So keep your program active and lively and tailor it to fit the audience.

Practice, Practice, Practice. Know what you are going to say and how you will say it. Reading from notes is boring, so avoid that if possible. Every program I give is done extemporaneously, with no notes whatsoever. I never know exactly what I am going to say, but I know my topics well enough to keep the programs flowing smoothly.

Giving presentations is time consuming, but the personal interaction with people in the audience has often led to strong new supporters for the cause—and, sometimes, engaging people who have expertise in fields where I had none.

In my earliest conservation battles, there was no Internet. It took a great deal of time to make news contacts via snail-mail, and it took even more time to get articles and photo essays published. Months, even years, were spent garnering support and lobbying for legislation. In retrospect, it seems miraculous that we could win some of those battles because of the slow pace.

Today, when time seems to be crucial in stopping threats to wild areas, social media is one way of eliciting rapid response and perhaps action. A case in point is our recent battle to save the Serengeti ecosystem from a proposed and destructive commercial highway.

In May of 2010, I was in the Loliondo Game Controlled Area (adjacent to Serengeti National Park) and learned of plans for a large, paved highway that would slice east to west across Serengeti National Park and adjacent areas. It was planned to accommodate hundreds of big trucks every day—and it lay in the path of the largest land mammal migration on earth. This could severely impact one of the world’s last, large protected ecosystems—already classified as both a national park and a World Heritage Site. It had to be stopped.

On returning home, I contacted a few activist friends who had also traveled frequently to Serengeti and together we created a Facebook page: STOP THE SERENGETI HIGHWAY. Almost immediately, it began to attract attention—and within days we had hundreds of followers on that page. A few months later, that number grew to thousands (as of this writing, it is approaching 70,000). So how did this help?

First of all, this news of the highway was so upsetting to everyone that we began receiving private correspondence with information and contacts for key news media people. Using these contacts, we began feeding information about the highway plans and its impact. This led to major news stories in The New York Times, the Guardian (London), and other news outlets with widespread readership. These, in turn, incited a large public outcry aimed at the Tanzanian government.

In December of 2010, Richard Engel, Chief Foreign Correspondent for NBC News, visited the affected area, traveling the proposed route across Serengeti. Later, he gave major reports on NBC Nightly News, the Today Show, and MSNBC. More outcry followed.

Also in 2010, we formed the non-profit, tax deductible organization Serengeti Watch as part of Earth Island Institute (a major conservation organization founded by my old mentor and friend David Brower). This allowed us to raise funds and carry out conservation education programs in Tanzania, with the intent of building strong grassroots support for saving not only Serengeti but other Tanzania reserves and parks. These programs have been very successful and conservation support is growing.

Have we managed to stop the proposed Serengeti highway? Not yet, but the Tanzanian government seems to have slowed the efforts to get it funded. Moreover, Serengeti Watch partnered with the Frankfurt Zoological Society to propose an alternative route that would completely bypass the Serengeti ecosystem to the south of the park. Currently, the German government and the World Bank have given the Tanzanian government the funding needed to carry out a study of this southern route. So, I am cautiously optimistic that the destructive highway will not be built. And we continue our efforts at conducting conservation education programs for students and teachers in Tanzania.

Using social media, websites, and blogs is effective. A good blog or website can be a great showcase for your photographs and video (and links to it can be used as posts to your social media sites). Programs like Wordpress feature image gallery templates that make it easy to build a good website and display the beauty of what you hope to save. Don’t forget to make it clear how viewers can help and become involved—even if it’s just by signing a petition.

There are a great many online magazines devoted to environmental subjects. A Google search for “online environmental magazines” yields dozens of listings. Some are newsletters and some are online versions of such print magazines as Audubon. Before making a submission, check their website for guidelines (often, that information is buried deeply on the website to avoid a deluge of submissions). Nearly all publishers will request that you query before submitting anything. You’ll need to be patient because the whole process of querying and submitting can take a lot of time.

Your chances of getting your photo story published are greatly enhanced if you develop some writing skills. Even providing extensive caption information for your pictures can enhance your publishing chances. It doesn’t have to be flowery prose—in fact, it’s better that it’s not—but you should be able to tell your conservation story succinctly, compellingly, and accurately.

I think every nature photographer aspires to have a coffee table book published with his or her best photos. In today’s market, however, that’s not likely to happen through conventional publishing houses unless you have a story with widespread appeal and lots of outstanding pictures—plus a publishing track record. That leaves most people with the self-publishing option, which is now easy and may be a good route for getting your message out there. However, don’t expect this to bring in much monetary reward. A well-done photo book (say 8×10 inches, soft cover, with 20 pages of photos and text) can be printed by companies like Blurb or My Publisher for about $20 per copy. In larger quantities, the price per copy drops by a few dollars. (You can, of course, create more pages or do a larger sized book, but the cost goes up accordingly.)

There are two major benefits of self-publishing a book on your cause. One is to use it as a fund-raiser for conservation efforts. The other is to use the book as a give-away to decision makers—legislators, representatives, senators, etc. A nicely designed book can covey a lot about the habitat and wildlife of a place you are working to save. As I suggested in my section on print exhibitions, you may be able to find a local or regional business to underwrite the cost of publication. This could also be valuable to the business if you offer to include a page giving credit to them—perhaps with a photo or two promoting them.

One advantage to starting your own organization, with a name that includes the place you want to preserve, is that your news releases will attract more attention than if you simply sent them out under your own name.

Creating news releases is an art form. Shorter is better; two- and three-page releases don’t get read. If you are not comfortable writing it yourself, get some help from someone who is good at writing clearly. Also, don’t send out news releases unless there’s something newsworthy—an upcoming or just-completed hearing, an item about some new species discovered in the place you want to preserve, or perhaps some new photos of a little-known creature in residence there.

If you have just started your organization, that is newsworthy in itself—especially if you have gotten the support of a large group of people who also want to save your place. It is rare that a media outlet will run just a news release, so be sure to include your contact information in the heading of the release. If you do attract attention, be prepared for an interview by a news reporter or maybe a local television station. All of this is worth the effort because it can gain more widespread support for your cause.